In the middle of the 19th century, the SoHo district in London’s West End was not the trendy fashion, retail, and dining area that it is today. Once a pastoral setting of fields and farms, by the 1850s, “Soho had become an unsanitary place of cow-sheds, animal droppings, slaughterhouses, grease-boiling dens and primitive, decaying sewers.”1 London’s relatively new sewage system had not yet reached this part of town, and many cesspools were overflowing into basements and cellars.

Paul-Gustave Doré, Over London–by Rail, c. 1870, engraving. From London: A Pilgrimage by Paul-Gustave Doré and Blanchard Jerrold (1872).

Today we understand that such conditions breed germs and infections, but this was decades before germ theory became widely accepted. At the time, though none of the residents knew it, SoHo was a perfect breeding ground for killer bacteria.

THE 1854 CHOLERA OUTBREAK

On August 31, 1854, residents of SoHo started dying. Only three days later, 127 people had already succumbed to the cholera outbreak.2 The death toll would reach over 600 before it ended. What was the cause? Why and how were all of these people contracting cholera?

A prominent and well-respected doctor named John Snow wanted to find out. By this time, Snow was a member of the Royal College of Physicians and a government advisor who had spent several years studying cholera. Snow was a skeptic of the widely accepted miasma theory, which posited that diseases were caused by coming into contact with polluted, or “bad,” air. Instead, Snow had begun to believe that small biological organisms called germs were the cause of diseases like cholera.3

Based on his prior research, he suspected water was the most likely source. So Snow did something simple and obvious—he went to SoHo and began talking to the remaining residents, asking them questions about life in the area and about their water consumption habits. He then compiled and analyzed the results.

From those interviews, Snow deduced that the source of the cholera outbreak was probably the water pump located on Broad Street in the center of the neighborhood. He approached the town council with his evidence, the council shut down the pump on September 8, and the outbreak ended.

Once the outbreak was contained, Snow wanted to ensure that each case of cholera during the outbreak could be traced back to the Broad Street pump. So he plotted all of the cholera deaths on a map of the neighborhood. For all but 10 of the victims, the Broad Street pump was the closest available water source, and of those 10, Snow discovered through interviews how each had made occasional use of the Broad Street pump. In Snow’s words, “the result of the inquiry, then, is that there has been no particular outbreak or prevalence of cholera in this part of London except among the persons who were in the habit of drinking the water of the above-mentioned pump well.”4

Once the pump was dismantled, Snow took it back to his laboratory for further investigation, but he was unable to identify any chemical or biological causes for the cholera. (The cause was eventually identified as a breach in a cesspool located only feet away from the Broad Street pump containing the diaper of an infant who had died from cholera.) Still, without any supporting laboratory evidence—without any absolute “proof”—Snow was able to determine that the SoHo residents who contracted cholera did so by drinking water from the Broad Street pump. He did this solely by assembling, analyzing, and drawing scientifically based conclusions from a large amount of accurate data.

Dr. John Snow’s map of cholera fatalities (black dots) during the 1854 London outbreak, showing the locations of pumps (X), with the Broad Street pump in the center.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Over the course of his career-long effort to identify the source of cholera and make the environment healthier for human beings, Snow pioneered many scientific research and analytical techniques, solving multiple problems that were impossible to answer in a laboratory. In so doing, Snow developed a whole new branch of science—epidemiology.

Epidemiology is the science of studying patterns, causes, and effects of health and disease in a given population. It enables us to research and answer questions that would otherwise be immoral or impossible to research in a laboratory. Today, epidemiology is a critical component of both modern science and public health, providing key insights on a huge number of important questions.

Laboratory studies (or experimental science), which is able to isolate variables, can sometimes prove causation—that one thing causes another. If we expose DNA to EMF, we see an increase in strand breaks. This indicates that EMF is a cause of DNA strand breaks. If others repeat the experiment and get the same results, we have repeatable scientific evidence that EMF causes strand-break damage in DNA. This is what we mean by scientific proof.

Because it works differently than traditional laboratory science, epidemiology cannot prove causal relationships. Instead, epidemiology relies on the analysis of statistical data to establish correlations, or the relationship between two or more sets of data. For example, by examining the drinking habits of those infected during the 1854 outbreak, Snow demonstrated that there was a high correlation between drinking from the Broad Street pump and contracting cholera. This did not prove that drinking the water caused cholera; he demonstrated that the acts were correlated.

