Chapter 3

Pinpointing the Place of Origin

To a fairly large extent, the goal of chapter two was to make your German-speaking ancestor distinctive so he or she stood out from the surrounding crowds. To put it another way, we collected data that makes this forebear a larger “needle” in the haystack of all ancestral possibilities.

But that often is just half of the equation: What about making the often-intimidating geographic “haystack” into a smaller mass? Attempting to pinpoint your ancestor’s exact place of origin can pay its dividends in research results. By “exact” we mean at the minimum determining the German-speaking sovereignty from which your ancestor emigrated, and, preferably, his or her actual village of origin.

NARROWING THE FIELD

You’ll get an exhaustive primer on German history and geography in the next two chapters of this book, but for now we’ll arm you with some of the basics so you understand why merely finding out that an immigrant was from “Germany” (or even slightly narrowed to “Preussen”), the largest of the nineteenth-century German states, isn’t enormously helpful information.

Once again you’ll need to line up those “time and place” cross hairs in order to make best use of the information that you find about a potential state, parish, or town of origin. There have been thousands of German microstates in the centuries since significant emigration began. The types of records that exist depends upon the locality. There simply is no central repository of records in Germany, and unfortunately, during the period when most immigrants left, there was no set standard of what records were kept and preserved.

For example, some areas were strictly Roman Catholic (resulting in no Protestant church records) while others had multiple religious groups and therefore several sets of records that may have survived (all of which might have parish boundaries that include different groupings of villages). Likewise, some areas of Germany had strong craft guilds that passed down trades from father to son (and recorded that fact). Tax records and certain types of court records will differ from one microstate to another; and because villages may have shifted from one microstate to another a number of times, you might find the same type of records from different time periods in separate archives. If it sounds complicated, it’s because it is. Complicated, however, does not mean unsolvable!

BEST SOURCES FOR FINDING VILLAGE NAMES

In chapter two we took you through the types of records most likely to show that your ancestor was an immigrant. In some cases, those records of passenger arrivals, naturalizations, embarkation, and censuses will also give you more than just the fact of immigration or something unspecific such as “Germany” for the immigrant’s birthplace. But more than likely you’ll need to research some or all of the types of the following records to find actual village names. And, as noted in chapter two, any record you come across should be examined for clues—even postmarks of letters sent from German relatives have helped find villages of origin!

Start with Home Sources

You were introduced to home sources in chapter one and hopefully have already taken the time to rummage through an attic or two in search of family Bibles, scrapbooks, newspaper clippings, and the like. Pay close attention to these items for immigration information or clues, and be careful not to dismiss items that may be more difficult to understand, especially documents written in German, such as letters from relatives or other writings that may look like scrap paper. If you can’t read German, hold on to these items until you tackle our primer on the German language (chapter six) and either test your skills or find a translator.

Among the home sources, you may find family Bibles or nonofficial private keepsake certificates of birth, confirmation, or marriage. Many German-speaking families had these types of records created to mark rites of passage; some received a family Bible upon marriage, and these Bibles often had charts and blanks to record family information. People could fill in these blanks themselves or take them to a professional scrivener for completion. (Blanks filled in by family members at the time of the event tend to be more accurate with the dates than those filled in by a scrivener at a later date.)

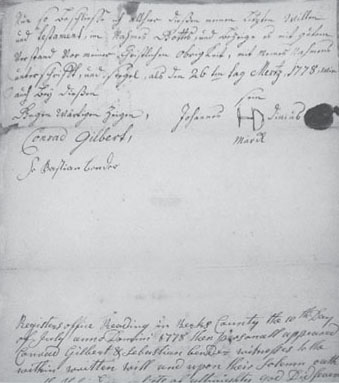

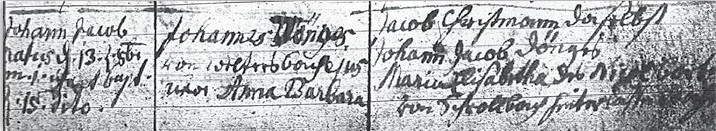

Decorative keepsake papers known as Fraktur (short for Frakturschriften, which literally means “broken writing” in German because each letter is inked without connecting to another letter) have survived in many families. These papers usually mark a birth (or baptism or both), a confirmation, or a marriage. The most common type of these records is a baptismal certificate known as a Taufschein. In addition to being found as a home source, these Fraktur have become collectible as pieces of folk art, and those that have passed out of families may be found in many local historical societies, quite a few of which have, in turn, published art books containing samples of these certificates.

