The Campaign

After the dress rehearsal at the 2002 parliamentary elections, it seemed likely that the crucial presidential contest in 2004 would be a two-horse race between Yushchenko and whomever the authorities decided to put up. So it proved, though this chapter will also look at some of the other players and some of the possible scenarios that were missed. Paradoxically, Yanukovych was a bad choice who almost won.

Yushchenko Flat-lining

Every revolution has its moderate and its radical wing. In spring 2004, no one called Viktor Yushchenko a revolutionary. Since 2001, had kept his distance from Tymoshenko's constant campaigning to force Kuchma out of office. Personally, Yushchenko was often disorganised and lazy; politically, he was cautious. He believed that the constant demonising of the old order was what kept the old opposition in opposition, and that the authorities would allow him to come to power by constitutional methods. And this included Kuchma, whom critics accused Yushchenko of toadying to in private, focusing especially on a notorious reference to him as his political ‘father’.1 This was, of course, unfair. Yushchenko knew that Kuchma's favourite political tactic was to balance all the main groups around him, and that if he could stay in that particular magical circle, he would be part of that balance. Ukraine needed to avoid the fate of Belarus, or even Russia, where the opposition had been cast into outer darkness, and the only apparent political choices were autocracy or implosion.

Yushchenko had led the opinion polls for two years, consistently scoring around 23 to 26 per cent – in other words, keeping the support Our Ukraine had won in 2002, but not advancing on it. Rumours of factional struggle and dissatisfaction in his staff were rife, especially with so many formerly separate parties making up the coalition. Paradoxically, problems were also caused by Yushchenko's success in winning (mainly small and medium) business support. Not all of the money was wisely spent, although the Yushchenko campaign was spared the financial bacchanalia that was apparent on the other side (see pages 120–1 and 156–7). In July 2004, Roman Bezsmertnyi was suddenly demoted from being Yushchenko's campaign chief and made ‘head of campaign staff’. Bezsmertnyi was increasingly disliked by the Our Ukraine businessmen, who stood to lose everything if Yushchenko went down, although Zhvaniia, his number one backer, stayed loyal, keeping him in a degree of favour. The agreement with Tymoshenko (see below) also led to pressure to up Our Ukraine's game, with Tymoshenko at one point even proposing herself as chief of campaign staff.

However, Yushchenko's natural caution led him to replace one regime turncoat with another: Oleksandr Zinchenko. Zinchenko's father, appropriately or not, had worked in KGB counter-intelligence. Young Oleksandr had himself worked as a censor for Komsomolskaia pravda, before becoming a typical komsomol businessman. He returned to Ukraine from Moscow in the early 1990s and moved in SDPU(o) circles, helping to set up their Inter TV channel in 1995, which became a notorious source of black PR against Yushchenko in 2002. The Melnychenko tapes illuminate Zinchenko's paradoxical position as head of the Committee on Freedom of Information, as he agrees with Kuchma in private that there is far too much freedom of information in Ukraine. Zinchenko complains specifically, ‘there's one thing I didn't like: how quickly they [the opposition] succeeded in forcing public opinion to divide the country, relatively speaking, that Surkis and Medvedchuk are oligarchs and Yushchenko and Tymoshenko are not oligarchs’.2 After the 2002 elections, when Zinchenko was elected deputy chair of the Rada, however, he quarrelled increasingly frequently with Medvedchuk, especially over the politicisation of Inter, and began to feel the heat on his business interests. In September 2003 he was expelled from the SDPU(o) and was ready to jump ship – though clearly he changed sides very late indeed.