This type of research does not prove causation, but it is a powerful, scientifically valid tool to analyze data and come to an improved understanding of the world around us. Despite the fact that epidemiology studies can show only correlations and cannot prove causality, scientists, physicians, public health experts, and people in general tend to rely heavily on epidemiological studies for guidance on public health issues. Cancers, like other diseases including Alzheimer’s, take a long time to develop—too long to run experiments in a laboratory. Scientists have used the tools of epidemiology to demonstrate, for instance, the increased correlation of smoking tobacco and the incidence of lung cancer. In fact, the government warnings against smoking were first issued based largely on epidemiological evidence, decades before the causal relationship between tobacco smoking and lung cancer was established.

When we approach the question of the health effects of EMF on human beings, we must similarly rely heavily on the tools of epidemiology and the examination of larger populations of individuals.

CELL PHONES AND CANCER

Epidemiological studies have begun to show us that low-frequency, non-ionizing electromagnetic radiation correlates with cancer. Exposure to even low-frequency, non-ionizing EMF (including radiation from cell phones and WiFi devices), as well as extremely low–frequency, non-ionizing electromagnetic radiation (such as comes from power lines), may be carcinogenic. We see this in a large number of epidemiological studies that demonstrate a correlation between specific types of exposure to EM radiation and the incidence of specific types of cancer in large populations.

In recent years, a significant share of the research into EMF and cancer has investigated the impact of cell phone radiation. In 2009, the Journal of Clinical Oncology published the findings of a team of seven scientists, who reviewed 23 epidemiological studies on the link between cell phone use and cancer. The team concluded that

although as a whole the data varied, among the 10 higher quality studies, we found a harmful association between phone use and tumor risk. The lower quality studies, which failed to meet scientific best practices, were primarily industry funded.

The 13 studies that investigated cell phone use for 10 or more years found a significant harmful association with tumor risk, especially for brain tumors, giving us ample reason for concern about long-term use.5

The higher-quality studies demonstrated a positive correlation between cell phone use and cancer, and the longer-term studies demonstrated an even stronger link. The point about length of exposure is a very important one. Cancers do not form overnight. In almost all cases, cancerous tumors take many years or decades to form and metastasize, and in many cases they result from extended exposure to carcinogenic agents. These results suggest that, as with tobacco smoke, cancer may be a long-term result based on repeated and/or extended exposures to EM radiation sources. It is for this reason that studies that conclude there is no link between cell phones or other sources of EMF and increased rates of cancer based on short-term exposure and evaluation are highly suspect.

On the contrary, there is a strong and increasing body of evidence that demonstrates the relationship between EMF exposure and cancerous outcomes. A 2007 review of 16 studies on this subject found that the studies all demonstrated increased risk of brain tumors known as glioma and acoustic neuroma (cancers that develop on the nerves associated with hearing and balance that run along the side of the face) among cell phone users.6 Compiling the data across studies for 10 years and greater, the risk of developing an ipsilateral glioma tumor (a tumor on the same side of the head as the cell phone is used) was elevated 240%. The incidence of ipsilateral tumors reinforces the connection between radiation and cancer, as these tumors develop in the precise area where exposure to cell phone radiation has been most intense.

Note that the 240% increased risk is an average across studies, with some studies demonstrating much higher risks. In one of the cited studies, researchers concluded that there is an “increased risk of acoustic neuroma associated with mobile phone use of at least 10 years’ duration,” with a 90% increased risk for the auditory nerve cancer and an astounding 390% greater risk when restricting to ipsilateral use.7

This study also found that there was not an increased risk in those who used cell phones for fewer than 10 years. However, while this may be true for adults, other research indicates that children are much more sensitive to shorter exposures. In 2009, Dr. Lennart Hardell reported that children who begin using mobile phones at ages younger than 20 have a 520% elevated risk of developing glioma—even after just one year of use (this is compared to a 140% elevated risk across all ages).8

