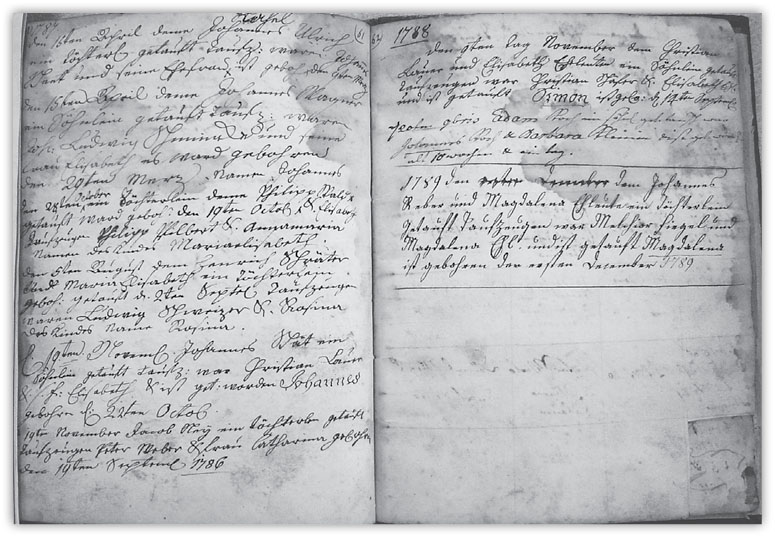

Sample of church record written in a narrative format (first record book of Bern Reformed United Church of Christ, Bern Township, Berks County, Pennsylvania)

While your German-speaking ancestors left many types of records, German church records solve more German research problems than any other documents. There are several reasons for this. First off, most Germans belonged to Christian religious denominations that kept registers with genealogically significant information. Secondly, despite gaps created by wars and neglect, the German penchant for record keeping has maintained a large percentage of these registers, which date back centuries. Finally, church records help genealogists with German roots on both sides of the Atlantic because the tradition of keeping church records came to America with the immigrants and was maintained as many families attended the same churches (or at least a church of the same denomination) for generations.

The late John T. Humphrey, who was one of this generation’s leading scholars of German family history, called church records “the ‘heart and soul’ of German genealogy.” While the civil registers described in chapter seven have assumed critical importance in present-day record keeping, most people will find that as they research events earlier than the last 150 years, the “glue” that holds together their generations of German ancestors will be found in church register entries.

The Protestant Reformation of the early 1500s was the advent of church registers in German States. Lutheran and Reformed clergy in German states that had rebelled against Catholicism used these registers to identify which people were on their side of the religious divide. When the Catholic church reacted with its Counter Reformation, a decree that came from the Council of Trent in 1563 mandated that Catholic priests keep registers of baptisms and marriages. Humphrey pointed out that these records were some of the very first documents to give named references to a large body of common people. As a result of this tethered political-religious environment, the registers of Lutheran, Reformed, and Catholic congregations have an overall consistency (and wealth) of genealogical information. These groups also supplied the first educated German-speaking clergymen in America, who played a crucial role in bringing this record-keeping tradition from the old world to the new.

Compared to America, Germany has relatively few Christian denominations with a historical or genealogical impact. While the political boundaries of the German states shifted a great deal over the centuries, the religious denominations remained fairly consistent, and one result that benefits genealogist is there are fewer differences between the types of church records kept.

Before the Protestant Reformation, the Roman Catholic Church simply was the only Christian church in the German states. While occasional heresies, often led by charismatic leaders, had flared up now and again in the millennium since Rome became the center of Western European Christendom, none of them were long-lasting with the exception of the relatively tiny group known as the Moravians, who will be profiled shortly.

Catholics believe in seven sacraments as visible rites of passage. While some of these are kept private, like the confessions to a priest that are a key part of the sacrament of penance, others such as baptisms and marriages are public acts for which records are ordinarily kept. Historically, Roman Catholic records were kept in the Latin language and as a result are often found a non-cursive handwriting that is considerably easier to decipher than German cursive script. About half of Germany’s present-day population is Catholic.

