NOT LONG AFTER CARLOS DELUNA’S ARREST FOR CAPITAL MURDER, his mother, Maria Margarita Martinez, became ill. According to her daughters, she’d always been a healthy woman, but her youngest son’s arrest brought on kidney problems and other complications. Doctors operated on her three times. Two weeks before Carlos’s trial was set to begin, heart problems developed, and she went into intensive care.

Margarita was supposed to be Carlos’s star witness, but the judge wouldn’t postpone the trial until she was well enough to testify. Margarita clung to life while the trial went on, with her daughters shuttling back and forth between the hospital and the courthouse. She died two weeks after the trial ended, at age sixty-one.

Margarita had ten children, the first of whom was born when she was only thirteen. According to family lore, she left the father of her first six children, Francisco Conejo, after she couldn’t take the beatings anymore. At the time, Becky, the youngest of the six, was just a baby.

In the 1950s, Margarita moved her family from San Antonio to the La Armada housing project in Corpus Christi. Her children remember the “Mexican projects” as not so bad back then. Everyone was poor, but they didn’t know any better and were thankful for a place to live. The government kicked in part of the rent and sent Margarita a check once a month for groceries and school clothes. The older children remember her working hard to raise them herself and be “like a mother and dad to all of us.”

After moving to Corpus, Margarita started seeing Joe DeLuna. Joe made a decent living hauling scrap metal to Mexico and selling it. Within a few years, they had three children together—Manuel in 1961, Carlos on the Ides of March in 1962, and Rose in 1963. Joe and Margarita never married, and Joe carried on a relationship with another woman that produced three sons. He left Margarita when she was pregnant with Rose.

Rose DeLuna Rhoton is the family historian. In a conversation at a North Houston McDonald’s in 2004, and in several that followed, she shared what she knew with the investigators looking into her brother Carlos’s case.

According to the stories Rose heard, her mother first caught the eye of the much younger Joe DeLuna in a bar soon after moving to Corpus Christi. From then on, she hid her age from Joe. He walked out for good, the story goes, when he found out that she’d lied to him—that she had six children by Conejo, not the four still at home. The two eldest boys were already grown.

Rose heard that her father, Joe, was a “momma’s boy” and that his momma thought he was too good for Margarita. The older siblings remembered Margarita and Joe fighting all the time.

Rose, short for Rosemary, was named after her grandmother Rose DeLuna and her mother Maria Margarita. She never met her grandmother and namesake, though, or her father. She heard that Carlos once went over to their grandmother Rose’s house looking for his dad, but the old lady sent him away. She didn’t want to have anything to do with her grandson or any of Joe’s other children by Margarita, and Joe never did either.

None of the Conejo or DeLuna kids knew the father of Margarita’s tenth child, or the baby boy himself. “She gave him away,” Rose told the investigators. “So I never met . . . that brother. [But] she did keep us three.”

When Rose was about four years old, Margarita met Blas Avalos, and the two were soon married. Rose rated Blas “okay” as a stepfather. Every once in a while, he’d spank one of them, but only when Margarita made him do it. It wasn’t in his nature to hit them, Rose believed. Mostly, Blas stayed on the sidelines.

Blas’s big problem was his drinking. Rose called him a “weekend alcoholic.” Starting on Friday night, after he came home from his job laying asphalt, and through Sunday night, Blas would drink at home or at an older neighbor’s house nearby. “The two of them would just sit and drink until they passed out,” Rose recalled.

Rose understood why her mother let the tenth child go. Her mom was already too exhausted to raise her second set of kids. As Carlos DeLuna himself wrote to a news reporter in 1989, briefly describing his childhood, “My mother she was 40-years-old when she had me. And she was old, and I guess she was tired of raising kids.”

The job of rearing Manuel, Carlos, and Rose fell to their three older half-sisters. Each older girl took responsibility for one of the DeLuna kids—dressing them, feeding them, and buying them clothes. Vicky Conejo chose Manuel, Mary picked Carlos, and Becky took Rose.

When the older girls were dating, they couldn’t leave the younger kids home and had to bring them along. Mary Conejo Arredando laughed when she described the arrangement years later. It wasn’t so bad, she said. She liked taking Carlos. He was a “good boy”; he behaved.

Margarita also made the older girls get jobs while they were in junior high and high school. At “paycheck time,” Vicky recalled, “we would buy [the younger kids] . . . clothes. That’s the way we were raised. . . . [E]very paycheck, we had to go buy something for our brother . . . like he was our responsibility.” The rest of the paycheck went to Margarita to help with the rent.

