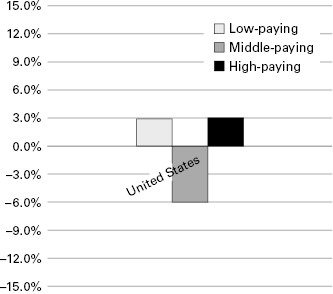

Figure 4 Change in occupational employment shares in low-, middle-, and high-wage occupations in the United States, 1993–2010

Source: Autor and Dorn 2013

President Nixon won the election in 1968 with the aid of a Southern Strategy focusing on regional racial tensions and the history of segregation. The Southern Strategy appealed to white Southerners angered by the threat to their power from the Civil Rights Movement and the expansion of the franchise. They were the heirs of slave owners who resorted to Jim Crow policies after Reconstruction ended to preserve their political power. Their policy was to maintain African Americans in the South in a subordinate position.1

The low-wage sector—like the FTE sector—was born in 1971 as President Nixon replaced Johnson’s War on Poverty with a new War on Drugs and appointed Lewis Powell to the Supreme Court. As the War on Drugs expanded in subsequent decades, it was enforced far more strongly for African Americans than for whites, becoming, in Alexander’s widely used term, the “New Jim Crow,” revamping and renewing the racist intent of the repressive old anti-black Jim Crow laws that followed Reconstruction in the South. And Nixon’s appointment of Powell, author of the memorandum for the Chamber of Commerce described in chapter 2, unified the class interest of Powell with the race interest of white Southerners in a Southern Strategy. Powell was presented as a moderate compared to Rehnquist—appointed to the Supreme Court at the same time—but Powell was part of Nixon’s Southern Strategy. Nixon “told Powell of his responsibility to the South, to the Supreme Court, and to the country,” in that order. Powell’s Supreme Court votes expanded Nixon’s Southern Strategy into national policies.2

This expansion was in part a response to the massive movement north of African Americans in the previous decades. The Great Migration, as it is known, started in the First World War when immigration was cut off and the demand for American war matériel grew. Business owners were eager to expand production if they could find workers to operate their factories. African Americans moved north to take these jobs, and businessmen were happy to have American workers instead of more European immigrants. The Great Migration continued until 1970 when the events described here began. People in the North found by then that blacks were in their cities and competing with them for jobs.

Rural people sold food to cities in the Lewis model; members of the low-wage sector typically sell services to the FTE sector in this modern reincarnation of the model. They work in fast-food restaurants and clean hospitals and hotels. They drive people around as needed, transport items in factories and stores, work in nonunionized industries and engage in other similar activities that vary too much for robots to take over. Low wages are the result of decreased labor demand coming from improving technology and increased supply coming from globalization in the varied forms of trade, immigration, and moving production offshore.

These varied forces resulted in a change in the demand for specific jobs that created an “hourglass” job profile, as shown in figure 4. Jobs are arranged by wages in the figure, and it can be seen that the jobs in the middle of the range have been disappearing. The number of these jobs fell by 6 percent between 1993 and 2010, while jobs with higher and lower wages rose. This trend has split the American labor market into a low-wage part and a higher-wage part. The division marks the difference between the low-wage sector and the FTE sector of the higher-paid workers. This figure helps explain the decline in the middle class shown in figure 1 by pointing to the changing nature of jobs.

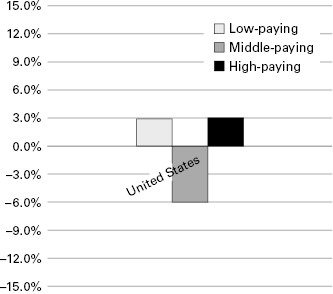

Figure 4 Change in occupational employment shares in low-, middle-, and high-wage occupations in the United States, 1993–2010

Source: Autor and Dorn 2013

Low-wage workers are laborers and service workers. Middle-wage workers are clerks, operators, and assemblers. Highly paid workers are professionals and managers. A college education is needed to get hired into the top group. It may also be needed for some middle-wage jobs, but these kinds of jobs are disappearing. Lower-paying jobs barely allow workers to maintain the life style they grew up expecting. They do not provide enough income for people to save for retirement, which seems farther away than many current needs. The low-wage sector has very little impact on the progress of the FTE sector.

Figure 4 often is seen as the result of technological change, but technology is only part of the story. Several causes can be distinguished, and they can be divided into domestic and international. All of them are results of decisions made in the nascent FTE sector. Advances in technology and electronics were promoted by government—primarily military—spending. The growing interest in finance shaped firms and industries. Globalization was accelerated by FTE policies opening international capital markets, promoting American foreign investment and American economic influence.

