CHAPTER 5

Befriending Our Parts: Sowing the Seeds of Compassion

“Mindfulness is an act of hospitality. A way of learning to treat ourselves with kindness and care that slowly begins to percolate into the deepest recesses of our being while gradually offering us the possibility of relating to others in the same manner. … [The] process simply asks us to entertain the possibility of offering hospitality to ourselves no matter what we are feeling or thinking. This has nothing to do with denial or self-justification for unkind or undesirable actions, but it has everything to do with self-compassion when facing the rough, shadowy, difficult, or uncooked aspects of our lives.”

(Santorelli, 2014, p. 1)

Reclaiming Our Lost Selves

While yearning to “like” ourselves, the disowning of traumatic experiences or the vulnerable, ashamed, angry, or depressed parts holding implicit memories of those experiences results in a profound alienation from self: “I don’t know myself, but one thing is clear: I don’t like myself.” The ability to be compassionate or comforting or curious with others, which comes so easily to many trauma survivors, is not matched by the ability to offer themselves the same kindness. What it took to survive has created a bind. It was adaptive “then” to avoid comfort or self-compassion, to shame and self-judge before attachment figures could find them lacking, but now it has come to feel believable that others deserve or belong or are worth more—while, at the same time, it also feels that these “others” are not to be trusted; they are dangerous or uncaring.

It is a well-accepted premise that, to feel safe in any relationship, human beings need compassion both for themselves and for the other. Internal attachment bonds or “earned secure attachment” (Siegel, 1999) give us emotional resilience. The internalization of secure attachment allows individuals to tolerate hurt, loneliness, anxiety, disappointment, frustration, and rejection—all the risks inherent in any close relationship. But in order to unconditionally accept ourselves and “earn” that resilience, we need to develop a relationship to all of us: to our wounded and needy parts, to the parts hostile to vulnerability, to the parts that survived by distancing and denial—to the parts we love, the parts we hate, and even the parts that intimidate us.

Embedded in most methods of psychotherapy is the belief that “healing” is the outcome of a relational process: that if we are wounded in an unsafe relationship, the wounds must heal in a context of relational safety. But what if the quality of our internal attachment bonds, rather than our interpersonal attachments, is a more powerful determinant of our ability to feel safe? What if attachment to ourselves is a bigger contributor to the sense of well-being than the attachment we feel to and from others? What if being witnessed as we recall painful events does not heal the injuries caused by those experiences? And what if compassion for the child who lived through these events is more important than knowing the details of what happened? If that is so, and I believe it is, then trauma treatment must focus less on painful and traumatic events and more on cultivating compassion for our disowned selves and their painful experiences. When all parts of us feel internally connected and held lovingly inside, each can experience feeling safe, welcome, and worthy, often for the first time. The first step is to become curious about this “other” inside whom we do not really know.

The Role of Mindfulness: How We Can “Befriend” Ourselves

To observe and identify the signs indicating parts activity requires a witnessing mind capable of focused concentration or “directed mindfulness” (Ogden & Fisher, 2015). Mindfulness has an important role to play in the treatment of trauma because of its effects on the brain and body. Mindfulness practices counteract trauma-related cortical inhibition, regulate autonomic activation, and allow us to have a relationship of interest and curiosity toward our feelings, thoughts, and body responses—or parts. In brain scan studies, mindful concentration has been associated with increased activity in the medial prefrontal cortex and decreased activity in the amygdala (Creswell et al., 2007).

Mindfulness is key to trauma work not only because of its regulating effect on the nervous system but because it also facilitates the capacity for “dual awareness” or “parallel processing,” allowing us to explore the past without risk of retraumatization by keeping one “foot” in the present and one “foot” in the past (Ogden et al., 2006). “Dual awareness” is a habit of mind or mental ability that allows us to simultaneously hold in mind more than one state of consciousness. When the client can stay present in a mindfully aware relationship to both present moment experience and an implicit or explicit memory connected to the past, he or she is in dual awareness. When individuals can connect to a felt sense of the child self’s painful emotion while simultaneously feeling the length and stability of the spine, the in and out of the breath, the beating of the heart, and the ground under their feet, intense emotions can be held and tolerated. Sensorimotor Psychotherapy, Internal Family Systems, and hypnotic ego state therapy (Phillips & Frederick, 1995) are all mindfulness-based methods, as are the other popular treatments for trauma most frequently sought out by clients—Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) (Shapiro, 2001) and Somatic Experiencing (Levine, 2015).

From Whose Perspective Should We Observe?

Observations of the environment through the telescopic lenses specific to each part often create a distorted perspective for the client. Each part has particular biases that narrow what it picks up as data and what it never sees. The fight part is not scanning for safety cues: it is hypervigilantly oriented toward threat stimuli. Attach sees only the warm smile, the reassuring words, the polite manners—and never sees the danger signals that indicate grooming or seduction. The submit part doesn’t see the respect of his colleagues, the approval of his boss or family members, but he is likely to be hypersensitive to data that confirm beliefs in unworthiness or not belonging. When clients learn to identify the lens through which they are looking (“the little part is hoping to see someone who likes her,” “the depressed part is looking at Susan’s expression and thinking the worst”), they can begin to see the actions and reactions of their parts from a meta-awareness perspective. Rather than being flooded with overwhelming emotions, they learn to separate from the intense reactions of a part, acknowledge the feelings as “his” or “her distress,” and bear witness to the child part’s painful experience. Perhaps for the first time, clients can have a relationship to a distressing feeling rather than being consumed by it or identifying with it as “mine.” The feeling or reaction is still palpable but with a decrease in intensity that is consistent with the ability to sustain curiosity and interest in it, rather than react. Mindful “interest,” rather than “attachment or aversion,” helps individuals tolerate emotions and sensations that may have previously felt frightening, and it supports a neutral stance toward whatever is observed or discovered. In addition, when individuals become curious and interested and focused on what they are observing, they intuitively slow their pace to increase concentration and observational capacity. Being “interested” is the first step toward getting to know another being, even when that other is a part of one’s self. From this new perspective, it is easier for most individuals to find ways of soothing the parts’ emotions and anticipating events or triggers that might overwhelm a child without support from someone older and wiser.

In an Internal Family Systems approach (Schwartz, 1995; 2001), the observer role is ascribed to “self,” an internal state that draws upon eight “C” qualities: curiosity, compassion, calm, clarity, creativity, courage, confidence, and connectedness. “Self” is not just a meditative state or dependent upon having positive experiences in life: each quality is an innate resource available to all human beings no matter what their past or present circumstances. Most importantly for the purposes of psychotherapy, access to these states creates an internal healing environment.

In the model I am describing here, integrating approaches drawn from Sensorimotor Psychotherapy and Internal Family Systems, there is also a fundamental assumption that these “C” qualities are accessible to any human being. They are never lost, no matter how sadistic and prolonged the traumatic experiences. However, I find that, for many lower-functioning clients with habitually inhibited precortical activity, it may be necessary to practice in order to access these states consistently. Some individuals may have to learn how to regulate autonomic activation sufficiently to keep the prefrontal cortex online before they can connect even to their curiosity. Some clients may be triggered by feelings of compassion, calm, courage, even curiosity. In these instances, I ask the client to pick one of the “C” qualities from Internal Family Systems and just focus on the practice of accessing that quality.