Margarita wanted the older girls to stay home from school to look after the younger kids, as well as hold down paying jobs. The principal and teachers tried to get after Margarita about this, but she ignored them. Mary recalled being summoned to the principal’s office and asked why she was absent all the time. She explained that her mother needed money and had to work outside the house. Someone had to stay with the littlest children. The school gave Mary a job in the school cafeteria, but her sister Vicky quit school to be at home with the DeLuna kids.

. . .

For eight of the nine children she raised, Margarita viewed her role as a parent in a narrow and practical way: get them to a point where they could take care of themselves and send them on their way. She loved them, Vicky said, but once they could support themselves, her job was done. Rose remembers a home without love, hugs, or “good mornings.” Her mother just wanted the kids grown and out of the house. It didn’t bother her that Vincent, the oldest, left as a teenager and never came back. Margarita was just happy that he could get along on his own.

Becky, the youngest of the Conejo kids, got pregnant when she was fourteen, a year older than her mother had been when Vincent was born. Margarita had no sympathy. Her attitude was, “Hey, I didn’t tell you to get pregnant,” so Becky left home.

Manuel, the oldest of the three DeLuna children, quit school when he was in junior high and left home after that. He followed his half-sister and surrogate mom Vicky Conejo Gutierrez to Garland, Texas, near Dallas, where she and some of the other half-siblings had moved with their young families to work in a Kraft Foods plant. Manuel traveled back and forth between Garland and Corpus Christi, and in and out of trouble with the law—starting with a car theft as a teenager that ended when he backed the vehicle into a police cruiser at the Casino Club and tried to flee the scene.

Rose was still little when Becky, her surrogate mom, left. The other girls had married and left home by then, so it fell to Rose to cook and clean for her older brothers. It was “normal [for] the Mexican generation,” Rose explained, that the mom was harder on the girls than the boys. Rose and her sisters had to do exactly as they were told or they “got the crap beat out of [them].” Manuel and Carlos did “pretty much . . . whatever they wanted.”

Rose recalled getting up at 4:00 A.M. If she wanted to go to school, she had to make sure the house was cleaned and breakfast was made for the boys. When school got out, she had to go straight home to make dinner and finish cleaning. Rose started running marathons when her own children got older. She always felt bad that she wasn’t allowed to participate in sports after school. She pointed out that Margarita had no problem when her two sons joined the football team in junior high.

School was an annoyance for Margarita because it meant extra expenses for clothing and supplies. The only reason she let the kids go to school, Rose said, was “the . . . [law]. If that law wasn’t in place, we wouldn’t be going to school.” After Blas came on the scene, the family moved to a tiny house in a new subdivision. The move made it harder for Rose and her brothers to get to school—they had to take a city bus to the school bus stop, and then another bus to school.

“You have to understand,” Rose explained, Margarita herself “never went to school.” She couldn’t read or write, or speak any English. She worked her whole life cleaning people’s homes. “I don’t blame her,” continued Rose. “That’s just the way she was brought up.” For “a lot of old generation . . . Mexicans, that’s how it [was]. You don’t go to school. . . . When you are old enough to get a job you should be out . . . working.”

. . .

For Carlos, however, Margarita was a different kind of mother. All her other kids noticed it. “Oh, God, she loved Carlos,” Vicky recalled. “He was her pride and joy. She would do anything for Carlos, anything.” He was her favorite, her “consentido.” “I don’t know why,” Vicky said, but for Carlos her mother’s love “was more.”

Some of the siblings thought that Margarita cared more for Carlos because he looked like his handsome father, Joe. Vicky believed that it was a mother’s nature to defend a child who couldn’t seem to stay out of trouble.

But Rose, who was closest in age to Carlos, knew that it was something else. More outspoken than her siblings, Rose came right out and asked her mother. Carlos was always doing things he wasn’t supposed to do. Why didn’t she get mad and hit him like she did the others? Why was it that any time he messed up, she was there, helping him?

Margarita’s answer weighed on Rose, another burden to shoulder for a mother too worn out to bear it herself anymore. Margarita believed that there was something wrong with Carlos. She told Rose that Carlos was like a “little bird with [a] broken wing. The other little birds can take care of themselves; they’ve flown out of the nest. . . . I don’t have to worry about them.” But this one couldn’t make it on his own.

“My mom raised nine kids,” Rose explained. “[W]hen you have that many kids . . . you know [when] there’s something wrong with one.” Although Margarita was too uneducated to know how to say it, Rose believed her mother could see that “Carlos had a disability.”

