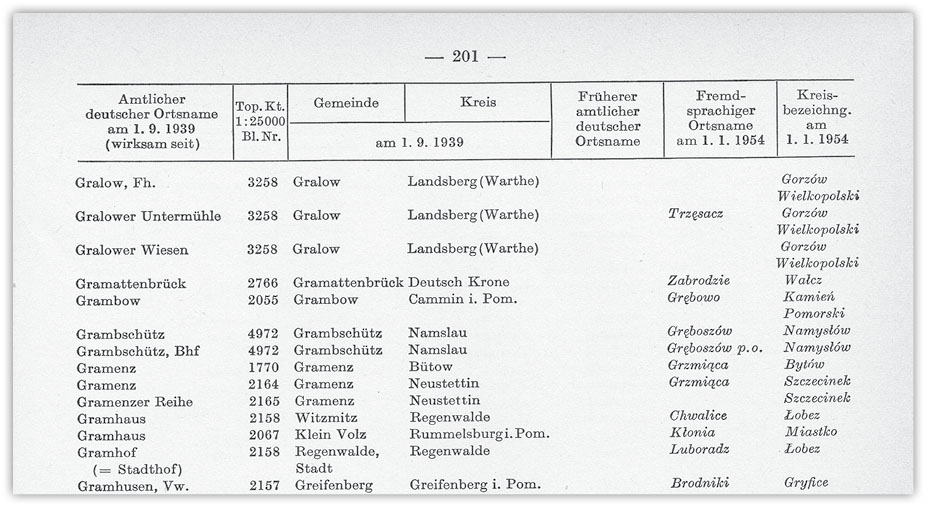

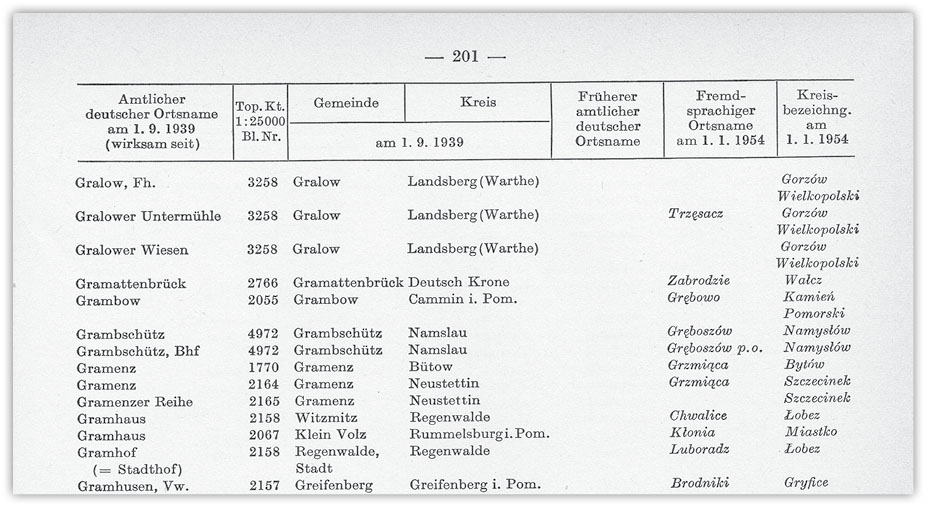

Entries in the Amtliches Gemeinde — und Ortsnamenverzeichnis der Deutschen Ostgebiete unter Fremder Verwaltung (“Official Communities and Place Name Index of Areas in the German East Now Under Foreign Administration”)

As we discussed in chapter one, time and place are two important cross hairs that help you target your family history research. Chapter three outlines many of the ways to determine an immigrant ancestor’s village of origin—setting up your first cross hair, place. Chapter four gives a detailed history of Germany, helping you better understand and establish your second cross hair, time. This chapter explores the geography of Germany to help you continue homing in on the right place to research. It includes an overview of the current German governmental and archives structure, and identifies key resources that will help you find the repositories that have the records you need.

