Marjorie Diehl had met the woman in late July 1984, on a cheese line. They met a week before Diehl fatally shot Bob Thomas. Diehl, thirty-five years old, and the woman, Donna Mikolajczyk, who was fifty, made a quick connection. Diehl came to like Mikolajczyk, who had just been released from the State Correctional Institution at Muncy, in central Pennsylvania. The prison stay interested Diehl. She listened to Mikolajczyk even more when Mikolajczyk started talking about how her boyfriend beat her and sexually abused her. Diehl thought she knew precisely what Mikolajczyk was talking about.1

“Yes, I am the same way,” Diehl recalled telling Mikolajczyk.” I’m scared of my boyfriend and he beats me, too, and he sexually abuses me, too.”2

The two also spoke about how Diehl wanted to sell some of the surplus butter and cheese they had been getting at a food bank in inner-city Erie. Lots of people made such illegal transactions, which created a black market for government foodstuffs.3 For one reason or another—for assistance in selling surplus food or for advice on how to cope in an abusive relationship—Mikolajczyk told Diehl that day on the cheese line to contact her if she ever needed help. Mikolajczyk wrote her address on a scrap of paper.

Diehl soon visited Mikolajczyk’s house. She stopped by at about one o’clock in the afternoon on July 30, 1984. Diehl said she needed help.

“Donna, I need a friend,” Diehl said. “I have a psychic feeling about you. We’re into astrology. Could you keep your mouth shut for a lot of money?” She said she had shot her boyfriend to death, and she wanted to get rid of his body. She offered Mikolajczyk $25,000 if she would lend a hand. Mikolajczyk thought Diehl was joking until Diehl pulled out more than $18,000 in cash.4

Diehl had $18,401.80 in a zippered blue bank bag in her gray purse and another $925 in food stamps. She was also toting two yellow plastic grocery bags bursting with stuff, as if she had become a hoarder on the move or a hoarder ready to go on the lam. One bag contained, among other things, keys, a rod for cleaning a gun, a glass ashtray, a comb, barrettes, scissors, a letter holder, a case for holding eye contacts, contact solution, and a pair of hands painted gold.5 The other bag was heavier. It contained, in addition to the cash, items such as tubes of lipstick; other containers of makeup; small change purses; a Canadian dime; an Erie police accident report; magazines; a newspaper; five pens; Diehl’s Social Security card; Thomas’s Social Security card; her identification card for getting surplus food; papers related to her landlord and erstwhile boyfriend, Edwin Carey; receipts, including the receipt for the .38-caliber Smith & Wesson revolver she used to kill Thomas and that she bought at a downtown Erie sports store five days earlier, on July 25; a business card for a local lawyer; two sets of keys; a gold watch; and a black telephone that Diehl had unplugged from her rented house on Sunset Boulevard, where Thomas had been staying with her.6

The phone had been near Thomas’s dead body, which, hit with six bullets, was still bleeding on the couch in the living room in the house. Diehl told Mikolajczyk she was worried that Thomas might still be alive, would wake up, and call for help. So Diehl brought the phone with her.7 She also brought the gun. Inside one of the bags was a box that contained the revolver Diehl had used on Thomas about eight hours earlier. Six spent bullet casings were still in the gun. Diehl had not called the police.

Shortly after killing him, she had changed out of her nightgown into a purple sweater and blue jeans, packed the grocery bags, and got in her car, a blue 1974 Gremlin with a white stripe.8 Diehl later said she had thought about killing herself, but she collected her thoughts, grabbed the gun and the bullets and the other belongings, and drove to her parents’ house. She was thinking about running away.9

Diehl had seen her parents only sporadically over the last fourteen years, after she had moved out of their house at age twenty-one. Her parents, she thought, would be willing to help. She pulled the Gremlin into the driveway and knocked on the back door of the house. Her parents, both in their early seventies, stood at the door and listened, trying to figure out what their only child was trying to say. Marjorie Diehl later said she only told her parents that “something happened,” but did not tell them that she had killed Bob Thomas. They both had high blood pressure, and she was worried that full disclosure would cause both of them to suffer strokes.10 Diehl never got the refuge she wanted.

Diehl left the house and drove to a bank. If she was going to run away, she needed money, and she had access to it. Even before going to the bank, she had about $12,300 in cash, which her lawyers in the Thomas case later said she had received in a settlement over a car accident,11 though they were evasive about all the facts.12

Diehl got the rest of the money when, after killing Thomas, she went to the bank and cashed a check for $5,656.37 in back Social Security disability benefits.13 She placed all her cash, now more than $18,000, in the zippered banker’s bag and drove to a downtown radiator shop, where, still thinking she might want to run away, she paid $58.19 for repairs to a hole in her Gremlin’s radiator.14 While she waited for the car, Diehl walked across the street to a shopping mall, where she used a pay phone to call her parents. They were not home. She went into a bathroom and vomited. Opening her purse to find a comb, she came across the piece of paper on which Donna Mikolajczyk had written her name and address when the two were on the cheese line.15 By coincidence, Mikolajczyk lived about a block from the shopping mall. Diehl got into her newly repaired Gremlin and drove over.

