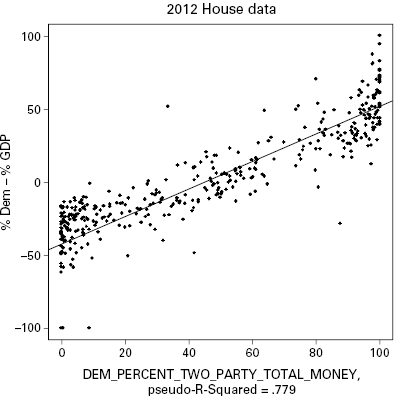

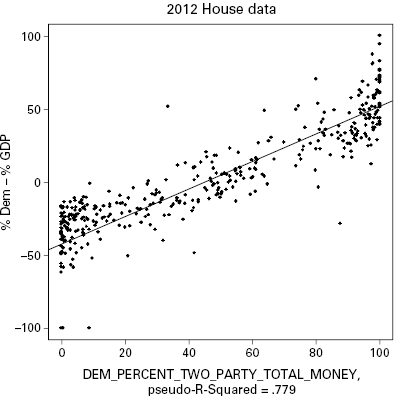

Figure 5 Money and congressional elections, 2012

Source: Ferguson, Jorgensen, and Chen 2013

I now have shown how America is split in various ways. The first split, discussed in part I, is economically. Income inequality has progressed far enough to think of the United States as a dual economy. The second, described in chapter 5, is racially. The relations between blacks and whites originated in early times in the New World, and they have taken many strange paths since then. Despite electing a black president twice in recent years, racism—that is to say, racecraft—has not disappeared. The third split is along gender lines, discussed also in chapter 5. Despite a lot of progress in recent years, women are still not fully equal to men.

How does all this affect American politics? This is a difficult question and will take some effort to answer. I start with the Median Voter Theorem and work toward other approaches that are more illuminating.

The Median Voter Theorem is used widely in both professional and popular discussions. The theorem starts from a simple example. Assume there is to be a vote on a single issue, and everyone voting has a view ranging from absolutely yes to absolutely no with room for various positions in between. If everyone voting is selected for reasons other than their views on the issue in question, then it is likely that voters are spread out along a bell curve or one-humped camel. Technically, the distribution is very likely to follow a normal distribution, with more people in the center than at the extremes.

The Median Voter Theorem predicts that political candidates facing preferences like this gravitate to the center, to the median voter, the central figure in the distribution of voters. This view of politics is quite common and has spread from academia to public discussions. For example, Edward Luce, a journalist forecasting events in 2016 for the Financial Times, predicted the Republican presidential candidate in 2016 “will be too far to the right of the median voter to make it to the White House.”1

This theorem appears to have strong predictions for politics in a dual economy. But it has serious problems. If the median person counted, American public policy would favor the low-wage sector. Since the low-wage sector contains over half the population, the median voter, if everyone voted, clearly is in the low-wage sector. But while the median voter would support, say, a higher minimum wage, it has not been raised in many years. Jamie Dimon, chairman of JPMorgan Chase, announced in mid-2016 that he was responding to the stagnation of wages by raising wages at JPMorgan Chase. This is laudable, but it is hardly the same as a raise in the national minimum wage.2

This paradox shows that the Median Voter Theorem is inconsistent with the dual economy. Lewis assumed that the lower sector of the dual economy had no influence over policy. Economic policy served the interest of the capitalist class; subsistence farmers had no political power. Lewis emphasized this point in the passages quoted in part I of this book to introduce his model by referring to the capitalists as imperialists, people who had little or no contact with the rest of society.

Many expositions of the Median Voter Theorem talk of people and voters as if they are the same people. But this approach is not appropriate in the United States. We have to go back to the origins of our Constitution to see why this is true and examine the history since then to understand how the Constitution was amended and reinterpreted.