Zinchenko made little organisational difference to Yushchenko's campaign, but he provided a certain spark. One faction in the Yushchenko camp, particularly Mykola Tomenko and Borys Tarasiuk, wanted to keep Yushchenko ‘pure’. They worried that cooperating too closely with Tymoshenko would encourage the authorities to paint her as black as possible and damn Yushchenko by association. They also worried that Oleksandr Moroz, as another possible ally, was still too close to the Communists and that his Socialist Party had still to reform its party ideology. Zinchenko persuaded Yushchenko otherwise. He was less concerned than Bezsmertnyi about links with radicals, and by the summer of 2004 the Yushchenko campaign was reaching out to both Tymoshenko and new student groups such as Pora (see page 74). A potential broader coalition was shuffling into shape. Organisationally, however, there were still problems. On the ground in eastern and southern Ukraine, the Yushchenko campaign existed only on paper. Its representatives on the local election commissions would be easy prey for the authorities' ‘administrative pressure’.3 They would be able to give detailed reports of the eventual election fraud, but would be able to do nothing to stop it.

Why Orange?

Like the British Labour Party after eighteen years out of power between 1979 and 1997, the Ukrainian opposition knew it had to reinvent itself. More exactly, its pragmatic wing was prepared to pay the price of reinvention, but its other wing preferred to remain pure in opposition. First of all, the slogan of the Orange Revolution seeded the idea that Ukraine could have its own version of ‘velvet revolution’ (as in Czechoslovakia in 1989), ‘singing revolution’ (the Baltic states, 1991) or ‘rose revolution’ (Georgia in 2003). (Kuchma's coterie labelled their takeover of parliament in January 2000 the ‘velvet revolution’, but the phrase never really stuck because it wasn't exactly revolutionary and it was mainly achieved with bribes.) Orange was chosen as the opposition's colour partly because the decisive phase of the election was expected to be the build-up to the first round of voting in October, when Kiev's main street, Khreshchatyk (the name means ‘crossroads’, and the street is the site of an ancient spring ravine) is lined with horse chestnuts and autumnal leaves. By the time the world's cameras focused on the actual revolution, however, it was mid-winter, and all the natural orange had gone.

Second, Ukraine's national colours are blue and yellow (symbolising sky over corn). These are now the official colours of the state and the state flag, but at demonstrations they tend to be monopolised by the ‘national-democratic’ opposition, which in the 1990s kept losing elections. In the Donbas, the Soviet propaganda stereotype, which narrowly associates the colours with the wartime OUN, rather than with the Ukrainian People's Republic of 1918 or the west Ukrainians' participation in the ‘Springtime of Nations’ in 1848 (when the flag was also flown), still holds sway. When Rukh concentrated mainly on a cultural agenda – broadening the use of the Ukrainian language in particular – no more than 20 to 25 per cent of the electorate voted for it. Some initial attempts were made at the 1998 Rada elections to broaden Rukh's appeal and lead it out of the culturological ghetto, with some very personal ads for Viacheslav Chornovil and a strong anti-corruption emphasis in Rukh's main slogan ‘Power to the People, Bandits to Prison!’, but it was only the economic achievements of the Yushchenko government in 1999–2001 that really laid the basis for reinvention. The national colours of blue and yellow were therefore kept in the background in 2004 (as even more so were the red and black also once favoured by the OUN), and orange came to the fore. The idea was to emphasise an all-national, value-based campaign, which was overwhelmingly peaceful and a little bit jolly.

Orange was also the colour of Ukraine's second football team, Shakhtar Donetsk, the pride of east Ukraine, which was an irony, but also a minor factor in neutralising some opposition. Dynamo Kiev, on the other hand, usually play in blue and white (and sometimes yellow), which were Yanukovych's campaign colours. Ultimately, however, the choice of orange would have unforeseen consequence of overriding importance, landing Ukraine one of the modern world's most precious commodities – brand recognition.

