CHAPTER TWO

Day-to-Day Survival Skills—The Nitty-Gritty

Introduction

ART HAS ITS OWN CURRICULUM

Use varied approaches when you introduce a lesson. Through an early introduction to art, students learn to recognize and apply the elements and principles of art and design. They can develop an appreciation of artists in any culture. Art history, problem-solving, and skill building expectations are found in National and State Core Art Standards. Never lose sight of the simple joy that producing a work of art gives to most children. It gives them another way to express themselves and awakens imagination in them that no other discipline can.

RELATIONSHIPS WITH STUDENTS

Friendliness, caring, tolerance, and consistency are important attributes for teacher–student relationships. If you are relaxed and calm, and students know you love teaching them, they will recognize it. After you have presented a lesson, ask individuals in the class what the “steps” will be, or ask if they would like to share an idea related to the project. This helps to keep them involved and allows you to clarify any misunderstanding. Afterward, ask the students what they learned (if you write this on a poster board as they talk, their observations can be displayed with the artwork for viewers to see).

Sometimes it is good to be outside your classroom when students arrive—just chat with them when you get a chance. Be a good listener. It is often easy to pick up clues when a student is having a bad day, and sometimes paying a little extra attention may be something you can easily do during an art class to make it better.

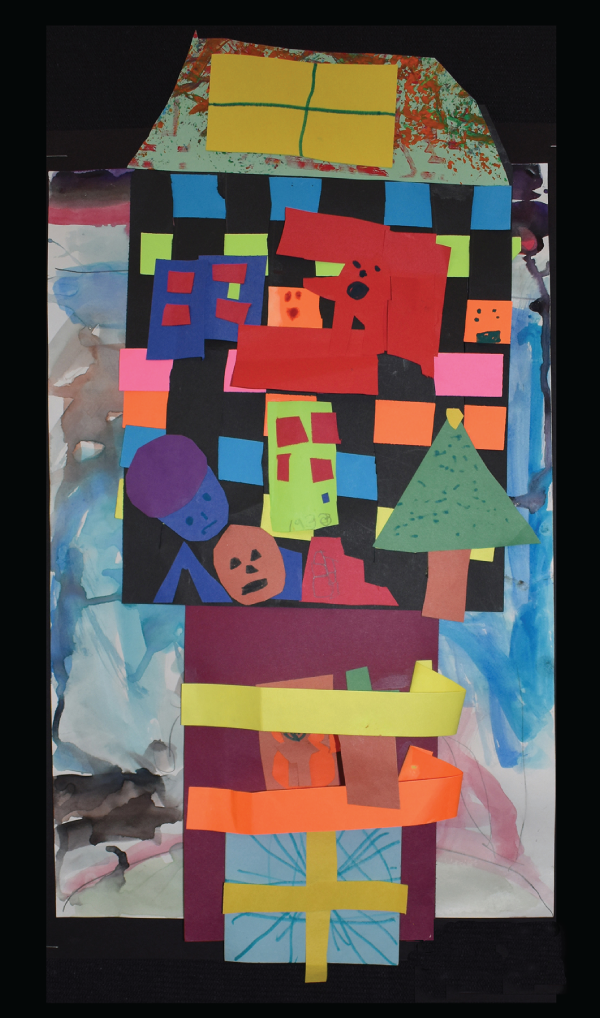

Figure 2.1 Collage and Watercolor, Yoel Lee, Grade 1, Chesterfield Elementary School, Rockwood School District, St. Louis County, Missouri. Art teacher, Julie Glossenger.

HAVE HIGH EXPECTATIONS

Few students will work on something any longer than they have to. You will do them a favor by not accepting casual, half-completed work. A project might become more interesting by introducing more than one medium. For example, a less-than-successful watercolor could be combined with other media in a collage. Or a less-than-perfect painting might benefit by outlining details with a silver oil pastel. In the student example shown here, the student included a placemat that was woven from the previous year to create an altogether new composition. Informed teachers are willing to experiment with new concepts in art education. Some projects might be further developed, for example, by introducing a new medium such as adding watercolor to a crayon drawing or combining a completed artwork within a collage. Just remember to give the students the chance to surprise you!

