There were ten separate campaigns developing in the early days of December, from one end of Finland to the other. To try to describe all of them in strict chronological order—recounting events on each front day by day—would be to create a most unwieldy and confusing narrative. Therefore, whereas the reader should bear in mind that all of these battles were evolving simultaneously, some sort of arbitrary order must be imposed for the sake of clarity. Since the threat to Finland was most critical on the Karelian Isthmus, and since the military operations there in December form a coherent narrative unit, that theater will be examined first. Subsequent chapters will work northward from Fourth Corps’s zone to the Arctic.

General Meretskov stormed across the Isthmus frontier with 120,000 men, 1,000 tanks, and the supporting fire of about 600 guns. Before the border area could be turned into a combat zone, however, the Finns had to move the civilians out. During the interval between the collapse of the Moscow negotiations and the start of hostilities, thousands of Karelian families were evacuated. The Finnish border troops who organized this exodus were deeply moved by the toughness and patriotism of the farming families they dealt with. They were simple people, few of them educated, and they lived poor, marginal lives close to the earth. But they had sisu in abundance.

In one village, a detachment of border guards came up to the home of an aged peasant woman and sadly informed her that she must prepare to leave her home, possibly forever, with only the belongings she could carry on her back and in the horse-drawn sled tethered near her cabin. In the morning, they would return and burn her house to the ground, so that the Russians could not sleep there. When the soldiers returned the next morning, they found the sled parked by the old woman’s door, piled high with her possessions. When they entered the farmhouse, they were startled to see that the entire dwelling had been scrubbed and whitewashed until it sparkled. Stuck to the wall by the door, the woman had left a note saying that she had gone to fetch something at a neighbor’s house and would return in time to drive the sled away in the soldiers’ company. In the meantime, the note concluded, if the soldiers would look by the stove, they would find enough matches, kindling, and petrol to burn the house quickly and efficiently. When the old woman returned, the soldiers asked her why she had gone to so much trouble. Pulling herself upright with all the dignity she could summon, she looked them in the eye and replied: “When one gives a gift to Finland, one desires that it should be like new.”1

In another border village, covering troops roused an old farmer from his sleep—a gentleman who had refused earlier evacuation—and informed him that there would probably be fighting here by morning. They had come to burn his house tonight, they said, because when the battle started, they would be too busy. Grumbling, the old peasant gathered his few personal belongings, hitched up his horse, and rode eastward. Later the next morning, even as the first sounds of skirmishing could be heard in the distance, the same Finnish border troops were astonished to discover that the old man had returned and was wandering amid the ruins of his former house, prodding the ashes with a tree branch and muttering to himself in the thick dialect of the Karelian Finns. Several soldiers went over to the old fellow and asked him what he was doing back here, especially with the fighting now in earshot. The farmer’s gnarled features twisted into a grim smile and he said: “This farm was burned down twice before on account of the goddamned Russians—once by my grandfather, and once by my father. I don’t reckon it’ll kill me to do it either, but I’ll be damned if I could drive away without first making sure you’d done a proper job of it.”

The abandoned villages were not hospitable even in ruins. Booby traps had been placed with such cunning and imagination that Pravda was moved to complain about the Finns’ “barbaric and filthy tricks.” Everything that moved seemed attached to a detonator; mines were left in haystacks, under outhouse seats, attached to cupboard doors and kitchen utensils, underneath dead chickens and abandoned sleds. The village wells were poisoned, or, if time and chemicals were lacking, fouled with horse manure. Liberal use was made of cheap pipe mines—steel tubes crammed with explosives, buried in snowdrifts and set off by trip wires; the charge went off at waist level and caused very nasty wounds. A colonel named Saloranta invented a type of wooden mine, impossible to detect with electronic devices, that was powerful enough to blow the treads off a tank. Soon the Russians had to detach patrols to clear the roads with sharp prods before the tanks could advance.

Under the newly frozen lakes, mines were strung on pull ropes; only partly filled with explosives so they would retain buoyancy for several days, the charges were not designed to blow up the tanks but rather to shatter the ice beneath them. When word got around about this tactic, the Russian tank drivers began to avoid the lakes altogether, which was precisely what the Finns wanted, since it was much easier to ambush the vehicles in the countryside than out on the lakes, where their guns could sweep the terrain all around. At several locations the Finns unrolled enormous sheets of cellophane over frozen lakes so that, from the air, they would look unfrozen, and the enemy would not even bother trying to cross them.

Almost from the opening minute of the war, traffic began to back up on the Russian side. Mechanized columns were jammed bumper to bumper, with vehicles slewing off the roads into the morass of snow, weeds, and half-frozen bogs on either side. Sporadic but heavy snowstorms lashed the advancing columns, immobilizing some and slowing others to a crawl. And even a token show of Finnish resistance caused delay and confusion far out of proportion to the size of the force doing the resisting.