The production of these Fraktur began during the “first wave” (following just a few German predecessor formats that were brought across the Atlantic) and continued well into the nineteenth century. Before the end of the 1700s, printers began selling templates that Fraktur artists or family members would then decorate and infill. Some churches even bought the printed templates for the pastors to infill with baptismal, confirmation, or marriage information.

Look at Internet Sources

The Internet holds an array of possibilities for finding your immigrant’s village of origin, and the list starts with the two super-heavyweights of the online genealogical world, Ancestry.com <ancestry.com> and FamilySearch <familysearch.org>. Ancestry.com, currently the world’s largest subscription database, has plenty of records to assist genealogists seeking German-speaking ancestors. Their catalog includes many of the record types mentioned in chapter two and in the following sections of this chapter—passenger lists, U.S. censuses, naturalizations, the Hamburg embarkation lists, vital records, obituaries, and much more. Ancestry.com also has German-specific records including the Württemberg Emigration Lists that track thousands who applied to leave the German state of Württemberg and the Germans to America volumes that are extracts of passenger lists where at least half the people aboard were German (some of these items come only with Ancestry.com’s international subscription package).

FamilySearch <www.familysearch.org> is free to all researchers and is rapidly expanding its reach to include images of many of the documents it has on microfilm, including German church records, though the percentage of these records that has been digitized is still relatively small. The FamilySearch site has evolved over the last decade and is now easier than ever for genealogical novices to use, but the beginner-friendly approach has buried some good tools that previously were more accessible. One example: FamilySearch’s International Genealogical Index (IGI) is a database of more than 600 million birth and marriage records, many of which were abstracted from German church registers. While FamilySearch’s homepage search will find a “direct hit” for your ancestor across any of the FamilySearch collections, an additional use of the IGI (because it is so heavy with German church record abstractions) is to enter just the surname for which you’re looking and see which villages have concentrations of that surname.

Of course, there are many, many other websites that may tie your immigrant to a village. Type your ancestor’s name in a general search engine like <google.com> or <bing.com> and see what comes up. Many of the present-day German states also have emigrant databases that you will wish to consult (these are listed in the appendices), especially if your proof of immigration is suggesting one particular German state as the origin. An example: The website Auswanderung aus Südwestdeutschland (“Emigrants from Southwest Germany”) <www.auswanderer-bw.de> has a database of nineteenth- and early twentieth-century emigrants from the present-day German state of Baden-Württemberg and includes the former territories of Hohenzollern in addition to Baden and Württemberg.

Published Compilations

There are several types of published works that may help you find immigrant origins. You’ll recall from chapter one that we call these “secondary sources” because they take primary or original information and essentially repackage it. Given the ubiquity of German immigrants’ descendants in America, many repositories—ranging from public libraries to county historical and genealogical libraries—have good collections of published books listing immigrants. Google Books <books.google.com>, Abe Books <abebooks.com>, eBay <ebay.com> and WorldCat <worldcat.org> also are great places to search for the published compilations described in this section.

Try to find family history books concentrating on a particular surname or descendants of a particular individual or couple (oftentimes an immigrant). Some of these histories are well-sourced and created with integrity, but others have very little source material. Use these histories as a starting point for your research and find primary sources to either prove or disprove the information.

County or locality histories are another possibility. Most of these were published in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, and their content is largely biographical sketches of area residents. These biographies often contain incorrect information because they were gathered directly from the subjects and never verified with primary sources. Even though names may be corrupted and generations are often skipped, these histories can be a useful starting point and occasionally list an accurate immigrant origin. Try taking a “whole-family genealogy” approach when searching for published histories. These books may contain the biography of a distant cousin who shares the same immigrant ancestor as you. This is especially true for descendents of “first boat” families where subject of the biographical sketch will be generations removed from immigration. Check with county historical societies or genealogy societies for a list of published histories for their area.

You can also find books that take primary source German records that identify village origins or match together German and American primary data to tie together an immigrant with his Heimat. Retired University of Pennsylvania professor Don Yoder was the godfather of these types of books; he had many connections to German genealogists and leveraged those relationships into compiling data of emigrants found in German archives, newspaper advertisements for heirs, and notations in church books.