The Constitutional Convention was convened in 1787 because the Articles of Confederation—the first written constitution of the United States, in effect from 1781—were not working. They had constructed a confederation of states that had no power to tax people; it could only bill states. It consequently lacked power to do much of anything else. The Convention was to propose a better alternative that would transfer some power to the federal government, but it had no power to enforce this change. Only if nine states of the Confederation ratified the Constitution would it go into effect. The Constitution therefore contained a series of compromises to persuade enough states to ratify it. Two differences among the states are relevant here: The states were (and are) of different sizes, and they were (and are) spread out from north to south.

The framers of the Constitution dealt with the different size of states by introducing a bicameral legislature. Representation in the House of Representatives was to be according to population, but each state was to have two senators, independent of the state’s size. In addition, senators were to be elected by state legislatures rather than popular votes. This arrangement, adapted from England, both restricted the reach of democracy in the new country and helped convince small states like Rhode Island to ratify the Constitution.3

This arrangement helped the United States to come into being, but it restricted democracy in the new country. The Senate would temper the decisions of the House of Representatives, and the people’s will was not directly linked to policy. The role of the Senate changed over time as the United States expanded westward and as agriculture was replaced by industrialization. People increasingly lived in cities, and cities were concentrated around ports. Atlantic ports were joined by ports on the Great Lakes and then on the Pacific Ocean. But while residents congregated in states with big ports and cities, senators came from states as they had been defined earlier. Democracy was limited by the contrast between the location of voters and the location of senators.

State legislatures had increasing difficulty appointing senators as the nineteenth century progressed. There were many gaps in the Senate in the late nineteenth century because the state legislatures could not agree who to appoint. The solution was to amend the Constitution to let the people elect senators. This was done in the Seventeenth Amendment, which took effect in 1913.

To the unequal counting of votes in the Senate, we must add the problems of redistricting the districts that elect U.S. representatives. This process has become politicized in the past several decades, and both parties have created safe districts for their members. As a result, ninety percent of representatives are in safe seats. The person wishing to influence public policy has the double burden of needing to live in a small state, for the Senate, with a competitive race for a representative. Very few American voters live in such locations.4

Despite this attention to the method of choosing senators, the Constitution makes no mention of eligibility to vote, instead turning the regulation of voting to the states. This was an odd way to write a constitution for a new democracy, but it was a result of the racial history of the American colonies told in chapter 5. The Constitution needed to be ratified by both Northern and Southern states to take effect.

The assumption that voters are the entire adult population may be more or less accurate for Europe, where voting rates hover around 80 percent of the appropriate population for legislative elections, but the picture is very different for the United States. The mean voter turnout in presidential elections was 56 percent from 1976 through 2008. The mean turnout for off-year elections for the House of Representatives was only 38 percent.

An analysis of voter turnout by socioeconomic status in 1980 reveals who actually votes in the United States. Over half of the middle class, as it was then known, turned out to vote, while only 16 percent of the working class and unemployed voted. As can be seen in figure 1, the middle and upper groups comprised much of the population in 1980, and the lower group did not vote. Classification by location reveals the source of this result. Voter turnout in the North and West in off-year legislative elections was above 50 percent until 1970, falling to 40 percent since then. Voter turnout in the South, however, was only about 10 percent from 1918 to 1950, rising to around 30 percent more recently.5

The proposed new constitution of 1787 contained compromises to attract colonies that stretched up and down the Atlantic seaboard of the newly independent union. The most important of these concerned slavery. Southern colonies wanted their slaves to count in the allocation of representatives in the House of Representatives. As slaves were then considered property, not people, they clearly were not voters. The demand for representation therefore conflicted with the idea of a democratic union. Northern colonies were reluctant to agree to this inconsistent demand, but they could not insist on excluding slaves entirely and have the Southern colonies agree to ratify. The compromise, as every schoolchild knows, was to count slaves as three-fifths of a person and ban restrictions of the slave trade for twenty years.

