No battle of the Winter War captured the public’s imagination like the Battle of Suomussalmi. The campaign continues to be taught in military academies as a “classic,” an example of what motivated, well-led troops can do, with innovative tactics, against even a much larger adversary.

Suomussalmi was a provincial town of 4,000 inhabitants, made up mostly of loggers and hunters, although there was good seasonal fishing in the long, narrow, twisty lakes that radiated out from the road junction where the town had grown up. As was true with the other Soviet thrusts into the central and northern wilderness, the Finns were startled that the enemy would even bother to attack here and flabbergasted when Stalin committed two entire divisions to the operation: the 163d and Forty-fourth.

Under the command of Major General Zelentsov, the 163d Division moved from its base at Uhkta, on the Murmansk Railroad, along one of those top secret forest roads that made it possible for Stalin to mount the forest offensives. The Russians’ objective was to knife through the wilderness and capture Oulu, the major rail connection with Sweden, and effectively cut Finland in two at the “waist.” There were two roads leading to Suomussalmi from the frontier: The northern one, called the Juntusranta road after the first Finnish settlement inside the border, ran southwest, then joined a major north-south artery that led through Suomussalmi to Hyrynsalmi in the south and Peranka to the north. The southern track, called the Raate road, intersected the Peranka-Hyrynsalmi road in the middle of Suomussalmi and then meandered toward the more populous interior of the country. The southern route was a much better road, and if the Russians were going to try anything in this sector, the Finns expected them to use it.

Zelentsov put two of his three regiments across the border, however, on the Juntusranta track, enabling him to enjoy complete tactical surprise and massively one-sided weight of numbers. To oppose his crossing, the Finns initially deployed a border guard company of fifty men. Brushing aside the delaying actions of the border troops, the two Soviet regiments pressed on and reached the Palovaara junction sometime during the night of December 5–6. Meanwhile, their sister regiment was rolling into Suomussalmi itself, via the Raate road. Resistance on the Raate road had initially been feeble: two platoons’ worth of border guards and a couple of improvised roadblocks. Even so, the invading Soviet regiment only made six miles in the first twenty-four hours of the war. Finnish reserve companies were hastily rushed down from Kajaani, and these served to stiffen the defense and slow the invaders’ progress. By the morning of December 7 the inhabitants of Suomussalmi had been completely evacuated and most of its buildings put to the torch. It was a hasty job, however, and not all the fires caught. Enough dwellings were left to shelter a few hundred men and to present the counterattacking Finns with some street-fighting problems in the days to come.

Of the two Soviet regiments that had come in by the northern road, one turned north at the Peranka road junction and advanced toward Lake Piispajärvi; the other turned south and headed for Suomussalmi itself. Late on December 7 it linked up there with the regiment that had come in on the Raate road.

By companies and battalions, Finnish reinforcements began hurriedly to converge on this remote location. The enemy thrust along the Juntusranta road appeared to Major General Tuompo to pose the more significant threat, so he dispatched his meager forces to that sector first. Independent Battalion ErP-16 began arriving in Peranka at 1:00 A.M. on December 6. By midday the entire battalion had spread out on good defensive ground near Lake Piispajärvi. No sooner had the Finns taken position than elements of the Soviet 662d Regiment, which had been ordered to take Peranka by nightfall, began probing attacks. After twenty-four hours of vigorous skirmishing the initiative passed to the Finns, outnumbered though they were.

All Finnish forces operating above the Palovaara road junction were now grouped under the designation “Task Force Susi,” under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Paavo Susitaival, a reserve officer who had just been granted leave of absence from his position as a member of Parliament. Susitaival’s force was able to contain the Russians with surprising ease, due partly to the fact that Zelentsov, making the first of several costly mistakes, had stripped the 662d Regiment of one of its battalions, retaining it as his divisional reserve. Task Force Susi therefore found itself engaging only about 2,000 enemy soldiers. Nor was the 662d in good shape in other ways: its commander, Sharov by name, had sent a message of complaint on December 11, promptly deciphered by Finnish radio intelligence, bitterly lamenting that his men lacked boots, snowsuits, and sufficient rations. From other radio intercepts the Finns soon learned that one of the divisional Politruks had been “fragged” by some of his men. Another transmission, decoded on December 13, spoke of forty-eight frostbite cases and 160 battle casualties in the 662d alone—10 percent of Sharov’s force, and he had done nothing more than skirmish with the Finns so far. Clearly this was not an elite formation.

Paradoxically for such a technologically primitive army, Finnish radio intelligence was highly developed and would prove invaluable during the Suomussalmi campaign. Mobile vans prowled the back roads, eavesdropping on Russian radio traffic and feeding the signals to data-collection centers where cryptanalysis was speedily performed. Local commanders usually had decoded enemy radio signals in their hands only four hours after they had originally been sent; a slow pace, perhaps, by the standards of today, but by the standards of 1939 a very smart performance indeed, and one that greatly aided the Finns in making their tactical decisions.

On December 14 and 15 Sharov tried to regain the initiative and was able to score a temporary advance from Haapavaara to Ketola, where he was stopped cold by heavy mortar and Maxim fire. The Finns once again employed their heavy machine guns in the role of light artillery. Sharov’s lead battalion took 150 casualties. With 20 percent of his regiment out of action from fire or frostbite and the rest of his men rapidly approaching the limit of their physical strength, Sharov and his remaining troops went over, permanently as it turned out, to the defensive.