“He was slow,” Rose said reluctantly, shying away from more clinical words. “My mom . . . knew that he was slower than the others. . . . She knew he wasn’t learning the way he should be.”

“Could [Carlos] talk to you like we’re talking right now?” Rose asked. “Yes. If you look at him and talk to him, do you think there is something wrong with him? No.” And when it came to manual work, Carlos could watch you do something and pick it up, she said. But if you gave him a task where he had to make sense of something he read or heard, then “you would see he had an issue.” He “couldn’t do it.”

That’s why Margarita paid more attention to Carlos than the others—“always getting him out of the situations that he got himself into. Because she knew he had an issue.” And “that’s what killed my mom,” Rose believed. That’s why she “gave up” and died, because she “let Carlos down.” She didn’t help him in his greatest hour of need.

Rose explained. Shortly before Wanda Lopez was stabbed, Carlos had called home from a skating rink and bowling alley a mile from the Sigmor Shamrock gas station to ask for a ride home. By then, the other children had moved out, and it was just Margarita and Blas. Carlos had moved in only a few weeks before, on parole from prison. Blas got Carlos a job at the paving company he worked for, but beyond that he and Margarita weren’t used to taking care of a twenty-year-old. Only an hour before Carlos had called, they had dropped him off at the skating rink. Now he wanted to come back home.

But it was Friday night, and even before taking Carlos to the rink, Blas had started drinking. When Carlos called for a ride home, his stepfather was too far gone to take the car out again. Margarita demurred as well. She couldn’t see well at night and didn’t want to drive by herself.

As Blas testified at Carlos’s trial, Margarita told Carlos to find a ride home or use the pay he received earlier that day to get a cab home. Carlos had been counting on Margarita, not his barely communicative stepfather, to be his star witness at trial: to explain to the jurors that her son, begging for a ride home, a week’s pay in his pocket, wasn’t bent on robbing anyone.

But Margarita didn’t testify. Maybe if the judge had postponed the trial, she could have dragged herself out of the hospital and into the courtroom, but Rose wasn’t sure.

Her mother “didn’t know how to get [Carlos] out of it,” Rose told the investigators. “If she could, she would.” Carlos had called her to pick him up from the skating rink, and Margarita “blame[d] herself for that, for not going out there and trying to get him. . . . She believe[d] she let him down.” It was after that, Rose continued, that her “mom gave up.” She “was tired, and she gave up.”

Even after he was arrested, Carlos couldn’t reach his mother to tell her. He called his oldest half-sister, Toni Peña, and told her that “he had been arrested, and they were not going to let him go.” Toni told the investigator that “[h]e did not seem to understand what had happened to him.”

If Margarita “would have just went for him,” Rose reflected. “If she would have just got in that car and went and picked him up [at the skating rink], he would not have been in the situation that happened.”

“That’s what killed my mom.”

. . .

For a long time, Rose admitted, she, too, blamed Margarita. And she blamed herself.

“I believe it was in February of ’83 that they claimed that Carlos committed this crime,” Rose recounted for the investigators. “My mom passed away in August of ’83.” Rose saw Margarita just before she died. She asked Rose one thing. “I want you to do something for me,” Margarita told Rose. “Promise me that you’ll always look out for Carlos. Promise me that.”

“I told her, ‘Okay, I’ll look after him,’” Rose said. She knew that her mother asked her and not any of the other siblings because Carlos was especially close to her.

A precise and dignified woman, Rose is not given to shows of emotion. But when she recalled the promise she had made to her mother, she broke down and cried. “I couldn’t help him,” she sobbed. “I did not know how to help him. . . . And I blame myself.”

. . .

Rose believed her brother when he told her and others in the family that he hadn’t killed Wanda Lopez. “My brother Carlos could not do such a crime,” Rose told the investigators firmly. “Could he steal? Yeah, he stole. Could he do drugs? Yeah, he did drugs. I know all that. But he could never . . . kill anyone.”

“Growing up as kids,” she explained, “my brother was afraid of the dark. That tells you something. . . . He was afraid of the dark.”

“[Carlos] and I had a paper route,” she recounted. “We rolled up papers and we would go throw them out early in the morning.” On their morning route, there was “a Chihuahua [dog] this big,” Rose said putting her hands about a foot apart. And Carlos “was afraid of that Chihuahua. . . . Thirteen-year-old boy afraid of a Chihuahua this big. So I know my brother couldn’t commit such a crime I know dead in my heart that he couldn’t commit such a crime. . . . And I feel horrible that I could not help him in any way.”