Germany’s largest Protestant group has been the Lutherans, who began when Martin Luther rejected many of the institutional practices of the Catholic church. After finding the hierarchy unreceptive to the wholesale changes he thought were necessary, Luther reluctantly separated from the Catholic church and the new denomination he formed was named for him; within a few decades of its founding, the denomination became an alternative to Catholicism as an official state religion. The German states that turned Lutheran were the first to mandate the keeping of church records for baptisms, marriages, and other events.

The second largest Protestant group historically was known as the Reformed. This group’s theology was guided first by Ulrich Zwingli of Zurich, Switzerland, and later John Calvin of Geneva, Switzerland. Zwingli made attempts to unify the Reformed movement with the Lutherans, but he and Luther could not reconcile their views of the Last Supper; Luther took the Catholic view that communion literally changed bread and wine into Jesus Christ’s body and blood while Zwingli said this sacrament was merely symbolic. The Reformed were a substantial “third force” among German denominations but didn’t gain international legal acceptance until the end of the Thirty Years’ War in 1648. Like the Lutherans, the Reformed kept records of baptisms, confirmations, marriages, and burials.

Most of the Protestant congregations today are called Evangelisch, stemming from the coerced “marriage” of the Lutheran and Reformed churches in the Preussen state in 1817. While this literally translates into English as “Evangelical,” it’s better just to think of the Evangelisch as mainstream German Protestants because they are neither a politically active nor particularly conservative group when compared to American evangelical Christians. The Evangelical Church in Germany consists of twenty-two mostly regional German churches. Some of these churches still bear the name of Lutheran or Reformed.

During the chaos of the early Reformation period, some people wanted to go much further than Luther and Zwingli by embracing complete pacifism and in turn rejecting involvement in the secular world. These Anabaptists (originally a pejorative nickname that meant “Re-baptism” because members of the group rejected infant baptism in favor of a believer’s baptism as an adult—which for the founders, all of whom had been baptized Catholic as infants, involved a second baptism) would have simply liked to have been left alone, but their beliefs were so radical that both Catholics and the emerging mainstream Protestants attacked them as a way of exterminating their beliefs.

A few German states tolerated Anabaptist groups (variously known as Mennonites, Amish, Church of the Brethren, and German Baptist Brethren) but most Anabaptists reacted to persecution by emigrating west to America in the 1700s or east to Russian areas in the 1800s (and then on to North America). Because of the persecutions, the Anabaptist groups kept few records of their existence while in Europe, and this lack of a record-keeping tradition did not change in America. Where Anabaptists are mentioned in records, it’s often because a particular German state had mandated that members of the sect register their births in the established church’s (Catholic or Lutheran) baptismal book or because ministers noted the deaths of Anabaptists in the burial records.

Finally, the so-called Moravians, formally called Brüder-Unität (literally “Unity of Brothers”), is a group that descends theologically from John Hus, a fifteenth century priest who had the same views that Luther, Calvin, and Zwingli would later espouse (but Hus, who lived before the invention of a printing press and was therefore unable to disseminate his writings, was burned at the stake). Count Nicolaus von Zinzendorf made his estate Herrnhut in Sachsen (Saxony) a refuge for a revival of the Moravians in the early 1700s. An intensely missionary church, Moravians immigrated in groups to the Americas and founded churches across the colonies that kept many records, including a daybook or “diary” of the congregation that mentions not just Moravians but people from the surrounding community.

While there are a substantial number of finer record-keeping differences (some noted above and others elsewhere in the chapter), the volume of documents kept by Christian denominations of the German-speaking people breaks into two broad groupings: those that baptized infants and those that did not. Without judging any of the theology behind this split, in almost every case the larger number of genealogically useful records were kept by the groups who baptized infants such as the Catholics, Lutherans, Reformed, and Moravians. This also holds true even among the German-speaking religious groups that sprang up in America.

