In 1991, you could walk into any McDonald's in the United States, hand the teenager behind the counter a single dollar bill, and take home a double cheeseburger or a chicken sandwich. Back then, a gallon of gas cost an average of $1.14 in the United States (today it's $3.83), and the federal hourly minimum wage was $4.25 (today it's $7.25). In fact, the purchasing power of a dollar was 70 percent higher two decades ago. In the words of the immortal Yankee Yogi Berra, “A nickel ain't worth a dime anymore.”

But here's a surprise. Walk into a McDonald's today and hand one thin dollar to the teenaged descendant of your former cashier. Unless you no longer eat such things, you can still leave with a double cheeseburger or a chicken sandwich. In fact, animal food prices in the United States have been remarkably resistant to the forces of inflation over the past century, falling across the board (in inflation-adjusted terms) while most other consumer goods continue to rise in price.

In the book's second half, I explore why the retail prices of meat and dairy are so low and what these low prices really mean for consumers. The common, knee-jerk reaction to lower prices is “Great! I can buy more!” But in this case, low prices are both cause and effect of a microeconomic system out of whack. In fact, by keeping the system in a perpetual state of disequilibrium, or market failure, the forces of meatonomics create problems that affect almost everyone. For the skeptical, there is a mounting pile of evidence that artificially low prices actually hurt, rather than help, consumers. This chapter introduces some of the hidden costs of meat and dairy production and explores one particularly controversial item: subsidies.

Meat and dairy are cheap. From 1980 to 2008, the inflation-adjusted prices of ground beef and cheddar cheese fell by 53 and 27 percent, respectively.1 During roughly the same period, the inflation-adjusted prices of fruits and vegetables rose by 46 and 41 percent, respectively.2 The result is that in contrast to their relative prices three decades ago, today a dollar buys three times the ground beef compared to vegetables that it once did.

The main reason for the steep drop in meat and dairy prices is that producers have made animal agriculture practices vastly more efficient. Back in the day, animal farming was heavily land intensive. But the modern shift to high-density, hyper-confinement methods has greatly reduced the need for wide open spaces. Automated processes have reduced labor costs. Consolidation and increased output volumes allow producers to enjoy economies of scale. And animals are now bred to grow larger and reach slaughter weight sooner.

The efficiency gains are noteworthy. Per-hen egg production has doubled in the last century.3 Per-cow dairy production has tripled.4 And the average weight of broiler chickens has almost tripled, while the birds' growth rate has more than doubled.5 On the surface, it looks like innovation is doing what it should, which is to reduce prices. But a closer look at the economic costs of animal foods suggests something more complicated is happening.

If I pay a garbage service to collect my trash, my disposal costs are internalized. Appropriately, because I generated the trash, I pay the collection costs. But if I drive over to the local park at midnight and dump my trash there, I've imposed my disposal costs on others. Such “externalized costs” are those expenses related to producing or consuming a good that are not reflected in the good's price and are instead passed on to third parties. This concept is critical to understanding the economics of animal food production.

As taxpayers, we routinely pick up the check for externalities that everyday transactions generate. Take cigarettes. Because of the costly health problems associated with smoking and exposure to second-hand smoke, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimate that each pack of cigarettes sold imposes externalized health care costs of $10.47 on Americans.6 But even with cigarette taxes as high as $5.85 per pack in some areas, governments are far from recovering all of the externalized costs. Cigarette manufacturers, of course, pay almost none of these costs. The result is that the additional price of smoking is borne by many who don't smoke, including taxpayers and those who pay health insurance premiums. In other words, even if you don't smoke, you're writing checks to cover the doctor bills of those who do.

Calculating external costs can be controversial. To summon a well-worn cliché, the devil is in the details. Free market advocates downplay the extent and value of externalities, while those who favor market regulation find costly externalities wherever they turn. For example, imagine that the construction of an oil pipeline harms caribou herds in remote areas. Some might argue that as a non-market animal—that is, a species we don't normally use for food, clothing, or entertainment—these remote herds have no economic value and their decline generates no external costs. Others would say that the amount that animal-friendly humans are willing to pay to protect the caribou is an external cost of building the pipeline.