When you identify the village of origin for a German ancestor, you may discover many similarities between the old country and the New World places in which your ancestor resided. You’re likely to find plenty of “precedents” in terms of geography, topography, and social organization when you shift your research focus to across the Atlantic Ocean.

After all, it’s only natural that German-speaking people would want to look for places that reminded them of home, even if many other circumstances in America were different. You will notice one big contrast between German farms and American farms: In rural areas of Germany, farmers built their houses in a village setting and owned noncontiguous strips of land surrounding the village on which to keep their crops and livestock. In rural areas of America, these same types of farmers built their homes on their farmland and relatively fewer people lived in a village environment.

While Germany is a scenic nation with much natural beauty, it’s useful to remember that its current boundaries (which total 137,846 square miles) would fit within the U.S. state of Montana (though Germany’s dense population is about seventy times as large as that state’s!). Even at its largest extent before World War I, Germany’s area checked in at 208,826 square miles, smaller than Texas.

As a mark of German influence on Europe, virtually all of the nation’s neighboring states either have or had German-speaking sections:

Compared to the United States, Germany today is an ethnically homogenous nation. More than four-fifths of the 82 million people are German, and the largest non-European ethnic group are people from Turkey, who started to arrive a couple of decades ago as guest workers to augment the aging German workforce. Turks make up just 4 percent of the German population.

Germany’s physical geography begins with the Northern European Plain that covers about a third of the country from its shores on the North and Baltic Seas, then rises into hilly areas with many remaining forests that comprise the central part of the country (cut in the west by the river valleys of the Rhine and its tributaries). Finally, the very southern and eastern borders feature true mountains such as several iterations of the Alps as well as the Ore Mountains on the border with the Czech Republic.

Two of Europe’s most storied rivers, the Rhine and Danube, both flow through considerable portions of Germany. The Rhine River forms part of the border between Germany and France and then goes through Germany’s industrial heartland area before leaving the country for its eventual mouth in the Netherlands. The Danube rises in the state of Baden-Württemberg and flows east through Bavaria before crossing into Austria. Other major rivers—the Elbe, Ems, Weser, and Oder—also flow primarily through German territory. With the exception of the Danube, nearly all of Germany’s major rivers flow north, which spurred the building of east-west transportation arteries such as canals and railroads in the nineteenth century.

Despite a much higher population density (Germany has about six hundred people per square mile; the United States has less than one hundred people per square mile), the land of Germany does not seem “crowded” outside of few very large cities (Berlin, Hamburg, Munich, Cologne, Frankfurt and the Rhine River megapolis that includes Düsseldorf, Dortmund and Essen). This is due, in part, to the strict regulations Germany has put into place to prevent “urban sprawl.”

Today, Germany’s political structure is that of a federal republic, formed as West Germany in 1949. The the formerly Communist-bloc East Germany was added to the republic in 1990. The republic is divided into sixteen Länder (singular, Land), the political equivalent of a state in the United States. Three of these Länder are independent cities—Berlin, Bremen, and Hamburg. Many of the states are nonhistorical amalgamations of areas that had never before shared a government, such as Baden-Württemberg. Others (such as Nordrhein-Westfalen) include smaller areas (such as Nassau-Siegen and Wittgenstein) that had distinct identities apart from the Land to which they are now attached.

All of the Länder are divided into units called Landkreise (singular, Landkreis) or simply Kreise (singular, Kreis). A Kreis is at a level similar to a county in the United States (the word is also translated as “district”). The Kreise, in turn, are made up of Gemeinden (singular Gemeinde), which are more or less equivalent to American townships, though the word would be more properly translated as “community” in the civil sense or “parish” when it refers to a religious subdivision.

