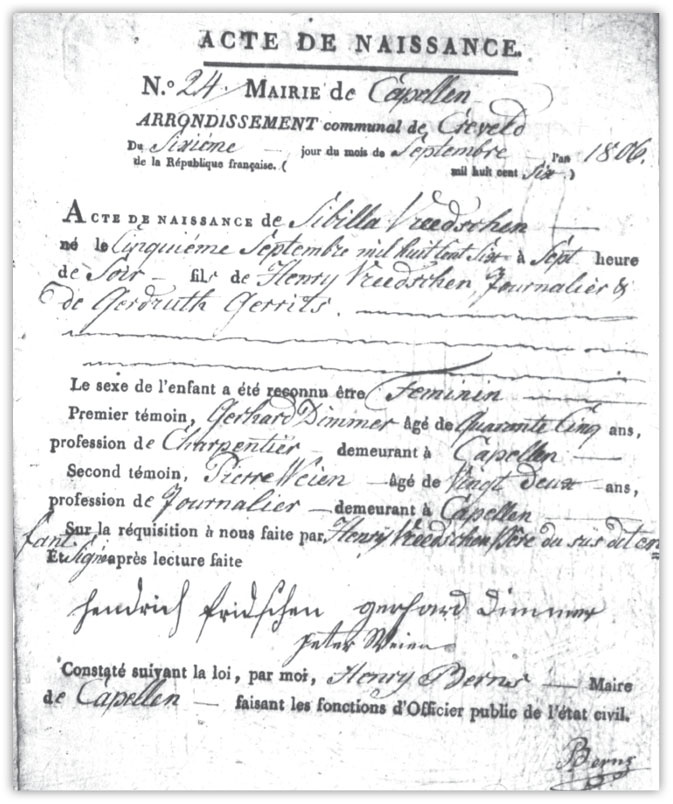

German birth record from the French Era (recorded in 1806); Fretschen, Sibilla birth FHL Intl film 1047403 Germany, Preussen, Rheinland, Capellen (Kr. Mörs) Civil Registration year 1806 Nr. 24

While many researchers with German ancestry set a goal of tracing their forebears as far back in time as the earliest church books, the civil registrations of births, marriages, and deaths that by and large began in the nineteenth century in the German states are important to any family historian. For those with emigrants during the 1800s or 1900s, these registers provide the generational links needed to work back into the era in which there are only church records. And for those whose immigrant ancestors came to America in the 1700s, the civil registers are a way to help bridge a connection with distant modern cousins.

As a general matter, if the area you are researching kept civil registers during the time period you are researching, these registers will be more helpful than parish registers because the latter may give only a baptismal and burial. The civil registers will always give you birth and death dates.

An empire-wide law mandating civil registrations didn’t go into effect until 1876, but some states began keeping records before this time. Your chances of finding civil registrations that date to before 1876 increase the farther west your German-speaking ancestors are found. Chapter four details the profound effect the French Revolution had on the German states of the time. One of these effects was the introduction of civil registration. France’s revolutionary government introduced registration within its own territory in 1792, and as the French marched farther east into Germany, first under the banner of the revolution and then to solidify the dominance of French Emperor Napoleon I, the registration requirements were extended across most of the western third of Germany, at least temporarily. Alsace and Lorraine began civil registration in 1792. Pfalz, Rheinland, Baden, and parts of Hessen all were conquered by France in the 1790s and began civil registration during that time (Rheinland and Pfalz’s registrations begin in 1798 and continued; Baden instituted Kirchenbuchduplikat beginning in 1810). Westfalen and Hannover began civil registration in 1808 and 1809, respectively, while Oldenburg’s registrations were kept only from 1811 to 1814 while under French influence.

A few small additional areas added civil registrations in the mid-1800s and some of the western German areas mandated duplicate church books (Kirchenbuchduplikat, described in chapter eight) as a way of continuing the flow of information on vital statistics. In 1874, Preussen began civil registration in its provinces, and in 1876, an empire-wide law mandating registrations went into effect, starting records in the final holdout states of Mecklenburg, Sachsen, Thüringen, Bavaria, and Württemberg.