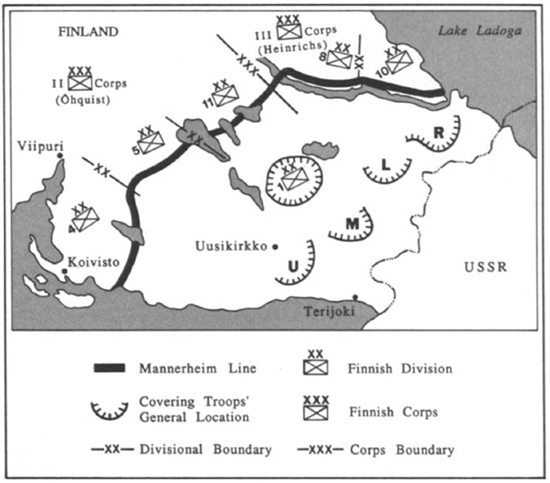

Between the frontier and the Mannerheim Line was a buffer zone between twelve and thirty miles deep. In this border area, Mannerheim had deployed about 21,000 men, organized into four “covering groups.” Each was designated by a letter of the alphabet corresponding to its commander’s name. Under control of Second Corps (Öhquist), were Groups U, M, and L; under control of Third Corps (Heinrichs) was the northernmost covering force, Group R. Strategic command of the overall Isthmus battle was under command of Mannerheim’s chief of staff, a tough-minded, intelligent general named Hugo Östermann. The general line along which the covering troops were positioned ran through a string of small Karelian villages: Uusikirkko, Kivinapa, Lipola, Kiviniemi. A large part of the First Division was held in reserve between the covering troops and the line, between Lakes Suulajärvi and Valkjärvi. Mannerheim wanted to disrupt and pin down at least one large Russian formation out in the open and then bring up the First Division to attack it, but things didn’t work out that way, and most of the division appears to have been withdrawn back into the line before it saw much action.

General Östermann had always thought the plan too ambitious for untried troops. More than Mannerheim, he seems to have appreciated the fact that the “wild card” in this strategy was the Russians’ tanks and the effect they might have on troops who had never faced armor before, even in training. Östermann had envisioned a strictly delaying role for the covering troops, while the Mannerheim Line was being manned. Of course, as it turned out, the line already was manned when the war began. Since this was the case, Östermann felt it was folly to risk good troops in front of good defensive positions rather than behind them. The net result of this command uncertainty was furious resistance at some places, token displays at others, and a spotty effort rather than a concerted defensive strategy in the buffer zone as a whole.

3. Actions of Covering Groups on Karelian Isthmus

By the end of the war’s first day, the Russians had pushed back elements of Group U to the eastern edge of Terijoki village. Finnish resistance was fierce, and about half the village was torched either as a result of shell fire or as part of a “scorched earth” effort. The covering troops hit the Russians with four counterattacks on the first night, causing considerable casualties and confusion. When the Finns finally yielded the field, early on December 1, they blew up a railroad bridge in the invaders’ faces and halted all mechanized pursuit for about ten hours.

Enough reports had come up the chain of command by the end of December 2 for Mannerheim’s generals to have a roughly accurate picture of the Russians’ advance. Clearly they were operating in such a way as to leave themselves vulnerable for the sort of quick-jab tactics Mannerheim had originally envisioned. Demolitions and booby traps—and the fear of booby traps, which was just as effective—were delaying the Reds’ advance. Token Finnish resistance, even a single sniper shot, had halted vast columns for hours. The enemy was sticking to the good roads, which caused its formations to bunch up and become harder to deploy. Under those conditions, the army was very vulnerable to flank attacks. Moreover, most of the Red columns were out of touch with each other. Columns that had crossed the border moving parallel to one another were now sometimes heading in divergent or even opposite directions, exposing one another’s flanks and rear more dangerously with each kilometer they advanced. Some tempting opportunities seemed to present themselves, but by the time Östermann got his plans drawn up, the situation had changed. Things would not hold still long enough for the Finns to take advantage of the enemy’s awkwardness.

It was mainly the tanks that were causing the confusion. No Finnish soldier had ever confronted a rolling wave of armor before, or, for that matter, even a single modern tank in a training scenario. Officers had briefed their men on the psychological effect of massed armor, trying to build them up for that particular experience, but talking about it in a training class and actually facing roaring, clanking, fire-belching steel monsters were two very different things. The Russians’ armored tactics, at this stage of the war, were pretty crude—straight-ahead cavalry charges, mostly—but their effect on the Finns was shattering.