In the case of animal foods, their low retail prices obscure a significant, measurable set of external costs that make the real costs to society much higher. Many of these expenses, such as taxpayer subsidies, health care costs, and environmental costs, have been extensively researched and documented. When these documented tallies are considered, the true price of a Dollar Menu double cheeseburger turns out to be a lot higher than a buck. Moreover, there is little comfort in the superficially pleasing idea that economic conditions keep prices low for consumers. Anything that seems too good to be true probably is too good to be true. In fact, low animal food prices are largely illusory because these goods' true costs are shifted to consumers in roundabout ways. Ultimately, the numbers show that the big winners from these heavy external costs are a handful of animal food industry fat cats and the few companies who provide them with supplies like feed, drugs, and equipment.

It's common—and usually perfectly legal—for corporations to externalize as much of their costs as possible. And of course, animal agribusiness isn't the only American industry to impose billions in hidden costs on consumers and taxpayers. But this sector is far and away leading the pack in the category, offloading more costs than any other.

Consider electricity generation. That industry is known to impose tremendous external costs on society, mainly in the form of health problems and ecological damage resulting from burning coal and oil. A 2009 study by the National Research Council summed up the quantifiable, externalized costs of US electricity generation and found they total $63 billion yearly (in 2005 dollars).7 That's a sizable figure, but even adjusting it for inflation ($75 billion), it's less than one-fifth of animal foods' measurable external costs.

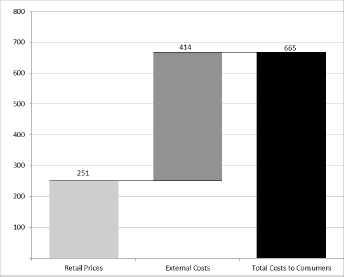

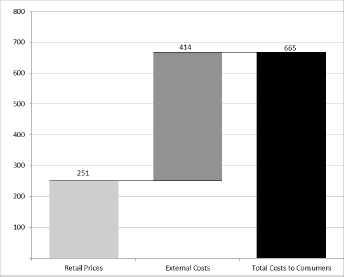

One way to estimate the total cost to consumers of animal foods is to add external costs to retail prices, since generally, Americans who consume animal foods will incur both the retail prices and the externalized costs.8 The industry's total annual retail sales are about $251 billion.9 But that's chump change compared to the total external costs of animal food production, which are shown below to be $414 billion.10 As Chart 5.1 shows, adding external costs to retail sales yields total consumer costs of about $665 billion.11 From this perspective, each $1 in retail sales of animal foods generates about $1.70 in external costs. The true cost of a $5 carton of organic eggs is roughly $13. A $10 steak actually costs about $27.

Here's another way to think about the ratio of prices (what we pay at the cash register) to costs (all relevant expenses—whether paid or not). Over the past century, the large gains in production efficiency that accompanied the rise of industrial agriculture helped drive the retail prices of animal foods lower. The growth rate of chickens doubled while the price per pound fell. However, as Milton Friedman famously observed, “There's no such thing as a free lunch.” In fact, the same gains in efficiency that reduce prices also increase externalized costs. Chickens develop faster in part because they're fed growth-promoting antibiotics, but those drugs cause costly antibiotic resistance when they end up in our food and our waterways, making it that much harder for us to fight off a slew of sicknesses—and leading to more time in the doctor's office. Animals packed in factories can be raised more cheaply than those raised on pasture, but separating animals from land means their waste must be collected and stored. Some of this waste ends up in our water supply and generates serious clean-up costs. Like a new car promotion that offers twelve months without payments, the price of factory farming has been deferred or ignored—but by no means eliminated.

