Four days before Christmas, Joseph Stalin celebrated his sixtieth birthday. Fabulous gifts poured into the Kremlin from all parts of the USSR, including jeweled-encrusted portraits of Byzantine splendor that had taken years to create. The Soviet dictator received all the adulation his party could bestow, all the lavish gifts his people’s fertile imaginations could devise. Yet Stalin was not happy on this birthday; there was one present missing.

Some weeks before, his old crony Zhdanov, boss of the Leningrad District, had promised that his gift to Stalin would be the signed documents of Finland’s surrender. But instead of a triumphant parade to celebrate the humbling of Finland, Leningrad was threaded, several times a day, by long, slow trains, their windows covered with curtains, filled to suffocation with maimed, starving, frostbitten Red Army troops. Ten days into December, Leningrad’s regular hospitals were swamped; by mid-December so were the emergency wards that had been set up in schools and factories. By Stalin’s birthday, the long grim trains no longer even stopped in Leningrad but rolled on eastward all the way to Moscow.

Stalin was not pleased on this birthday. When a thing did not please Stalin, that thing was eliminated or changed. So it was with this infuriating, disastrous abortion of a Finnish campaign. There would have to be payment exacted for the humiliation of the Red Army, and that payment would be heavy.

Stalin was especially furious with the “Leningrad Clique” of Zhdanov, who had assured him that the Finnish war would amount to little more than a police action, a nuisance that could be concluded in two weeks. Beyond that regional sphere, his anger was focused on the People’s Commissar of Defense, Voroshilov. Nikita Khrushchev was present at one dinner inside the Kremlin, in late December, when matters came to a head between Stalin and his factotum. “Stalin jumped up in a rage and started to berate Voroshilov. Voroshilov was also boiling mad. He leaped up, turned red, and hurled Stalin’s accusations back into his face: ‘You have yourself to blame for all this! You’re the one who had our best generals killed!’ Voroshilov then picked up a platter of roast suckling pig and hurled it against the table.”12

By the third week of the war, the Kremlin’s official tone had changed from bellicose euphoria to cautious apologies and began to include the first of a long parade of excuses. The terrain was terrible, the climate was vile, the Mannerheim Line was stronger than the Maginot Line, the American capitalists had sent 1,000 of their best pilots to Finland (this last fable was reprinted, with a straight face, even in more recent, objective Soviet accounts of the war).

As has already been told, Chief of Staff Shaposhnikov had originally seen the Finnish campaign in a clear, professional, and decidedly pessimistic light; his suggestions were disdainfully filed away by Stalin. Now they were dusted off, and Shaposhnikov was brought in for high-level consultations and given the full authority of the Kremlin to back up any suggestions he might make. It was on his order that the brutal frontal assaults on the Isthmus were suspended in late December and no further adventurous plunges into the northern wilderness were launched, although he did approve vigorous action to extricate some of the units already trapped in the various mottis. Instead, the Red Army on the Karelian Isthmus would be built up to such a level of power that it could steamroll its way to Viipuri, if not all the way to Helsinki.

During the first week of January, the disgraced Leningrad Military District was reformed and renamed with the more businesslike appellation “Northwestern Front.” To exercise operational command, Stalin chose Army Commander, First Rank, Semyon Konstantinovich Timoshenko, a former barrel maker who had risen in the Red Army through sheer ability and rigorous ideological orthodoxy. His recent handling of the attack on eastern Poland, though undertaken against trifling and disorganized resistance, had confirmed his ability to handle massive formations of troops and equipment. A commanding authority figure with a shaven head, flinty gray eyes, and a powerful drill-field voice, Timoshenko was perhaps the best man in the Red Army to break the Finns. Yes, he assured Stalin when the job was first offered to him, he could crack the Mannerheim Line, but it would not be a cheap victory. He sought, and received, Stalin’s promise that he would not be held personally responsible for the butcher’s bill that would be presented after the successful campaign.

Timoshenko’s chief of staff for the coming operation would be the chief architect of the Red Army’s crushing victory over the Japanese in Mongolia, Georgi Zhukov. Zhdanov lost all authority over military matters, something he was no good at anyway, but was given a chance to redeem himself by taking over the political aspects of the new campaign. This he did with redoubled energy, anxious to regain his master’s good will, sending thousands of zealous political workers into the ranks of the Northwestern Front’s units. Only this time there was a subtle change in emphasis. The usual hackneyed drum-beating party slogans were soft-pedaled in favor of direct appeals to Russian patriotism and pride. Our country has been shamed in the eyes of the world, was the essential message, and it was up to the reorganized divisions of the Northwestern Front to redeem Russia’s honor. When the Red Army went back against the Mannerheim Line in February, the battle cries would not be “For Stalin!” but “For the glory of the Fatherland!” It made a difference. The apathy and dim-wittedness so often observed during the December battles was largely replaced by energy and determination. Unit for unit, it made the refurbished Red Army a much more dangerous foe.

