This map outlines the prime areas of emigration in “first boat” German emigrants; clockwise from farthest left: Alsace, Saarland, Pfalz, Württemberg, and Baden.

Although it’s tempting to jump right in and start your genealogy research with an immigrant ancestor, it’s vital to follow the genealogy principle we discussed in chapter one: Always start your family history research with yourself and work backward one generation at a time. How quickly you’ll reach the point of dealing with an immigrant ancestor depends on a variety of factors. You may already have a well-documented history of your family that shows who the immigrant ancestor is in one of your family lines and, perhaps, even accurately recounts where that family originated in Germany. If this rare-and-seldom-seen scenario happens to you, count your lucky stars.

If you have been handed down immigration information, you’ll need to verify it with your own research, and when you do, you’ll likely find that it has been garbled in some way; for example, the alleged “immigrant” turns out to have been born in America and his namesake grandfather is the real immigrant, or the village name has been phonetically transmuted over the generations into a place name that can’t be found in Europe.

It’s far more likely that you’ll need to methodically research back several generations to get to an immigrant. Don’t rush through later generations in search of the boat. Take your time and verify everything, establishing clear, credible connections between each generation, so you know you are following the right line. As you establish the names of the earlier generations, you’ll be able to research those ancestors using the primary and secondary sources mentioned in chapter one. These sources will reveal the immigrant ancestor. You won’t know from an individual’s name whether she was an immigrant; you’ll have to find documentation in records.

This chapter describes the immigration of German-speaking peoples in more detail and explains the types of U.S. records that are your best bets to yield immigration statements or clues.

Even if you already know who the immigrant is in your family, you’ll still want to research that ancestor thoroughly to make sure you don’t overlook any important information that will help you later. It’s a good habit to put together a chronology about your immigrant ancestor (actually, for each one of your ancestors). A chronology lets you look at the events of the ancestor’s life in time sequence, which will show you any gaps that exist in your ancestor’s biography and (using those “time and place” cross hairs mentioned in chapter one) help you identify the additional types of records to check for more information.

In the case of an immigrant ancestor, it’s crucial to find documentation that proves the actual date of arrival in America. Descendants often find this date to be symbolic of their family’s transition. The date is also of great genealogical importance because it is the “teeter-totter” point between the Old and New Worlds and, logically, before this point you’ll find records only in Germany; after it, the documents will all be in the United States. (As with every great concept, there are some exceptions: A small minority of German immigrants made multiple trips across the Atlantic; some German records, such as personal letters and newspaper advertisements for heirs, may be found after the immigration date; and some U.S. records may mention pre-immigration events. Be aware of these exceptions, but also realize you’re less likely to encounter them.)

Another important step in immigrant research is determining the original name of the immigrant ancestor because the transition time between the Old and New Worlds is when the most changes—be they variant spellings, translations, or just plain phonetic garbles—are bound to happen. You may encounter a number of spellings. In order to correctly identify the immigrant, gather records made by or for the ancestor for the span of his life (from birth to marriage to death). You’ll also need to apply some facts about the German language and German names that are detailed in chapter six.

When you establish the chronology of the immigrant’s life, be sure the time line makes sense and doesn’t have irreconcilable inconsistencies. When we get to the chapters on German documents such as church records, you’ll be advised to carry the research forward in time beyond the date of immigration to eliminate the possibility that your suspected immigrant is not just someone with an identical name. For instance, if your suspected ancestor keeps having children baptized in Germany after the immigration date and the person is buried in Germany, it becomes obvious that he is not really the immigrant.

Wherever possible, you’ll want find multiple recordings of an immigrant’s signature to bolster your case for identification. To do this, you’ll often need to track down original documents (as opposed to abstracts or transcripts or ones recopied in courthouse files). Although this takes extra work, it can have a big payoff. Matching a ship register signed by the immigrant to the signature on his original last will and testament made more than forty years later can give you the proof that you have the right person, especially when the immigrant has a common name. The signature match may not always be perfect; an immigrant’s hand could be old and shaky in later life, or he might have learned to write English cursive instead of his original German script. But there usually will be some common characteristics to the signatures found on documents such as deeds or estate petitions and papers.