Most of the civil registration records from 1792 through 1805 were kept in the French language and used the calendar instituted by the French Republic, which secularized the calendar while celebrating the founding of the republic in 1792. Napoleon I abolished the French Republican Calendar at the end of 1805.

According to the French Republican Calendar, the new year began on the autumnal equinox on September 22. The French Republican Calendar year had twelve months of thirty days each. Every year five “complementary days” were added to the end of the year to bring the total number of days to 365. In lieu of the Gregorian Calendar’s leap days, every four years (beginning with the third year of the Republic) an extra complementary day was added. (Days were added to years 3, 7, 11, and so forth.) During the period that the French Republican Calendar was in force, the standard Gregorian Calendar had only two leap years (in 1796 and 1804, since the prime reform of the Gregorian Calendar had been to eliminate leap days in century years unless they were divisible by 400).

The months were given new names and the years of the Republic were often designated by Roman numerals. For example: The “thirteenth day of the month of Pluviôse in the seventh year of the Republic” would have generally been written as “13 Pluviose VII.” The complementary days (which were named for feasts) were recorded in two ways. They might be called by the name of the feast, for example: “the feast day of Labor in the ninth year of the French Republic.” The second was merely using the number of the day and year: “the third complementary day of the ninth year of the French Republic.” The FamilySearch Research Wiki, available at <familysearch.org/ask/researchWiki> article on the French Republican Calendar has a conversion table that converts French Republican dates to their Gregorian counterparts.

German birth record from the French Era (recorded in 1806); Fretschen, Sibilla birth FHL Intl film 1047403 Germany, Preussen, Rheinland, Capellen (Kr. Mörs) Civil Registration year 1806 Nr. 24

The data that you’ll find in German civil registrations vary only slightly over time as different German states had their own preprinted forms that were used. The good news is an estimated 98 percent of the German population complied with the registration laws, so nearly all Germans alive when registration was enacted can be found.

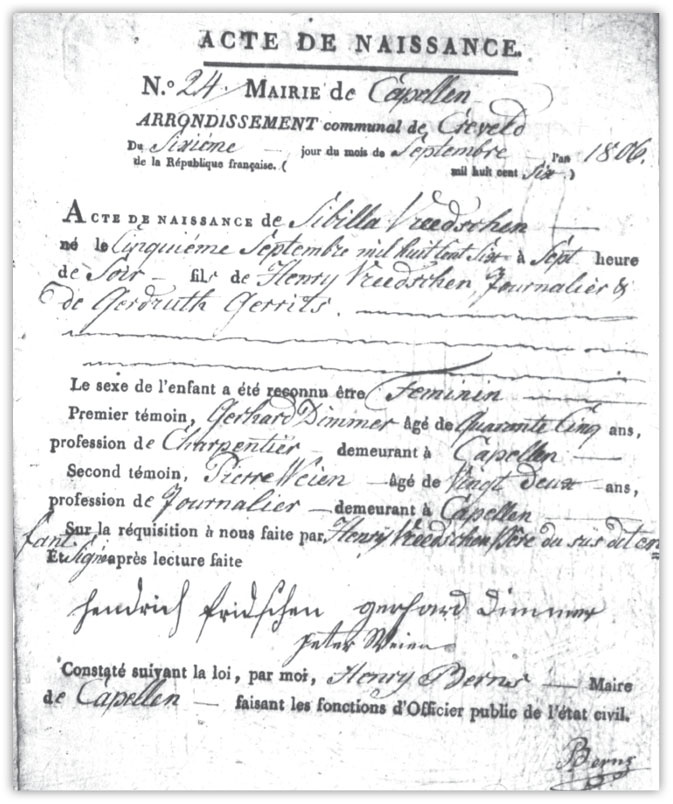

German birth record from 1874;

Mandt, Johann George, birth registration from Schwarzenborn, Hessen-Nassau, Germany

The records in the birth register (Geburtsregister) ordinarily give the child’s name and gender as well as date, time, and place of birth. Information about the father includes his name, age, occupation, and residence. For the mother, you’ll find her name (including maiden surname) and often her age. The records also include names, ages, and residences for witnesses, and the preprinted forms of some states asked for the religion of the parents. In most cases, the actual registration of the birth was made by the father of the child, a neighbor, or the attending midwife. It’s worth locating the original registration whenever possible as corrections and additions are sometimes made as marginal notes to the original registration.

