Become the Brewer

Brewing Beer in the Real World

When we first conceived of this book, we said, “Let’s write a book so that people can see how easy homebrewing can really be.” But, here’s the thing…brewing ain’t that easy. Drinking beer is easy, but making beer is a bit of a process. Now, it certainly isn’t that hard, but in our day and age, when the definition of easy in the food world means peeling back the corner of the package and heating on high for 2 minutes, homebrewing is definitely a labor of love (but not as hard as child labor, so there’s that).

There’s a lot of careful consideration and patience required in homebrewing. There are ingredients to understand, temperatures to check, and boiling times to watch. There is some special equipment you’ll have to buy (unless you’re really into blowing your own glass). You need to keep most of your equipment clean and sanitized. And sanitizing isn’t much fun. So there’s a lot going on here. We have, however, throughout our homebrewing journey, come to learn a few tricks of the trade and have been given some very good advice, including some rule-breaking shortcuts and tips that have resulted in homebrews that taste great and are relatively easy to make. We hope these methods are helpful and useful and will save you a lot of time and/or anguish.

The bottom line (and what inspires our homebrewing), is that it’s totally worth it! Drinking beer that you brewed yourself is so, so gratifying. It’s like growing your own vegetables or baking your own bread or pickling your own cucumbers. It takes a while, but when you finally consume your own homebrew, your chest swells with pride at the thought that “you did this all yourself!” Oh, and also that it’s beer, and you love beer. And the process of brewing that beer elevates your appreciation of beer to an entirely new level. If beer is your favorite drink, and statistics show that it is, then you will learn more about beer brewing than you could drinking all of the beers in the world. You will birth beer (too much?), and you will fall in love with beer all over again.

Why We Brew Smaller

The recipes in this book are for 21⁄2 gallons of beer, which makes approximately 24 (12-ounce) bottles. Why such a small batch? We started out making 5 gallons, which is what most people do when they start because most of the recipes out there are for 5 gallons. The common feeling being, if you’re going to spend a few hours brewing something and then many weeks fermenting and conditioning, you might as well make as much of it as you possibly can. That argument does make a lot of sense. It’s great to get a lot of beer out of the ingredients and the process. However, we don’t throw a party every weekend, and we’re urban dwellers with relatively small living spaces and pretty tiny kitchens. One 5-gallon batch makes about 48 (12-ounce) bottles of beer. If you’re brewing this size consistently, the amount of beer that you end up with (even after drinking as much as possible) seems endless. The bottles, kegs, and fermenters will start to spill out of your fridge, closets, and basement. In fact, one day one of us couldn’t take a shower because of the fermenting buckets occupying the bathtub. We started to wonder if this qualified as hoarding. It was time to take it down a notch.

Upon doing so, we found that there were many other advantages to smaller batches than just saving space. Smaller batches are, in general, much easier to deal with. You can get a smaller amount of liquid to come to a boil faster. Inversely, it’s easier to cool down a smaller batch of beer, an essential step that needs to happen quickly in homebrewing. You don’t need as much stove power, which is very helpful, especially with cranky or electric stovetops. Another plus is that small batches are so much easier for us to lift, transfer, and generally maneuver, especially when we’re brewing alone. We aren’t giant dudes, so working with a size that we can lift is important to us.

The other great thing about small batches is the feeling that if you screw it up, you don’t have 5 gallons of shitty beer to drink. You have half that, and you can drink, dump, or cook with it without feeling too pathetic or wasteful. With small batches, we feel free to experiment and try, try again without too much hassle. Having said all that, if you are having a party and want to brew 5 gallons, our recipes can easily be doubled for a larger batch. It’s a good idea to check the numbers in a beer software program, like BeerSmith or BeerTools (see “Homebrew Resources” on page 289), when doubling a batch, so that you get the beer stats you desire.

So, How Is It Done?