In line with this new propaganda strategy, a great show was made of honoring those who had fought well in the December campaigns. In mid-January, the Supreme Soviet, with much pomp and a three-page list in Isvestia, awarded medals to more than 2,600 veterans of the early battles.

As might be expected, however, the greatest care was taken in the realm of tactics, for that had always been where the Finns’ greatest advantages lay. Sisu alone had not accounted for the Finns’ defensive victories on the Isthmus in December. The entire Soviet effort had been a tactical botch. Mannerheim likened the enemy’s performance to “a badly conducted orchestra.” The various component arms had lacked even the crudest coordination. The artillery, though massive in strength and applied against the Finns with Mongol excess, had been poorly directed; its fires merely plowed into a given general area on the map. Field commanders had not been able to call upon direct supporting fire. Barrages had not advanced in step with the infantry, so that some Soviet formations had been forced to advance through curtains of “friendly” shell fire in order to close with Finnish positions. The much-vaunted Soviet armored force had seldom acted in concert with the infantry. Tanks would charge full tilt at the Finns, break through, then simply mill about like herds of oxen, waiting for someone to tell them what to do next. The quality of Soviet leadership, from divisional staff down to platoon leaders, had been almost universally wretched, a fact that may largely be attributed to Stalin’s purge of the professional officer caste, a bloodbath that liquidated perhaps three-quarters of the Red Army’s experienced professional leadership.

Timoshenko and Zhdanov began working at the top, reorganizing and tightening control. Once that was done, they worked toward the bottom, changing tactical doctrine to meet reality, not theory, and making sure the divisions that would bear the brunt of the assault were well trained and thoroughly supported.

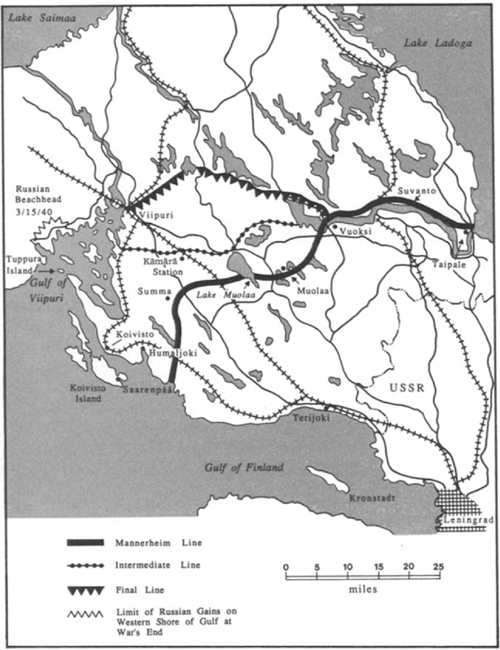

The first step was a total reorganization of the Northwestern Front. All Red Army forces on the Karelian Isthmus were divided into two corps: Thirteenth Army, under General V. A. Grendal, for the right wing on the northern Isthmus, comprised of the three divisions that had been fighting in the Taipale sector, plus new support and reserve units; and Seventh Army, under Army Commander, Second Rank, Meretskov, comprising the much-stronger right wing on the southern Isthmus.

It was Meretskov’s men who were expected to break the Mannerheim Line, and his command was strengthened accordingly. Three-fourths of his strength would be massed against the sixteen-kilometer stretch that ran Summa-Lähde road-Munasuo Swamp. Against that already battered sector, Meretskov assembled an overwhelming concentration of force: nine infantry divisions, five tank brigades, one machine-gun division, and enough artillery to achieve a front-wide ratio of eighty guns per mile.

The basic tactical approach was not subtle. It was even dubbed “gnawing through,” and it consisted first of piercing the Mannerheim Line with an armored wedge, then systematically expanding the initial puncture, and after that simply continuing to send fresh waves of troops and vehicles against the entire sector until the defenders caved in. It was clear that the Finns were already stretched thin, and it was anticipated that a massive rupture of the line at any point on the sensitive Viipuri Gateway sector would force the Finns to abandon the entire position.

Assigned to be the tip of the wedge was the Soviet 123d Division, and it was given rigorous training. After intense reconnaissance efforts, about three-fourths of the Finns’ frontline fortifications were pinpointed. Patrols even brought back samples of concrete for engineering analysis. With this data in hand, Timoshenko ordered life-size mockups of the Summa defenses constructed in a region of comparable terrain a few miles behind Russian lines. The assault elements of the 123d Division then staged three fullscale rehearsals, storming the mock fortifications, practicing demolitions on them, and perfecting their coordination with armor and gun support. Every other division earmarked for a spearhead role in the coming offensive also underwent tough, realistic training.