All the siblings were shocked when they heard about Carlos’s arrest for murder. They knew he’d been a wild teenager, but they couldn’t believe he’d knife a woman to death. Carlos’s half-sisters remember him as a good kid—“well behaved,” in Vicky’s recollection, “gentle and loving,” in Mary’s.

Rose remembered Carlos as “a follower. Carlos followed people.” If one of the DeLuna siblings was up to no good, it was Carlos’s older brother, Manuel. Manuel was always the instigator, and Carlos did what Manuel said.

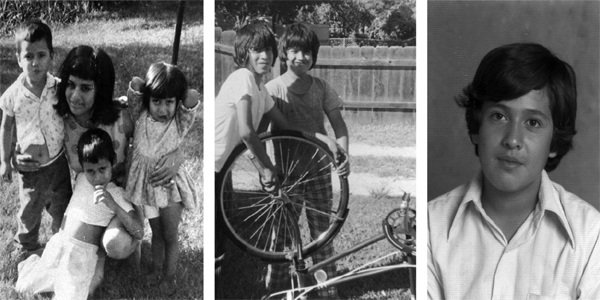

One Christmas, Margarita bought bicycles for Manuel and Carlos (figure 5.1). Soon after, off Carlos went on his bike, following Manuel, who said he would lead them from their Gulf Coast home to North Texas, where their older brothers and sisters lived. They were quickly caught and punished by the authorities for skipping school.

That was Carlos, Rose recalled: doing whatever Manuel said—including taking the rap when his older brother misbehaved. Manuel would blame Carlos, Rose explained, and her younger brother would never defend himself. “It was always Carlos taking the blame for Manuel,” agreeing that he was the one at fault. Although not one to admit his own failings, Manuel agreed with his sister about Carlos. “My brother was not a leader,” he told the investigators, “he was a follower. He could be brainwashed to do anything.”

FIGURE 5.1 The DeLuna children in the 1970s: (left, clockwise from top left) Manuel, Mary Conejo, Rose, and Carlos; (center, from left) Carlos and Manuel; (right) Carlos.

At Carlos’s trial, the prosecution called Eddie Garza, the celebrated Corpus Christi police detective, to testify that Carlos had a “bad character” as a teenager. Garza worked the city’s Hispanic neighborhoods and knew all the troublemakers. Rose despised Garza for what he said about her brother at the trial. But Garza’s assessment of Carlos in an interview at his detective agency years later was not so different from Rose’s.

Garza remembered Carlos as “a slow thinker,” not completely retarded, “he wasn’t that. He was just a slow thinker, a follower, not a leader.” He was someone whom the others “would tell . . . ‘Go do this’ or ‘Go do that’ and the guy would follow what someone else told him. He wasn’t a person that would stand up and think on his own what he was going to do.”

Carlos’s elementary-school teachers referred him to Special Services for evaluation because he was so far behind in class. A sixth-grade teacher wrote, “He can read but can’t comprehend. He is lost on abstract concepts such as fractions. He does pretty well one-to-one but can’t function in even a small group. His attention span is extremely short.”

Medical and psychological tests revealed that the twelve-year-old had a “language learning disorder.” He had the mental functioning of a ten-year-old, the expressive vocabulary of an eight-year-old, and the small motor coordination (for “pencil and paper tasks”) of a child “between 7-1/2 and 8-1/2 years old.” He was two years below grade level in reading and three years below in math. He could understand words in isolation, but he used few of them in his own speech and had trouble with phrases and sentences.

Carlos’s comprehension and memory were abnormal. When it came to understanding things in the moment, he could make a lot more sense of visual than of auditory cues—what he read as opposed to what he heard. But when it came to remembering what he had just learned, it was the opposite. So, he had problems either way: Things he read, he could understand but not remember. Things he heard, he could remember if he understood them, but he rarely did.

The psychologist recommended special education classes in reading and math.

Two years later, when Carlos was fourteen and in the eighth grade, the school district’s Special Education Committee put him through another round of medical and psychological evaluations. They concluded that he had “low average I.Q.,” “fine-motor difficulty,” possible “neurological difficulties” or “cerebral dysfunction,” and a “specific learning disability.” They recommended extending Carlos’s special education placement to history and science.

. . .

One thing Carlos was good at in junior high was football. His older brother played as well. But in the eighth grade, the school kicked Carlos off the team for failing his classes. No pass, no play. That was a big deal for Carlos and the other kids. He got tired of them laughing at him for being slow and quit school without finishing the eighth grade.

