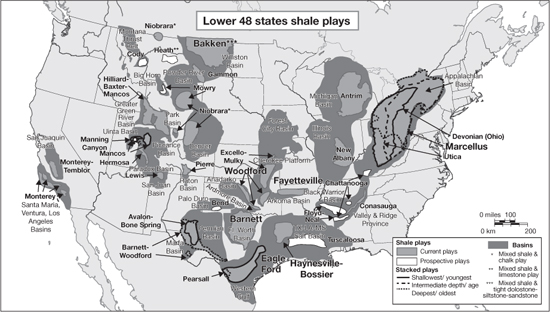

As mentioned, the purpose of hydraulic fracturing is to access natural gas and oil trapped in shale formations, also known as “plays.” Shale plays are found across the United States and around the world, including in large deposits in South America and China, where hydrofracking is only in the experimental stage at the moment.

The United States’ most famous and productive shale play thus far is the Barnett Shale, which spreads for 5,000 square miles around Fort Worth, Texas, and provides 6 percent of the nation’s natural gas.1 (The Barnett is where Mitchell Energy perfected slickwater fracking.) Since 2005, thousands of people who live on top of the Barnett have leased their land to drillers and become wealthy. By 2008, landowners in the southern counties earned bonuses of $200 to $28,000 per acre, with royalties ranging from 18 percent to 25 percent (one lease in Johnson County was permitted for 19 wells).2 But the Marcellus Shale, which spreads beneath five states in the Northeast, is thought to be from two to four times the size of the Barnett, and home to the world’s second-largest gas deposit after the South Pars field, beneath Qatar and Iran.3 Development of the Marcellus Shale has only just begun. Range Resources, based in Fort Worth, Texas, has worked both plays: in 2011, it sold off all of its holdings in the Barnett Shale and invested the $900 million of the proceeds in the Marcellus. “Barnett is a good play, but the quality of the rock and economics don’t really complete with the Marcellus,” said Range CEO Jeff Ventura.4

Energy Information Administration

While there are numerous plays spread out across the country, the top few represent the majority of land and have attracted the largest drilling and development investment, which totaled more than $54 billion in 2012.5 These plays are focused on oil or liquid gas, with the exception of the Marcellus, where the majority of wells are dry gas completions. (As mentioned in the fossil fuel primer in chapter 1, “dry” gas is pure methane.)

The major plays in the United States include the following:6

Anadarko-Woodford: Located in west-central Oklahoma, this play runs through the Anadarko Basin, at some 11,500 to 14,500 feet deep. It contains crude oil and liquid gas, and the average cost of drilling and completing a well there was $8.5 million in 2012.

Bakken: Covering some 200,000 square miles beneath parts of Montana, North Dakota, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba, this organic-rich, low-permeability formation contains the largest known oil reservoir in the continental United States: an estimated 3.6 billion barrels of oil, 1.85 trillion cubic feet of natural gas, and 148 million barrels of natural gas liquids, according to the US Geological Survey. The play is relatively thin and runs from a depth of 3,000 feet to 11,000 feet deep. For years it was considered uneconomical to drill there, but with the advent of modern fracking this resource trove set off the legendary “Bakken boom,” which enriched North Dakotans and brought people from across the country to one of the biggest oil discoveries of recent years.

Barnett: Situated directly beneath the Dallas–Fort Worth metroplex, the Barnett holds some 360 trillion cubic feet of natural gas, and represents one of the biggest shale gas plays in the country. The Barnett is known as a “tight” gas deposit, where the rock is very hard, permeability is low, and the extraction of natural gas is difficult. The combination of horizontal drilling and hydrofracking opened up the Barnett in the late 1990s. Today, with 13,000 wellbores reaching maturity there, companies like Halliburton—which has drilled over 10 million feet of horizontal wells, and fractured and refractured wells in the Barnett—are exploring the region’s nooks, crannies, and edges for gas reserves and untapped oil deposits.

Eagle Ford: stretching some 400 miles long, this play underlies southwest and central Texas. The shale here dates to the Upper Cretaceous period, and is brittle (which is good for fracturing). The shale formations occur as a wide sheet some 40 to 400 feet thick, at depths of 4,000 feet to 14,500 feet, and contain oil and some 150 trillion cubic feet of dry and wet natural gas.

