CHAPTER 3

Ceremonial Banquets

“What did you eat?” would probably be the first question we would ask someone returning from a fancy meal. But in late medieval and early modern Japan a more appropriate question to ask would have been: “What could you eat?”—especially if the banquet was at the imperial court or for a high-ranking samurai like the shogun or a powerful daimyo. This question recognizes the odd fact that avoiding eating was often the most polite thing to do at a formal banquet. On some occasions, manners compelled guests to delay touching certain dishes until important moments in the banquet, and to not eat them at all until they had admired them in a prescribed way. In other instances the polite thing to do was to pretend to eat something, surreptitiously pocketing a morsel of food instead of consuming it. Some dishes served at banquets were meant to be taken home rather than eaten immediately. Certain snacks were served in a form that could not be consumed at all. In extreme instances, a guest might sit down to an elaborate and visually stunning banquet in which only a small number of dishes could be eaten. To know what to do in these circumstances, diners had to rely on past custom, visual cues, and a familiarity with the symbolic associations of ingredients and of the meanings of certain place settings, and remain attentive to any hints from their host about what they were expected to eat and what they should not try to consume.

The question “What could you eat?” also has direct bearing on the main theme of this book: cuisine in premodern Japan can be defined as a fantasy with food, a process that fashioned artistic and intellectual content from food production and consumption, so that people saw beauty and meaning in food rather than viewing it as simply something to put in their mouths. The knife ceremonies (shikib ch

ch ), discussed in the previous chapter, enabled “men of the carving knife” (h

), discussed in the previous chapter, enabled “men of the carving knife” (h ch

ch nin) to showcase their occupational skills at banquets in brilliant displays of carving fish and fowl as both an entertainment and a religious ritual, but the primary duty of these chefs was the creation of elaborate banquets for daimyo, shoguns, aristocrats, and the emperor.

nin) to showcase their occupational skills at banquets in brilliant displays of carving fish and fowl as both an entertainment and a religious ritual, but the primary duty of these chefs was the creation of elaborate banquets for daimyo, shoguns, aristocrats, and the emperor.

The most formal of these banquets was the shikish ry

ry ri, which we could translate as “ceremonial cuisine” or “ceremonial style of cooking,” recalling the ambiguities of the term ry

ri, which we could translate as “ceremonial cuisine” or “ceremonial style of cooking,” recalling the ambiguities of the term ry ri for premodern Japan, as described in chapter 1. Not a term precisely defined in the period—or by scholars today—ceremonial cuisine was synonymous with practices of not eating that demanded the appreciation of food in other ways, sometimes as a symbol evoking transcendent values such as martial virtues or marital felicity, and other times as an art form akin to flower arrangement or sculpture. The persons chiefly responsible for creating the guidelines for viewing food in these ways—that is, for creating this culinary code, to borrow Priscilla Parkhurst Ferguson’s turn of speech—were the same people who made these dishes, the h

ri for premodern Japan, as described in chapter 1. Not a term precisely defined in the period—or by scholars today—ceremonial cuisine was synonymous with practices of not eating that demanded the appreciation of food in other ways, sometimes as a symbol evoking transcendent values such as martial virtues or marital felicity, and other times as an art form akin to flower arrangement or sculpture. The persons chiefly responsible for creating the guidelines for viewing food in these ways—that is, for creating this culinary code, to borrow Priscilla Parkhurst Ferguson’s turn of speech—were the same people who made these dishes, the h ch

ch nin. They wrote about these matters in their occupational writings called culinary texts (ry

nin. They wrote about these matters in their occupational writings called culinary texts (ry risho). Because these texts provide the main source of information for this discussion, it is important to understand their characteristics before examining what they reveal about not eating as a means to designate the thought-provoking and artistic aspects of food.

risho). Because these texts provide the main source of information for this discussion, it is important to understand their characteristics before examining what they reveal about not eating as a means to designate the thought-provoking and artistic aspects of food.

CULINARY TEXTS: THE WRITINGS OF H CH

CH NIN

NIN

The early and detailed culinary writings (ry risho) of h

risho) of h ch

ch nin include not only information about knife ceremonies (shikib

nin include not only information about knife ceremonies (shikib ch

ch ) but also recipes, descriptions of model banquets, information about table manners, and most important for this chapter, details about the significant role of inedible dishes in banquets as markers of artistry and metaphor. From the late fifteenth century through the mid-seventeenth century, before the advent of published culinary books (ry

) but also recipes, descriptions of model banquets, information about table manners, and most important for this chapter, details about the significant role of inedible dishes in banquets as markers of artistry and metaphor. From the late fifteenth century through the mid-seventeenth century, before the advent of published culinary books (ry ribon), these texts were the dominant writings about cuisine.1 In contrast to the ry

ribon), these texts were the dominant writings about cuisine.1 In contrast to the ry ribon, which were printed works for a popular audience, culinary texts were created by and for a select readership of specialists to facilitate creation of the most refined dining experiences for the elite. Even after the advent of published works, culinary texts remained authoritative because they described an elite style of dining that lasted until the end of the Edo period.

ribon, which were printed works for a popular audience, culinary texts were created by and for a select readership of specialists to facilitate creation of the most refined dining experiences for the elite. Even after the advent of published works, culinary texts remained authoritative because they described an elite style of dining that lasted until the end of the Edo period.

Table 2 presents a list of the earliest culinary texts.2 As we can see from the titles, most of these culinary texts, beginning with Shij School Text on Food Preparation, are associated with a specific h

School Text on Food Preparation, are associated with a specific h ch

ch nin lineage, a hereditary line of chefs like the Shij

nin lineage, a hereditary line of chefs like the Shij and the

and the  kusa, who espoused distinct styles of cooking.3 The creation of these culinary texts marked the consolidation of these h

kusa, who espoused distinct styles of cooking.3 The creation of these culinary texts marked the consolidation of these h ch

ch nin lineages and their artistic styles in the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries.4 However, practitioners claimed a much older historical legacy for their lineages dating back to as early as the ninth century.

nin lineages and their artistic styles in the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries.4 However, practitioners claimed a much older historical legacy for their lineages dating back to as early as the ninth century.

Though distinct in their subject matter, culinary texts were representative of wider trends in arts and manuscript culture that prized “secret” writings associated with established lineages of occupational specialists. Writing, possessing, and selectively disseminating specialized texts were prominent ways to demonstrate authority in medieval and early modern Japan.5 Accordingly, “secret writings” (hidensho), texts discretely transmitted from master to disciple, were ubiquitous during these periods. They covered subjects ranging from carpentry to garden design to the martial arts to swimming to the tea ceremony. Especially valued were texts that demonstrated connections with prominent families. These followed a widely used strategy that equated membership either by blood or by apprenticeship in a prominent lineage as indispensable to any claim to authority in a given subject, from poetry to Noh theater to religious practice.

When we move beyond these broad generalizations, it is, unfortunately, difficult to connect the aforementioned culinary texts to specific authors and readers. Colophons in manuscripts usually provide the date and author, and sometimes the intended reader, but these offer little help in contextualizing the culinary texts. Seven of the ten texts listed in the table do not provide the name of the author, although a few bear the names of copyists who might be the actual authors. For example, Culinary Text of the Yamanouchi House (Yamanouchi ry risho) contains the statement that it is a transcription of “oral instructions of Yamanouchi Saburo Saemon (n.d.) of the Headquarters of the Middle Palace Guards (hy

risho) contains the statement that it is a transcription of “oral instructions of Yamanouchi Saburo Saemon (n.d.) of the Headquarters of the Middle Palace Guards (hy efu).”6 The Yamanouchi house became a prominent warrior house in Kyushu in the sixteenth century, but there is no evidence to suggest that someone in this lineage produced this text. Not much more is known about the people mentioned as authors of the other writings. Shij

efu).”6 The Yamanouchi house became a prominent warrior house in Kyushu in the sixteenth century, but there is no evidence to suggest that someone in this lineage produced this text. Not much more is known about the people mentioned as authors of the other writings. Shij Takashige (n.d.), named as author of Ancient Traditions of Flavorings for Warrior Households (Buke ch