CHART 5.1 Total Costs to Consumers of Animal Foods (in billions of dollars)

If your diet tends toward the omnivorous, you might feel a sense of satisfaction that the prices you pay for meat and dairy are lower than they would be if external costs were imposed at the cash register. On the other hand, if you don't eat animal foods, you might feel relief that at least you're not participating in the system. But in either case, your wallet or pocketbook is going to feel the hit. That's because, like it or not, even though we don't pay them at the cash register, we all do incur the costs of animal food production in one way or another. For example, even if you're lucky enough never to develop cancer, diabetes, or heart disease, you'll still help finance the treatment of those who do (unfortunately, many cases of these three diseases are attributable to consumption of meat, fish, eggs, and dairy).

Regardless of your eating habits, there's no way to avoid this steep burden. Don't eat fish? It doesn't matter—you'll still sustain your share of the expenses of overfishing, algal blooms, and other problems associated with fishing and fish farming. Don't eat meat or dairy? Vegetarians and vegans experience the externalized costs of animal foods at the same rate as the rest of society. Whenever someone buys a Big Mac, herbivores and omnivores alike pick up the tab for the burger's additional, externalized costs. This shifting of costs means each of us—rich or poor, sick or healthy, omnivorous or vegetarian—pays the true costs of these goods, not their producers. Further, contrary to the oft-repeated claim that producers pass low prices on to consumers, the externalization of costs does not really save us money because we simply pay the costs in other ways.

Of course, mass-producing just about any food generates external costs, and fruits and vegetables are no exception. Thus, growing crops for people imposes some of the same external costs on the environment that growing feed crops does, such as those arising from the use of pesticides and fertilizers. However, the external costs of growing fruits and vegetables are minuscule compared to those of producing animal foods. Plant-based foods, for example, generate virtually none of the health care costs and far less of the environmental costs that animal foods do.12 Moreover, government subsidies are heavily skewed toward animal food producers, who receive more than thirty times the financial aid that fruit and vegetable growers do.13 And like most features of meatonomics, these subsidies work in strange ways and have a number of unexpected consequences.§

US agriculture is propped up by an intricate scaffold of government subsidies that would make Rube Goldberg proud. These programs funnel cash and benefits to big farmers in a variety of ways that most nonfarmers have never heard of, including crop insurance, disaster payments, and counter-cyclical payments, to name just a few. Few laypeople understand how these complex programs work, how pervasive they are, or the unexpected places they crop up. I was surprised to learn, for example, of a massive water subsidy program for farmers a few hours from where I live in Southern California. In California's Central Valley, irrigation subsidies let farmers use roughly one-fifth of the state's water and pay only a small fraction of its value—about 2 percent of what Los Angeles residents pay for water.14

The farm subsidy system is filled with off-the-wall incongruities, the oddest of which lie in the federal government's conflicted policy agenda. On one hand, as we've seen, the USDA recommends in its Dietary Guidelines for Americans that we consume less cholesterol and saturated fat. On the other hand, it heavily subsidizes the foods that are the main sources of these substances—meat, fish, eggs, and dairy. On one hand, the Dietary Guidelines recommend that we eat more fruits and vegetables. On the other hand, the government designates these foods as specialty crops that are largely ineligible for subsidies. The net result: nearly two-thirds of government farming support goes to the animal foods that the government suggests we limit, while less than 2 percent goes to the fruits and vegetables it recommends we eat more of.15 (The USDA, by the way, officially declined to comment on this or any other issues in this book.)

Perhaps even more surprising than our government's muddled messaging on agricultural subsidies is the total dollar value of these subsidies. The USDA will spend $30.8 billion in 2013 supporting US farmers with loans, insurance, research, marketing assistance, cheap water, and other help.16 State and local governments will contribute another $26.5 billion, mainly in the form of irrigation subsidies.17 That's a total of about $57.3 billion in annual government subsidies to all segments of US agriculture—more than the entire annual government budget of New Zealand and twice that of the Philippines.