Sarah at first picked compassion but quickly found that she felt so overwhelmed when she opened her heart to the young parts that, in the end, she couldn’t feel for them because she was too blended: she felt only the tidal wave of their emotions. Then she chose calm as the quality she wanted to cultivate but found that triggering, too. “I think it’s too close to having to be quiet and not move,” she realized. Finally, as her third choice, she picked curiosity. That didn’t trigger the parts, but because she blended so quickly with their intense reactivity, she often missed the chance to be curious. For her, it was easiest simply to observe her body responses: to mindfully notice when she was triggered and observe the activated thoughts, feelings, and body sensations as “things of interest,” rather than interpret or describe them in a narrative.

Adopting an attitude of mindful noticing or dual awareness also allows clients to slow down their thoughts, feelings, and physical reactions enough to listen more attentively to the parts. The therapist at first must support them by prompting them to “notice what’s happening,” “notice ‘who’ is here with us,” and by observing each thought or feeling as a separate communication: “I hear a part of you speaking today that feels overwhelmed and scared—do you notice that part, too? Can you be curious about what’s scaring her?”

“See how that ashamed part immediately interpreted the chaos in your apartment as her fault! Maybe because the critical part was having such a fit about it …”

“There’s quite a battle going on today inside you, huh? A lot of thoughts focused on whether or not to commit to your boyfriend—a lot of emotions and tears coming up. Notice the perspectives of both sides: what part wants you to stay connected no matter what? What part is afraid of him leaving? What part thinks you should get out while the going is good?”

“The hopeless part is really struggling today, isn’t he? He doesn’t want to feel this way—he doesn’t want to be stuck in the past—but hopelessness and shame are his ‘safe place,’ and he’s afraid it’s not safe to have hope.”

Differentiating Observation versus Meaning-Making

As Donald Meichenbaum (2012) reminds us, trauma is an experience beyond words, and the beliefs or stories that individuals attach to a traumatic event bias their meaning-making, leading to what he calls the creation of “self-defeating stories.” Which parts might write a self-defeating story?

The submit part would be likely to write a shame-based, hopeless story of victimization; the cry for help part a story of how no one came or cared; the fight part would communicate that it’s better to die than to continue to be used and abused. Only the going on with normal life with its access to the wider perspective of the prefrontal cortex has the ability to conceptualize at a higher level, to make meaning out of the apparently paradoxical feelings, beliefs, and instinctual reactions of the whole system. It requires higher order cognitive processing to comprehend that the belief one is “faking it” might be adaptive in a traumatic environment, while continuing to believe it later in life would be maladaptive. When beliefs are consistently differentiated from feelings, visceral reactions from perceptions, tension from relaxation (Ogden & Fisher, 2015), and when all of these inputs are connected to the parts contributing them, clients begin to get a clearer sense of who they are as a whole and the trauma logic underlying their actions and reactions.

Blending, Shifting, and Switching of Parts

Parts do not wear name tags, nor do personality systems come with road maps or instruction manuals. Every part of the client shares the same body, the same brain, the same environment. When we have a feeling or thought, it could be the expression of any part. To know “whose” feeling or thought requires familiarity: a personal relationship with the part that allows immediate recognition when we hear its voice. Or to know requires that we pause, listen carefully, and piece together the data or clues: which part would have reacted to that trigger? What kind of part would feel ashamed right now? But any of these acts of curiosity and interest are impossible when we identify with the part, when we “blend” with its feelings and reactions, interpreting them as our own. The term “blending,” created by Richard Schwartz (2001) and used in Internal Family Systems, refers to two confusing phenomena described by trauma clients: the tendency to identify with parts (“I am depressed,” “I want to die.”) and the tendency to become so flooded with their intense feelings and body responses that who “they” are and who “I” am become indistinguishable.

Catherine was on vacation with her husband in the Caribbean, a place they’d visited many times before and to which both felt a deep connection. The second morning of their trip, she woke up to inexplicable feelings of loneliness. She felt sad and empty, far away from her husband, even though he was only inches from her. “Believing” the feelings were hers, she found herself interpreting them: “He really doesn’t understand me—he means well, but he’s not really there for me.” By the time her husband woke up, she was in tears, accusing him of not truly caring. Only later in the day, when she was better connected to her normal life part, did she realize that the lonely feeling came from a young part who, disconnected and split off from Catherine’s present day life, didn’t experience the safety, support, and companionship she’d found in her marriage. The little part just needed reassurance that she wasn’t all alone.

Catherine had not only become blended with the young part but had shifted into an altered state during her dream sleep so that, on awakening, she was in another time and place. Now in the implicit memory state of a little girl in a very lonely, frightening family environment, she lost any connection to her present day perspective altogether. Gone was her happy marriage, gone the successful creation of a new life, a new safety, and a new family in which she was welcome and valued. She was back in Michigan, and it didn’t feel safe.

Rachel alternated between feeling depressed and feeling irritated—sometimes irritated more with herself, sometimes annoyed by others. The depression took hold most powerfully when her partner, Susan, was busy with work and friends, leaving little time or energy for Rachel. At such times, the depression often convinced her that it would be better to die than to live, but, knowing how much it would hurt her partner to lose her, she would fight the impulse to act on her suicidal feelings. When she felt the irritability, on the other hand, she lost the empathic perspective toward her partner: feeling annoyed and “morally correct” in her judgment, she had no qualms about hurting Susan’s feelings. The depression and abandonment feelings were triggered by the loss of Susan’s attention, whereas the critical feelings were usually triggered by Susan’s tendency to “rescue” friends and family who “needed help,” even if it meant being disconnected from Rachel and absorbed in the crises of others.

When Rachel was asked to notice the depression as a depressed part and to be curious about how old that part was, the number “12” immediately came to mind. “That was a tough age,” she recalled. Asked to focus on the depressed 12-year-old and to notice what other feelings went with the depression, Rachel could feel a sense of not belonging, of not being wanted or worthy of notice, as well as fear that being noticed might bring something bad instead of good. During her childhood, Rachel’s mother could barely manage the stress of having six children she hadn’t truly wanted; being noticed was a mixed blessing because more often than not, it led to anger or demands to perform rather than reassurance and closeness. It made sense that this part would be triggered by a partner who had too many people depending on her. Despite how loving and validating Susan tended to be, Rachel’s 12-year-old part held a different reality. When Susan was busy, she re-experienced the implicit memories of a cold, unaffectionate mother whose attention was divided. When asked to notice the irritability as another part, Rachel immediately thought of her mother: “Oh, my God! The irritable part sounds just like my mother—frugality and avoidance of “excess” emotion were moral issues for her.” When she was asked to “unblend” or mindfully separate from the irritable part and notice it as a part, she became aware that “she” (i.e., her normal life self) prized the unconditionally accepting relationship she and Susan had developed much more than the judgmental part did. The judgmental part was still trying to enforce her mother’s rules decades later, Rachel realized with a laugh—as if her mother’s approval were still necessary for survival!