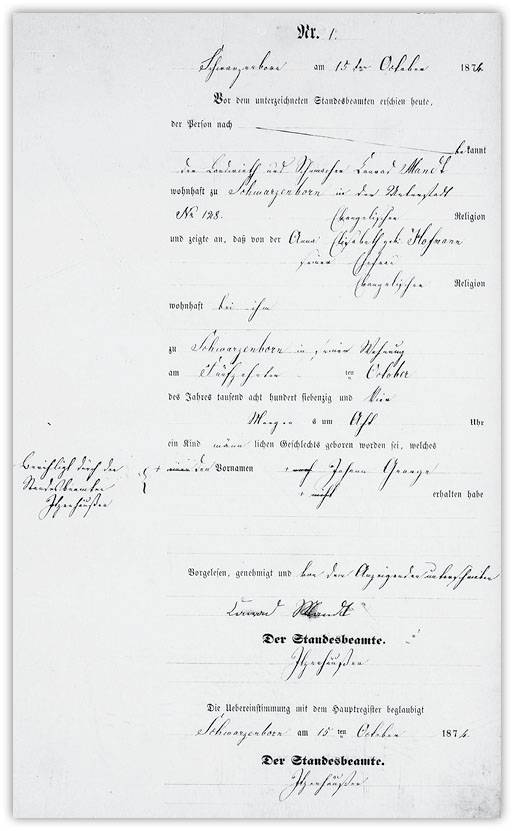

German marriage record from French Era (1810); Müller, Jakob and Helena Schepers marriage FHL Intl film 1045927 Germany, Preussen, Rheinland, Kr. Geldern, Budberg Marriage Acts 1810 #7

Marriage registers (Heratsregister; sometimes called Eheregister or Trauungen) were usually recorded in the village where the bride lived. These records include the following information about both bride and groom:

You’ll also find information about the bride’s and groom’s parents including their names, residences, occupations, marital status, and whether living or dead at the time of the marriage. Notations on whether a parent or guardian gave permission for one of the partners are sometimes included, as are the names, ages, and relationships of witnesses to the wedding.

So-called “marriage supplements” (Heiratsbeilagen) might also be filed with vital records. These supplements in support of the marriage application may include documentation of the groom or bride’s birth, deaths of their parents, or even the groom’s release from military service. The documents can contain information about earlier generations.

When you cannot find a marriage record, realize that there were times when people intended to marry and either could not (due to legal property restrictions, for instance) or did not follow through (for a variety of reasons, “cold feet” among them). There are several types of documents such as prenuptials, marriage permissions, and proclamations that may be found in court records and are these are discussed briefly in chapter nine.

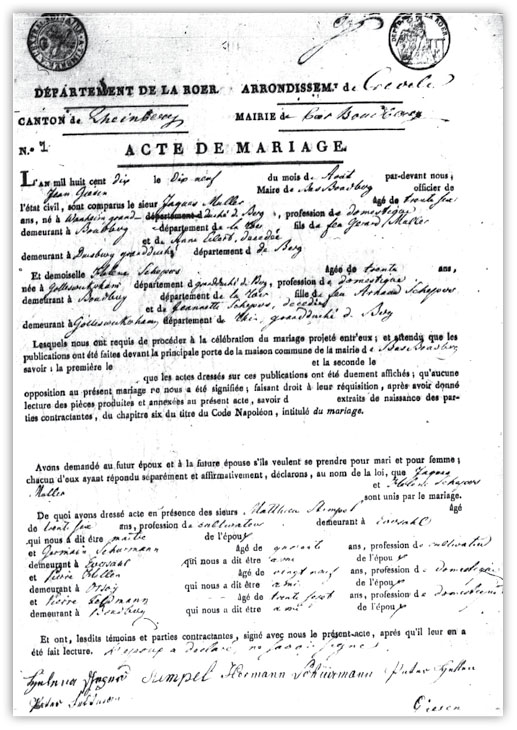

German marriage record from 1874; Loeber, Ludwig and Margaretha Figge, marriage registration from Balhorn, Hessen, Germany, in 1874

The death register (variously called either Sterberegister or Totenregister) contains the following data:

Names and residences of spouse and parents are sometimes included, as is the dead person’s religion. Register entries include the following data on the informant: name, age, occupation, residence, and relationship to the deceased. As with any death record, the accuracy and completeness of the information given is only as good as the knowledge of the person giving it.