Meanwhile a much more serious threat was developing from the stronger, southern arm of the Russian offensive. With two of the 163d Division’s regiments and most of its heavy weapons and armor concentrated close to Suomussalmi village, it seemed clear to the Finns that the main push would probably be in the direction of the road junction at Hyrynsalmi. An otherwise insignificant logging town, Hyrynsalmi offered the region’s best road connection to Puolanka, an important stepping-stone on the route to Oulu, and was also the terminus of the sector’s only railroad line. It was vital for the Finns to retain control of the place.

A major reinforcement was now on its way, in the form of a single man, an officer who would galvanize the Suomussalmi defenders in much the same way as Talvela had done at Tolvajärvi. On the same day the Russians linked up at Suomussalmi village, December 7, Mannerheim ordered JR-27, the only remaining uncommitted regiment of the Ninth Division, to entrain for the new crisis spot. The commander of JR-27, Colonel Hjalmar Siilasvuo, was yet another veteran of the fabled World War I Jaeger Battalion. The son of a newspaper editor, Siilasvuo was in peacetime a lawyer. A short, blond, blunt-speaking man, he was about to prove himself one of Finland’s greatest tacticians.

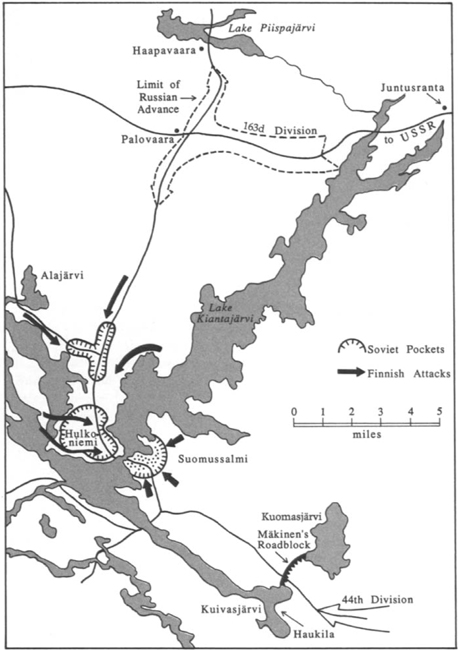

9. Suomussalmi Campaign: Destruction of Soviet 163d Division

Siilasvuo reported to General Tuompo, in Kajaani, and was informed of the organizational steps being taken to counter the unexpected threat at Suomussalmi. His regiment, JR-27, was now the nucleus of an ad hoc brigade-strength task force whose mission was to destroy the 163d Division—not just stop it but destroy it. That was a tall order, since the enemy, in addition to being numerically superior, was plentifully supplied with tanks and artillery. JR-27, by contrast, had no heavy weapons at all, not even as yet a single antitank gun, and was still without its full inventory of such basic items as tents and snowsuits.

What JR-27 did have was plenty of skis and men who knew how to use them. Most of the regiment’s rank and file were from small forest towns like Suomussalmi. A fair number of them were loggers. They knew the forest, they knew how to ski cross-country, and there was already more than a foot of snow on the ground. If Siilasvuo did not have firepower going for him, he had the next best thing: mobility.

That particular advantage came into play from the first day of JR-27’s deployment. Siilasvuo set up his headquarters in the home of a forester in Hyrynsalmi village. The Russians apparently did not know that the railroad extended as far as Hyrynsalmi—it was new track—enabling the Finns to concentrate their reinforcements only twenty-five miles south of Suomussalmi. Siilasvuo was therefore able to block the enemy thrust with more than a battalion, less than twenty-four hours after receiving his orders. When the Russians advanced on Hyrynsalmi on December 9, they were surprised to find themselves pinned down by heavy, accurate machine-gun fire only a kilometer or two from their starting point.

By the end of December 10 Siilasvuo was already planning a counterattack. All of JR-27’s battalions were available, in addition to two battalions’ worth of covering troops who had been fighting in the area since November 30. The condition of those covering troops gave Siilasvuo some anxiety. They had been fighting, and mostly retreating, for two weeks without respite, and just prior to Siilasvuo’s arrival one of the company commanders had committed suicide. Siilasvuo permitted the rumor to circulate that he represented the first element of an entire division. In a sense this turned out to be true; Mannerheim designated Siilasvuo’s command as the “Ninth Division” on December 22, a logical thing to do since the original Ninth Division had now been deployed piecemeal, and nothing remained of it except a skeletal cadre of administrative officers in Oulu. For the moment, however, Siilasvuo did not know that was happening, so his claim was quite an exaggeration. But its effect on the covering troops’ morale was bracing and far-reaching. No longer did they feel abandoned to their fate, or that their enormous exertions had been for nothing. In the days to come they would give a good account of themselves.

Siilasvuo thought he could deal with the Soviet 163d Division. Its commander, Zelentsov, had showed himself to be neither very aggressive nor very imaginative. His northernmost regiment, up near Piispajärvi, had become entirely passive, and the division as a whole lay stretched out in a vulnerable road-bound column almost twenty-five miles long, from Piispajärvi all the way back to a point east of Suomussalmi village. Before dealing with the 163d, however, Siilasvuo wanted to make sure it was truly “in the bag,” so he launched a road-cutting operation whose ultimate goal was to seal off the Raate road against any reinforcements coming across the Soviet border.

On the night of December 10–11 Siilasvuo moved the bulk of JR-27 to an assembly area southeast of Suomussalmi, about five miles below the Raate road. He also put his engineers to work laying down an “ice road” network that would further increase his mobility, enabling the Finns to hustle their few pieces of artillery from point to point, unlimber and fire a few rounds, pack up again, and vanish into the wilderness, all so quickly that the enemy rarely had time to reply.

