CHAPTER 7

Deep Thought Wheat Gluten and Other Fantasy Foods

By the mid-eighteenth century, published recipe books focused increasingly on the intellectual appreciation of food. Culinary historian Harada Nobuo describes these works as full of “amusements” (asobi), exemplified by the abundance of puns and wordplay in the names of recipes, particularly in the recipe collections Delicacies from the Mountains and Seas (Ry ri sankaiky

ri sankaiky , 1750) and Anthology of Special Delicacies (Ry

, 1750) and Anthology of Special Delicacies (Ry ri chinmish

ri chinmish , 1764). He also includes the so-called hundred tricks (hyakuchin) texts, a series of books published beginning in the 1780s that featured a hundred recipes for a single ingredient, albeit he finds them more technical than other texts written for amusement. In regard to all these works, Harada says that, “at this point, cuisine [ry

, 1764). He also includes the so-called hundred tricks (hyakuchin) texts, a series of books published beginning in the 1780s that featured a hundred recipes for a single ingredient, albeit he finds them more technical than other texts written for amusement. In regard to all these works, Harada says that, “at this point, cuisine [ry ri] transcended a reliance on gustatory enjoyment. It became possible to enjoy cuisine as an abstraction, seeking satisfaction in information that appealed to the visual senses.”1 While noting the significance of this development, Harada nonetheless takes it as a sign that Japan’s culinary culture has entered a period of decline. “The culinary culture . . . was characterized by an emphasis on ‘playful’ elements; thus, it lacked real substance and merely proceeded along the same line of ever more refined, purely secondary and inconsequential aspects of food preparation.”2 If we limit the definition of cuisine (ry

ri] transcended a reliance on gustatory enjoyment. It became possible to enjoy cuisine as an abstraction, seeking satisfaction in information that appealed to the visual senses.”1 While noting the significance of this development, Harada nonetheless takes it as a sign that Japan’s culinary culture has entered a period of decline. “The culinary culture . . . was characterized by an emphasis on ‘playful’ elements; thus, it lacked real substance and merely proceeded along the same line of ever more refined, purely secondary and inconsequential aspects of food preparation.”2 If we limit the definition of cuisine (ry ri) to cooking techniques as Harada does here, then an intellectual appreciation of food may be inconsequential. However, the story of Japanese cuisine examined in this book has shown that contemplating or fantasizing with food is central to cuisine. To recall Priscilla Parkhurst Ferguson’s pithy definition, cuisine is “the cultural code that enables societies to think with and about the food they consume.”3 Consequently, rather than signaling a decline in culinary culture, the recipe books of the late Edo period that Harada criticizes represent a blossoming of popular thinking about food as they reveal new ways to enjoy food intellectually. This flowering of inter est in cuisine coincided with a boom in cookbook publishing that began in the 1770s and peaked around 1800, but continued strong until the 1850s, shortly before the end of the Tokugawa period.4

ri) to cooking techniques as Harada does here, then an intellectual appreciation of food may be inconsequential. However, the story of Japanese cuisine examined in this book has shown that contemplating or fantasizing with food is central to cuisine. To recall Priscilla Parkhurst Ferguson’s pithy definition, cuisine is “the cultural code that enables societies to think with and about the food they consume.”3 Consequently, rather than signaling a decline in culinary culture, the recipe books of the late Edo period that Harada criticizes represent a blossoming of popular thinking about food as they reveal new ways to enjoy food intellectually. This flowering of inter est in cuisine coincided with a boom in cookbook publishing that began in the 1770s and peaked around 1800, but continued strong until the 1850s, shortly before the end of the Tokugawa period.4

Although these writings focused more on the abstract meanings of food, the “amusing” cookbooks of the late-Edo period did not represent a radical departure from earlier culinary writings.5 In the first place, all cookbooks in the Edo period present ideal uses for food, not the reality of what people actually cooked and ate. Second, an appreciation for how food could signify abstract qualities did not begin in the eighteenth century; it was prominent in earlier culinary writings. For example, the inedible dishes found in elite banquets described in medieval culinary texts (ry risho) confirm the importance of foods that represented qualities such as marital felicity and martial virtues. Likewise, the culinary books of the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries depicted both banquets and dishes that could be prepared and consumed by only a fraction of the readership of these works, making these foods vicarious abstractions for the remainder of their audience, who could only appreciate them secondhand by reading about them. In that light, the novelty of the late-eighteenth-century cookbooks rests less in their playful use of abstract qualities associated with certain foods and more in the fact that their authors, recognizing the capacity of existing culinary rules to make food signify other things, incorporated new references into the culinary code, including poetry, natural phenomena, and geography.

risho) confirm the importance of foods that represented qualities such as marital felicity and martial virtues. Likewise, the culinary books of the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries depicted both banquets and dishes that could be prepared and consumed by only a fraction of the readership of these works, making these foods vicarious abstractions for the remainder of their audience, who could only appreciate them secondhand by reading about them. In that light, the novelty of the late-eighteenth-century cookbooks rests less in their playful use of abstract qualities associated with certain foods and more in the fact that their authors, recognizing the capacity of existing culinary rules to make food signify other things, incorporated new references into the culinary code, including poetry, natural phenomena, and geography.

SOLID GOLD SOUP AND DEEP THOUGHT WHEAT GLUTEN

Exemplifying trends in late Edo period cookbooks written to amuse readers, Delicacies from the Mountains and Seas (Ry ri sankaiky

ri sankaiky ), published in 1750, was a culinary book meant to be read leisurely from cover to cover or opened randomly, as opposed to one designed to provide quick access to information about cooking. In contrast to earlier cookbooks like Tales of Cookery (Ry

), published in 1750, was a culinary book meant to be read leisurely from cover to cover or opened randomly, as opposed to one designed to provide quick access to information about cooking. In contrast to earlier cookbooks like Tales of Cookery (Ry ri monogatari, 1643) and Assembly of Standard Cookery Writings (G

ri monogatari, 1643) and Assembly of Standard Cookery Writings (G rui nichiy

rui nichiy ry

ry rish

rish , 1689), which organized recipes according to their principle ingredient or by cooking techniques, Delicacies from the Mountains and Seas presented 230 recipes in five volumes, but without any clear organization that would make a specific recipe easy to find.6 Remarkably, the model for Delicacies from the Mountains and Seas was not another cookbook, although the author, Hakub