Given this compromise on representation, it was impossible for the Constitutional Convention to define conditions for voting. In fact, most planners of the early republic did not think that universal suffrage was a healthy part of the government. They thought property owners would have a stake in the new constitution and would preserve it well. How much property would qualify a voter? Could free blacks vote? Could women vote? These questions were too difficult and too distracting for the Convention, which passed voting arrangements to the states.

The result was that voting was never a right of all Americans; it was a privilege of a prosperous portion of the population. States experimented with allowing free blacks and women to vote, but these outliers did not last. Free black men were excluded from militias in New York, but they voted if they met property requirements. Single women who met property requirements could vote in early New Jersey, where voting laws were generic. But when women’s votes were thought to have affected the outcome of an election, the New Jersey legislature inserted gender specification in the voting law. During the Jacksonian period when property requirements for voting were lifted, race specification was inserted, and votes were reserved for white men. Keyssar calls it “partial” democracy, but it was an oligarchy in the South. Participation remained low as a result of these exclusions.6

The Civil War made surprising small alterations in this pattern. Voting in the South was more democratic during Reconstruction, but low turnout returned to the South due to Jim Crow laws and practices. Despite the Fourteenth and Fifteen Amendments, blacks were kept from registering to vote. The candidates in the general elections were chosen in primaries where far fewer people voted. These small gatherings of white people nominated sitting representatives and senators for reelection, and they were easily elected over and over. Their long tenure in Congress gave them enormous power because committee chairs were awarded by length of service. Due to the influence of these Southern lawmakers, the New Deal and the GI Bill delegated administration of benefits to the states. These benefits were confined to whites in the South, perpetuating this system.7

This pattern continues today. The Voting Rights Act of 1965 incorporated provisions to deal with the legacy of Jim Crow laws in the South. The Supreme Court ruled that its most effective provision was unconstitutional in Shelby County v. Holder in 2013. This provision required selected states and regions to preclear proposed voting arrangements with the federal government. In other words, the federal government would decide whether voting arrangements would violate the Voting Rights Act before they went into effect. The provision was ruled unconstitutional because the coverage formula was based on data over forty years old, making it no longer responsive to current needs and therefore an impermissible burden on the constitutional principles of federalism and equal sovereignty of the states.8

Despite the Supreme Court’s assertion that all states are alike, the states that had been listed in the original bill immediately rushed to impose voting restrictions that otherwise would not have passed preclearance. While it seems clear that these restrictions are racially motivated, they can no longer be phrased in that way. The difficulties of voting therefore affect low-wage whites and blacks.

Southern states turned to poll taxes to keep blacks from voting when the Voting Rights Act prevented the South from legally restricting blacks from voting. When poll taxes were made illegal in 1964, the states turned to literacy tests and voter ID cards instead. These measures avoided the opprobrium of singling out blacks, but they also prevented low-wage whites from voting. What began as a race issue turned into a class discrimination. And politicians in 2016 were concerned about the effect of these new requirements on voting; voter IDs appeared to be a large barrier to voting by poor people.9

The old Southern practice has been transferred to the North by mass incarceration. As noted already, the number of imprisoned grew rapidly after 1970, making the United States an outlier in the proportion of its population in prison. Prisoners often come from center cities and are disproportionally black. Prisons typically are built in rural areas where private employment has decreased as government revenues increasingly are distributed to rural rather than urban areas. The Supreme Court ruled that prisoners should be counted as part of the population, although prisoners cannot vote. White Northerners in some rural areas now find themselves in the same voting position as white Southerners under Jim Crow rules.10

Another problem with translating the Median Voter Theorem into practice is that voters typically face two or more issues in a political choice. For example, racecraft and economics might figure in a single vote. Donald Trump, Republican candidate for president in 2016, said that federal district court judge Gonzalo P. Curiel, in charge of the lawsuit filed against him by people who had lost money at Trump University should not oversee the case because the judge “was a Mexican.” When people noted that the judge hailed from Indiana, Trump still claimed he was unable to judge him because of his Mexican background. Paul Ryan, the Speaker of the House of Representatives, said that Trump’s attack on the judge was racist, but that he supported him nonetheless. In this situation, therefore, a citizen’s single vote ties together two issues: textbook racism and economics. The Median Voter Theorem does not tell the voter how to weigh this choice.11