In genealogical research, there are four significant types of church records—baptisms, confirmations, marriages, and burials. All of these records mention personal names; they are dated (attaching the individual to a certain point in time); and usually there is a “generational connector” to another person.

Sample of church record written in a narrative format (first record book of Bern Reformed United Church of Christ, Bern Township, Berks County, Pennsylvania)

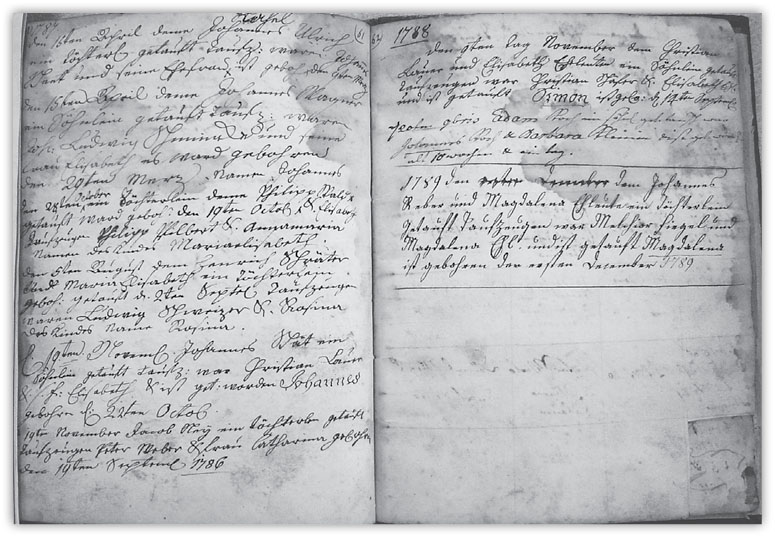

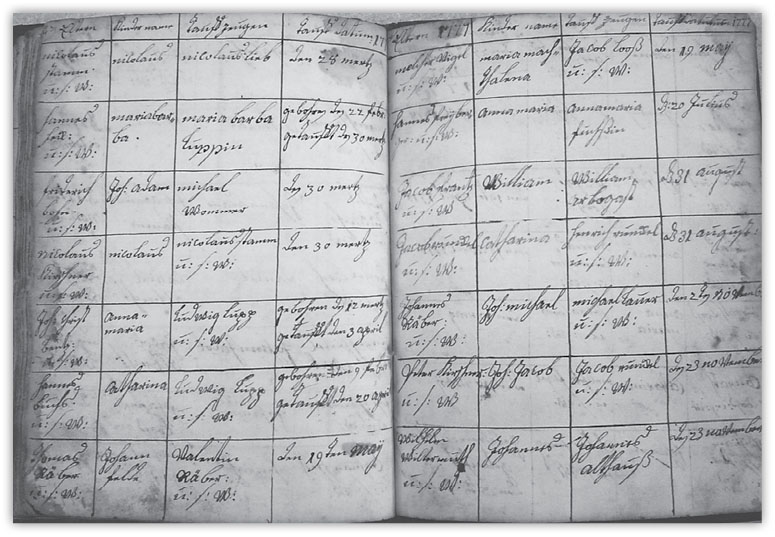

In format, some records (of all types) were written in a “narrative form” made up of sentences or phrases. The person writing out the record (usually, but not exclusively, a clergyman) also sometimes put the records in a “columnar” format with one column for each segment of information. Over time, more records were switched to a columnar format, sometimes with preprinted headings; in some pastors’ record books the entries took a narrative approach to filling in the columns, resulting in much information.

In some cases you’ll find the German clergy who created the record underlined or even noted in the margin the surname of the individual to whom the record primarily relates. Some enterprising clergymen even put together indexes for their records in the back of their register books, and while these can certainly be a shortcut, remember that the indexes are not likely to be perfect, so searching particular time periods of the records is recommended even when you have an index at your disposal.

In addition to the “big four,” we’ll also look at many other types of records (in most cases maintained by only a minority of churches) that might also be genealogically useful. In fact, whether it’s a church in America or Germany, make every attempt to locate every type of record that a church might have. Whether they’re the odd listing of “penances” for a German church or dry treasury reports kept by a congregation in America, you never know when your ancestor might be listed and what information you might gain.