Finding these documents can be difficult. Sometimes you’ll need to search for your ancestor as a witness to a will or other documents, in which case his name is not likely to be indexed. To see if your ancestor was a witness to a document, use your “time and place” cross hairs and research deeds, estate petitions, and other court records created during your ancestor’s life (from age of majority) in your ancestor’s home county and surrounding area. Your ancestor would have served as a witness for people he knew, so look for his signature on documents created for his parents, siblings, children, uncles, cousins, in-laws, and neighbors (who were often some sort of relation either by blood or marriage). If you have names for these people, you can be more precise with your searches.

Chapter one has a brief history of German-speaking people in the United States, but as you begin to trace ancestors back to the point of immigration, you’ll need some additional background about their settlement in America. In the broadest terms, we noted that historians divide German immigrants into two great waves or “boats.” Here are some of the many things that distinguish these waves, some of which may help you determine whether your particular ancestor “fits the profile” of an immigrant from the wave applicable to the time period you are researching.

The first wave includes the small number of immigrants in the seventeenth century and then all of those coming in the eighteenth century. A majority of these immigrants came either as a family unit or as part of “cluster” or “chain” immigration to America. In “cluster” immigration, several families from the same or adjacent towns in Germany left together and then usually ended up traveling on the same ship together, too. “Chain” immigrants were those who were motivated in some way by previous emigrants to take the plunge for the New World themselves. Sometimes, the first link in the chain simply sent home letters that described life in America, especially its advantages. In other cases, the lead immigrant actually funded the transportation of the next “link,” with repayment occurring either when that second link reached the destination or sometime afterward.

A majority of the “first boat” immigrants were originally from states clustered in the southwestern corner of Germany. These included the Pfalz, Saarland, Baden, and Württemberg as well as mostly German-speaking Alsace (now part of France). These emigrants, by and large, used the Rhine River as an eighteenth-century “superhighway,” often engaging an agent called a Neulander to help grease the way (with the equivalents of group discounts or bribes as necessary) past the many river tollbooths manned by individual states along the Rhine. When the emigrants reached the border of the Netherlands, they needed to show that they could afford the passage to America or agree to be indentured to pay the fare because the Dutch tried to avoid becoming a dumping ground for the poor.

Despite this restriction, some emigrants did work for some years in the Rotterdam area and can be found in church records there. There are also a few notarial records, which are copies of contracts entered into between ship owners and groups of emigrants, that serve as the only embarkation records from this era. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, ships bound for Colonial America were required to stop for at least a short time at a British port before making the transatlantic crossing. Through the 1730s, the crossing took eight to twelve weeks, but by the later colonial period the crossing time had been shortened to six to eight weeks.

Philadelphia was the port of entry for about 80 percent of the “first boat” German immigrants. Baltimore and New York were the secondary ports with just a few German-speaking immigrants coming into harbors in Boston and Charleston, South Carolina. Upon arrival, immigrants had a week to settle their accounts with the ship captain, and anyone who couldn’t pay after that time was sold as indentured labor.

This map outlines the prime areas of emigration in “first boat” German emigrants; clockwise from farthest left: Alsace, Saarland, Pfalz, Württemberg, and Baden.

After arriving in America, the Germans were not apt to wander. They left the Scots-Irish to be the first settlers of areas. Most German immigrants either bought farms in the countryside or took up trades in market towns established by the British to serve the surrounding farmers. Overwhelmingly, the “first boaters” were motivated to come to America in search of the economic opportunity made possible by reasonably priced land. With the German states stuck in a feudal economy until the early 1800s, the best description of the typical eighteenth-century immigrant is that of “the more prosperous peasant farmers.” (Occasionally people will say that their German-speaking eighteenth-century family was nobility because the prefix “von” is attached to the name. Virtually no German nobles immigrated because they thrived in feudal society and would have had no interest in trading in a well-appointed castle for a log cabin in America’s wilderness!)

