The Case of Frenzy

Whatsoever therefore is consequent to a time of Warre, where every man is Enemy to every man; the same is consequent to the time, wherein men live without other security, than what their own strength, and their own invention shall furnish them withal. … and which is worst of all, continuall feare, and danger of violent death; And the life of man, solitary, poore, nasty, brutish, and short.

—Thomas Hobbes, Leviathan

The passion for philosophy, like that for religion, seems liable to this inconvenience, that, though it aims at the correction of our manners, and extirpation of our vices, it may only serve, by imprudent management, to foster a predominant inclination, and push the mind, with more determined resolution, towards that side, which already draws too much, by the bias and propensity of the natural temper.

—David Hume, An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding

Hell is a city much like London. The streets are paved with gold and all the maidens pretty. It’s the modern Babylon, it’s a kindly nurse and the great wen, that great cesspool. It’s the epitome of our times. It has everything that life can afford and when a man is tired of London he is tired of life. It depends on one’s point of view, none of the foregoing celebrated and hackneyed opinions being entirely true or entirely false.

—Arthur La Bern, Goodbye Piccadilly, Farewell Leicester Square1

HITCHCOCK’S FRENZY (1972) EXPLORES a recurrent theme in his films of the wrong man trapped and imperiled by the power of the State. Blaney (Jon Finch), more fittingly and ironically “Blamey” in Arthur La Bern’s novel, must negotiate an unjust world as both agent and acted upon, both free and restricted, and both at liberty and in fear. He wants his freedom and the exercise of his own desires, but at every turn he faces ethical obstacles, usually of his own making: accusations by his public house employer (Bernard Cribbins); disagreements with ex-wife Brenda (Barbara Leigh-Hunt); neglect by former friends, the Porters (Clive Swift and Billie Whitelaw); at times even suspicion from his lover, Babs Milligan (Anna Massey); and ultimately, when accused of serial murder, imprisonment by the State. In his more solemn alcohol-induced, self-pitying reflections, Blaney finds London society nasty and brutish, a world of ruthless competition and distrust. His self-preservation remains his foremost concern. At the same time, Blaney is his own worst enemy, acting out in anger, engaging in verbally violent confrontations with his ex-wife, and motivated almost exclusively by egotism. Clearly, passion controls him more than reason. In short, Blaney resides in a hostile Hobbesian social structure that he understands, like Hume, as unnatural and artificial, springing not from any sense of justice, but rather from self-interest. In Frenzy, Hitchcock places before the audience the philosophical dilemma of discerning moral justice in an apparently uncaring, unsympathetic, and overtly unjust world. Through the self-doubts of Chief Inspector Oxford (Alex McCowen), the film presents a philosophical inquiry on justice. The film’s resolution, Blaney’s retaliatory act of murder against the true serial killer, Robert Rusk (Barry Foster), further confounds the audience about the nature of human justice and morality. Of course, this confusion is precisely Hitchcock’s point, to offer a counter theory to Hobbes’s worldview and Hume’s skepticism.

Frenzy offers a complex narrative of brutality and skepticism. It operates in a clever manner by means of a chiasmus structure, a crossing over of filmic repetitions to forge a connection between the protagonist and his obverse reflection, the psychotic “necktie killer.” This chiasmus occurs in nearly every scene, whereby moral issues cross over to their opposite meanings, with the result being an uneasy moral experience for the audience. This obverse mirroring or criss-crossing of contradictory moral sentiments characterizes Hitchcock’s cinematic strategy, which relies on sequences of repetitions that challenge the notions of causality and moral certainty.

Structurally in Frenzy, Hitchcock plays with the philosophical concepts of skepticism, causation, and moral judgment. While Hitchcock, a devout Catholic, would never embrace a Hobbesian skepticism or Hume’s radical dismissal of cause-effect, he is willing to toy with these issues in order to manipulate his audience. The opening credits, with the magisterial helicopter fly-over shots up the middle of the Thames, serve as an homage to the great city, as well as an eye-of-God perspective on human civilization. The credit sequence is a long helicopter shot moving up the Thames to the County Hall across from the Houses of Parliament, where the film cuts to an outdoor political speech being delivered about proposed bills to cleanse the environment. This opening also undercuts any serious allegiance to government, particularly parliamentary rule, as evident by the foppish, ecologically faddish Minister of Health. His speech at County Hall is a perfect example of the irrationality of man trying to transform not only his own errors, but also Nature in the bargain. Cleaning up the Thames was part of the 1970s ethos of Earth Day, which took place one year before the production began on Frenzy. Although topical for the early 1970s political fetish for environmental reforms, this speech also makes for dark moral comedy by ironically commenting on the absurdity of man’s efforts to transform Nature.

The Minister quotes Wordsworth as he begins his address: “When I was a lad, a journey down the rivers of England was a truly blithe experience—bliss was it in that dawn to be alive, as Wordsworth has it” (Shaffer 1). Of course, this poetic citation is taken completely out of context from Book X of Wordsworth’s The Prelude, “Residence in France and French Revolution”:

O pleasant exercise of hope and joy!

For great were the auxiliars which then stood

Upon our side, we who were strong in love;

Bliss was it in that dawn to be alive,

But to be young was very heaven; O times,

In which the meager, stale forbidding ways

Of custom, law, and statute took at once

The attraction of a Country in Romance;

When Reason seem’d the most to assert her rights

When most intent on making of herself

A prime Enchanter to assist the work,

Which then was going forwards in her name.

(Wordsworth 196)

Here, Wordsworth is caught up in the youthful, hopeful zeal of a sense of a new world dictated by the Enlightenment of Pleasure and Reason, not staid politics and passé custom, but feeling, sensation, and experience. Still, Wordsworth writes of this bliss at the commencement of the transformation in France, before the unspeakable brutality of the September Massacres of 1792. The Minister’s misuse of Wordsworth ironically and comically sets the narrative pattern of Frenzy, whereby hope is diminished by reality, reason succumbs to overwrought passions, and morality loses out to depravity.