Fayetteville: Located in the Arkoma Basin in Arkansas, this is the nation’s second-most-productive shale play (after Haynesville, below), is among the United States’ 10 largest energy fields, and holds some 20 trillion cubic feet of gas. The Fayetteville covers some 4,000 square miles, ranges in thickness from 60 to 575 feet, and runs from 1,450 feet to 6,700 feet deep.

Granite Wash: A group of plays in the tight sand beneath north Texas and south Oklahoma, where layers of minerals were deposited by ancient streams and washouts. Here a number of oil and gas formations are 1,500 to 3,000 feet thick, and are stacked at 11,000 to 15,000 feet deep.

Haynesville: With 5.5 billion cubic feet of natural gas recovered from the play every day, Haynesville contains an estimated 250 trillion cubic feet of gas, and could surpass the Barnett Shale to become the most productive shale play in the United States. Rich in organic fissile black shale of the Upper Jurassic age, it is located on what is called the Sabine Uplift, which separates the salt basins of east Texas and north Louisiana. The play covers 9,000 square miles, and, running at depths of 10,000 to 14,500 feet, it is far deeper than most plays. Average wells are at some 12,000 feet deep. As a result, temperatures and pressures here are intense: the temperature at the bottom of the well averages 300 degrees Fahrenheit, and pressures at the wellhead exceed 10,000 pounds per square inch.

Marcellus: As noted earlier, this play is located in the Northeast, the biggest gas-consuming region of the country, and was first developed in 2004. For now, most of the Marcellus gas wells are in Pennsylvania, which has aggressively promoted hydrofracking. The wells there average about 6,200 feet deep and cost roughly $5 million each. By contrast, neighboring states have been more cautious to exploit the Marcellus. New Jersey and New York have temporarily banned hydrofracking, pending the results of lengthy environmental and health reviews. The Marcellus is a natural gas shale stacked on top of another major play, the Utica Shale, which contains oil (see below).

Monterey Shale: Running southeast of San Francisco, this formation covers about 1,750 square miles, from southern to central California. The federal EIA estimates that it holds more than 15.4 billion barrels of oil in shale deposits that are estimated to be 1,900 feet thick and lie at an average depth of 11,000 feet. If the estimates prove accurate, that would mean the Monterey contains four times as much tight oil as the Bakken Formation, and approximately 64 percent of the nation’s shale oil reserves. If exploited, the Monterey’s tight oil could yield 2.8 million jobs and $24.6 billion in state and local taxes, boosting California’s economy by 14 percent by 2020, according to a recent study from the University of Southern California. But with complex geology that is prone to earthquakes, disappointing early production numbers for wells, a lack of water, and strong environmental opposition, widespread hydrofracking in California is not a given. (This region has long been commercially exploited by conventional oil drillers, and is the nation’s third-highest oil producer, after Texas and North Dakota.)

Niobrara: This emerging oil and gas play lies near the Rocky Mountains beneath northeastern Colorado, Wyoming, Nebraska, and Kansas. Made up of Cretaceous rock, the Niobrara deposit measures between 150 to 1,500 feet thick and lies about 6,200 feet deep. Though exploitation is still in its early stages, the Niobrara’s brittle, calcareous chalk is well suited for hydrofracking, and it is considered a potentially huge play. Most production is focused on the northeastern corner of Colorado, in the Denver-Julesburg basin.

Permian Basin: Extending 300 miles long and 250 miles wide and located under New Mexico and west Texas, the Permian has been drilled for oil with conventional rigs since 1925. The formation is filled with Paleozoic sediments, and has one of the world’s thickest rock deposits from the Permian geologic period (dating to some 290 million years ago). Today this play is undergoing a renaissance thanks to hydrofracking. It has been estimated that the Permian Basin is rich, with a single formation—the Spraberry—holding 500 million barrels of unconventional oil and five trillion cubic feet of natural gas.