The development of computers in America was an important part of the growth of the FTE sector. Computer capital increasingly substitutes for labor in routine tasks, that is, tasks that can be accomplished by following explicit rules. These factory jobs were the basis of unions in the twentieth century. They also attracted workers in the Great Migration that brought African Americans from the rural South to the urban North. The migration ended in the economic confusion of the 1970s and left the new Northern urban residents scrambling for good jobs as the nature of work changed.

Computers are less able to deal with nonroutine tasks that require problem solving and involve complex and creative thinking, and those that require individual attention to specific people or places. Those jobs can be grouped into professional activities paying well and service jobs paying poorly. The former, well-educated jobs are in the FTE sector. The latter make up the low-wage sector.3

The growth of finance has added to problems facing workers by changing the boundaries of companies. In the early twentieth century, a lot of service jobs were performed within large companies. Cleaners, gardeners, drivers, and similar helpers were included on the company payroll. The service workers who worked for large companies tended to be paid more than those that worked in smaller companies, preserving equity among the workers at the large companies.4

But as finance expanded in the late 1970s, companies were encouraged to specialize in their core activities, that is, the activities that they were known and patronized for. This would increase their value on the stock market, and outside firms and services could be hired to do menial jobs. The same computers that reduced factory jobs also made it easier to create instructions for service jobs and to monitor them. The company supervisor was replaced by a contract with a separate company that monitored workers. For example, most hotel employees used to work for the hotels they worked in. Today, over 80 percent of a hotel’s employees are hired and supervised by a separate management company.5

This change in business organization can be accomplished in several ways, through subcontracting, franchising, and supply chains. These are different legal forms, but they all change the relationship between wages and companies. Before, companies and workers considered the equity of the wages that were paid. With all of these forms, wages have been supplanted by prices—the price of hiring the subcontractors and labor suppliers. There may be several tiers between a specific worker and the company where he or she works.

Several conditions are needed to make this new arrangement advantageous. Subcontractors may want to bid low for a service contract, while the parent firm is interested more in the quality of the work. The interests of the subcontractor need to be aligned with those of the parent firm. The alignment can be helped by increased monitoring of the workers, which has become cheaper as a result of the same technology that reduced factory jobs. Tasks need to be precisely defined, and there are now various electronics devices that can monitor individual actions. Parent companies want to avoid being held up by subcontractors who have captured spots in production plans. They seek to hire subcontractors in competitive markets where alternatives are readily available.

These new arrangements work for the company’s benefit, but not for the workers’ benefit. Wages from the parent company have been replaced by contract prices with companies. The equity considerations that helped workers before are gone. And since the workers are now hired by competitive subcontractors, their wages are compared with the wages of other people doing similar work rather than with the varied employees of the firm. There is no job tenure, no pension plan, and only relentless competitive pressure from the competition of other workers.

The shift from paying wages to hiring subcontractors is a momentous change in the place of workers in a business enterprise. When workers were wage earners, there was a social component to their work. Workers saw themselves as a group, and being a member of a stable group fostered morale. Most successful firms gain from the identification of workers with the firm and the extra care and effort that produces. When workers are hired instead by a competitive service company, they have no identification with the parent firm. They have low morale and will not exert extra effort for the parent company’s benefit. Intrusive monitoring replaces morale, and antagonism replaces cooperation.

The increasing role of independent contractors for the low-wage sector can be seen in the switch from consumers using taxi services to using Uber and other computer-based drivers. Uber recently settled a class-action suit by its drivers by paying them a bit more, but continuing to categorize them as independent contractors. And the bargaining power of these independent contractors will fall if Uber replaces them with driverless cars. Drivers now find their way with the aid of Uber maps on their smartphones; driverless cars can use the same maps once they learn how to drive in traffic.6

There also has been a sharp reduction in competition among large companies in America due partly to the growth of network effects and partly to a relaxation of antitrust standards for mergers. The reduction in competition is quite widespread, ranging from Apple and Microsoft in networks to agricultural businesses and wireless communication. The first effect is to raise prices to obtain monopoly rents. This reduces the value of poor people’s wages. A second effect is to reduce the competition for workers between companies, which directly affects wages. And the growing monopolists may not be as innovative as many independent and rivalrous companies, affecting the long-run growth of the economy.7

