Top Ten U.S. Cities by German Population in 1900

This data is from the 1900 U.S. census.

It didn’t take long for Germans to become part of the ethnic mix in North America. A single German man, Dr. Johannes Fleischer, accompanied the original Jamestown, Virginia, colonists. A year later, in 1608, five unnamed German glassmakers and three carpenters stepped off the ship Mary and Margaret to join the first permanent English settlement in what is today the United States. While the carpenters were brought to construct homes and the glassmakers likely worked their skill at making window panes, there’s an irony that these professions both could be thought of as part of the most revered of all German industries—beer-making (just think kegs and mugs!).

Since that auspicious beginning, nearly every wave of immigration to North America has included German-speaking people, and according to U.S. census data, more present-day Americans claim German ancestry than any other ethnicity. As impressive as this is, this statistic underestimates the number of people with German forebears, because many individuals have “hidden” German roots, ones in maternal lines that can be deeply obscured by surname changes after marriage.

As you read this book, you’ll see that having a German-speaking heritage, while “common” in terms of numbers, offers many distinctive opportunities for research. There’s truly a “strength in numbers” that makes looking for ancestors in this ethnic group a real pleasure—from the many individuals and organizations that share the heritage and their information about it to the wealth of written documentation that has been passed down as a result of what might be called these peoples’ Teutonic thoroughness.

Before we get started, it’s important to set the scope of this book. If you know anything about German history, you’ll know that a unified nation of Germany didn’t exist until 1871. As you’ll soon read, many German-speaking people immigrated to the United States long before 1871. This guide covers the areas that today are part of Germany, that were part of the German Empire from 1871 to 1918, as well as Austria and Switzerland. We’ll generally use the terms “Germans” and “German-speaking” interchangeably for people from the areas just described. We won’t use “Germanic,” as a rule, because historians use that term to describe the barbarian tribes who succeeded the Roman Empire in much of Europe. These Germanic tribes were the forefathers of today’s Germans and German-speaking people and also the modern English, French, Italians, Spanish, and many other groups.

This chapter will provide an overview of how German immigrants have influenced and shaped American society and help you lay a foundation for own German genealogy research.

After the slight but notable German presence in Jamestown, it would be decades before another group of German-speaking immigrants made an appearance in America and a full century before large-scale immigration began, but when that surge began, it resulted in the Germans becoming the largest free “minority group” in the English colonies. This first wave, followed by later immigration, spread the seeds of German culture so thoroughly throughout society that German traditions became a standard part American culture (take Christmas trees and hot dogs, for example).

The first German-dominated settlement in the United States was, appropriately, named Germantown and is now a neighborhood in Philadelphia. Germantown was founded on October 6, 1683 (now celebrated annually as German-American Day in the United States), when thirteen families settled in what was then a wilderness area. A trickle of Germans came to Pennsylvania in the remaining years of the seventeenth century and the first decade of the 1700s.

In 1709, some four thousand Germans who were primarily from the Pfalz region immigrated to London via the Dutch port of Rotterdam. From London, most of the Palatines were shipped to New York’s Hudson Valley and enlisted in a works project for the British Navy as a way of repaying their passage. Despite deaths from hardship and disease, about 2,100 Germans arrived in the Hudson Valley in June 1710, making them the largest single immigration of people to America in the colonial period. After the works project ended, the Germans were released to fend for themselves. Many stayed in upstate New York, but others scattered throughout the Mid-Atlantic region, including a substantial number who added to the German presence in Pennsylvania.

By the 1720s, huge numbers of German immigrants were finding cheap land and religious freedom in Pennsylvania, owned by English Quaker William Penn’s family, who were eager to make money from selling tracts in the colony. Pennsylvania became the center of a loosely bound community that historians call “Greater Pennsylvania,” which stretched from New Jersey through southeast Pennsylvania and into Maryland, Virginia, and the back country of the Carolinas. Soon Germans came to North Carolina, Virginia, and French-held Louisiana. Additional pockets of Germans developed in present-day Maine, the Carolinas, and Georgia.

From an analysis of names in the 1790 U.S. census, it’s estimated that about 9 percent of the white population (more than 250,000 people) of the United States was German. According to the census, nearly a third of Pennsylvania’s population was either German immigrants or their descendants. Most of these estimated eighty thousand German-speaking immigrants made their livings as farmers or in “village occupations” such as blacksmithing or coopering. They were primarily mainstream Protestants (Lutherans and Reformed) along with a sprinkling of sectarian groups such as Amish, Mennonites, and Moravians. A substantial number had to serve a period of time called an indenture to repay the cost of their passage to America.

The German immigrants of the 1700s, known by historians as Pennsylvanian Germans, were renowned for their agricultural prowess. They also are credited with inventing the Conestoga wagons, the precursors of the covered wagons that would later be the number-one transport vehicle of America’s westward movement. They also participated heavily in printing and publishing in the eighteenth century—producing everything from Bibles to hymn books to political flyers to forms for personal conflicts. The Moravian religious movement developed a musical legacy particularly in terms of vocal and instrumental arrangements.