BASIC STEPS

The following list makes up the bare-bones basic steps to making beer, in order of when they are done and our honest feelings about performing them:

OK, so that’s the basic truth of it. See, it’s not easy, but it’s not hard, and in the end we promise you’ll feel that euphoria we feel. Here’s an in-depth look at each step:

1. Steeping/mashing the grains. You will not need this step if you are making a beer entirely from extract. This is for recipes that use (1) extract with specialty grains that steep like tea and are added to your brew to lend it color and flavor; (2) recipes that use the partial-mash method, in which the grains are steeped and kept at a controlled temperature long enough to extract flavor, color, and fermentable sugars before they are added to the boil with extract; and (3) all-grain recipes that use no extract. This book has mostly extract and specialty grain recipes, although there are a few partial-mash and all-grain recipes. Specific instructions are included with each recipe.

Steeping grains means placing the specialty grains called for in the recipe into a grain bag, closing up the bag, and placing it in a pot of water that has been heated up to 160°F. You’ll cover the pot and let the grains steep for 30–60 minutes for most recipes. Then you’ll carefully open the top of the grain bag and pour a specific amount of 170°F water over the grains to make sure you’re getting most of the good flavors. This act of pouring the hot water is called “sparging.” Sparging is not crucial when you’re simply steeping grains; most of the flavor has already been extracted during the steeping time in the pot. But sparging is very important in partial-mash and all-grain brewing. The colorful, flavorful liquid that remains from the steeping will be added to the boil.

If the recipe calls for a partial mash or all grain, you’ll need to do a mash at the temperatures and times listed in the recipes. For partial-mash recipes, in which most of the fermentable sugars are coming from the extract and we are mostly getting flavor, color, and texture from the specialty grains, we usually mash for 30 minutes. For all-grain recipes, in which we are getting all of the fermentable sugars from the actual grains, we will mash for anywhere from 30 to 90 minutes.

2. Boiling the wort. This is the time when the wort is brought to a boil and hops are added to extract their flavors. Boiling also, among other things, helps many of the proteins (which can be harmful to the beer) clump together and drop to the bottom of the brew kettle. This is known as the “hot break.” Achieving a hot break helps remove the worst of these proteins, which can cause instability or off-flavors in the beer. This is very important for partial-mash and all-grain recipes. Boiling for an hour is less important in all-extract brewing, in which the majority of harmful proteins have already come to a break during the process that produces the extract. Boiling the wort is crucial for achieving hop characteristics; the longer you boil hops, the more bitterness you extract.

3. Adding the hops. As we’ve mentioned, hops are responsible for any bitterness and dryness you detect in beer. They also balance the beer, which would be very sweet and cloying if there were no hops in the recipe. Hops can also add flavor and aroma, depending on the beer. They have the added bonus of being a natural preservative. There is usually at least one hop addition, meaning a point during the boil when you add the hops, but sometimes there are many more. So for example, you may add hops at the beginning of your boil that lasts 60 minutes, then you might add more hops at 30 minutes, and then yet more at 5 minutes. Multiple additions affect the bitterness, measured in International Bitterness Units (IBUs), as well as the flavor and aroma of your beer. There are many different kinds of hops, and each impart different IBUs and flavors to the beer (see “Hop Chart” on page 293).

4. Cooling the wort. Before adding your yeast to the brew, you have to get your just-boiled wort down to about 70°F. This, and sanitizing, is one of the most annoying parts of brewing. It takes a bit of patience to cool down a large amount of liquid. This is part of why we like to brew in small batches, it’s quicker to cool 21⁄2 gallons than 5 gallons. We like to use our sink or a large bucket (plastic or metal) and fill it with cool water, ice, and ice packs. We then put the brew pot in this cold bath and use a sanitized floating thermometer to check on the temperature until the liquid is ready for the yeast. If your sink is too small, you can invest in the large bucket. If you don’t want a bucket lying around (though it comes in handy as an ice vessel for cooling bottles and cans of beer when you throw a party) and your sink is too small, you can use a bathtub. If you don’t use an ice bath and let your wort cool down by just leaving it at room temperature, it will take a long time and you increase the chances that bacteria will fall into your wort, which can spoil your beer and affect the yeast.