Takashige (n.d.), named as author of Ancient Traditions of Flavorings for Warrior Households (Buke ch mi kojitsu), might be an early master of the Shij

mi kojitsu), might be an early master of the Shij lineage, but he is otherwise unknown. Likewise,

lineage, but he is otherwise unknown. Likewise,  kusa Kinmochi (n.d.), mentioned as author of Record of Three Formal Rounds of Drinking and 7-5-3 Trays (Shikisankon shichigosan zenbuki), could have been from the

kusa Kinmochi (n.d.), mentioned as author of Record of Three Formal Rounds of Drinking and 7-5-3 Trays (Shikisankon shichigosan zenbuki), could have been from the  kusa family of h

kusa family of h ch

ch nin in the employ of the Ashikaga shoguns. Ise Sadayori, specialist in warrior ritual, indicates in his text on bakufu customs and rituals, S

nin in the employ of the Ashikaga shoguns. Ise Sadayori, specialist in warrior ritual, indicates in his text on bakufu customs and rituals, S g

g

z

z shi (ca. 1529), that the Ashikaga shoguns employed chefs from both the Shinji and

shi (ca. 1529), that the Ashikaga shoguns employed chefs from both the Shinji and  kusa schools.7 Chefs from the

kusa schools.7 Chefs from the  kusa school later served the Shimazu daimyo house in Kyushu from 1615 to 1855.8 However, in the absence of other evidence about

kusa school later served the Shimazu daimyo house in Kyushu from 1615 to 1855.8 However, in the absence of other evidence about  kusa Kinmochi and the rest of the people named as authors, their identities remain the object of speculation. For that reason, modern scholarship on these texts considers these works to be anonymous and has focused on their contents, not their authorship.9

kusa Kinmochi and the rest of the people named as authors, their identities remain the object of speculation. For that reason, modern scholarship on these texts considers these works to be anonymous and has focused on their contents, not their authorship.9

TABLE 2 EARLY H CH

CH NIN CULINARY TEXTS (RY

NIN CULINARY TEXTS (RY RISHO)

RISHO)

Title |

Author |

Date of

Compilation |

Shij School Text on Food Preparation (Shij School Text on Food Preparation (Shij ry ry h h ch ch sho) sho) |

Unknown |

1489 |

Culinary Text of the Yamanouchi House (Yamanouchi ry risho) risho) |

Unknown |

1497 |

Ancient Traditions of Flavorings for Warrior Households (Buke ch mi kojitsu) mi kojitsu) |

Shij Takashige Takashige |

1535 |

Transcript of Lord  kusa’s Oral Instructions ( kusa’s Oral Instructions ( kusadono yori s kusadono yori s den no kikigaki) den no kikigaki) |

Unknown |

c. 1535–73 |

Transcript of the Knife (H ch ch kikigaki) kikigaki) |

Unknown |

c. 1540–1610 |

Culinary Text (Ry ri no sho) ri no sho) |

Unknown |

1573 |

Culinary Text of the  kusa House ( kusa House ( kusake ry kusake ry risho) risho) |

Unknown |

c. 1573–1643 |

Record of Three Formal Rounds of Drinking and 7-5-3 Trays (Shikisankon shichigosan zenbuki) |

kusa Kinmochi kusa Kinmochi |

1606 |

Shij -House Decorations for 7-5-3 Trays (Shij -House Decorations for 7-5-3 Trays (Shij ke shichigosan no kazarikata) ke shichigosan no kazarikata) |

Unknown |

1612 |

Secret Writings on Culinary Slicing (Ry ri kirikata hidensh ri kirikata hidensh ) ) |

Takahashi Gozaemon et al. |

Before 1659 |

Secret Writings on Culinary Slicing (Ry ri kirikata hidensh

ri kirikata hidensh , hereafter Secret Writings), published before 1659, provides the most detailed information about authorship and readership, but it also raises the most questions. Secret Writings is a compilation of eight different culinary texts.10 After each of its volumes, it bears a colophon stating that it was a transmission of writings of the Shij

, hereafter Secret Writings), published before 1659, provides the most detailed information about authorship and readership, but it also raises the most questions. Secret Writings is a compilation of eight different culinary texts.10 After each of its volumes, it bears a colophon stating that it was a transmission of writings of the Shij school from Takahashi Gozaemon to Nakamura J

school from Takahashi Gozaemon to Nakamura J saemon (n.d) in 1642.11 According to the culinary historians Kawakami K

saemon (n.d) in 1642.11 According to the culinary historians Kawakami K z

z and colleagues, both of these men were chefs in the employ of the Tokugawa shoguns.12 In the colophon, several additional authorities are listed before Takahashi’s name, as people in the “Shij

and colleagues, both of these men were chefs in the employ of the Tokugawa shoguns.12 In the colophon, several additional authorities are listed before Takahashi’s name, as people in the “Shij lineage who have transmitted and received this” (Shij

lineage who have transmitted and received this” (Shij ke denju). They are Sonobe Shinby

ke denju). They are Sonobe Shinby e, Yoshida Go’uemon, Sonobe Izumi no Kami, Haneda Kamiuemon, and Takahashi Konby

e, Yoshida Go’uemon, Sonobe Izumi no Kami, Haneda Kamiuemon, and Takahashi Konby e.13 However, no conclusive evidence associates these individuals with Secret Writings, or indicates that they actually existed. Although these may have been real people who authored or once held these writings, the use of their names in this way suggests that Takahashi Gozaemon or someone else simply added these five names as a way to grant cohesion and authority to the work, a practice seen in other published collections of “secret” writings in this period.14 Significantly, the earliest extant version of Secret Writings lacked a shared title for its nine volumes.15 In other words, the consistent use of the same names of culinary authorities provided evidence to readers that the texts were related. While the individuals listed were not themselves famous—we know this by the lack of other mention of them in period sources—their family names were recognizable as h

e.13 However, no conclusive evidence associates these individuals with Secret Writings, or indicates that they actually existed. Although these may have been real people who authored or once held these writings, the use of their names in this way suggests that Takahashi Gozaemon or someone else simply added these five names as a way to grant cohesion and authority to the work, a practice seen in other published collections of “secret” writings in this period.14 Significantly, the earliest extant version of Secret Writings lacked a shared title for its nine volumes.15 In other words, the consistent use of the same names of culinary authorities provided evidence to readers that the texts were related. While the individuals listed were not themselves famous—we know this by the lack of other mention of them in period sources—their family names were recognizable as h ch

ch nin who served the Tokugawa bakufu. Thus if the names were simply concocted and added to the text by someone as a way to lend greater legitimacy and coherence to the writings, that person could not have created a more authoritative provenance for a work on cooking.

nin who served the Tokugawa bakufu. Thus if the names were simply concocted and added to the text by someone as a way to lend greater legitimacy and coherence to the writings, that person could not have created a more authoritative provenance for a work on cooking.

Adding a title with the words Secret Writings (hidensh ) gave the work further prestige and lent it irony, since, besides being the only text in table 2 with the word secret in the title, it was also the only one to appear in print in the Edo period. The publishing trade in the seventeenth century saw the market value of “secret writings”; many older treatises in fields such as Noh theater, tea ceremony, and flower arrangement that had once been circulated in manuscript form were being revealed and published. Other “secret writings” were simply being cut out of whole cloth for this new readership, such as a text on the tea ceremony, Nanp

) gave the work further prestige and lent it irony, since, besides being the only text in table 2 with the word secret in the title, it was also the only one to appear in print in the Edo period. The publishing trade in the seventeenth century saw the market value of “secret writings”; many older treatises in fields such as Noh theater, tea ceremony, and flower arrangement that had once been circulated in manuscript form were being revealed and published. Other “secret writings” were simply being cut out of whole cloth for this new readership, such as a text on the tea ceremony, Nanp ’s Record (Nanp

’s Record (Nanp roku). This work, composed of teachings attributed to a disciple of tea master Sen no Riky

roku). This work, composed of teachings attributed to a disciple of tea master Sen no Riky , was actually concocted by Tachibana Jitsuzan (d. 1708), who hoped to use the text to jump-start a new school of tea. Earlier culinary texts written by h

, was actually concocted by Tachibana Jitsuzan (d. 1708), who hoped to use the text to jump-start a new school of tea. Earlier culinary texts written by h ch

ch nin before Secret Writings may not have been labeled as secret, but they were secret in practice by virtue of the fact that they were created for a restricted audience of initiates. They also remained secret because they were not widely disseminated until after the Edo period.16

nin before Secret Writings may not have been labeled as secret, but they were secret in practice by virtue of the fact that they were created for a restricted audience of initiates. They also remained secret because they were not widely disseminated until after the Edo period.16