The camera shifts away from the Minister to members of the crowd, who have turned to look into the Thames below, as the Minister’s voice fades on a final word: “Let us rejoice that pollution will soon be banished from the waters of this river and that there will soon be no foreign bodies …” (2). The natural world of the Thames embankment is analogous to human nature in a very literal sense, since during these ecological platitudes a woman’s strangled naked body—a real foreign body—floats toward shore and disrupts the speech. This moment is the first moral chiasmus in Frenzy. Having a human body polluting the Thames is certainly the ironic touch of the master’s hand, a devious and derisive knock at the numerous riparian cleansings of the post-1968 era. Ameliorating social and environmental problems, however, come down to Hobbesian naked egotism. Upon seeing the body of a necktie-garroted woman on the edge of the Thames Embankment, the Minister drops all pretense of communal oneness and firm commitment to Earth-first rhetoric by instinctually resorting to bald self-interest, as he exclaims: “I say, that’s not my club tie, is it?” Such a misplaced causal connection would have amused both Thomas Hobbes and David Hume.

The film then cuts to Blaney tying his tie before he heads down to the bar to steal an early morning brandy at the pub where he works. An ex-military flier, Richard Blaney’s fame, glory, and sense of being are predicated on his past warlike state. In the civilian world, Blaney finds only obstacles, misfortune, and suspicion. He also finds it difficult to take any blame (hence, his ironic name in La Bern’s novel), even though he is confronted with blame by nearly everyone around him. After being sacked for supposedly pilfering brandy from the bar, Blaney storms out and then wanders through Covent Garden, where he meets up with Bob Rusk (Barry Foster), a fruit and vegetable dealer, who offers him the solace of a circling in the daily paper a sure-bet racing tip, a horse named “Coming Up,” and a box of fresh grapes, neither of which Blaney will enjoy. Blaney’s desire for immediate pleasure outweighs his contemplation of future benefit. Instead, he retreats to a nearby pub, orders a double brandy, and then scolds the bartender for not amply filling his glass. From these events, the audience observes a man clearly associated with antisocial behavior. The sequence of events establishes Blaney as a social outcast of sorts, and to the film’s audience, a person assumed to be guilty of crimes. Certainly, Blaney is a man quicker to ire and outbursts than to reason. All circumstantial evidence from the outset of Frenzy points to Blaney as a man very capable of violent behavior.

In the pub, the causal link between the sexual murder of women and Blaney garners more credibility with the introduction of a conversation between a solicitor and a physician who have entered for a pint and some lunch. As the audience soon discovers, the London world of Frenzy is a brutal one for women and for the thoroughly unsympathetic, drunken protagonist, Richard Blaney. The necktie murders have reawakened a sinister, skeptical side to London society. As the two men discuss and make bad jokes about the necktie killings, the camera shots include Blaney in the background and then at the bar, while this visual, causal association, a contingent relationship between the murderer and Blaney, establishes itself for the audience. The scene is typical of Hitchcock’s narrative pattern. At a moment when another director would insert cliché exposition, he often includes a scene of two seemingly inessential figures, usually male, who engage in what appears to be conversation unrelated to the main plot of the film, but which in fact resonates with the thematic structure and imagery at the heart of the matter. Such examples include the two police talking in Dr. Brulov’s (Michael Chekhov) parlor about caring for one’s mother and being ridiculed for it by his boss, Hennessey, thereby reiterating the Oedipal power struggle and problem of male impotency that are at the heart of Spellbound (1945) (Pomerance 80–82.) Here, the selection of solicitor and physician represents the dual forms of misjudgment in Frenzy, the legal and the psychiatric that will converge to convict an innocent man.

In this scene, the audience acquires some psychoanalytical assessments concerning the types of psychopath who commit rape-strangulation. In Shaffer’s script, the doctor explains that these killers are “social misfits,” who “appear as ordinary likeable adult fellows, but emotionally they remain as dangerous children,” and in a very Hobbesian phrase, “whose conduct may revert to a primitive, subhuman level at any moment” (18). For Hobbes, such a description could well apply to all mankind, since by nature, self-preservation and self-interest are the “free-standing, primitive moral fact” (Lloyd 154). So, the doctor’s argument is not limited to sexual sociopaths, especially when he admits that they are “being governed by the pleasure principle” (19). That pleasure principle, by the doctor’s own admission, extends to sexual jokes and to the atmosphere of London itself. Overhearing their grim conversation, Maisie, the bar mistress, asks (“hopefully”), “He rapes them first, doesn’t he?,” to which the doctor responds with an unsettling, sardonic grin: “I suppose it’s nice to know that every cloud has a silver lining” (18). London seems to thrive as a kind of hell filled with sexual psychopaths. A long history exists, from Jack the Ripper, who is mentioned in an exchange among crowd members observing the naked body in the Thames during the opening scene at the County Hall, to John Reginald Christie, who raped and strangled his numerous victims, not unlike the film’s psychopath’s modus operandi. “We haven’t had a good juicy series of sex murders since Christie,” the doctor mockingly regrets (20).

Of course, as Hobbes understood about human nature, if that pleasure principle is disrupted or threatened with pain, the reaction can prove to be quite dangerous. It should be noted the Blaney’s childish fits of pique overshadow the scene following his departure from the bar, when Bob Rusk, whose name means twice-baked bread used for teething toddlers, shouts down to him from his flat window. In a retrospectively odd moment, Rusk introduces Blaney to his dear Mum, from which attentive audience members should recall the doctor’s warning about psychopaths as “dangerous children.” Rusk inquires about “Coming Up,” his twenty-to-one winnings on the sure-bet, which Blaney has forgotten about, although he still has the newspaper. “Coming Up” is another ironic chiasmus in Frenzy, since Blaney’s world, particularly at this moment, is falling down. As Blaney walks away, his facial expression becomes “savage,” and he resorts once again to almost childish wrath, not reason:

He throws the box of grapes onto the pavement, and stamps on them violently so that they spurt messily all over the place. He storms off up the street. A few yards further on he angrily throws his newspaper into the gutter … (22).

Hitchcock, of course, remains typically very playful with causal connections and intentional misdirections of impressions in his films.