At one sensitive juncture, two alarming reports reached Östermann’s headquarters stating that the enemy had gained a beachhead on the Baltic coast and that a major armored breakthrough had occurred just a few kilometers in front of the Summa sector of the Mannerheim Line. Both reports proved false, but by the time the truth was learned, it was too late to halt the withdrawals they had caused. A great deal of terrain was given up without a fight, and Mannerheim was furious.

He ordered Öhquist to turn his men around and retake the ground that had been lost. Öhquist had the backbone to refuse, and to assume personal responsibility for the consequences. He told Mannerheim that the lost ground was not worth the cost of recapturing. Öhquist had spoken to his field commanders, and they had all expressed resentment at the situation. Their men were tired, confused, and resentful that headquarters was sending them all over the Karelian Isthmus on half-cocked missions whose objectives seemed clear to no one. Mannerheim backed down.

Finnish historians have made a determined attempt to track down the origin of those two alarms, but without success. Most likely the disorganized state of Finnish communications was to blame, along with the confused nature of the fighting. Add to those factors the raw, inexperienced reflexes of midlevel staff officers, and the result was a situation that permitted a pair of wild, unverified rumors to penetrate all the way to Isthmus Headquarters disguised as fact. Any and all such rumors could, and in a more experienced army would, have been either squelched or verified at a local level before entering the chain of command. Those same chaotic conditions, of course, also made it easy for Finnish-speaking Red Army personnel to tap phone lines, break in on radio frequencies, and otherwise interpose themselves inside the fragile net of Finnish communications. The reports may have been simple ruses; if so, they were spectacularly successful, and the men who thought them up deserved the Order of Lenin, for each rumor had the effect of handing the Russians a sizable battlefield victory at no cost to themselves. Certain Finnish commentators, however, do not rule out the possibility of treason, although if any tangible evidence exists to substantiate that charge, it remains classified to this day.

On December 4 Mannerheim came storming down to Östermann’s headquarters at Imatra. Öhquist—who had plenty of better things to do—was ordered to attend. If we are to believe Östermann’s account, Mannerheim gave him a cruel dressing down, blaming the collapse of his cherished “forward zone” strategy on Östermann’s halfhearted compliance with orders. Östermann offered his resignation; according to Östermann, so did Mannerheim. Having vented their tensions, however, both men backed off from this angry confrontation, realizing what a deleterious effect such an occurrence would have on the Finns’ morale. Mannerheim still seemed to believe that some of his strategy could be salvaged.

And by December 4 there were signs that the Finnish Army was steadying down. After the initial shock had worn off, the Finnish soldiers began to figure out ways to handle the tank problem. It was soon discovered that the tanks could be dealt with at close range in a number of ways. Logs, even crowbars, jammed into their bogie wheels often stripped a tread and immobilized them. Once an attacker on foot got really close to a tank, the attacker had the advantage. The problem still remained, however, of surviving long enough to get that close.

By now, too, a cheap, effective, homemade weapon had appeared in great quantities. It was the “Molotov Cocktail.” The Finns did not invent these devices—that honor apparently goes to the Republicans in Spain—but they did christen them with the name that has stuck like glue ever since, and in the first week of the war the Finns manufactured vast quantities of them. When the supply of bottles ran short, the State Liquor Board in Helsinki rushed 40,000 empty fifth bottles to the front.

In its crudest form, the cocktail was no more than a bottle full of gasoline with a rag stuck in its mouth; but the puny fireball that resulted from this device was rarely enough to do more than scorch paint. The Finnish version was far more powerful, consisting of a blend of gasoline, kerosene, tar, and chloride of potassium, ignited not by a dishrag but by an ampoule of sulfuric acid taped to the bottle’s neck. Other, more potent versions included a tiny vial of nitroglycerine. Clusters of stick grenades, held together with tape, were also effective against treads. Twenty-pound satchel charges were used as well, although it took nerves of iron to get close enough to sling one of these weapons. Casualties among the tank-hunter squads were in fact very high—70 percent in some units—but there was never a shortage of volunteers. Eighty Russian tanks were destroyed in the border-zone fighting.

Heavy fighting continued in scattered locations on December 4, as some of the covering troops took positions in the Mannerheim Line. On December 5, part of the Fifth Division left the line and moved up to cover the left of Group U. The Fifth Division’s men were shaky, and none of them had faced tanks before. As they were moving into position, their advance element, a dismounted cavalry unit, suddenly began to scream “Tanks!” Panic ripped through the ranks. Whole companies took to their heels; men leaped out of trucks and left them with their engines running; gunners abandoned their weapons; wounded men were left on the field by their attendants. Most of the Fifth Division troops didn’t stop running until they were back in the line, where officers who had witnessed the debacle cursed and punched and in some cases threatened to shoot them. A few hours later, it was learned that the cause of the panic was a lone Finnish armored car that had been scouting in advance of the infantry.