, 1689), which organized recipes according to their principle ingredient or by cooking techniques, Delicacies from the Mountains and Seas presented 230 recipes in five volumes, but without any clear organization that would make a specific recipe easy to find.6 Remarkably, the model for Delicacies from the Mountains and Seas was not another cookbook, although the author, Hakub shi (n.d.), certainly borrowed recipes from earlier culinary writings. Instead, the work appears to be patterned after an ancient Chinese bestiary, which contained mythical creatures that could not be pigeonholed into conventional categories. Writing in the 1967 preface to a similar bestiary, the Book of Imaginary Beings, Jorge Luis Borges commented that “a book of this kind is unavoidably incomplete; each new edition forms the basis of future editions, which themselves may grow endlessly.”7 Hakub

shi (n.d.), certainly borrowed recipes from earlier culinary writings. Instead, the work appears to be patterned after an ancient Chinese bestiary, which contained mythical creatures that could not be pigeonholed into conventional categories. Writing in the 1967 preface to a similar bestiary, the Book of Imaginary Beings, Jorge Luis Borges commented that “a book of this kind is unavoidably incomplete; each new edition forms the basis of future editions, which themselves may grow endlessly.”7 Hakub shi took a similar view, for he published a sequel to Delicacies from the Mountains and Seas with an identical format fourteen years later, titled Anthology of Special Delicacies (Ry

shi took a similar view, for he published a sequel to Delicacies from the Mountains and Seas with an identical format fourteen years later, titled Anthology of Special Delicacies (Ry ri chinmish

ri chinmish ). The latter volume also contains 230 recipes in five volumes, and the same Kyoto publisher printed both books. Information about the author in the preface identifies him as living in the eastern part of Kyoto and as “proficient in the ways” of cooking.8 This reference may indicate that the author was a chef working in a restaurant in that part of the city, of which there were several at that time.9 Another possibility is that Hakub

). The latter volume also contains 230 recipes in five volumes, and the same Kyoto publisher printed both books. Information about the author in the preface identifies him as living in the eastern part of Kyoto and as “proficient in the ways” of cooking.8 This reference may indicate that the author was a chef working in a restaurant in that part of the city, of which there were several at that time.9 Another possibility is that Hakub shi is the pen name of a professional writer who was an amateur chef.10 These conclusions are based on his two culinary books, because no other historical records of the author are known.

shi is the pen name of a professional writer who was an amateur chef.10 These conclusions are based on his two culinary books, because no other historical records of the author are known.

The title Delicacies from the Mountains and Seas references the ancient Chinese book of legends and geographical writings, Guideways through Mountains and Streams (Sankai ky , Shanhaijing in Chinese), compiled from the fourth century to first century B.C.E.11 This text in eighteen volumes is attributed to Yu the Great (trad. reign 1989–81 B.C.E.), founder of the mythic Xia dynasty. Yu is said to have written this book with the assistance of a helper named Boyi, whom the Japanese called Hakueki, a name that may have been the inspiration for the penname Hakub

, Shanhaijing in Chinese), compiled from the fourth century to first century B.C.E.11 This text in eighteen volumes is attributed to Yu the Great (trad. reign 1989–81 B.C.E.), founder of the mythic Xia dynasty. Yu is said to have written this book with the assistance of a helper named Boyi, whom the Japanese called Hakueki, a name that may have been the inspiration for the penname Hakub shi used.

shi used.

Not only the title but also the ancient Chinese text certainly influenced the structure of the later culinary books. The Chinese Guideways can be described as a bestiary, but it offers more than just information about creatures. It provides lore about some “500 creatures that inhabit approximately 550 mountains, 300 rivers, 95 foreign lands and tribes; it lists 130 kinds of pharmaceuticals (to prevent some 70 illnesses), 435 plants, 90 metals and minerals” in a compendium that one commentator called “the ancestor of all discussions of the strange.” The mythical creatures include the nine-tail fox, the Zhu bird, an owl with human hands, and the Tuan-fish—a carp that oinks like a pig. These beasts confound simple categorization since they are hybrids, fusions of animals and man, which “represent another, overlapping order with its own principles,” in the words of one modern expert on the text.12

Instead of strange beasts that defy classification, Delicacies from the Mountains and Seas contains dishes without apparent connections to one another that are hybrids of the mundane and fantastic. The list of dishes in the fifth volume of Delicacies from the Mountains and Seas is representative of the character of both volumes and the types of recipes in them:13

In this list and throughout both books, recipes for sushi, pickles, sake, sweets, fish salads, and soups are mixed together rather than consigned to different sections of the text as in earlier cookbooks, like Tales of Cookery and Assembly of Standard Cookery Writings. The latter two works also title recipes according to main ingredient or cooking technique, but in Delicacies from the Mountain and Seas the names of the dishes alone attract attention for their mysterious resonance.14 Some of these dishes, such as Fried Wheat Gluten and sushi, are recognizable from early cookbooks. Fried Wheat Gluten, for example, is mentioned in Tales of Cookery, and Assembly of Standard Cookery Writings devotes part of volume 4 to sushi. However other recipes in Delicacies from the Mountains and Seas cannot be taken at face value. Instant Water Shield, does not use any water shield, a type of freshwater seaweed. Instead, the recipe relies on yam buds as the main ingredient to give the appearance of water shield when fried. The recipe Pomegranates is for a steamed or fried sweet made from adzuki beans, dried rice, glutinous rice flour, wheat flour, and sugar. The author admits that the name Noodles of the Floating World (ukiyo udon) is a dish more commonly known simply as Egg Noodles, probably because the recipe calls for egg; however, Hakub shi prefers the more poetic name. Speaking of poetry, Teika’s Fish Cake is named after the Kamakura-period poet Fujiwara no Teika (1162–1241), whose credits include compiling the New Collection of Ancient and Modern Poems (Shin kokin sh

shi prefers the more poetic name. Speaking of poetry, Teika’s Fish Cake is named after the Kamakura-period poet Fujiwara no Teika (1162–1241), whose credits include compiling the New Collection of Ancient and Modern Poems (Shin kokin sh ) and commenting on the Heian-period classics Tosa Diary and Tale of Genji. In the Edo period, the poet’s name was also borrowed for a recipe for fish marinated in sake and salt called Teika’s Simmer (Teika ni).15 Although this well-known recipe does not appear in Delicacies from the Mountains and Seas, this text does includes the recipes K

) and commenting on the Heian-period classics Tosa Diary and Tale of Genji. In the Edo period, the poet’s name was also borrowed for a recipe for fish marinated in sake and salt called Teika’s Simmer (Teika ni).15 Although this well-known recipe does not appear in Delicacies from the Mountains and Seas, this text does includes the recipes K etsu Simmer, named for the artist Hon’ami K

etsu Simmer, named for the artist Hon’ami K etsu (1558–1637), and Riky

etsu (1558–1637), and Riky ’s Fish Sauce (hishio), an interesting tribute to the tea master, who was also honored with two other dishes in the sequel, Anthology of Special Delicacies.16 Practitioners of the tea ceremony in the Edo period venerated all three of these artists, which might provide a clue to Hakub

’s Fish Sauce (hishio), an interesting tribute to the tea master, who was also honored with two other dishes in the sequel, Anthology of Special Delicacies.16 Practitioners of the tea ceremony in the Edo period venerated all three of these artists, which might provide a clue to Hakub shi’s interest in the subject and the reason why he decided to honor these men with their own dishes.

shi’s interest in the subject and the reason why he decided to honor these men with their own dishes.