As with the pub scene, Hitchcock continually creates visual associations between Blaney and the psychopath. Hume assesses ideas as responses to impressions; in fact, for Hume, no idea can exist that did not derive from a sensory impression or experience: “A blind man can form no notion of colours; a deaf man of sounds. Restore either of them that sense, in which he is deficient; by opening this new inlet for his sensations, you also open an inlet for ideas; and he finds no difficulty in conceiving these objects” (Hume Enquiry, 98). Hume’s analogies are quite telling for film itself—the sight and sound experience producing the ideas, narrative, and thematic content of film. In Frenzy, sight and sound experiences form the basis for two essential diegetic details, both of which occur in types of flashbacks: one involving a montage of images when Rusk realizes that his monogrammed R tiepin is missing, and the other being the echoing sound of Blaney’s accusations about Rusk that Inspector Oxford recalls as he remains in the courtroom after the verdict has been rendered. In both instances, the audience has already had the experience of the visual montage associated with Rusk’s rape of Brenda Blaney and the shouts from Richard Blaney as he was led to the cells.

In order to understand the significant impact of these crucial moments in Frenzy from both an aesthetic and moral experience, it is necessary to work through Hume’s ideas on perception and causation in relation to film construction. Hume acquired some of his initial conceptualizations of causation from Malebranche. As P.J.E. Kail points out with comparisons between Malebranche’s De la recherche de la Vérité and Hume’s Treatise on Human Nature, in particular, Hume reworked Malebranche’s arguments on causation, occasionalism (all causes underwritten by God), and necessary connection in order to negate them. While Malebranche, not unlike Berkeley, locates all force, power, and connection in God’s will, Hume defies such a necessity:

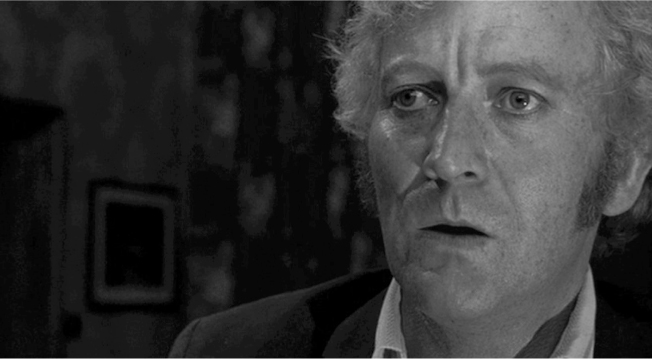

Figure 15.1. Frenzy—Rusk’s (Barry Foster) flashback post-murder.

Figure 15.2. Oxford’s (Alec McCowen) aural flashback of Blaney’s (Jon Finch) cries of innocence.

The idea of necessity—which does not represent anything “in the object”—is nothing other than the psychological effect of repeated experience. A veridical impression of necessary connection would make it genuinely inconceivable that an effect not follow its cause, but we have no such experience. Instead association fools us into thinking that we have such an experience, and hence idea, of necessary connection. (Kail 69)

For Hume, the necessity of connection occurs not from a first experience of an event, but rather from its repetition, and even then, one can only make an inference from a memory or an idea, which results from a vague recollection of a sense impression. Hume contends that one cannot conceive of red without ever having seen the color; or, one cannot reason that one object necessarily leads to another’s movement, as in a Newtonian motion, without having observed customarily that action. Hence, causal necessity is displaced or misplaced in a spatial region between cause and effect, not in the very objects themselves. For Hume, this amounts to an illusion of sorts, precisely because human beings wish to take from contiguous, associative, and conjoined objects a necessary cause and effect. Hitchcock understands that audiences possess this very same desire, and he exploits it.

Such precisely is the Kuleshov Effect by which audiences’ desire necessary connections, relationships, reactions, and cause-effect conjunctions between one image and another. Not that there exists any necessary or sufficient connection, but rather a desire for a connection. Moreover, Kuleshov’s Effect is based on the immediate, perceptual experience of the two images that produce the idea of a cause-effect connection when none whatsoever actually exists. As Kuleshov describes the discovery of this realization and its potential for cinema, he presents a case that very well could have come from Hitchcock:

We went to various motion picture theatres and began to observe which films produced the greatest effect on the viewer and how these were made—in other words, which films and which techniques of filmmaking held the viewer, and how we could make him sense what we had conceived, what we wished to show, and how we intended to do this. At that time, it was wholly unimportant to us whether this effect was beneficial or even harmful to the viewer. It was only important for us to locate the source of cinematographic impressibility, and we knew if we did discover this means, that we should be able to direct it to produce whatever effect was needed. (44–45)

Such is the very basis of film shot selection, editing, and theory of montage. While Hume understands the illusion of cause and effect, Hobbes’s philosophy depends on particular causality. Even if Hobbes views causation as multiple, complex, and often indecipherable, there must ultimately be a cause that effected an event, an action, and a result. Seeking that causal connection Hobbes sees as essential to the human predicament: “it is peculiar to the nature of Man, to be inquisitive into the Causes of the Events they see, some more, some lesse; but all men so much, as to be curious in the search of the causes of their own good and evill fortune” (Leviathan 12). Both Hobbes and Hume, then, concur that seeking out, inquiring into, and interpreting causes describe an all-too-human condition. In terms of his filmmaking, Hitchcock relies on this very human desire for making connections among a series of images, not only as a way to defer scenes of actual brutality, but also as a means for conditioning his audience to react to distinct images as though they were causally related.

For Hume, what we observe as cause-effect is contingent rather than necessary; that is, it is based on experiential perception, not a priori concepts, on a constant conjoining of perceptual experience, not from a transcendent idea of causation. Hume’s description of this process corresponds to the theory of film montage: “… we then begin to entertain the notion of cause and connexion. We then feel a new sentiment or impression, to wit, a customary connexion in the thought or imagination between one object and its usual attendant; and this sentiment is the original of that idea which we seek for. For as this idea arises from a number of similar instances, and not from any single instance …” (Enquiry 147). Sergei Eisenstein, according to David Bordwell, constructs his theory of polyphonic montage along similar lines as Hume’s idea of constant conjunction (384). Hitchcock understood the emotional power of creating a moral reaction through the use of Kuleshov’s and Eisenstein’s editing practices, precisely because by the time of Frenzy’s release, audiences had already experienced such editing effects in their film viewing that they were accustomed to drawing cause-effect inferences.