Mannerheim’s display of pique seems to have lit a fire under Östermann because Finnish activity in the forward zone became much more aggressive on the night of December 5–6. A number of ambitious raids were launched against exposed Russian salients. A couple of these actions stung the Russians badly and inflicted several hundred casualties on them. By December 6, however, there really wasn’t much of a “forward zone” left: only a few shallow strips in front of parts of the Mannerheim Line. Virtually all of the still-committed covering troops had withdrawn back into the line by the end of the day.

If, on the one hand, there had been no smashing Finnish victory, at least there had been no Poland-style breakthroughs, either. And if many units had performed badly in their first encounters with tanks, most of them had rallied quickly and mastered their panic. If the Finns had possessed even a single brigade of modern armor, they could have cut several Soviet formations to ribbons; but tanks were costly items, and Finland’s military priorities were strictly defensive.

It is also possible, as some Finnish historians have suggested, that Mannerheim, old cavalryman that he was, had something of a blind spot about armor. He kept up with modern military theory, he knew all about the blitzkrieg, and he encouraged imaginative tactics for use against tanks. But tanks can also serve in a defensive capacity—as mobile reserves that can be used to add weight and power to local counterattacks, as artillery, as mobile antitank units. Given the constricted area of the Karelian Isthmus, the number of tanks needed was not prohibitively large; thirty or forty would have been a great help.2

Most important of all, however, by actively engaging the enemy from the first instead of passively waiting behind their fortifications, the Finns gained valuable experience. The most precious datum was the knowledge that the Russians were not supermen—far from it; they were slow, ponderous, unaggressive, and unimaginative. They could be beaten.

The Finns who had fought them in the border zone took that message back into the Mannerheim Line, and as they told their stories, there was a discernible stiffening of resolve along the entire defensive front. The defenders were going to need that resolve because there was a firestorm coming down on their heads like nothing any of them had ever imagined.

So congested and confused were the advancing Russian columns that it took an additional thirty-six to forty-eight hours after the covering troops had disengaged for the Soviet artillery to catch up and dig in. During those first days, a number of local probing attacks were sent against the line, but they were not seriously threatening.

The Russians were, in fact, curiously lethargic and followed a predictable workaday routine. Russian infantry, often riding in trucks, would arrive at their jumping-off points at first light and then move out, not very energetically, in the general direction of Finnish lines. Sometimes by simple weight of numbers they forced the Finns to withdraw from exposed or unsupported positions, but thereafter they did nothing to exploit these little victories. In the afternoon, when the light began to fail, the Russians would withdraw a kilometer or two to the east, dig in behind a wagon circle of tanks, parked with their headlights and machine guns facing out, and build huge campfires. The Finns would then creep forward and reoccupy their positions, usually without interference and often reaping the bonus of discarded Russian equipment or bits of thrown away paper that proved useful to the intelligence staff.

Mannerheim was still unsatisfied. He wanted the Finns to do more, to press forward under cover of darkness and attack the enemy while he was warming himself at his campfires. Most Finnish soldiers lacked either the confidence or the experience to try a night attack, at least at this stage of the fighting. Moreover, early December marks the beginning of the period of maximum winter darkness in these latitudes, and very few flare pistols, star shells, or searchlights had reached the line as yet. One cannot blame the Finnish officers for not wanting to risk shaky troops on nocturnal operations without such things.

The first major Russian blows did not fall on the “Viipuri Gateway” at Summa but, rather, on the extreme left flank of the Mannerheim Line, in what would come to be known as the Taipale sector, after the small Ladogan fishing village that anchored its right flank. Meretskov knew the Finns would expect him to hit Summa first, and the reasonable assumption was that the defenders had concentrated both their strongest fortifications and their tactical reserves in that part of the line. He therefore resolved to launch a strong feint attack at Taipale, in hopes of drawing off those reserves and softening up the Summa sector.

But the Finnish Tenth Division, dug in at Taipale, knew it could count on no significant reinforcements. Mannerheim and his generals knew exactly what Meretskov was up to, and they were not going to shift a single company from Summa if they could help it. The line at Taipale followed the outline of a long, tapering, blunt-ended promontory, bounded on the south by the Suvanto branch of the Vuoksi Waterway and on the north by Lake Ladoga itself. Between the wide Suvanto and the lake ran the narrow Taipale River.