Some of the Länder have an additional administrative unit called a Regierungsbezirk, which might be thought of as a “super-county.” The unit has no current genealogical significance other than sometimes the territories assigned to particular civil archives go by these boundaries. Likewise, there are collections of municipalities with names such as Verbandsgemeinde that exist today but do not have an impact on records; many Verbandsgemeinde came about during a major reorganization and consolidation of German municipalities that occurred in 1974, which also resulted in many smaller villages being attached to larger nearby cities.

So, which of these German divisions of government are useful for the family historian? It’s important to remember that in Germany there’s no centralized system for record keeping. There is a German Federal Archives (called the Bundesarchiv). This archive is housed in the city of Koblenz, and there are a number of specialized branches throughout Germany. While about half of the archive’s holdings were destroyed in World War II, many military records remain from the second half of the nineteenth century through the mid-twentieth century, and the archives has made more than 100,000 photographs from its holdings available to the public through Wikimedia Commons <commons.wikimedia.org>.

The Bundesarchiv also holds the records of the Supreme Court of the Holy Roman Empire (known in German as the Reichskammergericht), which was founded in 1495. This court settled disputes between citizens of different states from around the empire and even heard suits between lords and their subjects. (An interesting footnote is that the Reichskammergericht was infamous for its ponderous deliberations … in some cases it took more than a century to reach a decision!)

Each German state has at least one archive; some of the “amalgamated” Länder have more than one. These state archives go by different names—Landesarchiv (national archives), Landeshauptarchiv (state archives), or Generallandesarchiv (general state archives)—but all are repositories with varying amounts of everything from church records and civil registrations to military, court, and land records.

The major religious groups in the German states—Roman Catholic, Evangelisch (the Protestant denomination resulting from the forced union of Lutheran and Reformed congregations within Preussen in the early 1800s), Old Lutheran, and Moravian (called Herrnhuter in German)—also have their own archives. Many of the congregational registers from these religious groups have been microfilmed by the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints’ Family History Library (FHL) <familysearch.org>, and most congregations still keep their original records. However, in many areas Kirchenbuchduplikat (“duplicate church books” that are recopied versions of the originals) are found in these church archives. A listing of the contact information for state and church archives in Germany appears in the appendices of this book.

On Germany’s local level, the cities and villages (in many cases each still being its own Gemeinde or community) often contain four different potential sources of genealogical information.

1. CITY ARCHIVES: The first potential source is the city archives (Stadtarchiv or Gemeindearchiv), which contain records of local government papers. These archives could contain everything from fifteenth-century tax lists to land records to guild registers.

2. ON-SITE CHURCH RECORDS: The second potential source is visiting an actual church. German churches will often have their original records on-site. Access often depends, once again, on planning as well as showing that you are prepared to carefully inspect the records without damaging them.

3. LOCAL HISTORICAL SOCIETY OR MUSEUM. A third potential source is the local or village historical association or museum. These are usually shoestring operations made up of individuals with expertise in the genealogy of the families from that place. Once again you’ll need to plan ahead of time to coordinate with the often-sparing “as needed” hours.

4. CIVIL REGISTRATION OFFICE: Finally, the local civil registration office (known as a Standesamt) is where the birth, marriage, and death records are kept. There is no particular “retention schedule” before these records are passed on from the local level to state level, so often the local office will have records that date all the way back to the initiation of the record-keeping system.

There are also many nongovernment repositories with collections of records that can help genealogists. Many are listed in the appendices to this book. A couple that are especially worthy of note are the Institut für pfälzische Geschichte und Volkskunde (Institute for Palatinate History and Folklife Studies) in the city of Kaiserslautern and the Deutsche Zentralstelle für Genealogie (German Center for Genealogy) in Leipzig, both of which have large card files with genealogical information on individuals.

In addition to understanding the current governmental and archives structure in Germany, you’ll need some historical background to help you bridge the gap between the Germany of today and the German states of your ancestors so you can find the information you seek.