Setting Up Your Classroom

MAKE IT VISUALLY AMAZING!

By its very nature, the art room can be an exciting place to enter. Before the year begins, take time to make it appealing with colorful posters and paper in a variety of colors. Perhaps you've chosen to feature one artist or culture on a bulletin board. Other important items (rules, timelines, color wheel, art materials) can be added when you need them for a lesson and may become more meaningful to the students at that time. Make an effort from time to time to refresh the room by posting new visuals (and removing some that are tired).

Obviously, the tables and stools or chairs for your students come first. If space permits, it is better to have more tables and fewer seats at each table. See the section titled “TAB (Choice-Based Art Education)” in Chapter 1 for another way to set up your room.

AS FOR YOUR DESK

It can go into a corner anywhere. You should not plan on sitting at your desk during class time. You will be constantly circulating in the room. When you move around, students are free to ask you for help – a great chance to praise the work of every student at one time or another. You will soon find the best places to stand and watch classroom behaviors. Proximity! Much can be headed off simply by where you stand.

TECHNOLOGY IN YOUR ART ROOM

Many art teachers are supplied with a computer, which is likely best placed on your desk to protect it from spills, clay dust, etc. Another desirable item to have either on or near your desk is a document camera. This will allow you to project your examples, student examples, and demonstrations with media that will be easy for all students to see. Speakers for your computer will make short videos or music (which you access through your computer) more easily heard throughout the room. Since the computer, document camera, and speakers are interconnected, these items are suggested to be on or near your desk. The projector is often ceiling mounted to show onto a whiteboard, interactive board, or pull-down screen.

If you need assistance getting equipment to work together, call for technology help from your school or from the school district. Make yourself aware of how other schools in your district or neighboring districts are set up with technology, as you should fit into the norm. If you think your room is not equipped similarly to others, talk first to your principal and ask for suggestions on how to acquire the items you need. There are often separate budgets set aside for technology. If not, another possibility is to write a grant application. Even though it is time consuming, it could be well worth your efforts.

Students in your school may be assigned Chromebooks or iPads, or the school may have a cart of computers that can be wheeled into your room when needed. It is then feasible to offer your students digital art lessons. Again, the projector will allow you to introduce the lesson and show steps from your computer (see Chapter 10).

EQUIPMENT MANAGEMENT

Take care of equipment in order to keep from constantly replacing it. Simple supplies such as scissors and erasers are frequently borrowed and not returned, and you may find it necessary to “sign out” borrowed equipment. Cutting knives can be kept blade down in a Styrofoam block, but we recommend for safety purposes that these be kept in a locked cabinet and checked out only as needed. Never allow them to leave your classroom.

STUDENT NOTEBOOKS

Middle school and even elementary art teachers sometimes purchase pre-punched copy paper and clear plastic-fronted three-ring binders for their art students. These are normally kept in the room. Students are requested to date and keep their thumbnail sketches. Another option is for students to make a copy paper journal for entries, notes, sketches, handouts, homework, and small works-in-progress in their notebooks. The first project of the year can be a front cover for the notebook.

STORING ARTWORK

Works-in-progress are often wet and messy, and must go on a drying rack, the hall floor, or a corner of the room until they dry. When dry enough to handle, two-dimensional works can be stored in class drawers or class portfolios. Three-dimensional works can be placed in boxes or trash bags, identified with the classroom teacher's name.

MAINTAINING PORTFOLIOS

Make large portfolios of folded and stapled 28” × 44” tagboards for each class, labeling the portfolio with the teacher's name for each of your classes. Work can be kept in these portfolios in the art room until it is ready to be taken home or displayed. This allows you to see the progress that a student has made, and you are easily able to select work for displays and exhibitions. Alternatively, a cell phone or classroom digital camera may be used to record each student's work when it is complete. This digital record allows the student (and parents) to see progress and reinforces the value that you and students place on their artwork.