Many of the recipes in Delicacies from the Mountains and Seas are associated with places, consistent with the title of a volume that promises delicacies from the land and waterways around the country. In the previous list, Mikasa Miso and Kasuga Miso reference locations in Yamato province (modern Nara prefecture), while the Cold Dish from Sendai is supposedly from the castle town of that name in modern Miyagi prefecture in the northern part of the main island. Tosa Wheat Gluten points to a province in Shikoku, and the Southern Barbarian Simmer evokes Iberian foodways. Yet the connection between these places and dishes is not clear from the ingredients. The Cold Dish from Sendai is anything cut into three parts and served in water. The miso from Kasuga, which contains sake lees (kasu), might be a reference to Nara, famous both for Kasuga shrine and for its sake production, or it might simply be a pun on the name of the shrine, since Kasuga Miso can be read literally as “miso with kasu” (kasu ga miso).17 The recipe Southern Barbarian Simmer approximates an early version of tempura, fried fish served in a stock with green onions, but the recipe Mikasa Miso provides no apparent reason for the name. By Harada Nobuo’s count, 50 of the 460 total recipes from the two books have regional names. He is quick to point out that this does not mean the text is a regional cookbook, despite any knowledge of local specialties and their modes of preparation the author may have attempted to lay claim to.18 Indeed, Delicacies from the Mountains and Seas offers much more than that.

The names of regional foods are instead a type of word game, and perhaps we would find other geographic references—we would certainly discover more puns—if we could decipher all the author’s names for dishes. The names of several recipes in Delicacies from the Mountains and Seas are obtuse to the point that it is unclear they are actually foods—we have to read the ingredients to know what they are. Nine-two Stones, for example, is grilled marinated tofu. The name might derive from the fact that ishi’ishi was a poetic word for rice dumpling (dango), which the tofu in this dish resembled.19 But that does not explain the significance of nine-two, unless the phrase nine-two stones (kuni’ishi) is a pun for a word for gunpowder, also called 9-2-1 (kuni’ichi), after the proportions of the ingredients used to make it. Black Eyes in Light Snow refers to grated daikon on top of boiled sardines, which were called black eyes. Quiver Tofu (ebira d fu) might be a reference to the title of the Noh play Ebira, in which the lead actor breaks off a flower-laden plum branch and puts it in his quiver. As in the play, plum flowers figure prominently in the recipe.20 Dew Child is the name of a steamed dessert made from yam, wheat flour, salt, and sugar colored with gardenia. Solid Gold Soup consists of a miso stock with round slices of daikon and a type of trout that takes on a golden color in the springtime.21 The recipe Deep Thought Wheat Gluten is for pressed tofu mixed with wheat gluten that is first steamed, then simmered in soy sauce, and then covered with wasabi and miso. These names are indicative of the titles of other recipes in the volume, which include the physically impossible name Falling Frost (shimofuri), a recipe for ground fish served on chrysanthemum leaves that visually puns frost on a leaf, and a grilled rice cake sweet called Kannon Sutra (Kannon ky

fu) might be a reference to the title of the Noh play Ebira, in which the lead actor breaks off a flower-laden plum branch and puts it in his quiver. As in the play, plum flowers figure prominently in the recipe.20 Dew Child is the name of a steamed dessert made from yam, wheat flour, salt, and sugar colored with gardenia. Solid Gold Soup consists of a miso stock with round slices of daikon and a type of trout that takes on a golden color in the springtime.21 The recipe Deep Thought Wheat Gluten is for pressed tofu mixed with wheat gluten that is first steamed, then simmered in soy sauce, and then covered with wasabi and miso. These names are indicative of the titles of other recipes in the volume, which include the physically impossible name Falling Frost (shimofuri), a recipe for ground fish served on chrysanthemum leaves that visually puns frost on a leaf, and a grilled rice cake sweet called Kannon Sutra (Kannon ky ).22 It is more difficult to reconcile the names of recipes with the dishes in Delicacies from the Mountains and Seas than it is to prepare the dishes, because the recipes are not complicated, running just a few sentences each. For example, the entire recipe called Persimmon Pickles states, “Pickle whole persimmons in rice bran. Bitter persimmons are best.” The ingredients and method of preparation seem to be afterthoughts to the clever names.

).22 It is more difficult to reconcile the names of recipes with the dishes in Delicacies from the Mountains and Seas than it is to prepare the dishes, because the recipes are not complicated, running just a few sentences each. For example, the entire recipe called Persimmon Pickles states, “Pickle whole persimmons in rice bran. Bitter persimmons are best.” The ingredients and method of preparation seem to be afterthoughts to the clever names.

Imaginative names also feature prominently in the writings of a near contemporary to Hakub shi, the French cookbooks of Marie Antoine (Antonin) Carême (1784–1833), pointing to the fact that imaginative names are more than just a random collection of terms but constitute an exploration of the power of food to signify. In both works there is a similar disconnection between the ingredients and the title of the recipe. Carême named his dishes after famous people, as seen in his L’Art de la cuisine française published in five volumes in 1833–34. He honored great Frenchmen—and a few people of other nationalities—for their contributions to the arts, sciences, warfare, and literature. These heroes included Victor Hugo, Rossini, Molière, and Virgil, as well as Carême’s own employers and famous culinary writers such as Brillat-Savarin. Carême provided place-names for 112 of 358 sauces in part 4 of this book, a text that Priscilla Parkhurst Ferguson says “takes us on a tour of the French provinces.” She explains the frequent disjunction between the names and the contents of many of the dishes: “Whereas the names of sauces with regional or foreign variations often connect to the products associated with the region—Périgord raises visions of truffles, Provence brings in garlic and tomatoes, Normandy touts its cream and shellfish—just as often, and particularly for sauces à la parisienne or à la française, there is no relationship at all. In other words, the system confers the meaning, not the external referent.”23

shi, the French cookbooks of Marie Antoine (Antonin) Carême (1784–1833), pointing to the fact that imaginative names are more than just a random collection of terms but constitute an exploration of the power of food to signify. In both works there is a similar disconnection between the ingredients and the title of the recipe. Carême named his dishes after famous people, as seen in his L’Art de la cuisine française published in five volumes in 1833–34. He honored great Frenchmen—and a few people of other nationalities—for their contributions to the arts, sciences, warfare, and literature. These heroes included Victor Hugo, Rossini, Molière, and Virgil, as well as Carême’s own employers and famous culinary writers such as Brillat-Savarin. Carême provided place-names for 112 of 358 sauces in part 4 of this book, a text that Priscilla Parkhurst Ferguson says “takes us on a tour of the French provinces.” She explains the frequent disjunction between the names and the contents of many of the dishes: “Whereas the names of sauces with regional or foreign variations often connect to the products associated with the region—Périgord raises visions of truffles, Provence brings in garlic and tomatoes, Normandy touts its cream and shellfish—just as often, and particularly for sauces à la parisienne or à la française, there is no relationship at all. In other words, the system confers the meaning, not the external referent.”23

Hakub shi’s efforts in his writings likewise connected simple recipes for pickles, side dishes, and miso soups with larger cultural fields; and he did this by his choice of names for recipes to transmute ingredients like an ordinary fish into symbolic gold. Earlier works such as Tales of Cookery and Assembly of Standard Cookery Writings did not use terms as imagi native as Hakub

shi’s efforts in his writings likewise connected simple recipes for pickles, side dishes, and miso soups with larger cultural fields; and he did this by his choice of names for recipes to transmute ingredients like an ordinary fish into symbolic gold. Earlier works such as Tales of Cookery and Assembly of Standard Cookery Writings did not use terms as imagi native as Hakub shi’s when naming dishes. Aside from a few instances, all the recipes in these volumes are titled according to either their principle ingredient or their method of preparation.

shi’s when naming dishes. Aside from a few instances, all the recipes in these volumes are titled according to either their principle ingredient or their method of preparation.