Many German congregations, both Protestant and Catholic, operated parochial schools beginning in the 1700s. In many areas, these were the only schools in their areas. In the nineteenth century, as the free public school movement took hold, the church-based German-speaking private schools were mostly in urban areas with substantial German populations. Most of these schools became casualties of the anti-German sentiment in World War I.

As impressive as were the percentages and achievements of the first wave of German immigration, much more was ahead during the nineteenth century. It’s estimated that at least five million German-speaking immigrants arrived in America between 1800 and 1920. It’s estimated that roughly the same number of Americans descend from the two German waves, with the “pyramid effect” of the three- to five-generation head start of the 1700s immigrants making up for their vastly smaller original numbers.

This huge “second boat” of immigration created “German quarters” or neighborhoods in a great many cities throughout America, especially in the Midwest and Great Plains areas.

These nineteenth century German immigrants were different than their indentured predecessors. Many were entrepreneurs hoping to take advantage of the areas already settled by Germans in America. These German neighborhoods gave newcomers a ready-made market to sell their goods and services. (This change reflects the change in the economies of the German states, which finally shed a feudal-type economic system that was still in use in the 1700s in favor of capitalism in the 1800s.) The religious mix of German immigration also underwent a transformation with Protestants and Roman Catholics immigrating in almost equal numbers during the nineteenth century.

Thousands of German-Americans willingly fought in the American Civil War, mostly on the side of the Union. It’s interesting to note that many of these immigrants had fled Preussen and other German states to avoid military drafts in those home areas.

German-language newspapers blossomed in lockstep with the spread of the language’s speakers across America.

The fact that so many Americans had German blood, which was previously a source of great pride, became more equivocal in the twentieth century, especially during World Wars I and II. World War I provoked a great many Americans of German descent to downplay or even deny their roots; for example, many families named Schmidt became Smith. At the same time, many German-language publications folded, German was banned from being taught in many schools, and even churches in heavily German areas that had offered services in the tongue for the benefit of their bilingual congregations now switched to English.

Since the end of World War II, the shame of German ancestry rarely exists, but in many cases the assimilation caused by the World Wars has left many with less knowledge of their ancestors’ culture. There are few pockets across the country in which mostly conservative religious communities such as Amish, Mennonites, and Hutterites continue to speak German (or the dialect known as “Pennsylvania German,” often incorrectly called “Dutch”).

German immigrants became so prevalent in nineteenth-century America that German culture began reaching into mainstream American culture, producing a variety of effects still felt today.

In addition to St. Nicholas (“Santa Claus” being his nickname), some Germans also introduced a character called the Belsnickel, a sort of “anti-St. Nick” who dished out creative punishments to unruly children. And in 1821, Pennsylvania Germans introduced America to the Germanic custom of decorating trees at Christmas time. German immigrants also brought the Easter bunny and Easter eggs to this country.

Germany has a long history of brewing beer and immigrants brought their centuries-old techniques with them to America, where they industrialized the process and created breweries in German-American centers such as Milwaukee, St. Louis, and Philadelphia.

Ironically, two foods that now seem synonymous with Independence Day—hamburgers and hot dogs—have German roots. Germans also introduced America to casserole dishes, such as chicken potpie, which are still eaten both in their original forms and as variants such as “chicken and dumplings” in which the German origins are obscured. The same concepts are true for many other dishes such as Black Forest chocolate cake (with its still-identifiable tie to the German Schwarzwald region) and breaded veal cutlet (as what Germans call Wienerschnitzel is now usually called on American menus).

With so many Americans having at least some German blood, often hidden in maternal lineages, any listing of German-Americans can only “hit the highlights” of those representing the group’s achievements. Even arbitrarily restricting an inventory to those individuals who were German immigrants or their children is imperfect because it would leave off the two German-American presidents, Herbert Hoover and Dwight D. Eisenhower, both of whom had deep German-speaking roots. Here is just a short sampling of famous German-Americans and their achievements.

Within the world of writing and journalism, German-Americans such as Gertrude Stein, Kurt Vonnegut, and Walter Lippmann stand out as well as novelist Sylvia Plath and publisher Joseph Pulitzer (who helped give rise to “yellow journalism” before the prizes for journalistic excellence that bear his name were posthumously established). Baltimore-based H. L. Mencken might have the weightiest reputation in this category, unless it also includes German-born Thomas Nast, considered the “father of the political cartoon,” who gave us the seminal depictions of Republican elephants, Democratic donkeys … as well as a charming version of Santa Claus.

And speaking of politics, in addition to presidents Hoover and Eisenhower, the most influential German-Americans were probably Henry Kissinger, the National Security Advisor and Secretary of State under President Richard Nixon, and Carl Schurz, a refugee from the Revolutions of 1848 who served as a Union Civil War general, a U.S. Senator from Missouri, and as Secretary of the Interior (1877–1881).

Not far from politics in the sphere of acting and entertaining. Longtime Tarzan star Johnny Weissmuller originally was an Olympic swimmer, while German-born Marlene Dietrich was an actress whose mystique was difficult to top. Uma Thurman, an American actress born of a German mother, has a similar aura, while actor Christopher Walken’s father is an immigrant from Germany. There’s possibly no entertainer with a more German-sounding birth name than John Denver: The musician was originally Henry John Deutschendorf.