The stereotype of Germans coming to America for religious freedom was true only for the sectarian religious groups who were persecuted in Europe. These groups made up less than 10 percent of the “first boat” immigrants. About half of this wave were Lutherans, the most populous Protestant denomination in the German states, and a third were from the second-largest mainstream Protestant group, the Reformed.

After the first couple of generations, these Germans were among those who joined the westward expansion of the United States, first moving on to the Midwest and then eventually to the Pacific Coast and Rocky Mountain states. Those who left the East Coast area often intermingled with the emerging tsunami of the second-wave immigrants.

The second wave of immigrants spans from 1800 to 1920, when an estimated five million German-speaking immigrants came the United States. In this second wave, nearly everything about German-speaking immigration to America changed. While there was still some cluster and chain immigration taking place, many more single families (or just plain single people) boarded ships and came across the ocean.

While “first boaters” were from the southwestern German states, the “second boater” emigrated from more eastern regions (Bavaria) and northern regions (Sachsen, Pommern and Brandenburg). The religious demographics of the “second boaters” also changed, with Protestants and Roman Catholics making up about equal numbers in this massive group.

Rhine-to-Rotterdam was no longer the emigrant superhighway. Immigrants used other rivers and, as the nineteenth century wore on, railroads to get to the ports of Bremerhaven (the harbor for the ancient city-state of Bremen) and Hamburg. Hamburg, as you’ll see later in the book, has excellent embarkation records, while most of Bremen’s records have been destroyed as a result of various disasters—some accidental, some intentional.

New York City was by far the most common port of entry for the “second boaters.” Philadelphia was reduced to a secondary role along with Baltimore and the emerging port of New Orleans, which offered easy access to prime second-wave destinations such as Texas and the upper Midwest from Wisconsin and Illinois to the Dakotas. Many immigrants who entered through East Coast ports found that they didn’t have as much in common with the descendants of the southwest Germany-based “first wavers” and as a result moved past the East Coast to the Midwest if they could.

While many immigrants in the second wave became the industrious farmers of America’s breadbasket, there was also a significant entrepreneurial spirit to the “second boat.” The “first boat” of pioneers had dotted the United States with concentrations of Germans and savvy businessmen who found ready markets for their goods in these German-dominated areas, spurring even some in Germany’s upper classes to come to America. With the advent of a capitalist economy in the German states, there also was a significant “lower class” in Germany that found better opportunities for industrial labor in America. And, after the failed Revolutions of 1848, a significant number of university-educated Germans emigrated when they realized that the governments of the German states were moving toward an empire led by autocratic Preussen rather than a republic like the United States.

This map outlines the prime areas of emigration in “second boat” German emigrants; from south to north: Bavaria, Sachsen, Brandenburg, Pommern.

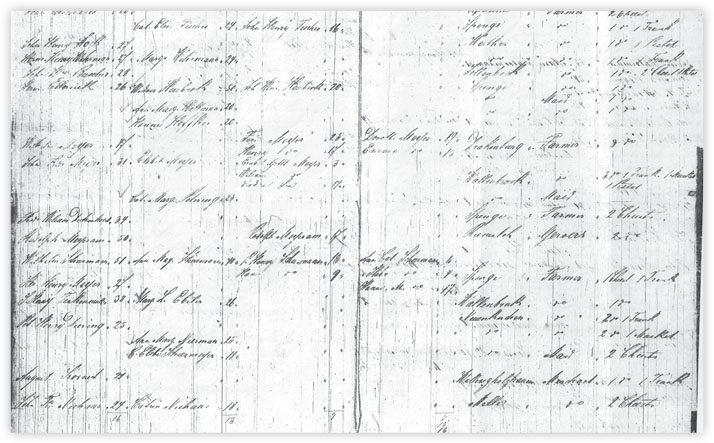

Passenger list showing a lot of Germans

Information about an ancestor’s immigration can potentially be found on many types of records. Some of these records were created as a direct result of the ancestor’s transatlantic passage, while other records are more indirect. We’ll tackle the more direct records, such as passenger lists, embarkation records, and naturalizations, first.