Despite the idiosyncratic organization of his books, Hakub shi’s recipes and style proved influential on later cookbook writers, as evidenced by their inclusion of his dishes. For example, his recipe for Deep Thought Wheat Gluten, which debuted in Delicacies from the Mountains and Seas, also appeared in later culinary books, including Threading Together the Sages of Verse (Kasen no kumi’ito), published in 1748; Writings for Chinese Style Vegetarian Dishes (Fucha ry

shi’s recipes and style proved influential on later cookbook writers, as evidenced by their inclusion of his dishes. For example, his recipe for Deep Thought Wheat Gluten, which debuted in Delicacies from the Mountains and Seas, also appeared in later culinary books, including Threading Together the Sages of Verse (Kasen no kumi’ito), published in 1748; Writings for Chinese Style Vegetarian Dishes (Fucha ry rish

rish ), the first volume of Speedy Guide to Cooking (Ry

), the first volume of Speedy Guide to Cooking (Ry ri hayashinan), published in 1801; and Connoisseur [of Fashionable Edo Cuisine] ([Edo ry

ri hayashinan), published in 1801; and Connoisseur [of Fashionable Edo Cuisine] ([Edo ry ko] ry

ko] ry rits

rits ), published in 1822.24 The recipe Water Tofu in Delicacies from the Mountains and Seas is suspiciously similar to one found in One Hundred Tricks with Tofu (T

), published in 1822.24 The recipe Water Tofu in Delicacies from the Mountains and Seas is suspiciously similar to one found in One Hundred Tricks with Tofu (T fu hyakuchin), published thirty-four years later.25 Both of Hakub

fu hyakuchin), published thirty-four years later.25 Both of Hakub shi’s books were reprinted several times, which helps explain their influence and also speaks to their popularity.26

shi’s books were reprinted several times, which helps explain their influence and also speaks to their popularity.26

A MAN’S GUIDE TO SWEET NAMES

Hakub shi was not the first author of a culinary writing to give imaginative names to prepared items, including foods. Centuries before his time, producers and connoisseurs of swords, sake, ceramics, ink, and incense had given special appellations, called mei, to these objects to distinguish them as valuable or significant. In the case of foods, the practice of giving special names to sweets existed by the turn of the seventeenth century, but the last two decades of the seventeenth century witnessed a proliferation of these imaginative names, coinciding with the rise of the confectionery business.27 Sweet makers used a greater number of colors in this period than they once had, but their basic ingredients remained constant and consisted of refined sugar, rice flour, and adzuki bean paste.28 Size, shape, design motifs, and coloration could be used to create different sweets, but the name of the sweet was what truly set it apart from others and made it more appealing. On occasion, confectioners turned to their chief customers, tea masters, and aristocrats for suggestions. Kyoto sweet maker Toraya, which served as a purveyor to the court beginning with the reign of Emperor Goyosei (1586–1611), claimed that more than fifty of the names of its sweets came from the inspiration of emperors or members of the aristocracy.29

shi was not the first author of a culinary writing to give imaginative names to prepared items, including foods. Centuries before his time, producers and connoisseurs of swords, sake, ceramics, ink, and incense had given special appellations, called mei, to these objects to distinguish them as valuable or significant. In the case of foods, the practice of giving special names to sweets existed by the turn of the seventeenth century, but the last two decades of the seventeenth century witnessed a proliferation of these imaginative names, coinciding with the rise of the confectionery business.27 Sweet makers used a greater number of colors in this period than they once had, but their basic ingredients remained constant and consisted of refined sugar, rice flour, and adzuki bean paste.28 Size, shape, design motifs, and coloration could be used to create different sweets, but the name of the sweet was what truly set it apart from others and made it more appealing. On occasion, confectioners turned to their chief customers, tea masters, and aristocrats for suggestions. Kyoto sweet maker Toraya, which served as a purveyor to the court beginning with the reign of Emperor Goyosei (1586–1611), claimed that more than fifty of the names of its sweets came from the inspiration of emperors or members of the aristocracy.29

The profusion of lyrical names for confectionery is evident from the book Treasury for Men (Nanch h

h ki, also called Otoko ch

ki, also called Otoko ch h

h ki), authored by Namura J

ki), authored by Namura J haku (died after 1694) and first published in 1693 as a sequel to his guide for women, Treasury for Women (Onna ch

haku (died after 1694) and first published in 1693 as a sequel to his guide for women, Treasury for Women (Onna ch h

h ki), published a year earlier. This work was intended to provide commoners with essential, mundane know-how and included descriptions of fashionable confectionery. Treasury for Men lists the names of 250 sweets (205 steamed mushi gashi and 45 dry higashi sweets) and provides simple notations about their ingredients and method of preparation so that they can be readily identified when encountered. Namura probably compiled this information from one or more sample books created by confectioners to show their customers what they could order (see plate 8).30 The list of sweets in Treasury for Men begins by providing the names for five sweets with long pedigrees in Japan—manj

ki), published a year earlier. This work was intended to provide commoners with essential, mundane know-how and included descriptions of fashionable confectionery. Treasury for Men lists the names of 250 sweets (205 steamed mushi gashi and 45 dry higashi sweets) and provides simple notations about their ingredients and method of preparation so that they can be readily identified when encountered. Namura probably compiled this information from one or more sample books created by confectioners to show their customers what they could order (see plate 8).30 The list of sweets in Treasury for Men begins by providing the names for five sweets with long pedigrees in Japan—manj , y