The attack Siilasvuo launched on the morning of December 12 would be the first of numerous road-cutting operations his men would conduct in this sector. A typical such attack went like this: The combat team selected to make the actual cut would move into preselected assembly areas just beyond reach of the enemy’s reconnaissance patrols. Finnish patrols, meanwhile, had already established the most concealed routes of approach to the road from the assembly area and secured them by positioning pickets of ski troopers on the flanks. Each combat team made its approach according to a timetable that allowed the commander on the spot to gauge the pace so that his men would not arrive at their jumping-off point too tired to do the job. At the final assembly point, usually within earshot of the road, heavy winter garb was discarded and left under guard along with the other heavy equipment. The assault teams wore only lightweight snowsheets and carried as much firepower as possible: Suomis, Lugers, grenades, and satchel charges.

Speed and shock were the ingredients of a successful road-cutting attack. While the assault team was deploying, scouts would creep as close as possible to the point of impact and would bring back last-minute coordinates for the mortars and Maxim guns, which would put down suppressive fire on either side of the raiding party.

At the signal, a short, sharp barrage of mortar and machine-gun fire would crash into the intended point of contact. After a few moments, the supporting fire would be shifted 100 meters or so to the right and left of that point, in effect sealing off a narrow corridor across the road. That was the moment to launch the assault.

A flurry of half-invisible men would erupt from the forest incredibly close to the Russians, grenading everything in front of them, raking the nearest foxholes, trucks, and tents with Suomi fire. Demolition teams would peel off and race parallel to the road, hurling their explosive packs into vehicles, open tank hatches, field kitchens, and mortar pits, with each team accompanied by a few sharpshooters who were under orders to kill the officers first. It was at this stage of the operation that enemy resistance was most fierce, as desperate Soviet troops leaped from their vehicles onto the skiers’ backs, or came up out of their holes to meet them with bayonets, pistols, or rifle butts. To men watching the operation from the woods on the Finnish side, it often appeared as though the roadway were convulsed by spasms of flame and smoke with khaki and bedsheet-white figures knotted together.

The main purpose of the raid was not to wipe out every Russian soldier along a given piece of the Raate road. It was to sever the column by overwhelming localized impact and knife through to the woods on the other side. Once a breach had been torn in the Soviet column, no matter how narrow, fresh reserves would swarm out of the forest to consolidate and widen the gap, including combat engineers who would immediately, under fire, start fortifying the sides of the original breach. Eventually, in the motti operations to come, each road-cut was 300 to 440 meters wide, with strong barricades and earthworks sealing it off at both ends. The ramparts were often made stronger by incorporating overturned Soviet trucks or captured pieces of armor, some of them with their guns and turret mechanisms still operable. Siilasvuo and his men became virtuosos of this road-cutting technique, and on their best days they could mount two or three such operations simultaneously at widely separated points along the road, making it almost impossible for the Russians to mount an effective defense.

For his first road-cutting attack, and as the site of his vital roadblock to the east, Siilasvuo chose a natural choke point near the easternmost end of the 163d’s column, a mile-wide isthmus between Lakes Kuivasjärvi and Kuomasjärvi. The task of setting up the roadblock was given to two companies of JR-27 under Captain J. A. Mäkinen. Siilasvuo may already have had inklings, thanks to the Finns’ radio intelligence system, that a new Soviet division was forming up across the border to come to the aid of Zelentsov’s stalled offensive. With the roadblock in place, he figured that division would do only two things: either dig in and try to bulldoze its way through the roadblock, which he estimated would take them several days to do, or else try to outflank the roadblock. But because Siilasvuo had chosen ground that was flanked on both sides by wide-open frozen lakes, any Russian commander who tried to outflank the roadblock would incur very heavy casualties from Mäkinen’s numerous machine guns. Of course a really deep flanking movement, a wide end run through the deep forest, would easily nullify the roadblock, but Siilasvuo was gambling that the enemy would not do that. The Russians would have to abandon all their heavy equipment and overcome their demonstrated fear of the deep woods. As it happened, Siilasvuo was right. The gamble worked and permitted Mäkinen and 350 men to close the road to an entire reinforced Soviet division.

While the roadblock operation was successfully developing, Siilasvuo launched a battalion-sized probe against Russian positions west of the village near Hulkoniemi. This met with only limited success; the defenders were too well entrenched and too heavily supported by artillery for a single battalion to make headway against them. At least the Finns were now able to bring that section of road under harassing fire, virtually isolating Suomussalmi from that direction.

Methodically Siilasvuo tightened the noose on Suomussalmi, launching numerous quick, sharp raids against the road leading north from Hulkoniemi and against the western outskirts of the village itself. In one such skirmish two Red tanks attacked a Finnish squad caught in lightly wooded terrain near the village. A lieutenant named Huovinen taped five stick grenades together and crawled toward the tanks; his friend, First Lieutenant Virkki, intended to provide covering fire, despite the fact that he was carrying only his side arm. At a range of forty meters Virkki stood up and emptied his 9 mm. Lahti automatic at the vehicles’ observation slits. The T-28s replied with a spray of machine-gun fire, and Virkki went down. Those watching felt sure he had been killed. But he had only dropped down to slap another magazine into the butt of his weapon. That done, he jumped up and once more emptied his pistol at the tanks. Altogether this deadly dance step was repeated three times, at which point the Russian tankers seemed to become unnerved. They turned around and clanked back to the village. Meanwhile, Lieutenant Huovinen had been crawling closer to them from the rear and now had his arm cocked to throw the grenade bundle. Just at that moment the tank nearest him put on speed and retreated. He lowered his grenades in astonishment. Surely there were not many instances in modern warfare of tanks being repulsed by pistol fire.