Diehl told Mikolajczyk that she had killed Thomas and that she needed help getting rid of the body. Diehl said she was justified in the slaying. She explained that he had come at her that morning. “I had to kill him,” Diehl said she told Mikolajczyk.16 The remarks stunned Mikolajczyk.

“At first, I didn’t believe her, but she said the man had treated her terribly,” Mikolajczyk said the night of Diehl’s arrest. “He had beaten her and she had finally shot him. She said she didn’t mean to do it, but he slapped her and just kept coming at her, pushing her. You should hear the things he did to her. And he was always looking at younger women, she said, even kids. Personally, I think she deserves a badge.”17

Mikolajczyk said Diehl convinced her she was serious about getting rid of Thomas’s body when she pulled out the cash.

“But then I believed her. When she showed me the money,” Mikolajczyk said. “She had $18,000 in cash. I don’t know where she got it. But she said her family was well-to-do. She would give me $25,000 if I would help her.”18

The two talked for hours about what to do with Thomas’s body. Unclear, according to testimony and interviews, was who offered the ideas first. But Diehl and Mikolajczyk agreed the conversation happened.

“I told her she couldn’t bury it because that would be too much work and there still would be bones if someone ever found it,” Mikolajczyk said. “I said you could not dump it off the pier because of the Coast Guard. And people would see you if you burned it.”19

Mikolajczyk and Diehl walked to the shopping mall so Mikolajczyk, now frightened, could use the pay phone. She called her sister, Susan Lasky, who drove over. Mikolajczyk and Diehl got in Lasky’s car, and Diehl repeated her offer: that she would pay $25,000 for help in disposing of Bob Thomas’s body. Diehl insisted that she get rid of the body to prevent police from linking her to the bullets investigators would find inside the corpse and around the house.

“The gun is registered and they’ll find the bullets and trace it to me,” Diehl said.20

“Did you do it?” Lasky said.

“Yes, I did,” Diehl said.21

Lasky was repulsed.

“Get the hell out of this car,” she told Diehl. “I wouldn’t do anything like that for $25,000 or $150,000.”22

Diehl would not get out of the car. She seemed confused to Mikolajczyk, who thought Diehl needed a friend. To her, Diehl was acting hurt, “like a beaten puppy.”23

Mikolajczyk and Lasky persuaded Diehl to get out of the car by telling her they would meet her later at a bar. The sisters telephoned their mother, who called the police. Mikolajczyk and Lasky gave descriptions of Diehl and her car. By six o’clock that evening, the police had found Diehl, not far from Mikolajczyk’s house—a woman in the blue Gremlin with the white stripe and carrying two yellow plastic grocery bags filled with a gun, bullets, a phone, and other stuff; plus more than $18,000 in cash.

The detectives read Diehl her rights at the Erie police station. She told them she shot Thomas at about seven thirty that morning.

“He threatened me,” she said. “I have a mental disability. He’s paranoid-schizophrenic. He came on me with the Vietnam shit, post-traumatic syndrome. I got manic and scared, and that was all. I told him last week I was getting a gun. . . . I told him I had the gun when he came after me. I freaked out.

“We were in the living room. I was sitting there. He told me, ‘My hands are lethal weapons. I learned it in Vietnam,’ and he came at me. I told him I got the gun; leave me alone. And he said, ‘Ha, ha, ha. I’ll take the gun away from you.’ So I figured, Well, I’m not going to give you the chance. I figured he’d kill me.

“I just fired the gun, and he fell back on to the couch. That’s where he was when I left.”24

Diehl continued to talk while she was in the holding cell at the police station. She said Mikolajczyk, not her, wanted to dispose of Thomas’s body. She said she was afraid of Thomas, and that it was just a matter of time before he killed her, so she shot him.

“It would have been better if I had just wounded him,” she said.25

Diehl said she had never seen a dead man before, and that Thomas’s body was the grossest thing she had ever witnessed. She said she had warned him that she had a gun, and she said she was not a good shot. Diehl said “she hoped against hope” that Thomas was not dead.26 By then, the police, using a key obtained from Diehl and after getting a search warrant, had already visited her house on Sunset Boulevard. Edwin Carey, Diehl’s landlord, let the police in. The officers and detectives found Thomas’s bloody body on the living room couch, amid the junk and rotting food.

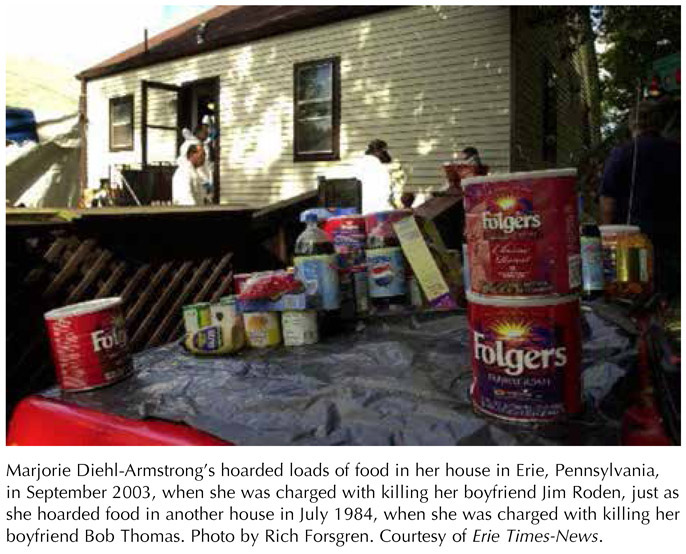

“It might be noted,” Erie County Coroner Merle Wood wrote in his report on the homicide, “that the kitchen area was in complete disarray with food mostly in boxes, lying on the sink area and kitchen table. The cupboards were completely full of food. In addition, two refrigerators & a cooler were full of food, mostly which was butter.”27