Sample of church record written in a columnar format (first record book of Bern Reformed United Church of Christ, Bern Township, Berks County, Pennsylvania)

Infant baptisms are terrific substitute birth records. Catholic belief was that all people were born with original sin and that anyone who died unbaptized would be excluded from heaven. This created a race to the baptismal font. In Germany, children were baptized quickly, sometimes the same day they were born, and this tradition continued even among Protestants who didn’t have such an exclusionary view of heaven.

A typical baptismal record, called Taufschein in German, almost always includes:

In Germany, the baptism record often was the only time a person’s full name was used, as German children typically were referred to by a Rufname and their surnames throughout their lives. See chapter six for an explanation of Rufname.

The children were nearly always named for the sponsors; some records, in fact, do not list a name or sex for the child, but this information can be inferred from the name of the godparent. Grandparents, aunts, and uncles were often godparents; sometimes their relationship is explicitly noted in the record, but other times you’ll need to put together the whole family to figure out the connection.

The records usually give dates of both the birth and baptism (though if only one date is given, that is likely to be the baptismal date, not birth date, because the record is of the baptism). Sometimes the record even includes the exact time of birth. Other data points in the baptismal records can include the occupations of the child’s father and male sponsors as well as village of residence and citizenship status for the family.

A not uncommon occurrence is for pastors to “cross-reference” the baptismal entry to indicate the individual’s death; sometimes this is done merely by marking a cross on the entry while other times the date of death is also listed.

Sample marriage record from German church registry

Marriage records in Germany, usually called Trauung or Heiraten, celebrated the union of a man and his wife before God. In general, this record lists:

Some of the marriage records also include birthplaces for the bride or groom. For second and subsequent marriages, grooms would ordinarily be identified as a widower and women would be identified by their first names as the widow of the late husband, who was identified by his Rufname and surname.

Sometimes dates will appear in the record that show when the marriage was announced before the church congregation (usually for three Sundays before the actual event), which is called “marriage banns” (or proclamation) to allow anyone with an objection to the marriage time to come forward.

It’s important to read every word of the marriage record, even if it a more challenging narrative-style record. The German text will often include the word Nachgelassene (or an abbreviation such as Nachgel.), which means “the late,” indicating that the father was already deceased at the time of the wedding. This is a cue to check the burial register for the father’s burial record and it gives you a time frame to search in: The burial record must be dated earlier than the wedding record.

The amount of information in German burial records, usually called Tote or Gestorbenen, can vary from sparse to fairly detailed. The basic information given is:

Note that the record is for the date of burial and not the actual date of death. So keep in mind that burial records are “substitute” death records, though the assumption that the person was buried two or three days after death is nearly always safe (exceptions being times of war or plague).

Many burial records go further than the basics. It’s not uncommon for the person’s full age in years, months, and days to be included. The person’s village of residence and occupation are often included. Burial records of children who died young usually include the name of the father (in fact, sometimes only the father’s name is listed along with the words Söhnlein or Töchterlein, meaning “little son” or “little daughter”) and women’s burials ordinarily show them as the wife or widow along with the husband’s name. Some men’s burials also list their wife’s names. A few of the burial records go even further and give additional family data, such as the number of children or birthplace of the individual.

Sample church burial record written in a narrative format

Sample church burial record written in short form

In churches that practiced infant baptism, part of the ritual was a promise to raise the child and instruct him or her in the Christian faith. These same churches then required those children to be “confirmed” in a ritual that followed a period of religious instruction in their teenage years. Most of the time, confirmation (Konfirmationen) was also the first time that the individual would be allowed to take communion, and it marked his or her official entry into full membership in the congregation.