Some of the most famous products in American business are traceable to the Germans who founded their namesake companies. Henry J. Heinz gave his name to the H. J. Heinz Company, its world-renowned ketchup and his “57 varieties” of food products. Meat entrepreneur Oscar Mayer is synonymous with cold cuts. And Levi Strauss, of course, was the creator of the first company to manufacture blue jeans. The Rockefeller family earned millions in the oil business before most of them moved on to politics and philanthropic activities.

German-Americans didn’t just build businesses and fortunes. Father John A. Roebling and son Washington Roebling (both civil engineers) designed and built the Brooklyn Bridge. Early German immigrant Conrad Weiser, one of those 1709 Palatines, was a pioneer, farmer, monk, tanner, judge, and soldier—but perhaps most importantly, he had learned American Indian tongues as a teenager and worked as a peacekeeper on the borders of Pennsylvania until his death in 1760 during the time of the French and Indian War.

When the peace wasn’t kept, German-Americans had interesting roles in many conflicts. Mary Ludwig Hays, nicknamed and better known as “Molly Pitcher,” fought in battle during the Revolutionary War. One of the U.S. Army’s more spectacular failures, on the other hand, was laid at the feet of George Armstrong Custer, the cavalry commander who was killed with all his men in the 1876 Battle of the Little Bighorn.

German religious leaders of note have also ranged from mainstream to extreme. The Rev. Henry Melchior Muhlenberg took great pains to organize the German Lutherans in America after arriving in the 1740s. On the other hand, Conrad Beissel in 1732 founded the celibate religious order of “Brethren” at the Ephrata Cloister in Pennsylvania. George Rapp created the town of Harmony, Pennsylvania, a utopian community, in 1804. The Rappists later founded settlements in Indiana (New Harmony) and another in Pennsylvania called Economy.

The sporting world has been filled with German-Americans. The top pair from the New York Yankee’s “Murderers’ Row” baseball teams from the 1920s and 1930s were George Herman “Babe” Ruth and Lou Gehrig, both children of German immigrants. Professional golfer Jack Nicklaus’ surname retains a distinctively German spelling and his eighteen career major championships put him on top of nearly every sportswriter’s “best golfer ever” list. Pittsburgh Steelers quarterback Ben Roethlisberger has won football Super Bowls as well as a checkered reputation; during the “up” side of his achievements, he’s been a spokesman for the Swiss National Tourist Board in touting his Swiss-German heritage. Dallas Cowboys quarterback Roger Staubach, on the other hand, was a college Heisman Trophy winner and professional Hall of Famer, all while compiling a squeaky-clean image. And did you know that Pilates is not just an exercise class—he was a person, too? Joseph Hubertus Pilates overcame childhood sicknesses by creating a regimen of fitness exercises that bears his name today and includes yoga, Zen, and ancient Greek and Roman traditions.

Now that you have a better understanding of German roots in American culture, you can start exploring the German roots in your family tree. The evidence that you have German-speaking ancestry may be very obvious or could be inconclusive. In taking your ancestry “out for a spin,” so to say, you want to proceed with caution … and be prepared for a U-turn or two. Even proof that seems extremely obvious could be misleading—in both directions. Take for instance someone with the surname Schneider, which is the German word for “tailor.” It would seem self-evident that this ancestry will be German; however, there are instances of ethnic English named Taylor who moved to a German-dominated area of America and changed their surnames to fit in. More often this “translation” worked the other way, such as families with the German name of Klein taking the surname Little.

Other ways in which “German-ness” may be hidden are more convoluted. Remember those 1709 Palatines we talked about earlier? Some of this group never made it across the ocean; they were settled in Ireland. One such family adopted the name McSheffley, which kept its German-speaking origins obscured until a descendant found evidence that the original name of this family was Schaeffer.

Ethnic misnomers can also obscure German roots. Statisticians were baffled when the results of the 2000 census showed the number of Pennsylvania residents claiming “Dutch” descent had doubled between 1990 and 2000 despite that state having little in the way of immigration (or even migration from other states). Some speculate that many in the state who call themselves by the ethnic misnomer of “Pennsylvania Dutch” are actually descendants of Germans who came in Colonial times, but they have lost this connection and assume Dutch is their heritage. Another possibility is the fact that nearly all of these Colonial immigrants left continental Europe from the Dutch port of Rotterdam regardless of their country of origin.

An additional complication is the fact that “German-ness” is itself a complicated concept because a united German state didn’t exist until 1871. Plus, nearly all of Austria, much of Switzerland, and the microstates of Luxembourg and Liechtenstein are populated by German-speaking people, and many ethnic German enclaves once dotted Eastern Europe. All of this geographic ambiguity is proof positive that proceeding with caution is the best strategy. Remember, this guide covers the areas that today are part of Germany, that were part of the German Empire from 1871 to 1918, as well as Austria and Switzerland. We’ll generally use the terms “Germans” and “German-speaking” interchangeably for people from the areas just described.