Utica Shale: Lying 3,000 to 7,000 feet beneath the Marcellus Shale, the Utica formation is one of the largest natural gas fields in the world. Stretching from Quebec and Ontario in Canada down through New York, Pennsylvania, Ohio, and West Virginia, it also underlies parts of Kentucky, Maryland, Tennessee, and Virginia. The Utica play is estimated to hold some 1.3 to 5.5 billion barrels of oil and about 3.8 to 15.7 trillion cubic feet of natural gas. The Utica Shale is organic-rich calcareous black shale dating to the Late Ordovician period (460 million years ago). It has a high carbonate content and a low clay mineral content, making the Utica rock more brittle than the Marcellus Shale. This requires different hydrofracking strategies and makes Utica wells more expensive to develop than those in the shallower Marcellus formation. Experts consider the Utica “a resource of the distant future.”

Woodford: Lying beneath most of Oklahoma, the Woodford Shale has complex mineralogy and geology, which makes drilling a challenge. This play has produced oil and gas since the 1930s, and the first horizontal wells were drilled there in 2004. Today, some 2,000 wells are in production there, including over 1,500 horizontal wells.

In spite of the riches buried in the shale plays listed above, hydrofracking can be geologically, technically, and economically challenging. But an even greater obstacle might be citizen and environmental opposition to the controversial process. While advances in drilling techniques and the types of chemicals used have dramatically changed the scenarios for fracking, lawsuits have challenged the Bureau of Land Management’s leasing of federal lands to energy companies.7 Concerns about hydrofracking’s impact on global warming, endangered species, wildlife habitat, farm animals, and food supplies have spurred environmental groups to action. And citizens’ fears about the impact of industrial processes, truck traffic, and the social impact on rural communities have led several states, and individual towns, to seek bans on fracking. I will discuss this at greater length in chapter 6, but in the context of where hydrofracking is allowed, it is instructive to see where it is not.

In June 2011, New Jersey became the first state whose legislature passed a moratorium on hydrofracking, in a 33 to 1 vote.8 In January 2012, Ohio lawmakers placed a temporary ban on hydrofracking after a panel of experts argued that the process of storing used fracking fluid, or “flowback,” was to blame for creating massive sinkholes and an outbreak of earthquakes—including a 4.0-magnitude temblor that hit on New Year’s Eve 2012.9 In May 2012, Vermont became the first state to ban hydraulic fracturing outright. “This is a big deal,” announced Democratic governor Peter Shumlin. “This bill will ensure that we do not inject chemicals into groundwater in a desperate pursuit for energy.”10

In Colorado, the city of Longmont (population 88,000) banned hydrofracking in 2012, and was promptly sued by Governor John Hickenlooper—who believes that hydrofracking fluid is so harmless that he reportedly drank a vial of it in public. “The bottom line is, someone paid money to buy mineral rights under that land. You can’t harvest the mineral rights without doing hydraulic fracturing, which I think we’ve demonstrated again and again can be done safely,” Hickenlooper countered.11 In defiance of the governor, the city of Fort Collins (population 147,000) banned hyrdofracking in March 2013. Both the governor and the Colorado Oil and Gas Association have threatened to sue the city.12

Significant shale plays have been identified around the world, from Australia to India to Russia, but for now commercial hydrofracking is only taking place in the United States and, to a lesser extent, Canada. There are several reasons for this. First, the process was developed in America, which is now years ahead of every other nation in research, development, and use of fracking techniques. Second, favorable conditions in the United States have allowed fracking to spread quickly. The Council on Foreign Relations has identified seven critical “enablers” of the American shale boom: some are essential, such as resource-rich geology; others are catalysts, such as favorable land and mineral laws, which spurred the production of shale gas in the United States and Canada.13

Thanks to the recent glut in shale gas, the United States has started to export natural gas abroad. Now the export of technical and financial know-how is beginning to follow suit, though it will take other nations years to build up the infrastructure necessary for efficient shale oil and gas programs of their own.