, y kan, uir

kan, uir mochi, gy

mochi, gy hi, suhama. All of these except the last one—which is made from malt, ground soybeans, and sugar shaped into a “wave beaten shore” (suhama)—we have encountered in a previous chapter. The text then provides twenty-four illustrations of sweets with brief descriptions of each. In the Treasury for Men, so-called Whale Meat Rice Cake (kujira mochi) has a dark top made from y

hi, suhama. All of these except the last one—which is made from malt, ground soybeans, and sugar shaped into a “wave beaten shore” (suhama)—we have encountered in a previous chapter. The text then provides twenty-four illustrations of sweets with brief descriptions of each. In the Treasury for Men, so-called Whale Meat Rice Cake (kujira mochi) has a dark top made from y kan and a white bottom made from a rice flour base (konemono); the illustration shows a wave pattern imita tive of whale flesh. The next sweet, Plover on the Shore (hama chidori), features a square dividing a top triangle of yellow rice cake with a thin line of lumpy bean paste (azuki tsubo) from a bottom triangle of white rice cake. This zigzag pattern indicates a plover walking back and forth across a beach. More than a simple bird, the plover gave its name to a variety of objects in the tea ceremony, and it was an indirect reference to the “Suma” chapter in the Tale of Genji, where the exiled protagonist is kept awake by the bird’s cries.31 The final sweet, Raft Rice Cake (ikada mochi), is composed of four sections, white, yellow, black, and red, giving the impression of tiny rafts suggested by slices of chestnuts floating down this multihued river.

kan and a white bottom made from a rice flour base (konemono); the illustration shows a wave pattern imita tive of whale flesh. The next sweet, Plover on the Shore (hama chidori), features a square dividing a top triangle of yellow rice cake with a thin line of lumpy bean paste (azuki tsubo) from a bottom triangle of white rice cake. This zigzag pattern indicates a plover walking back and forth across a beach. More than a simple bird, the plover gave its name to a variety of objects in the tea ceremony, and it was an indirect reference to the “Suma” chapter in the Tale of Genji, where the exiled protagonist is kept awake by the bird’s cries.31 The final sweet, Raft Rice Cake (ikada mochi), is composed of four sections, white, yellow, black, and red, giving the impression of tiny rafts suggested by slices of chestnuts floating down this multihued river.

As in these examples and the remainder of the twenty-four illustrated sweets, the connection between the appearance of the sweet and the name is discernable. Moneybag Rice Cake (shakin mochi) looks like a pouch filled with coins, but it is in fact stuffed with bean paste and cinnamon. Whirlpool (uzumaki) is made from a thin dough spread with bean paste, then rolled up and cut into sections to reveal a spiral. Cherry Blossom Rice Cake is a sweet in the shape of the flower, and the notation indicates that it too is filled with bean paste.

Yet more imagination is required for the sweets that follow, since only their names and very simple notations about their composition are provided. Many of these sweets’ names have seasonal references, as exemplified by Autumn Field (aki no no), Spring Mist (haru kasumi), and Autumn Mountain Rice Cake (akiyama mochi). Meteorological references abound, with Misty-Moonlit-Night Rice Cake (oboroyo mochi) and Autumn Mist (akikasumi), as do topographic ones such as Mountain Trail Cake (yamaji mochi) and Evening Tide ([namikawari). Objects from daily life appear: Perfumed-Sleeves Rice Cake (sode no ka mochi), Card Game Cake (karuta mochi), and Memo-Paper Rice Cake (koshikishi mochi). These share room with more fantastic names: Twilight Cake (y kure mochi), Bumper Crop Cake (h

kure mochi), Bumper Crop Cake (h ry

ry mochi), Jewel-Well Cake (tamai mochi), and Thousand-Year-Reign Cake (chone mochi). The sweets named Traveling Companion Rice Cake (michitsure mochi), Cart of Flowers (hanaguruma), and Pajamas (sayo koromo) provoke contemplation or a smile.32 Other names of sweets in Treasury for Men make references to settings from the tenth-century book of poetry Collection of Ancient and Modern Poems (Kokinsh

mochi), Jewel-Well Cake (tamai mochi), and Thousand-Year-Reign Cake (chone mochi). The sweets named Traveling Companion Rice Cake (michitsure mochi), Cart of Flowers (hanaguruma), and Pajamas (sayo koromo) provoke contemplation or a smile.32 Other names of sweets in Treasury for Men make references to settings from the tenth-century book of poetry Collection of Ancient and Modern Poems (Kokinsh ) and borrow terminology from the arts of incense appreciation and the tea ceremony, evidencing the level of knowledge required to decode and appreciate them.33

) and borrow terminology from the arts of incense appreciation and the tea ceremony, evidencing the level of knowledge required to decode and appreciate them.33

In this light, the names of sweets, like the titles of the recipes in Delicacies from the Mountains and Seas and Anthology of Special Delicacies, confer meaning on what would otherwise be just a colorful lump of raw ingredients. The names of sweets are, in the words of the historian of Japanese confectionery Nakayama Keiko, “edible seasonal words” (taberu kigo), referencing the set expressions used in letter writing to draw attention to the passing of time. These have been transformed into a way of enjoying confectionery that precedes and endures after the taste itself has disappeared.34 One modern confectioner, owner of the prominent confectionery business Suetomi in Kyoto, has commented that the meaning of a sweet stems chiefly from its shape and the name.35 Indeed, several sweets sold today use the same design and ingredients and have a similar appearance, but employ different names.36 Consequently, far from being a sign of the decline of cuisine, the profusion of multiple poetic names attests to the development of the art of confectionery, as it did for Japanese cuisine in the Edo period.

THE BACKSTORY TO DAIKON

The fascination with different names for dishes composed of similar ingredients found fullest expression in the Edo period in the so-called hundred tricks series of recipe books, which was inaugurated by the publication of One Hundred Tricks with Tofu in 1782. The titles of these different texts advertised a hundred ways to cook and serve tofu, eggs, daikon, whale, rice dishes, conger eel, and devil’s tongue.

An author who wrote under the name Kidod (n.d.) dominated this genre of writings. Little is known about this mysterious author. Kidod

(n.d.) dominated this genre of writings. Little is known about this mysterious author. Kidod may have worked as a professional restaurant chef in Kyoto, where all his books were published. The preface to one of his writings, Secret Digest of Exceptional Radish Dishes throughout the Land (Shokoku meisan daikon ry

may have worked as a professional restaurant chef in Kyoto, where all his books were published. The preface to one of his writings, Secret Digest of Exceptional Radish Dishes throughout the Land (Shokoku meisan daikon ry ri hidensh

ri hidensh ), refers to him as a cook (ry

), refers to him as a cook (ry rinin), and the same text invites readers to visit the author if they have any questions about food preparation. If Kidod

rinin), and the same text invites readers to visit the author if they have any questions about food preparation. If Kidod was serious about this invitation, this implies that readers would know how to track him down.37 Judging from his publications, which are the only record we have for him, he was certainly prolific and imaginative. As the following table indicates, Kidod

was serious about this invitation, this implies that readers would know how to track him down.37 Judging from his publications, which are the only record we have for him, he was certainly prolific and imaginative. As the following table indicates, Kidod wrote six of the sixteen hundred-tricks texts, far more than any other author. This is all the more remarkable for the fact that five of his books appeared in print in the same year.

wrote six of the sixteen hundred-tricks texts, far more than any other author. This is all the more remarkable for the fact that five of his books appeared in print in the same year.