Finnish officers were trained to lead from the front, and a great many of them died at Suomussalmi. A day or two after Virkki had driven off three tanks with a handgun another lieutenant named Remes took a Russian bullet in the hand. He turned over his command, deprecated the seriousness of his injury with a few jaunty remarks to his men, and went off on his own to find an aid station. He never arrived. Just before dark the following day his body was found in the deep woods, where he had apparently run into an enemy patrol. Around him lay six dead Russians.

On December 16 Siilasvuo received his first artillery support, a four-gun battery of 76.2 mm. weapons dating from before the Russo-Japanese War, followed forty-eight hours later by a second, more modern battery, and four days after that by a pair of urgently needed Bofors antitank guns. On December 22 Siilasvuo learned that he was now officially in command of a division rather than a task force. Mannerheim sent him a Christmas present in the form of infantry regiment JR-64, a newly organized battalion of ski guerillas designated “P-1,” and one additional independent battalion of infantry. With a total of 11,500 men, Siilasvuo was now as strong as he was likely to get.

Task Force Susi, still containing the enemy up in the direction of Peranka, also received a welcome reinforcement in the form of bicycle battalion PPP-6, which was given the task of clearing out some Russian cavalrymen who were operating along a primitive road that ran between Lakes Alajärvi and Kovajärvi a couple of miles northwest of Suomussalmi village. This they did successfully in a series of firefights that raged from December 17 to December 22, by which time the battalion had moved out of Task Force Susi’s zone and was brought under Siilasvuo’s direct command. This unit would provide much-needed extra punch on the northern end of Siilasvuo’s sector.

At about the same time PPP-6 was clearing its piece of road, the main force of Task Force Susi, ErP-16, sent about two-thirds of its men on skis on a wide flanking march to Tervavaara. From there successful raids were launched on Russian positions near the Palovaara road junction. The noose was tightening.

On December 23 Task Force Susi received a sizable reinforcement, Mannerheim having decided it was time to redouble his bets in this theater, in the form of regiment JR-65, a newly formed unit that had ridden all the way from Oulu, more than 100 miles, aboard trucks in twenty-five-below-zero weather. Positioned first on the north shore of Lake Piispajärvi, JR-65 rolled the enemy back as far as Haapavaara by Christmas. The effect of this action was to pin what was left of the Russian 662d Regiment firmly in place. Sharov was unable to send so much as a squad to reinforce the more important sector near Suomussalmi itself. His unit’s powers of resistance were in fact rapidly waning, as Colonel Susitaival learned on December 27, when his task force recaptured the Palovaara junction against palpably weakened resistance.

By Christmas Day, however, a new and potentially very dangerous factor had entered the tactical picture. Siilasvuo’s “air support,” one ancient and lumbering reconnaissance aircraft, reported on December 13 that a fresh Soviet division, soon identified through radio traffic as the Forty-fourth, had crossed the border and was advancing slowly westward along the Raate road. Further radio intercepts indicated that the Forty-fourth’s commander, General Vinogradov, planned to drive through and link up with the 163d as early as December 22. Finnish intelligence noted with some apprehension that the Forty-fourth was an altogether better division than the 163d, well trained and powerfully armed, with strong armored support.

About the only Finnish troops in a position to stop the Forty-fourth were the two roadblock companies of Captain Mäkinen, still dug in on their little ridge between Lakes Kuivasjärvi and Kuomasjärvi. Siilasvuo knew it was unreasonable to expect two companies, however brave and well led, to halt an entire division. To keep pressure from building against the roadblock, the destruction of the 163d was accelerated, while Siilasvuo also ordered a series of short, sharp attacks launched against the head of the Forty-fourth.

Captain Mäkinen led part of his force on a sally against the enemy’s advance guard on December 23, while three smaller Finnish detachments, hurriedly brought up on skis along the “ice road” network, simultaneously struck the Forty-fourth’s left flank farther east. A raiding detachment of 200 Finns attacked the enemy column from the vicinity of Haukila farm, just over a mile east of the roadblock, and wrought havoc among the transport elements of an antitank-gun unit, killing dozens of men and more than 100 horses before withdrawing. A battalion of JR-27 hit the Raate road from the south at Kokkojärvi, killing 100 Russians and knocking out a tank, several trucks, and a field kitchen, at a cost of only two dead to itself. The third raiding detachment, a fifty-man guerrilla company that had worked its way north of the road, became bogged down in bad terrain and was unable to make contact.

These jabs did not deal Forty-fourth a serious wound. Yet their timing and ferocity seem to have yielded results all out of proportion to the effort expended. General Vinogradov suddenly became convinced he had been ambushed by superior Finnish forces. As sniper attacks, sudden five-minute mortar barrages from the deep woods, and nocturnal ski raids continued to deprive his men of sleep and hot meals, Vinogradov lost his nerve entirely. His advance elements got close enough to the trapped 163d actually to hear its final struggles, yet his division as a whole never advanced another meter to its aid.

Siilasvuo stepped up his timetable for the destruction of the 163d. On December 23, 24, and 25, the trapped division made several attempts to break out, using up the majority of its ammunition in the process. By the day after Christmas Siilasvuo was satisfied that there would be no breakout. The Finns had been forced to give ground in some places because of the enemy’s firepower and armor, but they always retook their original positions within twenty-four hours, usually at night.