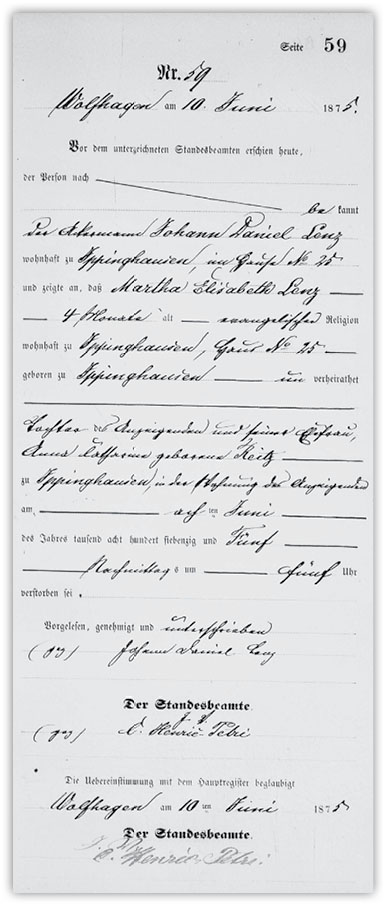

German death record from 1875; Lenz, Johann Daniel, death registration from Wolfhagen, Hessen Nassau, Germany

Getting a look at German civil registration records, as with so many of its documents, depends upon localized circumstances. Some of the earliest records—those dating to the era of French dominance—have been microfilmed by the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints Family History Library (FHL). The FHL has also microfilmed a fair number of the records for Preussen’s many provinces for the first few years of registrations, which began in 1874. The FHL’s FamilySearch website <familysearch.org> also has begun adding collections of digitized civil registrations from Hessen’s state archives in Marburg. These are online with digital images you can browse at <familysearch.org/search/collection/1768560>, although the viewing of many of these collections is still often restricted to Family History Centers (find locations at <familysearch.org/locations/centerlocator>) or awaiting release from privacy blackout periods.