Other recent research out of Israel reinforces these findings. Israelis are heavy cell phone users who, on average, increased cell phone usage six-fold between 1997 and 2006.9 As Dr. Siegal Sadetzki of Tel Aviv University explains, this population provides an excellent context in which to examine the potential for low-frequency EMF to cause cancer in human populations.10 In 2008, Sadetzki and her colleagues published a study in the American Journal of Epidemiology that concluded that heavy cell phone users (those who use cell phones at least 22 hours a month) were at least 50% more likely to develop cancer of the parotid gland (one of the salivary glands) than those who never or rarely used mobile phones. Sadetzki’s results, consistent with Hardell’s findings, demonstrated a higher incidence among those with ipsilateral use, reinforcing the link between the use of cell phones and the occurrence of cancer.11 Sadetzki concludes that “this unique population has given us an indication that cell phone use is associated with cancer.”12

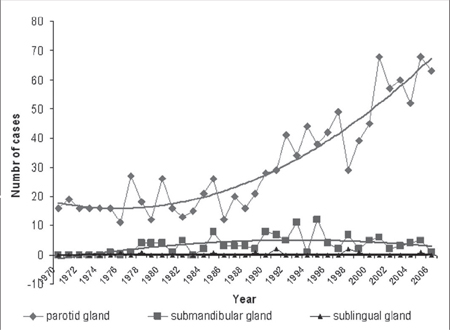

Given Sadetzki’s findings on the link between cell phone radiation and parotid cancer and the popularity of cell phones in Israel, one would expect to see a notable increase in cancer of that type, corresponding to the rollout of this technology. And this is precisely what a review of the data demonstrates. A review of deaths between 1970 and 2006 from Israel’s National Cancer Registry found that “the total number of parotid gland cancers in Israel increased 4-fold from 1970 to 2006 (from 16 to 64 cases per year), whereas other major salivary gland cancers remained stable.”13

This result can be thought of as a control experiment. During this period, when parotid gland cancer was increasing in Israel along with cell phone use, cancer of the submandibular and sublingual glands (shielded from cell phone radiation by the jaw bone and tongue, respectively) remained constant. This is illustrated in the figure below, which plots the incidence of parotid (♦), submandibular (■), and sublingual (▲) gland cancers between 1970 and 2006.

TOWERS

In studying the cancer and health risks of cell phones, it’s important to remember that there is also radiation from the towers and antennas needed to transmit the signals. Whereas use of a cell phone is discretionary and individuals can opt to minimize or eliminate their exposure to radiation from mobile devices, these towers are always on and broadcasting, emitting RF and MW into the environment, and radiating everyone within range—whether or not they use a cell phone. This, of course, includes the many infants and young children who are not yet cell phone users. People have no choice as to whether or not to be exposed to this radiation. In a sense, tower radiation can be viewed as the cell phone equivalent of second-hand smoke.

Industry and related organizations acknowledge the presence of RF from these towers but they maintain that public exposure to the radio waves from cell phone tower antennas is slight.14 For example, they point out that the antennas are mounted high above ground level with the result that the RF loses much of its intensity before it reaches people. Despite these claims, several recent studies indicate an increase in cancer associated with proximity to cell towers. And the closer one is to the tower, the greater the risk of developing cancer. In fact, some people live in apartment buildings with these transmission towers immediately above, on the roof, and as we can see from the example of England’s Tower of Doom, the results can be tragic.

The Tower of Doom is a pair of masts, or towers, owned by the British firms Vodafone and Orange that were erected on top of an apartment building in 1994. In the following years, the local residents, and particularly the dwellers of the apartments in the buildings directly under the masts, began noticing an increased incidence of negative health effects, including cancer, which they attributed to the towers. Among the residents of the building who were affected are John Llewellin, who died of bowel cancer; Barbara Wood, Joyce Davies, and Hazel Frape, who all died of breast cancer; Barbara Watts and Phyllis Smith who both developed breast cancer; and Bernice Mitchell who developed uterine cancer. The cancer rate on the top floor of the apartment building was 10 times higher than the national average, with inhabitants of five of the eight apartments becoming ill. This was, in fact, a cluster event (several cases of cancer in the same location), with seven documented cases of cancer in a group of 110 residents. Eventually, after years of public pressure and action, Orange agreed to remove their tower. Vodafone, in contrast, has not, and the South Gloucestershire Council remains unable to force removal because current safety standards do not indicate that cell phone tower radiation is dangerous.15