In the case of Frenzy, Hitchcock relies on the illusion of cause-effect in order to persuade the audience into accepting the imaginative world of his film. In terms of Hume’s concept of causation being an empirical experience, Hitchcock often structures his narrative according to these ideas from Hume. The accumulation of film experiences, the repetition of sense occurrences within the same film, produce the idea of cause and effect. Clearly, Hitchcock relies precisely on Hume’s concept of repetition of sensate events to produce the chills and frights in his audience, not by some outlandish surprise, but rather by providing the audience with a sensory experience that later can be called upon as the basis for a series of cause-effect shocks. In Psycho, for example, Detective Milton Arbogast (Martin Balsam) enters the Bates’s Gothic house, walks up the staircase, and in an overhead shot, the audience witnesses Mrs. Bates’s violent knife attack on the all-too-trusting private detective. His tumbling backward, almost suspended in mid-air, intensifies the audience’s reaction. Yet, the audience has already observed the incredible shower scene murder of Marion Crane (Janet Leigh) by Mrs. Bates. Arbogast’s death, then, is hardly a surprise; rather, it fulfills a causational expectation. The key to much of the Master of Suspense’s cinematic strategy lies in just this kind of imposed cause-effect that Hume demonstrated as acquired from repetition and custom. One can review any number of Hitchcock films and discover just this type of causational expectation, the formation of an idea of cause-effect, but really just an associative response to similar film moments.

In Frenzy, Hitchcock employs this causational association in several ways. The initial moment is the first necktie body in the Thames, followed by a quick cut to Richard Blaney tying his necktie in the mirror. This associative causation is not at all logical, since the body in the Thames is not the effect of Blaney’s actions. What Hitchcock works into the sequence is a sensory association of contiguous events, thereby making the audience falsely assume a cause-effect relationship. Perhaps in this connection an unconscious moral wariness, even condemnation occurs. By the time Blaney has intruded on his wife, Brenda, at her marital service office, raged against his misfortune so loudly as to alarm her secretary, Monica Barling (Jean Marsh), and later that evening, violently cut his hand at Brenda’s ladies club, the audience certainly views Blaney as being less than a morally upright character. At this point in Frenzy, Hitchcock has used the accumulation of perceptual experiences to fashion a plausible causal link between Blaney and the violent necktie murderer, as well as to impart a moral denigration of Blaney in the audience’s mind. Unlike other Hitchcock protagonists, Blaney’s conduct appears reprehensible, not mysterious like the Lodger (Ivor Novello) in The Lodger, not heroic like Hannay (Robert Donat) in The 39 Steps or Barry (Robert Cummings) in Saboteur, not sympathetic like Manny Balestrero (Henry Fonda) in The Wrong Man or Father Michael Logan (Montgomery Clift) in I Confess, and certainly not comic like Roger O. Thornhill (Cary Grant) in North by Northwest. The key to Frenzy’s successful moment of disclosure of the real psycho-sexual killer’s identity relies entirely on this series of misleading and occasionally false impressions about Blaney’s questionable ethics and seeming indifference to morality.

Nearly midway through Frenzy, Hitchcock, still employing the same repetitions of sensory experiences, shifts the audience’s moral offense from Blaney to Rusk. Hitchcock repeats the scene of violence in Brenda’s office, substituting Rusk, the real psychotic killer, for the outraged, abusive husband, Blaney. The audience has already experienced this setting as a site for potential violence—emotional, verbal, and psychological—toward Brenda, which produced a moral distaste for Blaney. The rape and murder scene stands out among Hitchcock’s films as his most controversial, but too often critics overlook its intent as his most effective scene for arousing moral outrage and disgust. Rusk enters Brenda’s office surreptitiously and walks around in a somewhat domineering, although uneasily overpolite manner as he discusses the agency’s refusal to find him a companion. Their exchange occurs through a series of reaction closeup shots. Although seated in a less powerful position, as she was during Blaney’s tirade, Brenda does not coax or reason with Rusk, but reacts with an assertive and accusatory tone: “How shall I put it? Certain peculiarities appeal to you. … And you need women who submit to them.” As Rusk tries to defend himself, that he likes flowers and the like, Brenda becomes more aggressive in her dismissal of his sexual desires, recasting her initial polite but firm stance into rightly moral intolerance by telling him to go elsewhere. At that point, Rusk leans over Brenda’s desk and reasserts his dominance by pitching his type of uncomfortable woo: “But this one to me is the best because I like you.” Then, in Rusk’s most sinister moment, especially after Brenda’s understated comments about his sadomasochistic perversity, he proclaims, “You’re my kind of woman.” At that moment, Brenda unwittingly makes a fatal error by voicing her complete moral contempt for Rusk: “Don’t be ridiculous.” As she attempts to make a call, in an effort to deflect Rusk’s attentions from her, he cuts off the connection. He recovers his composure by standing over her desk and commenting on her frugal lunch as he bites into the apple she has before her. Rusk invites her out to lunch. She hastily agrees, but tries to leave the room with the excuse to wash her hands. At this moment, the rape begins.