When Siilasvuo launched his all-out counterattack on December 27, the main Finnish effort was directed against the western side of the Suomussalmi perimeter. Two attacks, each two battalions in strength, went in against Hulkoniemi itself and against the main road about one mile north of those straits. Siilasvuo massed his artillery, all eight guns of it, to support these attacks. The Ninth Division’s two antitank guns were parceled out, one to each attacking force. Eight miles farther north battalion PPP-6 launched a two-pronged attack on the Kylänmaki road junction. The Hulkoniemi attack began at 8:00 A.M., the Kylänmaki junction attack thirty minutes earlier.

Diversionary and supporting actions were also mounted. Three infantry companies, “Detachment Paavola,” took up positions at Ruottula on the eastern shore of Lake Kiantajärvi. This force was ordered to advance across the lake, cutting off any Soviet movement in that direction, then turn southwest along the shoreline until it linked up with the main attacking forces near Hulkoniemi. Smaller detachments went even farther north on the eastern side of Kiantajärvi to prevent any groups of Russians from slipping out of the encirclement.

All of these attacks got underway more or less on schedule, but the main thrust against Hulkoniemi encountered savage resistance, and Detachment Paavola wasted most of its time skirmishing with small pockets of Russians encountered on the open ice, some of them in armored vehicles. The best results of the day attended the actions of battalion PPP-6. It rolled up a sizable part of the road defenses and destroyed six enemy vehicles before it too was stopped, still some distance from its objective, the Kylänmaki junction.

The second day of Siilasvuo’s general counterattack brought improved results, though still at a high cost. On December 28, PPP-6 finally secured the road junction at Kylänmaki and held it, just barely, against vigorous counterattacks. The renewed attacks against Hulkoniemi initially ran into the same furious resistance the Finns had encountered the day before. Siilasvuo was tempted to throw in his reserves, but finally decided to keep one battalion fresh in case the strangely quiescent Forty-fourth Division made any attempt to break through to its besieged sister unit. Fortunately for the Finns it did not.

Equally fortunate for Siilasvuo, at about 9:00 A.M. Russian resistance at Hulkoniemi suddenly collapsed. The pressure from so many directions against men already reduced to half efficiency by cold and hunger had finally become unbearable. Some of the Hulkoniemi defenders fled across the straits into the village, where their comrades were still holding out; others simply threw down their guns and ran out onto the ice of Lake Kiantajärvi, in the general direction of Russia. Dressed in khaki overcoats, silhouetted against the bare gray-white surface, they made excellent targets, and Finnish machine gunners on both sides of the lake cut them down ruthlessly.

The resistance in Suomussalmi village itself was fierce, and Russian machine gunners had to be pried out of cellar fortresses one by one by close and dangerous work with grenades and Suomis. But with the Hulkoniemi section of the town overrun, the eastern part could not hold out long. Soon the survivors were themselves streaming across Kiantajärvi, while the Finns brought every gun they could to bear on the ice, filling the air above it with tracers that seemed supernaturally bright against the winter gloom. Siilasvuo’s men had already plotted the probable vectors of any breakout attempt from the village; they had prepared for it by erecting barbed wire entanglements under innocent-looking snowbanks and by cutting tank traps in the ice.

By December 28 resistance in and around the village had ceased. The only sizable enemy pocket still fighting back was along the road north from Hulkoniemi. Siilasvuo now could spare some troops to reinforce the hard-pressed PPP-6. This final regimental-sized Russian pocket turned into a bee swarm, as those trapped inside made dozens of wild, uncoordinated breakout attempts. The last significant one erupted on December 29, at about ten o’clock in the morning. It resulted in negligible Finnish casualties and another 300 dead Russians.

Given the primitive nature of the terrain and the confused nature of the fighting on these last days, it was inevitable that some fairly large bodies of Russian troops would slip out undetected. Scouting parties stationed north and east of the main combat zone were able to take these groups under observation and plot their course. As Siilasvuo had predicted, they were making for the Juntusranta road and from there, presumably, the Russian border. Siilasvuo sent truckloads of machine gunners racing up the Juntusranta road to intercept, and for the first and last time in the whole campaign he experienced the luxury of calling in an air strike. Two Bristol Blenheims, about one-tenth of Finland’s entire bomber fleet, swooped down low and plastered the largest body of fleeing Russians with antipersonnel bombs. Two of the machine-gun trucks later ambushed another large party of refugees while they were still out on some open ice. They killed 400 men but suffered only one casualty to themselves.

So went that final bloody day and night of December 29–30. When the last firing on the Juntusranta road had died down, the Soviet 163d Division had ceased to exist. The Finns counted more than 5,000 bodies littered along the road from the eastern edge of Suomussalmi to the northern shore of Lake Piispajärvi. No one could even guess at how many thousands more perished in the wilderness during those disoriented breakout attempts.

Russian prisoners told their interrogators the by-now familiar litany of bad treatment, bad food, and poor leadership. One POW told the Finns that he had been visiting the shops in a little town near the Murmansk Railroad, just before the outbreak of the war, for the purpose of buying his wife a new pair of shoes. One of the local commissars had spotted him and dragooned him into the army on the spot, hoisting him by the coat lapels and demanding to know why such a fine specimen of Soviet manhood was not marching to the aid of the oppressed Finnish proletariat. The prisoner had marched into Finland without so much as one hour’s formal training; when he was captured, he still had his wife’s shoes in his pack. The Finns took pity on the wretch, gave him fresh socks, some cigarettes, and a turn in the sauna bath, the first time in four weeks any part of the man had seen soap and water. He was retained at headquarters as a kind of mascot for the rest of the campaign.