The Radicals: Pora

Every revolution has its vanguard. A prominent role in the Ukrainian events would be played by the youth activist organisation Pora, which was actually made up of two organisations, one of which was deliberately not organised. Pora would provide the opposition with extra strength, compared to 2002, and was also symptomatic of its changing tactics. Pora was modelled on rough regional equivalents such as Serbia's Otpor (‘Resistance’) that helped bring down Slobodan Milošević in 2000, Georgia's Kmara! (‘Enough!’), which was prominent in the ‘Rose Revolution’ of 2003, and the rather less successful Zubr (‘Bison’) in Belarus, which had conspicuously failed to oust local desperado Aliaksandr Lukashenka in 2001. All three were youth movements of non-violent protest. Equally important, though less of an obvious parallel, were the lessons learnt from the Slovak equivalent OK'98, which had helped to bring down another semi-authoritarian strongman, Vladimír Mečiar, in 1998, by building an NGO coalition dedicated to combating election fraud and improving voter turnout. Pora was, however, also specifically Ukrainian. In Ukrainian, its name meant ‘It's Time’, i.e. it's time for the old guard to go; and also inverted the title of the patriotic hymn ‘Ne Pora’ (‘Now is Not The Time’, 1880) by the west Ukrainian writer Ivan Franko (1856–1916). It was much punchier than the name ‘Wave of Freedom’, which had been suggested at one time.

The first version of Pora, nicknamed ‘Black Pora’ after its black and white logo and headband, was a continuation of the radical wing of the unsuccessful ‘Ukraine Without Kuchma’ and ‘For Truth’ movements of 2001. Many of its activists were irreconcilables, permanent oppositionists, many from west Ukraine, several of whom had been on Muskie scholarships to the USA, who sat down and thought about how to avoid repeating the mistakes they had made in 2001.4 Black Pora's leading light was Mykhailo Svystovych, later editor of www.maidan.org.ua, but it remained deliberately leaderless and amorphous, mainly for ideological reasons, but also because a cell structure was its best defence against repressive measures by the authorities. The conspiratorial method was popular amongst the young. It also worked. Unlike its equivalents in 2001, Pora was not infiltrated by provocateurs, and the Orange Revolution passed off without a single broken window or baton charge.

Discussions about the group's strategy began in November 2003 and Black Pora made its first public appearance on 29 March 2004, the day the clocks changed in Ukraine, with a ticking clock, which was intended to mark out Kuchma's remaining time in office, as its symbol and a mysterious ‘What is Kuchmizm?’ sticker, inviting people to visit its irreverent website, www.kuchmizm.info. Two weeks later, their answers appeared on other stickers: ‘Kuchmizm is poverty’, ‘Kuchmizm is banditry’, ‘Kuchmizm is corruption’. ‘Yellow Pora’, whose de facto head was Vladislav Kaskiv, came up with many of the same ideas at the same time, appearing only slightly later with a yellow logo in which the letter ‘o’ appeared as a clock at fifteen minutes to midnight, and with the website www.pora.org.ua. ‘Yellow Pora’ were rather more entrepreneurial, both politically and economically, and more Kiev based. They were also more prepared to talk to the press – indeed that was part of their raison d'être. Black Pora had a strong negative message, but avoided being openly pro-Yushchenko, while Yellow Pora, on the other hand, were happier to work unofficially with the Yushchenko campaign. Yellow Pora flags began to appear at Yushchenko rallies. Roman Bezsmertnyi helped coordinate, if not control, their actions, and a useful division of labour would be established during the protests on the Maidan, with two informal ‘agreements’ on 15 October and 15 November on a division of labour. There were even suspicions that Yushchenko's headquarters had helped set up the ‘copycat’ Yellow Pora to steal the brand and steer it more in his own direction. Some of its web material did seem to be copied from the Black Pora group.

The two Poras held a unification congress of sorts on 19 August 2004.5 Their joint membership was necessarily imprecise, but estimates of about 20,000 seemed about right. Both versions of Pora provided three novel strands in their approach. The first was gleaned from the book by the Amercan Gene Sharp, From Dictatorship to Democracy: A Conceptual Framework for Liberation (1993), which had also been popular in Serbia in 2000. Sharp, dubbed the ‘Clausewitz of non-violent warfare’, has since the 1960s advocated ‘strategic non-violence’, which is neither passive nor a means of avoiding conflict, but a means of identifying and engaging with the weak points that any regime will have. It is not money, he argues, but a change in mindset that is crucial to bringing about change. Moral confidence is an opposition's most important asset, especially in encouraging the thousands of foot soldiers, who support any establishment, to defect.