Rusk pushes her up against the wall, twists her arms behind her back, calls her “wicked,” and throws her down on the black leather couch. Brenda reacts by pushing her assailant off with her legs, but when she tries to flee, Rusk grabs her by the ankle and throws her down again on the office couch. The swiftness of this shot sequence and the focus on Brenda’s legs adds to the peril of her predicament, but Hitchcock’s focus here is more than mere sensationalism. He is establishing a visual association. When Rusk drags her by her feet back toward the couch, the camera does not reveal her face as she struggles toward the door. Instead, her legs stick out from her dress in a manner like Babs’s legs from the potato bag in the lorry. Brenda’s kicking Rusk will repeat itself later, in a darkly comic moment of repetition as retribution, with female legs extended from a potato bag smacking Rusk squarely in the face. Similarly, but more intensely graphic than the shower scene from Psycho, the rape and murder montage establishes yet another visual association that will produce the image of causation in this scene and later in Rusk’s flashback. In seventy-nine shots in just over three minutes (nearly a shot every two and a third seconds), Hitchcock rapidly employs a fragmented series of cuts between Rusk’s violence and Brenda’s emotional and terrified reactions, conveyed primarily through closeups that accelerate and intensify the horrifying rape and murder. The two longest sequences during this ninety-second scene of penetration focus on Brenda’s recitation of Psalm 91, as Stefan Sharff points out in his shot-by-shot analysis of Frenzy:

Presently starts another, most intense separation. Shot 83 is a tight close-up of Brenda’s head, looking to the side, she is reciting the ninety-first Psalm: “Thou shalt not be afraid for the terror of the night.” In the background we hear the “lovely, lovely” mutterings of the rapist (10 ½ sec.). Shot 84 is a close-up of Brenda’s bare breast (the same shot as we have seen before). She tries to cover it by pulling her slip. A small diamond studded medallion cross is seen on her chest (4 ½ sec.). Cut (shot 85) back to the close-up as in shot 83. She continues reciting. Rusk’s shadow moving back and forth is seen on her right shoulder (11 ½ sec.). (Sharff 191)

By focusing on Brenda for this longest shot sequence of the assault, Hitchcock indelibly imprints the horrific effect of the rape on the victim with a sustained editing sequence, oddly lacking in any music, that includes obvious images (the cross) and sounds (reciting the Psalm) to invoke moral reactions in the audience. Part of the controversy about this rape scene in particular has been its apparent explicitness, even though, like the shower scene in Psycho, not very much is revealed. Rather, Hitchcock relies on the audience to draw the causal, and quite disturbing, connections among the sequences of fragmented closeups.

The actual strangulation murder contains forty-four shots in one minute and forty seconds and produces a startlingly brutal rapid sequence of extreme closeups that shift between Brenda’s struggle for life and Rusk’s horrid panting in near orgasmic pleasure. Many of the shots last less than a second. Again, the fragmented montage of the murder effectively allows the audience to create a cause-effect relationship between separate shots of Rusk and Brenda’s face and throat. This technique is essential for the flashback that will occur later with Rusk. At that point in the film, Hitchcock has prepared the audience to imagine a causal sequence because of this previous, very disturbing perceptual experience. The unsettling shot of Brenda’s tongue sticking out at a grotesque angle is not simply Hitchcock’s invention, but part of Shaffer’s script: “THE CAMERA PANS DOWN the face to the tongue which is now thrust out repulsively” (49). This ghastly image repeats with the revealing of the final victim in Rusk’s bed, after Blaney unknowingly bludgeons the corpse and then pulls down the covers. Rusk staggers to Brenda’s desk, rifles through her purse for money, as he takes another bite from the apple, before picking his teeth with his monogrammed “R” tiepin and departing. The sequence with the fruit and tiepin will also be part of the flashback scene, only done in reverse order.

The brutal rape and strangulation of Brenda Blaney in her office establishes a cause-effect expectation when Rusk invites Babs Milligan up to his second-story flat, and uses the key phrase as they enter: “You’re my kind of woman.” In a one-minute, self-contained shot, the camera follows Rusk and Babs from the foyer entrance, up the first short flight of stairs, for a few steps on the small landing, up the next short flight to the second story, where Rusk moves ahead of Babs and opens the door; then, the camera reverses the movement down the upper flight, across the landing, down the first story flight, through the foyer, and out the door. Using the editing trick from Rope, the cut takes place as an anonymous man walks by carrying a bag of potatoes, with the cut occurring on the potatoes, ironically enough! Heralded by many critics as a masterful touch by Hitchcock, a tour de cinéma, this one-minute shot, however, is vital to the construction of Frenzy’s narrative and thematic content. In reversing the ascent to a descent, the camera indicates a moral corruption and violation about to occur. The one-minute shot also functions as a kind of memory of the previous rape of Brenda Blaney. The audience never sees Babs’s horrific rape and murder, but clearly understands that it will occur. Hitchcock brings the audience’s attention to exactly this experiential cause-effect association, since the audience is led visually from the effect back to the cause. The reversal of the camera movement suggests just that idea. According to Hume’s contentions about causation, the audience can make this association because it has already observed it before and it has all of the visual connections to formulate the result. In short, Hitchcock conditions his audience to make leaps from cause to effect, even though he need not reveal either in the process. Of course, moral disgust and fear occur as well.

The potato lorry scene constitutes one of Hitchcock’ greatest gallows humor film sequences. Again, this scene relies on a series of experiential cause-effect associations and contiguities, as well as a series of repetitions. After depositing the body within the potato sack into the back of the lorry, Rusk returns to his flat, tosses himself on the black leather couch, pours himself a glass of wine, and chews on a piece of bread. The perversion of the bread and wine symbolism repeats the corruption of the Adamic symbolism with the apple in Brenda’s office. As at the conclusion of Brenda’s rape, Rusk picks his teeth, but discovers to his utter dismay, that his monogrammed “R” tiepin is missing. He scours the room, including opening the bottom dresser drawer and rifling through Babs’s things, but to no avail. Hitchcock captures Rusk in a closeup of his face as he recalls Babs’s murder in a montage flashback. In twelve seconds of twelve rapid shots, Hitchcock employs a similar technique as when he conveyed Brenda’s murder. Because his audience has already experienced that fragmented montage of strangulation, Hitchcock can rely on the previous sensory experience to draw causal connections among the twelve extreme closeups that alternate between Rusk’s homicidal action and Babs’s defensive struggle. This time, however, the shots are of eyes, mouth, throat, hand, and finally, the tiepin as Babs’s hand grabs it. Realizing what has occurred, Rusk rushes back to the lorry.