Wood ruled that Thomas had died at 7:13 a.m. on July 30, 1984, and that the cause of death was a laceration of the aorta due to a gunshot wound to the chest. Thomas, wearing pants and a short-sleeve shirt with the buttons open, had been shot six times. The bullets were fired at a close enough range that, according to Wood’s report, “Powder burns were visible around four holes in the shirt, one which was over the left pocket, two on the left shoulder & one in the upper left arm.”28 Thomas also had a gunshot wound behind the left ear and another to his left wrist. Thomas’s body, the coroner wrote, was “lying on his right side on the couch with his feet on the floor & his head . . . lying on the arm rest. The lower portion of his body was covered by a plaid throw.”29 Investigators recovered three slugs from Thomas’s body and another three from the house, including two from behind the sofa. The police also recovered a box of .38-caliber shells, less six rounds.

Diehl was still prescribed the antidepressant Tofranil when she was arrested. Her prescriptions would change over the next several years, as medical professionals tried to set a course so she could reach a degree of mental stability to stand trial. Diehl and her defense team initially contemplated but never pursued an argument that she was legally insane—that, though she indisputably killed Thomas, she was nonetheless not guilty because she had no idea of right or wrong when she pulled the trigger.30 Her lawyers instead argued that she was mentally incompetent to stand trial—that, because of her bipolar disorder, narcissism, paranoia, and other mental problems, she was unable to cooperate with her lawyers and assist in her defense. Diehl, her lawyers quickly found, was obstreperous and believed she was smarter than they and everyone else. “You’re so full of shit your eyes should be brown,” she once told one of her lawyers.31

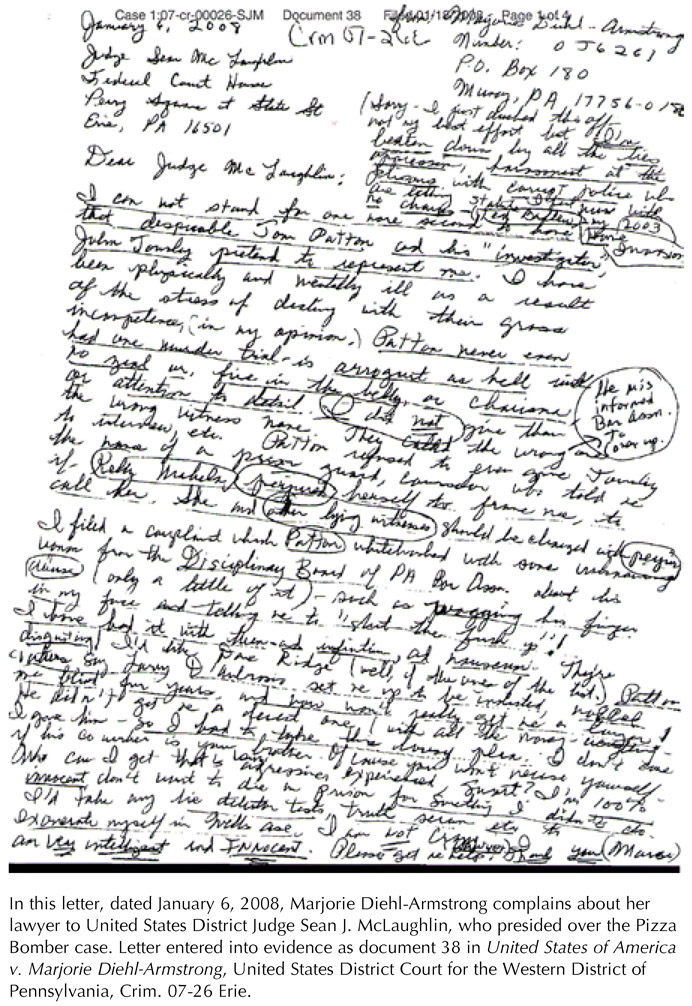

While awaiting trial in the Thomas case, Diehl also started a practice that she would continue throughout her other cases, including her prosecution in the Pizza Bomber case. She constantly wrote letters to the judge—in the Thomas case, Erie County Judge Roger M. Fischer. She used the handwritten missives, in which her scrawl covered nearly every spot on the page, to rail against her attorneys, proclaim her innocence, and plead for an opportunity to reenter society. “I am not crazy or dangerous,” she wrote in one letter to Fischer. “I have a serious nervous condition but need a chance. . . . I want to lead a decent life. I have no criminal record and was never an alcoholic or a drug addict. Old friends, neighbors, and clergy support me.”32