SIGNING WORK

Students may sign their work on the front, but show them how they can inconspicuously print or sign their names next to a subject (such as along an arm or leg of a figure) without detracting from the composition. Or they can use a variation of a color to sign on a lower corner in the front (e.g., use dark green on light green grass).

LABELS

Make labels with space for the student name, grade, art teacher, and school. Have these neatly cut, and always ready to attach to any artwork that is displayed. For a uniform display, have students fill them out with black ink from a Sharpie marker.

DISPLAYING STUDENT WORK OUTSIDE THE ART ROOM

Try to keep several examples of a project for end-of-year displays, making sure that you have at least one thing from every student. One way to let all students see that their work is valued is to display the work of every student, not selecting just a few of the “best.” If the artwork is arranged with the more eye-catching compositions on the outsides and near the middle, even so-so work takes on importance. It is also very effective to make a placard to place with a group of similar projects to explain what was learned (ask the students, they will tell you). Use available walls and counters around the school or in the library for display. Displays in community, school, or district art exhibits and websites, as well as state art exhibitions, all offer opportunities to showcase your students' work. One general guideline to keep in mind is that the farther away from the art room, the higher the quality of the work should be. Most artwork can be enhanced with matting, even if the display is as simple as centering the work on a colored piece of construction paper. Remember to always put a tag with the student's name on or beside the work.

CLEANUP

Many art rooms have a single sink. If at all possible, avoid having young students wash their brushes or hands at the sink. Younger students can put paint brushes in a tall container for later washing by an older student helper or the teacher. Sponges may be used by students to wipe tables, but some teachers prefer moistened wipes for hand and table washing. If students washed their hands, they can use the damp paper towel on which they've dried their hands to clean the table.

DISMISSAL

Give ample warning about the end of the period. Take advantage of every teaching minute you have, using the last five to do or talk about something special.

NEW ART MATERIALS

Vendors attend state and national conventions and have some of the finest art educators in the country demonstrating how to use new materials. Even young students can be told that they are using very special materials, and that care must be taken in putting them back in the box to help make them last. If they mistreat new boxes of materials, then these should be put away and the old ones brought back out.

RECYCLING

Art teachers are natural scavengers. They use things from nature and were into recycling long before it became fashionable. Notes sent home to parents often result in marvelous things being sent into the classes. Of course, you must be prepared to store all the donations or use them quickly. Clear plastic storage boxes with lids and stackable drawers can be labeled with marker on the front so students can locate their own supplies. Some towns have organized recycling centers for teachers, where, for a slight fee, out-throws from factories—such as foam sheeting, buttons, plastic yardage, lace, newsprint roll centers, fabric, centers from fabric bolts, carpet tubes, and so on—are available for teachers. If your town doesn't have one of these centers, why not get together a group of teachers (or parents) and organize one!

USE A SEATING CHART FOR ALL GRADE LEVELS

This will help both you and the students. Remind them that the purpose is to give each student a seat where they can produce their best work. Its intent is not necessarily to have friends sit together. Also remind them that seats will likely change according to what you observe works the best for their class.

DEVELOP A SIMPLE RULES CHART

State the rules positively and post in a prominent place in the room! Keep your rules simple and easily understood by all grade levels you will teach in the room. Be ready to discuss your rules with the class on the first day but know that you will have to bring them back up from time to time. Try not to change your classroom rules. Children thrive with routine. There is a comfort level in knowing that acceptable behaviors will not change. Year-after-year, your students quickly learn what your expectations are.

THINK ABOUT INCLUDING A CALMING CORNER

This is simply a small, somewhat secluded area where students can go if they feel they are about to lose self-control. It is best if only one student is in this spot at a time. Set a timer for 3 minutes. Provide quiet activities for the calming corner, such as some art books (they love books that show them how to draw something). The idea is to de-escalate the student. After 3 minutes, they should rejoin the class.

Fostering Creativity

Part of your job as an art teacher is to nurture a fertile ground for your students’ creativity.

- Think of what is normal, then encourage changing the normal.

- Give examples of “going outside the box.”

- Be the spark! Show enthusiasm and acceptance for a new spin on your directions.