Confirmation records usually contain a bit less information than the baptisms, marriages, and burials. The name of the individual confirmed is included and sometimes the person’s age (in years) and the name of the confirmand’s father. Occasionally the recorder would make an additional note about the individual’s skills (“cannot read well”) or temperament (“a headstrong girl”). Where multiple villages were part of one parish, the confirmation records are often divided up by village, which gives the researcher additional residence information.

Confirmation records can supplement the baptismal records by giving a snapshot some thirteen to sixteen years later. In some cases where no baptism record can be found, the confirmation record chronologically will be the first document recording the individual’s life.

Some church records include family registers called Familienbücher (“family books”). These are primarily found in areas of southern Germany, particularly Baden and Württemberg. The books organize much of the information from the church records alphabetically by family. Typically, a single entry in a Familienbücher list three generations’ worth of information:

Most Familienbücher began in the second half of the 1700s. There was a primitive form of this record called a Seelenbuch (literally “register of souls”). Some of these are only lists of names, but others are organized by family group and have much of the same information as a Familienbuch.

Do not use a Familienbuch listing in place of actual church records. Familienbücher were compiled and recopied from the original records so there will be copying errors. And in some cases families were omitted entirely from these compilations.

Some pastors and priests maintained records of people who attended communion services. This is especially true in Protestant churches (and particularly in the German-speaking congregations in America) where communion was celebrated much less frequently than under the Roman Catholic Church.

These records list the names, sometimes separated by gender but other times organized by families. Sometimes “cross-outs” appear over names on the lists, which can be a indication that the person died or moved. Especially for the churches in America, these communion lists are de facto membership lists for those congregations in the 1700s and 1800s because few such records were otherwise kept.

The Germans have a great phrase for the records that don’t fit into any of the above categories: Verschiedene Akten (meaning “various, sundry, or miscellaneous” acts). Among the church records kept in Germany, occasionally you can find people who applied for forgiveness or “penance” (particularly, for instance, if they had lived together or even had children before getting married). You also might find a history of the congregation written at the beginning of the records that also lists of names of pastors or priests for a congregation.

All of the records mentioned in this chapter potentially can be found in records of German-immigrant churches in America, along with several other types of records including:

Membership lists and alms books are especially important in researching German Anabaptists because this group often did not keep many of the traditional church records. A number of the alms books are the only eighteenth-century church records that exist for some Mennonite congregations.

Church records involve many dates, so a short primer on calendar changes affecting Germans will help inform your research. The Roman Empire gave the world the Julian Calendar, which tries to match the Earth’s solar year (which is just a bit short of 365¼ days long). A normal year under this calendar consists of 365 days. Every fourth year an extra day (or leap day) is added to the end of February. Over time, the extra one-fourth of a day in every year shifted the calendar dates so they no longer aligned with the seasons (particularly the spring equinox, which was used in the calculation of a date for the important Christian Easter celebration) by an increasing number of days.

To remedy this problem, Roman Catholic Pope Gregory XIII made a decree in 1582 that changed the calendar. This decree immediately dropped ten days from the calendar to put it back in sync with the seasons. To prevent dates from drifting away from the seasons in the future, the decree omitted leap days from century years except those divisible by 400. Most nations and German states that were Catholic at the time quickly adopted the Gregorian calendar. Some of the Protestant German states adopted the Gregorian calendar during the 1600s (Preussen, for instance, came aboard in 1610), though some German holdouts waited until 1700 to introduce the calendar, and Great Britain and its colonies (including those in America) waited until 1752 to make the switch.

As an additional complication, until 1752, Britain had used March 25 as the date on which the numbering of the year changed, which leads to some records in America from this time period to give “double dates” with both years noted. (All the states of the Holy Roman Empire, whether Protestant or Catholic, began using January 1 as “New Year’s Day” by the end of the sixteenth century, so this is rarely a consideration in German records.)

The website TimeandDate.com <www.timeanddate.com/calendar/julian-gregorian-switch.html> gives additional explanation on these calendar changes and shows the years before and after the switch from the Julian to the Gregorian calendar so you can see what days of the week certain dates fell on.