The growth of finance is reducing competition between firms even more in an indirect way—from the growth of mutual funds. Companies hold reserves for their employees’ pensions in mutual funds, and people do the same for their own reserves. Large mutual funds own shares in several firms in an industry and reduce competition between firms through this channel. Firms that are cooperating do not hire people from their fellow firms. The cooperating firms also present a united face to the companies who supply their labor, not allowing competition between them to raise wages. In addition to holding down wages, they also reduce competition in their product markets and raise prices from a competitive level. Worker’s real wages suffer both from low wages and high prices.8

Competition from new immigrants increased the pressure on wages. A steady stream of migrants came from Latin America in recent decades in search of better jobs. American political and military intervention in Central America stimulated immigration to the United States, since this country has not hesitated to depose Central American leaders who were unfriendly to American businesses. The resulting turmoil diminished national economies in Central America, and emigration northward was an appealing alternative to limited options at home. There were better jobs available in the United States, and conditions at home often were dangerous and even deadly.9

As technology decreased the demand for labor within factories and finance reduced direct employment by other large firms, foreign competition reduced the number of factories. The massive inflow of Japanese and then Chinese products reduced the demand for American manufactures at the same time that computers changed the nature of factory work. Japanese cars in the 1980s and an abundance of Chinese consumer goods in the 1990s changed the composition of labor demand in the United States. Manufacturing jobs in the United States fell particularly fast after 2000 when the United States eliminated future tariff rises for Chinese goods. Curiously, this major economic adjustment had very little impact on real earnings, as shown in figure 2.10

These imports resulted from the policies of these Asian countries to use low exchange rates to promote exports and economic growth. Just as Britain and Germany expanded industrial exports in the late nineteenth century, these new industrial powers promoted exports to increase their growth a century later. The gyrations of the emerging FTE sector in the 1970s and 1980s described in chapter 2 changed exchange rates as well as domestic prices.

Finally, improved capital mobility coming from the removal of Bretton Woods capital controls allowed American firms to expand production in industrializing countries. These firms used their offshore production in bargaining with their workers. American workers were told they had to accept lower wages in order to maintain their jobs. These threats produced labor unrest, and the government increasingly favored employers as deregulation spread. Unions declined in membership and power.

As a result of improving technology, changing business organizations, imports, immigration, and threats of offshore investments, American wages today are kept down as shown in figure 2. The members of the low-wage sector find themselves in a global labor market, competing for jobs with workers who live on the other side of the world. The effects often are indirect, but they are no less potent for being distant. The cost of transportation is decreasing; even perishable products like flowers and fish are brought from far away. And the decline of tariffs and other barriers to trade mean that governments increasingly open up their economies—and therefore national labor markets—to world influences.11

The constancy of real wages since 1970 has had effects in other measures of well-being as well. As wages did not rise with national income, the share of labor income in national income fell. The “labor share,” as it is often known, was widely assumed to be a constant of economic growth before 1970. Now we know it can change, and we know that it has decreased as a result of continuing low wages.12

In addition, mortality among members of the low-wage sector increased relative to mortality in the FTE sector. The result is that members of the FTE sector now live longer than those in the low-wage sector. This has implications for the social programs discussed further in chapter 12. But even with this basic information, it is clear that the argument that retirement should come later since people live longer is incorrect. Members of the FTE sector live longer, but people who need Social Security or other forms of retirement income are not living longer.13

The costs of international trade described here appear to undercut the theory that assures us that trade benefits all countries. The problem is that increased trade has uneven effects in each country; there are winners and losers. The theory of international trade tells us that winners gain more than losers lose, and that winners can compensate losers for their losses and still come out ahead. The theory is fine, but compensation needs to be paid in order for the losers—low-wage workers in this case—to be happy with increased trade. The failure of public policy to take account of the full theory undermines the popularity of globalization.

For example, under competition from foreign auto manufacturers and “transplants” (domestic producers of foreign-owned companies), GM implemented wage cuts in its 2009 bailout and bankruptcy: “Under agreement with the United Autoworkers union, the two-tier wage system was expanded, with wages for new hires cut to about half of the $29 per hour that longtime union members earned (although these wages were then raised to $17 an hour in 2011). Defined benefit pensions were eliminated for new hires and replaced with 401(k) plans. Overall wage and benefit costs at Chrysler and GM were brought down to be roughly in line with those at Honda and Toyota plants operating in the United States.”14