- Offer suggestions to expand the student's thoughts.

INDIVIDUALISM AND PROBLEM SOLVING

Young people build on artistic concepts and skills by review and practice, gaining confidence each year. A blank piece of paper, a lump of clay, or a pile of recycled “treasures” would be intimidating to any artist, but the art teacher (and “liberated student”) sees fresh material as an opportunity to do an original, creative work of art.

ALLOW ENOUGH TIME FOR A PROJECT TO DEVELOP

If materials are simply placed in front of the student with no discussion, it is likely that it would take a long time for much to happen. Try to teach in a manner that will avoid a predictable outcome. If you know in advance what the end result will be, then every individual's work will be similar, and you haven't given the student the chance to consider possibilities and come up with a personal solution. Sometimes allowing a project to develop over several class periods gives students opportunities to develop an idea that will give a remarkable result.

NEVER DRAW ON A STUDENT'S WORK

If you want to show an individual how to do something, draw it with your finger or draw a suggested change on a piece of paper, then throw your paper away. If you draw directly on a student's artwork it is the same as telling them that their work isn't good enough.

BE FAIR TO ALL STUDENTS

Observe your interactions with all students from time to time to be sure you are being fair to everyone. Try not to allow needy students take a disproportionate share of your class time. All students are entitled to their share of your time—those to whom art comes easily, those to whom nothing comes easily, and those in the middle who may need help but rarely ask for it. If some students have an IEP (Individualized Education Plan) or IDEA/504 (Individuals with Disabilities Education Act/504), follow it exactly to provide a better classroom experience for the student.

QUIET THINKING TIME

When introducing a new lesson, have a quiet thinking interval for students to sketch and plan what they will do. Sometimes writing or drawing on copy paper helps. One colleague teaches students from kindergarten on up to make a preliminary pencil drawing for every project. A notebook allows them to keep track of their previous lessons.

PRAISE WHEN IT IS JUSTIFIED

Try to avoid simply telling a student the work is good. If you always say something is wonderful, it will lose its meaning. Instead, praise one aspect of the artwork. Point out something that is especially appealing, such as “You really made an effort to fill the page,” or “I notice that you varied the thickness of your lines,” or “I love how you used these two colors together.”

The Elements and Principles of Art

Art educators talk about the elements of art and principles of design as if artists had always based their work on them. These formal terms used to analyze art have come into use in the relatively recent past, and the terms may be totally unfamiliar in many parts of the world. Today, less emphasis is placed on the elements and principles in teaching, but they continue to offer a structure that bolsters art lessons in all media.

Work done by some contemporary artists looks as if it might have been done hundreds of years ago because art traditions have changed very little in that culture over the centuries. Designs were passed down through families or from artist to artist in a system of apprenticeship, or through copying existing artworks. In China, copying the work of an old master is considered a compliment to the master and the tradition. In African carvings and bronzes, stylistic traditions have continued for hundreds of years and might identify a particular region or cultural group. Artists instinctively understood how to create works of art that would be beautiful in their culture, even though these might appear “strange” to people from another culture who lack understanding of the tradition. Contemporary artists from some cultures might continue the tradition, incorporating familiar designs, whereas others show no evidence of a cultural heritage in their artwork.

MNEMONICS—REMEMBERING THE ELEMENTS AND PRINCIPLES OF ART

Art teachers often develop a mnemonic (pronounced newmonic)—words strung together that begin with the same first letter—to help students remember the elements and principles of art. Here are mnemonic examples developed by Parkway School District teachers Meg Classe, Peggy Dunsworth, and Marilyn Palmer.

National Coalition for Core Art Standards

The National Art Education Association (NAEA) has been working with the National Coalition for Core Art Standards (NCCAS) for some years to revise all arts standards, including visual arts and media arts standards.

Although state assessment systems by law annually test students in reading/language arts, mathematics, and science (because of the No Child Left Behind Act of 2001), fine arts are not yet required to be tested. If you live in the USA, check to see if yours is one of the many states that has elected to write their own grade-level expectations in fine arts.

