9

Integration

In April 1947 Jackie Robinson played his first game for the Brooklyn Dodgers, bringing an end to a sixty-year ban on black players in the Major Leagues. The story of Robinson and the brave men who followed his lead and helped change the game has been told often and well over the succeeding years in articles, books, and movies. Robinson’s bravery and outstanding play combined to right baseball’s great wrong and led the way for many other players who followed.

Although baseball’s belated foray into social justice is worth all the attention it has received, the issue that concerns us here is that the integration of the game had an extraordinary impact on how a team could be built. Jackie Robinson improved baseball ethically and morally, but he also made it better because he was a great player, and his playing time came at the expense of someone who was a lesser player. Robinson opened the doors for a vast new source of baseball talent, and that talent could not help but dramatically improve the game.

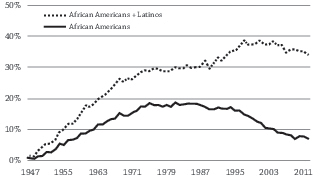

Robinson paved the way for all dark-skinned players, whether they were African American or Latino. Although light-skinned Latinos occasionally played in the Majors before 1947 (making up less than 1 percent of all players), the integration of the game led to the gradual acceptance of all Latinos, not just those who were adequately light-skinned. Chart 2 illustrates the speed with which the game integrated.1

In 1950 only five teams had integrated. As more and more teams, however, became willing to incorporate dark-skinned players and began scouting the new talent pool, the ratio of nonwhite players increased until it reached 20 percent in the early 1960s and 30 percent by the mid-1970s. Although the twenty-first century has seen a decline in African American players, the large number of Afro-Latinos has kept the overall percentage well over 30 percent since 1990.

Moreover, the mere number of players understates their value. From 1947 to 2013 African American players have won 47 MVP awards and Latinos another 21, totaling more than one-half of the 134 awards given in the period, much more than their proportional representation suggests they should have won. Chart 3 illuminates, alternatively, the percentage of total wins above replacement contributed by this group of players. Despite their still modest numbers, nonwhite players were contributing one-third of the WAR in baseball by the early 1960s and have been well above that ever since.

Chart 2. Percentage change in African Americans and Latinos

Source: Database owned and maintained by the authors.

Although all sorts of inferences can be drawn from the data, what we will focus on here is the impact of this newly accessible talent pool on a Major League organization trying to build its team. When baseball integrated in 1947, most teams were likely oblivious to how much talent had just become available. There were not just a handful of players who could play in the Majors, but dozens of them, many of them among the greatest players ever to play the game: Willie Mays, Henry Aaron, Ernie Banks, Roberto Clemente, and Frank Robinson were discovered and signed within a five-year period.

In order to take advantage of this extraordinary point in time, a baseball team needed both moral courage (although this arguably became less important by the mid-1950s when blacks were excelling in the game) and the willingness to expend the additional time and money to find and scout these players. If a team employed a dozen scouts spread over a still largely segregated country, chances are they would not have seen many dark-skinned players unless they were instructed to do so, to go see different games in different towns and cities. In a similar vein, as the previous figures illustrate, the Major Leagues did not really efficiently mine the talent in Latin America until the 1990s.

Chart 3. African American and Latino player value

Source: Database owned and maintained by the authors.

Jules Tygiel, the preeminent scholar of baseball’s integration period, pointed out that it was not enough that a team express a willingness to integrate, or even to have a legitimate willingness to do so. A team had to redirect its scouts or hire new ones, including Latino scouts for Mexico and the Caribbean.2 The Boston Red Sox often claimed to be looking for black players in the 1950s, and they made a few high-profile attempts to acquire established blacks, but they were the last team to actually field a black Major League player, in 1959. They had the money—their owner, Tom Yawkey, might have been the richest man in the game—but when faced with one of history’s great talent windfalls, they sat on their hands.

The pace of integration moved slowly in the early years; through 1953 only nine of the sixteen teams had fielded a black player. But although there were only twenty-four blacks in the game, these included several future Hall of Famers: the Dodgers’ Jackie Robinson and Roy Campanella, the Giants’ Willie Mays and Monte Irvin, the Indians’ Larry Doby, and the Cubs’ Ernie Banks. Over the next few years the pace quickened, especially in the National League, where there were thirty-six blacks in 1956 and sixty-six in 1960.

Importantly, these players changed the balance of power in baseball, especially in the NL. The Dodgers and Giants, both heavily integrated, won all six NL pennants between 1951 and 1956. The Milwaukee Braves, fortified by Henry Aaron in 1954 and reinforced by other black players such as Billy Bruton, Wes Covington, and Juan Pizarro, won pennants in 1957 and 1958. Competing with these teams without black players, at least in the National League, proved to be nearly impossible.

The American League trends were much different. The Yankees had so much talent already, and were competing with so many dysfunctional AL franchises, that they were able to ride three great white stars—Mickey Mantle, Whitey Ford, and Yogi Berra—to eight pennants in the decade without aggressively pursuing the new market. Elston Howard was their first black player, in 1955, and he played a big role in several pennants. The Yankees’ toughest regular-season competition came from the Cleveland Indians and the Chicago White Sox, the two most integrated teams in the AL.

As examined in the next chapter, the St. Louis Cardinals experienced the other side of this revolution. Initially, their response to integration was embarrassing. Stories that players on the team tried to strike rather than play against Robinson have persisted to this day, though all the principals have denied them. More important, the organization did not employ any blacks for more than seven years after Robinson’s 1945 signing and did not field a black on the big-league club until 1954.

Fred Saigh, the team’s owner until 1953, told interviewer Bill Marshall years later, “I think we were thought of as a team from the South.” He claimed the club sold more tickets “largely because of the mail we’d get—‘Well, we’re glad you’re not scumming.’” Saigh also claimed a difference between the writers that covered the Cardinals and the eastern writers, who were “Jewish boys” and “minority minded.”3 The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People threatened to boycott Cardinal games in 1952 if they did not sign a black player. Saigh responded that the team was trying to integrate and that the team was actively scouting the Negro Leagues for players.4 Nonetheless, the club had signed no blacks before Saigh sold the team.

Prior to Jackie Robinson’s debut, the Cardinals had been the dominant team in the National League, winning nine pennants and six World Series in twenty-one years. The all-white Cardinals gave the Dodgers a tough fight in 1949, losing by a single game, but the problem began to catch up with them—they did not receive a notable contribution from a black player until 1959. Not coincidentally, they spent a decade out of contention, watching their well-integrated competition represent the NL in the World Series every year.

By the 1960s the advantages gained by the early integrators had dissipated, and the ever-increasing numbers of black stars were being distributed more equally throughout the Major Leagues. But the lesson of this period—that teams can gain an advantage from a newly discovered (or newly permitted) talent source—would play out again (to a lesser degree) in Latin America in the 1980s and in Asia around 2000. In 2013, after an increasing number of their players had defected and found riches in U.S. baseball, Cuba announced that it would now allow its baseball players to sign contracts with U.S. teams.5 How this will affect the vast talent on that Caribbean island is not known at the time of this writing, nor is how the various Major League teams will deal with this new reality.