At first, Diehl had the benefit of preparing her defense in the Thomas case while she was out of prison. Over the objections of the Erie County District Attorney’s Office, Fischer on August 27, 1984, ordered Diehl released from the Erie County Prison on $10,000 bail, or 10 percent of the full bond amount of $100,000. Harold Diehl posted the bail, and he had pledged at a bond hearing three days earlier that he and his wife would monitor their only child while she was free and awaiting trial for murder. Harold Diehl was in tears when he told Fischer that he would take Diehl in when she was released. “She would be living in the same room that she always had when she lived with us,” Harold Diehl testified.33 Marjorie Diehl also testified at the hearing; the judge and the prosecution and defense got their first insights into Diehl’s treatment history and her present mental state. This was the hearing when Diehl reacted with anger when the prosecutor—trying to show that she would be a danger to the community if she were released on bail—confronted her with the social worker’s diagnostic impression, in 1972, that she had “a deep-seated hatred of men.”

Diehl enjoyed her freedom for only a brief period. On December 4, 1984, Judge Fischer signed a bench warrant at the request of the prosecution to revoke Diehl’s bail and keep her in prison while she awaited trial. The impetus was an accusation that Diehl four days earlier had solicited a state prison escapee to kill two people who refused to testify as character witnesses for Diehl in her soon-to-be scheduled trial for Thomas’s death.34 Detectives with the District Attorney’s Office taped phone conversations between Diehl and the supposed hit man, though Diehl said the recordings showed that the man, and not she, brought up the idea of hurting the potential witnesses. Diehl said she was innocent of the plot and accused the purported hit man of coming up with the scheme and framing her. The man helped himself little by contradicting himself at Diehl’s bond revocation hearing, at which he also testified he had withheld information from the Erie police and the District Attorney’s Office in their investigation of the plot.35 Diehl said the man could not be trusted.

She shouted when the man testified at the hearing. “I can’t sit here and take any more of this. Give him a lie detector test.”36

Diehl was never charged in what the police said was the murder-for-hire plot, though Fischer on January 3, 1985, revoked her bond and ordered her held at the Erie County Prison to await trial. Diehl’s prosecution appeared to be imminent. Fischer scheduled jury selection to start on February 27, 1985, and he made arrangements for the lawyers to pick jurors from a pool of people from outside Erie County. The pretrial publicity, Fischer ruled, was too pervasive for Diehl to get a fair trial before a jury selected from Erie County.

Diehl’s trial would not occur for more than three years. Her case changed course when she changed lawyers. On February 13, 1985, she dropped her two court-appointed lawyers (she got them because she said she had no money, contending all her cash was tied up as evidence) for two lawyers her parents retained. The initial payments were $20,000, for the lead counsel, a meticulous attorney named Leonard G. Ambrose III, and $4,000 for his co-counsel, Michelle Hawk. By the end of Diehl’s case, her parents would pay a total of $60,000 in attorneys’ fees and other costs, such as expert fees, for her defense.37 Ambrose and Hawk would make sure the money was well spent.

While Diehl waited at the Erie County Prison for her case to take shape, another man close to her died. Diehl had no role in the death of Edwin Carey, her paralegal, landlord, and sometime boyfriend, though the authorities made a link between her case and Carey’s suicide on April 3, 1985. He hanged himself inside the house on Sunset Boulevard, where he had been living since Diehl was arrested nearly a year before. Carey, who was black, was sixty-five years old.

Carey suffered from throat cancer, according to the coroner’s report, and he had undergone a laryngostomy, in which surgeons created an artificial hole in his larynx. Doctors at the Erie Veterans Administration Medical Center had told him he would need further surgery.38 One of Carey’s close friends had called police on April 4, 1985, when Carey did not answer his door. The friend told police that he was concerned because Carey had been despondent and had mentioned suicide. The police went inside and found Carey’s body in the darkened bungalow. “The house was completely secured and he had pulled down all of the shades and blinds so that it would be impossible to look into the house,” according to the coroner’s report. “The police had found two handwritten notes in the living room which contained apologies to his family for his actions. We found other handwriting done by Mr. Carey that matched the writing on the suicide notes.”39

Merle Wood, the Erie County coroner, then referred in his report to one of the best-known murder defendants in the county at that time. “Mr. Carey,” Wood wrote, “is the owner of this home and had rented the home to Marjorie Diehl, who allegedly killed her boyfriend Robert D. Thomas in this house [on July 30, 1984].” Wood also wrote that Carey’s close friend “explained that Mr. Carey has been extremely distressed since this murder. He has been the object of much harassment.”40

Diehl-Armstrong remembered Carey fondly throughout her life. A month after his death, while she spoke to a psychologist at the Erie County Prison, she recounted how she was dating Carey at the same time she was seeing Bob Thomas. “Ed recently died through suicide which upset her greatly,” the psychologist wrote.41 More than twenty years later, when on trial in the Pizza Bomber case, she recalled Carey as a “terrific” self-made man who was worthy of her. “Mr. Carey was a very good man,” she said. “I was with him for many years. Edward Alexis Carey. He was a mortician. And he was a very successful man. He was also supervisor of the whole yard at Hammermill Paper Company. He worked there for many years. He also had his own gas station, TV repair shop, and a restaurant.”42 She later described Carey in chivalric terms, speaking about his moral uprightness and devotion to her, and likened Carey to her husband, Richard Armstrong, who died in 1992, “they were like saints to me,” she said.43

