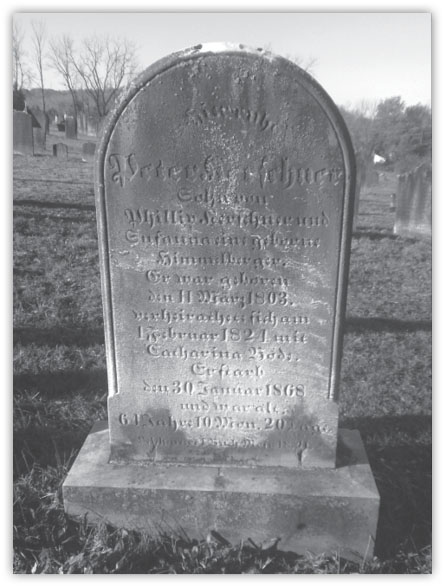

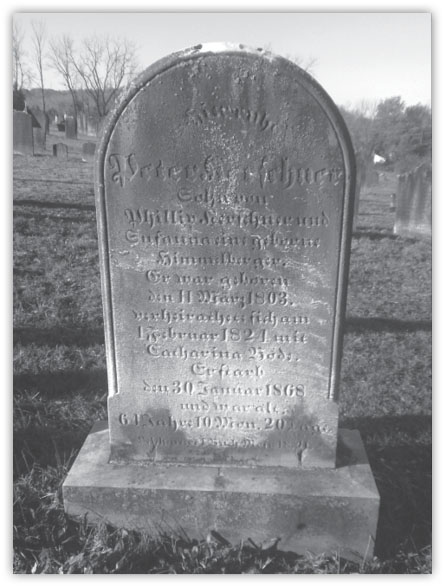

Peter Kerschner’s tombstone

Chapter five helps you locate records for your ancestor’s village of origin, but it doesn’t address the proverbial “elephant in the room”: Those records will be written in German. Do you need to be fluent to understand them? Not necessarily, as you’ll learn in this chapter. We’ll look at three interrelated language skills (vocabulary, Gothic printed font, and cursive script) that will help you cross the language barrier and give you an extensive primer on German phonetics and names to help you make sense of the records you find.

It’s a respected rule that using “always” or “never” in a sentence is an excellent way to be, well, always wrong and never completely right. However, there’s one exception to that rule: Never rule out a person as your ancestor simply because the name isn’t spelled the same. This chapter will have lots of emphasis on names because they’re a genealogist’s “stock in trade,” so to say, but we’ll explain about the language in general, too, with the hope that you’ll consider learning at least a smattering of German to help you research more records on your own.

It’s been said that if you can learn the complexities of English, such as the many spelling quirks and “rules that are exceptions to rules,” you will find learning German is a breeze because its spelling and pronunciation rules are much more predictable. English and German share the same linguistic roots (both are Germanic tongues, as opposed to the Latin-based Romance languages such as French, Spanish, and Italian), and many words have similar spellings and pronunciations.

If you can arm yourself with a basic vocabulary of a few dozen words (you might want to call this “tombstone German” because many of the words you’ll need are found on the older, detailed German-language memorial markers, especially in America), you’ll be able to read many of the genealogical records that are written in German.

You’ll need some German language skills for: church records in both Europe and America; private certificates; courthouse documents such as wills and deeds; and newspapers and websites of German towns and archives. And if you can expand that knowledge to a few hundred words, you’ll be able to make sense of fairly complicated records and even have some rudimentary conversations in the German language.

German grammar is somewhat more complicated than English, but the amount of grammar you need to do your genealogy work is limited. A few key grammar principles to keep in mind:

The German alphabet has relatively few differences compared to English. There is a character called the “S-set” that is used for a “double s” and looks like this ß (it is often mistaken for an upper case “B”). More importantly, many German vowels can carry an Umlaut, shown as a pair of dots written over the vowels a, o, u, and y. The Umlaut takes the place of an e (recently, German language officials have decreed that the e should be written out instead of using the Umlaut, but this is only in the process of gaining acceptance and of course the hundreds of years of records containing Umlauted words will not be affected!). The major effect of the Umlaut is that it profoundly changes the pronunciation of the vowel and therefore may create radically different phonetic spellings of German names in America.

Another thing you’ll note in German records is that those writing them used abbreviations liberally (even to the point of abbreviating names!) and felt free to use hyphenations at the ends of lines of handwritten documents at any point in a word (not just between syllables as is traditional in English).

Among the Internet tools that will help you gain some language proficiency (or make up for what you’re lacking) are Google Translate <translate.google.com> and the leading online German-English Dictionary, LEO Deutsch-Englisches Wörterbuch (German-English Dictionary) <dict.leo.org>. Google Translate has a toolbar that will pop up above a German-language website and allow you to click on it for a translation of that site. The caveat here is that not all sites translate completely; sometimes, entire blocks of text do not translate and often the Google translations will give only a rough sense of the meaning in English. You can copy and paste any untranslated blocks of text into the text box on the Google Translate site <translate.google.com/#de/en>. The LEO dictionary online is great for translating individual words. You can attempt entire sentences with it, but it may not help if the sentence is not constructed in correct German.