The union was not broken, but it clearly was unable to resist the pressures put upon it. It was not able to resist having new auto workers paid only as much as those at the mostly Southern and nonunion Honda and Toyota plants. Workers earning $17 an hour earn only about $35,000 a year. In addition, these jobs are being replaced by computers and robots as shown in figure 4, and there will not be many new ones. The few new auto workers will find themselves in the low-wage sector. Their earnings are small. Yet they are expected to set aside some of these inadequate earnings to save for their retirement in their new 401(k) plans. The incomes of low-wage sector members simply are not large enough for them to do so. A recent report on the economic well-being of households found that 40 percent of nonretirees “have given little or no thought to financial planning for retirement.”15

The decline of manufacturing noted in the FTE sector also had strong geographic effects on the low-wage sector. The growth of Japan and China accelerated the decline of American manufacturing and the demand for unskilled labor in and around factories. Industrial cities found that people were less mobile than jobs, and urban prosperity was replaced by urban joblessness. Black workers moved to Northern cities to find jobs in the Great Migration, only to find that the jobs had disappeared.

The Great Migration, which as noted earlier ended in 1970, did not lead to integrated housing in the North. As soon as Southern black workers appeared in Northern cities, white families began to move out of the cities. White flight was responsible for one-half of the increase in segregation in the 1930s. Prosperous white urban residents continued to leave cities for the suburbs after the Second World War, avoiding newly integrated schools. They were encouraged by the GI Bill and other federal policies that provided generous mortgages for suburban houses and highways for suburbanites to drive to work. Pervasive redlining that denied loans to people in urban areas restricted a comparable mortgage stimulus in the cities, and funding for aging urban transportation systems declined. Home ownership and access to jobs became harder in the city. There is clear evidence of neighborhood tipping, that is, a rapid transition to a very high minority share in a census tract once the minority share reached a threshold varying from 5 percent to 20 percent minority.16

White urban workers were replaced by black migrants from the South, aggravating the competition for scarce jobs in the cities. Wages for less-skilled workers declined, and urban unemployment grew. William J. Wilson observed twenty years ago, “Concentrated poverty is positively associated with joblessness.” And the public face of the low-wage sector is black. This merging of class and race fed into political decisions that expanded the Southern Strategy into a national one.17

Andrew Cherlin describes urban life in the low-wage sector even for working families as the result of casualization. Work is casual, short-term, not contractual, and unregulated. Family life is similarly casual with low marriage rates even among couples living together and having children. “Casualization, disengagement, rootlessness: these are the descriptors that seem apt” when describing the lives of less-educated young adults. “This situation stands in sharp contrast to the greater stability of the lives of the highly educated” in the FTE sector.18

Black Americans are a minority of the population and of the low-wage sector, but the desire to preserve the inferior status of blacks has motivated policies against all members of the low-wage sector. Sometimes “black” is a metaphor for “others.” Since the FTE sector includes only the upper 20 percent of the population, blacks—even if they all were members of the low-wage sector—account for less than 20 percent of this sector. Hispanic immigration has brought in so many Latinos that they are now about as numerous as African Americans. Blacks and Latinos make up less than half of the low-wage sector, but not by much.19

President Reagan reversed fifty years of American domestic policy as he cut back federal grants to local and state governments that the federal government used to help poor people. Some benefits to individuals increased in the 1980s, but grants to governments declined or even—like general revenue sharing—disappeared. Public service jobs and job training were cut back sharply. The share of federal funding for large cities fell from 22 percent to 6 percent of their budgets. The decline of both private and public sources of employment in inner cities greatly reduced employment opportunities for white and black urban residents alike.20

The Reagan and Bush administrations reduced city funding, causing federal funding to drop sharply in the 1980s. Nixon’s New Federalism converted federal programs into block grants to states in order to give states more choice in how to spend the money. Reagan then revealed the underlying aim of the New Federalism by reducing and eliminating block grants.21

The effects of the New Federalism can be seen in the 2015 crisis of lead in the public water supply to Flint, Michigan. Flint was an auto manufacturing center, but that kind of employment ended soon after the Great Migration brought blacks to Michigan for good jobs. Blacks arrived to find reduced employment, and the city of Flint was unable to pay its bills. Governor Rick Snyder was elected in 2011 and supported a controversial law that allowed him to appoint emergency managers of cities in financial trouble. He put Flint into receivership and appointed an emergency manager in 2012. There were four different managers in the next three years, not an arrangement that was likely to yield comprehensive plans.

An emergency manager took Flint off the Detroit water system to save money in April 2014. He decided to take Flint’s water from a local river instead. The immediate result was brown water pouring out of the taps in people’s homes, and lots of complaints from residents about the new water supply. Detroit offered to reconnect Flint to its water system in January 2015, and to forego a substantial connection fee. A different emergency manager refused.