Margarita was fine with Carlos quitting junior high because he quickly got a job at the Whataburger. But looking back on it, Rose saw the setback as a turning point—when Carlos lost confidence and started heading in a different direction from her. For Rose, who eventually fought her way into the middle class—obtaining a good job in accounting even as her husband prospered in the real-estate and talent-recruiting businesses—the whole focus was on doing well in school and getting away from the life she saw around her.

“I didn’t want to live like that,” she told the investigators. “I didn’t want to have ten or fifteen kids, from all these different men and be on welfare and not be educated. So I was looking ahead.” But it was different for Carlos. Rose felt that he knew he couldn’t even keep up with the kids around him and decided he “didn’t care” what happened to him.

Rose believed that many things frightened Carlos, including the teasing he faced in school. But he was a good-looking kid, so he adapted by being “cocky,” a flashy dresser, and a “showoff.”

“If you would have known Carlos [as a teenager], he was very cocky, and always played this tough guy,” Rose said. But “in reality, he wasn’t anything like that. When you went one-to-one with him, he was the nicest person.”

. . .

Carlos’s clothes and his hair were a big part of his image (figure 5.2). “Carlos would never wear blue jeans,” Rose recalled. He “would never wear . . . flannel . . . shirts, sweats, flannel jackets, never.” He always wore pressed slacks and long-sleeved dress shirts. “He always looked nice, dressed nice all the time.” His pants were “polyester,” she said, “longer on the bottom of the legs, like bell-bottom pants.” “You would never see him but with black slacks,” she said. He liked black because it made him look thinner and platform shoes, to make him look taller.

FIGURE 5.2 Rose and Carlos DeLuna, late 1970s.

Describing Carlos’s shirts, Rose said it was “[a]lways . . . a dress shirt, always long-sleeved dress shirts, with the big [cuffs] around here [points to her wrists] and the long collars around here [points to her neck].” His shirt was “always . . . tucked” and unbuttoned “three or four buttons down.” “You never saw him in a T-shirt.” When he was younger he wore bright colors, but later he preferred white dress shirts—he had a closet full of them, a closet full of white shirts and black pants.

Carlos kept his wavy hair long and stylish, a comb at the ready. “Always kept” his hair “neat,” Rose recalled. “Always kept his appearance neat. Always shaved and cleaned.”

. . .

Twice after leaving school, Carlos had more psychological evaluations. Both findings were the same: low intelligence, higher “social” functioning, and pathetically obvious efforts to con the evaluator to hide what he could and couldn’t do.

Roland J. Brauer, Ph.D., ran a battery of tests on Carlos at a juvenile facility when Carlos was sixteen, noting a sharp discrepancy between Carlos’s “dull-normal” intellectual functioning and stronger “social awareness and social reasoning.” He reported that Carlos was “manipulative” during the exam—trying to “con” him about eye problems and headaches. Given Carlos’s “dull thinking,” however, the “manipulations” were “very transparent.”

If not for these “obvious” manipulations, Brauer wrote, Carlos “could be a pleasant boy to be around.”

When Carlos was arrested five years later for killing Wanda Lopez, a judge ordered two evaluations. Psychologist James Plaisted tested Carlos’s I.Q. as 72, borderline mentally retarded. At first, Carlos answered most of Plaisted’s questions by saying that he couldn’t remember anything, but “after rapport had been established and Mr. De Luna had become comfortable with answering questions,” he became more cooperative.

Plaisted concluded that Carlos was malingering and was smarter than tests showed, given his “obvious . . . effort to deceive me into thinking he was suffering from a psychotic process,” and because of differences between what Carlos claimed to comprehend on written tests and what he understood when the same words were spoken orally.

Plaisted knew a thing or two about deception himself. The year after examining Carlos, the psychologist was caught sexually molesting children in a church youth group that he ran. After more incidents, he ended up in prison on a forty-year sentence.

Psychiatrist Joel Kutnick performed the second evaluation of Carlos and afterward asked the prosecutor, Steven Schiwetz, to provide “background information in terms of how far this defendant got in school and whether there was a question of his being retarded,” as tests initially had suggested. Schiwetz said he would look but never came up with anything. Kutnick reported to the court that school records were “not obtainable” and agreed with Plaisted that DeLuna was malingering.

Twenty-one years later, investigators obtained Carlos’s school and juvenile evaluations within days of routine requests to the Corpus Christi School District and Juvenile Department. Both showed that his intelligence and learning capacity had been questioned since elementary school.