We established that the date of arrival in America is the important “teeter-totter” point in the life of your immigrant ancestor. Passenger arrival lists are the records found at the fulcrum of that teeter-totter and, fortunately, there are more of these records for German-speaking immigrants than any other ethnic group.

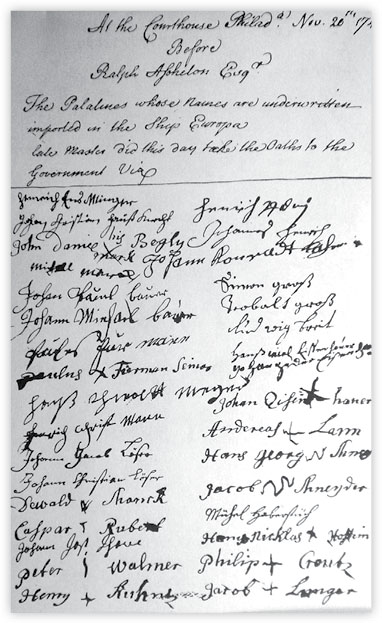

German immigrants were better documented because they were the largest “foreign” group (that is, not already subjects of the British crown) in Colonial America. The British government didn’t require any sort of passenger lists for ships arriving in colonial ports. However, Pennsylvania’s legislature became fearful of the German influx, and in 1727, mandated that ships keep lists of the “foreign” immigrants they brought to the port of Philadelphia. Nearly all these “foreigners” were German-speaking immigrants. This mandate produced the only large body of passenger lists from the Colonial period. The lists that have survived have been published as Pennsylvania German Pioneers, which can be searched on subscription site Ancestry.com <ancestry.com>.

According to the law, three lists were kept: A captain’s list of all those aboard; an Oath of Allegiance to the British king (signed only by males age sixteen and over); and an Oath of Abjuration that released the signer from being subject to his former sovereign in the German states (also signed only by males age sixteen and over).

A 1741 Oath of Allegiance list from Philadelphia

Unfortunately, most of the captain’s lists have not been preserved, but the Oaths lists give that much-sought “fulcrum” for thousands of “first wave” German-speaking immigrants. In addition, the Oaths lists contain the actual signatures or marks of the immigrants taking the oath, which can help you separate your immigrant ancestor from a person with an identical or similar name.

The lists published in Pennsylvania German Pioneers run through 1808 and therefore cover the early Federal period when Philadelphia remained the new nation’s primary port. Overall, though, this era saw less immigration because of the Napoleonic Wars. However, when the wars ended in 1815 and Europe returned to peace, immigration began to surge, and that led the U.S. government to require every major port of entry keep passenger arrival lists.

These lists have been preserved by the National Archives (with microfilms of the original records and indexes for various ports and time periods). Many of the these lists have been digitized and put online by Ancestry.com and other websites. Most attention has been given to the New York lists. Start with these, but if you don’t find your immigrant, don’t give up your search. Try New Orleans, Baltimore, and Philadelphia records even if they aren’t digitized. Access the microfilm of these records through the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints’ Family History Library (FHL) <www.familysearch.org>.

In theory, the lists should offer you an impressive amount of data: the person’s name, nationality, place of birth (often just listed as a country or German state name), ship name, date of entry to the United States, age, height, eye and hair color, profession, place of last residence, name and address of relatives he is joining in the United States, and amount of money he is carrying. While there are columns for all of this data, many of the lists are only partially completed with many columns left empty. But there is always the hope that your immigrant’s list will be one of the complete ones, and any amount of information is better than none.

Until 1828, immigrants were supposed to register with a court in their port of arrival, so if your immigrant ancestor arrived during that time, check the local court records after you determine his port of entry.