A 2011 review of the research published on the question of long-term exposure to low-intensity MW radiation (such as that to which you may be exposed by nearby towers) noted demonstrable carcinogenic effects, which typically manifested after extended exposure of 10 years or more. Unfortunately, these low levels of MW radiation are well within the ICNIRP (the International Commission for Non-Ionizing Radiation Protection, of the World Health Organization) safety standards (discussed in chapter 10).16 On the specific question of radiation from cell towers, this review noted that even one year of exposure led to a “dramatic” increase in cancers in nearby residents. One study compared cancer cases among people living up to 400 meters (less than a quarter of a mile) from a base transmitting station and people living farther away. After ten years, the group close to the base station had over three times the rate of cancer relative to those living at a greater distance.17

Similar findings have been reported in studies in Brazil, where the greatest accumulated cancer incidence was among those exposed to power densities as high as 40.78 µW/cm2. The reported incidence was 5.83 per 1,000. Those farther away who were exposed to a power density of 0.04 µW/cm2 (levels 1,000 times lower than the group with the highest exposure) had a lower cancer incidence of 2.05 per 1,000.18 These studies, and others like them, indicate that towers are a significant component in the risks associated with cell phones.

NOT JUST CELL PHONES

So far, we’ve discussed the possible health risks of cell phones and their associated technology. But cell phones are only one of many devices that produce and transmit radio-frequency EMF. The modern world is pervaded by “EMF producers”—microwave ovens, computers, radio and television broadcasting, to name just a few—and they have a wide range of characteristics.

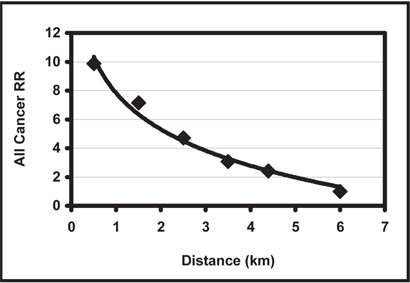

Dr. Neil Cherry was an environmental scientist from New Zealand who spent a good deal of time researching the questions of the health effects of electromagnetic radiation. In one study, Dr. Cherry investigated the health risks associated with television and FM radio broadcasting antennas—which broadcast EMF at a lower frequency than cell phones and cell phone towers. As part of his study, Cherry examined the incidence of childhood cancers over half a century among those who lived close to the Sutro Tower broadcasting antennas in San Francisco between the years 1937 and 1988. By plotting the occurrence of 123 cases of cancer among 50,686 children, he demonstrated that living closer to the tower correlated with a higher incidence of childhood cancer and that the risk for such cancer dropped significantly with increased distance from the antennas. Overall, the incidence of childhood cancer was quite high—especially considering that the measured EMF at three kilometers (where the relative risk was about six) was approximately a thousand times lower than the currently accepted safe level.19 Yes, you read that correctly! The relative risk is high (~6) even at a power density that is approximately a thousand times lower than the currently accepted safe level.

Sutro Tower data, 1937-88. The relative risk (RR) of cancer vs. the distance in kilometers from the antenna. Neil Cherry PhD, “Childhood Cancer in the Vicinity of the Sutro Tower, San Francisco,” Human Sciences Department, Lincoln University, September 19, 2002.

Dr. Orjan Hallberg of the Karolinska Institute in Sweden published a series of studies between 2002 and 2008 that examined the carcinogenicity of FM transmitters. Hallberg noted that rates of melanoma in Sweden and other Nordic countries had been on the rise since 1960—in contrast to the previous 50 years in which rates of melanoma incidence had been stable. Hallberg hypothesized that FM transmitters (which had been introduced in the Nordic countries in the 1950s) might be involved. His studies first demonstrated that rates of melanoma increased with the length of exposure to FM-frequency EMF radiation, from which he concluded that “melanoma is associated with exposure to FM broadcasting.”20 He pinpointed 1955 as the point in time when these stresses were introduced into the environment21 and developed a model to explain the increasing incidence.22 He subsequently released a model explaining that “reduced efficiency of the cell-repairing mechanisms [such as those we discussed in the previous chapter] is capable of explaining the increasing trends of melanoma incidence that we have been noticing since the mid-20th century.”23