The lion's share of this subsidy largesse supports the animal food industry. Because most US corn and soybean crop is used for livestock feed, and most subsidies help farmers who grow these crops, most of the subsidies to US agriculture ultimately benefit producers of meat, eggs, and dairy. What kind of numbers are we talking about? One study estimates that 63 percent of US subsidies benefit animal food producers.18 Applying this percentage to the $57.3 billion farm subsidy total, and adding $2.3 billion for fish subsidies (see chapter 9), the total of annual subsidies to US producers of animal foods is an estimated $38.4 billion.19

These subsidies work in surprising ways, and it's enlightening to consider whom they help and hurt. Supporters of farm subsidies argue that these programs provide a number of benefits, including assisting small farmers, boosting rural development, stabilizing commodity markets, and promoting national food security. However, subsidies typically work in ways far different from those intended.

Let's start with some historical perspective. When the Depression hit in 1929, prices of farm goods fell like corn stalks in a gale. President Franklin Roosevelt responded with New Deal programs, including subsidies, designed to stabilize prices and boost small farmers' incomes. The system worked at first, but as large farms came to dominate the agricultural landscape, less and less of the subsidy funds wound up in the little guys' pockets.

Today, the handouts are aimed at big farming concerns. Taxpayers paid out $161 billion in direct payment farm subsidies between 1995 and 2009, but two-thirds of US farmers didn't receive a cent. The funds mostly went to big corporate players, with one-fifth of recipients grabbing nine-tenths of the cash.20 If the federal government sent invites to this party, those for small farmers were clearly lost in the mail. The 2013 farm bill (not yet passed as of this writing) seeks to end direct payments, the most controversial subsidy type, shifting the funds to crop insurance instead. But the cash and benefits will still favor the big guys over the little family operations. Moreover, not only do most of the subsidy benefits go to large corporations, but most of the beneficiaries are in the animal food industry.

It may come as little surprise, but the handful of farmers who consistently harvest the most greenbacks from crop subsidies, research shows, are livestock producers. The reason: corn and soybeans are the main items on the menus for livestock, accounting for the majority of feed ingredients in factory farms (where virtually all US farm animals are raised).21 This makes factory farms the biggest consumers of these subsidized commodities, and they buy most of the corn and soybeans grown in the United States.22 Fish farms, by the way, also rely heavily on corn and soy for feed.

The expense of feeding hungry animals is a huge part of the cost of doing business in animal agriculture. This food accounts for almost half the costs of raising hogs and nearly two-thirds the costs of producing poultry and eggs.23 But crop subsidies come to the rescue by helping producers keep their feed costs low. One study found that crop subsidies and the resulting lower feed prices allowed factory farms to decrease their operating costs by as much as 15 percent from 1997 to 2005, saving nearly $35 billion over the period.24 As these programs favor big operators over small, they not only fail their original purpose of helping small farmers, but they also go a step farther and actually help drive small farmers from the rural landscape.

The problem isn't just that small farmers don't get their fair share of the subsidy pool. It's also that in light of the unintended effects these handouts have on the market, small farmers are among the biggest losers under subsidy programs. Subsidies distort the normal market forces of supply and demand, making small farmers overproduce even when inefficient to do so. For an example of math that doesn't really add up, consider: when subsidies reduce the market price of corn to levels below what it costs to produce, US farmers nevertheless continue to grow it in record amounts.

From 1986 to 2005, the cost to grow corn was higher than its market price in every year but one.25 Yet because of market incentives to increase production levels, even as subsidy payments tripled during the second half of this period, farmers' net income fell by 15 percent.26 It's not hard to see why. Say the cost to produce a bushel of corn is $6, but the bushel can only be sold for $5.90. No one's going to grow corn at these numbers. But throw in a $1 per bushel subsidy, and now there's profit of $0.90 per bushel. But as production increases, and the excess supply causes prices fall to $5.50 per bushel, farmers grow more corn to make up the income shortfall. This in turn drives prices even lower. It's a vicious cycle, a perpetual pattern of false cues and financial suffering for many of its participants. As physician Martin Fischer said, “Morphine and state relief are the same. You go dopey, feel better and are worse off.”