The modern-day subdivisions of the German government are Land, Kreis, and Gemeinde (roughly equivalent to state, county, and township). As you learned in chapter four, the boundaries and ruling authorities of the German states were fluid for most of history. This means there are historical government divisions and subdivisions that don’t exist today, but may have impacted your ancestor. The following chart includes the names and definitions of historical subdivisions. You’ll want to keep going back to your trusty cross hairs—“time and place”—to get a sense of whether and how these words and phrases might affect your search for records. In many cases, they may not have an impact.

A rundown of possible terminology appears in the “German Names for Government Divisions” sidebar. Illustrations from a few German states will be used to show some of the complexities.

Gerhard Köbler’s book Historisches Lexikon der Deutschen Länder is an invaluable reference work for detailing many of the dynastic shifts that were the underpinnings for these changes in local government terminology. Another helpful book is Ancestors in German Archives by Raymond S. Wright, III, which includes summaries of the many historical archives in Germany, including those kept by the nobles of the smaller German states.

On the religious side, the most important level is the parish or Gemeinde, though it can be useful to know further hierarchies, especially among the Roman Catholics, whose parishes were all part of a diocese or archdiocese. Protestant churches generally were not as hierarchical though in some areas would have been responsible to the state church run by a bishop or board. Kevan M. Hansen’s continuing Map Guide to German Parish Registers series can be helpful, though he does not always appear to understand or properly differentiate between the historical Protestant groups.

Chapter three outlines many of the ways to determine an immigrant ancestor’s village of origin. After the village has been established (or a tentative hypothesis about the village has been formed), the researcher’s goal is to find that historical village (or city) on a modern map. When you locate the village, you will be able to put it in its current and historical contexts, which will help you learn more about your ancestor’s life and identify where pertinent records might be found.

There are a number of factors that can affect how quickly you can locate the village of origin on a current map. The two most important factors are the clarity of the place name in historical records (chapter three describes some of the ways that place names can become garbled; chapter six gives further detail on German phonetics) and how common the particular place name is in Germany (for example, think of how many U.S. states contain a city called Springfield or Columbus).

The simplest approach to finding the village is doing a Google Maps <maps.google.com> search. But because so many German towns have identical or similar names, you want to be cautious that you’ve found the “right” town by that name … even (actually, especially!) if Google seems to show only one town with such a name.

The longer, but more accurate, method consists of a number of steps, which you will still want to follow even if you’ve been able to find the location of the village with Google Maps. Why take the extra steps? Because to find actual records about your ancestor, you need to determine whether the village is one that has its own register’s office (for vital records) and the seat of a church parish (for church records) or whether these records will be found in a larger nearby town or village.

In brief, the steps for locating the village of origin on a modern map consist of:

Meyers Gazetteer (also called Meyers Orts) is short for Meyers Orts- und Verkehrs-Lexikon des Deutschen Reichs (literally translated as “Meyers Geographical and Commercial Gazetteer of the German Empire”). It’s essentially a “place name encyclopedia.” The 1912–1913 edition contains some 210,000 entries for the cities, villages, hamlets, noble estates, farms, mills, and forest houses. (It’s worth noting that other gazetteers exist. One example is Neumanns Orts- und Verkehrs-Lexikon des Deutschen Reichs published in 1905 and available at the Library of Congress in Washington, DC. Neumanns does have some additional historical notes on towns, but Meyers has more entries overall.)

Meyers Gazetteer is now most easily accessible as a free resource on the subscription website Ancestry.com <ancestry.com> (in the Card Catalog Titles, search for “Meyers Gazetteer”), but the FHL also has the gazetteer on microfilm, and some major genealogical libraries have available copies of a reprint with an English-language preface that was published in 2000.