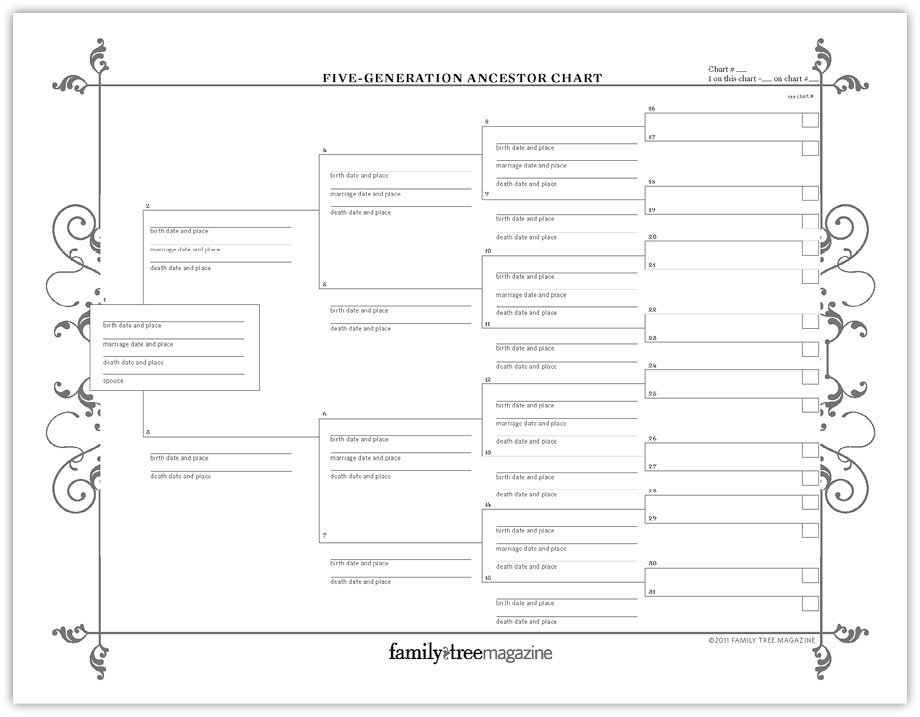

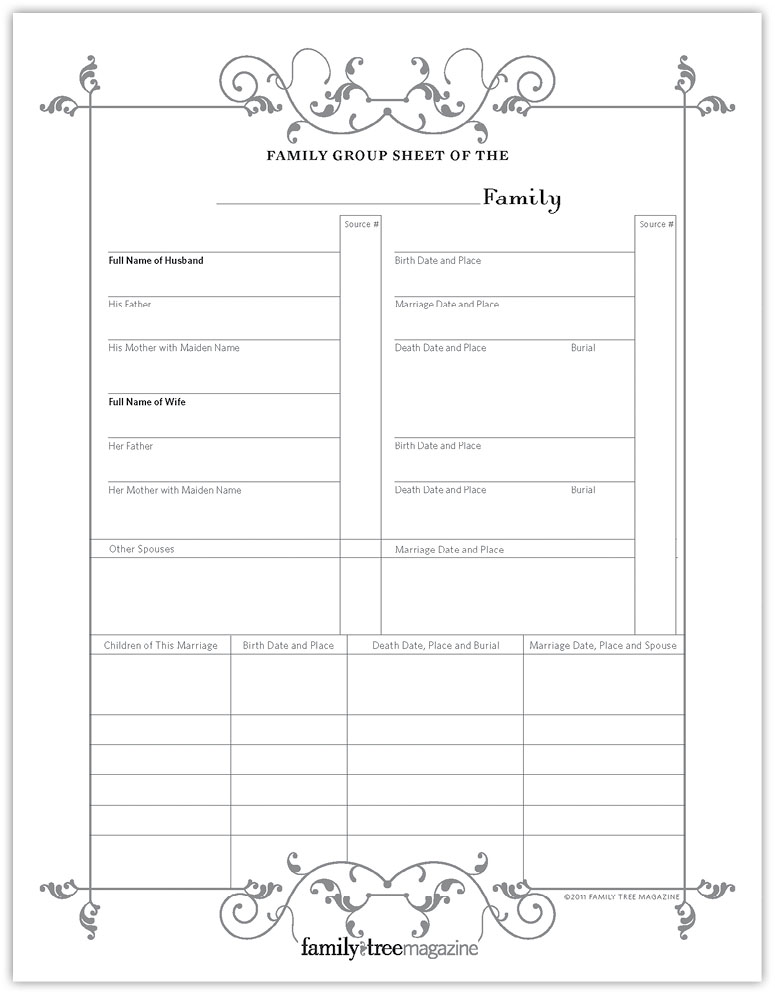

The best way to start your genealogical search is to list everything you already know (or think you know) about your family. You’ll want to ascertain: names; dates of birth, marriage, and death; and other biographical facts about each ancestor’s life. Keep this information organized and easy to reference by using two standard genealogy forms called a pedigree chart and a family group sheet.