Along the Suvanto sector the Finns enjoyed a slight advantage of elevation and had some dry ground to dig in. Across the base of the promontory, however, the water table was very close to the surface and the entrenchments there were little more than augmented drainage ditches. The narrow tip of the peninsula, called Koukunniemi, was no-man’s-land. The Finns had voluntarily given it up because it was low, marshy, and utterly barren of cover. This was a sensible step to take, for it enabled them to streamline their positions and concentrate their limited strength. They also hoped that, by leaving the cape undefended, they could tempt the Russians into attacking there in strength. The open tongue of land was a killing ground. Every millimeter of it had been ranged by Finnish artillery and a fire plan worked out to bring down destruction on any force that gained a foothold there.

4. Russian Attacks on Taipale Peninsula, December 1939

As soon as their first artillery batteries caught up with them, late on December 6, the Russians moved against Taipale. Their attack began with heavy artillery preparation, a foretaste of what was to come all along the line. After a four-hour bombardment, the Red infantry swarmed forward. They attempted a crossing at the Lossi ferry landing but were thrown back. Just as the Finns had hoped, the enemy did swarm on to the vacant promontory of Koukunniemi, and once they were in the bag, the Finnish artillery plastered that exposed ground with devastating effect. The Russians sustained hundreds of casualties, and the survivors of the barrage fled at the first sign of a counterattack by Finnish infantry.

Skirmishing and artillery duels now flared constantly along the entire Taipale sector as the Russians probed, tested the defenders’ strength, and brought up more guns. The next major Soviet effort against Taipale came on December 14, and by that date patrols and aerial photographs had given the Finns a clear idea of what sort of odds they faced. From December 6 to December 12, only one Russian division was engaged on this front; now a second division was deployed. Russian artillery strength had risen, during that same interval, to fifty-seven batteries, as opposed to the nine motley batteries the Finns could call on.

Under cover of predawn darkness on December 14, the Russians mounted a strong attack, preceded by a bombardment of unprecedented weight and fury. Crouching in their trenches under this thunderous flail, the men of the Tenth Division began to curse their own artillery, which fired not a shot in reply. The division was unaware that the Finnish gunners were under strict orders not to expend ammunition in counterbattery fire but to conserve their shells for more economical targets. They soon had plenty.

At about 11:30, the barrage suddenly lifted. The defenders looked to their front and saw thirty Red tanks rolling toward the southern end of Koukunniemi. Moments later another force of about twenty tanks was spotted advancing against the northern side. Behind the armor, in large, closely packed formations, was an entire infantry division. A nerve-grinding silence settled over the scene as the last shell fire tapered off. The stillness and tension were screwed to a terrible pitch by the growl and clank of the tanks’ treads, steadily increasing in volume. The infantry formations advanced with a steady, parade-ground gait. The tanks opened fire, their shells rippling across the neck of Koukunniemi. Casualties grew, and so did the Finnish infantry’s impatience with their own cannoneers.

Then with a startling crash all the Finnish guns opened up. Once again they had held fire until the enemy had reached a preplotted killing ground, and now their gunners fired with the methodical, steady rhythm of professionals—careful, unhurried salvos that dropped cluster after cluster of high explosive and shrapnel into the middle of those dense, screaming formations of Red infantry. The attack melted away in about five minutes, leaving the snow dotted with 300 or 400 casualties and the burning hulks of eighteen tanks.

A third Soviet division now entered the fight at Taipale, and the disparity of artillery strength grew even greater: nine Finnish batteries against eightyfour Russian. The newly arrived Red infantry performed poorly, however. They panicked under shell fire, and in attack after attack they were seen milling around under the bombardment like a herd of sheep. Nevertheless the attacks continued, establishing another trait that would prove characteristic of all the Mannerheim Line battles: the Russians’ willingness to take needless, hideous losses and still keep coming. Besides field and coast artillery, the Finns repulsed them with massed rifle fire and hundreds of machine guns and automatic rifles, with mortars and mine fields, and with grenades. Whole platoons of Russian infantry would become entangled in barbed wire hidden beneath snowbanks, like bugs in a spider web, and would be picked off one by one. Perhaps the deadliest weapons in the Finnish arsenal were the six-inch coast-defense rifles at Kaarnanjoki and Jariseva, which subjected the advancing Russian columns to airbursts of shrapnel, scything them down like giant shotgun blasts. One typical Russian attack during this period, lasting just under an hour, left 1,000 dead and twenty-seven burning tanks strewn on the ice.

Just before Christmas, the three Russian divisions operating in front of Taipale, the Forty-ninth, 150th, and 142d, were joined by yet another, the Fourth, on the eastern side of the Suvanto. Finnish reconnaissance planes revealed that the ratio of artillery was now nine batteries against 111. On Christmas Day, under cover of a thick ground fog, the Russians crossed the frozen waterway and established beachheads at Patoniemi and Pähkemikkö. When daylight burned off the fog, the Finns counterattacked furiously, killing 500 Russians at Patoniemi alone. The attacking force that had crossed at Pähkemikkö was betrayed by the very same fog that gave it cover. Unknowingly, the Russians had established their beachhead on a piece of terrain that was exposed to several flanking Finnish machine-gun nests, some of them only 100 meters away. When the mist evaporated, the Finnish gunners were surprised to see an unprotected swarm of enemy troops right in their sights. Eyewitness accounts of the battle state that the piles of Russian dead grew visibly larger each time the machine guns sprayed fire back and forth over the exposed landing spot.