Leonard Ambrose had made his reputation as one of the most sought-after defense lawyers in Erie County by his careful presentation and his relentless probing in the courtroom. He also had a deep interest in psychology and psychiatry, which made him an ideal defense lawyer for Marjorie Diehl. His first move was to ask Fischer to declare Diehl incompetent to stand trial. Ambrose argued that her bipolar disorder, unless treated with therapy and medication, would continue to make her so uncooperative that she would be unable to assist in her defense. Ambrose’s request triggered the trial-within-a-trial in Diehl’s already complicated case. The defense and prosecution put the actual trial on hold for years and years as they countered each other on whether Diehl was competent to stand trial in the first place. Ambrose and Michelle Hawk, his cocounsel, challenged whether Diehl had the mental wherewithal to help the defense. The District Attorney’s Office questioned the degree of Diehl’s mental instability while also maintaining that the prosecutors, like Diehl’s defense team, wanted nothing to do with bringing a mentally unfit defendant to trial.

Ambrose had lots of information to help Fischer understand Diehl’s mental state. He got access to all her previous mental health records, including those for her first treatments, at Hamot Hospital, in 1972, plus all the psychiatric reports she filed in her request to receive disability benefits. He also had the condition of Diehl’s house as evidence. Ambrose’s goal was to show that Diehl’s bipolar disorder had made her so uncooperative that she was unable to go to trial without getting medicated for some period of time. Ambrose hinged much of his argument on the finding of the administrative law judge who in January 1984 approved Diehl for disability benefits after finding that she indeed suffered from bipolar disorder. The prosecution contended that Diehl faked or overstated her mental illness so she could get the benefits—an argument that, on its face, was not unreasonable, given Diehl’s willingness to hoard government surplus food and her possessing more than $18,000 in cash despite having supposedly no verifiable income except for the disability benefits. Ambrose wrote to Judge Fischer in June 1985 contending that Diehl’s lengthy mental-health history, plus the administrative law judge’s ruling, should put to rest the prosecution’s “concern that Marjorie’s mental problems developed at or about the time she made application for Social Security Disability benefits sometime in 1982.”44

“The bottom line is Marjorie needs medication,” Ambrose continued in his letter. “Without medication it is the considered opinion of the medical physicians who have examined her that she is simply not competent to communicate in a rational manner with counsel. In reality all we are requesting is that she be afforded her basic fundamental right to medication prescribed by her physicians.”45

Diehl, who had been prescribed Tofranil since 1977, was placed on lithium carbonate, designed to moderate her moods and control her bipolar disorder, on July 3, 1985. The recommendation for lithium came from one of the outside psychiatrists whom Ambrose hired to evaluate Diehl—Robert L. Sadoff, who would also examine Diehl in the Pizza Bomber case. She needed lithium, Sadoff wrote Ambrose in June 1985, because the bipolar disorder “has rendered Marjorie Diehl incompetent to stand trial at the present time because of her inability to communicate effectively with her counsel and her inability, because of the rapid thoughts that bombard her at once during the manic phase, to appreciate her position within this legal situation.”46

While she was on lithium at the Erie County Prison, Diehl continued to undergo more psychiatric evaluations. Her examiners included Sadoff; Gerald Cooke, a psychologist from the Philadelphia area whom Sadoff recommended; and David B. Paul, the Erie County Prison’s staff psychiatrist, who met with Diehl sixty-four times between their first visit, on August 1, 1984, and September 3, 1987, when Paul wrote to Fischer that, based on his continued analysis of Diehl’s mental state, she was still incompetent to stand trial. The reports of the psychologists and psychiatrists mentioned Diehl’s childhood anorexia and the blame she placed on her parents for what she considered a pressured and mostly unhappy youth. The professionals based their findings on interviews with her, but also on more objective sources, like psychological tests.

Cooke administered five tests: the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory, a personality test “indicating test-taking attitude and the nature and degree of psychopathy”; the Rotter Incomplete Sentences Blank, which provides “information on needs, attitudes, values and the quality of interpersonal relationships”; Draw-a-Person, which provides “information on the individual’s self-image and the perception of interpersonal relationships”; Rorschach Inkblot Technique, meant to reveal “unconscious fears, wishes, conflicts, and the degree to which reality is accurately perceived”; and the Weschler Adult Intelligence Scale-Revised/Verbal Subscale, “to estimate intellectual functioning.”47 Based on the test results and his observations, Cooke found that Diehl’s bipolar disorder, particularly her mania, and her underlying paranoia made her incompetent to stand trial at that time, in 1985. Cooke, as the social worker had done in 1972, also focused on Diehl’s troubled relationships with men. He found that Diehl, despite her narcissism, had a poor self-image and needed constant attention, particularly from men, to achieve a sense of self-worth. “Because of her personality features,” Cooke wrote, “she has highly conflictual relationships with others. While she experiences the kinds of angry and negative feelings toward others described, she also has strong needs for attention and nurturance, particularly from men. The result is an approach-avoidance sort of relationship leading to almost continual conflict.”48