5. Sanitizing. OK we admit it, this is the most pain-in-the-ass part of homebrewing. Who really likes to clean and sanitize? Not us (we’re not exactly Susie Homemaker types), but sanitizing is one of the most important steps of the homebrew process. If you brew with equipment that is dirty or holds bacteria, your homebrew can become funky, infected, and taste off. Trust us, treat this step with reverence. There’s nothing more aggravating than going through the process of homebrewing only to find you’ve spoiled your work by poor sanitation procedures. Having said that, we’re not super OCD about cleaning and we don’t go crazy, but we do what is suggested and do our best. We don’t sterilize like a surgeon but sanitize to keep our beer relatively safe. Remember you need to clean the pieces of your brew kit before you sanitize them, you can’t just throw the sanitizer into a bucket that contains beer or yeast residue and hope for the best. So clean your brewing equipment first, rinse the soap, and then sanitize.

Sanitation is not just cleaning your brewing equipment, you need to use a sanitizer to get rid of all the bad stuff you can’t see with your naked eye. So you’ll need to buy a sanitizer. We use iodophor, which is an iodine-based product. You drop a few drops into water and it will sanitize your equipment. You can use bleach if you are very careful to wash it away afterward because it can make you sick or ruin your beer otherwise. It’s very important to use the proper amount of sanitizer for the appropriate amount of time, as advised on the bottle. If you don’t use enough, it will not kill any bacteria, if you use too much, the residual amount left on your equipment could affect you and your beer. Cool to room-temperature water is ideal for sanitizing and agitating may help. You typically want to sanitize all of your equipment that will come into contact with your freshly made wort. In other words, everything that will go into the boil will be sanitized by the boiling water, but anything that touches your wort after the boil must be sanitized. This is the point at which bacteria can get into your beer and do nasty things.

Here are some sanitizing options:

Pills Are Good…

WHIRLFLOC TABLETS

WHIRLFLOC TABLETS

A Whirlfloc tablet is what we call in the homebrewing world a “clarifier,” which means it helps coagulate and settle proteins and beta-glucans that exist in your wort. In layman’s terms, Whirlfloc tablets help refine your beer. We love these tablets and use them in any beer for which we want a really sparkly clear finish. Now before you get all upset about putting additives in your homebrew, know that this quick-dissolving tablet is a blend of Irish moss (carrageenan), which is a species of red algae that grows naturally along the Atlantic coast of Europe and North America. When we use the tablet, we add it right at the very end of our boil with just 5 minutes remaining. According to the manufacturer, if Whirlfloc is in the boil for any longer than 10 minutes, the active ingredients become denatured and therefore will not do their job.

Campden tablets are kind of a brewers’ and winemakers’ secret. In addition to dechlorinating water, the tablets, which are potassium or sodium metabisulfite, are also used to kill some bacteria and halt some fermentations. They’re just good things to have around if you’re a homebrewer. We use these tabs to treat our water when we detect off flavors and aromatics. To add the Campden tablets to your water, just crush them to a powder with the back of a spoon, add it to your brew-pot water before the boil and stir to dissolve.

You can find both of these tablets at your homebrew shop or online for supercheap. Because of the size of our batches and because we are—ahem—frugal, we usually cut them and use only half a tablet of either Whirlfloc or Campden in a 21⁄2- to 3-gallon batch.