Until recently you had only two options for accessing German church records: If they had been microfilmed by the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints’ Family History Library (FHL), you could access the records through the library’s system <familysearch.org/catalog-search>. If they hadn’t been microfilmed, you used postal correspondence to contact the custodians of the original records in Germany and hoped that they made the effort to respond to you in a timely fashion.

One of the great myths that beginners often bring to German genealogy is the belief that the extensive Allied bombing of Germany during World War II caused a significant loss of church records. It’s true that some church records were lost, most prominently those from the old Kingdom of Sachsen. But, by and large, most German church books either were safely protected or already had been copied in duplicate and sent to archives, or survived due to a healthy dose of luck. So courteously challenge anyone who tells you that the records were lost in World War II bombing raids.

However, while World War II had little impact on the survival of church records, earlier wars did have an impact. In some areas, no records survive that date earlier than the end of the Thirty Years’ War (1618–1648). The parts of southwestern Germany that suffered French invasions in the late 1600s sometimes do not have record books that predate the beginning of the 1700s. Many parts of Preussen, especially the eastern sections now mostly belonging to present-day Poland, were sparsely settled until the early 1700s, and as a result records for that area don’t begin until that time. Baptisms were usually the first registers to be kept.

Matricula-Church Registers Online is using a European Union grant to digitize German-language church books and make them available free online at <www.matricula-online.eu>. Most of Matricula’s current record holdings are for the Bavarian Roman Catholic Diocese of Passau.

The FHL has microfilmed many German church records, and an increasing number of these records are available in some form on the FamilySearch website <familysearch.org>. FamilySearch is digitizing the microfilm holdings at an ever-increasing rate and posting those scanned images of the records online. FamilySearch volunteers are abstracting and indexing some of these records to post on the website. This is in addition to the many German church record abstracts that have been available for years in FamilySearch’s master database, primarily because of an “extraction program” for baptisms and marriages done for the International Genealogical Index. FamilySearch has enough of the German church books available online to make <familysearch.org> your first option for accessing the records. You can access the records on <familysearch.org> in a variety of ways:

Option 1: Search all FamilySearch databases by clicking on the “Search” tab and filling in a name of interest (as well as place and date information, if you have them).

Option 2: Search a specific database on the site by clicking on “Search” and then “Catalog” (from menu of tabs at the top of the “Search” page). “Catalog” refers to the FHL catalog, the computerized card catalog for all the holdings in the FHL. Here you can fill in a village’s place name, a surname, title, or author to track down holdings that might be relevant. To find digitized records that are available for viewing on <familysearch.org> click the Continental Europe link on the Search page, then click the country name you are researching.

Most German villages are found in the catalog under their jurisdictions during the Second German Empire from 1871 to 1918. For instance, the town of Elsoff, which for most of its history was part of the small but independent Graftschaft (countship) of Wittgenstein, is found in the catalog under “Germany, Preussen, Westfalen, Elsoff”—Preussen being the German word for Prussia and Westfalen used because Wittgenstein was made part of Prussia’s Westfalen (spelled Westphalia in English) province as a result of the settlement at the Congress of Vienna.

You can use the Meyers Gazetteer (see chapter five) to learn if the town you are researching is a Kirchdorf (a village having a church), but the gazetteer won’t tell you to which parish that village belongs. However, the FHL has volumes it calls “church record inventories” that list the villages from particular German states, to which parishes they belong, and what church records exist. These inventories include both records that the FHL has microfilmed as well as records that are not microfilmed.