Cooke’s evaluation was one of four that professionals performed on Diehl between 1984 and 1987; all four visits yielded the same results—the psychologist and psychiatrists determined that her mental state made Diehl unable to meaningfully and rationally participate in her trial. Faced with such findings, Judge Fischer continually ruled Diehl incompetent to stand trial. The rulings came in 1985, 1986, June 1987, and on September 9, 1987—a significant date in the homicide case against Diehl. Fischer, deciding that Diehl needed more intensive psychiatric treatment than the Erie County Prison could offer, ordered her to the Pennsylvania state prison system’s Mayview State Hospital, outside Pittsburgh, about two hours south of Erie. He ordered the staff at Mayview to perform a psychiatric exam on Diehl at least every ninety days, and to submit the reports to him.

Diehl did not want to go to Mayview; she had written Fischer in June 1987 that she feared she would lose credit for time served in prison if she were transferred to Mayview, which she called a “mental hospital.”49 Diehl in the letter blamed her lawyers for her problems; said she knew what she was doing; and, in what could be considered her understanding of the justice system, mentioned an earlier plea offer that was no longer available—a prison sentence capped at eight to sixteen years in exchange for a guilty plea to third-degree murder, or an unpremeditated killing with malice, in Bob Thomas’s death.50 The District Attorney’s Office in October 1986 withdrew the offer and said it would pursue a conviction for first-degree murder, or a premeditated killing.51 “Some mentally ill people do not recognize that they are ill,” Diehl, commenting on the plea deal and other topics, wrote to Fischer in her trademark scrawl. “This isn’t the case with me. I know that I am manic-depressive and at times have bad pressure of speech and flight of ideas (loose associations). Going to court will not cause me to break. I also know my strengths.”52

Fischer had much support to send Diehl to Mayview. He had two new evaluations from medical professionals that Diehl was incompetent, including a finding from David Paul, who had seen Diehl more than any psychiatrist and perhaps more than anyone other than her lawyers. To help him in his work, Paul requested the other evaluation, by Ted S. Urban, an Erie clinical psychologist. Both were adamant that Diehl, unless rehabilitated through treatment and medication, was mentally unfit to stand trial.

As Cooke did, Urban used a battery of written tests, such as the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory, to help gauge Diehl’s mental state. He never disputed the she was bipolar but found that she only exhibited mania, and no depression, when he met with her. Urban characterized Diehl as a paranoid and unusually self-aggrandizing and manipulative person, a person whose intense self-importance and anger at the world made her susceptible, at any moment, to entering into a kind of emotional fugue state that would foil her ability to cooperate with her lawyers. “Although there was no formal evidence of overt psychotic process,” Urban wrote in his report, in August 1987, “it is my impression that because of the extreme degree of internal conflicts a psychotic loss of control in her perception can be easily triggered.”53

Urban emphasized that Diehl blamed everyone except herself for her problems, including her inability to hold down a job: She was the brilliant intellect with the straight-A’s in high school and the exceptional musical talent, while everyone else was an incompetent who was out to get her. She said the police entrapped her in the case that led to the filing of criminal charges when she worked at the abortion clinic; the police, she said, were working with Hustler magazine and the Mafia on that case. She presented her work history as “essentially successful,” Urban wrote, “and she made no mention of her disability benefits.”54 Urban reported that Diehl told him she left all her jobs voluntarily or was the victim of unfair treatment. “‘Rev. Wards’ wife became jealous’ of her and she was forced to leave,” Urban wrote, quoting his conversations with Diehl. “‘Mr. Locher made passes at me and I left after his wife accused me of having an affair with her husband.’ ‘I was fired after 4 months [from] the Welfare Office because of a personality clash—I dressed much better than her.’”55 Diehl denied using drugs and alcohol, Urban also wrote, but “she subsequently described a relatively protracted relationship with a man with whom she got ‘drunk every night.’”56 But never did Diehl consider herself at fault, Urban wrote. She believed that her needs and comfort and well-being were more important that anyone else’s, and that “if circumstances do not meet with her momentary, fleeting emotional need, her responses work to produce constant distortion.”57 Diehl, in other words, could be nasty and selfish and unbearable, but she was also mentally ill.

David Paul said he also witnessed what he characterized as Diehl’s potentially self-destructive behavior. He wrote Fischer that on July 28, 1987, he sat in on a meeting between Diehl and her lawyers, and listened to her berate them, call them liars, and insist that they were no smarter than a clerk at the prison. He said she called Sadoff, who had previously examined her, a “quack,” and said that some documents she was asked to complete were “foolish.”58 Paul cited Diehl’s bipolar disorder, which he said manifested itself in her hostility toward her lawyers and her inability to control her behavior—traits, Paul wrote to Fischer, that would make Diehl her own worst enemy in front of a jury. Paul wrote:

She has the typical manic’s capacity for terribly poor judgment, particularly in social situations. She will insult and offend people simply because she happens to be feeling that way at the moment and, shortly thereafter, when her mood has changed, feel free to ask favors of them as though the offense she gave had never taken place. Her literality further hinders her in defending herself in a court of law by causing her to feel free to say to jurors that she believes in something like voodoo and astrology . . . , being quite without any understanding of the impression of her that she creates by so doing.