Supply management—holding goods in reserve—once kept these harmful forces in check. Remember government cheese? In the 1980s, the Reagan administration famously tapped tons of dairy reserves to give processed cheese to the poor. Criticized as the patronizing and unhealthy product of unrealistic and out-of-touch leadership, the orange, five-pound blocks became synonymous with Reaganomics and government double-speak. Still, despite evidence that supply management works, at least from a market perspective, policy makers abandoned that system in the 1990s for a market-oriented approach that deregulates supply. The theory was that with less regulation, farmers would make better choices—like producing less when prices dropped. Unfortunately, it turns out the theory was wrong.

In the world of small farms, subsidies are a poisoned chalice. Depressed commodity prices and smaller margins hurt small farmers' incomes. Not surprisingly, USDA research indicates that even with subsidies, most farm families don't earn enough farm income to support themselves.27 Most of these families moonlight in off-farm activities, getting second (or third) jobs or engaging in other business activities to make ends meet.28 This decline in income and lifestyle leads most small farmers and rural Americans to oppose subsidies; nearly two-thirds of Iowans, for example, favor eliminating subsidies.29

The economic damage wrought by farm subsidies plays out regularly in rural communities across the country. In a 2007 article titled “Why Our Farm Policy Is Failing,” Time Magazine described the effect of subsidies on the small town of Randolph, Nebraska:

Randolph's school district has dwindled from nearly 1,000 students to fewer than 400. It's adopted a four-day week to save money and might switch to eight-man football. The town has lost its Ford, Chevy and Chrysler lots, all its implement dealers and lumber yards, its creamery, jewelry store and movie theater. “The big farmers took over, and it's killed small business,” says Paul Loberg, who runs a welding shop off Main Street. “All they need downtown is coffee and beer. They can't buy that by the truckload yet.”30

Subsidies also cripple small farming towns by promoting the growth of factory farms, or concentrated animal feeding operations (CAFOs). CAFOs are usually bad news for those who live nearby, saddling local regions with pollution-related costs and other burdens. Some locals might accept these consequences if CAFOs gave back to the community by providing jobs or buying goods. But CAFOs hire fewer workers per animal than smaller farms do, and they purchase most supplies from out of the area. Thus, as CAFOs enter a region, they cause declines in local business purchases, infrastructure, and population, turning once-vibrant communities like Randolph into ghost towns.31 Mike Korth, a farmer in Randolph, received $500,000 in subsidies over ten years but still publicly opposes farm welfare because of the damage it causes by spawning factory farms.32

Artificially low feed prices also give CAFOs a huge advantage over the dwindling number of smaller, traditional farms that still grow their own feed. As a result, over the last several decades, CAFOs have consolidated and gotten bigger. At the same time, traditional farms have gone out of business or sold off to their larger competitors, disappearing from the landscape by the millions. The number of US hog farms, for example, shrank by 76 percent from 1982 to 2002 although pork production increased by 10 percent during the period.33 As this trend continues, fewer small farms survive, and market power concentrates in the hands of fewer and fewer industrial producers. One analysis bolstered this point, finding that four beef packing firms control 84 percent of their market, and four pork packing firms control 64 percent of theirs.34 Animals, it seems, are not the only ones who are highly concentrated in factory farming.

Worse yet, the larger revenues generated by CAFOs routinely don't generate higher tax revenues for the states or localities where they do business. One study looking at state and local tax revenue from swine farms found that among all farm types, CAFOs generate the least tax revenue per pig.35 Local tax revenues also suffer because lower purchases from local businesses mean decreased sales tax receipts, lower property values in the vicinity of CAFOs cause lower property tax receipts, and property tax exemptions for CAFOs lead to lower tax revenue.36 The one-two punch of subsidies and CAFOs, it seems, has rural America on the ropes.

In addition to plowing over our own small farmers, US farm subsidies routinely hurt the little guys throughout the rest of the world. Because meatonomics heavily subsidizes feed crops like corn and soybeans, for decades US farmers have sold these crops on world markets at prices well below their cost of production. This is classic dumping—the selling of goods in a foreign market at less than fair value. In the British card game Beggar My Neighbor, one of the goals is to make neighboring players pay stiff penalties. In the real world, when nations dump, they burden their neighbors with genuine penalties in the form of severe economic and social disruption.