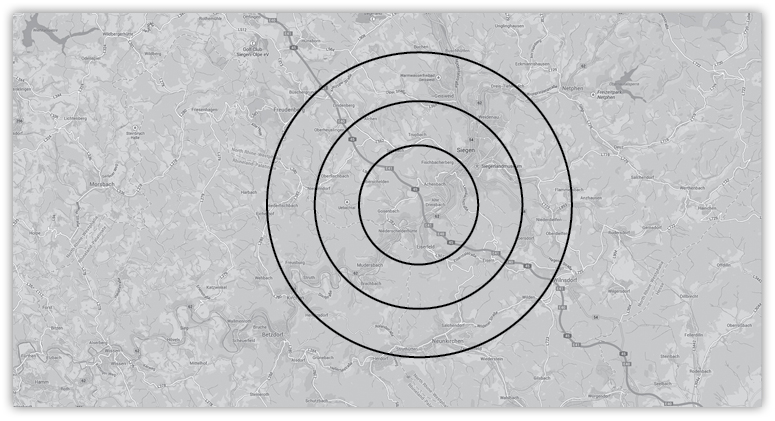

This graphic illustrates the concentric circles research strategy. Start with your suspected Heimat and expand your research radius outward until you find the records you seek.

Of course larger German cities have multiple churches. Naturally, your first strategy when you have an urban German ancestor is to be particularly meticulous in examining the American record of the immigrant to see if any record about him or her reveals a church name. Failing that, you need to try and find an exact address in Germany for your immigrant, use the maps of the cities in Meyers Gazetteer to find the closest church of the correct denomination to that address, and look at those records. Finally, examining all the city churches’ records from the relevant time period may be your last resort.

Realize, too, that parish boundaries were not static throughout the chaotic history of the German states. Sometimes as particular towns grew, they were detached into their own parishes. This is why the book series Map Guide to German Parish Registers should be used with caution because it shows Catholic and what it calls “Lutheran” parishes during one particular time frame, which may not be accurate for the time period in which you’re working.

If other strategies fail you, use what’s called the “concentric circles” methodology. This involves starting with the village that you believe was the Heimat of your ancestor. If that search doesn’t give you the results you need, draw a circle with a five-kilometer radius around the village and research all of the towns that fall within that circle. If those towns don’t have your ancestor, expand your circle so it’s now ten kilometers in radius from the suspected Heimat and research the villages that fall in this larger circle. This will ensure that you cover all the records within a given geographic region. Either you’ll hit pay dirt or go back to the “hypothetical drawing board” and increase the radius of your research circle.

If nothing shows in the digitized holdings, you might have to search the actual microfilms. You can find a complete listing of the microfilms online at <familysearch.org/catalog-search> and have the films you need delivered to a Family History Center near you (find locations at <familysearch.org/locations/centerlocator>) for a nominal rental fee. There is a delay while the film is being delivered to the Family History Center. You also can search the complete microfilm collection at the FHL in Salt Lake City.

Most of the microfilms are good representations of the originals. Occasionally, however, you may encounter a readability issue, especially if the originals are filled with smears or inks that bled through from one side of the page to the other. Some of the cataloging done of the film is faulty; be skeptical of the dates included in the records as you scroll through the microfilm because the dates are sometimes inaccurate (for instance, the cataloging for a particular town’s church records may say “Taufen, 1702-1765” and when you look at the records you see that the baptisms indeed begin in 1702 but skip from 1705 to 1730 before concluding with those from 1731 to 1765). In some record books, the right-hand pages were used first and then the left-hand ones are filled from “back to front” meaning only right-hand pages were written on until the writer reached the final page in the book, at which point he began writing on left-hand pages starting with the last left-hand page in the book and working his way up to the first left-hand page in the book.

Finally, some of the microfilms will be called Kirchenbuchduplikat (meaning “church book duplicates”), and these refer to handwritten copies of the original records. These were usually created because a state church required them. This “spare set” helped cut down on record loss. Another benefit is that the script in which the duplicates are written is usually much more legible. The drawback is that because these duplicates are recopied, many times at a date much later than when the originals were produced, the duplicates suffer from the same sort of copying mistakes you can expect from any secondary source. In addition to formally created duplicates, you’ll also find microfilms for informal partial duplicates (probably created by pastors seeking to rewrite the records for better legibility) that were started but never finished.