Many countries are building pilot programs and experimenting with hydrofracking methods. Western Europe, the US EIA estimates, has some 639 trillion cubic feet of shale gas resources, which is more than four times the reserves of the Marcellus Shale.14 Hydraulic fracturing was conducted in Germany, Holland, and the United Kingdom in the 1980s. In 2012, Cuadrilla Resources, a UK shale-gas explorer, calculated that its license area in Lancashire contains some 200 trillion cubic feet of natural gas, and estimates there is more shale gas in the UK than the entire reserves of Iraq.15 (The UK uses roughly 3 trillion cubic feet of gas per year.) As Italy, Poland, and Lithuania build terminals to receive liquefied natural gas (LNG) tankers—long ships outfitted with distinctive spherical tanks—imports to the EU are estimated to grow by 74 percent by 2035.16

Eastern Europe’s interest in hydrofracking has a political subtext. The first hydraulic proppant fracturing was carried out in 1952 in the Soviet Union, while Ukraine, Poland, and Mongolia are planning to tap shale basins, both for economic reasons and as a way to reduce their energy dependence on Russia, with whom they have had a fraught history.17

As for Russia itself, Vladimir Putin is eyeing America’s shale boom with a mixture of deep suspicion and growing interest. Energy companies account for half the value of the Russian stock market, and their revenues help to prop up the government. Gazprom, the state-backed energy company with a monopoly on natural gas exports, has long used its dominance to get its way: Russia cut off natural gas to Ukraine twice, in 2006 and 2009, when contract negotiations grew heated. But as America uses its shale reserves to become the world’s biggest gas producer and a likely gas exporter, the balance of power is shifting. America’s gas glut is depressing prices on the world market, and sending unneeded gas from the Middle East to Europe. Bulgaria recently negotiated a 20 percent price cut in its new 10-year contract with Russia.18

Alexey Miller, the Gazprom boss, says, “We are skeptical about shale gas,” and has derided the gas boom as a “myth” and “a bubble.” But Gazprom is in trouble: its 2008 market capitalization of $367 billion had shrunk to a mere $78 billion five years later.19 Putin—who once complained that shale gas costs too much and that fracking harms the environment—now says that there might be “a real shale revolution” after all, and that Russian energy firms must “rise to the challenge.” Rosneft, the country’s largest oil producer, is working to double its share of the Russian gas market by 2020, and might even try hydrofracking shale beds. As it turns out, geologists believe that Russia has enormous shale oil and gas reserves, which could one day supply both European and Asian markets.

In Asia, China is the world’s biggest energy user and is estimated to have as much as 25 trillion cubic meters of shale gas reserves, 50 percent larger than US reserves.20 China established a research center in 2010, drilled its first horizontal shale well in 2011, and has targeted the production of 30 billion cubic meters a year from shale. India is also thought to have significant shale gas reserves, far more in fact than the 38 trillion cubic feet that the EIA has officially estimated. In a 2013 speech at Pace University, Veerapa Moily, India’s minister of petroleum and natural gas, described how his government is planning an aggressive push to extract shale gas from its large deposits.21

As in the United States, hydrofracking has not always been greeted with open arms elsewhere. France—an enthusiastic supporter of nuclear power, another controversial energy source—sits above the largest estimated reserve in Western Europe. But in 2011, after winemakers and environmentalists concerned about water and pollution pressured the government, France became the first nation to ban hydraulic fracturing outright.22 In January 2012 Bulgaria joined the French, withdrawing a hydrofracking license granted to Chevron Corporation, after hundreds of protestors marched to the capital, Sofia, because of concerns about water and soil pollution in the nation’s most fertile farming region, Dobrudja.23 Other countries have placed a temporary moratorium on the practice, such as Czechoslovakia and Romania, pending legislation that eliminates legal risks. The United Kingdom also temporarily suspended hydrofracking, after two small earthquakes rocked Lancashire in northwestern England, but the ban was lifted in 2012.24

The lack of fracking in other countries is not simply due to public concerns. In Western Europe, for example, there is so little geological data about shale regions that in many cases it remains unclear how much gas is there and whether it can be extracted profitably. In 2012, ExxonMobile canceled plans to frack in Poland, after two test wells proved to be uneconomical.25 Chevron also has a stake in Poland, but is proceeding “very cautiously.”

In mid-2013 Germany was researching and debating the merits of hydrofracking. Peter Altmaier, Germany’s environment minister, says the process should be banned near drinking water supplies. Yet Germany also has plans to phase out nuclear power generators completely, a decision that is sure to make natural gas “a bigger part of the energy mix,” says Daniel Yergin, the noted American energy analyst.26