A pedigree chart is a graphic listing the direct-line ancestors of a particular individual. In addition to the individuals’ names, the chart usually includes dates of birth, marriage, and death. Download a digital copy of this chart at <familytreeuniversity.com/germangenealogyguide>.

Sample pedigree chart

A family group sheet captures detailed information of a single nuclear family. It begins with a husband and wife and lists all children born of that marriage. It includes birth, marriage, and death dates and often includes names of children’s spouses. Sometimes information on the places of vital events is shown, too. Download a digital copy of this chart <familytreeuniversity.com/germangenealogyguide>.

Another helpful chart is a biographical outline chart, available at <familytreeuniversity.com/germangenealogyguide>. Each chart is dedicated to a single ancestor and you use it to record important details about that ancestor’s life including education, military service, marriage, children, illness, religious milestones, migrations, residences, jobs, family events, land purchases, court appearances, deaths, and burials.

Sample family group sheet

While you can compile these charts and sheets by hand, it’s easier to use computer software to manage the genealogy information you collect. There are a number of genealogy software programs available. Included with virtually every piece of genealogy software are ways to print selected information from your database into a chart or sheet. There is also a standard format for exchanging data between different genealogy software programs called “Genealogical Data Communication” or GEDCOM, so you can easily share information with fellow researchers.

A distinctively German method of portraying a direct-line pedigree is called an Ahnentafel (literally, “ancestor table”). In this table, you are numbered as “1,” your father as “2,” and your mother as “3.” In succeeding generations, each father has a number double that of his child, and the mother’s number is double (that of the child) plus 1. The Ahnentafel is especially useful for pedigrees that stretch back centuries in time since plotting such an ancestry on a pedigree chart would make the resulting chart enormous.

When you start your genealogy research, always start with yourself. Your research will be most effective if you work backwards from yourself instead of starting with a potential distant ancestor and trying to work forward to establish a connection. You are number one on your pedigree chart. Complete a family group sheet for the nuclear family you have with your spouse or significant other. Then add your parents to your pedigree chart and create a family group sheet for their marriage, and continue up the chart as far as you can.

A great way to gather information for your research is to create an oral history of your family. This process isn’t as intimidating or involved as it sounds. It simply involves asking family members to share their memories of the family. You’ll want to start by interviewing your closest blood relatives—parents and grandparents if possible—but don’t limit yourself. If there are friends of your grandparents or great-grandparents still living, interview them. Don’t rule out distant cousins, either. While they may not be close by blood (or even close in any physical or emotional way to the current generation), family artifacts from common ancestors—items such as family Bibles or papers from an immigrant—may have made their way down in a cousin’s line. Interviewing them may open the door to sharing these photos or documents in some way.

You can interview in person, over the phone or via Skype, or over e-mail. Whatever method you use, you’ll want to record the interview in some way. You can use a basic tape recorder, a digital recording device, or even a video camera. When you set up the interview, let the person know you want to record the conversation and ask him what method would make him most comfortable. Be sure to transcribe the interviews (at your leisure) so you have a backup copy in a version that is not dependent on technology (which can quickly become outdated and unavailable).

Bring your pedigree chart and some family group sheets and ask the person you are interviewing to help you fill them out. Then ask for details about each person you add to the chart. Ask for a description of the ancestor’s personality, occupation, where he lived. Find more interview tips online at <familytreemagazine.com/article/Oral-History-Interview-Question-Lists>.

During the interview, be prepared to let the person you’re interviewing wander off into tangents. Many “family stories” might not directly impact your research, but they will give a more complete understanding of your ancestors. Genealogists have been called either “family historians” or “ancestor collectors.” The former attempt to form detailed portraits of their forebears, while the latter settle for names, dates, and little else. Oral history will help turn an ancestor collection into a family history! For example, in an interview with Great-Aunt Emily about her mother’s family, Emily shared that her sister never wished to be called “Nanny” by her grandchildren. Emily and her sister had such bad experiences with their own ancestress who used “Nanny” as her familiar nickname. Emily also explained that her aunt Katie never got along very well with Emily’s mother (Katie’s sister) or Katie’s other siblings. Emily told of the family’s experience with the Influenza Epidemic of 1918–1920, when Aunt Katie refused to help siblings who were sick. Katie and her husband would stop on the road and yell from their car. “Guess who was the only family member to get the flu and die?” Emily asked, the answer written on her face. Such family stories, when verified as much as possible by other records, reveal character as well as sterile facts. Some of the stories that your interviewee will tell you might not seem relevant to your search at the time, but you have no way of knowing what twists and turns your research may take, so bear with them.

Many families have chapters they’d like to keep private. If you think a topic will be sensitive for the person you are interviewing, leave it for the later part of the interview. Starting with a controversial topic might shut down the interview quickly and deprive you of basic information. On the other hand, don’t shy away from asking the tough questions. It may be your best and only chance to solve a family mystery.

Don’t put off interviewing family members, especially older ones. Memories fade—sometimes quickly, and you never know what tomorrow will bring. We can reasonably assume that paper records will be around for generations, but we never know just how much time we have with loved ones.