There are some church records that have neither been digitized nor microfilmed. In this case, you’ll need to write directly to the parish pastor to enquire if the church has records available and if a search of the records can be attempted. Example query letters written in German are included in the appendices to help you make your request. If this is a route you must take, the key to success is to not be overwhelming in your initial request. First impressions, as with anything, are very important. If the local official indicates that the original records have been moved to a religious archives (or if the archives has microfilmed the records independently of the FHL system), you’ll need to contact the archives. Use the same tact and discretion you used when initially writing to the local parish.

To effectively use German church records, you often need to use a “zigzag” pattern in which you use the pieces of information in one record, the father’s names in marriages for instance, as a jumping-off point to another set of records, for instance baptisms, which will yield the mother’s name and a birthdate for the ancestor, and then use the father’s and mother’s name to search for the marriage record in the previous generation. Repeat this pattern with each generation.

The good news is that nearly all of the early church registers of German groups in America have been translated and published. For those that have not been translated and published, the originals generally can be found either with the original congregations or in denominational archives. The bad news is that many of the published translations are faulty. Also take special care to find out whether all the records of a particular congregation are part of the translation; in some cases, only the baptisms were published even though other records ranging from marriages to communion lists might also exist.

The records of the German-dominated churches in America have many of the same consistent features that make those from Germany so valuable. In many cases, records for German immigrant churches in America can give clues needed to help identify the immigrant’s village of origin. To give a few scenarios from American church books: A baptism may indicate that the family recently arrived; marriages may give the names of parents as well as village names in Germany; a burial could also contain an exact birth date that can be matched with the date from a baptismal record in a German church register.

Of course, there were also different circumstances in America that create differences between German and American records. As noted in chapter two, there was a shortage of ordained clergy in America and as a result, the German-speaking people often turned to others, including tradesmen at times, for leadership of their congregations. Some of these men were less educated than others and at times that reflected in the quality of their handwriting and quantity of their record keeping. The shortage also resulted in pastors who “rode the circuit” to serve many churches, and sometimes they did not diligently separate the baptisms, marriages, and burials they were recording into separate registers for each congregation; while nearly every congregation kept its own baptismal book, sometimes one particular congregation served as the “seat” of the parish (or charge, as the Reformed called a group of congregations that shared a pastor) and records of marriages and burials for all the parish congregations were entered in its register.

The shortage of clergy in America also impacted families who needed pastoral services when no minister of their denomination was available to perform the baptism, marriage, or burial. Among the Lutheran and Reformed, it was not unusual for families to “cross over” and not worry about the theological fine points when, for instance, a sick baby needed to be baptized or a funeral needed to take place. In the latter type of situation, reference to a burial in a graveyard half a county away might be made in a church’s records.

Another idiosyncrasy that developed was the concept of a “union church,” in which two or more congregations of different denominations shared the same building, following a precedent they’d seen in Germany where church buildings were sometimes shared among denominations in the more tolerant German states. These union churches were found mostly in America’s Mid-Atlantic region and in these cases there is even more potential for finding records of a family in a denomination not their own (some union churches even kept all their pastoral acts together for a time).

Especially in rural areas of the “first wave” immigration, German continued to be spoken in the pulpit and used in records well into the nineteenth century. In fact, many of these areas only turned away from the use of German as a result of World War I and misplaced patriotism that sought to suppress “German-ness” in America.

In the more diverse religious atmosphere of America, some Germans from the mainstream Lutheran and Reformed groups drifted away to form groups that weren’t quite as radical as Anabaptists but had some similar beliefs, including the rejection of infant baptism. Two of these groups, the Evangelical Association and the United Brethren in Christ, today are part of the United Methodist denomination. These groups follow the general rule of thumb about denominations that practiced adult baptism—their church records provide little genealogical information.

The German Lutheran churches in America split, too, as a conservative faction called the Missouri Synod Lutherans gained sway in the Midwest (they retained infant baptism, however). Many of the “second wave” Germans came after Preussen’s forced merger of Lutherans and Reformed; these immigrants kept the English form of Evangelisch for their churches, and in 1934, merged with the “first wave” Reformed to become the Evangelical and Reformed Church. In 1957, this group merged with the Congregationalists from New England to form the United Church of Christ.