It seems incredible that while these battles were raging, only six miles away the stalled Forty-fourth Division remained in a kind of stupor. Vinogradov did finally schedule an attack against Captain Mäkinen’s roadblock on December 28, when it was almost too late to do the 163d any good even if he had broken through, but two company-sized raids by the Finns threw him into such confusion that he canceled the attack order. It is almost possible to pity poor Vinogradov. His division was highly rated, but it was heavily mechanized and trained for mobile warfare. Thousands of pairs of skis had been dumped into his supply train at the last minute before the division went over the border, but nobody knew how to use them, and the handful of men who had volunteered to go out into the forest on them had never come back. Without skis his infantry wallowed uselessly in waist-deep snow. For all its vehicles and mechanized training, the Forty-fourth Division was now blind, surrounded, and virtually paralyzed. Vinogradov had no idea how many Finns were arrayed against him. They seemed to come and go at will, striking and vanishing, and the air superiority he had counted on turned out to be chimerical. There might be dozens of Red Air Force planes overhead during the six hours of daylight, but their bombing and strafing efforts were purely guesswork, as the Finns were completely invisible beneath their vault of pine and spruce. Finally, at the eleventh hour, Vinogradov did draw up an order for an all-out breakthrough attempt; but he never issued it. No one has ever figured out why. Perhaps it was the toughness of Captain Mäkinen’s roadblock defenders. One captured Russian officer, a colonel who had taken part in the first attempts to storm the roadblock, told his Finnish interrogators that it had been like “butting your head against a stone wall.… it was unbelievable.”1

If ever an enemy formation seemed delivered into the hands of motti tactics it was the Forty-fourth Division. It resembled a twenty-mile-long link sausage, with its biggest piece, a two-mile segment that started just east of Captain Mäkinen’s roadblock, made up of a regiment of infantry, dozens of armored vehicles, and most of Vinogradov’s artillery. It was Siilasvuo’s intention to slice up the column into smaller and smaller pieces, turn up the pressure, let cold and hunger do their work, and then wipe out each dwindling pocket in turn.

He deployed his increasingly weary men very carefully, making maximum use of the “ice road” network south of the Raate road. Two task forces were organized, one under a major named Kari, the other under a lieutenant colonel named Fagernas. Kari’s units went into bivouac near Mäkälä, and Fagernas’s troops made themselves comfortable at Heikkilä. A third raiding detachment, a reinforced company, took up position at Vanka, along a crude wagon track that led toward Raate village.

The first heavy blow fell on the Forty-fourth Division on the night of January 1–2. First Battalion, JR-27, advanced to a point about two miles east of the Finnish roadblock. This move was accomplished without detection. The Finns had time to catch their breath, enjoy a hot meal, and perform a careful reconnaissance. The battalion commander, Captain Lassila, took a methodical ninety minutes to organize his attack, basing his plans on observations made from a ridge 400 yards from the Russian perimeter. He assembled two companies behind the ridge and ordered them to advance abreast of one another. Upon hitting the road, one company would swing east, the other west, and roll up about 500 yards of roadway. At that point combat engineers would move up, blow down some trees, plant some mines, and construct roadblocks in both directions. Lassila’s third company would stay in reserve behind the ridge. In accordance with the usual Finnish practice, heavy machine guns would be used to augment the limited mortar support available. Fully a dozen Maxim guns were emplaced on the ridge, from which they could fire down into the Russian perimeter, six guns to support each of the two assault companies.

10. Suomussalmi Campaign: Destruction of Soviet Forty-fourth Division

Just after midnight the attack went in. Russian sentries, stationed a mere sixty yards from the road, were taken out first, with little fuss. Then Lassila’s men swept on and hit the road hard. Although Lassila thought he was hitting an infantry unit entrenched near Haukila farm, he had actually penetrated an artillery battalion; the Finns’ nocturnal navigation had been off by about 500 yards. This mistake, as it turned out, was actually a stroke of good luck. All the enemy’s guns were trained to the west, and the Finns were among their positions before they could be reaimed, cutting down the gun crews with Suomi bursts and lobbing hand grenades into dugouts. Several of the Russian trucks mounted four-barrel flak machine guns, and these opened a tremendously noisy and colorful fire, splattering the night with multiple streams of tracer. By the time these weapons could begin firing, however, the attacking Finns were already too close. Most of the fire went over their heads, and the Russian gunners were killed at close range in a matter of minutes. In less than two hours, Lassila had taken his objective and opened 500 yards of road, with only light casualties to his men. By first light, January 2, the roadblocks, both east and west, were up, manned, and covered by mine fields.

Siilasvuo expected his adversary to react strongly to this road-cutting operation; accordingly he took the calculated risk of sending Lassila both of the Ninth Division’s Bofors guns. These weapons were manhandled forward from the “ice roads” and were emplaced by dawn, pointing east. They were not a minute too soon, as it turned out, because the enemy launched a heavy attack against the eastern roadblock shortly after 7:00 A.M. In the first fifteen minutes of combat, the two Bofors guns picked off seven tanks, leaving the road clogged with burning vehicles and in effect actually strengthening the new roadblock.

When the fighting died down, hot meals were sent forward on supply sleds to Lassila’s men. Stove-heated tents were erected on the ridge from which he had made his battle plans, and the Finns manning the road-cut were rotated periodically to that position so they could thaw out, enjoy a hot cup of coffee, and catch a few hours’ sleep. The availability of these Spartan comforts paid tremendous dividends in keeping up Finnish morale.