In developing countries, where 60 percent of the people still earn their living in farming and sometimes get by on income of $1 per day, the results of dumping can be catastrophic. Small farmers would ordinarily be challenged to compete against a large agribusiness merely because of the economies of scale enjoyed by the larger competitor. But these small farmers have an even harder time competing when subsidies permit the large business to consistently sell at prices below its own cost of production. This slanted playing field drives small farmers out of business and off their land, and it contributes to widespread socioeconomic problems in developing countries.

Dumping by US corporations has had devastating effects on a number of developing nations, including, by way of example, our neighbors to the south. The influx of cheap US corn flattened Mexican corn prices by 70 percent from 1994 to 2003, contributing to a 20 percent drop in Mexico's minimum wage and helping boost the nation's unemployment rate to 50 percent.37 In an ironic twist, when Mexicans seek employment in the same US industry that helped put them out of work, those lacking documents are rounded up, in some cases prosecuted, and deported. It's not just a metaphor—we have literally beggared those around us, and for some, validated the words of journalist Mignon McLaughlin: “Few of us could bear to have ourselves as neighbors.”

But it's not just our close neighbors we hurt by dumping. It's almost any farmer in the third world. In virtually every developing country where local farmers eke out a living growing commodities that are subsidized in the United States, our policy contributes to reduced incomes, increased unemployment, loss of land, and a decline in quality of life.38 In short, our subsidy programs damage third world economies. As one study found, “Subsidized agriculture in the developed world is one of the greatest obstacles to economic growth in the developing world.”39

American officials recognize the problems inherent in dumping, even though restraining the subsidy leviathan may be beyond their power. As former US Deputy Secretary of Agriculture Charles Conner said of the 2008 farm bill:

This farm bill just heads in the wrong direction in terms of our international obligations. It's no secret our current farm programs under current law have come under enormous fire for their adverse impact on developing regions of the world and their ability to increase their agricultural production because they can't compete against the farm subsidies of the developed world. How does this bill respond? This bill responds by increasing trade-distorting supports on seventeen out of twenty-five of the commodities that we provide. This is moving, clearly, in the wrong direction in terms of helping the world sustain themselves through food production.40

What does the dumping of corn and soybeans have to do with meatonomics? Follow the money. Recall that in the United States, most of these crops are fed to livestock and fish—making American animal food producers the main beneficiaries of feed crop subsidies. These producers use their economic and political clout with remarkable success to convince state and federal lawmakers to create and maintain subsidies for feed crops. As noted, one study found that every $1 in campaign contributions that agricultural donors gave lawmakers yielded an investment return of about $2,000 in subsidy payments.41 It's these subsidies, in turn, that cause the dumping of commodities used as livestock feed (like corn and soybeans) in the third world. As the United States is the planet's largest corn supplier, providing half the corn consumed by people and animals on Earth, our subsidy practices have huge consequences for the rest of the world.

We've seen that the massive handouts Americans give to big agriculture hurt taxpayers, consumers, and small farmers in both the United States and developing countries. The animal food industry is one of the rare beneficiaries of these subsidies, but it's not the only one. Those who provide key supplies to agriculture—known as inputs—also benefit from government subsidies that keep feed prices low. These input suppliers include equipment manufacturers like John Deere, chemical companies like Dow, and seed companies like Monsanto.42 Crop subsidies encourage farmers to grow more crops, and of course the more they grow, the more seeds and tractors they need.43 The fact that subsidies seem to be paid to the small farmers who consume these resources is merely an illusion; a political sleight of hand (remember the vastly undersized percentages that actually go to those farmers). Like a cruel practical joker, the government waves an envelope of cash in front of a small farmer—and maybe even lets him hold it briefly—but ultimately slips it into the pocket of an executive or shareholder in a large multinational corporation like Monsanto or Tyson Foods.