6. Pitching the yeast. Once your wort is chilled down to 70°F or below, you can transfer the wort by pouring it through a sanitized strainer into a plastic bucket or through a sanitized strainer and funnel into a glass carboy. Then pitch the yeast, which basically means dumping the yeast into the cool wort. Technically, the person who pitches the yeast is the actual brewer of the beer. So take a moment and be proud of yourself at this point, you are about to begin the fermentation process! Remember to sanitize the outside of the yeast vessel by dipping it into your sanitizing solution. This will get rid of any bacteria hanging out on the package that may find its way into the beer. A couple of important things to remember so that your pitching is effective:

Let It All Out: Airlock and Blow-Off Tube

When you transfer your cooled-down wort into your fermentation vessel, you will need to cover it, so that bacteria, flies, and other things don’t get in and ruin your beer. But you also need to make sure that some air can get out because CO2 is a natural byproduct of the fermentation process. The answer is an airlock and stopper or a blow-off tube. An airlock is a plastic deal that has one narrow end that sticks into the hole in a plastic bucket lid or plastic stopper that is placed into the top of a carboy. The airlock is filled halfway with vodka or a similar alcohol to protect the beer and covered with its plastic cap, which has tiny holes in the top. It sounds complicated, but it’s not at all.

When you transfer your cooled-down wort into your fermentation vessel, you will need to cover it, so that bacteria, flies, and other things don’t get in and ruin your beer. But you also need to make sure that some air can get out because CO2 is a natural byproduct of the fermentation process. The answer is an airlock and stopper or a blow-off tube. An airlock is a plastic deal that has one narrow end that sticks into the hole in a plastic bucket lid or plastic stopper that is placed into the top of a carboy. The airlock is filled halfway with vodka or a similar alcohol to protect the beer and covered with its plastic cap, which has tiny holes in the top. It sounds complicated, but it’s not at all.

The other option is to use a blow-off tube. We use this method when (1) we think that we’re going to have a huge fermentation that could clog or blow off our airlock and possibly contaminate our beer or blow up our fermenter or (2) we don’t have enough headspace in the fermenter, which could result in clogging or blowing off our airlock and possibly contaminate our beer. Making a blow-off tube is simple. First, get 3 feet of 3⁄8-inch vinyl tubing from your local homebrew shop and fit it through the hole in the rubber stopper that you use for your airlock. The other end of the tubing should go in a bucket or pitcher of water. You’ll start seeing the CO2 bubbles in the bucket or pitcher of water, and you’re good to go without threat of contamination or personal injury.

7. Waiting for fermentation. The hardest part, no doubt, is waiting for fermentation. Beer needs time for the yeast to eat the sugar from the malt and create the byproducts of alcohol and CO2. At the least, beers need about 5 days to ferment, but we recommend giving it seven to ten days. You just have to be patient and let your beer be. Beer should ferment out of the sun in a fairly constant-temperature part of your home. We recommend using your large bucket, filling it with a bit of room-temperature water and setting your fermentation vessel in that. The water helps keep the beer at a constant temperature. Some beer styles take longer than others to ferment. You will know fermentation has started when you see bubbles coming up in your airlock or through your blow-off tube. We typically recommend a second period of waiting called “secondary.” This is when you move the beer to another vessel to take it off of the yeast and let it sit for a bit longer. This usually makes a better beer. You are taking the beer off of yeast that is dying and thus can produce off-flavors in your beer. To make it through fermentation without whining, you’ll need plenty of beer on hand to drink.

8. Bottling or kegging. Once your beer is fermented, it’s time to put it into a bottle. This is where the beer will gain a bit more carbonation. If you taste it out of the fermenter (and you should), it will be a bit flat. This is the natural state of the beer, but most beers that you drink at the pub or from a bottle you bought at the store, have been force-carbonated. This means that CO2 has been added, so that the beer is nice and sparkly. To do that at home, you have to add priming sugar.

9. Waiting. Even harder than waiting for the beer to ferment is waiting for the beer in the bottle to carbonate. Usually this takes anywhere from 7 days to 2 weeks. It usually helps to pop one open to test it when you can’t stand waiting any longer. If you hear that familiar fssst sound, you know you’re on the right track.