One example from this list can provide an overview of this genre of culinary book. Like the other works, New Select Culinary Secret Treasury of Citron Delicacies (Shinch ry

ry ri y

ri y chin himitsubako) contains multiple recipes for its principle ingredient. These include Citron-Flavored Rice, Citron-Flavored Bean Cakes (manj

chin himitsubako) contains multiple recipes for its principle ingredient. These include Citron-Flavored Rice, Citron-Flavored Bean Cakes (manj ), Citron Preserved in Sugar, Citron Tempura, Citron Tofu, Citron Dengaku, and Citron Pickles to name a few of its forty dishes. The book also provides three methods for preserving citrons for future use.38

), Citron Preserved in Sugar, Citron Tempura, Citron Tofu, Citron Dengaku, and Citron Pickles to name a few of its forty dishes. The book also provides three methods for preserving citrons for future use.38

TABLE 6 “HUNDRED TRICKS” TEXTS

Title |

Author |

Date of Publication |

One Hundred Tricks with Tofu (T fu hyakuchin) fu hyakuchin) |

Ka Hitsujun (Sotani Gakusen) |

1782 |

Sequel to a Hundred Tricks with Tofu (T fu hyakuchin zokuhen) fu hyakuchin zokuhen) |

Ka Hitsujin |

1783 |

A Hundred More Tricks with Tofu (T fu hyakuchin yoroku) fu hyakuchin yoroku) |

Unknown |

1784 |

A Collection of Menus of Ten Thousand Treasures (Manp ry ry ri kondatesh ri kondatesh ) ) |

Kidod |

1785 |

Complete Secret Treasury of Daikon Dishes (Daikon isshiki ry ri himitsubako) ri himitsubako) |

Kidod |

1785 |

New Select Culinary Secret Treasury of Citron Delicacies (Shinch ry ry ri y ri y chin himitsubako) chin himitsubako) |

Kidod |

1785 |

A Secret Box of Ten Thousand Culinary Treasures, vol. 1 (Manp ry ry ri himitsubako [zenpen]) ri himitsubako [zenpen]) |

Kidod |

1785 |

Secret Digest of Exceptional Radish Dishes throughout the Land (Shokoku meisan daikon ry ri hidensh ri hidensh ) ) |

Kidod |

1785 |

Secret Treasury of One Hundred Sea Bream Dishes (Tai hyakuchin ry ri himitsubako) ri himitsubako) |

Kidod |

1785 |

One Hundred Tricks with Sweet Potato (Imo hyakuchin) |

Master Chinkor |

1789 |

A Hundred Tricks with Conger Eel (Kaiman hyakuchin) |

Unknown |

1795 |

A Secret Box of Ten Thousand Culinary Treasures, vol. 2 (Manp ry ry ri himitsubako [nihen]) ri himitsubako [nihen]) |

Kidod |

1800 |

Great Rice Dishes Categorized (Meihan burui) |

Sugino Gon’emon |

1802 |

Delicacies with Whale Meat (Geiniku ch mih mih ) ) |

Unknown |

1832 |

Crafting Eggs, the Water Dish Cooking Method (Mizu ry ri yakikata tamago saiku) ri yakikata tamago saiku) |

Unknown |

1846 |

One Hundred Tricks with Devil’s Tongue (Kon’yaku hyakuchin) |

Shi’nyaku Nobuhito* |

1846 |

* Shi’nyaku Nobuhito is an obvious pen name. Literally, it means a person who tells about his love for kon’yaku.

Kidod ’s work on daikon, Secret Digest of Exceptional Radish Dishes throughout the Land, stands apart from the other hundred-tricks texts that are simply lists of different recipes for a single ingredient. The first of two volumes offers recipes for daikon in the manner typical of hundred-tricks texts. However, the second volume contains recipes and daikon ephemera, as Kidod

’s work on daikon, Secret Digest of Exceptional Radish Dishes throughout the Land, stands apart from the other hundred-tricks texts that are simply lists of different recipes for a single ingredient. The first of two volumes offers recipes for daikon in the manner typical of hundred-tricks texts. However, the second volume contains recipes and daikon ephemera, as Kidod describes in the preface: “This volume sets down the history of famous simmered dishes and pickles from various provinces. Part of the second half of the volume describes through the use of simple illustrations how to make varieties of artificial flowers and other traditional ornaments.”39 This part is titled “Secret Transmission of Preparing Cuttings from a Daikon with a Knife” (Daikon h

describes in the preface: “This volume sets down the history of famous simmered dishes and pickles from various provinces. Part of the second half of the volume describes through the use of simple illustrations how to make varieties of artificial flowers and other traditional ornaments.”39 This part is titled “Secret Transmission of Preparing Cuttings from a Daikon with a Knife” (Daikon h ch

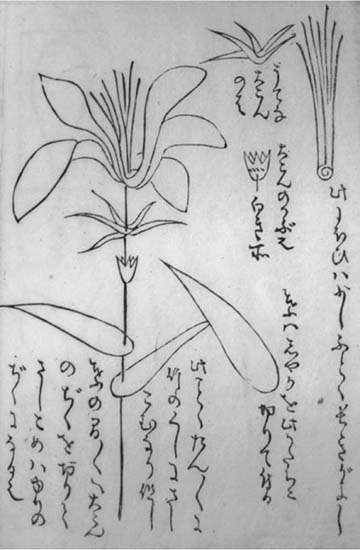

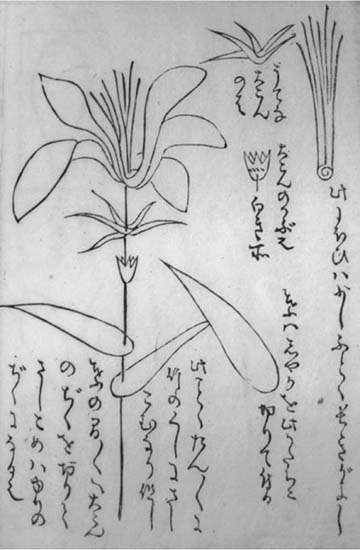

ch mono kirikata no hiden), and it offers illustrations and gives directions for carving daikon into delicate plum and camellia flowers, cherry blossoms, irises, peonies, pinks (nadeshiko), lilies, and other flora (see figure 10). The instructions culminate with tips for turning a daikon into a chain of circular slices artfully joined together.

mono kirikata no hiden), and it offers illustrations and gives directions for carving daikon into delicate plum and camellia flowers, cherry blossoms, irises, peonies, pinks (nadeshiko), lilies, and other flora (see figure 10). The instructions culminate with tips for turning a daikon into a chain of circular slices artfully joined together.