The attempt to make Secret Writings appeal to a wider readership by adding the names of authorities and by using the word secret in the title indicates the work’s transitional nature. On the one hand, the information in Secret Writings stemmed from the older traditions of h ch

ch nin. For example, the first volume, Secrets of the Knife (H

nin. For example, the first volume, Secrets of the Knife (H ch

ch himitsu), provides information about preparing foods for courtly celebrations, along with detailed descriptions of cutting ceremonies (shikib

himitsu), provides information about preparing foods for courtly celebrations, along with detailed descriptions of cutting ceremonies (shikib ch

ch ) that were the h

) that were the h ch

ch nin’s trademarks. Three of the other texts in this compilation consist of diagrams of different designs for slicing fish and fowl in the knife ceremonies. The general tone of the volumes is specialized, and the contents difficult to decipher. On the other hand, as a published text that saw at least three print runs in the latter half of the 1600s, Secret Writings was available to an audience that encompassed not only professional h

nin’s trademarks. Three of the other texts in this compilation consist of diagrams of different designs for slicing fish and fowl in the knife ceremonies. The general tone of the volumes is specialized, and the contents difficult to decipher. On the other hand, as a published text that saw at least three print runs in the latter half of the 1600s, Secret Writings was available to an audience that encompassed not only professional h ch

ch nin but also aristocrats, upper-level warriors, and wealthy townsmen—in other words, anyone who could afford the cost of a technical work priced as much as several weeks of meals.17 Secret Writings was also contemporaneous with Tales of Cookery (Ry

nin but also aristocrats, upper-level warriors, and wealthy townsmen—in other words, anyone who could afford the cost of a technical work priced as much as several weeks of meals.17 Secret Writings was also contemporaneous with Tales of Cookery (Ry ri monogatari), published in 1643, the first culinary book written for an audience other than h

ri monogatari), published in 1643, the first culinary book written for an audience other than h ch

ch nin.18 Despite the fact that the former was for specialists and the latter was for a wider readership, both works share a feature common to published culinary books in that they have tables of contents, an innovation not found in earlier h

nin.18 Despite the fact that the former was for specialists and the latter was for a wider readership, both works share a feature common to published culinary books in that they have tables of contents, an innovation not found in earlier h ch

ch nin writings. For these reasons, Secret Writings stood at a threshold in the history of cuisine in Japan. It marked the beginning of a boom in culinary books written for a popular audience by a variety of authors outside of the ranks of h

nin writings. For these reasons, Secret Writings stood at a threshold in the history of cuisine in Japan. It marked the beginning of a boom in culinary books written for a popular audience by a variety of authors outside of the ranks of h ch

ch nin; and, it was the first h

nin; and, it was the first h ch

ch nin text to divulge publicly the “secrets” of the h

nin text to divulge publicly the “secrets” of the h ch

ch nin’s art, from ritual cutting to the ceremonial meals served at court. Secret Writings was also the last text to draw exclusively from the culinary texts of h

nin’s art, from ritual cutting to the ceremonial meals served at court. Secret Writings was also the last text to draw exclusively from the culinary texts of h ch

ch nin. Later authors who wrote about cutting ceremonies and ceremonial cuisine also incorporated information about published culinary books, such as Tales of Cookery, in their efforts to adapt h

nin. Later authors who wrote about cutting ceremonies and ceremonial cuisine also incorporated information about published culinary books, such as Tales of Cookery, in their efforts to adapt h ch

ch nin traditions for a popular audience.19 Hence, Secret Writings both marked the popularization of knowledge of the h

nin traditions for a popular audience.19 Hence, Secret Writings both marked the popularization of knowledge of the h ch

ch nins’ craft and signaled an end to their monopoly on culinary writings, as published culinary books began to dominate this field.

nins’ craft and signaled an end to their monopoly on culinary writings, as published culinary books began to dominate this field.

INSIDE A CULINARY TEXT

The characteristics of medieval culinary texts can be described in terms of what these writings lack in comparison to modern cookbooks or even early modern culinary books (ry ribon). First, culinary texts omit a preface that states the reason for the work’s compilation. They simply begin, and consist of simple entries on different topics listed consecutively. For example, Shij

ribon). First, culinary texts omit a preface that states the reason for the work’s compilation. They simply begin, and consist of simple entries on different topics listed consecutively. For example, Shij School Text on Food Preparation (hereafter Shij

School Text on Food Preparation (hereafter Shij School Text) consists of sixty topics listed one after another, ranging from the tools needed for carving ceremonies, to the different qualities of ingredients, to methods of food preparation and serving. In other words, culinary texts are lists of information.

School Text) consists of sixty topics listed one after another, ranging from the tools needed for carving ceremonies, to the different qualities of ingredients, to methods of food preparation and serving. In other words, culinary texts are lists of information.

Some of the entries in culinary texts are recipes, but these tend to lack the specificity of ones found in early modern culinary books, marking a second distinction between these two types of writings. The culinary book Tales of Cookery offers the following recipe for Snow Cakes (yuki mochi), which can serve as a useful point of comparison for measuring the recipes in earlier culinary writings by h ch

ch nin. This recipe is typical of ones found in published culinary books, in that it lists ingredients (although only a few books indicate the specific amounts to use) and provides some information about preparation (although not as much as modern cookbooks). These added details would be helpful to readers of culinary books, who would not necessarily have the same level of expertise as professional h

nin. This recipe is typical of ones found in published culinary books, in that it lists ingredients (although only a few books indicate the specific amounts to use) and provides some information about preparation (although not as much as modern cookbooks). These added details would be helpful to readers of culinary books, who would not necessarily have the same level of expertise as professional h ch

ch nin.

nin.

In contrast to this recipe, the ones in culinary texts by h ch

ch nin are terse to the point of being cryptic, as in the case for the recipe for sashimi from Shij

nin are terse to the point of being cryptic, as in the case for the recipe for sashimi from Shij School Text: “For sashimi: wasabi vinegar is for carp, ginger vinegar is for sea bream, smart-weed vinegar [tadesu] is for sea bass, mustard vinegar [mikeshizu] is for ray, and fish vinegar is for turbot.”21 This is the earliest recipe for cutting fish into thin strips to make sashimi, but the word sashimi itself is not defined, nor are directions provided for cutting the fish, which is the most important part of making the dish.22 The entry is meant for a chef who already knows how to prepare sashimi but needs to know the proper sauce to serve with it in an age before soy sauce became the usual accompaniment.23 In comparison, Tales of Cookery devotes an entire section to sashimi, providing twenty-seven recipes.24 Some of these are shorter than the one in Shij

School Text: “For sashimi: wasabi vinegar is for carp, ginger vinegar is for sea bream, smart-weed vinegar [tadesu] is for sea bass, mustard vinegar [mikeshizu] is for ray, and fish vinegar is for turbot.”21 This is the earliest recipe for cutting fish into thin strips to make sashimi, but the word sashimi itself is not defined, nor are directions provided for cutting the fish, which is the most important part of making the dish.22 The entry is meant for a chef who already knows how to prepare sashimi but needs to know the proper sauce to serve with it in an age before soy sauce became the usual accompaniment.23 In comparison, Tales of Cookery devotes an entire section to sashimi, providing twenty-seven recipes.24 Some of these are shorter than the one in Shij School Text, but others are much more descriptive, offering advice about cutting techniques. For example, the recipe for duck and goose sashimi in Tales of Cookery suggests two methods of preparation: steaming a whole bird and serving it with a sauce made from Japanese pepper, miso, and vinegar; or removing the bones and cutting it into small, round pieces and serving these with either a sauce made from wasabi and vinegar or one of ginger and miso.25

School Text, but others are much more descriptive, offering advice about cutting techniques. For example, the recipe for duck and goose sashimi in Tales of Cookery suggests two methods of preparation: steaming a whole bird and serving it with a sauce made from Japanese pepper, miso, and vinegar; or removing the bones and cutting it into small, round pieces and serving these with either a sauce made from wasabi and vinegar or one of ginger and miso.25