You know your birth date and place and the other important milestones of your life, but what evidence do you have to prove these events to others? You have your birth certificate, marriage license, and other vital documents, and all of these records are likely in your home. Any document, record, or artifact that contains genealogical information and is found in your home is called a home source. Home sources are the first sources you should check when you are starting your genealogy research. The family Bible, scrapbook, funeral cards, birth announcements, wedding announcements, newspaper clippings, yearbooks, and city directories are all examples of home sources. When you interview family members, ask them if they have any home sources they can share with you. Bring a camera or portable digital scanner to make copies of these documents.

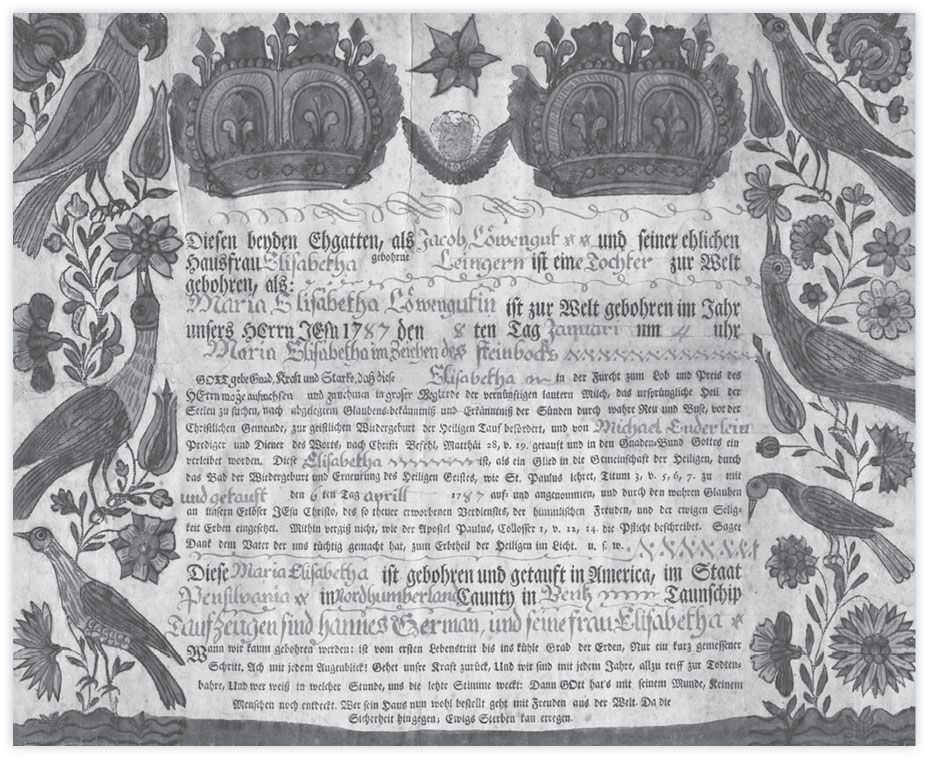

As you search for home sources, be on the lookout for anything that includes evidence of “German-ness” (for lack of a better word), such as:

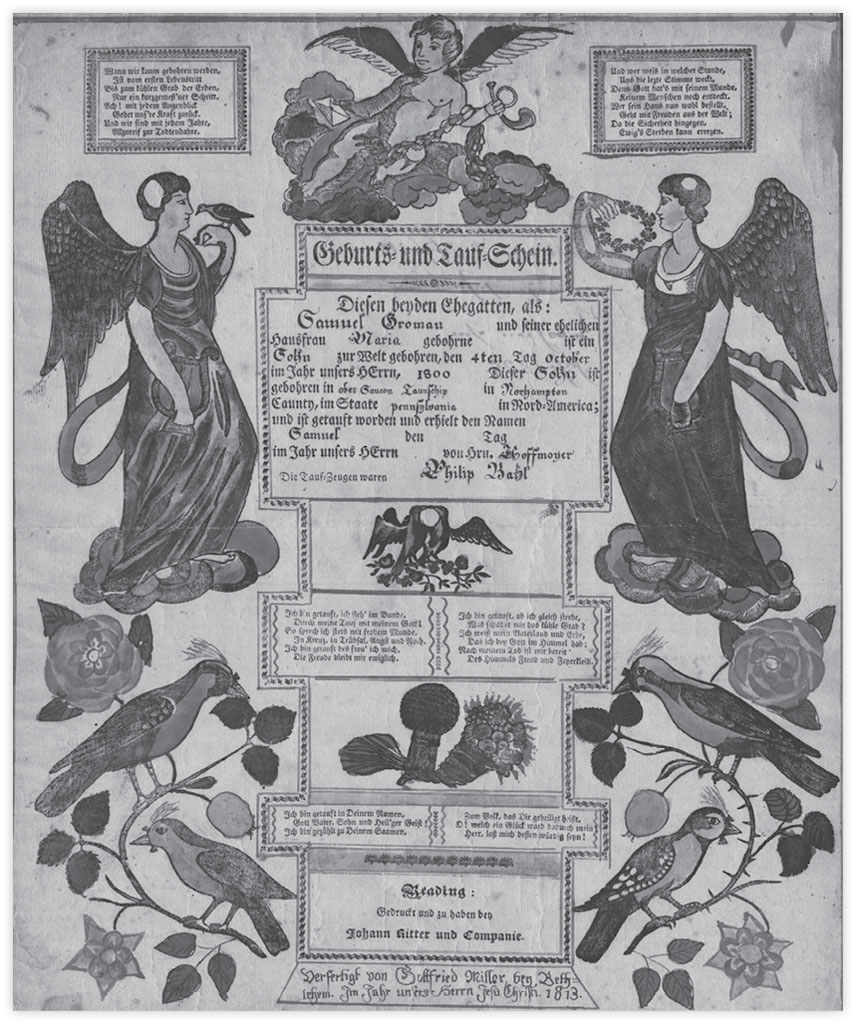

This decorative certificate is not an official record, but an example of a home record you may find in your ancestor’s papers. This certificate was printed at Ephrata Cloister in northern Lancaster County, Pennsylvania. It was likely printed for schoolmaster Henrich Otto (1733–circa 1799) as the art and the infill (handwritten genealogical data) is attributed to him. The certificate was infilled for Maria Elisabetha Loewengut, daughter of Jacob and Elisabetha (Lein[in]ger) Loewengut. Maria Elisabetha was born about four o’clock in the morning on January 8, 1787. She was born in Penn Township, Northumberland (now Snyder) County, Pennsylvania. Courtesy of the Earnest Archives and Library.

While these home sources are an excellent place to start, the information they contain may not be 100 percent reliable or accurate. You’ll have to evaluate the source to determine how accurate it likely is.

This is another example of a decorative certificate. It was made for Samuel Groman, son of Samuel and Maria Groman. Samuel Groman, Jr. was born October 4, 1800, in Upper Saucon Township, Northampton County, Pennsylvania. Samuel’s certificate was printed about 1810 by Johann Ritter in Reading, Pennsylvania. It is signed by the scrivener Gottfried Miller of Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, and dated 1813. It is not unusual that Samuel’s certificate was completed years after he was born. Courtesy of the Earnest Archives and Library.

In evaluating sources of information, genealogists make distinctions between what are called “primary” and “secondary” sources. Primary sources are generally defined as those created in relatively close proximity to the event in question by someone in position to know the truth of the facts asserted and include such documents as civil birth, marriage, and death certificates; church baptismal and burial records; tombstones; wills; deeds; and U.S. census schedules. The definition of a secondary source is, essentially, “everything else,” and the most prominently used of these sources are compiled family genealogies and county biographical histories. Each piece of data found in secondary sources should be traceable to either to one primary source or a conclusion based on one or more primary sources.

Primary sources are further separated into those that are originals (or photocopies of originals) and derivatives (such as published abstracts of records or hand-copied versions of original wills and deeds). There’s a good chance that hand-copied versions and abstractions will include errors, so it’s best to find original primary sources whenever possible.

It’s not uncommon for different sources to give conflicting information about a life event. In this case, give more credence to the source created more closely to the event. For example, if two sources for the date of death are an obituary and a tombstone, the obituary is more likely to have the accurate date than a memorial marker that might have been carved months or years later. Or if two sources for a date of birth are a baptismal record and an obituary, the baptismal record is likely more accurate because it was created closer to the person’s birth.

It’s important to note that oral histories are secondary sources. We all know how faulty our memories can be. You’ll want to find sources that confirm the dates and stories you hear. Keep an open mind concerning family stories, especially when these stories involve legends about family origins or contain “unbelievable” information. You’ll want to attempt to prove those stories and legends with other sources. It’s important that no family story be ignored, no matter how “crazy” it may seem, because nearly all contain at least a small kernel of truth.

Home sources are simply the starting point for your research. After you’ve collected all the data from these sources, you’ll want to verify the information and add to it by exploring additional historical records. This book will help you find additional genealogy records and sources specific to German genealogy.

There are many genealogy research methods, and as you gain research experience, you’ll recognize that each search is as individual as the ancestor you’re researching. Just as no two people are alike, no two searches are completely alike. A “typical” search (with the caveat that the circumstances of each case will lead to additional steps in some cases and shortcuts in others) involves the following steps, all of which will be detailed in future chapters:

1. SEARCH ONLINE. The Internet gives genealogists access to scads of information. Paid subscription databases, such as Ancestry.com <ancestry.com>, and free databases, such as Family Search <familysearch.org>, let you search millions of digitized records with a few keyboard strokes. You can also search the websites of repositories and organizations and use genealogy forums and message boards to connect with other individuals researching the same family. Much of the information found online will be faulty in some way, but it’s an easy starting point for a beginning genealogist. Remember to find primary and secondary sources for all of the information you find online to add credibility to your research.