The complaints became sharper when high levels of lead were found in Flint’s water in February and March of 2015. This was known in the governor’s office, but no action was taken. In September of that same year, several doctors made a public statement that many Flint children had elevated levels of lead in their blood. Soon after the doctors’ news conference and a year and a half after the switch to river water, the state began to take action. Flint was reconnected to the Detroit water system in October.

But what about the residents of Flint who by then had high levels of lead in their blood and pipes into their homes that were damaged by the river water? The state government brought fresh bottled water to Flint for emergency help, but that was all it did. State funds were blocked by political objections, and federal emergency funds were blocked as well. It is unclear as this book goes to press whether the needed investment in Flint’s water pipes will be made. The residents of Flint are unable to move, locked in by home ownership and other constraints. But one of Flint’s emergency managers was rewarded by being put in charge of Detroit’s schools—of which more discussion will follow later—a position he resigned from after the Flint scandal broke.22

The governor and the managers, all from the FTE sector, did not consider the health of the black low-wage residents of Flint in making decisions about public services. The FTE sector representatives wanted to limit their taxes instead of preserving the infrastructure of Flint and guaranteeing good water quality. The Lewis model asserts that the FTE sector wants to keep incomes low in the low-wage sector, and that includes lowering the quality of public services in the low-wage sector.

All of these changes in employment, public financing, and private reorganization of labor produced frustration among unemployed and troubled people that came out in the use of cocaine. Federal penalties are heavier for crack cocaine (favored by low-wage African Americans) than for powder cocaine (favored by the FTE sector), and many black users of cocaine received heavy sentences as a result. This fed into Nixon’s War on Drugs, and state governments rushed to pass punitive laws such as the infamous three-strikes law that spread over the country in the 1990s, supported by ALEC and its draft laws. The prison population in the United States mushroomed from less than half a million to over two million inmates today, with drug convictions accounting for over half of the increase. Federal funding that formerly supported jobs in large cities now finances prisons in rural communities. There are now seven million people under the supervision of adult correctional systems, counting those in jail, on parole, or waiting for a court appearance. And although blacks are less than 15 percent of the population, they are 40 percent of the prison population.23

If incarceration rates stay the same, one in three black males will go to prison during his lifetime.24 This shocking estimate, based on data from life tables and prison records, implies that every black family knows someone who is in jail or has been in jail. Those released from jail are denied access to social programs in most states, preventing many male former prisoners from advancing in their lives to become good role models. Training prisoners for jobs is not a high priority, and most men released from prison have trouble finding work. They often see no way to earn money other than criminal activity, and recidivism is high. The proportion of black men in the prison population makes it likely that most black families have a male family member who is in jail or recently out of jail. Young men growing up in the shadow of the incarcerated men of their families find it hard to plan for the future, to gain skills that might help them in the future, or perhaps even to think of the future or education at all.

The War on Drugs has been directed primarily toward urban black males, and it has made it harder for them to advance from the low-wage sector. The process of incarceration takes black men out of society where they might accumulate skills. After they get out of jail, their past convictions preclude their participation in any of the government programs that help poor people get jobs, training, and food assistance. And the threat of prison in the black population—everyone knows someone in jail or under adult correctional system supervision—indicates to everyone that personal effort probably will not be rewarded. The prevalence of mass incarceration has become a form of social control.25

The assertion that mass incarceration is for social control more than crime control is supported by the continuing rise in incarceration rates over the 1990s while the crime rate fell. The causes of declining crime are not fully understood, but the evidence indicates that increasing incarceration had little if any effect. A recent survey concluded, “There is little evidence to believe that the higher [incarceration] rates have caused the reduction in crime in the last two decades.” Only budget shortfalls in the aftermath of the financial crisis of 2008 have produced a halt in the rise in prisoners, and long-time prisoners are not provided any help or services to reenter society when they are released.26

This repression falls most heavily on blacks, but it affects whites and Latinos in the low-wage sector as well. After all, the majority of prison inmates are white. But while poor whites are numerous, they are less visible than blacks in public discussions of programs to help the poor. Reagan’s famous invocation of “Welfare Queens” in his campaign to restrict government funding for the poor was a clear racial reference.27 The War on Drugs appears to be a law-and-order program, but its administration focuses on black men. And the resulting conditions of black men are used as examples to discourage other government funding. Even though people generally avoid racial language today, the persistence of race prejudice can be seen in the birther movement that attacked President Barack Obama’s legitimacy and the hateful responses to his debut on Twitter.28