CULINARY TEXT OF THE YAMANOUCHI HOUSE

The first six texts listed in table 2 are largely compilations of recipes, excepting Culinary Text of the Yamanouchi House, which has two features that distinguish it from the others and make it more valuable for understanding h ch

ch nin cuisine. First, it includes general pronouncements about cooking, serving food, and table manners. Second, it provides diagrams of how dishes should be served in a formal banquet. The pronouncements, which appear at the beginning and end of the text, offer some interesting pointers, but they are too diverse in their subject matter to allow us to draw general conclusions. A few examples will suffice. According to one of the eight pronouncements at the beginning of the text: “At times when there has been a long interval of sake [drinking] after a light meal, it is appropriate to serve chilled barley noodles as a snack.” According to another one: “For a daimyo, be sure to serve chopsticks with the snack foods accompanying each round of drinks.”26 The text concludes with eleven more comments: “Don’t mix the fermented intestines of sea cucumbers [konowata] with dried sea cucumber intestines [iriko].” This instruction may have been prompted by concerns about taste or by fears of indigestion. Another concluding comment reminds readers that the only proper way to eat hawks is with the hands, not with chopsticks.27 These comments give us some idea about table manners and perhaps food taboos, but they are otherwise unremarkable. Other culinary texts have similar notes about manners and food safety, but these are interspersed with the recipes.

nin cuisine. First, it includes general pronouncements about cooking, serving food, and table manners. Second, it provides diagrams of how dishes should be served in a formal banquet. The pronouncements, which appear at the beginning and end of the text, offer some interesting pointers, but they are too diverse in their subject matter to allow us to draw general conclusions. A few examples will suffice. According to one of the eight pronouncements at the beginning of the text: “At times when there has been a long interval of sake [drinking] after a light meal, it is appropriate to serve chilled barley noodles as a snack.” According to another one: “For a daimyo, be sure to serve chopsticks with the snack foods accompanying each round of drinks.”26 The text concludes with eleven more comments: “Don’t mix the fermented intestines of sea cucumbers [konowata] with dried sea cucumber intestines [iriko].” This instruction may have been prompted by concerns about taste or by fears of indigestion. Another concluding comment reminds readers that the only proper way to eat hawks is with the hands, not with chopsticks.27 These comments give us some idea about table manners and perhaps food taboos, but they are otherwise unremarkable. Other culinary texts have similar notes about manners and food safety, but these are interspersed with the recipes.

The illustrations in Culinary Text of the Yamanouchi House are the second feature that distinguishes this work from other fifteenth- and sixteenth-century culinary texts, and these illustrations provide a context for understanding how dishes could be assembled to create a meal. The illustrations themselves are only diagrams. A square with flattened corners indicates a sanb , a ceremonial wooden tray on a stand.28 Circles and other shapes within the square indicate dishes on the tray. All the circles look similar, so it is fortunate that the contents of the dishes are labeled. Marginal comments next to the diagrams indicate that these trays of food are related: each is served simultaneously to a guest in a dining format used for elite banquets called the “main tray” style of serving (honzen ry

, a ceremonial wooden tray on a stand.28 Circles and other shapes within the square indicate dishes on the tray. All the circles look similar, so it is fortunate that the contents of the dishes are labeled. Marginal comments next to the diagrams indicate that these trays of food are related: each is served simultaneously to a guest in a dining format used for elite banquets called the “main tray” style of serving (honzen ry ri). Before studying examples of honzen meals in Culinary Text of the Yamanouchi House, and the important role of inedible foods in these banquets, we need to familiarize ourselves with the main-tray banqueting style.

ri). Before studying examples of honzen meals in Culinary Text of the Yamanouchi House, and the important role of inedible foods in these banquets, we need to familiarize ourselves with the main-tray banqueting style.

MAIN-TRAY-STYLE BANQUETING

As far back as at least the Nara period (710–84), the typical mode of dining for commoners and nobles was from an individual serving tray.29 The simplest of these trays might be little more than a wooden board called an oshiki, which allowed the commoner who sat on the floor of his home to keep his meal of soup and grains off of the ground. Aristocrats who sat on the floor to eat made use of more stylish trays with short supporting legs to raise their meals farther off of the floor, making them easier to consume. Picture scrolls such as Story Book of Hungry Ghosts (Gaki s shi) dating from the early Kamakura period (1185–1333) depict aristocrats dining from individual trays. By the Muromachi period (1336–1573), a style of banqueting had developed from customs surrounding formal shogunal visitations (onari) to high-ranking warriors and temples. It featured multiple trays of food served simultaneously to guests, beginning with a main tray (honzen) and several auxiliary trays served adjacent to it in front of the diner.30 This style of presentation became customary among elite samurai from the late fourteenth century and later spread to other classes, becoming, until the modern period, the most formal mode of dining.31 The structure of honzen dining, which featured rice, soup, pickles and side dishes, set the pattern for Japanese meals until after World War II.32

shi) dating from the early Kamakura period (1185–1333) depict aristocrats dining from individual trays. By the Muromachi period (1336–1573), a style of banqueting had developed from customs surrounding formal shogunal visitations (onari) to high-ranking warriors and temples. It featured multiple trays of food served simultaneously to guests, beginning with a main tray (honzen) and several auxiliary trays served adjacent to it in front of the diner.30 This style of presentation became customary among elite samurai from the late fourteenth century and later spread to other classes, becoming, until the modern period, the most formal mode of dining.31 The structure of honzen dining, which featured rice, soup, pickles and side dishes, set the pattern for Japanese meals until after World War II.32

Medieval and early modern sources listed a number of rules for honzen dining that hold true for most descriptions of these banquets.

- All the trays of food were served simultaneously in front of the seated diner.33 The main tray was placed directly in front of the guest. From the diner’s perspective, the second tray was placed to the right of the main tray, and the third tray was situated on the left. Additional trays could be placed behind the second and third trays.

- All the trays, including the main one, had to have at least one soup. Accordingly, the number of soups corresponded to the number of trays and vice versa.

- Only the main tray contained a serving of rice.34 Following custom, the rice was served on the left corner of the main tray closest to the guest, and the soup was placed on the right side.35

- The number of trays varied historically and according to the style of cooking, but three, five, or seven sets of trays per person were typical. The higher number of trays indicated a correspondingly more elaborate and formal banquet.36

- When more than three trays were used, the fourth tray was called the “additional tray” (yo no zen) to avoid using the number four (shi), which was a homonym for the word for death and therefore unlucky.

- Trays had a set number of side dishes on them, and the number varied according to the complexity of the meal. A typical pattern was “seven-five-three” (shichi go san), indicating that there were three trays (each containing one soup) with seven, five, and three side dishes on the first, second, and third trays, respectively.37

- Usually no alcohol was served during the honzen banquet. The banquet might be preceded by the “three ceremonial rounds of drinks” (shikisankon), which was a sake drinking ritual accompanied by snacks (sakana), or by less formal drinking. Drinking usually resumed after the honzen trays were removed and guests were enjoying more dishes in a relaxed atmosphere.38 Later they might take tea and refreshments and even tuck into heartier dishes as part of an “after meal” (godan). Elaborate banquets might have only three trays with a small number of dishes on them, but follow these with snacks and refreshments after the meal.39

- Besides the trays of snacks preceding and following the banquet, additional trays of food called hikimono (or hikidemono or hikide) were sometimes served with the honzen meal after the diners had started to eat. The function of these trays varied. They might be an individual tray served to each guest, or one for the host or his servants to pass among all the guests, or a tray of foods for the guests to take home as a souvenir to consume at another time.

João Rodrigues, a Portuguese Jesuit who traveled in Japan in the last decades of the sixteenth century, provides a concise portrait of a honzen meal that helps to contextualize these rules. His description of a main tray and two additional ones corresponds to the format found in Culinary Text of the Yamanouchi House:

The locations of the dishes on the trays held significance, according to Rodrigues, who comments, “Each dish has a fixed and suitable place on the table [i.e., tray] and a dish which is in one place is never put in another.”41 This comment explains why the author of Culinary Text of the Yamanouchi House took pains to draw the location of the dishes in the menus.