Immigrants were not required to become citizens but most did because citizenship rights (including the right to vote and sometimes ownership of property) hinged upon completing the naturalization process. And quite a “process” it was, especially before the twentieth century when it was ordinarily performed on the state or local level. Profiling the many changes made to naturalization laws over the years could fill an entire book. This section covers some of the basic concepts of the naturalization process to help you pursue these very helpful records.

While the American colonies were under the control of Britain, British Isles immigrants to the colonies didn’t need to be naturalized because they were citizens on both sides of the Atlantic. As a result, nearly everyone naturalized during the Colonial period was a German-speaking immigrant.

Most naturalization records from the colonial era are from Pennsylvania, though a few Maryland and New York state naturalizations have survived with just a smattering from other colonies. Before 1740, persons seeking naturalization had to petition their colony’s legislature for a new law to be accorded citizenship. This was a difficult process, so in 1740 the British Parliament enacted a streamlined procedure that allowed colonial supreme courts to perform naturalizations.

Throughout the colonial era, immigrants had to be in America at least seven years before they could apply for naturalization. So if you find a naturalization record from this era, you can use the date of the naturalization to determine the absolutely latest date the immigrant could have arrived in America (seven years prior), which will help you identify when and where to look for records. Information found on typical colonial-era naturalization records includes the name of the individual, his city or township of residence, and the date when he had last taken the sacrament. (Taking the sacrament was one of the qualifications for colonial naturalization, although some religious groups, such as Jews, were exempted.)