Kidod ’s preface deserves attention for his comments in which he sought to record the history of various daikon dishes. His words are reminiscent of Delicacies from the Mountains and Seas—or perhaps the ancient Chinese text Guideways through Mountains and Streams that inspired it—because he links unusual dishes with a geographical context. He provides readers with a virtual culinary tour of the country, but one focused on daikon, as opposed to a bestiary listing many different rare creatures. His chosen quarry is the most humble of ingredients, one that was readily available to the point of being mundane. However, the information Kidod

’s preface deserves attention for his comments in which he sought to record the history of various daikon dishes. His words are reminiscent of Delicacies from the Mountains and Seas—or perhaps the ancient Chinese text Guideways through Mountains and Streams that inspired it—because he links unusual dishes with a geographical context. He provides readers with a virtual culinary tour of the country, but one focused on daikon, as opposed to a bestiary listing many different rare creatures. His chosen quarry is the most humble of ingredients, one that was readily available to the point of being mundane. However, the information Kidod conveys about the daikon turns it from an ordinary to an almost magical root vegetable.

conveys about the daikon turns it from an ordinary to an almost magical root vegetable.

The first recipe, Quick Daikon Simmer (daikon hayani no tsukurikata), sets the pattern for the author’s connection between food preparation and radish lore.

In this passage Kidod names several dishes that will appear later in the text, before launching into the recipe for the quick simmered dish, which itself is rather simple: slices of daikon fried in sesame oil and then simmered in water. Without the elaborate preface, the recipe would seem ordinary, even with the additions for variations that call for adding soy sauce and miso. His preface is clearly a setup for the great matters that lie ahead, which promise to be encyclopedic in their salutation to a single vegetable, with a few asides about turnips.

names several dishes that will appear later in the text, before launching into the recipe for the quick simmered dish, which itself is rather simple: slices of daikon fried in sesame oil and then simmered in water. Without the elaborate preface, the recipe would seem ordinary, even with the additions for variations that call for adding soy sauce and miso. His preface is clearly a setup for the great matters that lie ahead, which promise to be encyclopedic in their salutation to a single vegetable, with a few asides about turnips.

FIGURE 10. Directions for cutting a daikon to look like a flower, from Secret Digest of Exceptional Radish Dishes throughout the Land (Shokoku meisan daikon ry ri hidensh

ri hidensh ). Courtesy of the Ajinomoto Foundation for Dietary Culture.

). Courtesy of the Ajinomoto Foundation for Dietary Culture.

How does the author deliver on this enormous task of telling readers everything they need to know about daikon? Several of his recipes are, like the dishes in Delicacies from the Mountains and Seas, poetically named, including Brocade Daikon (nishiki daikon) and Daikon Light Snow Soup, which makes use of ground daikon that resembles falling snow when served swirling in a soup. However, most of the names of the recipes and their methods of preparation invoke specific locations, villages, temples, cities, and provinces. Twenty-two of the forty-four recipes in the book reference one or more locations in Japan, which the author claims are either famous for growing daikon or for a method of preparing them. In the recipe Quick Simmer with Dried Daikon or Dried Turnips (hoshi daikon, hoshi kabura hayani no shikata), only a small proportion of the text is dedicated to actual directions for preparing the dish. The remainder spotlights places in Japan famous for dried daikon, including Miyashige daikon in Owari province, Nishij in Iyo province, and Iinohara in Harima province, as well as locations in Kyoto,

in Iyo province, and Iinohara in Harima province, as well as locations in Kyoto,  mi, Tosa, Nagaoka, and Osaka. Other recipes include a place-name as part of the title, such as Famous Katori Shrine in Shimousa Simmered Daikon (Shimousa meibutsu katori ni daikon), Tango’s Famous Daikon with Steamed Millet (Tango meibutsu awamushi daikon), and Chikuzen Malted Rice Simmered Daikon (Chikuzen k

mi, Tosa, Nagaoka, and Osaka. Other recipes include a place-name as part of the title, such as Famous Katori Shrine in Shimousa Simmered Daikon (Shimousa meibutsu katori ni daikon), Tango’s Famous Daikon with Steamed Millet (Tango meibutsu awamushi daikon), and Chikuzen Malted Rice Simmered Daikon (Chikuzen k jini daikon). Kidod

jini daikon). Kidod ties all three of these dishes not only to places but also to particular religious institutions in those places, adding another layer of meaning to his commentary. The dish from Tango, according to the author, is “served in religious ceremonies in a place called Yosa,” while the Chikuzen dish originates from a religious institution there called Kint

ties all three of these dishes not only to places but also to particular religious institutions in those places, adding another layer of meaning to his commentary. The dish from Tango, according to the author, is “served in religious ceremonies in a place called Yosa,” while the Chikuzen dish originates from a religious institution there called Kint b

b . Other dishes are named after famous people: tea master Sen no Riky

. Other dishes are named after famous people: tea master Sen no Riky ’s name appears in two titles, and the Confucian scholar Hayashi Razan’s Buddhist name appears in one title.41

’s name appears in two titles, and the Confucian scholar Hayashi Razan’s Buddhist name appears in one title.41

The religious dimension of daikon appears to have a particular fascination for the author. Kidod explains that the recipe Daikon Grand Shrine Simmer is a specialty of Izumo and is prepared in homes there in the eleventh month as a prayer to the deities for the birth of a child. He includes the story about how all the deities in Japan congregate in Izumo in the preceding month at the Grand Shrine, named in his recipe.42 His recipe Daikon Salad (daikon namasu) headlines the second volume, accompanied by a long story about the origin of this dish, one he traced back to the period of the ancient Emperor Ch

explains that the recipe Daikon Grand Shrine Simmer is a specialty of Izumo and is prepared in homes there in the eleventh month as a prayer to the deities for the birth of a child. He includes the story about how all the deities in Japan congregate in Izumo in the preceding month at the Grand Shrine, named in his recipe.42 His recipe Daikon Salad (daikon namasu) headlines the second volume, accompanied by a long story about the origin of this dish, one he traced back to the period of the ancient Emperor Ch ai, who made an offering of daikon when he moved the site of his court. In the same passage, Kidod

ai, who made an offering of daikon when he moved the site of his court. In the same passage, Kidod explains the spiritual cosmology of daikon salad.

explains the spiritual cosmology of daikon salad.

The tastes Kidod described for salad were only one dimension of a dish that was for him a microcosm of the universe and the forces within it.

described for salad were only one dimension of a dish that was for him a microcosm of the universe and the forces within it.