Manners dictated how the foods on the trays should be consumed. Transcript of Lord  kusa’s Oral Instructions (

kusa’s Oral Instructions ( kusadono yori s

kusadono yori s den no kikigaki) explains that diners should begin by “wetting their chopsticks in the soup on the main tray and picking up the rice bowl; after eating rice, sip the soup, but do not eat any morsels in it.” The guest would then take a little salt with the chopstick, eat some more rice, and sip more of the soup, before finally eating one of the side dishes on the main tray. But before trying the soup on the second tray, the guest had to take another bite of rice.42 As this text indicates, it took some knowledge of table manners to enjoy a honzen banquet politely, and guides to etiquette written for commoners in the Edo period dedicated considerable attention to the subject of dining so that commoners could gain confidence in this elaborate style of eating.43

den no kikigaki) explains that diners should begin by “wetting their chopsticks in the soup on the main tray and picking up the rice bowl; after eating rice, sip the soup, but do not eat any morsels in it.” The guest would then take a little salt with the chopstick, eat some more rice, and sip more of the soup, before finally eating one of the side dishes on the main tray. But before trying the soup on the second tray, the guest had to take another bite of rice.42 As this text indicates, it took some knowledge of table manners to enjoy a honzen banquet politely, and guides to etiquette written for commoners in the Edo period dedicated considerable attention to the subject of dining so that commoners could gain confidence in this elaborate style of eating.43

HONZEN MEALS IN CULINARY TEXT OF THE YAMANOUCHI HOUSE

For a concrete example of a honzen meal, we can turn to Culinary Text of the Yamanouchi House, which contains a description of two complete menus, including the snacks that precede and follow them.44 Culinary Text of the Yamanouchi House is not a record of actual meals, because its menus are not dated and only vague indications about seasonality are provided. Instead, this text, like all of the culinary writings by h ch

ch nin, was intended as a general model to follow in planning banquets. For this reason, the briefly noted recipes offer readers alternatives depending on the availability of ingredients.

nin, was intended as a general model to follow in planning banquets. For this reason, the briefly noted recipes offer readers alternatives depending on the availability of ingredients.

Since both of the menus in Culinary Text of the Yamanouchi House follow the same format of 5-4-3 (i.e., three trays, each with a soup, and with five, four, and three side dishes, respectively), we can focus our attention on just one of these. The menu translated here is the second of the two and is identified as one for summer.45

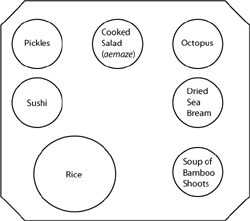

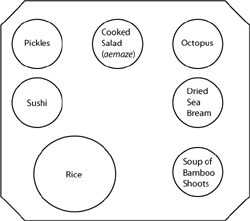

FIGURE 3. Main tray from Culinary Text of the Yamanouchi House (Yamanouchi ry risho)

risho)

The main tray includes the dishes shown in figure 3. The diagram of the “cut corner” (sumikiri) tray contains the prerequisites for honzen cuisine, reproduced from the perspective of the diner, who would find the soup in the nearest corner on the right of the tray and the rice in the nearest corner on the left. The cooked salad was a variation of “fish salad” (namasu), a typical dish for a main tray in the Muromachi period consisting of sliced fish and vegetables in a marinade. The type of fish is not specified, but Shij School Text, which stated that namasu was absolutely required for the main tray, includes recipes for Shredded Fish Salad (ito namasu) made from crucian carp, Yellow-Rose Fish Salad made of turbot, and Butter-Fish [managatsuo] Salad made with water pepper and vinegar.46 Turning to another dish on the main tray, Shij

School Text, which stated that namasu was absolutely required for the main tray, includes recipes for Shredded Fish Salad (ito namasu) made from crucian carp, Yellow-Rose Fish Salad made of turbot, and Butter-Fish [managatsuo] Salad made with water pepper and vinegar.46 Turning to another dish on the main tray, Shij School Text explains that, when octopus is served as a side dish, it should be cut into thin, round slices with the suction cups and skin removed.47 The sushi here is not specified either—the author of Shij

School Text explains that, when octopus is served as a side dish, it should be cut into thin, round slices with the suction cups and skin removed.47 The sushi here is not specified either—the author of Shij School Text opined that sweetfish (ayu), a freshwater fish, was best to use for sushi.48 Sweetfish appears in several dishes in this menu, as in the fish salad on the second tray, shown in figure 4.

School Text opined that sweetfish (ayu), a freshwater fish, was best to use for sushi.48 Sweetfish appears in several dishes in this menu, as in the fish salad on the second tray, shown in figure 4.

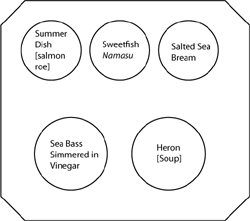

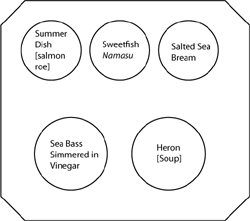

FIGURE 4. Second tray from Culinary Text of the Yamanouchi House

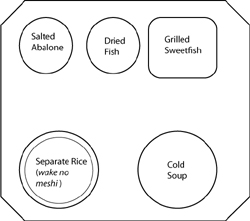

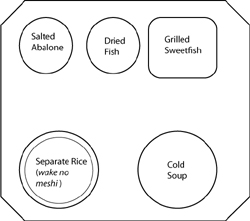

A notation provides some cooking instructions and suggestions for the “summer dish” (natsu mono) on the second tray. “Include something like a white pickling melon. An eggplant is also fine. Simmer it in a light soy sauce. Allow the salted sea bream to marinate in sake.” The “summer dish” is not specified in this menu, but a dish with the same name appears in Culinary Text of the Yamanouchi House with the gloss that it is salmon roe.49 No cooking directions are provided for the heron, but it is probably served in a soup, given its location in the right corner of the tray and the requirement for a soup on each tray.50 Sweetfish must have been a favorite, since it reappears on the third tray, shown in figure 5. The notation for this tray reads: “The soup is a fish soup. Any type of fish is fine. The dried fish is steamed and covered with sake. Serve the grilled sweetfish with green leaves underneath [as a garnish].” The rice on the third tray violates the rule that only the main tray should have rice, but in this case it appears that the cold soup is meant to be eaten as a sauce on top of the rice. Having an extra serving of rice on this tray would allow diners to keep the rice on the main tray unadulterated, a suitable neutral complement to the rest of the meal after pouring the soup on the rice on the third tray.51

FIGURE 5. Third tray from Culinary Text of the Yamanouchi House

This menu includes an additional tray (hikimono). As noted earlier, the contents of hikimono were meant for guests to take home with them, or they were passed around at the banquet. Since this tray contains a soup, it would have been difficult for guests to take this tray of foods home, indicating that the tray was either passed around to the guests or the hikimono is simply a fourth tray served to each guest individually.52

The notation indicates:

The handling of the foods in the final tray returns us to the central question of this chapter, about how many of the foods at a banquet were meant to be eaten. Given the directions for flavoring the dishes on the final tray, it appears that they were to be consumed. By the same logic, the lack of directions for other dishes on the other trays, notably the heron on the second tray and the cold soup and additional serving of rice on the third tray, leaves open the possibility that these were decorative dishes.

Fortunately, guests could rely on other culinary cues to determine whether foods were meant to be eaten or not. The first cue was the point when these foods appeared in a banquet. For instance, the snacks (sakana) served in the “ceremony of the three rounds of drinks” (shikisankon) that preceded formal banquets included several items that could not be consumed. The second cue regarding edibility was the physical appearance of the foods.

SHIKISANKON: INEDIBLE SNACKS ACCOMPANYING CEREMONIAL DRINKING

The “ceremony of the three rounds of drinks,” shikisankon, provides an example of the culinary rules that imparted transcendent qualities to food to enhance guests’ aesthetic appreciation of it and to provoke contemplation of its symbolic qualities. While the custom of drinking sake in Japan had long been an important means to celebrate new and old relationships, elite warriors in the Muromachi period developed that practice into the ceremony of the shikisankon. But it was actually the snacks accompanying the drinks that carried the most symbolic meaning.54 Each of the three rounds of sake was accompanied by snacks (sakana) that were not meant to be eaten, but which did have important significations they imparted, like magical talismans, on the participants of the shikisankon. Consequently, our main focus in the following description of shikisankon, derived from Culinary Text of the Yamanouchi House and other sources, is on the importance of these inedible foods in differentiating cuisine from ordinary food and its preparation and consumption.55 Cuisine was a practice of conspicuous nonconsumption.