Yet another way voting practices privilege the elites comes from the timing of votes. Tuesday voting restricts voting by low-wage workers who cannot get time off from their jobs. But there is no push to change this outdated practice. Tuesday voting began in the nineteenth century when most Americans were farmers and traveled by horse and buggy. They needed a day to get to the county seat, a day to vote, and a day to get home, without interfering with the three days of worship prevalent at that time. That left Tuesday and Wednesday, but Wednesday was market day. So, Tuesday it was. In 1875 Congress extended the Tuesday date for U.S. House of Representative elections and in 1914 for U.S. Senate elections.

Most Americans now live in cities, and it is hard to commute to jobs, take care of children, and get work done, let alone stand on lines to vote. This affects voters in the low-wage sector more than those in the FTE sector who typically have more control over their time. Census data indicate that the inconvenience of voting is the primary reason Americans are not participating in our elections. Some states have closed polling places in addition, leading to long lines and waits for potential voters. Early and absentee voting makes life easier for some voters, but states trying to limit poor voters cut funds for these activities, requiring more time and effort from voters. Columbus Day, Presidents Day, and Martin Luther King Jr. Day are all scheduled on a Monday for the convenience of shoppers and travelers, but we have not adjusted to modern conditions to make voting more convenient for the sake of low-wage workers. There is little discussion of the timing of elections today, but one way to increase voting participation would be to change Election Day from Tuesday.12

Morgan Kausser and Alexander Keyssar remind us that the history of voting rights is not smooth and unidirectional. African Americans acquired voting rights in Reconstruction, but swiftly lost them again due to congressional and judicial decisions. They regained these rights in the Civil Rights era, but they are losing them again in “radical reinterpretations of the Voting Rights Act ... and the revolutionary reading of the equal protection clause introduced by the ‘conservative’ Supreme Court majority.” This revolutionary reading became law in Shaw v. Reno, 509 US 630 (1993), when the Supreme Court subjected redistricting by race to strict scrutiny.13

Supporters of the Median Voter Theorem do not seem to notice these historical roots of voter participation variation. Perhaps they were reassured when women got the vote in the Nineteenth Amendment and nothing changed. The expansion of the vote came after the First World War when voting restrictions were lifted in several countries. The national organization of suffragettes distanced itself from black suffragettes, but “the South remained opposed, with the full-throated cry of states’ rights giving tortured voice to the region’s deep anxieties about race.”14

Nevertheless, giving women the vote seemed not to affect national elections. Class rather than race had become central—at least outside the South—and women came from the same classes as men. They voted with men, and political scientists saw vindication of the Median Voter Theorem.

In addition to the problem of a partial democracy that restricts voting, the cost of getting information in order to vote does not play much part in the Median Voter Theorem. The theorem assumes that voters are spread out on a single line, caring only for one issue in any election, and that they all know their own preferences. Those assumptions go along with the way competition is taught, where consumers choose what kind of bread or tea to buy at the supermarket on the basis of freely available information. There is little mystery to consumer choices like these, and political theory here followed the economic presumption.

Within economics, the assumption of abundant free information has eroded in recent years. In our complex civilization, people need to take time and sometimes spend money to get information to choose which product to buy. No one buys a smartphone, car, or house without getting some knowledge about what they intend to pay for. Workers seeking jobs often have to search to find one that fits their skills and needs. And it’s a necessity for most adults to gather information about medical care, from finding a good doctor to choosing among various medications. Many economists have analyzed costs of information in diverse markets.