The second element was the use of ‘Situationist’ tactics designed to mock the authorities and dispel the fear of repression. These included the ticking clock, posters of a jackboot crushing a beetle, the slogan ‘Kill the TV Within Yourself’ and carnival-like street parades, intended to block the buses used to ferry ‘professional voters’ to the ballot box on polling day. Pora also put out a satirical paper, Pro Ya. i tse, ‘About Ya[nukovych] and Stuff’. Yaitse means ‘egg’, a reference to the comic egg attack on Yanukovych in September 2004 (see page 99). The third element, copied from Slovakia in 1998 but now transferred to the internet, was the development of an NGO network to combat the regime's ‘administrative resources’. Pora certainly did not lead the development of the network, but was symptomatic of its growth and a key link in the organisational and internet chain. Back in 1999, Kaskiv had helped to found the ‘Freedom of Choice’ coalition of NGOs, which helped monitor and analyse the election, with a website at www.campaign.org.ua. It developed its role in 2002, and in 2004 benefited from astute financial support from the West (so there may have been some slippage of funds over to Pora). In this way, at least, Yellow Pora acted as a kind of ‘semi-official partner for the OSCE mission’.6 But it was very semi-official. With one or two minor exceptions, the OSCE maintained the very independence that Russia and the Yanukovych camp so disliked.

Another NGO was Znaiu (‘I know’, i.e. I know my rights), a more studiously neutral organisation set up to encourage people, especially the young, to vote (www.znayu.org.ua). According to Znaiu's leader, the twenty-eight year old Dmytro Potekhin, his group won a $650,000 grant from the US-Ukraine Foundation, with an extra $350,000 for the third round, topped up by $50,000 from Freedom House.7 The money went on ten million leaflets, a toll-free helpline and ads in various papers explaining voters' rights. It also paid for visits by incoming US congressmen. Twelve thousand copies of the Sharp book were published with money from his Albert Einstein Institute and distributed through www.maidan.org.ua. Znaiu avoided anything that smacked of political campaigning, but was happy for Black Pora, at least, to deliver its ‘negative message’ on the dangers of fraud.

Some have cast doubt on the effectiveness of Pora before the protest campaign proper.8 It activated students, but not the wider numbers who were to be outraged by the electoral fraud that provided the revolution's key spark. It overlapped with other smaller groups seeking to perform similar tasks, so that the youth movement actually became somewhat fragmented. These included Chysta Ukraïna (Clean Ukraine, www.chysto.com, with a paper, Za chystu Ukraïnu!), Student Wave, Sprotyv (Resistance) and Student Choose Freely. Nevertheless, the regime considered Pora a big enough threat to plan active measures against it.

The procurator Hennadii Vasyliev led a secret group plotting against Pora and related NGOs. The group included his deputy, Viktor Kudriavtsev, the Kiev police chief, Oleksandr Milenin, Mykhailo Manin (deputy minister) from the interior ministry, and Ihor Smeshko from the SBU. On 15 October, the police raided the Kiev office of Pora, supposedly finding a homemade explosive device, 2.4 kilograms of TNT, electric detonators, and a grenade, even though Pora members videotaped them and their sniffer dogs leaving empty-handed, forcing them to come back later when no one was around. Pora claims 150 people were detained nationally, and fifteen charged, including one ‘leader’, Yaroslav Hodunok of the Ukrainian People's Party. On 22 October, agents raided the apartment of Mykhailo Svystovych, in connection with the alleged discovery of explosives. Kudriavtsev also convened a secret meeting of the SBU and interior ministry in October, where plans were made to arrest up to 350 Pora and other student activists three days before the first round, and plant them with drugs and forged money – but the plan met with ‘silent protest and open sabotage’.9

Yushchenko's Allies: Attempts at Divide-and-Rule

The 2002 elections had caught the authorities in a pincer movement. In total contrast to 1999, when nearly all the regime's real opponents had been substituted by fakes, the authorities had faced three real opposition parties, and its efforts against them had proved divided and weak. In 2004, it was the opposition parties who were determined to be the ones playing divide-and-rule.