10. Drinking. Self-explanatory.

How to Bottle (So You Can Drink Your Beer)

Before you bottle, it’s best to make sure your fermentation is done. If you bottle your beer too early, you could have some exploding bottles on your hands or simply overcarbonation. Carefully take a sample from your beer and check the specific gravity with your hydrometer. It’s best to check again in two days to make sure the number is the same. This will verify that fermentation is finished.

STEP BY STEP

1. Sanitize everything; and by everything we mean:

Your bottles

Bottle caps

Tube siphon

Bottle filler

Bottling bucket (3- to 5-gallon plastic fermenting bucket)

The easiest way to do this is to wash them all first, and then fill your bottling bucket with water and the appropriate amount of sanitizer based on the directions on the sanitizing bottle. Then soak everything in the sanitizing solution. Remove everything and place on paper towels. Empty the bucket and use it as your bottling bucket.

2. You will also need to have the following on hand:

Bottle capper

Priming sugar (corn sugar or white table sugar)

3. Set your bottles upside down on paper towels or better yet on a bottling rack (something else to buy) to drain, taking care not to contaminate them.

4. In general for a 21⁄2-gallon batch of beer, boil 1 cup of water, take it off of the heat and then add either 2 ounces of corn sugar or 1⁄3 cup of white sugar and let the mix cool. If you want to get the carbonation just right for the style of beer you are brewing, you can use the handy priming solution calculator available at TastyBrew (www.tastybrew.com/calculators).

5. Gently pour the priming solution into your bottling bucket. Now you need to transfer your beer into the bottling bucket, taking it off of unwanted yeast sediment, and mix it with the priming solution. To do that, use your sanitized tube siphon, and gently, ever so gently, transfer the beer into the sanitized bottling bucket. You do not want the beer to splash or to aerate at this point. Make sure to leave the sediment from the fermenter behind.

6. Once you’ve transferred all your beer into the bottling bucket, and the priming solution is evenly distributed into the beer, it’s time to bottle. Attach your bottle filler to the tube end of your tube siphon, place the bottle filler into a bottle, carefully siphon your primed beer into the bottle. Fill the bottle by pressing down on the bottle filler on the bottom of the inside of the bottle to let the beer flow. Simply lift the bottle filler to stop the flow of beer and move on to the next bottle. Fill the bottles to just below the top, leaving about an inch gap.

7. Once your bottles are filled, cap them with crown seals as quickly as you can with your hand capper.

8. Store the beer at the temperature (or room temperature) and time listed in the recipe.

9. Now you wait for the bubbles. While the rest of the yeast in the beer eats the tasty priming sugar in your beer and farts out CO2 bubbles, you have to be patient once again. You’ll have to let your bottles sit at room temperature away from sunlight. You can taste the beer along the way to see how it’s coming, but you really should wait at least 2 weeks for the beer to be at its best. Then you can refrigerate and move on to the last step.

10. Congratulations! You made beer! Now drink it! Be sure to get a nice well-made glass and take notes on your first tasting. Note the color of the beer, the head retention, OG, FG, carbonation, ABV, flavor, hop character, yeast character, and everything you smell and taste in your beer. It’s very important that you take note of where you went right and what may be off about your brew. Next time you make the recipe you can compare and contrast to these notes, and this, more than anything else, will improve your homebrewing. Be sure to share your beer with your friends; we love the look of pride on a homebrewer’s face when she brings a homebrew over to share with us. Homebrewed beer really is the most impressive beverage you can bring to a party, so be sure to share and get the praise you deserve.

Beer Stats: ABVs, IBUs, OGs, FGs, Ls, and SRMs

There are a few abbreviations that you need to know for brewing. These will pop up in our recipes and most other recipes you come across. You can just nod and smile when a fellow homebrewer asks if you hit your OG with your homebrew and are happy with your SRM and ABV, but it’s much better to know what the hell that person is talking about.