For their part, executives and shareholders in the handful of corporations that actually benefit from subsidies are living high off the hog. In the meat industry, shareholders in public companies enjoy nearly $4 billion in extra shareholder equity and roughly $228 million in annual dividends thanks to subsidies.44 Tyson Foods, Inc., is the largest processor of chicken, beef, and pork in the United States and the second largest in the world, with more than a hundred thousand employees in more than 3,200 facilities. In 2010, Tyson paid shareholders $59 million in dividends; it also paid its CEO $4.8 million in compensation and its chief operating officer $4.9 million. Yet these and many other rich benefits were, in effect, paid completely by taxpayers. Research suggests that government crop subsidies in 2010 let Tyson pocket at least $3.5 billion in savings.45

Farm policy is like the weather: everyone complains about it, but no one does anything to change it. Every five years or so, Congress passes a massive farm bill with enough pork in it to satisfy just about everyone. In 1973, farm-state lawmakers shrewdly ensured the continuing support of urban lawmakers by adding food stamps to the farm bill. With more than 46 million Americans, or one in seven, now receiving food stamps, the farm bill is as firmly entrenched in American political life as apple pie and Social Security.

That is to say, entrenched but hated. As the New York Times noted following the 2008 farm bill's passage:

Few pieces of legislation generate the level of public scorn consistently heaped upon the farm bill. Presidents and agriculture secretaries denounce it. Editorial boards rail against it. Good-government groups mock it. Global trading partners formally protest it. Even farmers gripe about it. But as Congress proved again last week, few pieces of major legislation also get such overwhelming bipartisan support.46

Republican Senator John McCain opposed the 2008 farm bill, saying: “It would be hard to find any single bill that better sums up why so many Americans in both parties are so disappointed in the conduct of their government, and at times so disgusted by it.”47 McCain reiterated his frustration four years later over the 2012 farm bill (which failed to pass Congress and was retooled as the 2013 farm bill), saying he was “hard-pressed to think of any other industry that operates with less risk at the expense of the American taxpayer.”48 Yet despite the occasional eleventh-hour drama, every farm bill eventually passes—mainly because there's a little something in it for everyone. It's a bizarre feature of US lawmaking that a bill's overall effect can be awful, but it will still pass if its individual components gratify enough special interests or regional constituencies. As Steve Forbes said, “Once a pork barrel scheme is started, nothing in heaven or on Earth is likely to stop it. Like barnacles on a ship, too many vested interests will glom onto it and fight to protect it.”49

The market distortion and social disruption that farm handouts cause might be understandable if subsidies at least helped the taxpayers who write the checks. However, taxpayers are also major losers in the American farm subsidy system. According to one group of researchers, our subsidy program merely “shifts the burden of supporting farmers from . . . purchasers to taxpayers.”50 How much are these subsidies really worth to taxpayers, in their alter-ego roles as consumers, at the cash register? Not much, it turns out. An estimate in Appendix C shows that eliminating three-quarters of US animal food subsidies would raise prices by only about 1.8 cents per dollar of retail sales.51 By contrast, for each dollar of animal foods sold at retail, producers shift $1.70 in external costs to taxpayers. In other words, taxpayers get almost none of the benefits of subsidies but all their costs—including, particularly, the damaging market consequences that subsidies foster.

Most commentators agree the agricultural subsidy system needs fixing, and many believe the best fix is to return to an unsubsidized market. But even if lawmakers suddenly found the political will to start dismantling the subsidy program, which is unlikely without massive public pressure, there would be no quick fixes. What does all this mean for American consumers? Many are challenged just to support their loves ones, or as George W. Bush clumsily said, “to put food on your family.” Few want to see subsidies cut if the result is to raise meat and dairy prices. Yet there is a solution that, evidence shows, can benefit society across the board by lowering external costs, reducing disease, saving lives, and protecting the environment. That proposed solution is discussed in chapter 10. In the meantime, let's explore the other costs that the animal food industry imposes on society.

§ Although subsidies are typically not considered an externalized cost, they are included in this category for calculation purposes because, just like external costs, subsidies artificially depress prices and increase consumption, and they impose a large social burden without providing any real benefit to most consumers or taxpayers.