Given her ambiguous role when first entering politics in 1997–9, a number of the regime's advisers initially thought Tymoshenko could be scared or bought off, while others suggested that she could be manipulated into standing on her own, to take votes off Yushchenko. Both factions assumed that the constant black PR and legal pressure they placed her under throughout 2002–4 would destroy her campaign. They even created two whole websites devoted to besmirching Tymoshenko's name: www.aznews.narod.ru and http://timoshenkogate.narod.ru. However, a series of planned killer blows had little effect. In May 2004, Volodymyr Borovko, an alleged SBU agent in her party, provided the authorities with a video tape on which Tymoshenko apparently discussed the possibility of bribing a judge with $125,000 to secure the release of her four arrested colleagues from United Energy Systems (see pages 22–3). In September, Russia weighed in with charges against her – a measure supposedly agreed in private between Medvedchuk and his Kremlin counterparts, first Aleksandr Voloshin then Dmitrii Medvedev. Tymoshenko's more radical statements were constantly replayed in the official media, the most notorious of these being the comment that, ‘Donetsk should be fenced off with barbed wire’ – which she, of course, claimed never to have said.

This all seemed to have the opposite effect to the one intended, largely because Tymoshenko decided that she would be destroyed unless the regime could be brought down. The more the authorities campaigned against her, therefore, the more she campaigned against them. Tymoshenko knew how to fight dirty, and was often a better Bolshevik than them all. She also knew when it was time to play it clean (at least in public). On 2 July 2004, she formally declared she would not run in the election and signed a deal with Yushchenko under the heading ‘Force of the People’ – not a formal coalition as such, as Tymoshenko agreed to back Yushchenko, but a declaration of unity and a division of campaigning responsibilities. Tymoshenko had won 7.3 per cent of the vote in 2002. Now that she was on board, Yushchenko's rating (23.6 per cent in 2002) moved consistently over 30 per cent. On the other hand, the agreement missed an opportunity to combine the efforts of the various campaign teams in the most effective way. Tymoshenko was supposed to campaign in the eastern oblasts, where her efforts were largely wasted. Not only did Tymoshenko remain steadfast, however, but in private she was playing the same game of divide-and-rule as the authorities, making a series of secret contacts with the Donetsk clan, including Rinat Akhmetov, with old enemies such as Viktor Pinchuk and with the SBU – in short with anyone who had their doubts about Yanukovych.10

The authorities began to have greater hopes that they could manipulate Oleksandr Moroz's Socialist Party. The Socialists are one of the few parties in Ukraine with a real grass-roots structure. Our Ukraine therefore hoped to cooperate with the Socialists in central Ukraine, where they were weaker and the Socialists correspondingly stronger. From the opposite perspective, the powers-that-be sought to use the Socialists to block off Yushchenko's growing popularity in central Ukraine. It also made perfect sense for them to negotiate with the Socialists, as the moderate opposition, to try and preserve certain interests. Crucially, the Socialist leader, Oleksandr Moroz, had long been personally committed to the idea of constitutional reform.