Rachel exemplifies the phenomenon of “blending,” while Catherine exemplifies “shifting” of mental states. Rachel could easily reality-test her perceptions; she could step back from them; and she could even be curious about why she was having such strong reactions. Catherine, on the other hand, experienced palpable changes in both emotional state and perspective during which she had no memory or connection to other feelings and states. On the first day of their vacation, she had felt a sense of appreciation for being in such a beautiful place with a loving, supportive husband. But after “time-traveling” in her sleep, she woke up to profound feelings of loneliness. There was no curious “Why am I feeling this way?” in her mind, only a frantic sense of urgency to end the painful feeling.

Nelly, on the other hand, had dissociative identity disorder (DID) and often “switched” from state to state, a cardinal symptom of DID in which changes in state are sudden, frequent, and often accompanied by losses of consciousness. (For example, had Catherine “switched,” she might not have recognized her husband at all; she might not have known where she was or even how old or what her name was.)

When Nelly was “in” her depressed “default setting” part, there was no other reality, no other perspective. During the day, she found she could switch states by making lunch dates with friends. Their affection and interest acted as a positive trigger, facilitating a switch into her going on with normal life self. One moment, she would feel shame and self-loathing, questioning why she had made a lunch date at all, then, as soon as her friend arrived, the normal life part that had made the appointment would be present. At night, feeling better after seeing her friends, “she” would make a commitment to herself to get up in the morning and start the day, no matter how badly she felt. But when she woke up “hijacked” by the depressed part, she would have no memory of the commitment “she” had made the night before. Then “she” would go back to sleep, not wanting to face the day, and when “she” woke up again in the early afternoon, the ashamed part would feel “pathetic” and inadequate. It was not important that Nelly’s dissociative disorder be diagnosed, but identifying the switching was important. Without realizing that she switched, she could only interpret her behavior through the lens of failure.

All of these clients, regardless of diagnosis, were learning to separate from the feelings, beliefs, activation, and body responses of their parts, rather than automatically assuming that all of their mental and emotional life belonged to one self. They were practicing mindful noticing and the ability to identify parts as they appeared moment by moment rather than identify with those parts as “who I am.” Over and over again, they became aware that each time they noticed a part as “she” or “he,” rather than automatically identifying with its feelings, they felt some relief—a little or even a lot. When, in addition, they became more deeply curious about a part, they began naturally to feel compassion toward him or her—in spite of themselves or in spite of the parts that were hostile toward the other parts. There was a gain in perspective, a feeling of greater calm, and that calming would often “turn on” the prefrontal cortex, facilitating more creative solutions to problems that represented internal conflict between parts.

Facilitating Empathy

Not only does the therapist model bearing witness to each part’s qualities, emotions, and trauma-related perspective, she or he must also provide the missing link of empathy for each part. Knowing that simply observing and naming what they observe as a “part” is challenging enough for clients, I try to model mindful use of the language of parts. I notice their “voices,” feelings, and points of view, often before the client does, name their appearance, and then I deliberately add a tone of warmth or communicate pleasure and appreciation for each part. I describe their plight (“What was a little boy supposed to do?”) when clients are struggling with compassion. I try to verbalize appreciation for their contributions to the client’s survival: “Had he not given up and given in, what would have happened to all of you? How would your stepfather have reacted?” Most importantly, I share my own personal experience of the client’s parts to bring them alive and make them “real.” Using language that evokes positive feelings and associations, I try to communicate that they are much more than disembodied implicit memories without a context. I might admire the ingenuity of a very young part: “That little girl was one smart cookie, wasn’t she? Oh my!” Or the courage of an adolescent part: “That 15-year-old was one determined young lady, huh? But, you know, she was always very creative, too—who would have thought to ‘hide out’ in a hospital where her parents couldn’t get to her? It was pretty amazing how she pulled that off. It’s not so easy to keep being admitted to hospitals to get away from your parents!” If we are speaking about an adolescent male part, I might say, “Wow, he took some big risks. Always getting in trouble so he could get help for all of you when he could have been killed.” I can also cultivate empathy by “defending” or “sticking up” for the parts, as in the following example:

Nelly responded to my helping her notice the depressed part by judging its behavior: “Well, she’s a loser—she doesn’t let me even get out of bed!”

I immediately challenged her: “Are you suggesting a depressed 11-year-old part chose to be this way? She volunteered at birth to be a ‘loser’? [I raised my hand as if to volunteer, and we both laughed.] No baby in the crib volunteers to be depressed or to hate herself … let’s be curious about how she lost her hope …”

“Seeing” the Parts: Externalized Mindfulness

When individuals are too identified or too blended with the their parts’ feelings and beliefs to access mindful observation, as is common with very dysregulated clients, therapists need other ways of facilitating dual awareness—enough dual awareness that the normal life self develops a perspective on and a relationship with the trauma-related part rather than blend with it.

There are a number of ways to achieve dual awareness, even in very decompensated individuals, but all depend upon multi-modal interventions. Because visual focusing seems to increase curiosity and activate the medial prefrontal cortex, trauma therapists can benefit from including an easel or large clipboard as part of their office equipment (as I do). For example, I might ask a client to draw a picture of some part with which he or she has been struggling and then invite the client to look at the picture with curiosity: what does the drawing tell him about this part? What is he learning from the drawing that challenges what he’s previously believed about the part? How does he feel toward this part now?

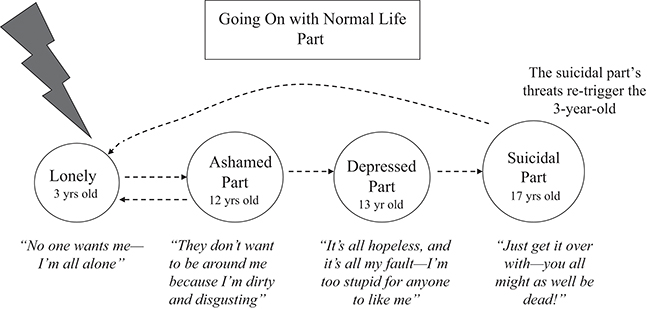

Or we can help clients decode struggles between parts by creating a “flow chart” that tracks the internal relationships between the parts in conflict, starting with an initial trigger and then noting step by step which part or parts were activated. Drawing a rectangle at the top of the page to depict the going on with normal life self, clients are asked to observe retrospectively, frame by frame, the sequence of triggers and parts that set the internal conflict in motion. The trigger is usually represented by a large arrow shape that I color in red. Next, the client is asked to recall which part reacted first to the triggering stimulus, and that part is depicted by a circle within which the therapist can write the approximate age or some description of the part (i.e., “depressed part,” “anxious part”) by which to recognize it in the future. The therapist next asks: “How did this part react to [the trigger]? How did he feel?” Then the therapist writes down the words connected to that part below its circle, making sure to identify its feelings and beliefs: “Believes she is disgusting and worthless—‘just wants to crawl into a hole’.”

Following that, the client is asked to observe, “What part got triggered by the ashamed part?” For example, Nelly would have said, “Then the hopeless part gets triggered: she just keeps saying, ‘It’s all bad and it will never get better.’” That part in turn gets represented by a circle within which is written its age and “name” or descriptor and below which are the words that describe its perspective and emotions. Typically, internal struggles occur between 3 to 6 different parts, and the flow-charting continues until a full picture of the conflict or problem emerges and can be appreciated. In the following example, the client came in feeling distressed and suicidal, so dysregulated that she could not unblend from the parts, so I asked her if we could diagram what was happening so “we can both really ‘get’ it—we know there are some pretty distressed parts, but we don’t understand what’s triggering them.”