Adding evidence to support his conclusions, Hallberg noted that whereas in prior generations melanomas were generally limited to those areas exposed to the sun, increasingly such cancers were being found all over the body (as would be expected if these cancers were caused by exposure to EMR, rather than solar radiation).24

As with other studies we’ve seen, Hallberg demonstrated a link between the degree of EMF exposure and the incidence of cancer, finding that “those who had four FM-radio or TV towers covering their residential area are more than twice as likely [to develop melanoma] as those who had one.” This is what is known as a dose-response relationship, in which an increased dose yields an increased response. Data that demonstrates this dose-response relationship is generally considered more reliable, as a stronger exposure leads to a stronger effect, increasing the correlation between exposure and effect that the data demonstrates.

POWER LINES

Communication towers are not the only technical infrastructure on which television, FM radio, and cell phones rely. These and other electronic devices are similarly dependent on access to electrical power and that access comes via power lines. The lines transmit the power generated at the main power stations and bring it to substations for distribution in neighborhoods.

In a few locations, these power lines are placed underground, thus reducing exposures at ground level. Because underground installation of power lines is more expensive, only a few urban centers such as New York City and San Diego have buried lines. One 2005 study concluded, for example, that the cost of converting aboveground power lines to underground in Virginia would total $800,000 per mile, or $83.3 billion.25 More typically, power lines run above ground, positioned to affect much wider areas.

The voltage (the force driving the electric current) is often so strong that you can hear a crackling noise coming from the big cylindrical transformers. Electric power transmission occurs at high voltage and is accompanied by strong magnetic and electric fields. Here, once again, the epidemiological evidence is that exposure to these sources of low and extremely-low-frequency non-ionizing EMF is associated with increased rates of cancer.

All of this power comes from the power grid. While this grid is ubiquitous in the United States today, it was rolled out in different parts of the country at different times—generally, urban areas preceded rural regions and the northern United States preceded the South. By examining official archives and death records across these different regions from different periods of time, Dr. Sam Milham was able to show how increases in the death rate correlated with the onset of electrification, independent of where it occurred in the country. In one case, building upon existing, accepted research that childhood leukemia showed a peak incidence in children three to four years old,26 Milham and his colleague Eric Ossiander published a study showing that the appearance of this characteristic peak correlated with the introduction of electrification. In other words, the trend of childhood leukemia developing at a certain age is a modern one, which followed the introduction of the power grid, and this peak does not exist in unelectrified regions, such as sub-Saharan Africa.

While the entire power grid generates ELF radiation, high voltage power lines generate much stronger ELF fields than the power lines that run to your home. The EMF levels radiated by such lines are particularly dangerous. This link between EMF radiation from power lines and childhood leukemia was pointed out in 1979 by Dr. Nancy Wertheimer and Ed Leeper, who studied the possible carcinogenic effects of exposure to EMF from power lines in certain homes in Colorado. They concluded that growing up in a home surrounded by such high voltage electrical cables was, in fact, associated with an increased incidence of childhood leukemia. “The finding was strongest for children who had spent their entire lives at the same address, and it appeared to be dose-related.” They did not reach a conclusion as to why this correlation exists, but did mention “AC magnetic fields” as one potential reason.27

These findings and those of many other similar studies led the World Health Organization (WHO) in 2002 to include ELF (power-frequency EMF) among the possible causes of childhood leukemia.28 (WHO gave a similar evaluation regarding radio-frequency EMF and cancer in 2011,29 again relying heavily on information from epidemiology studies. These two decisions, warning of the possible health effects of EMF, cover almost all frequencies in the non-ionizing range of electromagnetic radiation.)

Some scientists previously believed EM radiation could only damage humans if the radiation was sufficiently intense to cause heating of the tissues. This theory, which is often referred to as the thermal criterion, has now been roundly discredited by many studies in which biological effects have been observed at intensities far too low to cause any measurable heating effect.

While cancer is a serious condition, it is just one set of human diseases that are, in many cases, caused by environmental stresses. If a force in the environment is strong enough to potentially cause cancer, then that force is also powerful enough to cause many other types of damage. In the next chapter, we’ll examine some of the other known health effects of electromagnetic radiation.