Researchers Henry Z. Jones, Jr. and Annette K. Burgert each compiled a set of books that dovetailed primary sources such as church, land, and ship records from both sides of the ocean to identify the village origins of thousands of eighteenth-century German-speaking immigrants. Jones has concentrated on the 1709 Palatine group in six volumes, while Burgert has published more than a dozen books targeting either single or geographically contiguous villages in southwestern Germany. Werner Hacker meticulously abstracted thousands of references to emigration from many of the archives in German states and matched them up with limited American data and published his work.

Because of the much larger numbers of “second boat” German-speaking immigrants, a different type of database-in-a-book was attempted. This was the Germans to America volumes that still dot many library bookshelves, but are also available to search online as part of subscription to <ancestry.com>.

Unpublished Compilations

You can find many helpful records on the Internet, but not all records are online, let alone digitized. Even in the twenty-first century, there are times when you will need to visit record repositories and flip through actual papers to get the information you seek. One great resource that you’ll find only in paper form is the “Palatine Emigrant Index,” which consists of thousands of index cards that reference records from both sides of the ocean in an attempt to show where emigrants came from and went to. These cards are housed at the Institut für Pfälzische Geschichte und Volkskunde (Institute of Palatinate History and Folklore), previously known as the Heimatstelle Pfalz (Palatinate Home Office) in Kaiserslautern, Germany. The Pennsylvania German Cultural Heritage Center also holds a photocopy of most of the index, which is housed at Kutztown University in Pennsylvania. Contact information for both the Institut für Pfälzische Geschichte und Volkskunde and The Pennsylvania German Cultural Heritage Center can be found in the appendices.

An even larger card file called Die Ahnenstammkartei des Deutschen Volkes (The Master File of the German People) contains about 2.7 million names in more than eleven thousand pedigree files. The original card file is held by the Deutsche Zentralstelle für Geneologie (German Center for Genealogy) in Leipzig, Germany; a microfilm copy of the card file and its indexes is at the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints’ Family History Library (FHL) in Salt Lake City. Contact information for both of these repositories is in the appendices.

Many smaller card files can be found in many local and regional American libraries whose holdings have a German emphasis. You’ll want to concentrate on libraries located where your ancestors or their descendants lived.

Obituaries and Tombstones

In chapter two we discussed death certificates and church burial records, but there are other death records that might yield a village of origin, too. Don’t stop your search for additional death records once you determine a date of death. Each recording of a death is likely to have different information and you don’t want the one you fail to pursue to be the one that would have given you an immigrant’s birthplace.

Newspaper obituaries, especially those published in the first half of the twentieth century, often give place of birth. There are a number of great websites to search for obituaries, including GenealogyBank <www.genealogybank.com>, Legacy.com <legacy.com>, Obituary Central <www.obitcentral.com>, Obituary Daily Times <obits.rootsweb.ancestry.com>, USGenWeb Archives Obituaries Project <usgwarchives.net/obits>, and USGenWeb Archives <searches.rootsweb.ancestry.com/htdig/search.html>.

Sometimes your ancestor’s village of origin will be listed right on his or her tombstone. You can find cemetery information, and even images of many tombstones on these websites: Find a Grave <findagrave.com>, Interment <interment.net>, Nationwide Gravesite Locator <gravelocator.cem.va.gov>, Mortality Schedules <mortalityschedules.com>, and Virtual Cemetery <www.genealogy.com/vcem_welcome.html>.

Use any immigration information you find in obituaries or on tombstones as a starting place and continue searching for additional primary sources that prove or disprove the information.

Newspapers in English and German

While obituaries may be a prime reason for you to look at newspapers for village of origin information, they shouldn’t be the only reason. The ways you might find such information in a newspaper are limited only by your imagination; you may find the mention of a village in articles about your ancestors or their businesses, articles about family reunions recounting history back to the boat, and genealogy columns.

The good news is many old newspaper collections have been digitized and put online, making them more accessible and easier to search than ever before. There are several for-pay websites that either include or exclusively provide newspaper content, including Ancestry.com <ancestry.com>. GenealogyBank <www.genealogybank.com> has a large and growing newspaper collection and includes a number of German-language titles in its stable. A master listing of newspapers in all languages appears on the Chronicling America website <chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/newspapers> sponsored as a joint project of the Library of Congress and the National Endowment for the Humanities. (Chronicling America’s site also includes free access to a smattering of digitized newspapers from across the nation.)

Line up your time and place cross hairs and search for newspapers from the time period of current residence for your ancestor, but also be sure to search for papers published in previous residences because newspapers often shared articles with other publications in communities where people still might have been known.