ABV (Alcohol by Volume). This directly relates to how drunk you are going to get. If all you’ve had are the mass-produced Lagers, the beers that you’ve been drinking are probably between 3% and 5% Alcohol by Volume. When you start getting into craft beers, the ABVs can range from what you are used to (3% to 5%) to big beers (anywhere from 6% to 20%; watch out!). If you’re going to drink a beer, or a few, you’d better know your ABVs. Believe us when we tell you that there is a huge difference between a 5% beer and an 8% beer. A 5% beer can make you friendly; an 8% beer can make you French-kiss a tree. Of course this all depends on how well you can hold your liquor. Can you handle your martinis or do you get sauced after half a glass of Pinot Gris? It’s critical, especially for women, to be vigilant about how much alcohol we are actually consuming. Know your ABVs and you, your neighbor, and the tree in her garden will thank us.

IBU (International Bitterness Units). The IBU scale provides a way to measure the bitterness of a beer. The number on the bitterness scale is a result of some complicated empirical formula using something called a spectrophotometer and solvent extraction. We don’t pretend to understand that, and the good thing is that you don’t have to understand it either. The bottom line is that this scale was based on tasted beer samples and correlating the perceived bitterness to a measured value on a scale of 1 to 100. On this scale, the higher the number, the higher the concentration of bitter compounds in the beer. For example, a mass-produced American Lager might have an IBU of 5, whereas a Double IPA might be somewhere around 90 IBUs. Some brewers are starting to put this number on bottle labels, but more often than not, this number is not shown on the actual beer. If you’re worried about bitterness, it will help to know the general range of IBUs for each beer style. We encourage you to use your own palate to determine bitterness, as the IBU scale can be a bit confusing for newer craft beer drinkers. Some of the more advanced drinkers, and those who are adept at brewing, may begin to pay closer attention to these numbers. You can generally find the IBU number for a beer on the brewery’s website. For an IBU range for beer styles, check out the Beer Judge Certification Program’s website (www.bjcp.org/index.php).

OG (Original Gravity). No, not that OG; this OG is a measurement of the weight of your wort compared to the weight of the water. This is measured before fermentation and will help you determine the strength of your beer after fermentation.

FG (Final Gravity). This is the same measurement as OG, but taken after fermentation. Using the OG and FG, you can figure out the alcohol by volume of the beer.

L (Lovibond). This is a measurement of the roast level or color of a particular malt and/or the color of a beer. For example, one Caramel/Crystal malt may have an L of 60, whereas another may have an L of 120, the 120 being a darker level of color. This is important when you’re trying to produce a certain color in your beer.

SRM (standard reference method). This is a measurement of beer color much like Lovibond. It is a newer measurement than Lovibond but is similar. Each beer has a general guideline for color, you don’t have to be strict with this, but it is nice to make sure, for example, that your amber won’t be too dark. The SRM in recipes and recipe-calculating software will help you find the color you want in a particular beer.

Calculating Alcohol

We’ve actually done quite a bit of brewing in the past not knowing what our alcohol content was, just having faith and being content with knowing that there was some alcohol in there somewhere. Now, however, we’re a little obsessed with knowing how we did. You never really have to do this (you can find out how alcoholic it is using other empirical data, like how tipsy you get), but if you want to find out exactly how much alcohol is in your beer, you need to take some readings with a hydrometer or a refractometer. We’ve provided target numbers for you to hit for each recipe. Here’s how you figure out the ABV in your homebrew:

We’ve actually done quite a bit of brewing in the past not knowing what our alcohol content was, just having faith and being content with knowing that there was some alcohol in there somewhere. Now, however, we’re a little obsessed with knowing how we did. You never really have to do this (you can find out how alcoholic it is using other empirical data, like how tipsy you get), but if you want to find out exactly how much alcohol is in your beer, you need to take some readings with a hydrometer or a refractometer. We’ve provided target numbers for you to hit for each recipe. Here’s how you figure out the ABV in your homebrew:

Or, just plug in your OG and FG into an online calculator. We like the one at Brewer’s Friend (www.brewersfriend.com/abv-calculator).