. . .

Shortly after quitting school, Carlos met a girl named Aida or Ida Sosa at the Casino Club. Rose described Aida as “a street girl,” who “lived in abandoned houses with men.” “That girl was trouble,” Rose said. In a letter to a news reporter in 1989, Carlos also associated Aida with trouble. “I think I was 15 years old,” he wrote, “when I first got in trouble with the Law. I was going out with this girl who was about two years older than me, and she had already been in trouble with the Law before.”

“I truly did love her, or . . . thought I did,” Carlos continued. “But I met her brother and his friends, and that’s where all the trouble started.”

Carlos asked Margarita if Aida could live with them. When Margarita refused, there was a fight. It ended, Rose recalled, when Carlos said, “[I]f you don’t let her come in, I’m going to move out,” and he did. Ever the follower, Carlos quickly adopted Aida’s lifestyle. The two lived in abandoned houses and began stealing from relatives and neighbors, sniffing paint, drinking, and getting in trouble with the police.

Rose recalled that they wouldn’t see Carlos for a while, but “[a]s soon as he ended up in jail, my mom would take him out of jail, and then he would do it all over again. It was a cycle, just a turning-wheel cycle.”

. . .

Carlos’s run-ins with the law began in early 1977, when he should have been in ninth grade. He was arrested once for truancy and twice for running away.

In September 1977, Carlos went to Dallas to join his brother Manuel, and his mother reported him missing. When he returned to Corpus a week later, the authorities put him in Juvenile Hall for counseling. Noting that the fifteen-year-old had been out of school for over a year and wouldn’t cooperate, the Juvenile Department concluded that “no help could be offered” and released him.

In 1978, the arrests got more serious. He was arrested in February of that year for attempted burglary and public drunkenness, but charges were dismissed for “insufficient evidence.” He was back in jail in March on charges of burglarizing a used-car lot across the street from the Casino Club, but the same prosecutor again dismissed the charges because he mistakenly charged DeLuna with a crime for which juvenile proceedings were not permitted.

On the last day of May, Corpus Christi police sergeant Enrique (Rick) Garcia stopped a 1969 Ford at the Casino Club that had been reported stolen from Garland, Texas. Carlos was driving the car, Aida was in the passenger seat, and Manuel was in the backseat. According to a police report, Carlos had run away to Garland and had stolen the car there. He had also reportedly broken into his mother’s house and stolen a television and other things, and not long before that he’d been caught 200 miles away in Abilene driving a car owned by the uncle of another boy in the vehicle.

No one was prosecuted for these crimes. The paperwork on the first car theft never reached Corpus Christi from Garland. And neither Carlos’s mother nor the uncle who owned the other car pressed charges. Instead, Margarita bailed Carlos out of jail.

Within weeks, police had Carlos and Aida red-handed on a new rap—sneaking an elderly woman’s purse out of her house after getting inside on Aida’s pretext of needing to make a phone call. Aida’s brother saw Carlos take a $10 bill and $30 in food stamps out of the woman’s wallet and called the police. Their report describes what happened next: “[W]e received a call to 504-1/2 Flood. . . . Upon arrival into the house we observed Ida standing by the bed looking down. There was also a very strong odor of spray paint. We asked Ida if Carlos was there and she said ‘Carlos who?’ We looked under the bed and found Carlos and ordered him out. . . . Carlos had silver paint on his hands and paint fumes on his breath.” Carlos had a spray can of Krylon silver paint and a beer can wet with the inhalant. Police reported that he and Aida “are currently co-habitating.” Carlos showed police where he and Aida had hidden the food stamps.

This was Carlos’s fifth referral to the local Juvenile Department in nine months, and the department finally took action. Its predisposition investigator Al Reyna reported that Carlos had “refused supervision” from Margarita for months, had moved into Aida’s apartment, and worked at odd jobs. As for Carlos’s arrest, “[o]ne moment he is admitting that he is at fault and the next moment he wants to sue everyone connected with his case.” Finding Carlos “completely out of control” and in need of a stable and structured environment and counseling, Reyna recommended commitment to a Texas Youth Council juvenile facility.

It was during this stay at the local Martineau Juvenile Shelter that Brauer evaluated Carlos, identifying his “dull-normal” intelligence and “transparent” manipulation. Brauer agreed that Carlos needed a structured environment where rules of behavior are reinforced: “His present living situation in which he is free to roam and do as he pleases is totally inadequate.”