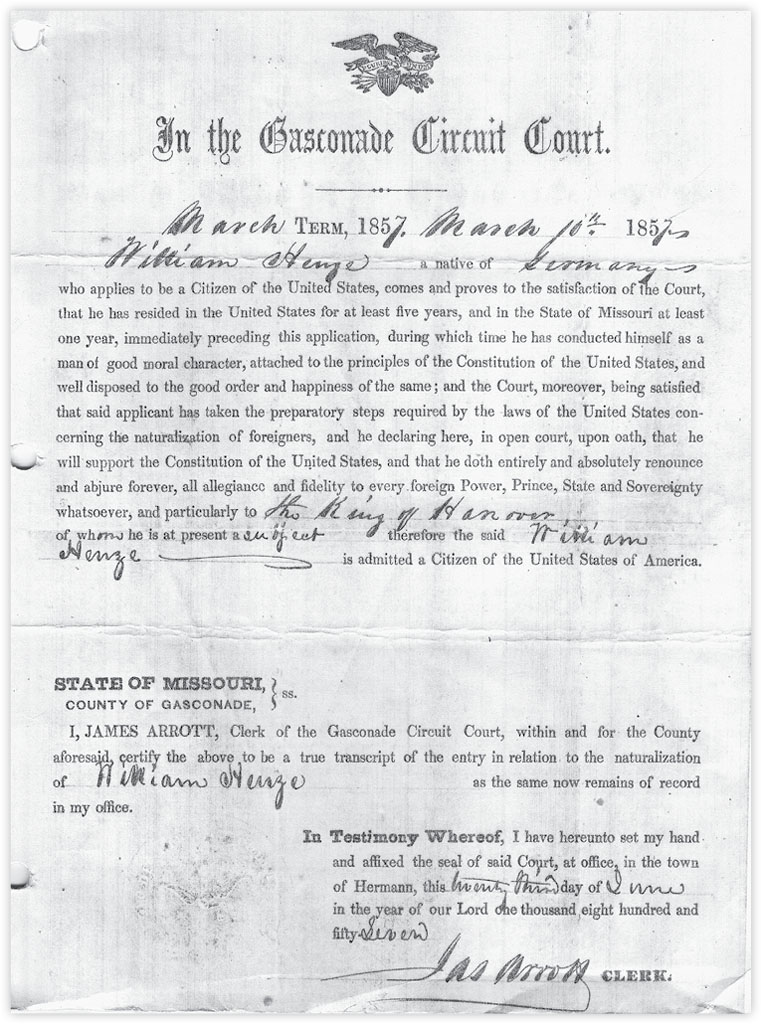

After the American Revolution, the new federal government established laws to control naturalization, but the process was largely executed in state and local courts until early in the twentieth century. The new federal laws created a two-step naturalization process. An immigrant filed a “Declaration of Intention” (nicknamed “first papers”) and after he fulfilled a minimum time period (which varied but for most of U.S. history was five years’ residence in the country) he could make a “Naturalization Petition” (the so-called “final papers”) for a court to consider granting citizenship. Often, the Declaration of Intention will list the exact ship and date on which the immigrant arrived, and this information opens the door to passenger list research.

This is an example of nineteenth-century first papers. It is the naturalization certificate for William Henze from 1857. Image courtesy of Dr. Dwayne V. Smith.

Naturalizations can be found at almost every level—state courts, county courts, federal courts, even places called mayor’s courts. Finding both sets of papers can be complicated because the immigrant could file his Declaration of Intention in one court and then years later file his Naturalization Petition in another court in a different location. The Naturalization Petition doesn’t always give full references to the location of the Declaration of Intention. Keep an open mind when searching for both sets of papers. Use your chronology of the immigrant’s life to identify all the different locations where papers could have been filed.

It’s important to note that in the nineteenth century, wives and children received citizenship derived from their husband or father so you typically will not find separate naturalization records for them.

There was also a special allowance made for immigrants who served in the Union Army during the American Civil War. These soldiers could receive citizenship by presenting a copy of their honorable discharge from the Union Army and proving at least a year of residence in America. Thousands of immigrants from all parts of Europe were naturalized under this process. One volume that lists these military petitions for naturalizations is Military Petitions for Naturalization Filed in the Philadelphia (County) District Court 1862–1874 by Jefferson M. Moak.

The naturalization process became more standardized when the U.S. Bureau of Immigration and Naturalization (predecessor of today’s U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Service) was formed in 1906. After this date, most naturalizations were performed in federal courts and the records are in the custody of the National Archives.

It stands to reason that if records were kept on the arrival side of the ocean that there might also be some documents kept in Europe as German-speaking emigrants left. There weren’t many records created for “first boaters.” But, in the main port of Rotterdam, you may find a few notarial records as well as evidence in church books.

Embarkation records for the “second boat” can be more difficult to find. Bremen’s port, Bremerhaven, was the number-one port of exit in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, but relatively few records exist for it. The lists created between 1906 and 1931 were destroyed by Allied bombs in World War II. The earlier records fell victim to something much more preventable: lack of storage space. Bremen began keeping records in 1832, but when these records were deemed a waste of room, all the lists from their beginning in 1832 through 1872 were destroyed, and thereafter only the lists for the current and two previous years were kept until this policy was repealed in 1907, though in some places the practice did not stop until 1909. Duplicates of some twentieth-century lists and a handful of earlier lists exist in Bremen’s archives.

While Bremerhaven’s records are lost, Hamburg’s records still exist. Hamburg kept nicely detailed lists of departing emigrants from 1850 to 1934, and these lists have been indexed and preserved. You can search the index in the German records section of <ancestry.com> and find microfilm copies in the FHL in Salt Lake City.

Finally, there are also a smattering of embarkation records relating to Germans leaving through other exit ports such as Antwerp, Belgium, and Le Havre, France, and the FHL has scattered holdings relating to them. Search the library’s holdings at <familysearch.org>.

In addition to the direct records we’ve just profiled, there are a slew of possible sources that may suggest your ancestor was an immigrant. Actually, it’s important to evaluate all records and documents about your ancestor for immigration clues, but some records will be more helpful (and more likely accurate) than others. The following records are the ones that you may run into most frequently. In chapter three, you’ll find a larger list of record groups that will help you pinpoint the immigrant’s exact village origin.

U.S. census records help genealogists find more answers, including about immigration, than any other type of record. The federal census is mandated by the U.S. Constitution and has been taken every ten years since it was begun in 1790. Current law requires that the census population schedules stay private for seventy-two years after the census was taken, so the 1940 headcount is the latest one now available for research.