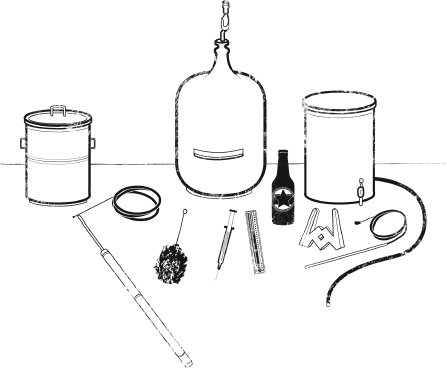

It’s time to put together your homebrew kit. Your local homebrew supply store will have most, if not all of these items. The Internet of course has everything, and you can pick and choose among different sites and compare prices. Many stores and websites will offer a “homebrew kit” that includes all of these items. Here are some sites we recommend:

HERE’S ALL YOU REALLY, REALLY NEED TO BREW

WHAT WE HAVE IN OUR KIT AND WHAT THESE THINGS DO

The Dipstick Trick

Late one night at the hazy end of our homebrew club’s annual holiday party after many samples of homebrew, we were feeling free enough to share what we each hated about homebrewing. Measuring was our loud, slightly slurred, complaint. To which a brewing genius replied, “Why don’t you just use a dipstick?” After we figured out he wasn’t insulting us, we listened intently as he explained. “Get an 18-inch plastic brewing spoon (that you’ll use for brewing anyway), then pour known amounts of water into your brew pot to ‘calibrate’ the spoon as a dipstick. Notch the spoon with a knife or mark it with a permanent marker at 1⁄2-gallon intervals as far as you need to.” Voilà! No more measuring and pouring (for the most part)! The suggestion was duh simple but so perfect.

Late one night at the hazy end of our homebrew club’s annual holiday party after many samples of homebrew, we were feeling free enough to share what we each hated about homebrewing. Measuring was our loud, slightly slurred, complaint. To which a brewing genius replied, “Why don’t you just use a dipstick?” After we figured out he wasn’t insulting us, we listened intently as he explained. “Get an 18-inch plastic brewing spoon (that you’ll use for brewing anyway), then pour known amounts of water into your brew pot to ‘calibrate’ the spoon as a dipstick. Notch the spoon with a knife or mark it with a permanent marker at 1⁄2-gallon intervals as far as you need to.” Voilà! No more measuring and pouring (for the most part)! The suggestion was duh simple but so perfect.

For some people, heading to the homebrew supply store can be like a hikers’ trip to REI, where you leave the store with all kinds of gadgets and gear that often end up being underused, shall we say. We want brewing to be as easy and as cost-efficient as possible, which is why we’ve already listed what we think are the essentials in a beginner’s brew kit. However, having brewed for a while now, we’ve picked up some gear that we have found to be very helpful—not essential for brewing—but really helpful for measuring ABVs more quickly, taking temperature readings faster, and getting our wort boiled and cooled faster. If you’ve found that you’re really into the homebrew thing and are willing to invest a little more money into your habit hobby, here’s what we’d suggest getting next:

For some people, heading to the homebrew supply store can be like a hikers’ trip to REI, where you leave the store with all kinds of gadgets and gear that often end up being underused, shall we say. We want brewing to be as easy and as cost-efficient as possible, which is why we’ve already listed what we think are the essentials in a beginner’s brew kit. However, having brewed for a while now, we’ve picked up some gear that we have found to be very helpful—not essential for brewing—but really helpful for measuring ABVs more quickly, taking temperature readings faster, and getting our wort boiled and cooled faster. If you’ve found that you’re really into the homebrew thing and are willing to invest a little more money into your habit hobby, here’s what we’d suggest getting next:

Brewing Vocabulary

If you’re going to brew the beer, you’d better know how to talk the talk. Here are some basic brewing terms you should familiarize yourself with, so you don’t feel lost at the homebrew supply store:

Top 10 Brewing Don’ts

1. DON’T MISHANDLE YOUR GRAINS

1. DON’T MISHANDLE YOUR GRAINS

Although they don’t look it, grains are delicate creatures. If you overmill or overcrush your grains into powder, oversteep your grains, or if you steep or sparge your grains with boiling (too hot) water, you can get a super mouth-puckery, cotton-mouthy astringency. (This is sometimes desired in certain styles, such as an IPA.)