2. VISIT OR REQUEST RECORDS FROM AMERICAN REPOSITORIES. More genealogy records are put online every day, but it’s important to remember that not all records are online. Some records may be available only at American repositories such as a county courthouse or state archive. If you can’t visit these repositories in person, you can correspond and request records be mailed to you. If you are corresponding by mail, be patient. It can sometimes take more than six months to receive a reply. Even repositories that have made substantial collections of their documents available online will have additional resources on-site. And those that have not “gone digital” often have made their catalogs of holdings available on the Internet, giving researchers a leg up by being able to put together a listing of the books, microfilms, or original documents they wish to research in advance of the visit. In some cases, Internet sites will merely have indexes or abstracts of documents and the repositories will offer access to the originals, which can then verify and/or expand upon the information found online. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints’ Family History Library (FHL) in Salt Lake City, Utah, has a well of genealogy documents. You can search its catalog and many records online at <familysearch.org>. If you find a record you need but can’t make it to Salt Lake City, you can request that the material be sent to a local Family History Center in your area. Family History Center locations are listed on the website.

3. CORRESPOND WITH REPOSITORIES IN THE OLD COUNTRY. One of your goals in researching your German immigrant ancestor is finding the ancestor’s old country Heimat (or hometown). As you search records in the old country, you’ll need to correspond with repositories. Future chapters will help you identify these repositories and compose letters and e-mails. You also may someday want to travel to the Heimat, and corresponding with individuals in Germany in preparation for that trip is often the final step of a successful genealogical search. It really doesn’t get any better than walking where one’s ancestors walked and learning firsthand about their life, times, and place within the context of larger history.

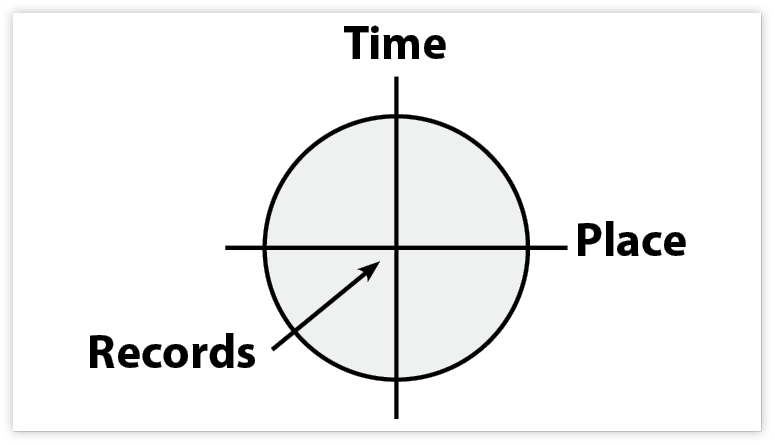

Time and place “cross hairs” graphic

As you start your search for your German roots, there a few general genealogy concepts that will serve you well in your search.

The most important genealogy concept is using time and place as a kind of cross hairs for your research. With this concept, you use both the time in which your particular ancestor lived and the place where he lived to determine what records may be available about that ancestor. You must put yourself in the time and place of your ancestor to accurately determine what documents might possibly exist. For example, it’s useless to search for an official birth certificate for an ancestor born in Georgia in 1850 because Georgia didn’t start issuing official birth certificates until 1919. Likewise, you should be aware that an individual enumerated in the 1840 U.S. census in Cumru Township, Pennsylvania, might show up in Spring Township in the 1840 head count without having moved in the interim, since Spring was created from Cumru during the decade.

KEY TAKEAWAY: Before you start looking for specific records for an ancestor, first research the ancestor’s area to get an understanding of record-keeper standards during your ancestor’s time.

Many ancestors remain “lost” because researchers fail to try alternative spellings of their ancestors’ names, especially surnames. Standardized spellings—for all words, not just names—is a much more modern concept than we seem to believe. You’ll find greater success if you look at each surname as part of a “set of variant spellings” rather than exclusively using the present-day spelling.

When you do encounter a change in spelling, it’s important to analyze the record before jumping to the conclusion that the ancestor himself changed the spelling (or an official changed it for her). In most cases, the record represents either how the ancestor wished to spell the name at that particular time, or some official’s phonetic attempt to represent the name. Both of these situations were subject to changes “back and forth” rather than a steady evolution from one “original” spelling to a “modern-day” one. For example, take a name used as both a given name and a surname in German: Hermann. In most cases, the final “n” will be dropped in America, conforming to the English spelling of the word man. But because the original German pronunciation sounds something like “Hair-mahn,” you’d be wise to also check for a spelling such as “Hairman” or, because in some cases the initial Hs are not voiced in English, the name might even show up in records as “Airman.” We’ll go into much more detail on German names in chapter six to help you with this concept.

The primary (or even sole) goal of most family historians is finding information about their direct-line ancestors. But expanding your search to include the siblings of your ancestor, a practice called “whole-family genealogy,” can make your genealogy more fulfilling … and accurate. Records for an ancestor’s siblings may include information about direct-line ancestors in the preceding generation. For example, you may be unable to find the names of your ancestor’s parents, but you’ve found death certificates for a young sibling and an older sibling of your ancestor. The same people are listed as parents on the death certificates, so you can reasonably conclude that these people are also your ancestor’s parents.