Information has costs, even if they are only the cost of time spent finding and absorbing the information. People with higher incomes can make more exhaustive searches for information about the goods and services they need. And the sellers of these goods and services invest vast amounts of resources in making information about their products available and accessible to potential customers. Advertising is the most obvious expenditure; consumers are surrounded with ads all around and in all forms, from the ads that line the subways to the ads on TV and the Internet. There are questions about the quality of information received through ads. The benefits of an advertised product often are exaggerated, and drawbacks or even dangers may be omitted. There are regulations for some kinds of ads, but there is a lot of room for unscrupulous businesses to take advantage of people.

Brand names provide one way to lower the cost of information to consumers. Many people rely on a familiar brand name as a signal to them that their purchase will provide the quality they seek. This lowers the cost of information to customers greatly. It is, however, costly for a company to establish and maintain a good brand name. Companies need to provide quality products for long enough for potential customers to know about and use and begin to trust their brands. And companies need to maintain the quality of their brand-name goods and services; even a temporary lapse can cause damage to the brand and subsequent sales.

Elections pose complex questions that rival the biggest purchases we make. For example, some candidates in recent political campaigns have made the claim that the Social Security program is about to run out of money. What does that mean? Is Social Security like your mortgage, so that running out of money means that you cease to get your pension—you are evicted from the system? Or that keeping people covered will mean benefits must fall across the board? It is hard to know from the many speeches that anticipate some kind of disaster what actually is going on.

There are problems with the current financing of Social Security that should be addressed in a calm fashion, but the strident tone of political rhetoric tends to obscure rather than explain them. A brief review of how Social Security works demonstrates how much information is needed to make an intelligent choice about the future of this program.

Social Security is not a pension plan where you pay in while young and collect when you reach a certain age. It is funded each year by taxes that workers pay to finance the expenditures due to current Social Security recipients. Since taxes in any year do not exactly equal the amounts needed for Social Security payments at that time, there is a buffer called the Social Security Trust Fund between the taxes and payments. This trust fund was built up in the last few decades to prepare for the enormous number of Baby Boomers born after the Second World War who would be collecting benefits.

Baby Boomers are now aging and have increased the number of Social Security recipients. The trust fund is now decreasing as the population ages. The Social Security administration is required to plan for seventy-five years in the future, which involves predictions about the changes in the relevant population. Current population projections indicate that the trust fund will be depleted within seventy-five years under current rules. The trust fund will be exhausted soon, and legislation is needed to deal with the problems this will raise.

Social Security is not about to collapse. It is the Social Security Trust Fund, not the whole system, which is running out of money. If the trust fund is exhausted and nothing is done, then benefits will be reduced. This will cause hardships for many Social Security recipients, but it does not mean the end of Social Security. The trust fund was close to being exhausted in 1982, and Congress took action to revise the system.

Social Security taxes are collected on wages only up to $118,500; the limit could be raised or even eliminated to balance the system. This cap on earnings subject to Social Security tax was set before inequality rose, and it now stands close to the boundary between the FTE and low-wage sectors. Raising the limit of wages subject to tax therefore would extend the funding of Social Security into the FTE sector. But the FTE sector is not interested in helping the low-wage sector, and nothing has been done.15

There are problems with Social Security, but people need information to understand the choices on how to address them. There is no imminent disaster. Instead there are problems that come up as conditions change and have been dealt with periodically. The latest major revision was instituted thirty years ago when inequality was not as severe as it is now, and there is a need to revise the taxes or benefits for the longer run again. These measures normally were taken by bipartisan actions and commissions set up for the long-run plans. If nothing is done at the moment, Social Security benefits will fall, and there will be administrative problems with intergovernmental payments.

How are voters to understand all this? Unfunded benefits like Social Security have almost disappeared for most workers. The history of Social Security also is unfamiliar. The choices have only appeared as occasional talking points; they have not been calmly compared to alternatives. The cost of information is high, as ordinary people need to find out where to get the relevant information and then how to access and understand it. Without that information, voter attitudes will be based more on emotion than reason.