2. DON’T BE DIRTY

OK, we know we mention this to the point of annoyance, but make sure that you sanitize, sanitize, sanitize! A bacterial infection from any number of sources is the number one cause of off-flavors in beers. Contamination can make your beer taste like vegetables and corn. It can also make it sour and downright funky. Bacteria can also be responsible for off-flavors called phenols, which taste like Band-Aids, again, an unwanted flavor in most styles, or anything really.

3. DON’T COVER YOUR BREW POT WHILE BOILING

There’s this thing called dimethyl sulfide, or DMS for short, that is released from the wort during the boil. If you cover the wort, the DMS will not be removed because the DMS condensation rejoins your wort. This can result in notes of seafood and shellfish. Seafood is unacceptable in any style (except maybe Oyster Stout! but not really even then).

4. DON’T UNDERAERATE YOUR COOLED WORT

One thing yeast loves when it begins the fermentation process is oxygen. And while it’s not always good to aerate your beer (for instance, you don’t want to introduce oxygen to hot wort or when transferring your beer into secondary), just before and after pitching the yeast is prime aeration time, baby. Make sure to stir or shake your cooled wort before and just after adding your yeast. Lack of aeration at this time can result in solvent, off-flavors, and buttery or slick butterscotch notes that brewers call “diacetyl.”

5. DON’T UNDERPITCH YOUR YEAST

In our recipes, we’ve allowed for the correct yeast amount, but as you start to come up with your own recipes, it’s important that you pitch enough yeast into your wort to have an active fermentation. Underpitching can also cause the aforementioned off-flavors and aromatics.

6. DON’T LET YOUR BEER FERMENT AT TOO-HIGH TEMPERATURES

Except for a couple of specialty yeast strains, most beer should be fermented below 80°F. High temperatures can kill your yeast and produce harsh hot or solvent characteristics. Brewers call this off-flavor “fusel” or “fusel alcohol.”

7. DON’T AERATE YOUR BEER AFTER FERMENTATION

OK, so here it is: Aerate your cooled wort before pitching your yeast. Do not aerate your beer after fermentation, at which point you should be very careful in handling and transferring, using a tube siphon for the latter. Aerating fermented beer can result in oxidation, which creates wet dog and cardboard flavors, and aromatics. Again, this is OK in some styles—like Old Ales and Barley Wines, but not OK in most.

8. DON’T REMOVE YOUR HOMEBREW FROM THE YEAST TOO SOON

Young beer can have flavors and aromatics of green apples (where you don’t want them). Brewers call this off-flavor “acetaldehyde.” This can also be an indication of a bacterial infection and the cause of buttery diacetyl flavors.

9. DON’T LET YOUR BEER SIT ON THE YEAST TOO LONG

So yeast are unfeeling little buggers, and when they’ve been sitting around a little too long on top of each other, guess what? They start to eat themselves. That’s right, it’s yeast cannibalism, otherwise known to brewers as “yeast autolysis.” When this happens, the worst of the worst off-flavors occur. Unmistakable characteristics of rotten eggs or sulfur emanate from your homebrew.

10. DON’T BOTTLE YOUR BEER IN CLEAR OR GREEN BOTTLES

The most popular off-flavor that people recognize in beer is skunkiness. A beer gets skunked because of a chemical reaction that takes place in beer when ultraviolet (UV) light hits the invisible hop components in beer. Be sure you bottle your beer in dark brown glass (nope, not even blue) to avoid the dreaded skunked beer!