Figure 6 Change in occupational employment shares in low-, middle- and high-wage occupations in 16 EU countries, 1993–2010

Source: Goos, Manning, and Salomons 2014

I argue in this book that the United States economy has developed into a dual economy in the spirit of W. Arthur Lewis. The prosperous part of the economy, known as the FTE sector, is the sector that readers of this book most likely live in and often envision as the whole American economy. The depressed economy, known as the low-wage sector, is the largest part of the American economy nonetheless. The decline of the middle class has left us with these two parts of an economy, governed by policies made by the FTE sector for the benefit of the FTE sector.

This book is about the United States, but is the United States unique? I expand the focus here to see if parts of the American dual economy model apply to other countries as well. The growth of inequality extends beyond the United States, but politics are different in other countries, and only in some countries have the politics turned the economic forces into a dual economy. Consider three propositions. First, the world income distribution has become more equal in the period discussed here, from the 1970s to the present. Second, the failure of incomes in the American low-wage sector to grow is apparent even on the world stage. Third, political decisions in the context of national histories are needed to resolve the contrast between the first two propositions.

To understand this conflict, start by distinguishing inequality within countries from inequality between countries. This book considers inequality within America, and only now places the United States in a world context. While inequality within countries has increased in many countries, inequality between countries has decreased around the world. Overall world inequality therefore has not changed much in recent decades, although the location of inequality is changing.

It also is useful to distinguish movements at the top of the distribution from those at the bottom, as argued earlier for the United States. Inequality between countries has decreased mostly due to economic growth benefitting poor people in China and India, while inequality within countries has resulted mostly due to increasing incomes among the richest people.1

For the richest, the growth of finance, technology, and electronics has increased their incomes both because they have done well within their own countries and because they have engaged in international commerce. Globalization increased the reach of financial and industrial activities, providing greater scope for any individual action. As American firms became active around the world, they enlisted local counterparts and established new businesses. Political decisions within countries moderated the growth of inequality in some countries, and the degree of inequality across countries is a result of both economic and political decisions.2

For the poorest, the forces of globalization just noted for the American low-wage sector have subjected workers to ever more international competition. Add to that the technical change that enabled machines to do the work of semi-skilled workers, and you have similar divisions of workers around industrial countries.

Figure 6 extends the analysis of varied job growth in figure 4 to European countries, where the hollowing-out effect is stronger than in the United States. If the United States were added to figure 6, it would be near the right-hand end, with a smaller effect of technology on mid-level jobs. The effect of the new technology was stronger in Europe than it was in the United States, and the share of European workers in highly paid jobs rose to slightly more than one-third in 2010. Political decisions moderated the effects of the shifting demand for labor on unskilled workers in several European countries; the results on the distribution of income were affected by both economic and political decisions.3

Figure 6 Change in occupational employment shares in low-, middle- and high-wage occupations in 16 EU countries, 1993–2010

Source: Goos, Manning, and Salomons 2014

The comparison of figures 4 and 6 reveals the power of political choices in America. The change in the distribution of jobs was relatively small in the United States, but the increase in inequality was relatively large. The preceding chapters of this book showed how the peculiar history of the United States led to the American dual economy. None of the European countries has America’s long history of African slavery and subsequent efforts to subordinate African Americans in other ways. Without the American attempts to divide populations into different groups—us and them—economies of rich and poor may not have separated into dual economies. The great flow of Syrian refugees to Europe in 2015–2016 may produce something like the American division if measures are not taken to avoid it. Only studies of individual countries can illuminate how economic and political factors have worked out within each country.

This account shows how the United States can stand at the top of the countries in per capita income—behind only Switzerland and Norway—but rank sixteenth in social progress indicators. This is still high among the 133 countries listed, but distinctly lower than other rich countries in the index of basic human needs, foundations of well-being, and opportunity. Had we the data to see only the FTE sector, its social progress rank undoubtedly would be close to its per capita income rank. But the low-wage sector has a far lower score in the index and drags the national index down. For example, the United States ranks very far down the list of countries by the proportion of children in poverty, with a rate of child poverty more than twice as high as the Scandinavian countries and close to the rates in Spain and Mexico.4

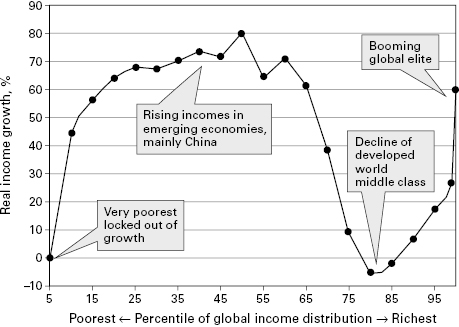

Another graph helps us see the United States in a world context. Figure 7 shows the growth of individual incomes in the twenty years before the global 2008 financial crisis by the relative income of different groups of people. As you can see, this is not a bell curve; it looks more like an elephant. This graph shows results of household surveys conducted in many countries and combined in the Luxembourg Income Study, World Bank studies, and regional sources. There are difficulties in comparing surveys from around the world and in different currencies, but the main outlines shown in the figure appear clear.5

Figure 7 Global income growth from 1988 to 2008

Source: Milanović 2016 (explanatory boxes added)

The elephant’s back shows how the growth of incomes in China, India, and smaller countries is reducing income inequality between individuals in different countries. The back feet of the elephant reveal that the poorest people, many of them in Africa, have been left out of this growth. And the elephant’s trunk shows what has been happening in richer countries. The high point at the top right of figure 7 represents the growth of the very rich in the United States and elsewhere, and the low point shows the stagnation of worker’s wages in the United States and other rich countries.

One way to calibrate this contrast is by comparing the experience during the last two decades of low-wage workers in the United States with the experience of highly paid workers in China. The American group had stagnant earnings, while the income of the Chinese group grew rapidly. Far apart in 1988, the two groups were very close by 2008. Branko Milanović called the losers in this comparison the “lower middle class of the developed world” and summarized the argument made here as follows, “Technological change and globalization are thus wrapped around each other.”6

Anthony Atkinson, in a book about inequality in England and Europe, agreed, “The twin forces of technological change and globalization ... are radically reshaping the labor markets of rich and developing countries and leading to a widening gap in the distribution of wages.” Atkinson went on to agree with the views expressed in chapter 3: “Technological progress is not a force of nature but reflects social and economic decisions. Choices by firms, by individuals, and by governments can influence the direction of technology and hence the distribution of income.”7