Clients rarely refuse to diagram because it tends to feel less threatening than talking about their emotions, but I can add, “And if we start diagramming, and you find it too overwhelming or not helpful, just tell me.” “Let’s start with what happened first—there was some trigger, and then the first feelings you felt were … what?”

CLIENT: “I felt so lonely and unwanted—like no one was there—I’ve just been abandoned.”

ME: “A little part was triggered, huh? [While she talks, I draw a circle for the young part and describe her distress in the same words used by the client.] Back to that place of painful loneliness where no one wanted her. How sad! And then what happened next? What part came up next?”

CLIENT: “Then I felt such intense shame—it was overwhelming—I felt so disgusting and dirty that no wonder no one wanted me.”

ME: “So the little part triggered the shame part and the shame part blamed herself! And not just for the little part’s being alone but for everything—she just took it all on her shoulders. It was all her. That’s what she does, doesn’t she? She always assumes it’s her.”

Much like the diagram in Figure 5.1, what feels like an internal struggle to the client usually appears in the diagram as a series of parts, each of which triggers each other in succession, leading to some impulse to give up, hurt the body, die, or run away—some desperate measure for what feels like desperate times.

The visual images symbolizing each different part and his or her feelings tend to spontaneously invite unblending. As they study the diagram, I can often see a shift in clients’ body language or tone of voice indicating to me that the normal life self is noticing the parts instead of blending with them. And if unblending does not occur spontaneously, I can ask the client to focus specifically on each element of the drawing separately and increase curiosity about each part, observing each set of feelings and thoughts and noticing how each has made meaning of the implicit feelings triggered by other parts.

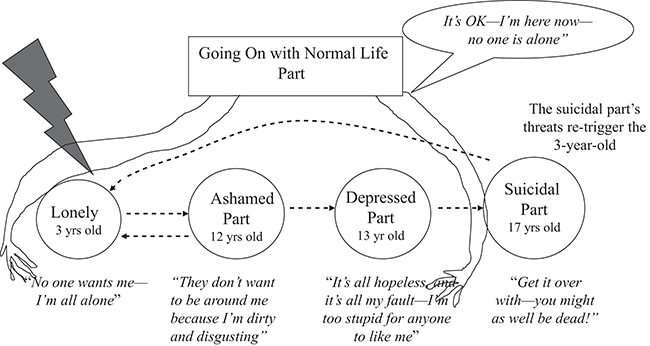

“Notice how it all began when your boyfriend was late, and he triggered the little part—she was so hurt! She felt so disappointed and unimportant, and then the hopeless part triggered her more and triggered your fight part—and she was beside herself! Can you see how it worked?” Observing on the diagram how suicidal, addictive, acting out, or self-destructive parts get triggered by the emotions of the vulnerable parts and then emerge to offer the young parts a “way out” of their distress further clarifies that the underlying purpose of trauma-related self-destructive behavior is to bring relief and regulation to the body: the very opposite of trying to die. Once curiosity and even compassion are elicited, the next step is to diagram a solution—in this case, a solution for the lonely part and a solution for the suicidal part. A solution or intervention is always best if it emerges organically out of the concern or protectiveness of the going on with normal life self (Figure 5.2).

The first diagram(s) depicts for the client how the system of parts became activated and polarized as a result of the triggering. The second diagram is used to depict how the normal life self can now provide healing and care for the child parts, making the suicidal part’s “attempt to help” unnecessary. Had I treated the suicidal part’s “offer to help” as life-threatening suicidal ideation and tried to hospitalize the client, both the fight part and the attach part would have been further triggered. The attach part would have felt more alone, banished to the hospital, and the fight part would have felt hostility and entrapment by a controlling authority figure.

In this example and many others, the solution to what could have been a life-or-death crisis results from a comforting reparative experience being offered to the vulnerable little part. A compassionate normal life self is asked to take the lonely, ashamed, hopeless child parts “under her wing,” communicating a sense of care and protection. Even if the client is struggling with compassion, the visual image of the arms encircling the young parts evokes positive sensations in the client’s body: warmth, protectiveness, a smile, the impulse to move toward the drawing and thus the parts. The advantage of the diagrams is the ability to introduce something foreign and potentially challenging through non-verbal communication. Had I asked this client to say, “I will take care of you,” to the younger parts, I might have received the answer: “No, I don’t want to take care of them!” But when I draw the arms and describe the intervention as a gesture, “See what happens when you take these young parts under your wing so they aren’t so overwhelmed and scared,” no client protests. As I speak, I make a gesture with my right arm as if taking someone under my wing, and I repeat the gesture again each time I say the words “under your wing.” The somatic communication speaks directly to the parts themselves. The left brain, specializing in words, may react negatively to the verbal communication but cannot block the somatic message intended for the right brain (Gazzaniga, 1985). The younger parts can feel the “wing” in the drawing and in my gesture.

Another means of externalizing the parts’ struggles and conflicts so they can be witnessed is to use objects to represent them: sand tray figurines, animal figures, stones and crystals, even rubber ducks. Notice that all of these figures are appealing to a child’s mind, not just an adult mind and body. The therapist must never forget that the client is not a “he” or “she” but is a system composed of parts of all ages from infants to wise elders.

Cath came for a consultation to assess whether a DID diagnosis would be more appropriate for her than psychotic disorder, the label given to her each time she reported hearing voices. She was challenging to interview, though, because she was constantly distracted by what seemed to be a very heated internal conversation among her voices. Her mouth moved as if she were talking, though she emitted no sound; she would gesture as though angry, a scowl on her face. Occasionally, I could read her lips as she shook her head vigorously and mouthed “No, no!” Each time I used the word “part” or asked her about the voices that were talking to her, the dialogue might pause for a moment, but there was no clear sign I had been heard—until the third appointment to which Cath came carrying a little plastic bag. “Here, these are the parts,” she said, and she dumped the contents of her little bag on the table and promptly returned to her internal conversation. A small pile of miniature rubber ducks sat on my coffee table, a gift from Cath representing the parts she couldn’t yet tell me about because she was too overwhelmed by their sheer number and the intensity of their feelings and conflicts.

Following that session, Cath gradually learned to describe her week-to-week internal problems and conflicts using the ducks, choosing different sizes and colors of little rubber ducks to represent different parts. Weeks later, she even brought in a rubber stress ball in the shape of a human brain to represent, “that big brain you keep talking about,” proof that she had been listening to me after all when I talked about the “wise mind” part she had in her grownup brain. Each week, we would address whatever issue she brought in by using the ducks to create a psychodrama-like sculpture that depicted how inner conflicts between parts had resulted in a crisis or problem. Then I would describe duck by duck what she had shown me:

“When the little orange duck [I pointed to it to focus her attention] got triggered by the angry man at the post office, the green duck started to run out of the building, which freaked out Jeremy [the medium-sized red teenage duck]. He thought the man was after him, so he jumped in the car and started driving away too fast, and that scared all the young parts! He drove so fast, and he was so mad and scared that it frightened the other ducks even more. What they need is to have the big brain help them at the post office so the angry man doesn’t yell at them. What does the part with the big brain think should be done about this? The child parts like to go to the post office, but they always get yelled at because people get confused when child parts are talking in a grownup’s body. They think the grownup is being weird. Maybe they shouldn’t be going into stores alone without a grownup—what do you think?”