12. Final Russian Offensive on Karelian Isthmus

Massive shipments of tanks were brought up to replace the losses of December. Included were dozens of the almost invulnerable K. V. heavy tanks, weighing in at forty-three tons and mounting a new long-barreled 76.2 mm. cannon that fired a very powerful shell with extreme accuracy. The other most commonly used types of Soviet tank were:

• The T-26: perhaps the most numerous model used in the Mannerheim Line offensive, the T-26 had been designed using many features pirated from the newest Vickers models being tested by the British Army. The armor protection of the T-26 was weak by 1940 standards, but the trade-off was heavier firepower than was usually carried by tanks of its size: a 45 mm. gun whose design had been perfected during the Spanish conflict.

• The T-28: an interesting hybrid model, the T-28 mounted three independently rotating turrets; the largest housed a short 76 mm. cannon, while the two smaller housings carried machine guns. This arrangement enabled the T-28 to do grim execution when it prowled among Finnish entrenchments, since the triple-turret system did away with “blind spots” and made it impossible for antitank squads to get close to the vehicles.

• The B.T.: the “Byostrokhodny Tank” incorporated some of the design features of the brilliant American engineer Christie, including independent suspension with large bogie wheels and very efficient power-to-weight ratio. Compared to the average European tank, the B.T. was unusually nimble, but in December its original 37 mm. weapon had proven too weak. By January, most B.T.s deployed on the Isthmus had been up-gunned to carry a 45 mm. cannon.

Tank tactics had also been refined. No longer did the operational plan call for Poland-style breakthroughs followed by vaguely defined but wildly optimistic thrusts deep into Finnish territory. The tank units assigned to the new offensive were given realistic, limited objectives and were under strict orders not to outrun their infantry or artillery support.

But by far the most elaborate preparation made by Timoshenko concerned his artillery. The Russian Army had always believed in the power of artillery. If the panzer commander was an elite figure in the Wehrmacht, the artillerist was his counterpart in the Soviet Union. To hammer the Finns until they broke, Timoshenko assembled 2,800 cannon, ranging in caliber from 76.2 mm. to 280 mm. Behind the front, mammoth railroad weapons, nicknamed “ghost guns” by the Finns, heaved gigantic twelve-inch projectiles into Viipuri and other important areas deep in the Finnish rear. Forward observers, equipped with the latest available radio technology, would accompany every attacking formation so that massive volumes of fire could be shifted as required. Area spotting would be done by observers in captive balloons, floating 2,000 feet above the battlefield and protected by fighter aircraft. So contemptuous were the Russians of the Finns’ inability to disrupt their preparations that they did not even bother to camouflage any except their most forward batteries. The guns were just lined up wheel to wheel in the open.

On the average, each mile of front was supported by eighty cannon. At the tip of the Soviet wedge, where the 123d Division would smite the Viipuri Gateway, 108 guns were allocated. The most devastating tactical employment of artillery involved the massing of guns to fire directly against the face of concrete pillboxes. In the Lähde road sector, the most hated Finnish strong point had been the so-called Poppius bunker, an immensely strong, multichambered fortress that had been overrun, then retaken, several times in December, and that had been pummeled by hundreds of artillery strikes, but whose guns had never stopped firing. A thousand men had been cut down near that one strong point. Now, under cover of noisy diversionary barrages, the Russians emplaced a six-inch cannon only 500 yards from its embrasures, camouflaged it heavily, and waited for the signal. Other strong points, such as the “Million Dollar Bunker” that had galled the Reds as much as Poppius, were the targets of similar artillery sledgehammers, some of them as large as 280 mm. (approximately eleven inches in caliber).

When Timoshenko opened his offensive, 300,000 shells would crash into the Viipuri Gateway in the first twenty-four hours of the bombardment. Aside from direct flat-trajectory fire against individual strong points, the concentration of cannon was so great that the gunners fired “rolling barrages,” simply cranking the gun tubes up and down by increments and not needing to traverse them at all. The sound of that opening salvo, the heaviest since Verdun, would be audible in Helsinki nearly 100 miles away.

1Crankshaw, ed., 154.

2Voroshilov was lucky to escape the firing squad; he was, quite properly, sacked as a result of the Winter War blunders, but Stalin kept him around, in Khrushchev’s words, “as a whipping boy.” Doggedly loyal and subservient, he was clearly too incompetent to pose a threat; Stalin seems to have been fond of him, even as he heaped abuse on him. Voroshilov led a charmed life altogether, surviving purges, upheavals, and a serious post-Stalin denunciation in which his sins were paraded in public. He managed to cling to the skirts of power for an amazingly long time, enjoying reelection to the Supreme Soviet as late as 1962. He died in 1970, at the age of eighty-nine. A mildly pathetic figure at best, the key to his survival seems to have been that nobody, after 1939, ever took him seriously again.