Social Security is a relatively simple issue. Questions of government deficits or debt are far more complex. There are no simple rules or simple corrections that are needed. There are instead many separate parts that go into both the causes and the effects of these aggregate measures. Voters have very little access to this information and very little background in the reasoning used to produce plans. It is extremely hard if not impossible at times for them to have enough information to make reasonable voting choices.

Many voters in the low-wage sector want to know why their wages have not grown in the past thirty years, as shown in figure 2. Why are their wages disconnected from their productivity? Why has the American dream been denied to them? As explained in chapter 3, this is a complex problem with many parts. It is inconceivable that many members of the low-wage sector could find the information needed to put this picture together. Voters therefore have to rely on others to give them help. But who will provide the information?

As with complex goods for sale in our economy, people with money are advertising solutions to these problems. Just as large businesses dominate the information for consumer choices, large political organizations dominate the information for political choices. And brand names—party names in this case—summarize the information for voters. The problem is that there are only a few brand names in the political sphere, and there is no separate information available on the many issues voters need to take into account when voting. Voters need to know not only what they think about a variety of issues, but also how important these disparate choices are in casting a single vote.

The absence of political knowledge makes the Median Voter Theorem problematical. For example, Larry Bartels, a prominent political scientist working with the Median Voter Theorem, considered voters’ opinions about the Bush tax cuts in 2001 and 2003. Finding that many ordinary people favored them, he asked incredulously: “How did ordinary people, ignorant and uncertain as they were in this domain, formulate any views at all about such a complex matter of public policy?”16

Similar questions arise in considering the invasion of Iraq in 2003. This invasion may have been a logical consequence of Nixon’s Project Independence. It also was the consequence of George H. W. Bush’s advisers: “Washington developed an Ahab-like mania regarding Saddam [Hussein]” in the 1990s. The invasion of Iraq was decided on by the Bush administration and then sold to the country, mostly by Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice and Vice President Dick Cheney. Not only was the military exempt from the desire for small government favored by the new conservatives, the war also was to be sold to the American public, not decided by them.17

There is no consideration of the barriers preventing some people from voting, and no consideration of the costs of information required to make choices in the Median Voter Theorem. These important aspects of the electoral process need to be brought from the periphery to the center of analysis.

An alternate approach starts from the cost of information discussed here. Just as business firms invest in providing information to consumers, political groups invest in providing information to voters. They make investments to convince people to vote just as business people make investments to convince others to buy. And large political organizations have the resources to make big investments in political education, just as large businesses have the resources to produce many ads and maintain many brands. This theory is known as the Investment Theory of Politics.18

This theory argues that the effects of voting are determined by entities—businesses, rich individuals, PACs—that are able to make large investments in political contests by various means. One way is to control who can vote, allowing only those people who will vote the way the investing entity wants. Another way is to advertise these entities’ views heavily—on TV and on electronic billboards—and with powerful impact because voters have trouble getting other information about the effects of their votes. Voters typically need costly information for any single issue. Lacking the time or energy to get this information, they rely on advertising and party identification. They also have to vote on a small number of candidates. Each candidate represents positions on a bundle of decisions, and voters have to choose between these packages.

In the Investment Theory of Politics, in contrast to the Median Voter Theorem, voters are spread around a multi-dimensional space with scarce information needed to determine their position in each dimension. Faced with a small number of candidates, voters rely on the signals they receive from rich and powerful entities that invest in making their bundle of preferences attractive. Who can doubt the Investment Theory of Politics when politicians spend so much of their time and effort raising money? The result is that voters have less influence on political outcomes than the investing entities.