In addition to discussing the religious symbolism of dishes made with daikon and where the best daikon could be found in Japan, Kidod includes other daikon facts. We read that daikon can be used to tell directions: in a field the thickest roots of a daikon always grow on the southern side. Daikon was first added to the traditional New Year’s “simmered dish” (oz

includes other daikon facts. We read that daikon can be used to tell directions: in a field the thickest roots of a daikon always grow on the southern side. Daikon was first added to the traditional New Year’s “simmered dish” (oz ni) in the time of Prince Sh

ni) in the time of Prince Sh toku (574–622). And daikon is offered to the deities at Sumiyoshi shrine in Sakai and at Shimogamo shrine in Kyoto for the Aoi festival. Daikon pickles “are the most important treasure in a household” and will bring good luck and drive away plagues and disasters. A medicine can be made from daikon in the tradition of the great physician Got

toku (574–622). And daikon is offered to the deities at Sumiyoshi shrine in Sakai and at Shimogamo shrine in Kyoto for the Aoi festival. Daikon pickles “are the most important treasure in a household” and will bring good luck and drive away plagues and disasters. A medicine can be made from daikon in the tradition of the great physician Got Konzan (d. 1733) that will cure someone who needs to urinate frequently at night. Taking daikon will induce vomiting in someone sickened from eating spoiled tofu or choking on a piece of food. Finally, the dried leaves of daikon, if picked three to four days after the daikon has been dug from the earth, are a cure for gonorrhea.44

Konzan (d. 1733) that will cure someone who needs to urinate frequently at night. Taking daikon will induce vomiting in someone sickened from eating spoiled tofu or choking on a piece of food. Finally, the dried leaves of daikon, if picked three to four days after the daikon has been dug from the earth, are a cure for gonorrhea.44

Even if readers do not attempt to cut daikon into delicate flowers, which would require considerable dexterity with a knife, or even if they do not simmer daikon following one of Kidod ’s recipes, Secret Digest of Exceptional Radish Dishes throughout the Land can be enjoyed purely for its daikon trivia, which it contains in full measure. Accordingly, the text might be retitled One Hundred (or More) Facts about Daikon, since the massive amount of information it presents overshadows the recipes for preparing daikon, which are relatively few in number and meager in description.

’s recipes, Secret Digest of Exceptional Radish Dishes throughout the Land can be enjoyed purely for its daikon trivia, which it contains in full measure. Accordingly, the text might be retitled One Hundred (or More) Facts about Daikon, since the massive amount of information it presents overshadows the recipes for preparing daikon, which are relatively few in number and meager in description.

Clearly it is the backstory to daikon that make the humble root vegetable interesting from several intellectual standpoints, and Kidod successfully locates it in the landscape, religious practice, history, and medicine. Rather than present a hundred ways to prepare one ingredient, he has shown how one ingredient can vary in a hundred ways according to the intellectual approaches taken to it. A geographic view locates the daikon according to its terroir, famous modes of preparation, and local culture. Daikon can also be considered for its many uses in religious ceremonies, and it has medicinal properties. What Kidod

successfully locates it in the landscape, religious practice, history, and medicine. Rather than present a hundred ways to prepare one ingredient, he has shown how one ingredient can vary in a hundred ways according to the intellectual approaches taken to it. A geographic view locates the daikon according to its terroir, famous modes of preparation, and local culture. Daikon can also be considered for its many uses in religious ceremonies, and it has medicinal properties. What Kidod offered his readers was an intellectual appreciation of a vegetable anyone could afford and most people ate daily.

offered his readers was an intellectual appreciation of a vegetable anyone could afford and most people ate daily.

ri sankaiky

ri sankaiky , 1750) and Anthology of Special Delicacies (Ry

, 1750) and Anthology of Special Delicacies (Ry ri chinmish

ri chinmish , 1764). He also includes the so-called hundred tricks (hyakuchin) texts, a series of books published beginning in the 1780s that featured a hundred recipes for a single ingredient, albeit he finds them more technical than other texts written for amusement. In regard to all these works, Harada says that, “at this point, cuisine [ry

, 1764). He also includes the so-called hundred tricks (hyakuchin) texts, a series of books published beginning in the 1780s that featured a hundred recipes for a single ingredient, albeit he finds them more technical than other texts written for amusement. In regard to all these works, Harada says that, “at this point, cuisine [ry ri] transcended a reliance on gustatory enjoyment. It became possible to enjoy cuisine as an abstraction, seeking satisfaction in information that appealed to the visual senses.”1 While noting the significance of this development, Harada nonetheless takes it as a sign that Japan’s culinary culture has entered a period of decline. “The culinary culture . . . was characterized by an emphasis on ‘playful’ elements; thus, it lacked real substance and merely proceeded along the same line of ever more refined, purely secondary and inconsequential aspects of food preparation.”2 If we limit the definition of cuisine (ry

ri] transcended a reliance on gustatory enjoyment. It became possible to enjoy cuisine as an abstraction, seeking satisfaction in information that appealed to the visual senses.”1 While noting the significance of this development, Harada nonetheless takes it as a sign that Japan’s culinary culture has entered a period of decline. “The culinary culture . . . was characterized by an emphasis on ‘playful’ elements; thus, it lacked real substance and merely proceeded along the same line of ever more refined, purely secondary and inconsequential aspects of food preparation.”2 If we limit the definition of cuisine (ry ri) to cooking techniques as Harada does here, then an intellectual appreciation of food may be inconsequential. However, the story of Japanese cuisine examined in this book has shown that contemplating or fantasizing with food is central to cuisine. To recall Priscilla Parkhurst Ferguson’s pithy definition, cuisine is “the cultural code that enables societies to think with and about the food they consume.”3 Consequently, rather than signaling a decline in culinary culture, the recipe books of the late Edo period that Harada criticizes represent a blossoming of popular thinking about food as they reveal new ways to enjoy food intellectually. This flowering of inter est in cuisine coincided with a boom in cookbook publishing that began in the 1770s and peaked around 1800, but continued strong until the 1850s, shortly before the end of the Tokugawa period.4

ri) to cooking techniques as Harada does here, then an intellectual appreciation of food may be inconsequential. However, the story of Japanese cuisine examined in this book has shown that contemplating or fantasizing with food is central to cuisine. To recall Priscilla Parkhurst Ferguson’s pithy definition, cuisine is “the cultural code that enables societies to think with and about the food they consume.”3 Consequently, rather than signaling a decline in culinary culture, the recipe books of the late Edo period that Harada criticizes represent a blossoming of popular thinking about food as they reveal new ways to enjoy food intellectually. This flowering of inter est in cuisine coincided with a boom in cookbook publishing that began in the 1770s and peaked around 1800, but continued strong until the 1850s, shortly before the end of the Tokugawa period.4 ry

ry ’s Fish Sauce (hishio), an interesting tribute to the tea master, who was also honored with two other dishes in the sequel, Anthology of Special Delicacies.

’s Fish Sauce (hishio), an interesting tribute to the tea master, who was also honored with two other dishes in the sequel, Anthology of Special Delicacies.

mi, Tosa, Nagaoka, and Osaka. Other recipes include a place-name as part of the title, such as Famous Katori Shrine in Shimousa Simmered Daikon (Shimousa meibutsu katori ni daikon), Tango’s Famous Daikon with Steamed Millet (Tango meibutsu awamushi daikon), and Chikuzen Malted Rice Simmered Daikon (Chikuzen k

mi, Tosa, Nagaoka, and Osaka. Other recipes include a place-name as part of the title, such as Famous Katori Shrine in Shimousa Simmered Daikon (Shimousa meibutsu katori ni daikon), Tango’s Famous Daikon with Steamed Millet (Tango meibutsu awamushi daikon), and Chikuzen Malted Rice Simmered Daikon (Chikuzen k