While Carlos waited for the Juvenile Department to decide what to do with him, he and Aida were arrested again with a can of Krylon paint. Again, their hands and mouths were smeared with the stuff, but this time they were using it on the grounds of an elementary school. This was the earliest of Carlos’s arrests when police reported his possessions at the time of his arrest. They found a comb, tweezers, and a watch, but no weapon.

. . .

The Juvenile Department placed Carlos in the custody of the Texas Youth Council, or TYC, the state agency that handles long-term juvenile incarceration. What Carlos did in TYC custody and what its psychologist learned about him are unknown because the agency destroyed all 500 pages of his records in 2004, after twenty-five years had expired during which no one had asked for them.

Other law-enforcement records reveal, however, that Carlos was in and out of TYC programs and institutions during 1978 and 1979. Things hadn’t gone as Reyna and Brauer had hoped:

Between arrests, Carlos worked at a Whataburger and as a busboy at a sit-down restaurant.

With Carlos’s eighteenth birthday approaching, the TYC gave up on him in early 1980 and left him to the Corpus Christi police. By then, alcohol had replaced spray paint as his substance of choice to abuse. The Casino Club, to which Manuel, an underage regular, had introduced his younger brother a few years earlier, was Carlos’s favorite place to drink.

Other customers remembered Carlos from that time as “hyper. He talked fast and drank a lot.” A cop who moonlighted as a bouncer at the club said “regulars” there typically described DeLuna as “stupid or crazy.”

The next few months were a revolving door of trouble, jail stints, and more trouble:

| February 6, 1980 | Drunk and disorderly outside his mother’s home where he was loudly and profanely arguing with her and his stepfather (comb and billfold with no cash; no weapon) |

| February 7, 1980 | Minor consuming alcohol at the Casino Club after being turned away and sneaking back in (comb, billfold; no weapon) |

| March 5, 1980 | Trespassing at the Casino Club, which he insisted on entering when the owner as well as police told him he couldn’t; Sergeant Rick Garcia was the arresting officer (comb, billfold, cigarette lighter; no weapon) |

| March 28, 1980 | Public drunkenness and disturbance in the middle of the street outside Margarita’s home (comb, billfold; no weapon) |

| May 23, 1980 | Public intoxication after staggering up to a police officer who had arrested him a month earlier and daring him “to do it again” (comb, billfold, papers; no weapon) |

. . .

It was during this period when Rose, a year younger than Carlos and in high school, confronted Margarita about how strict and impatient she was with the other children and how tolerant she was of Carlos.

Resentful of the latitude that Margarita gave Carlos, Rose had some sympathy for how the Corpus police felt about her brother. Because Margarita was illiterate and spoke only Spanish, Rose often accompanied her to get Carlos out of jail.

“When he would go to jail, my mother was there to bail him out all the time,” Rose recalled. “And he would tell police officers, ‘you know I’m going to be . . . out of here in an hour. Watch my mom walk in, and she’s going to get me out.’ And that’s exactly what would happen.” Carlos “would just go out laughing, ‘I told you I’d be out.’” Rose believed that her brother “pissed of a lot of people in Corpus.”

“I believe strongly that a lot of those officers would say, ‘give him enough rope and one of these days he’s going to hang himself’. That’s what I believe.” Since those days, Rose has struggled with her love and resentment for her brother and her mom, and with her sympathy and hatred for the police and other authorities who played such a big role in bringing both of them down.

Rose despised Carlos’s constant stealing, lying, and huffing paint. But he was also a “kind heart,” always “helping you out if you needed help.” Carlos was the one who stuck up for her when Manuel blamed her for something he had instigated; the one who brought her hamburgers from work—“a big deal,” growing up in a poor family; the one who gave her lunch money because he knew how “embarrassing [it was], when you’re a teenager, and you have to go stand in line and get your free lunch ticket,” showing everyone you’re too poor to pay. Manuel worked, too, but he never did any of that.

Looking back on it, Rose took solace in one thing: for all his showing off as a teenager, Carlos died a humble man. Not, though, before the police gave Carlos his comeuppance.

On June 19, 1980, sheriff’s deputies arrested Carlos for attempted rape in Garland, where his older siblings lived. While on bail for that offense, he was arrested in nearby Dallas for driving a stolen car. He pleaded no contest to both charges.

In pleading to the first charge, Carlos admitted that he had followed the seventeen-year-old victim into a YWCA parking lot where he tore off her clothes and threatened to kill her if she didn’t stop resisting. He had no weapon.