The repetitions in this lorry truck sequence function with bizarre humor to accentuate Hitchcock’s twist on his own narrative convention, the near capture or discovery of an imperial hero, as occurs for Hannay in The 39 Steps, Barry in Saboteur, and of course, several close calls for Thornhill in North by Northwest. There are several dual incidents that bring out comic suspense to the scene: two times the lorry’s rear gate is opened, the first when Rusk enters and the second when he comically tumbles out at the pull-out; twice the lorry’s rear gate is closed, once when Rusk enters to retrieve his tiepin and later, when the trucker has to insure that no more of the load will spill onto the road; twice Babs’s leg, in a grotesque slapstick, kicks Rusk in the face; twice he fears being caught as he sneezes from the potato dust; twice Babs’s body becomes exposed to potential witnesses, the first when Rusk must cover her foot and his head from the trucker’s view and the second when her leg sticks out from the back of the lorry, which arouses the suspicion of the police on patrol; and twice the lorry’s load falls onto the road, first the potatoes, and finally, when Babs’s naked body, with her upper torso and head still confined to the potato sack, topples out and is nearly run over by the pursuing police car. When the police uncover her, Babs’s eyes are wide open and her mouth is open, almost expressing a hideous risus sardonicus, which further adds to Hitchcock’s mixture of the frenzied and the humorous. Whenever a moment of dark humor arises, Hitchcock undercuts it almost immediately with a monstrous incident, such as the sound of Babs’s fingers breaking as Rusk retrieves his monogrammed “R” tiepin. With these repetitions, Hitchcock forces his audience to anticipate the second, repeated occurrences by means of constructing a causal link. As with his previous scenes of rape, murder, and depravity, visual experiences lead to expected cinematic effects. Moreover, by placing the audience in a very uncomfortable position for the audience, between laughter and repulsion, Hitchcock forces them to question their moral assumptions.

This uneasy shifting of moral responses with humor typifies most Hitchcock films, but it also lays bare the alternating circumstances that produce the binary concepts of good and evil. In the sixth chapter of Leviathan, Hobbes catalogues pairs of foundational passions that accord with Hitchcock’s emotional divisions in his films: desire and aversion, love and hate, joy and grief. In Hobbes’s anatomical analysis of mankind, appetites and aversion do not remain constant, but as the body changes over time, so do they. His observation of the human body being “in continual mutation” leads Hobbes to dismiss the binary and rigid moral categories of good and evil:

But whatsoever is the object of any mans Appetite or Desire; that is it, which he for his part calleth Good: And the object of his Hate, and Aversion, Evill; and of his Contempt, Vile, and Inconsiderable. For these words of Good, Evill, and Contemptible, are ever used with relation to the person that useth them: There being nothing simply and absolutely so; nor any common Rule of Good and Evill, to be taken from the nature of the objects themselves. (Leviathan 120)

This shifting dialectic of morality occurs because that is what occurs in nature—motion and change. Man, for Hobbes, is a natural being, and as such, responds to the world and society with a need for self-satisfaction and preservation. Hobbes thus rejects metaphysics in favor of a natural philosophy, as Gary B. Herbert contends: “The natural axiom of human behaviour is nothing more than that man, by natural necessity, desires his own good and shuns whatever is destructive of his well-being” (114). Rusk fulfills the Hobbesian view of passion, since he readily acts on appetite, an immediate satisfaction, and desire, an extended duration for satiability. Hitchcock portrays Rusk in this manner by associating him with the consumption of natural foods—raw fruits and vegetables. Symbolically, grapes, apples, and potatoes represent Rusk’s desires, however morbid and twisted, as Dionysian frenzy, sexual temptation, and earthiness and filth. Food for Inspector Oxford, on the other hand, is always a form of aversion. As his wife (Vivien Merchant) brings him new courses, while he discusses the open case of the necktie murders, Oxford observes the soupe de poisson with apprehension, shudders at the discovery of a fish head, then eye, then skeleton in his bowl, and reacts visibly shaken when his wife informs him of the contents: “They’re Smelts, Ling, Conger eel, John Dory, Pilchards, and Frogfish” (Shaffer 89). Oxford’s reaction to the meal simulates the audience’s reactions to the crimes—disgust, rejection, and aversion.

Like Hobbes in some respects, Hume has a naturalist or realist view of morality, especially the distinctions between good and evil, which arise from the senses and experience: “To approve of one character, to condemn another, are only so many different perceptions” (Treatise 67). In Book III: Of Morals in A Treatise of Human Nature, Hume maintains that “moral good or evil” arise from “particular pains or pleasures,” which relate to “distinguishing impressions” of the senses and experience:

To have the sense of virtue, is nothing but to feel a satisfaction of a particular kind from the contemplation of a character. The very feeling constitutes our praise or admiration. We go no further; nor do we enquire into the cause of the satisfaction. We do not infer a character to be virtuous, because it pleases: But in feeling that it pleases after such a particular manner, we in effect feel that it is virtuous. The case is the same as in our judgments concerning all kinds of beauty, and tastes, and sensations. Our approbation is imply’d in the immediate pleasure they convey to us. (78)

Thus, Hume dismisses arguments purporting that Reason, which he believed was a slave to the passions, controls man’s means or ends, thereby removing any theological grounding for morality. In the end, morality of good and evil is as artificial—that is, arising from custom, convention, and tradition—for Hume as it is for Hobbes. To be fair to both philosophers, their skepticism about the cause of morality—metaphysical, theological, natural, or teleological—does not mean that they promote immorality, or even amorality. For Hobbes, morality transforms into a necessary and willing submission to the sovereign or the State. For Hume, morality arises from sympathy, literally a similar feeling, that allows individuals to identify utilitarian ends according to the pleasure or pain they produce and to evaluate them by sentiment, that is, by the passion, not the process of reasoning, experienced.2 In terms of Frenzy, Hume’s sympathy and sentiment find their way into the disquieting doubts of Inspector Oxford. Contrary to Hobbes’s reliance on the sovereign authority (read the court and the police) to rid society of discord, the State finds its antithesis in the Blaney case, whereby all judicial procedures were based in error, and the result is detrimental to the commonwealth.