Each entry in the Gazetteer consists of a heavily abbreviated list that includes the place’s location (including the name of the state or noble jurisdiction of the empire to which it belonged as well as which subdivision such as a Kreis or Provinz it is found within); whether it has certain government offices (or by which village’s offices it was served); transportation available (or proximity to railroads); population; communication such as post offices and telegraph; whether it has its own civil registry office (or what village’s office serves the town in question); existence of a church and parish seat; industries; and any dependent settlements.

As with all German books published during the Second German Empire, Meyers uses the hard-to-read Gothic font that will be considered in detail in chapter six. As noted, the lists are heavily abbreviated, so you’ll need some resources to help you understand them. How to Read & Understand Meyers Orts-und Verkhers-Lexikon des Deutshen Reichs by Wendy K. Uncapher is the most concise guide for deciphering the full gamut of information found in Meyers Gazetteer. The booklet includes a glossary showing the German words for many of the abbreviations found in Meyers as well English translations for those words. Uncapher also points out that a supplemental addendum to the Meyers Gazetteer called Erster Nachtrag (“first addendum”) was published in 1921. (Ancestry.com includes Erster Nachtrag in its searchable collection.) It contains many corrections and additions and for this reason Uncapher recommends researchers always consult Erster Nachtrag any time they use Meyers Gazetteer.

While it is worthwhile to become acquainted with all the information that can be gleaned from Meyers (it can answer, for instance, the question of “how big was the town from which my ancestor left?”), three segments of the information are especially crucial to family historians.

1. NOBLE JURISDICTION AND SUBDIVISION. Use the noble jurisdiction and subdivision of the village to winnow out the multiple place names. If your research has given you a village name but not the village’s German state, you initially may need to guess at which place is correct. Usually your research will give you clues, such as religion, to help you make a logical guess. (For example, if only one village of those with the same name has a Roman Catholic church and your ancestor was Catholic, try the village with the Catholic church first). You also might also have to consult a historical map such as Ravenstein’s Atlas (described later in this chapter) to help determine the correct village.

2. AVAILABILITY OF STANDESAMT. Standesamt means “civil registration office.” Meyers abbreviates this word as “StdA.” The importance of reading the punctuation correctly here is pivotal. If the StdA. abbreviation is followed by a comma or semicolon, then the village has its own civil registry office, and you’ll need to consult that office’s records for your ancestors’ civil vital records. If there’s no punctuation after StdA. the town name that follows the abbreviation contains the registry office that serves the village in question.

3. RELIGIOUS INFORMATION. Meyers indicates if the village had a Pfarrkirche (abbreviated “Pfk.”) or parish church. If there is a parish church in the village, you often can skip a couple of steps and move on to determining whether the church records for the parish in question exist and whether they’ve been microfilmed, digitized, or can be found only in their original form. If there is no indication that the village had a church or if the village is called a Kirchdorf (“village with a church”), the parish to which this village belonged was in another village; you’ll need at least one other step to find out the name of the village with the parish church.

The Meyers Gazetteer also contains maps and street indexes for major German cities. These cities will have many churches as well as civil registration offices so there are special strategies for finding ancestors who were urbanites in Germany which are outlined in chapters seven and eight.

For many people with German ancestry, the villages from which their immigrants left are no longer within the boundaries of present-day Germany, and these villages now often carry non-German names. Fortunately, that ever-present Teutonic thoroughness has created gazetteers that will help track down such villages.

TERRITORIES LOST AFTER WORLD WAR I. For the territories that Germany lost after World War I, the gazetteer to consult is Deutsche-Fremdsprachiges Ortsnamenverzeichnis (the “German-Foreign Place Name Index”), which was published in 1931. This gazetteer is broken down by the country to which Germany lost a particular area: France (Alsace-Lorraine), Belgium (the small Eupen-Malmedy region), Denmark (northern Schleswig), Lithuania (Memelland, which then became part of the Soviet Union for decades), and Poland (parts of Preussen, Posen, and Silesia). The listings start with the German name and give the new foreign language name and district (county or department) within the new country.