The first six censuses (1790 to 1840) named only the head of each household and grouped other members into age categories. From 1850 to the present, every person’s name, age, and varying other data have been recorded.

For those seeking information on immigrants, the mother lode comes from 1900 onward, but even a couple of the “head of household” censuses asked for the number of foreigners who had not been naturalized. Later nineteenth-century censuses began asking for each individual’s birthplace (though ordinarily only the country of origin will be named), later added the birthplaces of each individual’s father and mother, and some of those in the twentieth century added questions on the number of years an immigrant had resided in the United States as well as naturalization status and year. The "Immigration Information Available in U.S. Censuses" sidebar shows the exact phrasings of the questions related to immigration and the census years to which they apply.

You can search census records on the subscription websites Ancestry.com <ancestry.com>, Archives <archives.com>, and Fold3 <fold3.com>, and for free on FamilySearch <familysearch.com>, HeritageQuest Online <heritagequestonline.com>, and the USGenWeb Archives Census Project <usgwarchives.net/census>.

The census is a good starting point, but don’t take it as absolute proof. Someone else may have answered for your ancestor and gave inaccurate information. Dates of naturalization and immigration may not match up between censuses. The simple explanation is your ancestor’s memory may have slipped or someone else provided incorrect information on his behalf. Use the census information to help focus your search for immigration records.

In the United States, state and local governments are responsible for issuing vital records including birth, marriage, and death records. While the records in many New England states date to Colonial times, most states didn’t begin requiring and issuing vital records until after 1850 and some waited until early in the 1900s. Birth records offer little proof of immigration, but marriage licenses and death registers or certificates often can be helpful.

Historically, most couples had to state their places of birth on their marriage license application forms, and these forms often also asked for names of their parents as well as the parents’ places of birth. Death registries and certificates usually ask for birthplaces of the deceased and his or her parents, but it’s not unusual to find that the person giving the information for the certificate—perhaps an in-law or uninterested non-relative—gave “don’t know” as the answer to many of these questions.

You can search vital records on the subscription website Ancestry.com <ancestry.com> and for free on FamilySearch <familysearch.org>. You often can also find information about a state’s vital records collection through the state’s historical society. The Family Tree Sourcebook by the Editors of Family Tree Magazine is an excellent fifty-state directory that includes a county-by-county listing of when vital records were started in each state and where they are kept. It also includes listings of state archives, libraries, societies, and publications related to genealogy records. VitalRec.com <www.vitalrec.com> also has a complete list of records available for each state.

Church records serve as important vital records substitutes, and they are especially helpful for ancestors born before vital registration was required. Most of the churches attended by German-speaking people kept detailed registers of baptisms, marriages, and burials. As with civil birth records, baptisms have little bearing on immigration. Marriages occasionally give birth or previous residence information. (Some, but not many, pastors also continued the German tradition of naming fathers of the groom and bride in the marriage record of their children.) Burial records can range from very simple entries that merely list a name and date and place of burial to complete obituaries written directly in the burial register. Once again, these burial records parallel their civil counterparts in that the information given may depend upon both the helpfulness of the family or non-family member reporting the information and the knowledge of the pastor writing the register. Chapter eight details how to find these church records.

It’s important to note that church records, particularly from the eighteenth century and from rural areas, may be spread across multiple congregations, as rural and eighteenth-century congregations almost always shared ministers with other congregations. Even if one particular congregation seems to have “all” of a particular generation’s records, you’ll do well to learn the congregation’s history to discover the churches that shared their minister and then investigate the records of those congregations, too. There is also the possibility that individual pastors kept their own private records.

As with other ethnic groups in America, Germans enjoyed the company of other German-speaking people and many German social organizations were formed throughout the United States. Many of these groups have left behind history books, membership rolls, newspapers, or other types of communications with members such as newsletters, flyers, and the like. Some records will mention new immigrants when they joined the group or celebrated occasions.