Invariably, with some coaching from me, the rubber brain would come up with a creative solution that reflected wider perspective-taking made possible by Cath’s being able to observe the duck tableau’s depiction of the whole system and the whole of an experience. The internal intensity and the “noise” of the voices made it difficult for her to be mindful, but she could focus on the ducks and access more curiosity. Cath began to see the patterns of chaos and crisis that resulted when she switched into younger parts and then they were triggered by an external stimulus. Their hyperaroused emotional reactions would then trigger the defensive responses of fight and flight parts like Jeremy, retriggering the young parts all over again. Whether achieved through mindful observation, drawing, diagramming, or “duck therapy,” externalization or visual depiction of the parts in interaction facilitates a wider field of awareness, greater curiosity and interest, a sense of perspective (“I’m safe now even though my parts don’t believe it”), and increasing capacity to access the better judgment of the wise mind.

Blending and Reality-Testing

Because her survival strategy had historically been to automatically blend with whatever part was activated in a given moment, Annie had never questioned the information she regularly received through her body (tension, held breath, elevated heart rate, shaking and trembling), her thoughts (disparaging, hopeless, scathing), or her emotions (shame, panic, dread). Small, unremarkable daily events, including positive experiences like being asked by a potential friend to go to lunch, repeatedly triggered the parts and their implicit memories, which triggered other parts. “That’s why it’s easier to have a beer at 10 in the morning and go back to bed.” For example, being invited on a lunch date triggered an insecure child part afraid she wouldn’t know how to act, which then triggered hypervigilant parts guarding childhood secrets by discouraging close friendships, which then triggered judgmental, humiliating parts: “How stupid! What a ridiculous idea! Why would anyone want to be friends with you? She’ll see how dumb you are in a minute.” Between the sense of danger evoked by normal life triggers and the shame triggered by the judgmental parts, it was natural that, in her blended state, Annie assumed her world must be humiliating and dangerous and she was defective and unwanted.

Blending Keeps the Trauma “Alive”

How could any individual resolve traumatic experience in what subjectively feels like an unsafe, hostile environment? Clients and therapists alike often collude in believing that trauma can be resolved by processing the events even when critical voices are still attacking the individual at will, using the same words or scathing tone as the perpetrator. Similarly, both may equate “safety” with freedom from self-harm or a non-abusive home environment, as I did when I first met Annie. It might not occur to us that a “felt sense” of safety is likely to be unattainable if the client is habitually blended with child parts who still feel unwelcome, frightened, or ashamed or suicidal. Although the external environment may now be safe from an objective perspective, clients who are blended with their implicit memories and parts may have no bodily or emotional sense of safety that could reassure the parts that “it” is over. Before trauma can be resolved, the client must learn how to unblend from parts so that the realities of both brains can be appreciated. From an unblended, dual awareness perspective, the normal life self can learn to orient to the immediate environment by focusing visual attention, can correctly evaluate the level of safety, but also feel the parts’ fear and bracing for danger as “their” evaluation. From the perspective of “present reality,” as I call it, the normal life part can bear witness to the parts’ past reality and often feel empathy for their still being “there.”

Learning to Unblend

Because it takes practice to detect when one is blended, often the therapist becomes the observer who notices blending: “Hmmm, I can see you’re really blended with the ashamed part today,” “It’s hard not to blend with that anxious part—you’re so used to ‘insta-blending’ with her.” “Insta-blending” is the term I use to describe procedurally learned habits of automatically blending with whichever parts have the strongest feelings, often so quickly that mindful noticing doesn’t catch it. To be able to identify these patterns as they happen, it is important for clients to have a language for what is happening to them that is non-interpretive and non-pathologizing and helps them to notice potentially problematic conditioned learning. Clients also benefit from “unblending protocols,” skills and steps for what to do after they’ve noticed that they are blended. (See Appendix A for a model of unblending protocol.)

Suzanne came into her session with the guarded facial expression I had learned to expect as the expression connected to her hypervigilant part. This “bodyguard” part was always primed for disappointment or betrayal, both of which had been daily experiences in Suzanne’s childhood. “I can’t do it,” she said. “I can’t do it. I can’t do what you and Dr. G. want from me.” (Both her primary therapist and I had been trying to help her learn to unblend, but she was more often blended than not.) “Why do you keep trying to make me do something I can’t do?!” As she spoke, her voice got more emotional and higher-pitched, a sign to me that this was a part speaking.

ME: “Notice the part that keeps saying, ‘I can’t—I can’t!’ Can you separate from that part a little bit? See if you can feel her without ‘becoming’ her … so she knows you’re hearing her.”

SUZANNE: “No, I told you, I can’t do that stuff you guys want me to do!”

ME: “Suzanne, I know it’s hard to learn to unblend when you’re so used to thinking of all these parts as ‘just you.’ But would you be willing to try something? [She nods.] See what happens if you say, ‘She is afraid I can’t do it—she’s afraid.’ What happens?”

SUZANNE: “It’s not quite as intense.”

ME: “Yes, it’s not as intense when she hears you say, ‘She’s afraid.’ Can you keep saying ‘she’?”

SUZANNE: “OK.”

ME: “Ask her: what is she worried about if she can’t ‘do it’?”

SUZANNE: [pauses, appearing to be listening inside.] “She’s afraid you’ll give up on her and then you won’t help her.”

ME: “Of course, she’s worried about that! Because she had a mother whose motto was ‘my way or the highway,’ that’s always a worry for her, isn’t it?”

SUZANNE: “But it feels like my worry, too. Can I tell you the problem I have with this unblending thing? When I try to do it, when I step back from the parts’ feelings, then I can’t feel them at all. I just feel numb. Either I feel all of it, or I can’t feel it at all.”

ME: “Well, that is a problem, isn’t it?” [Note that I validate her issues with unblending as normal and natural, trying to imply that my standards are different from her mother’s.] “If the little part hadn’t been so worried that we would reject and abandon her, maybe you’d have been able to tell us about this problem. And it’s such a common one.” [I now shift to some psychoeducation for her normal life self as a context for understanding her difficulties in unblending.] “Many trauma survivors find it hard to have what we call ‘dual awareness’: awareness of your being and awareness of the parts’ feelings at the same time. But let’s see if I can teach you some ways of unblending that might help with that. Would you be willing to try five steps to unblending?” [I deliberately chose a very structured approach, broken down into concrete small steps, to make the learning easier than she was primed to expect.]

SUZANNE: “OK.”

ME: “First, notice the feeling of ‘I can’t’—can you still feel it?”

SUZANNE: “Yes, I can—it’s not as intense, but it’s still there.”

ME: “Start by noticing the feeling and repeating again, ‘She’s afraid I can’t do it.’ That’s Step One.”

SUZANNE: “Say it out loud or to myself?”

ME: “Whichever feels more comfortable for you. If you are feeling distress, just assume that it belongs to a part and say to yourself or out loud, ‘She’s afraid … or ‘She’s upset.’” [I give her a minute or two to try out this new language with herself.] “Is that better or worse?”