Conditions inside the surrounded mottis, on the other hand, grew worse by the hour as the vise of attrition and exposure closed on them. Elsewhere along the Raate road Finnish snipers, dubbed “cuckoos” by the Russians, shrouded themselves in snow camouflage, tied themselves in trees, and waited patiently, sometimes hours, for an officer to come into their cross hairs. These men fired but seldom, and when they did shoot, rarely failed to kill. With each new casualty the Russians took from their invisible tormentors, the trapped enemy seemed to grow more wildly trigger-happy. Two or three well-aimed shots from the forest would provoke a fifteen-minute counterbarrage from tanks, artillery, machine guns, and mortars, most of whose projectiles did nothing but churn snow and chew up tree branches. So many tens of thousands of rounds of ammunition were burned up on January 2 and 3 that even the more powerful mottis were thereafter forced to ration their fire.

The Finns kept up patrols and small-scale raids around the clock. They rapidly established a ring of command posts, supply depots, and camouflaged dugouts around each motti, at a distance of 500 to 1,000 yards, depending on the terrain. The ski troopers’ schedule called for two hours’ patrolling, two hours’ rest in a warm dugout, then two more hours of aggressive activity, followed by a four-hour rest period for sleeping and eating. Every two or three days, if the level of fighting permitted, each man would get a turn in one of the frontline saunas, a luxury the Finns could not do without even on a battlefield.

Targets for the skiers’ raids were carefully selected: radio sets, command posts, isolated gun pits, ammo storage, and of course field kitchens, which were listed in battle reports alongside the number of enemy tanks and guns destroyed. Anything that offered the surrounded enemy warmth, shelter, or nutrition was mercilessly eliminated. Most of the mottis ran out of food only two or three days into the new year. Horses were butchered and roasted over open fires, which in turn drew more sniper fire. The wounded and the weak began dropping in steadily increasing numbers. In such extreme cold the mortally wounded often froze with such abruptness that their corpses stiffened into grotesquely lifelike poses of activity and exertion. Death in the subarctic forests wore a Gorgon’s head rather than a skull.

Vinogradov frantically called for more air support, and the skies above his position were thick with Red aircraft during the daylight hours. But all the pilots could see were the motti formations. They bombed and strafed the surrounding forest at will, but only rarely, and then only as a matter of luck, did they tag any Finnish targets. Curiously, almost sadistically, only one of the Red Air Force’s halfhearted resupply missions seems to have been successful: three small scout planes dropped six bags of hardtack into the middle of an area where 17,000 men were going mad with hunger. By the time those pathetic parcels thudded into the westernmost motti, its inhabitants had endured five days of thirty-below-zero weather with nothing to eat but a little barely cooked horse meat.

Late in the afternoon of January 2, the Russians tried to storm Lassila’s western roadblock, but flanking fire from the woods to the south of the road turned them back easily. Strange as it seems, Vinogradov never tried a simultaneous counterattack from both east and west, the only tactic that had a chance of succeeding. By hitting first one side and then the other but never both sides at once, he allowed the Finns to deal with each threat systematically and without straining their resources.

Also on January 2 the Third Battalion of JR-27 assaulted the road farther west, near Haukila farm. Here the Russian defenses proved very strong, and the most the battalion could do was tighten its grip on the south side of the road and bring the Russian positions under increased harassing fire. Finnish mortar teams knocked out several field kitchens from their new close positions.

January 2 was a busy day. Siilasvuo also launched attacks from Sanginlampi farm against Russian positions near Eskola. It took three days of hard fighting to eject the Russians from this important flank position, but by the end of January 4 Task Force Kari had cleared the enemy from that sector and had consolidated its hold on good terrain about two miles from the road junction at Lake Kokkojärvi.

January 3 was given over to improving communications. New ice roads were laid down, poor wagon tracks were widened and their surfaces improved. The besiegers multiplied their advantage of mobility. By January 4 Siilasvuo was ready for another series of attacks. A task force under Colonel Mäkiniemi, comprised of JR-27, a battalion from JR-65, and the highly effective ski-guerrilla unit P-1, would assault the strongest remaining enemy positions in the Haukila farm sector. Siilasvuo allocated three-fourths of his artillery—six guns—to this force. Another task force, under Colonel Mandelin, consisting of two battalions from JR-65 and three attached companies from here and there, would strike the Haukila section of the road from the north at the same time that Mäkiniemi’s men hit from the south.

On Mäkiniemi’s right (eastern) flank, Task Force Kari would launch sharp flanking attacks on the stoutly defended enemy positions from Tyynelä to Kokkojärvi. Total Finnish forces allocated to Task Force Kari were three infantry battalions and the last two artillery pieces. Task Force Fagernas was to backstop these actions by cutting the road at the Purasjoki River and again near Raate village, about a mile from the Russian border.

Siilasvuo’s offensive opened on January 5 against furious, desperate resistance. Task Force Mäkiniemi’s assaults gained some ground, but all of his units were halted short of the road by heavy fire from the mottis. Captain Lassila’s men tried to widen their hold on the road by means of a flanking move on the north side of the road, but the terrain was more open and boggy there, and Lassila’s men took heavy casualties from Russian artillery being fired over open sights from within the mottis.

After these attacks had failed, Captain Lassila encountered a sergeant who had taken command of an infantry company after all three officers had been killed or wounded. The sergeant himself had been shot through a lung. Lassila stopped by the man’s stretcher and inquired as to his condition. The sergeant grinned and said that he found it much easier to breathe with two holes in his chest.

In these aborted supporting attacks, and in repelling several violent Russian probes of its roadblock defenses, Lassila’s battalion suffered ninety-six casualties in six hours. His men had been taking this kind of punishment for four days, losing about 10 percent of their remaining strength per day, and Lassila believed they had reached their limit. He requested permission to abandon the roadblocks, deploy his men under cover of the nearby woods, and try to keep the road closed by fire alone. When he finally got through to his superior officer, Colonel Mäkiniemi, he found no sympathy. Mäkiniemi’s other battalions were in no better shape and were still pressing their attacks into the teeth of savage Russian fire. Mäkiniemi himself was irate. If Lassila abandoned those roadblocks, he would be court-martialed and shot. Lassila’s men hung on.