Until the early 1940s, all German-language printed material was published in a font called Gothic or Fraktur. In German-speaking areas, newspapers, journals, genealogy surname books and family collections, the Meyers Gazetteer profiled in chapter five, the printed “boilerplate” found in church and civil registers as well as on private certificates, and most tombstone inscriptions all used this font.

You’ve likely seen this font before because many newspaper nameplates still are printed in it. But it’s worth studying because it is a very difficult font to decipher because it has many similar-looking letters. As a matter of fact, the font isn’t just difficult for the human eye; only within the last couple of years has optical-character recognition software been developed to allow for the scanning of German-language newspapers printed in the Fraktur/Gothic.

In uppercase letters, the most confusing letters are the S, which is often mistaken for C, E, and G, and the interchange of the following pairs of letters: the V and B; I and J; and N and R.

In lowercase letters, h, n, and y are difficult to differentiate; f and s look alike, as do c and e and i and j.

The lowercase k can also cause confusion because it looks like a Roman font letter l with a line through it. A chart with the full alphabet in Fraktur/Gothic font appears in the appendices.

It’s helpful if you learn to differentiate the font’s lookalike letters and practice a two-step process in working such text:

Step 1: Write or type out the original German in handwriting or typing to which you are accustomed.

Step 2: Use your transliterated text to make a translation from German to English (do this either from the German vocabulary knowledge you’ve acquired or use an online tool).

Here’s an example of using the two-step process on a tombstone (slashes indicate the end of each line of the inscription):

Step 1: Transliterated from the Gothic font:

Hier ruhet / Peter Kerschner / Sohn von / Phillip Kerschner und / Susanna eine geborne / Himmelberger. / Er war geboren / Den 11 Marz 1803, / Verheirathet sich am / 1 February 1824 mit / Catharina Bode. / Er starb / Den 30 January 1868 / und war alt / 64 Jahre, 10 Monate, 20 Tage / Leichen Text: 1 Buch Moses 48:20

Peter Kerschner’s tombstone

Step 2: Translated into English:

Here rests / Peter Kerschner / Son of / Phillip Kerschner and / Susanna “a born” (nee) / Himmelberger. / He was born / the 11th March 1803, / Married on / 1st February 1824 with / Catharina Bode. / He died / the 30th January 1868 / And was aged / 64 years, 10 months, 20 days / Funeral text: Genesis 48:20

Reading handwritten records requires a few more degrees of skill. You must not only adjust from one individual’s script to another but also deal with slips of the writing pen and just plain awful handwriting. The handwritten records that you’ll deal with the most are church records (detailed in chapter eight), private certificates, wills, deeds, and letters or diaries.

A good way to start learning German cursive script is to obtain a script key of a common “standard” handwritten script such as Kurrent or Sütterlein. The book If I Can, You Can: Decipher Germanic Records by Edna Bentz contains one of the best script keys. Bentz’s key displays a dozen or more variants for each letter of the alphabet. A very basic script key for both Kurrent and Sütterlein can be found in the appendices of this book.

After you have this script key, write your own surname (or that of an ancestor you’re seeking) as a guide for what to look for in handwritten records. You may need to write your name hangman style, constructing the word letter-by-letter, starting with those you know and then working to those letters that give you more difficulty. Some have likened the process to unraveling a code, only instead of using cipher substitutions, you’re putting that old-style handwriting into one you can better understand.

After writing out the name you’re seeking, the best way to learn how to decipher the script is to start with documents that use a limited vocabulary, such as church records or private certificates. As you gain more confidence in your work you can gradually build toward more challenging records such as deeds and wills and eventually letters or diaries. But realize that even experts with years and years of experience will be uncertain at times because either the handwriting is ambiguous or the original record has deteriorated.

Phonetics plays a key role in determining whether the German name you find in American records is likely to be the same name used in European records. Remember our rule from the beginning of this chapter: Never rule out a person as your ancestor simply because the name isn’t spelled the same. That’s because, first and foremost, standardized spelling—even “in concept”—is no older than Noah Webster (1758–1843). And given that English-speaking clerks were recording documents (U.S. census, wills, deeds, etc.) for German-speaking common folks (who were often scantily educated), there was lots of opportunity for any number of spelling variations to be used. It’s best to think of a name’s spelling as elastic and acknowledge that there’s a set of different spellings that all possibly could be used for your ancestors.

There are excellent in-depth resources for learning about German names listed in the appendices; the best volume is German Names: A Practical Guide by Kenneth L. Smith, which is filled with helpful examples regarding phonetics, dialectical shifts, and other finer points.