João Rodriguez, a keen observer of social customs among the samurai elite, describes the importance of drinking wine (i.e., sake) as a ritual to cement relationships:

By sharing the same cup, the host and guest renewed their relationship or a married couple began theirs, since a similar ceremony of sipping from the same cup was used for weddings.

Shikisankon means “three rounds (kon) of drinking sake.” Each round consisted of draining a shallow cup (sakazuki) of sake three times.57 Thus, performing the “ceremony of three rounds” required drinking three cups of sake three times, or nine shallow cups of sake total. Each cup contained little more than a mouthful, allowing the event to retain its formality without degenerating into a drinking contest.58

Each of the three rounds of drinks included snacks to accompany the sake. It has been suggested that the word for “snack,” sakana, indicates that the foods originally served with the sake (saka) were vegetables (na), that later these snacks became prepared meats like fish and seafood.59 The origin of the word for “menu” (kondate), which dates to the first culinary text by h ch

ch nin, namely, the 1489 Shij

nin, namely, the 1489 Shij School Text, is as a list of foods to accompany drinks. Or, as Sh

School Text, is as a list of foods to accompany drinks. Or, as Sh sekiken S

sekiken S ken, the author of a culinary book published in 1730, indicated, a menu was the “plan for the rounds of drinks.”60 From the Muromachi period onward, typical shikisankon snacks included pickled apricots (umeboshi), abalone, konbu seaweed, dried chestnuts (kachiguri), and dried squid. All these foods have important symbolic meanings.

ken, the author of a culinary book published in 1730, indicated, a menu was the “plan for the rounds of drinks.”60 From the Muromachi period onward, typical shikisankon snacks included pickled apricots (umeboshi), abalone, konbu seaweed, dried chestnuts (kachiguri), and dried squid. All these foods have important symbolic meanings.

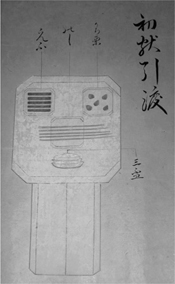

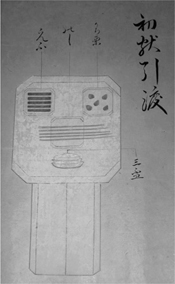

Culinary Text of the Yamanouchi House offers diagrams of two trays for shikisankon.61 Figure 6 reveals three cups, stacked on top of one another, one for each round of drinks, accompanied by other foods. Unlike the banquet trays that would be served individually to each guest, there was one common tray bearing the sake cups and snacks for all the guests to use.62 Sharing the same cup allowed for the “union of hearts,” to recall Rodrigues’s words.

In contrast to the rest of the meal, which presented a variety of different dishes in a unique combination, the composition of the shikisankon was standard, allowing us to reference an illustration from an early Edo period culinary text, which is nearly identical to the version in Culinary Text of the Yamanouchi House. Accompanying the sake cups in that illustration are, clockwise from the top, five strips of dried konbu seaweed, five dried chestnuts, and five strips of dried abalone, all on pieces of white paper.63 Excepting the number of konbu, which numbered only two pieces in the version in Culinary Text of the Yamanouchi House, this Edo period painting of a shikisankon is practically identical, for these snacks were typical of those served for shikisankon in the Muromachi and Edo periods.64 All these foods share the distinct characteristic that none of them could be consumed when served in this form. Since these were dried foods, they would have to be soaked in water before they were eaten, and the process would take several hours at minimum. The dried chestnuts, for instance, would have to be soaked overnight before being simmered to make them edible.65 Konbu still is the chief ingredient for making stock, prepared by placing the seaweed in boiling water, but unless it is cooked, dried konbu is too tough to eat. The dried abalone could not be eaten until it was soaked in water and then steamed, boiled, or eaten raw, or cut into small pieces to be used as a flavoring.

FIGURE 6. Shokon hikiwatashi (shikisankon), from Scroll of Seven Trays and Nineteen Rounds of Drinks (Shichi no zen j ky

ky kon no maki), Edo period. Courtesy of Mankamer

kon no maki), Edo period. Courtesy of Mankamer .

.

Since the shikisankon snacks could not be eaten, they were included for the symbolic values derived from their names. Konbu seaweed, often called kobu, as it is in Culinary Text of the Yamanouchi House, brought to mind the word happiness (yorokobu). The abalone was dried, pounded flat, and cut into long slices. Transforming a shellfish best eaten raw into a dried, flat form not only preserved it and allowed it to be eaten in places that, like Kyoto, were removed from the ocean, but it also added important symbolic meanings and some interesting visual puns. Since it could be stretched out, abalone promised an extended lifespan. Dried abalone was also a military food, probably because, as a preserved food, it could be easily taken on a campaign. The word for abalone in this form was noshi awabi, or simply noshi as it was used in Culinary Text of the Yamanouchi House, a word that also meant “victory.” When the same preparation was called “flattened abalone,” uchi awabi, the words conjured up the idea that one would “smite”(utte) one’s enemies. These meanings made abalone an auspicious gift for warriors. Dried abalone was often used as a decoration on gifts, a custom preserved today in the designs on gift envelopes and the wrapping paper used by many Japanese department stores called “abalone-paper” (noshigami). Like the names of these other foods, the word for dried chestnuts (kachiguri)—made from mountain chestnuts (sasaguri) that were first dried, then roasted, and then pounded in a mortar to remove the astringent skin—was a homonym. Kachi not only meant dried but also meant victory.66

Martial associations with the shikisankon snacks may date to as early as the Heian period, when warriors were toasted with sake and snacks on festival days and before going into battle.67 Flattened abalone was one of the snacks served to accompany drinking at the annual New Year’s feast hosted by the Kamakura bakufu for retainers (gokenin).68 The sixteenth-century culinary text Transcript of Lord  kusa’s Oral Instructions includes a pithy statement about the military symbolism of the chestnuts, abalone, and konbu, respectively: “On departing for battle, smiting [utte], winning [katte], and rejoicing [yorokobu] are joined together.” The same text notes later: “On returning from battle, winning, smiting, and rejoicing are joined together.”69 This indicates the order in which these snacks were to be handled to ensure their felicitous properties at drinking ceremonies either before departing for a battle or after returning from one. The 1714 publication Complete Manual of Cuisine of Our School (T

kusa’s Oral Instructions includes a pithy statement about the military symbolism of the chestnuts, abalone, and konbu, respectively: “On departing for battle, smiting [utte], winning [katte], and rejoicing [yorokobu] are joined together.” The same text notes later: “On returning from battle, winning, smiting, and rejoicing are joined together.”69 This indicates the order in which these snacks were to be handled to ensure their felicitous properties at drinking ceremonies either before departing for a battle or after returning from one. The 1714 publication Complete Manual of Cuisine of Our School (T ry

ry setsuy

setsuy ry

ry ri taizen) expounds further on these associations: “Kobu is the widest of all seaweeds; since it is so large, it is auspicious. Dried chestnuts are felicitous due to their association with the word victory. It is said that there was a hermit named T

ri taizen) expounds further on these associations: “Kobu is the widest of all seaweeds; since it is so large, it is auspicious. Dried chestnuts are felicitous due to their association with the word victory. It is said that there was a hermit named T nansei who collected and ate these and lived seven hundred years.”70

nansei who collected and ate these and lived seven hundred years.”70

When other snacks were used for shikisankon, these too had important symbolic meanings. Dried squid (surume) suggested the word suehirogari, meaning “enjoying increased prosperity.” Dried bonito flakes (katsuo bushi), also used to make soup stock and as a flavoring, evoked the same word for victory (katsu) as dried chestnuts.71 Like the other shikisankon snacks, these, too, were dried foods; but unlike them they could be consumed immediately.72