Farther north along the Suvanto, another Russian battalion had taken advantage of the fog and established itself at Kelja. This unit dug in and signaled for reinforcements. If reinforcements had been able to cross in strength before the fog burned off, it is possible the Russians could have cut off the entire Taipale promontory. They were well behind the Finnish right and close to some lateral roads that would have facilitated such a move.

But by the time reinforcements began edging out onto the ice, the mist was lifting. Several machine guns and two old quick-firing field guns, probably “French 75s” from World War I, took the crossing under heavy fire. This checked the Russian buildup for a precious interval of time but obviously could not hold it permanently. Pressure was building and the danger was grave. Every Finnish gun that could be brought to bear was swung around to fire on the Kelja salient, and every available man, including headquarters’ and other noncombatant personnel, was organized to storm the beachhead after the guns finished working it over.

The battle seesawed all day and into the night, when the fighting continued under the hard white glow of a winter moon. At the same time the Finns tried to wrest Kelja from the Russians who were dug in there, they also had to repel repeated attempts by fresh forces of regimental size to cross the ice and reinforce the beachhead. The last Soviet troops were ejected from Kelja only at 9:15 the following morning, almost twenty-four hours after their initial crossing. It had been close and bloody work. Within the Kelja perimeter, and scattered over the ice leading to it, lay more than 2,000 Russian dead.

By mid-December the main weight of the Russian attack had shifted to the Summa sector; the Christmas crossings were the last massive effort aimed at Taipale. Even so, this never became a “quiet” sector. There were numerous Russian probes between January 1 and the start of the Russians’ all-out offensive in February, when the tempo picked up considerably. The Finnish Tenth Division held its line for the entire duration of the war, however, even though the same exhausted men manned these positions, without relief, during every single day of that ordeal. In December alone the Tenth suffered 2,250 casualties, and by the end of the war it was stretched very thin indeed.

Taipale was a slaughterhouse for the Russians. The land surrounding the promontory was either flat or lightly rolling, with few trees. The last half kilometer of any approach to Finnish lines had to be made across wide sheets of open ice. The Russian attacks formed in the open, approached in the open, and were pressed home in the open, against an entrenched defender well supplied with machine guns. Moreover, at this stage of the war, the Russians had no snowsuit camouflage for their men and no whitewash for their tanks. The tanks moved in ungainly clumps, and the infantry attacked in dense, human wave formations. It was the Somme in miniature. To the Finns who witnessed these attacks, it seemed beyond belief that any army, no matter how fatalistic its ideology or inexhaustible its supply of manpower, would continue to mount attack after attack across such billiard-table terrain.

In some battles the Finnish machine gunners held their fire until the range was down to fifty meters; the butchery was dreadful. In a number of cases Finnish machine gunners had to be evacuated due to stress. They had become emotionally unstable from having to perform such mindless slaughter, day after day.

Manning the center of the Mannerheim Line, in the Summa sector, was the Finnish Fifth Division. Except for a small number of men who had been involved in the last hectic stages of the border-zone fighting, its troops were untried. Before the Russian assaults began, the division’s commander went on record to express his own lack of confidence in his men’s ability to withstand a massive armored onslaught, or to plug Russian breakthroughs with counterattacks of their own.

The first big Soviet push against the Summa sector came at 10:00 A.M. on December 17, after a five-hour artillery barrage and tactical strikes by approximately 200 aircraft. There were two major thrusts: one against Summa itself and one against the Lähde road defenses, about two kilometers northeast of Summa village. The village of Lähde was situated several kilometers behind the line itself and was the site of a vital road junction. It was here, between these two tiny villages, that the Russians would push the hardest and here that the Mannerheim Line would finally break. But not this time.

Russian sappers led off the attack. They had crept close to the antitank rocks under cover of their own barrage, and when the shell fire lifted, they set off enormous charges that opened rubbled paths through the rocks and wire entanglements. Out of the smoke came a wedge of fifty tanks. These advanced to the gaps, crawled through and over the broken monoliths, crushed the wire, and thrust into the trench network held by the Finnish infantry.

To counter this tactic, the Finns had ordered their infantry not to withdraw but to stay in position and fight off the Red infantry that came after the tanks, in the hope that, unsupported, the tanks would eventually withdraw. It was a fairly desperate stratagem, and costly, but it worked. The Finns took galling fire from the milling Soviet tanks, but as long as they stayed put and cut down the infantry, no really dangerous breakthroughs occurred.