Social justice imposed against the supposed serial killer is reversed by means of Inspector Oxford’s skepticism, which is the narrative shift that parallels Blaney’s escape and his subsequent murderous intent at the film’s conclusion. In fact, it is the film’s conclusion that requires the most careful examination in terms of assessing Hitchcockian morality. Hitchcock leads the audience to question Blaney’s guilt in a moment of perceptual repetition, this time with sound. Court No. 1 of the Old Bailey, where Blaney’s murder trial takes place, is given extensive description in La Bern’s novel, including the judge’s detailed instructions to the jury. Hitchcock, though, wishes to coax his audience into an aural framework that will relate to the visual repetitions of the two rapes. A guard posted outside the inner double doors of the courtroom opens them to admit a barrister, and in that brief moment, the audience can discern the judge’s voice asking the jury for its verdict. The door then closes and silences the response. The audience waits in anticipation, listening as carefully for any clue, which occurs with the pronouncement of a sentence for which there will be no hope of release. Then, the door closes again. Blaney’s shouts awaken the guard’s curiosity, and he opens the door. Blaney screams several times, “Rusk did it!” as guards drag him from the box down the stairs to the cells, in a moment not unlike the reversal staircase scene of Babs’s rape and murder. Blaney has been reduced to a Hobbesian man, for whom justice is utterly meaningless:

To this warre of every man against every man, this also is consequent; that nothing can be Unjust. The notions of Right and Wrong, Justice and Injustice have there no place. Where there is no common Power, there is no Law; where no Law, no Injustice.

Force and Fraud, are in warre the two Cardinall vertues. (Leviathan 188)

Blaney is not alone in questioning Justice. In an overhead shot, the camera observes Blaney thrown into his cell and then cuts to an overhead shot of Inspector Oxford alone in the empty courtroom. In a medium closeup of Oxford, Blaney’s voice echoes his accusations against Rusk and his homicidal threats. This aural flashback functions in a similar mode to the visual flashbacks associated with the rapes and murders of Brenda and Babs. Here, instead of an inverted, perverse world dominating, Hitchcock offers a hope for a poetic justice of sorts.

Hume’s causation critique and disparity between passion and reason in human understanding extend to dinner conversations between Inspector Oxford and his wife. It should be noted that none of these scenes with the Oxfords at home can be found in La Bern’s novel; they are Hitchcock’s comic relief, to displace the misogyny and degradation of the rapes and murders. Oxford’s predicament, like everyone’s for Hume, rests on an inability to make absolute causal connections, even though he feels that Blaney must assuredly be innocent. He explains this dilemma to his wife, while she prepares pied de porc à la mode de Caen and asserts that intuition not science would have solved the case from the outset: “A woman’s intuition is worth far more than all those laboratories” (134). When Oxford confesses the lack of proof pointing to Rusk’s guilt, in an exchange that Hume would applaud, the nature of human understanding becomes all too apparent:

MRS OXFORD: Well, there you are. You told me the man’s a sexual pervert. That’s why he kept the clothes he put in poor Mr. Blaney’s case.

OXFORD (V.O): We’ve no proof of that.

MRS OXFORD: It stands to reason.

OXFORD: Don’t you mean intuition? (135)

In this comic domestic scene, Shaffer sums up Hume’s attacks on a priori intuition and on the assertion by reason alone for causation. Both lead to inconclusive assumptions, no matter how earnest they may be for seeking out justice. That piece of evidence that Rusk sought from Babs’s corpse is never discovered by the police in the film. Since Babs’s body was already “deep in rigor mortis,” Rusk had “to break the fingers of the right hand,” which Hitchcock has Mrs. Oxford unconsciously repeat by snapping a bread stick in two, and then in two again (137). The audience already anticipates this comic repetition at the moment that Mrs. Oxford picks up the bread stick. Because the audience has endured the initial breaking of Babs’s cold, dead fingers, this moment repeats, but relieves, that grotesquerie. Moreover, the Oxfords’ domestic comedy reasserts normal, heterosexual relationships in a film that exposes the most deviant displays of sexual power. This scene also befits the comedy of errors that British justice has displayed and that made Blaney experience homicidal rage.

In some respects, Blaney has gone a bit mad and experiences a kind of frenzy in the courtroom. Certainly, Hobbes conceived of frenzy as “passions run amok, overvehement by our ordinary standards, and unguided by reason” (Lloyd 187). For Hobbes, madness derives from “conceit or of a sense of inferiority,” which, in general, is contrary to “man’s wish to take pleasure in himself by considering his own superiority” (Strauss 12). Hume’s conception of madness, in part, derives from an inability to distinguish between impressions and ideas, because, like sleep or fever, “in spite of their strong force and vivacity, is that the external objects which the ideas represent are not present” (Wright 64). Certainly, to observers in the courtroom, Blaney’s searching for the absent Rusk and threatening him with his own brand of justice must appear as a form of madness. Now, Blaney exists in a hinterland between all-out war against society’s irrational and unjust conventions of jurisprudence and his own irrational sense to make present what is so wholly absent—justice in an unjust world. As he did in the film’s opening sequences, Blaney reacts from passion, not from reason.

In terms of Hobbes’s concept of obligation, especially to the State, Blaney is a counterexample in paradox: he wants to oblige authorities and, at the same time, realizes he cannot do so without risking his own life. Hobbesian self-preservation applies here, but not in order to sustain the State, but rather to show the façade which is the State, particularly the judicial system. Of course, Blaney is a Hobbesian man, who seeks no obligation except that which conforms to his concept of freedom, which is a “radically voluntarist doctrine” that is central to Hobbes’s “commitment to individuality and individual self-making” (Flatham 71, 72). The problem for Blaney, in both a legal and moral sense, remains his ignorance of the predictable sociopolitical structure of a Hobbesian exchange of “natural liberty for a state of obligation” (Skinner 104). Hobbes himself makes clear in Leviathan that the de facto obligation to obey ceases when one is no longer protected by the State (Chapter 21). As Jeffrey R. Collins reiterates throughout The Allegiance of Thomas Hobbes, in the world of seventeenth-century revolutionary and reactionary politics, Hobbes’s ideas on obligation could only be characterized as “an utterly static feature of his political theory, appearing without significant change in all of his writings” (Collins 120). In a Hobbesian world, which is often the world that Hitchcock critiques, even the natural liberty and innocence of the condemned man hardly affect the social construction of society, as Susanne Sreedhar contends:

These individual acts of disobedience and resistance are unthreatening to the sovereign power, according to Hobbes. Indeed, one of the ways he argues for the true liberties of subjects is by appeal to the negligible consequences of their exercise. The condemned man is still put to death. His resistance, although justified, is political ineffectual, especially since, as Hobbes insists, the sovereign’s right to punish the resistance is in no way jeopardized by the subject’s right to resist. (160–61)

Blaney’s resistance to the judge, as expressed by his repeated claims of his own innocence and his willingness to murder Rusk, have little effect on the imposing and the carrying-out of his sentence.