If her attorneys are correct that the way she presents herself in court is of vital importance, in view of her illness and problem with self control and judgment, I feel that she is quite incompetent to stand trial at this time and I do not feel that there is a substantial ability of attainment of competence in the foreseeable future.59

Paul recommended that Diehl receive hospital care to help her recover. And he said her taking lithium carbonate offered a greater likelihood that she would achieve competency.60

Diehl remained combative, but only to a point. She criticized her lawyers at a competency hearing before Fischer on September 4, 1987, at which she also derided the qualifications of another key defense witness—Paul, who she claimed was not board certified. She said nothing was wrong with her, based on her analysis.

I have problems. I’ve tried to live with my problems. I do not try to extenuate my negatives. I try to extenuate the positive. If I was the type of person looking to my lawyers for condolences, I’d probably be like the guy that hung himself in prison because he was so, you know, obviously depressed.

But I don’t let myself get this way and I have some control. I may not have total control over my mood swings and things, I am not going to say I have that, but I have enough control over myself. I’ve proved it with my life. I have proved it. I don’t care what Dr. Paul says. . . . I have proved it with my own life.61

Diehl showed no signs that she understood the absurdity of her argument—that a thirty-eight-year-old woman with a history of mental illness whose house was packed with rotting food and who was awaiting prosecution for murder had full control over her emotions and behavior. Yet Diehl, in an example of her understanding of the justice system, also pleaded with Fischer to make sure that her case would be handled quickly if he were to find her incompetent once more. “Whatever happens,” she said, “I just hope it doesn’t take forever to be resolved, that if I have to go to a hospital, that they give me a chance to be re-evaluated, not leaving me there for three years or something while I am waiting to be evaluated. . . . The reason I want to go to trial is to get the thing over with because it’s hanging over my head. . . . I’m going on my fourth year now in prison.”

“I understand,” Fischer said.62

Diehl went to Mayview. The understanding, based on Paul’s recommendations, was that she would receive medication there. But the kind of medication remained uncertain. Lithium carbonate, which Diehl had started to take on July 3, 1985, had become problematic. The development was unfortunate. Though Diehl initially took the lithium erratically, Paul wrote that she gradually “accepted the idea that medication taking was necessary if she were to have any hope of going to trial and defending herself adequately.”63 To try for further improvement, Paul supplemented the lithium with an anti-psychotic drug, Mellaril (thioridazine). He aimed to have the Mellaril control Diehl’s psychosis, and the lithium regulate her mood swings and maintain and stabilize her personality.64 But the lithium-Mellaril experiment failed, Paul said, so he paired the lithium with another antipsychotic drug, Haldol (haloperidol).65 That combination was more effective, Paul said, but then he had to discontinue the lithium and prescribe only Haldol.

The change came on April 7, 1987. A medical emergency forced it. Diehl had a reaction to the lithium carbonate—she developed severe edema, in which her ankles and feet swelled so much that Erie County Prison’s medical staff grew alarmed. The prison physician prescribed a diuretic to cause Diehl to urinate more frequently and free her body of the excess water. But the diuretic also flushed massive amounts of sodium chloride, or salt, from Diehl’s system, creating a chemical imbalance that posed a hazard. Due to the lack of sodium, the amount of lithium in her bloodstream risked rising to a poisonous level. Paul ordered the lithium stopped. Diehl agreed that lithium carbonate could help control her mania, but she also agreed with the decision to discontinue it. “It was a toxic level with me,” she said.66

Diehl was taking Haldol and the antidepressant Norpramin (desipramine) shortly after she arrived at Mayview State Hospital in September 1987.67 Diehl had been there for thirteen days when her parents drove from Erie to see her. Diehl and her mother and father got into verbal arguments that left Harold and Agnes Diehl—who were paying for their daughter’s legal defense—highly upset.

“[We] won’t be back,” Harold Diehl said.68

Diehl’s anger and obstinacy had become frequent by then, signaling a setback. Though anxious and apprehensive, she had been generally pleasant, even-tempered, and lucid when she arrived at Mayview, whose staff’s immediate reaction was that she was competent.69 Diehl, according to a psychologist, was “working very diligently to maintain a façade of adequacy and control. Because she is eager to get on with her trial and fears that she may be kept in the hospital for a lengthy period she is tending to minimize her problems and weaknesses. She is attempting to present herself in the best possible light and therefore seems to be denying unacceptable feelings and impulses.”70