It would not have worked if Soviet tank/infantry tactics had not been such a botch. Coordination between the two arms was virtually nil: they attacked together, in the same general direction, but that was all. The tanks would surge forward, seize a patch of ground, and then churn around aimlessly on that ground, waiting for the infantry to catch up to them. When the tankers realized their infantry were not coming, whether because they had been repulsed at the wire or just never showed up at all, they either withdrew on their own accord or else formed defensive wagon-train circles and tried to hold their gains through the hours of darkness. And when the sun went down, the Finnish tank-killer teams came out to stalk.

Nailing tanks at close range was always dangerous, but it was especially so in the Lähde sector, where the trees were thin and the ground relatively flat. As always, there were too few Bofors guns, and the open landscape did not favor their deployment. Casualties among the antitank gunners were high.

To the south, on the same day, a similar attack was launched at Summa itself. Here either the Russian commander did not use sappers or they were knocked out by their own barrage, for relatively little damage was done to the antitank rocks. And if they did not actually stop the charging tanks, the rocks did force them to climb at a steep angle, rendering them momentarily vulnerable. Soviet designers had sacrificed all-around armor protection in their vehicles in favor of heavier firepower: below the turrets each type of Russian tank had its weak spots, which the Finns quickly learned to aim for. When a tank nosed up to climb over the rows of boulders, daring individuals could scuttle forward and slide mines on to the spot where the treads would soon come crunching to earth; and they could do it in relative safety, since the target tank and most of its neighbors would be unable to depress their machine guns low enough to hit the ground immediately around them.

In the Summa attacks the Russians tried to use the thick surface ice of the lakes as avenues of approach to Finnish lines. From the Russian side, the tactic seemed logical; there was plenty of room for a dozen or more tanks at a time to deploy and to advance swiftly across those surfaces. But if the middle of the lakes gave plenty of maneuvering room, the Finnish side did not; there, the rough shoreline terrain would close in again and offer, at most, four or five exits off of the lake that were suitable for tanks. And of course the Finns had covered those exits with ambush parties or antitank guns. In the first attacks against Summa and Lähde, the Russians lost thirty-five tanks, about one-third of the number engaged.

During that same twenty-four-hour period, the Finnish high command knew next to nothing about what was happening in the Summa sector. Russian shell fire had cut most of the telephone lines, and before the battle was an hour old, the Finns’ old-fashioned radio sets broke down, one by one, from exposure, concussion, and overwork. Even worse, frontline communications on the company and battalion level were a hodgepodge of improvisation. Many of the radio and switchboard operators had not been given codes to use, and it was obvious, early in the fighting, that the Russians were eavesdropping. So the frontline signalmen improvised, in classic Finnish style. They began to converse in a slang-riddled mixture of Swedish and regional Finnish dialect and started referring to friendly commanders by picturesque and frequently scatological nicknames. One pities the Russian interpreters who, with commissars observing closely, strove to make something rational of those conversations.

An even heavier blow was aimed at the Lähde positions on December 18, when sixty-eight tanks attacked behind heavy artillery and aerial preparation. The Finnish artillery, firing from their pinpoint prewar maps, destroyed ten vehicles before they could get within a mile of the line, taking the steam out of the attack. Another fifteen tanks were disabled in close combat. The Russian infantry never got through the boulders. At Summa an unsupported Russian infantry attack failed, leaving 500 bodies on the fields in front of the Finnish wire.

On December 19 the Summa positions were battered by continuous attacks. Heavy pressure was also felt east of Summa, along all the line defenses up to Lake Muolaanjärvi, where the monstrous heavy K. V. tanks appeared for the first time in the line fighting. Combat spread into Summa village itself. As the tanks churned through the narrow, rutted streets, Finnish infantry swarmed over them from roofs and upper stories, firing their Suomis through observation slits, levering open hatches and stuffing grenades into turrets, drenching the tanks with showers of Molotov Cocktails. By the time combat ebbed, on December 20, a huge tract of land in and around Summa was littered with the hulks of fifty-eight burned-out Russian tanks. So far, in the first twenty days of fighting on the Isthmus the invader had lost a minimum of 250 armored vehicles. One Russian tank brigade commander deserted to the Finns rather than face the consequences of reporting his losses to the division commissar.

At Lähde, on December 19, the critical “Poppius” bunker, a major fortification named for its commander, was hit so badly by close-range tank fire that its metal embrasures jammed. Overrun, its garrison resisted Russian infantry for forty-eight hours with grenades and small arms, until a Finnish counterattack retook the ground around the bunker and freed them.