Attempts to deal with one part of this complex of policies run afoul of racial discrimination and expose the strength of this underlying social construction. For example, recent efforts to reintegrate freed prison inmates into society by Ban the Box campaigns have tried to encourage employers to hire ex-felons by not forcing ex-prisoners to reveal their status in job applicants. A test of this policy in the New York area found that banning the box did not help black ex-felons get a job. Employers, prevented from gaining individual information, relied on general information that blacks were more likely to be ex-felons and refused to hire them. Ban the Box policies expose the underlying racism of our society and show how hard it is to help low-wage African Americans get ahead.29

The growing problems of white members of the low-wage sector are equally serious. White flight to the suburbs was by class as well as by race; it stranded poor whites in the inner cities, where they are subject to economic and social pressures similar to those of poor blacks. As noted earlier, there are many more whites than blacks and Latinos in the low-wage sector. The inability to earn an income sufficient to support a family increased among whites in poor urban neighborhoods after 1970. The urban white marriage rate dropped; the rate of urban white single-family households rose. The imprisonment rate among whites in poor urban neighborhoods rose along with the rising rate for blacks. And the decay of social capital in the form of trust among these whites was as severe as among blacks. The American dual economy would exist if there were no American blacks, but the political discussion would be different.30

The loss of social capital in urban parts of the low-wage sector has been chronicled separately for blacks and whites. As chance would have it, two studies were done in different neighborhoods of Philadelphia. They are similar as they describe the decline of social capital, but only the one about a black neighborhood focuses on the role of police in this decline.31 And national data reveal that over 40 percent of people living in families with female householders with no husband present now are impoverished, that is, below the American poverty limit.32

The similarity of social capital losses in poor urban neighborhoods, whether white, black, or Latino, supports Wilson’s assertion that the pathology of black neighborhoods was due to the economic circumstances they found in these cities. He asked if each characteristic of the lives of urban blacks in the 1990s—such as growing incarceration, declining marriage rate, and increasing single-parented families—were due to black culture or what he called institutional factors. He concluded that each was due to institutional factors. This conclusion can be generalized to both white and black members of the low-wage sector; they are characteristic of people trapped in unfortunate economic conditions with little ability to escape. Putnam also found losses of social capital in the low-wage sector through his interviews. He did not emphasize the role of race and incarceration, possibly because of the selection process for interviewees, and his results only show part of the story. They do however vividly illustrate and strengthen the evidence for the effects of our urban policies on the entire low-wage sector.33

There are differences between black and white communities in the low-wage sector in the form that social capital breaks down. For the black community, continued pressure from the police represents a constant threat to the acquisition of social capital. For the white community, the sense of being forgotten has resulted in self-destructive behavior that increased mortality from alcohol and drugs enough to cause the mortality of poorly educated white men to rise while the mortality of other demographic groups in America was falling. The recent political arousal of poorly-educated white men may be healthy for them, although the appeal to their superiority over similar black men is troubling for the future.34

The trap has become more restrictive as the welfare system has been criminalized. “The public desire to deter and punish welfare cheating has overwhelmed the will to provide economic security to members of society. While welfare use has always borne the stigma of poverty, it now also bears the stigma of criminality.”35 The welfare system increasingly is being used to catch people with outstanding warrants. It is easy to have an outstanding warrant if you are on parole and miss a meeting with your parole officer or violate some other restriction on your actions. Drug felons are not only barred from voting in many states, but also from the welfare system—marginalizing them more fully from society.

Welfare payments have eroded so that they no longer provide enough funds to live on. Most welfare recipients consequently have to rely on other sources of income to make ends meet. They have to engage in some income-generating activity that needs to be hidden from the welfare office to maintain benefits. This concealment is deemed a fraud, even though it is encouraged by the welfare system itself. Drug programs similarly are discouraged as drug use is not permitted on welfare, and again fraud is encouraged. The system creates incentives that maintain poor members of the low-wage sector in a marginal existence.36

Stories of people caught in the repressive legal system show its extent. On one hand, urban workers who are arrested find they cannot pay the bail required to stay out of jail until their case is heard. They are under great pressure to confess to a crime to avoid jail while waiting months and sometimes many months for trials—although this decision often makes them more vulnerable in the future. On the other hand, the system extends to small towns with only two or three policemen. In one such Vermont town, when the police found drugs, they only indicted whites 12 percent of the time, but they indicted blacks 87 percent of the time, seven times as often.37