The inedible snacks of the shikisankon are analogous to the sculptures of marzipan, lard, and sugar called “subtleties” that graced royal banquets in thirteenth-century Europe. Anthropologist Sidney Mintz has described these as “message-bearing objects that could be used to make a special point.”73 In both contexts, the presence of such culinary symbols bespoke martial prowess and political authority. The only difference is that the Japanese did not eat their symbols, and this gave them greater transcendence, allowing their properties to endure longer by virtue of not being consumed. Indeed, that warriors participating in the shikisankon did not consume these foods, but instead secreted them on their persons as if they were protective amulets, deserves note for being not only a way for the foods to outlast the banquets but also a way for their bearers to enjoy the martial qualities of these snacks and persevere in any challenge they might encounter. João Rodrigues notes that, at formal New Year’s celebrations, konbu, chestnuts, dried squid, and other foods that “indicate a good omen” were served to guests, but that these were not consumed. Instead, “everybody takes one or two grains [of food] with two fingers of his right hand and puts them in his mouth, or at least pretends to put them there without actually doing so.”74 The sixteenth-century h ch

ch nin text Transcript of Lord

nin text Transcript of Lord  kusa’s Oral Instructions, too, indicates that guests should mime eating the snacks and discreetly tuck them into a sleeve or fold of a kimono (kaich

kusa’s Oral Instructions, too, indicates that guests should mime eating the snacks and discreetly tuck them into a sleeve or fold of a kimono (kaich ): “Take the second strand of flattened abalone from the front and bring it up to your mouth, and then tuck it away into your pocket.” After pouring sake into the top cup and taking three drinks, the guest took up the second sake cup and chose the middle of the five chestnuts; this he also mimed eating before secreting it away like the abalone. The instructions for handling the konbu were similar. As noted earlier, the drinker took up these snacks in the order in which they would be most important to a samurai in battle, signifying that he would go forth and smite the enemy (noshi, abalone), be victorious (katsu, chestnuts), and celebrate (kobu, konbu).

): “Take the second strand of flattened abalone from the front and bring it up to your mouth, and then tuck it away into your pocket.” After pouring sake into the top cup and taking three drinks, the guest took up the second sake cup and chose the middle of the five chestnuts; this he also mimed eating before secreting it away like the abalone. The instructions for handling the konbu were similar. As noted earlier, the drinker took up these snacks in the order in which they would be most important to a samurai in battle, signifying that he would go forth and smite the enemy (noshi, abalone), be victorious (katsu, chestnuts), and celebrate (kobu, konbu).

Guidebooks to etiquette published in the Edo period disseminated the procedure for handling shikisankon snacks so that commoners became aware of these practices. One of the earliest of these texts was Treasury for Women (Onna ch h

h ki), a popular compendium on behavior and general knowledge for women by Namura J

ki), a popular compendium on behavior and general knowledge for women by Namura J haku (1674–1748) first published in 1692. J

haku (1674–1748) first published in 1692. J haku’s text reveals that commoners had adopted the shikisankon for wedding ceremonies but still needed guidance about what to do with the snacks. He writes, “The groom and bride consume the three rounds of drinks [shikisankon],” but, “they should only pretend to eat the food.”75 Another guidebook, Chastity Bookstore House for Teaching Women Loyalty (Onna ch

haku’s text reveals that commoners had adopted the shikisankon for wedding ceremonies but still needed guidance about what to do with the snacks. He writes, “The groom and bride consume the three rounds of drinks [shikisankon],” but, “they should only pretend to eat the food.”75 Another guidebook, Chastity Bookstore House for Teaching Women Loyalty (Onna ch ky

ky misao bunko), published in 1801, provides women with more explicit instructions about what to do with the snacks: “Delicacies [sakana] one should receive with the hands, and take them while folding a nose [blowing] paper, put [the delicacies] inside [the paper], place [the latter on the floor] at one’s side, and take it along at the time one stands up.”76 Edo-period commoners employed shikisankon for occasions other than weddings, too, such as the first formal meeting of a client and a high-ranking courtesan, so it became a custom used for many different purposes.77

misao bunko), published in 1801, provides women with more explicit instructions about what to do with the snacks: “Delicacies [sakana] one should receive with the hands, and take them while folding a nose [blowing] paper, put [the delicacies] inside [the paper], place [the latter on the floor] at one’s side, and take it along at the time one stands up.”76 Edo-period commoners employed shikisankon for occasions other than weddings, too, such as the first formal meeting of a client and a high-ranking courtesan, so it became a custom used for many different purposes.77

A FEW EDIBLE SNACKS ALONG WITH SAKE

In contrast to the inedible symbols used in the shikisankon, a second tray of tasty dishes, meant to be eaten as an accompaniment for further drinking, is depicted in Culinary Text of the Yamanouchi House.78 Muromachi-period records indicate that as many as seventeen additional rounds of drinks could follow the conclusion of the shikisankon.79 However, edible foods were served only after the third or fifth round of drinks. Longer drinking bouts would have necessitated that participants have something to eat, both to stimulate further drinking and to ensure that they did not pass out from having too much alcohol in their empty stomachs. The formality of the initial shikisankon would have also been difficult to maintain after so many rounds of drinks, adding another reason why the drinkers might have been inclined to consume the snacks they were served.

The illustration of the second tray in Culinary Text of the Yamanouchi House (not reproduced here) shows five dishes, three small dishes further away from the guest and two larger ones closer. The former include:

Fish cake (kamaboko) |

Turbot (sazae) |

Potato bulbs on skewers (nukago sashi) |

A notation explains that three or five servings of fish cake should be served. A separate note explained that three or five potato bulbs should be served, so the portions of these foods were probably meant to correspond to one another. The ingredients of the fish cake are not specified, but fish cake can be made from any fish mashed into a paste. The paste is then thickened with a starch, dyed, and modeled into a shape.80 The potato bulbs (also called mukago) are small growths that appear on yam vines, rather than small potatoes. Shij School Text indicates that, when kamaboko and potato bulbs on skewers were served together, they should be accompanied by small pieces of paper used to hold them while eating, called kisoku (literally “turtles’ feet”), the design of which should suit the rank of the guest.81 Culinary Text of the Yamanouchi House also provides possible substitutions for the turbot if it was unavailable: “fermented sea cumber intestines [konowata] or blue crab [gazame, also called gazami].” Konowata was an especially esteemed dish, one of the top three delicacies of the Edo period.82

School Text indicates that, when kamaboko and potato bulbs on skewers were served together, they should be accompanied by small pieces of paper used to hold them while eating, called kisoku (literally “turtles’ feet”), the design of which should suit the rank of the guest.81 Culinary Text of the Yamanouchi House also provides possible substitutions for the turbot if it was unavailable: “fermented sea cumber intestines [konowata] or blue crab [gazame, also called gazami].” Konowata was an especially esteemed dish, one of the top three delicacies of the Edo period.82

The two larger dishes on the tray were:

Separate rice (wake no meshi) |

Cold soup (hiyashiru)83 |

Recall that the honzen menu also had a notation for a dish of “separate rice” served with cold soup. The dish appears to be characteristic of Culinary Text of the Yamanouchi House but atypical of most honzen banquets, which restricted rice to the main tray. Unfortunately, the annotations do not provide further clarification. As noted earlier, cold soups were a staple of Muromachi-period banquets, though less popular in the Edo period. The ingredients in the one here are unspecified, so it could be a decorative dish, but Shij School Text contains a recipe for one made from oysters and sea cucumber that sounds tasty enough to eat.84 As before, the soup could also be meant as a sauce for the rice.

School Text contains a recipe for one made from oysters and sea cucumber that sounds tasty enough to eat.84 As before, the soup could also be meant as a sauce for the rice.