The façade of self-control started to collapse by the time of her parents’ visit. She continued to speak to her mother constantly on the telephone, but swore at her and used obscene language. Diehl complained of the side effects of her medication, and it was discontinued in late September. “A few days later,” according to a staff psychiatric report, “the patient became agitated and irritable. She then became argumentative, demanding and markedly obsessive-compulsive. . . . At times her behavior became clearly bizarre.”71 As an example, the Mayview staff placed Diehl under close observation after she was found to have caused herself to vomit in the bathroom. Diehl also became extremely preoccupied with her personal appearance, and spent long periods of time in the bathroom putting on makeup. She was increasingly rude, belligerent, and demanding with the staff, and had to be reminded repeatedly to follow the rules.72

Her compulsive and excessive behavior increased in October and November, particularly about her cleanliness and personal hygiene. This was the period when the staff at Mayview found that she had to brush her teeth as many as thirty-two times as part of a cycle.73 “At the beginning of November,” according to the psychiatric report, “she became increasingly grandiose and paranoid and there was rambling and pressured speech as well as loosened associations. Reasoning and judgemental capacity became markedly impaired. At that point it appeared she did indeed have Bipolar Affective disorder, mixed type.”74 The stress of her case clearly was affecting Diehl’s mental stability. On November 9, 1987, the Mayview staff found her incompetent. Fischer accepted the report, and ordered Mayview to evaluate Diehl again within ninety days.

The staff in early November also placed Diehl on a new drug for her—Tegretol (carbamazepine), an anticonvulsant used to treat bipolar disorder. David Paul had told Judge Fischer at the competency hearing, in September 1987, that Tegretol someday could be used to help control Diehl’s moods,75 and the staff at Mayview found Tegretol effective. While she was on the drug in mid-November 1987, the staff started Diehl “on a highly structured and rigid behavior program to help her overcome her obsessive-compulsive behavior and aid her in compliance with ward regulations and routines.”76 She also participated in regular individual and group psychotherapy, which added to her improved behavior while she was on Tegretol.77 As with the other drugs, however, Tegretol proved problematic for Diehl. It created severe side effects, including a rash and edema—the same condition that led Paul to order her off the lithium carbonate while Diehl was at the Erie County Prison. The staff at Mayview discontinued the Tegretol for Diehl in mid- to late December 1987. In January 1988, Diehl refused to take any medication. She cited the “unbearable side effects” the other drugs had caused her.78 Mayview, under the law, could not involuntarily drug Diehl.79

About six week later, a period during which she took no drugs, the authorities at Mayview found Diehl competent to stand trial. They made their finding on January 29, 1988. It came in a report from a psychiatrist at Mayview, Duncan Campbell, and a psychologist, Howard P. Friday, the hospital’s acting director of its regional psychiatric forensic center. They determined that Diehl’s physical disorders were few—an apparent jaw injury, which she said was from an accident from years before; and allergies to antipsychotic medication. In terms of Diehl’s mental state, Duncan and Friday determined that Diehl’s bipolar disorder was “in remission,” though she was no longer on medication.80 “For the several weeks that have followed discontinuation of medication,” they wrote, “she exercised good controls and was essentially cooperative and appropriate in her interactions. She has remained involved in her individual and group therapy as well as a variety of other activities here. She has had an opportunity to discuss her conflicts with the family, her attorneys and other important individuals in her life and she appears to have developed some degree of insight into the part she has played in these difficulties. It is felt that at this juncture . . . the patient is now competent to be tried and should be returned to [the] Erie County Prison.”81

The third edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, or DSM-III, published in 1980, came into play, as Campbell and Friday used its multiaxial classification system to summarize their diagnosis of Diehl. They referred to three axes: Axis I, for clinical syndromes; Axis II, for personality disorders and specific developmental disorders; and Axis III, for physical disorders. Duncan and Friday wrote of Diehl:

Axis I: Bipolar affective disorder, mixed type, in remission.

Axis II: Mixed personality disorder with paranoid and narcissistic features.

Axis III: Multiple allergies, including allergies to Tegretol and lithium and temporomandibular joint disease.82

The report noted that drugs had helped. Campbell and Friday acknowledged that lithium carbonate and Tegretol had “some calming effect” on Diehl, and they called her severe reactions to the drugs regrettable. They did not eliminate the possibility that Diehl would need drugs again. They all but predicted Diehl’s remission would end and her bipolar disorder would dominate her behavior once more. “It is certain,” Campbell and Friday wrote, “that this individual will under stress have increasing problems with control and mood and in spite of her concerns about side effects from other psychotropic agents, she may require these at times to control symptoms of her Bipolar Disorder. Undoubtedly, she may require them periodically under the normal course of this illness.” Campbell and Friday concluded: “The prognosis certainly must be guarded. This illness will manifest itself again.”83

Diehl’s lead lawyer, Leonard Ambrose, offered a more blunt analysis in his review of Campbell and Friday’s report. He faulted them for failing to consider whether Diehl’s present mental condition allowed her to cooperate with him (Ambrose said it did not). And even by the report’s admission, Ambrose maintained, Diehl’s behavior was unpredictable: “The catalyst is stress,” Ambrose wrote to Judge Fischer. “In essence,” he wrote, “the report paints the picture of a person who is a literal time bomb waiting to go off.”84

Fischer accepted the Mayview report on February 17, 1988. After two years of reviewing psychiatric reports on Marjorie Diehl, he found her competent to stand trial.