In fact, Blaney’s escape from the prison hospital is inconsequential to the grand scheme of res judicata. Hobbesian reciprocity, which is the central axiom of moral reasoning, in the covenant between individuals and the State, hardly extends to Blaney’s predicament. He served the nation as a military figure, but found nothing for him upon returning to society; he has a moral compass, but socioeconomic pressures test the boundaries of his commitment to conventional morality. Blaney certainly consents to his obligations to the State, although being accused of gruesome, sexual murders places him within a moral and social dilemma, even though he is not guilty of any of these horrific crimes. This dilemma is precisely Hitchcock’s point: How can one obey the Law when the Law fails to seek justice? Or, put another way, how can one obey the Law when it appears to violate the very concept of Law itself? In order for Blaney to survive, he must counter all civil and social customs in favor of the instinct of self-preservation.

The conclusion leaves more questions than it answers. Blaney fakes a suicidal tumble down the prison stairs, lands in the prison wing of a hospital, escapes with the help of his fellow inmates and a swiped physician’s lab coat, hotwires and steals a car, and arrives at Rusk’s flat prepared to kill him. The causal links that could have produced such an elaborate scheme and execution of that plan remain missing from the narrative. In the ironic world of Hitchcock, Blaney uses his newly acquired tire iron to beat to death an already deceased woman, not his intended target—Rusk. Inspector Oxford arrives to find Blaney standing over the naked, beaten, and strangled woman. The reaction that spreads across Oxford’s face perfectly illustrates false reasoning from effect to cause, for he appears to indict Blaney once again for crimes he did not commit while simultaneously realizing the error of his emotional judgment for supporting Blaney’s innocence. Just at the moment of arrest, the thumping of a steamer trunk can be heard coming up the stairs. A panting Rusk enters, turns, and realizes to his shock that Blaney and Oxford have caught him red-handed. Oxford’s words conclude the film: “Mr. Rusk, you’re not wearing your tie.” Hitchcock, however, leaves his audience with an ambiguous moral conclusion. Is the world relentlessly bent on aggression, meanness, deception, and self-interest? Is there little chance at proving guilt or innocence, right or wrong, good or evil in the world, without it having an adverse effect? In the end, Hitchcock leaves moral judgments to the audience, which may prove to be as unsettling in retrospect as the feelings induced by the rapes and murders.

1. Thomas Hobbes, Leviathan, ed. C.B. Macpherson (Harmondsworth, England: Penguin Books, 1974): 180; David Hume, An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding, ed. Tom L. Beauchamp (Oxford: Oxford UP, 1999): 119; Arthur La Bern, Frenzy (New York: Paperback Library, 1971): 35; this novel was originally published in 1966 under the title Goodbye Piccadilly, Farewell Leicester Square. Hereafter these works will be cited in the text.

2. For a discussion of Hume’s moral psychology, see Russell Hardin, David Hume: Moral & Political Theorist (Oxford: Oxford UP, 2007), in particular his sections on “The Limited Role of Reason,” “Sympathy and Moral Sentiments,” and “Natural and Artificial Virtues.”

Bordwell, David. “Sergei Eisenstein.” The Routledge Companion to Philosophy and Film. Eds. Paisely Livingstone and Carl Plantinga. Oxford: Routledge, 2009.

Collins, Jeffrey R. The Allegiance of Thomas Hobbes. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2005.

Flatham, Richard E. Thomas Hobbes: Skepticism, Individuality, and Chastened Politics. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2002.

Hardin, Russell. David Hume: Moral & Political Theorist. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2007.

Herbert, Gary B. Thomas Hobbes: The Unity of Scientific & Moral Wisdom. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 1989.

Hobbes, Thomas. Leviathan. Ed. C.B. Macpherson. Harmondsworth, England: Penguin Books, 1974.

Hume, David. An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding. Ed. Tom L. Beauchamp. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1999.

———. A Treatise on Human Nature in Moral Philosophy. Ed. Geoffrey Sayre-McCord. Indianapolis, IN: Hackett Publishing, 2006.

Kail, P.J.E. “On Hume’s Appropriation of Malebranche: Causation and Self.” European Journal of Philosophy 16.1 (2007): 55–80.

Kuleshov, Lev. “Art of the Cinema.” Kuleshov on Film: Writings of Lev Kuleshov. Trans. Ronald Levaco. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1974.

La Bern, Arthur. Frenzy. New York: Paperback Library, 1971. Originally published as Goodbye Piccadilly, Farewell Leicester Square, 1966.

Lloyd, S.A. Morality in the Philosophy of Thomas Hobbes: Cases in the Law of Nature. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2009.

Pomerance, Murray. An Eye for Hitchcock. New Brunswick: Rutgers UP, 2004.

Skinner, Quentin. Hobbes and Republican Liberty. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2008.

Shaffer, Anthony. Frenzy, July 21, 1971. Production No. 05110.

Sharff, Stefan. Alfred Hitchcock’s High Vernacular: Theory and Practice. New York: Columbia UP, 1991.

Strauss, Leo. The Political Philosophy of Hobbes: Its Basis and Its Genesis. Trans. Elsa M. Sinclair. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996.

Sreedhar, Susanne. Hobbes on Resistance: Defying the Leviathan. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2010.

Wordsworth, William. The Prelude or Growth of a Poet’s Mind (Text of 1805). Ed. Ernest de Selincourt. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1933.

Wright, John P. Hume’s ‘A Treatise of Human Nature’: An Introduction. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2009.