SUZANNE: “Better.”

ME: “Ready for Step Two?”

SUZANNE: “OK.”

ME: “Here’s Step Two: engage your core—slightly tense the muscles in your core so she can feel your presence. … Can you still feel her?” [Remembering that Suzanne had been an athlete as a child, I chose to try out using the body as a resource here.]

SUZANNE: “I can!”

ME: “Great! Now ask her if she can feel you.”

SUZANNE: “She can.”

ME: “Wonderful! You can both feel each other! Great work! Hooray!! Does she like that?”

SUZANNE: “She does. She’s telling me that’s why the parts are so freaked out all the time—because they don’t think anyone hear them.”

ME: “A good reason for us to work on this, huh? Now you are both ready for Step Three! OK, now lengthen your spine a little bit from your lower back up—like you’re putting space between the vertebrae … Ask her if she can feel how tall you are now …”

SUZANNE: “She’s surprised—she didn’t know I was that tall.”

ME: “Good work! Now you can feel her, and she can feel you, and you’re talking! Does she like that?”

SUZANNE: “Yes, she likes it a lot. And I like it because I hate it when I try to unblend and then I can’t feel the part at all.”

ME: “Ask her if it feels good to hear you say that you want to be able to feel her with you.”

SUZANNE: “She likes that, but she says she’s still worried that I won’t get it, and you and Dr. G. won’t like her …”

ME: “Good, I’m glad she can tell you her worries. That’s a good thing. Just be careful not to blend with her worries. Let’s practice Step 4: connect to your department supervisor role for a moment. Imagine that this part is coming to you as her supervisor, and she’s worried that she’s not getting things fast enough and that she’ll be fired. What would you tell her?”

SUZANNE: [Thinks for a moment.] “I’d tell her not to worry—to just keep trying to learn the job and trust that if she keeps trying, she will get it.”

ME: “Wonderful advice, Suzanne—your staff are lucky to have such a wise, compassionate supervisor—now to Step 5: ask her if it helps her to hear that or if she still needs something else.”

SUZANNE: “She says it does help, she wants me to keep saying it because she needs to hear it over and over …”

ME: “Good point! She hasn’t heard it often enough in her life to believe it and take it in. Do you think you could remember to keep telling her that she’ll get it if she keeps trying? Would it help if you put it on your calendar and asked your phone to remind you? I know you keep track of your kids’ schedules that way, and this part is a kid, too.”

SUZANNE: [now clearly in her going on with normal life part] “I’ll put her in my schedule, but it would also help if you wrote down those five steps for me so I can remember and practice.” [This request told me that her normal life part was more present than I had seen before: she could think about how to achieve a goal that involved the parts.]

ME: [Talking as I write down the five steps we just practiced.]”That would definitely reassure her, Suzanne! And now, before we end today, let’s thank her for telling you she was so worried! That was important. How else would you know? Maybe we can also schedule a time for her or other parts to tell you about their worries … Let’s be thinking about that.”

Less afraid to connect to her young self because she was provided with a set of structured steps and not expected to connect to “too much” vulnerability too soon, Suzanne was able to not only unblend but also begin a dialogue with the little part who had been so upset. Like Suzanne, clients often spontaneously experience compassion for their parts once they are no longer blended with them: “I feel really sad for her—I want to just pick her up and hold her.” Here, the therapist might feel tempted to stay with the emotion of sadness rather than continue with the parts focus. But the therapist’s role at this point is keep the client in a mindful state and centered on the child: “What is it like for her to feel your sadness for her? To feel that someone actually cares how she feels?” “See what happens if you reach out to her and just offer your hand.” As clients imagine reaching out to their younger selves or even make a reaching out gesture, a technique drawn from Sensorimotor Psychotherapy (Ogden & Fisher, 2015), their internal state usually transforms: they feel a sense of warmth; their bodies relax; they feel calmer. To ensure that these positive internal states are more than momentary, the therapist must continue focusing on “what happens inside” to deepen the felt connection to the child part and increase closeness and compassion.

Sometimes clients become expert at saying all the right words to their parts but without an embodied connection to the words or the part. It is very important that the therapist ask clients to linger on the changes in emotion or sensation that occur when the normal life self says or does something nourishing or comforting for the parts. He or she can ask, “What changes in her feelings when she senses you are really ‘there’?” Or ask her, “How can she feel that you are sincere? What tells her that?” Sometimes, the therapist has to interweave psychoeducation with the parts work, as I did with Suzanne above, to make the point that change will come only through repetition of new patterns: “The more you hold her, the safer she will feel, and then the calmer you will feel. She can’t let you feel calm and centered if she’s terrified.”

Sometimes, the child’s predicament has to be “translated” by the therapist to help the normal life self “get it”:

“She’s saying that she likes you here with her, but she doesn’t trust it yet. … That makes sense, doesn’t it? Can you feel her holding back a little? It just means that she’s been through a lot—as she certainly has, right? And that makes it hard for her to trust. For her to believe that someone will really be there for her, you’ll need to keep on showing up, day after day after day, communicating that you care how she feels. That’s what she would need to truly believe you are there for good, and she can finally relax and feel safe.”

Providing Hospitality

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, when early experts in dissociation were trying to put words to what they observed in patients with “multiple personality disorder,” the term chosen for what we now know as the going on with normal life self was “host.” Although that label was meant to convey the sense of an empty vessel holding the traumatized parts, another meaning we could assign to the term “host” is that of homeowner and provider of hospitality. In fact, if the going on with normal life self is in charge of the body’s health and well-being, must provide food, shelter, and other necessities, and is focused on present moment priorities, it is quite literally the “host” or home base for all parts of the self. In addition, given its access to the medial prefrontal cortex, the going on with normal life self has the unique ability to see a wider perspective, to conceptualize, to reconcile opposites or at least keep them simultaneously in mind. The normal life self has the capacity to hold in dual awareness both past and present, part and whole, animal brain and thinking brain. However, when clients finally come for treatment, the going on with normal life self is often demoralized or depleted, identified with certain parts and intimidated by or ashamed of others. Although the normal life part has the innate ability to learn to observe them all, to decrease autonomic dysregulation, and to become interested in rather than afraid of the parts, he or she may need education to recognize them as young child selves trying to communicate their trauma-related fears and phobias.

Welcoming the Lost Souls and Traumatized Children

But why should the normal life self become a warm and welcoming host to trauma-related parts when they are turning his or her daily life upside down? Just as therapists have to make a convincing case that connection to emotion or remembering the past or practicing skills is of benefit to clients, it is our job to make the link between the hopes and dreams that brought the client to therapy and the ability to recognize and befriend the parts. Think about what the client is seeking from therapy: what is the wish that drove her to your door? What is he hoping for as a result of treatment? Why is he or she here? Is this client seeking relief or self-actualization? Trying to stay alive or trying to make meaning of his or her experience?

Notice that each explanation I give to a client is generally positive, normalizing, and speaks to the “best self” of the client:

“I know you wish the parts would just go away, but would that be fair? To neglect them the way you were neglected? I don’t believe you’re that kind of person. The person I know you to be would never reject wounded children because they were upset or inconvenient.”