Task Force Kari moved against the Kokkojärvi road junction at about 6:00 A.M. Despite repeated attacks his men got no closer than a quarter mile from their objective. Kari’s troops also tried to capture a section of road near Tyynelä but encountered tanks. Lacking any means to deal with armor at a distance and prevented by the sheer volume of Russian fire from getting at them with hand-thrown weapons, the Finns withdrew to the forest and urgently requested the loan of a Bofors gun.

The day’s best progress was made by Fagernas’s men. A company-sized raid caused some annoyance and loss to the Russian garrison at Raate, and Fagernas’s engineers were able to blow a small bridge about two-and-a-half miles east of Likoharju. Fagernas’s main objective, the bridge at Purasjoki, proved to be too well defended. Siilasvuo finally dispatched a company of reserves because Fagernas was making more progress than anyone else, and doing it against much stronger resistance than anticipated. One of his platoons, in fact, ambushed a truck convoy near Mäntylä, which was found to consist of fresh NKVD troops sent over from Russia only two days earlier. Eventually, thanks in large part to the arrival of the reserve company, Fagernas’s men succeeded in blowing up the Purasjoki bridge at about 10:00 P.M. Since the river’s ice was not strong enough to support vehicle traffic, this demolition effectively sealed off the Raate road west of that point from mechanized or truck-borne reinforcements.

Meanwhile the more lightweight forces of Task Force Mandelin, north of the road, wiped out a number of Russian patrols, brought several sections of the road under fire, and established a strong blocking position on the secondary Puras road, intended to stop any Russian breakout attempts by that route.

If the general attack of January 5 had not wiped out the enemy, it had put the Russians under severe strain, and blowing the Purasjoki bridge had made it almost impossible for Vinogradov to mount a coherent breakout attempt. January 6 was another day of furious combat. In a desperate attempt to break Lassila’s hold on the road, the Russians drove herds of horses into the Finnish mine fields. The resulting slaughter sickened and angered the animal-loving Finns but did nothing to shake their grip on the roadblocks. Task Force Mäkiniemi’s units finally fought through to the road in several places, knocking out Russian emplacements one by one. By the end of January 6 fighting had generally ebbed as the Russians began to run out of ammunition and stamina.

After taking time to reorganize, Mäkiniemi’s forces renewed their efforts at about 2:00 A.M., January 7. This time sizable numbers of Russian troops seemed to break. Abandoning their heavy equipment they fled into the forest, firing wildly in all directions.

Major Kari’s forces also renewed their efforts on the night of January 5–6. Since the Russian position at Kokkojärvi was too strong for a direct assault, Kari sent a company, reinforced with extra Maxim guns and one of the priceless Bofors weapons, to establish a roadblock east of that junction. This was done by 3:00 A.M., January 6, and the position held fast despite attacks of such ferocity that Kari was compelled to shift additional machine guns and another sixty infantry to the spot by midmorning.

Another of Kari’s units, ErP-15, after three hours of bitter fighting succeeded in reaching the road at a point east of Tyynelä. The Forty-fourth Division, as Siilasvuo had planned, was being hacked into smaller and smaller pieces.

By late afternoon of January 6 it was clear that some of the Raate road pockets were collapsing—substantial numbers of Russians were spotted fleeing toward the Puras track. Siilasvuo accordingly reinforced the new roadblock on that all-but-impassable rural cowpath. Other Finnish attacks at Raate village, Likoharju, and the tiny hamlet of Saukko chipped away at the shrinking Russian pockets.

Late on the afternoon of the sixth, General Vinogradov issued what amounted to an every-man-for-himself order for a general retreat. He was about twelve hours behind the situation; since midmorning his division had been melting like April snow. The last organized Russian resistance was snuffed out at dawn, January 8.

Daylight revealed a scene that staggered the senses of even the most battle-wise correspondents who were brought in to see and photograph it. From the high-water mark of the 163d Division, up at Piispajärvi, to the last burned out truck between Raate village and the Soviet border, were scattered the stone-stiff bodies of 27,500 Russian soldiers. Forty-three tanks and 270 other vehicles, trucks, tractors, and prime movers clotted the narrow road or lay, windscreens spiderwebbed with bullet holes and turrets blackened by fire, in the snowy morass of roadside ditches. The victors acquired substantial booty: four dozen pieces of artillery, 600 working rifles, 300 functional machine guns, a few mortars and salvageable tanks, and a motley but welcomed assortment of trucks and armored cars. Finnish losses amounted to 900 dead and 1,770 wounded.

As for the two Soviet commanders, they met very different fates. Zelentsov’s body was never identified. The best theory is that he destroyed his identity papers, changed into an enlisted man’s uniform, and was among the anonymous dead who failed in their last-minute attempt to break free through the woods. The Finns searched hard among their 1,300 prisoners for General Vinogradov. They were curious as to why he had not done more to relieve the trapped 163d, whose fate he must have been aware of. Some weeks later the Finns learned, from a Russian staff officer who was captured at Kuhmo, what had happened to the hapless Vinogradov. He had fled the battlefield inside a tank, somehow managed to get back across the border, and was immediately arrested by the NKVD. After a summary court-martial Vinogradov and three other surviving officers from the doomed Forty-fourth Division were marched into the woods and shot. The official reason that went on record for his execution was “the loss of 55 field kitchens to the enemy.”

1Engle and Paananen, 103.