After the initial drinking session, the party adjourned to another room to begin the honzen banquet. When a Muromachi shogun paid a formal visitation (onari) to a vassal or a religious institution, the shikisankon was a relatively private affair that occurred in a small room featuring Chinese art objects. The banquet that followed occurred in a larger room called the hiroma.85

DECORATIVE SERVINGS AT HONZEN BANQUETS

The second indication of whether something could be eaten at a honzen banquet was the appearance of the dish itself. Writing about earlier forms of banqueting (i.e., before the rise to power of Oda Nobunaga in the late 1560s), João Rodrigues explains that banquets of three, five, and seven trays often had many dishes that were not meant to be consumed: “In these banquets many of the dishes were served on plates in the form of pyramids neatly arranged with their corners as in the Chinese fashion, and it was from China that they derived their origin; but they were served only for decoration and were there to be looked at and not eaten.”86 The type of presentation that Rodrigues described is known by the generic term high serving (takamori), a way of serving food that dated back to at least the Heian period and indeed originated in China. One theory holds that this pile of food symbolized the mountain home of a Chinese immortal, but medieval and early modern sources provide other interpretations.87

Takamori measured approximately fifteen to eighteen centimeters in height and were found at some of the most elaborate banquets for the aristocratic and samurai elite of the Muromachi and Edo periods. When we consider the definition of cuisine (ry ri) as denoting more that simply a style of cooking, as including the way in which food could be appreciated intellectually and artistically, takamori played an important role in Japan’s culinary history by adding visual and symbolic depth to banquets, thereby differentiating these occasions from ordinary meals lacking these special dishes. The special function of takamori in the artistic and intellectual appreciation of a meal was confirmed by the fact that takamori were created especially for their decorative and symbolic purposes and were not meant to be eaten.

ri) as denoting more that simply a style of cooking, as including the way in which food could be appreciated intellectually and artistically, takamori played an important role in Japan’s culinary history by adding visual and symbolic depth to banquets, thereby differentiating these occasions from ordinary meals lacking these special dishes. The special function of takamori in the artistic and intellectual appreciation of a meal was confirmed by the fact that takamori were created especially for their decorative and symbolic purposes and were not meant to be eaten.

Culinary historians  tsubo Fujiyo and Akiyama Teruko, who have researched the history of takamori, indicate that these types of servings were derived from earlier customs of religious offerings. It is still a custom today at some shrines and temples to offer fruits, nuts, and other foods piled in high offerings to the deities and Buddhas.

tsubo Fujiyo and Akiyama Teruko, who have researched the history of takamori, indicate that these types of servings were derived from earlier customs of religious offerings. It is still a custom today at some shrines and temples to offer fruits, nuts, and other foods piled in high offerings to the deities and Buddhas.  tsubo and Akiyama indicate this mode of serving was incorporated in honzen banquets for imperial rituals. For example, the emperor was presented with a ceremonial meal on the second day of the new year called daish

tsubo and Akiyama indicate this mode of serving was incorporated in honzen banquets for imperial rituals. For example, the emperor was presented with a ceremonial meal on the second day of the new year called daish jinomono, and another the next day for a long-life ritual called “tooth strengthening” (ohagatame), reflecting the idea that healthy teeth are important for a long lifespan. The emperor ate neither of these trays of food, which were served in the takamori style. According to a late Heian-period description of the imperial ohagatame rite, Collection of Illustrated Guidelines for Miscellaneous Procedures (Ruij

jinomono, and another the next day for a long-life ritual called “tooth strengthening” (ohagatame), reflecting the idea that healthy teeth are important for a long lifespan. The emperor ate neither of these trays of food, which were served in the takamori style. According to a late Heian-period description of the imperial ohagatame rite, Collection of Illustrated Guidelines for Miscellaneous Procedures (Ruij zatsuy

zatsuy sh

sh sashizu), foods served takamori style included separate plates stacked with slices of venison, wild boar, sea bream, carp, and whole raw vegetables (see plate 3).88 Instead of even trying to eat these foods, the emperor merely tapped the tray with his chopsticks. Directions for this procedure appear in Annual Rites of the Kemmu Era (Kemmu nench

sashizu), foods served takamori style included separate plates stacked with slices of venison, wild boar, sea bream, carp, and whole raw vegetables (see plate 3).88 Instead of even trying to eat these foods, the emperor merely tapped the tray with his chopsticks. Directions for this procedure appear in Annual Rites of the Kemmu Era (Kemmu nench gy

gy ji), which dates from 1330: “Remove the chopsticks from the tray, or pretend to remove them, and signify that you have eaten by making a noise with the chopsticks.”89 It appears that the use of food in ceremonies—whether an offering to deities and Buddhas or an offering used in a longevity ritual for the emperor—required that it not be eaten; and arranging it in a “high serving” marked the food for this purpose.

ji), which dates from 1330: “Remove the chopsticks from the tray, or pretend to remove them, and signify that you have eaten by making a noise with the chopsticks.”89 It appears that the use of food in ceremonies—whether an offering to deities and Buddhas or an offering used in a longevity ritual for the emperor—required that it not be eaten; and arranging it in a “high serving” marked the food for this purpose.

Other modes of service likewise marked dishes as being for ceremonial or display purposes rather than for consumption, and the use of these extended beyond the court.  tsubo and Akiyama supply an example by citing a banquet menu for a New Year’s celebration served in the Hosokawa warrior house in the H

tsubo and Akiyama supply an example by citing a banquet menu for a New Year’s celebration served in the Hosokawa warrior house in the H reki period (1751–64), as described by one of its descendants, Hosokawa Morisada (1912–2005).90 The same New Year’s meal was served for several consecutive days and consisted of three trays with five, five, and three side dishes, respectively:

reki period (1751–64), as described by one of its descendants, Hosokawa Morisada (1912–2005).90 The same New Year’s meal was served for several consecutive days and consisted of three trays with five, five, and three side dishes, respectively:

The dishes called “servings” (mori), and a few others here, were not meant to be eaten. Hosokawa states this clearly in reference to the menu: “It was customary to have some things that would not be touched: on the main tray, the sea bream serving, the serving of pickles, and the sardines; on the second tray, the dried squid cluster serving, the spiral shellfish, and the pheasant serving; and on the third tray, the spiny lobster in the shape of a boat, the whale cleat-wood serving, and the duck wing serving were not meant for eating, but were a type of decoration that one did not touch with chopsticks, according to custom.” (See plate 4.) It seems only the soups, the rice, and a few other things could be consumed. The foods that had been consumed would have to be replaced with every meal, but the decorative dishes could be reused for several days in a row.93 After surveying similar Edo period banquets for the warrior elite,  tsubo and Akiyama conclude that “trays with high servings are best considered to be decorations exhibiting opulence rather than food.”94

tsubo and Akiyama conclude that “trays with high servings are best considered to be decorations exhibiting opulence rather than food.”94

However, the issue of serving style is more complicated than the single term high serving (takamori) suggests. In the aforementioned example the dishes are not described as high servings: the word mori is instead a suffix attached to certain words denoting them as “servings.” Moreover, the term high serving does not appear as a significant category or descriptive term in h ch

ch nin culinary texts. Instead, these texts indicate that there are two categories of servings. The first category was decorative dishes called servings (mori), akin to those in the previous menu for the Hosokawa family.95 This mode of serving highlighted the principle ingredient by presenting it in a creative way, such as “spiny lobster in the shape of a boat” (ebi [no] funamori). Since these came in a variety of shapes, high serving is a misnomer, especially since h

nin culinary texts. Instead, these texts indicate that there are two categories of servings. The first category was decorative dishes called servings (mori), akin to those in the previous menu for the Hosokawa family.95 This mode of serving highlighted the principle ingredient by presenting it in a creative way, such as “spiny lobster in the shape of a boat” (ebi [no] funamori). Since these came in a variety of shapes, high serving is a misnomer, especially since h ch

ch nin used more specific terms. The second category describes the abstract shapes that pieces of foods could be sculpted into. Physically these were “high servings,” measuring about half a foot in height, but h

nin used more specific terms. The second category describes the abstract shapes that pieces of foods could be sculpted into. Physically these were “high servings,” measuring about half a foot in height, but h ch

ch nin again used more specific and poetic terms to describe them. In contrast to the first type of serving—which emphasized naturalistic depictions of ingredients as culinary sculpture, for example, by adding feathered wings to a cooked duck (kamo hamori) to make it appear as if it might fly away—the second category of servings evoked more abstract interpretations farther removed from the meanings of the actual foods themselves. Each category must be evaluated if we are to understand that, in defining a cuisine, Japan’s elite food culture placed as much emphasis on decoration and symbolism as it did on cooking and eating.

nin again used more specific and poetic terms to describe them. In contrast to the first type of serving—which emphasized naturalistic depictions of ingredients as culinary sculpture, for example, by adding feathered wings to a cooked duck (kamo hamori) to make it appear as if it might fly away—the second category of servings evoked more abstract interpretations farther removed from the meanings of the actual foods themselves. Each category must be evaluated if we are to understand that, in defining a cuisine, Japan’s elite food culture placed as much emphasis on decoration and symbolism as it did on cooking and eating.

LOBSTER BOATS, FLYING DUCKS, AND OTHER DECORATIVE SERVINGS