Vowels with Umlauts (shown as a pair of dots written over a, o, u, and y; it takes the place of an e) are responsible for many spelling variations. Here are a few examples for illustration:

Sample certificate with translation of script

In cases of vowel combinations that did not include Umlauts, it was generally the second letter of the vowel combination that “spoke”; for example:

Because of these pronunciations, a speller unacquainted with German phonetics would reverse the letters when writing out the name. In addition, persons of Jewish origin with such German names usually pronounced their names by using the sound of the first vowel.

In German, a number of consonants are either pronounced differently than English or can be confused unless heard distinctly. Some examples include:

Most German commoners acquired their surnames in the Middle Ages, sometime around the 1300s, and for most areas (with the conspicuous exceptions noted later in this section) those surnames were fixed from one generation to another, disturbed only by variations in phonetics. Most of the surnames adopted came from occupations, geography, characteristics, or patronymics.

Occupational names, most of which are distinguished by the endings –er or –mann, are very common in German and therefore are often more difficult to trace (the joke among German genealogists is that everyone has at least one “Johannes Mueller”/John Miller ancestor). A few examples of this type of surname are Schneider (tailor), Schmidt (smith), or Fenstermacher (window maker).

Geographic names can be fairly specific or generic. A Marburger probably has an ancestor who was living in the German city of Marburg when surnames were adopted. A Schweitzer either was living in or a descendant of a family from Switzerland. Dieffenbach simply means “deep creek,” of which there are many in Germany.

Characteristic names run the gamut from presumably complimentary to, well, not so complimentary. They include names such as Lang (long), Schwartzkopf (black head), Weiss (white), Klein (short), Altmann (old man), and Dick (fat).

Many Germans have patronymic names—surnames derived by combining the father’s given name with some form of Sohn (the German word for “son”). Examples are Hansen or Jacobsohn. Some areas of Germany used changing patronymic surnames into the nineteenth century. This means the surname could change with each generation as the children of the new generation took the name of their father as their surnames. For example Jacob’s son, Robert, has the surname Jacobsohn and Robert’s son, Johannes, has the surname Robertsohn even though Robert’s surname is Jacobsohn. The areas that used changing patronymic surnames were Ostfriesland and Schleswig-Holstein, which is not surprising because these are the areas of Germany closest to Scandinavia, where patronymics also survived into the 1800s.

Another complication to be aware of are so-called Hofname (translated as either “farm names” or “house names”). This happened most often when a farm owner’s daughter inherited the land and her husband took on the farm name as his own. Children born prior to the inheritance were baptized under the father’s original surname, then changed their names later; those born after the inheritance used the farm name from birth. The Hofname surnames were most common in the border area between the German states of Niedersachsen (Lower Saxony) and Nordrhein-Westfalen (North Rhine-Westphalia) though they’ve been found in other places, too.

There are two German naming traditions genealogists should know. The first is that German children were given two names, and the second name, not the first, is what you will find in records. This is because German boys almost always were baptized with the first name Johannes (or Johann, abbreviated Joh.). German girls were baptized Maria, Anna, or Anna Maria. (This tradition started in the Middle Ages). This means a family could (and commonly did) have five boys with the first name Johann. You can see the high potential for confusion until you understand that the first name doesn’t mean a thing. The second name, known as the Rufname or “nickname,” is the name the child would answer to and use to identify himself. Outside of baptism records, a person’s “full name” was almost never used again. Instead, only the Rufname and surname would be used in marriage, tax, land, and death records. So in a family with boys Johann Friedrich, Johann Peter, Johann Daniel, etc., the children would be called by (and recorded as) Friedrich, Peter, and Daniel. Usually, the name Johannes marked a “true John” who would continue to be so identified.

By the nineteenth century, more families gave children three names. Again, it was typical that only one of the “middle” names was used throughout the individual’s life. Roman Catholics typically named their children using only the names of people declared saints, while most Protestant groups expanded the canon of names to include names form the Old Testament or even non-Christian mythology.

The second naming tradition involves nicknames, often called Kurzformen, meaning “short forms.” In English most nicknames are created by dropping the last syllable of the given name (for example, Christopher and Christine become “Chris”). Germans, however, often shorten a given name by dropping the first part it. Some of the many examples (using more authentic but understandable German spellings) are: Nicklaus becomes Klaus, Sebastian becomes Bastian, Chistophel becomes Stophel (and Christina becomes Stin or Stina), Katharina becomes Trin. It’s important to note that these familiar forms are used in church or other records, even though by today’s standards we might expect full or formal names to be used.

Researchers often hope that a naming pattern will provide clues about the given names of previous generations. In German-speaking areas, children were almost always named for one or more of their baptismal sponsors. The most common pattern would be for sons to be named in this order: first born, for father’s father; second born, mother’s father; third born, father of the child; fourth born and on, uncles of the child. The same pattern applies to daughters but using the mothers’ names (father’s mother, mother’s mother, mother of child, aunts). Given names for children who died young (a common occurrence in centuries gone by) were reused by the family for children born after the deaths. There are even some documented instances where families used the same name for two children who both survived.