Art educators can find current information at the following URL, which will take you to the NAEA website, where you can learn more about the NCCAS and find the publication that they issued in March 2018. The Standards are a process that guides educators in providing a unified quality arts education for students in Pre-K through high school.

https://www.arteducators.org/learn-tools/national-visual-arts-standards

CREATING

- Anchor Standard #1. Generate and conceptualize artistic ideas and work.

- Anchor Standard #2. Organize and develop artistic ideas and work.

- Anchor Standard #3. Refine and complete artistic work.

PRESENTING

- Anchor Standard #4. Select, analyze, and interpret artistic work for presentation.

- Anchor Standard #5. Develop and refine artistic techniques and work for presentation.

- Anchor Standard #6. Convey meaning through the presentation of artistic work.

RESPONDING

- Anchor Standard #7. Perceive and analyze artistic work.

- Anchor Standard #8. Interpret intent and meaning in artistic work.

- Anchor Standard #9. Apply criteria to evaluate artistic work.

CONNECTING

Anchor Standard #10. Synthesize and relate knowledge and personal experiences to make art.

Anchor Standard #11. Relate artistic ideas and works with societal, cultural, and historical context to deepen understanding.

The Standards in Action Planning Sheets that follow were developed by Dr. Marilyn Stewart, a member of the National Art Education Committee, which helped to develop the standards. Because of lack of space, these three grade levels were selected as examples.

Assessment

AUTHENTIC ASSESSMENT

The art teacher can offer authentic assessment (real evidence of real learning) by building assessment methods into the lesson or a unit, reflecting the relationship between lesson plan objectives and evaluation strategies. Students should be told what they are expected to learn, and instruction given with that in mind. The evaluation is then based on how well the students met the objectives. The assessment should be manageable and appropriate for the age group. Older students often do self-assessment.

PORTFOLIOS

A student portfolio may be started in the primary grades. As students advance, they may become more selective about what is kept in the portfolio. Portfolios record the creative process by including preliminary sketches, providing a way for teacher, parent, and student to evaluate continued growth. Personal discussion with students about their portfolios is ideal, but if this is not feasible, students can do a written self-evaluation about which they think is their best work, and why. Alternatively, a written comparison could be made between work done early in the year and later work.

JOURNALS OR SKETCHBOOKS, SELF-ASSESSMENT

Student journals (three-ring loose-leaf binders are excellent) give students the opportunity to react to art through writing and drawing. Middle school teacher Judy Cobillas of the Clayton School District, St. Louis County, had her students use their notebook–journals to include writing, sketches, and critiques of their own art and historical examples. A standard reflection page was photocopied for students to occasionally turn in, containing questions about their own work based on a medium or technique, and what the student was trying to show.

CRITIQUING STUDENT WORK

Discussion about student work-in-progress is very effective, especially if it is a lesson that continues another day. At the elementary level, students generally have art once a week. With a long time between classes, it helps bring the focus back to the objectives. Beginning the class period by showing exemplary student examples of various steps is very effective. Also, while they are working, stopping the class to look at a piece you hold up for all to see while you “brag on the artist” is a great motivator. Both techniques work well at all grade levels. This is another reason to never allow students to throw away their work. Tell them you may need it as an example for next year's students who might do the same project.

A shoulder-to-shoulder discussion is another way of handling a critique without taking too much class time. Without students getting out of their seats, they should work with someone sitting next to them to ask for improvement suggestions. This short activity only needs about a minute of class time and allows students to help each other.

A formal critique done with all students' work hanging on a wall is more time consuming, and therefore works best with grades 6–8. Since you and the students would try to talk about each piece of artwork, the students must have a longer attention span. It may work well with one class and not with another at the same grade level. As you work with your students, you will get a feel for what works best with each class.

RUBRIC OR SCORING GUIDE

There are many ways to assess student artwork. In general, it becomes more necessary at the middle school level to show how you arrive at the grade that you assign for grade reports.

Be sure to communicate well how points will be achieved as the lesson progresses. A self-evaluation before the teacher evaluation is another helpful tool to encourage students to reflect on their work.