“Think of the parts as your roommates—you all share the same body, the same home. You have a choice: you can learn to accept each other and get along, or you can struggle to win every battle!”

“We wouldn’t be sitting here today if it weren’t for your parts. By taking on the survive-at-all-costs role, they allowed you to leave home, go to college, and start a life far away from the world of your childhood. It’s only fair to take them with you to this better, safer world—it could be a way to thank them. It’s not much of a thanks to leave them ‘there’ while you go forward.”

“Rightly or wrongly, you and the parts are inseparable: as long as their distress becomes your distress. For you to live a life freer of fear, anger, and shame, the parts need to welcomed—they have to feel safe.”

Notice that the meaning-making of the therapist challenges the going on with normal life self while at the same time expressing support for the parts. Each statement or question communicates that the therapist will be an advocate for the young, vulnerable, and traumatized. There is no emphasis on discovering what happened in the past: the focus is on the relationship between parts and normal life self now, what is happening between them in the present moment. There is an implicit assumption that they are driven by the experiences of the past, by painful body and emotional memories. That can be acknowledged, but no effort is made to connect the parts’ reactions now to specific events then. When clients spontaneously associate a part with particular image or event, the therapist reframes the intrusion of memory as the part’s way of communicating why it is afraid or ashamed or angry.

“When we talk about the part that fears abandonment, that same image always come up, doesn’t it? That image of your mother driving away angrily, and this little part of you running down the street after her … I wonder if that little girl is trying to ask you, ‘Will you get overwhelmed and run away from me, too?’”

“If that image were a message from some young part of you, what would he be trying to tell you? Would he be saying, ‘Yes, that’s why I’m so scared all the time’? Or ‘Help me!’ or “Don’t let anyone hurt me.’ It’s important to know, isn’t it? Otherwise he’s going to have to keep giving you disturbing pictures to make his point.”

Initially, therapy sessions must be used as the opportunity to practice these new habits of noticing the parts, naming what is noticed, and unblending. But practice requires a therapist who will consistently ask: “‘Who’ is speaking right now? What parts are reacting to the conversation we’re having? What part is having this strong emotional reaction?” As noted in Chapter 4, most human beings are in the habit of assuming that all thoughts, feelings, and physical reactions are “mine,” that what “I” am feeling represents “my” emotions. It takes week-after-week practice to help clients relinquish that automatic assumption and learn instead to assume that anything they might be feeling or thinking could be an expression of any one of many parts.

To help individuals reclaim their fragmented, disowned, alienated parts, the therapist must be relentless and persistent in using the language of parts in therapy and asking the client to use it, too: “What happens when you say, ‘She is feeling ashamed’? Do the feelings get more intense or less?” Each time I invite clients to name what they feel as “his” or “her” feelings, they notice a slight relaxing or relief—as if by naming the emotion as “his” emotion conveys to the part a sense of being heard or being understood.

Most clients have evolved a procedurally learned habitual strategy for dealing with the intrusive or underlying communications from parts. Some try to control the intrusive feelings and impulses, ignore the tears or self-denigrating thoughts or voices. Others interpret each feeling, impulse, or belief as “my feeling” or “how I feel,” forgetting that they may have felt differently even seconds before. The former strategy yields a more emotionally cut-off, controlled way of being that interferes with the enjoyment of life. The latter leads to chaos or a feeling of being overwhelmed, out of control, crazy, on the verge of implosion or explosion. Not only do these patterns need to be noticed and translated into parts language, but it is also important that the therapy emphasize strengthening the normal life self and enhancing the qualities associated with “self” or “self energy” in the Internal Family Systems approach (Schwartz, 2001). The normal life self must develop the capacities of “wise mind”: staying connected to present time, capable of meta-awareness or the capacity to hover above, seeing all of the parts, and the ability to make decisions for the sake of the whole. The concept of ‘self’ in Internal Family Systems helps clients connect to states of compassion, creativity, curiosity, and perspective, while the going on with normal life self of the Structural Dissociation model emphasizes the importance of developing the functional ability to take action to implement decisions for the sake of the system. If we put the two models together and encourage the development of wise mind or “self energy” in the going on with normal life self, then we have leadership informed by clarity of view, compassionate acceptance, and the capacity for behavior change. The challenge is how to access a going on with normal life part and convince that aspect of self to not only assume a leadership role but also cultivate the qualities of self: curiosity, compassion, clarity, calm, creativity, courage, commitment, and connection.

Forming a Connection to a Wise Compassionate Adult

Because the actions and reactions of the parts are driven by autonomic activation and animal defense survival responses, it is common for survivors of trauma to “own” and become identified with some parts just as they disown other parts. Some identify with their normal life selves, as did Carla; some identify with their suicidal parts or angry parts; some identify with the attach part’s desperate proximity-seeking and end up “looking for love in all the wrong places.” Some identify with the submit part and become the caretakers even for family members who have abused them. But when clients identify with trauma-related parts or blend with them, they can quickly lose access to the prefrontal cortex and the normal life self. The intensity of the parts’ trauma responses tends to “drown out” a felt connection to the left brain self who can remember to grocery shop even though the freeze part is having panic attacks today. It is not surprising that the normal life self’s dogged persistence in making a normal life possible comes to be interpreted as “pretending” or “fraudulent.” It is counterintuitive to conceive of a part that thinks and acts rationally and functionally despite the overwhelming sensations and emotions as reflecting an authentic self, much less a self that embodies how the client survived the years of abuse, neglect, or captivity without losing the capacity or drive to “go on.”

Many clients immediately reject the concept of having a normal life self: “There’s no adult here—I don’t even like adults,” said the law student who came to see me for a consultation, promoting the agenda of the little part that needed care because she was “home alone” with no one. “I used to function,” said an artist. “I used to have a life but no more. I couldn’t handle things—I couldn’t function in so much pain.” After a romantic breakup, her depressed part became intensely hopeless and encouraged by friends and therapist to see it as grief, the artist blended with the depressed part, making it harder and harder to function.

I asked the artist, “Do you remember what it was like when you could function, when you had a life?”

CLIENT: “I do—I had so many interests and things I loved to do.” [Her face lit up.]

ME: “When you remember those days, what happens in your body?”

CLIENT: “I feel more energy—more hope—then I think, ‘Who am I kidding? There’s no hope for me.’”

ME: “That’s what the depressed part keeps telling you! And you believe her which doesn’t help either of you. Would you have done that with your students in art class? If one of them told you the same thing, would you have agreed with her?”

CLIENT: “No, of course not!” [Getting a bit irritated with me. But from a body perspective, irritation is an antidote to depression, so I am encouraged, not discouraged, by the irritation.]

ME: “What would you tell your student?”

CLIENT: “I’d tell her, ‘Do what you love—that’s all you have to do. Hope will follow from that, not the other way around.’”