Although there were some new attacks on December 20, they were not as serious as the earlier wave; the Russians had burned up their supplies as well as lost a substantial percentage of their armor. One tank battalion ran out of gas in front of Summa and just sat there, being picked off tank by tank. Twenty Russian vehicles penetrated Summa village on the twentieth, but eight of them, including three K. V. monsters, were knocked out in close combat.

The first Russian offensive against the Mannerheim Line had failed. Seven infantry divisions had been launched against Taipale and Summa, with two armored brigades and large packets of divisional armor, the whole effort supported by at least 500 guns and between 800 and 1,000 aircraft. Every Soviet unit thrown against the line had been mauled. Three-fifths of the tanks sent against the line had been destroyed. The tank drivers faced a layered defense: first, the ditches, bogs, and snow-covered mush of the landscape itself, augmented by extensive mine fields and tank traps; next, deadly accurate Finnish artillery fire; up close, rows of granite boulders, log obstacles, and camouflaged pits. Once they had gotten past all of those dangers and were inside Finnish lines, they faced gasoline bombs, satchel charges, cluster grenades, and individual Finnish madmen erupting out of nowhere to fire their rifles and submachine guns at observation slits, periscopes, and gun muzzles. If they survived all that and plunged through to the rear of the line, that was where the Finns had carefully sited their precious Bofors guns.

As for the long-suffering Russian infantry, they attacked with what Mannerheim described as “a fatalism incomprehensible to a European.”3 Their assaults had been delivered by waves or dense columns of men whose approach to Finnish lines had been screened, if at all, only by the incidental cover of scattered trees or the haphazard shield of the tanks—and these were usually too far ahead to protect the infantry at all. In one sector of the Summa battlefield, repeated attacks were delivered straight across a massive Finnish mine field by men who used their own bodies to clear the mines: they linked arms, formed close-order rows, and marched stoically into the mines, singing party war songs and continuing to advance with the same steady, suicidal rhythm even as the mines began to explode, ripping holes in their ranks and showering the marchers with feet, legs, and intestines.

A survivor of one such Russian attack recorded his experiences this way:

The battalion commander, Popov, called all the officers together and gave us the following orders:

“The attack will be repeated! And let’s not lie in the snow, dreaming of our warm beds! The village must be taken! Company commanders … will shoot anyone who falls back or turns around!”

One does not have to be a psychologist to know that the new attack, in which the soldiers would have to climb over the bodies of their own killed and wounded, would fail.

Of the more than 100 men of my company who went into the first attack, only 38 returned after the second one had failed. All of us worried and wondered: what happens now? As if in answer to our question, the battalion commander, who had taken over when Popov was wounded, called all the officers to him. … he held a field telephone in his hand. … “Comrades, our attack was unsuccessful; the division commander has just given me the order personally—in seven minutes, we attack again. …”

The rest I remember through a fog. One of the wounded, among whom we advanced, grabbed my leg and I pushed him away. When I noticed I was ahead of my men, I lay down in the snow and waited for the line to catch up to me. There was no fear, only a dull apathy and indifference to impending doom pushed us ahead. This time, the Finns let us approach to within 100 feet of their positions before opening fire. …4

From a letter found on the Summa battlefield after the first round of attacks: “We march already two days without food. … in the severe cold we have many sick and wounded. Our commanders must have difficulty justifying our being here. … we are black like chimney sweeps from dirt and completely tired out. The soldiers are again full of lice. Health is bad. Many soldiers have pneumonia. They promise that the combat will be over by Stalin’s birthday, the 21st of December, but who will believe it?”5

The strain on the defenders was almost as great. The Finns had to rebuild their defenses, string barbed wire, lay mines, and bury telephone cables at night when they should have been resting. Food was sporadic and poor. Thirst was worse; it was impossible to simply reach down and suck on a handful of snow because the shelling had contaminated the white stuff, and men who drank it suffered agonizing stomach cramps.

It had been a resounding defensive victory, but the more thoughtful Finnish officers looked beyond it and wondered what would have happened if the Russians had handled their armor professionally. Their defeat had been so smashing and one sided that it seemed reasonable to assume that the Russians, too, would ask that very question and, next time, do things better.

1Langdon-Davies, 126.

2Mannerheim may have learned a lesson from the Winter War, however, because when the Finnish Army went into action again, in 1941, it had lots of tanks, most of them, in fact, reconditioned Russian vehicles captured in 1939–40. They were augmented by some Czech models handed down by the Wehrmacht.

3Mannerheim, 368.

4Garthoff, Raymond I., ed., Soviet Military Doctrine (Glencoe, Ill.: Rand Corporation, 1953), 237.

5Engle, Eloise, and Lauri Paananen, The Winter War (New York: Scribner’s, 1973), 63.