TERRITORIES LOST AFTER WORLD WAR II. Nearly all German territory ceded as a result of World War II went to Poland as that nation was shifted westward (the Soviet Union absorbed what had been the eastern parts of Poland and also took a small amount of East Preussen; a small amount of Silesia went to what is now Slovakia). The Amtliches Gemeinde—und Ortsnamenverzeichnis der Deutschen Ostgebiete unter Fremder Verwaltung (“Official Communities and Place Name Index of Areas in the German East Now Under Foreign Administration”) was published in 1955 as the top resource for these lost villages. As with the post-World War I guide, it starts with the German village name and then gives the new foreign-language name. (If the village cannot be found in Amtliches Gemeinde, there is an alternate called Müllers Grosses Deutsches Ortsbuch; Part II of that gazetteer covers the same area.)

TERRITORY CEDED TO POLAND. Because the boundaries of Polish counties changed, the county names in the above reference works may need a further “translation” using the Polish gazetteer Spis Miejscowósci Polskiej Rzeczpospolitej Ludowej to ensure you find the correct villages.

Entries in the Amtliches Gemeinde — und Ortsnamenverzeichnis der Deutschen Ostgebiete unter Fremder Verwaltung (“Official Communities and Place Name Index of Areas in the German East Now Under Foreign Administration”)

TERRITORY CEDED TO RUSSIA. East Preussen towns that went to Russia can be found in the report from the U.S. Office of Geography’s U.S.S.R. and Certain Neighboring Areas: Official Standard Names Approved by the U.S. Board on Geographic Names, which also gives latitude and longitude coordinates.

The Meyers Gazetteer helpfully steers genealogists to a civil registry office even when a particular village didn’t have one. Unfortunately, it’s not as helpful with villages that weren’t the seat of a religious parish or that didn’t have a church at all (thankfully, the latter case is rather rare).

Sometimes, you can use the FHL catalog (available online at <familysearch.org>) and find the right cross-reference for the village. But to do a thorough job, you’ll want to consult the geographically specialized gazetteers of the German Empire states. See the “German Gazetteers” sidebar for a listing of some specialized gazetteers. They can also be useful supplements to Meyers and can help verify the existence of village names that no longer appear on all but the most detailed maps. Another resource is the series Map Guide to German Parish Registers that will be talked about in more detail in chapter eight.

MICROFILMED AND DIGITIZED RECORDS. After you have identified the correct places to find records tied your ancestors’ village of origin you can search to see what records are available either digitally or on microfilm. The FHL has microfilmed many church registers and some civil records, and an increasing number of these microfilmed records are being digitized, indexed, or both for <familysearch.org>. More detail about these records, as well as how to go about accessing such records when they are not in the FHL system, is in chapters seven and eight.

While gazetteers are wonderful resources, you’ll also want to consult a number of maps or atlases—some modern-day, some historical—to put your ancestor’s village into more complete context.

RAVENSTEIN’S ATLAS. There are number of historical maps for portions or specific states of Germany, but the number-one map resource is known as Ravenstein’s Atlas (full name: Atlas des Deutschen Reichs by Ludwig Ravenstein). It’s a finely detailed map from 1883. The University of Wisconsin–Madison has scanned Ravenstein’s Atlas and placed it online along with detailed instructions for its use at <www.library.wisc.edu/etext/ravenstein>. While not every village appears in Ravenstein’s Atlas, the great majority are there. It gives researchers historical perspective on the Germany of more than a century ago, including some archaic spellings that were still in use at the time as well as showing villages that now have been absorbed by other towns and cities.

MODERN-DAY ATLASES. Modern-day atlases will help complete the picture for you, as well as provide you with the literal “road map” for a trip to Europe to bask in the glory of the Heimat that you’ve found. The most detailed atlas of present-day Germany is Der Grosse ADAC Jubiläums-Atlas Deutschland, which has a scale of 1:100,000. The Falk Maxiatlas Deutschland has a less-detailed scale at 1:150,000. The Strassen der aktuelle Auto-Atlas Deutschland carries a scale of just 1:250,000 but is more convenient to use than the larger atlases. The Polska Atlas Drogowy gives Poland in a 1:200,000 scale.