ME: “Right, she doesn’t need hope to follow her heart! Good point. And if she does, she will feel more hopeful. See what happens if you tell that to the depressed part …”

Here, I could challenge the over-identification with the depressed part by accessing her normal life part’s career experience and inherent compassion. The left-brain wisdom available to her right brain depressed part was still there in her normal life self. Sometimes, when clients are as adamant as the law student that they would never have a normal life or adult part, I challenge them with a simple biological fact: “Unless you have had a brain injury you forgot to mention, or brain surgery, the normal life self is still alive and well in your prefrontal cortex [I tap my forehead to demonstrate where to find that part of the personality]—it’s still there even if you haven’t been able to function for years.” Or as I said to the artist, “I’m happy to tell you that the brain is like the Library of Congress—it doesn’t lose information. If you have ever had even a day or hour of curiosity or clarity of mind or confidence, those abilities are still within you. You’ve just lost access to them because the depressed part hijacked you just trying to get you to see how upset she was.” By stressing that parts blend, hijack the body, intrude flashbacks and images in order to get the attention and help of the normal life self, I can often spontaneously evoke empathy for the part: “Really?! You mean she only brought me so low because she wanted me to see how much pain she was in? Because she wanted help?!”

Connecting to the Resources of a Competent Adult

The easiest, most direct route to the normal life self is through those activities and life tasks or experiences with which this part is or was once identified. Is the client a parent? An administrator? Teacher? Attorney? Health care professional? Is there a hobby or cause that has meaning? If functioning has been problematic for an individual, we can ask: What “normal life” roles did he or she play earlier? Is there a wish or dream for a normal life that is important to the client? Does he or she play any role that requires prefrontal cortical activity? In using this model with young adults from inpatient and residential settings in a regional mental health system, we repeatedly described the normal life part to patients who, because of their abuse and neglect, had never functioned in normal life, even as children. Nonetheless, when our team from the Connecticut Department of Mental Health Young Adult Services described the Structural Dissociation model to these clients, almost all identified with having anormal life self: “That’s the part of me that wants out of this hospital!” “Yes, that’s the part that wants to be normal, not a mental patient.” “That’s the ‘me’ who wants to go to college and get a job.” “I recognize my normal life part: she’s the one who wants to get married, live in a real home, and have kids.” Others could begin to feel a more palpable connection to their normal life selves once they began to associate their symptoms with the different parts and could disidentify from them, that is, differentiate what “I” want from what the parts seemed to be seeking. Whatever past “normal life” experience or vision of a future a client may have, it can become the vehicle for developing a stronger felt sense of having an adult body and mind (Ogden et al., 2006). I have helped clients find a normal life part on inpatient units (the part that organized a ping-pong tournament for her peers), in activities such as jewelry-making, playing tennis, horseback riding, volunteer work with animals or children, even in serving as the voice of wisdom and support for others in their lives.

Each time I point out, “That’s your going on with normal life self—sticking with what’s important—putting one foot in front of the other no matter what,” I bring the client’s attention to the influence of the normal life self in their lives. When the client protests, “But that’s just a false self—I just fake it,” I challenge their curiosity: “So the belief is that your normal life self is just a fake—how interesting … But how could that be? Even if you are ‘faking it,’ it’s still you. If I faked it, I would do it differently.”

I underscore the courage and instinctive drive to seek normal even in an abnormal environment: “Think of it this way: the normal life self is the part of you that keeps trying to be OK even when all the other parts are freaking out, and that takes a lot of courage and determination—to ‘keep on keeping on’ when your parts are freaking out. A ‘false self’ wouldn’t have to work that hard!”

Selves-Acceptance

“Befriending” one’s parts is not simply a therapeutic intervention: it also contributes to developing the practice of self-acceptance, one part at a time. When clients pause their emotional reactivity to “befriend” themselves, to be curious and interested rather than dismissing or judgmental, they slow time. Autonomic arousal settles; there is a relaxing of the sense of urgency to do or be anything different. With their bodies in a calmer state, they can be more at peace, and, as a result, their parts feel more at peace. Self-alienation (i.e., disowning of some parts and identifying with others exclusively) does not contribute to a sense of peace or well-being, even when it is absolutely necessary in order to survive. Self-alienation creates tension, pits part against part, communicates a hostile environment (often much like the traumatic environment), and diminishes the self-esteem of every part.

As I made my case for accepting and welcoming her parts to a young graduate student, Gaby, she grew thoughtful. “These are good ideas. What about having a daily meditation circle?” she asked. “I could sit and invite them to join me in the circle. They wouldn’t have to talk, but if they wanted to tell me about things they were worried or upset about, they could. It would be a safe place for all of us.” The next week, she reported back. “It was amazing to see them all there—to know they came to meet me and to see if I would really listen. A lot of them were upset about how stressful my job is and the memories it brings back. I told them I’d talk to you about how to make it easier for them.” [See Appendix B, Meditation Circle for Parts.]

“Befriending our parts” means that we “radically accept” (Linehan, 1993) that we share our bodies and lives with “roommates” and that living well with ourselves requires living amicably and collaboratively with our all of our selves, not just the ones with whom we feel comfortable. As Gaby’s Meditation Circle taught her, the more we welcome rather than reject our owned and disowned selves, the safer our internal worlds will feel.

“I am not I.

I am this one

walking beside me whom I do not see,

whom at times I manage to visit,

and whom at other times I forget;

who remains calm and silent while I talk,

and forgives, gently, when I hate,

who walks where I am not,

who will remain standing when I die.”

(Juan Ramon Jimenez, 1967)

References

Creswell, J.D., Way, B.M., Eisenberger, N.I., & Lieberman, M.D. (2007). Neural correlates of dispositional mindfulness during affect labeling. Psychosomatic Medicine, 69, 560–565.

Gazzaniga, M. S. (1985). The social brain: discovering the networks of the mind. New York: Basic Books.

Hanson, R. (2014). Hardwiring happiness: the new brain science of contentment, calm, and confidence. New York: Harmony Publications.

Jimenez, J.R. (1967). I am not I. Lorca and Jimenez. R. Bly, Ed. Boston: Beacon Press.

Levine, P. (2015). Trauma and memory: brain and body in search of the living past. Berkeley, CA: North Atlantic Books.

Linehan, M. M. (1993). Cognitive-behavioral treatment of borderline personality disorder. New York: Guilford Press.

Meichenbaum, D. (2012). Roadmap to resilience: a guide for military, trauma victims and their families. Clearwater, FL: Institute Press.

Ogden, P. & Fisher, J. (2015). Sensorimotor Psychotherapy: interventions for trauma and attachment. New York: W.W. Norton.

Ogden, P., Minton, K., & Pain, C. (2006). Trauma and the body: a sensorimotor approach to psychotherapy. New York: W.W. Norton.

Phillips, M. & Frederick, C. (1995). Healing the divided self: clinical and Ericksonian hypnotherapy for post-traumatic and dissociative conditions: New York: W.W. Norton.

Santorelli, S. (2014). Practice: befriending self. Mindful, Feb. 2014.

Schwartz, R. (1995). Internal family systems therapy. New York: Guilford Press.

Schwartz, R. (2001). Introduction to the internal family systems model. Oak Park, IL: Trailheads Publications.

Shapiro, F. (2001). Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing: basic principles, protocols, and procedures, 2nd edition. New York: Guilford Press.

Siegel, D.J. (1999). The developing mind: toward a neurobiology of interpersonal experience. New York: Guilford Press.

Van der Hart, O., Nijenhuis, E.R.S., & Steele, K. (2006). The haunted self: structural dissociation and the treatment of chronic traumatization. New York: W.W. Norton.