Elections become contests between several oligarchic parties whose major public policy proposals reflect the interests of large investors. The Investment Theory of Politics focuses attention on investors’ interests, rather than those of candidates or voters. The expectation is that investors will not be responsive to public desires, particularly if they conflict with their interests, and they will be responsive to their own concerns. They will try to adjust the public to their views, rather than altering their views to accommodate voters. In other words, the Bush administration’s policy of selling the Iraq War to the American people was the norm, not the exception.19

Bartels analyzed roll-call votes on the minimum wage, civil rights, budget waiver, and cloture. He found that “senators attached no weight at all to the views of constituents in the bottom third of the income distribution. ... The views of middle-income constituents seem to have been only slightly more influential.” He found in an analysis of social issues that “even on abortion—a social issue with little or no specifically economic content—economic inequality produced substantial inequality in political representation.” Bartels concluded from the analysis of many examples “that the specific policy views of citizens, whether rich or poor, have less impact on the policy-making process than the ideological convictions of elected officials.” This is what the Investment Theory of Politics predicts. Bartels’s amazement confirms both the power of the Median Voter Theorem among academics and its great limitations in the analysis of American policy formation.20

The public appears more aware than political scientists of what is going on. Two-thirds of people interviewed in a recent Gallup Poll thought that major donors had a lot of influence over congressional votes. When Gallup arranged survey results by the extent to which respondents knew about the structure of the American government, the more knowledgeable people were more likely to say that major donors had a lot of influence—while people in the district electing Congress members had almost no influence.21

The source of these findings can be seen in the 2012 congressional elections. The proportion of votes cast for Democratic representatives was closely related to the amount of money spent on their behalf as shown in figure 5. In fact, the observations are so tightly clustered around a straight line that the figure suggests that the expenditure of political funds is the most important determinant of party votes. The figure also reveals that the relation is linear: more money yields more votes. Personalities, issues, and campaign events are the focus of newspaper stories, but money is the prime determinant of the electoral outcome. Voter views captured by interviews may appear decisive, but they are in fact the mechanism by which the money spent affects votes. A more dramatic confirmation of the Investment Theory of Politics is hard to imagine.22

Figure 5 Money and congressional elections, 2012

Source: Ferguson, Jorgensen, and Chen 2013

A new working paper by the same authors extends figure 5 to congressional elections since 1980. With the exception of one or two elections at the beginning, all the graphs—for both senators and representatives—look exactly like figure 5. The Investment Theory of Politics explains congressional votes well for the past thirty-five years. While there is more money in politics now and the role of dark money has mushroomed in recent years, money has been driving American congressional elections for many years.23

Anecdotal information suggests that figure 5 applies to local elections also, but the information is not available to make a formal test. The problem is the growth of dark money, that is, money from unidentified sources. The Brennan Center for Justice studied local elections in several states after 2010 and found that almost forty times as much dark money was in use in 2014 as in 2006. Three-quarters of outside spending in 2006 was fully identifiable, but only about a quarter was transparent in 2014. This growth of political spending without oversight facilitates corruption, and it is best understood through the Investment Theory of Politics.24

A study of almost two thousand policy decisions made in the past twenty years extends this result on voting to policy decisions. The authors distinguished two kinds of interests: majoritarian interests reflecting the views of median voters and elite preferences typified by the 90th percentile of income distribution, that is, by the top half of the FTE sector. They found that the interests of the elites were very different and sometimes opposed to those of the median voters. The policy outcomes did not reflect the median voters’ views, seen as the majoritarian views. When the interests of the majority opposed those of the elites, they almost always lost out in political contests. The strong status quo bias built into American politics also made it hard for the majority to change policies they disagreed with. In short, the Investment Theory of Politics is a far better predictor of political contests than the Median Voter Theorem.25

The Investment Theory of Politics reveals how politics works in a dual economy. The FTE sector dominates decision making, and the low-wage sector is shut out of this process. This exclusion is preserved in a supposedly democratic society by maintaining that voting is a privilege, not a right, restricting access to voting by the low-wage sector, and by the promulgation of information by the businesses and rich individuals who want to steer policy toward the FTE sector. In short, we are living by “the Golden Rule—whoever has the gold rules.”26