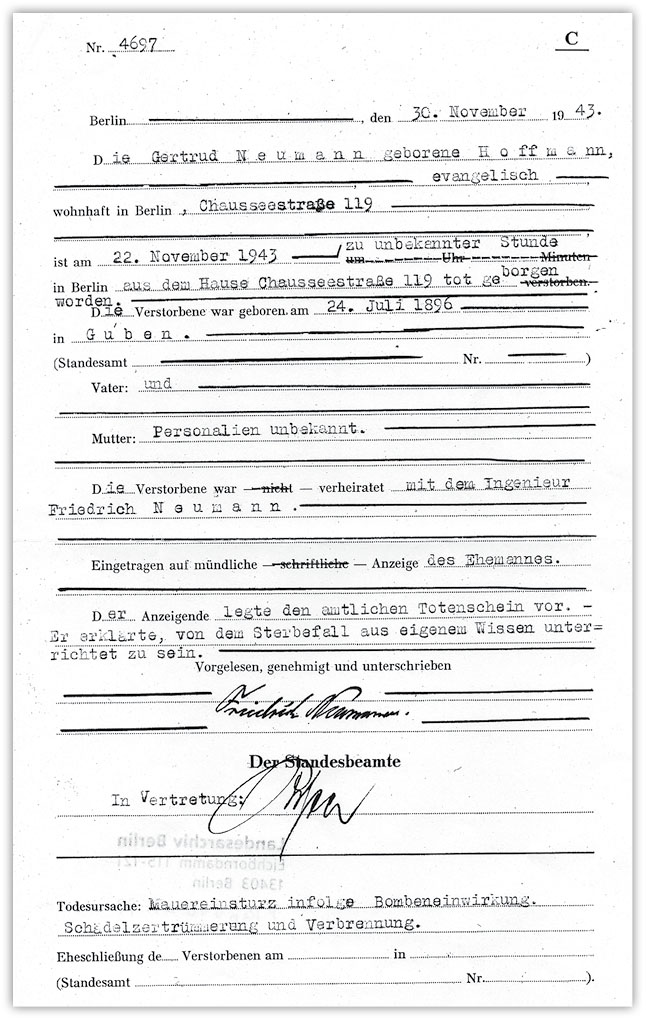

German death record from 1943; Neumann, Gertrude (nee Hoffmann), death registration from Berlin, Germany

For those records not in the FHL system, using your skills with Meyers Gazetteer (see chapter five) to determine which Standesamt has or had original jurisdiction over the records is most important. As previously noted, the place of residence might not be the same as the place where the parish or civil registry was kept. (This is especially true in eastern Germany, where the population was smaller and the civil registry districts covered larger areas and included more towns than in the west. Also keep in mind that civil registry district and church parish boundaries are not likely to line up.)

The Meyers Gazetteer also contains maps and street indexes for larger cities in Germany, so an exact address will help track down the correct Standesamt. If you don’t have an exact address, write to the library in the city you’re researching to see if there are city directories available for the time period you’re researching. For example, Berlin city directories from 1799 to 1943 have been made available digitally by its library, the Zentral- und Landesbibliothek Berlin at <www.zlb.de/besondere-angebote/berliner-adressbuecher.html>. Use ProGenealogists’s conversion table and listing of the current Standesamt addresses <www.progenealogists.com/germany> to translate an address found in the city directories.

If you are going to research in person, generally there are indexes available to help track down the exact pages of the register on which the event in question can be found. Of course, traveling to Germany to research in person may not be possible for you. In this case you will still want to find the exact location of the records you need and then contact the archive that has the record to request it send a copy to you. The staff archivist will fulfill your request, though it may take some time. You’ll generally receive a quick response if you have a general query asking for confirmation of the types of records they have (in terms of places and time periods you are seeking). However, if you request a specific record you may have a bit of a wait. You’ll typically receive an acknowledgment of your specific request within a week, but the copies of the documents you requested will come weeks or months later. In most cases, the archivists will do the work first and bill you; fees vary by each state but can be as high as fifteen dollars a document. Some archives will send electronic versions of the documents as e-mail attachments instead of sending paper copies. The appendices include a sample request letter that you can copy and send to a German archivist. You’ll find the letter written in both German and English. More and more German archivists are now using e-mail (in which case you can simply send the a version of the sample letter in this book as an e-mail), especially for initial communications to ensure the archive has the requested record set.

Be aware that archivists often use international extract forms to fill records requests they receive from people who live foreign countries. Not all the information present in the original record may be copied onto the extract form. For example, marginal notes as well as other details from the record (such as parents’ names and residences in marriage records) may not be hand copied. If you are writing for a registration, courteously stress that you are requesting all information, even marginal notes.

Until recently, the empire-wide civil registration records were subject to privacy laws that limited release of the information to the person for whom the record was created as well as his or her parents, siblings, and direct descendants. Those who conducted research in Germany were required to sign a form stating that they would only look for information on direct-line ancestors.

Fortunately this situation changed with the implementation of Das Personenstandsrechtsreformgesetz (Civil Registration Reform Act), which turned the documents into public records available to anyone after the expiration of various blackout periods. The blackout periods for births is 110 years, 80 years for marriages, and 30 years for deaths. The old privacy restrictions still apply to records that fall within the blackout periods, unless it can be proven that all “participating parties” (child and parents for a birth record; both spouses for a marriage) have been deceased for at least thirty years.

In addition, the law also states that records that are now considered public due to age will be moved to the appropriate archives (Staatsarchiv or Kreisarchiv), which is also important because otherwise the records stayed only in each town in the Standesamt (registry office). You’ll find that both before and after the passage of the reform act, the stringency with which archivists enforce moving public records to Staatsarchiv or Kreisarchiv will vary from office to office. When you write to an archive or Standesamt for records, be sure to clearly state your relationship to the individual named in the records.