Two witnesses approached and scared off DeLuna. The victim went home and got her brother, and they went looking for her attacker. They found Carlos, still at the YWCA, but he ran away, shedding his shirt and shoes.

The victim and her brother followed Carlos but lost sight of him at 4267 Munger. They went home, where they gave a description to the police. Officers went over to the Munger address to begin a search and, to their surprise, found Carlos still there, hiding “in bushes.” The victim and witnesses identified him at the scene.

Around the same time, Carlos also confessed to stealing a car from the driveway of a man named John Williams Jones. Dallas police officers caught DeLuna with the car two days later, when he ran a red light right in front of them.

Carlos was sentenced to two years minimum and three years maximum in prison for the two offenses. With credit for time spent in jail after his arrest and for good behavior while in prison, he was paroled sixteen months later, on February 23, 1982. He stayed out of trouble for nearly three months on parole, but not more. On May 14, Carlos attended a welcome-home party for Marcos Garcia, a friend from prison. Margarita and Blas left him off at the Garcia home, wearing black slacks and a blue, long-sleeve dress shirt.

Sometime after 11:00 P.M., Carlos and Marcos left the party together. An hour later, after midnight, witnesses saw Carlos return alone, and around 1:00 A.M. they saw him run out of the Garcia home with his blue shirt unbuttoned. In the meantime, Marcos’s fifty-three-year-old mother, Juanita Garcia, had awoken to find a man lying on top of her. The man put a pillow over her mouth and threatened her. She thought she recognized the voice as DeLuna’s and made out his silky blue shirt.

FIGURE 5.3 Booking photographs of Carlos DeLuna: (top left) November 30, 1979; (top right) December 23, 1979; (middle left) July 30, 1980; (middle right) 1982; (bottom left) January 21, 1983; (bottom right) July 26, 1983.

The man punched Garcia once in the ribs, breaking three of them; removed her clothes; unzipped his pants; and stroked and kissed her. Then he left suddenly. No weapon was used.

Police determined that there was no rape or attempted rape and charged Carlos with misdemeanor assault. They never prosecuted, however. Instead, prison officials revoked Carlos’s parole because he had left Corpus Christi without permission shortly after the incident at Marcos’s house. DeLuna was back in prison on June 22, 1982 (figure 5.3).

Prison officials paroled Carlos again on December 30, 1982, thirty-six days before Wanda Lopez was killed.

. . .

When Rose talked about the bridges that Carlos had burned by being cocky and “piss[ing] off a lot of the police officers in Corpus,” she might have been referring to Officer Thomas Mylett.

Mylett was the first Corpus Christi cop the police dispatcher had radioed to go to the Sigmor when Wanda screamed, but he never answered. Later, though, he joined the manhunt and helped Constable Ruben Rivera and Officer Mark Schauer pull Carlos out from under the pickup truck. It was Mylett who proposed bringing DeLuna “back” to the Sigmor for identification.

Mylett was also present when Schauer radioed in that he was driving Carlos the three blocks to the filling station and then, for unexplained reasons, took a quarter-hour to get there.

When they brought Carlos out from under the truck, Mylett recognized him as the twenty-year-old he’d arrested two weeks earlier at the Casino Club for drunk and disorderly conduct. The cop immediately broadcast the reason for the earlier arrest to anyone who was within radio-shot.

FIGURE 5.4 Television news shot of Detectives Olivia Escobedo and Paul Rivera escorting Carlos DeLuna through the “perp walk” outside the courthouse in Corpus Christi.

Mylett had been off duty, working security at the Casino Club, when Carlos, stinking drunk, stumbled up and asked if he “knew [Rick] Garcia, the police officer who was shot last year.” Carlos then told Mylett that he was glad Garcia had been shot and wished that he’d been killed. Garcia had himself arrested Carlos several times at the club.

Then, according to Mylett, “Subject asked if I wanted to fight about the conversation he just had with me. I . . . had the subject step outside the night club and arrested him for public intoxication and disorderly conduct.”

. . .

After pulling him out from under the pickup truck, Mylett and Schauer stood DeLuna up and checked his pockets, finding a billfold but no weapon. The police in Corpus Christi, Dallas, Garland, Abilene, and the other cities where he’d been arrested had never found a weapon on him. Detective Eddie Garza had never heard of DeLuna carrying a weapon. None of his siblings or friends had ever seen him with one. Rose was sure Carlos would never carry a gun or knife. He’d be too scared.

Still, as soon as Mylett recognized him and told the other officers who he was, they were sure that Carlos DeLuna had finally given them enough rope to hang him (figure 5.4).