WHAT IF YOU STILL CAN’T FIND THE VILLAGE?

Despite all these research possibilities, not every ancestor left an adequate trail of bread crumbs that can be followed to a village of origin. In some cases you’ll have information on a German state name but no village within that area. Depending on the size of that state and the time you can put into the project, you might be able to sift through all of the church records for the particular state.

But before you do that, or if you feel you’ve exhausted all the potential records, try another technique, what the renowned genealogist Elizabeth Shown Mills called the “FAN Club” principle in which you research the “friends, associates, and neighbors” of your immigrant ancestor.

This approach extends your search and enlarges the type of “haystack” we talked about at the beginning of the chapter, but sometimes it’s the only way you’ll find information about your own ancestor. Among the “FANs” to pay special attention to are shipmates on passenger lists, next-door neighbors shown in censuses, and executors of wills. Apply the same research principles you used for your ancestor to these “FANs.” If you find the immigrant origin of such a person, it may be worth your while to try and find your own immigrant in that German village’s records.

AFTER YOU HAVE FOUND THE VILLAGE

After you’ve found the village name of your immigrant in one or more sources, you can move on to further steps:

- finding that village in Germany

- acquiring more knowledge about Germany and its language (chapters four through six) and

- working with records from the area of that village (chapters seven through twelve)

Ravenstein’s Atlas, the Meyers Gazetteer, and German road atlases (all discussed in detail in chapter five) are excellent resources for identifying villages, but you can start by trying a Google Maps <maps.google.com> search for the village name.

However, simply finding the village in Germany can be an adventure because on average a German place name is used for three separate villages in different parts of Germany. (It’s no different than the way town names such as Springfield or Columbus are used in multiple states in the United States.) And because there are some unique village names, the flipside is that a fair number of names are used more than a dozen times! That makes the odds very good that you could be researching in the wrong village, even if the name matches your records.

Just as there are ways to distinguish your ancestor from another person with the same name, there are ways to distinguish villages of the same name. You’ll need to do this before you start researching any particular village. Sometimes the record you find will give further clarification by linking the village name to that of a larger town or another “geographic suffix.” For example, western Germany has the large city Frankfurt am Main while Frankfurt an der Oder is a city on present-day Germany’s eastern border with Poland. The “geographic suffixes” are used to distinguish the two Frankfurts and in this case show the names of the rivers than run through the respective cities.

You might also be able to differentiate based on the immigrant’s religion. If the immigrant was Roman Catholic and all but one of the identically named towns are in Protestant areas, concentrate on the one in the Catholic area.

You also need to be skeptical if the place of origin is listed as a large city; while the possibility of being from an urban area increases among the “second boat” immigrants, your ancestor might have named the large city because it is near where he is from and more likely to be recognized than the smaller, rural village where he actually lived. A possible workaround for this situation is to look in FamilySearch’s International Genealogical Index for clusters of the surname in villages surrounding the larger city.

Of course, you may also come to realize that there is no German town by the name you have found. There are several possible reasons for this. A phonetic garbling of the name over generations could have taken place (we’ll consider German phonetics in some detail in chapter six). Also, the town may have been absorbed by a larger entity and the smaller village’s name became lost in the merger. Finally, a fair number of former German towns are now in other countries that have renamed the villages in the new language.

As an example of several of these concepts: An immigrant’s granddaughter wrote that her ancestor came from “Neuhof by Vitzgow.” An atlas from the 1880s showed a town “Nendorf” near the larger city of “Wutzkow.” This area of Pommern is now in Poland, and Wutzkow is now known as “Oskowo.”

As you research German place names, you may discover a village name that is identical to or a form of the surname you are searching. Many people will assume that their ancestor must be from this village. They’re usually right in theory but wrong from a sense of practical application and here’s why: Most Germans adopted surnames in the 1300s and a placename surname adopted at this time would have indicated the person was originally from the town in question but no longer living there. An example: Johannes is born in the Rheinland town of Partenheim before Germans took surnames. He later moves to nearby Sprendlingen and at some later point commoners begin taking surnames to differentiate themselves from one another. Because he’s already been called “Johannes from Partenheim,” he becomes Johannes Partenheimer. If his descendants attempt to find their eighteenth- or nineteenth-century immigrant in Partenheim, they’ll be technically correct but unlikely to find any evidence because most German records of commoners date only from the 1500s or later.