After you’ve firmly located the places—one village, multiple villages, offices for vital records; or one or more repositories—that you want to visit as part of a genealogical trip to Germany, putting together an itinerary is your next step. The best overall advice is probably to make no assumptions that traveling in Germany will be the same as a vacation in America.

Among the many contrasts is that gasoline is very expensive compared to America, usually running between two and three times the cost depending on currency exchange rates between the dollar and euro (while Germany’s relative compactness ameliorates this to some degree, cost-conscious travelers may wish to investigate rail transportation instead because it serves many German cities and medium-sized towns). For those who will rent vehicles for transportation, be advised that “standard” (stick-shift) transmissions are the norm in Germany; if you only drive automatic transmission, make sure you reserve a rental well in advance or be at the risk of not getting one at all. Also, be advised that some rental car companies still forbid their more expensive vehicles to be taken into the former Eastern Bloc countries. Getting a GPS device (request one in English) can also be helpful; you will need to obtain an international driver’s permit (available from auto clubs such as AAA), and it’s a good idea to bone up on international road signs.

For lodging, Germany’s version of a bed-and-breakfast is called a Gasthof or Pension and they are usually less expensive than chain hotels. Breakfast is generally included in the price even by hotels, although they usually will make available options with or without breakfast (“Mit Fruehstueck oder ohne Fruehstueck?” is the question the hotel clerk will ask—“With breakfast or without breakfast?”) It’s a good idea to have your first night’s stay reserved ahead of time, but those who want more flexibility in their trips often will just find a place once they stop for the evening for the duration of the trip.

Some of the smaller archives and Heimatmuseums (village museums) may be one-person operations, so contacting these places in advance is essential to ensure the location will be open. People at the village level usually are extraordinarily friendly to genealogy tourists, especially if they know that you have a connection to that particular town; more and more German towns have their own websites and links can be found on the town’s Wikipedia page. If the particular village does not have a website of its own, try contacting the tourism board for the town’s region; the tourism boards know that travelers will spend money, so they make it their mission to set you up with an archivist, local historian, or town officials.

Germany has a different electric system, so you will need electric converters and outlet adapters in which to plug your cell phone, computer, camera, and other devices (electrical outlets in Germany have round recesses, whereas U.S. outlets have square recesses).

Leave spare room in your suitcase when departing for souvenirs, gifts, books, and papers; notify your credit card company that you are traveling so charges are not rejected; and obtain duplicate prescriptions in case you lose or leave behind medications.

Travel in Germany has gotten substantially easier in the last two decades; ATMs are now plentiful and will allow you to make euro withdrawals (especially favored are accounts linked to a MasterCard). Cell phones, which once were on a different system, now for the most part work seamlessly (though you are advised to get a temporary international plan to avoid sky-high per-minute bills). Most Germans know at least a little bit of English (the exception: those in the former East Germany are more likely to have studied Russian as a second language) and they are almost always willing to make an honest effort to “meet you halfway” if you are trying to speak a bit of Deutsch.

Germany is still a nation filled with regional pride. For centuries they were Bavarians and Preussens; Württembergers and Wittgensteiners; Ostfrieslanders and Saxons; then and now, they are connected by the German language and national heroes such as Hermann and Charlemagne but also divided by dialects and generations stacked upon generations who lived in small independent states.

Just as it’s recommended to put together a chronology or time line of each of your ancestors to help fill in the gaps in his or her biography, you might well also put together such a time line relating to each village of interest. By plotting the events in that village during and after the time period your forebears lived there, it will lead you by natural consequence to what types of records are available and where they most likely will be found.