In February 2004, a secret plan to exploit the Socialists, drawn up by the Russian ‘political technologists’ advising the regime, found its way on to the web.11 Unfortunately, this time there was more of a bite at the bait. According to the main authority on the Ukrainian left, the Socialists in 2004 were ‘not interested enough in ideology and were too often engaged in intrigue’.12 It was certainly true that the party had shadowy business interests to protect. Its major sponsor, Mykola Rudkovskyi, had interests in an oil well in Poltava, and had also helped the fugitive Melnychenko. The party had at one time had many more sponsors, including the eventual deputy head of the Security Services, Volodymyr Satsiuk (see page 98), but most were scared off in 1999. The party also had its share of ambitious individuals, such as its campaign chief Iosyp Vinskyi, who maintained private contacts with Medvedchuk and consistently opposed cooperating too closely with Yushchenko or Tymoshenko. Both Vinskyi and Rudkovskyi argued that, as the party gradually evolved towards European-style social-democracy, this would move it closer to the fake social-democracy of the SDPU(o). However, more sensible voices, such as Yurii Lutsenko, one of the key organisers of the Ukraine Without Kuchma campaign in 2001, knew that such development should take the party closer to the real opposition instead. The party had one eye on the next parliamentary elections in 2006, for which it hoped to receive friendlier coverage on SDPU(o)-controlled TV. The Socialists were also interested in money, and took plenty from the SDPU(o) before the first round.13 The leaked plan actually intimated that Moroz could be levered into the presidency, gratefully to serve his masters' interests thereafter – which was never likely.14 On the other hand, in December the party would return to the game of constitutional reform favoured by Medvedchuk, though it is unclear how much of a victory for him this ultimately was (i.e. fixing the constitution in case Yushchenko came to power – see pages 80–1). After the elections, the Socialists were happy to see Medvedchuk's party collapse. In other words, they took the money and ran.

The one party the regime could rely on was the Communists. They had never really been an opposition party, in any case, and Tymoshenko, and even Moroz, on occasion, quite rightly didn't trust them. Their leadership was also corrupt, particularly the older generation ‘inner party’ that stood behind the formal party leader, Petro Symonenko. Stanislav Hurenko, for instance, who had last been leader of the old party back in 1990–1, was still around and had good private relations with his former aide-de-camp, the chair of parliament, Volodymyr Lytvyn. The Communists were also privately close to the Donetsk clan, to whom they had lent their parliamentary lobbying skills to develop their various business scams in the 1990s. So complicit were they in fact that, although Symonenko formally ran in 2004, the Communist leadership was prepared to acquiesce in a highly risky opt-out from actually campaigning. Without the Communist ‘gift’ of 15 per cent (the party's 20 per cent vote in 2002 collapsed to 5 per cent this time), Yanukovych's campaign would never have got off the ground.

The Authorities' Options

Option One: Changing the Rules, Constitutional Reform

One of the great ironies of the Orange Revolution is that the authorities might possibly have won the election if they had used different methods. However, there were too many players on their side, too many cooks with too many plans, and they ultimately ended up working against one another.

The first plan, which was much discussed after a fatuous ruling by the Constitutional Court in December 2003 that cleared the way for a Kuchma third term, was to repeat the election steal of 1999. (The Ukrainian Constitution says ‘one and the same person shall not be the president of Ukraine for more than two consecutive terms’. As it was passed in 1996, however, the court's Kuchma appointees argued that his original election in 1994 was governed by the 1991 Law on the Presidency instead, despite the fact that its wording is not much different: ‘one and the same person shall not be the president of the [then] Ukrainian SSR for more than two consecutive terms’. Some lawyers thought the ruling opened the interesting question of just who had been president between 1994 and 1999.) Kuchma, however, had a health scare at this time, and besides, with his ratings at rock bottom, at less than 5 per cent, it was difficult to see how he could claim another win except by the crudest of frauds.

Some members of the established regime argued that the whole controversy was a feint on Kuchma's part, a characteristic ‘lesser evil’ ploy, designed to frighten moderate deputies into backing constitutional reform (see below), and moderate voters into backing some possible ‘third force’, which, bizarrely, Kuchma thought again could be himself, in a different guise. One secret plan, leaked in June 2004 but supposedly drawn up in November 2003, was labelled ‘Kuchma's Third Term: How it Should Be’.15 It envisaged creating ‘directed chaos’, setting Yanukovych against Yushchenko, and east Ukraine against west, so that the elections could be cancelled to restore ‘order’, and Kuchma's term promulgated as a ‘lesser evil’. Clearly, this was intended to be a serious option, as the election did indeed end up polarised in this way, and Kuchma began to pose as a conciliator in December. It is also true that Kuchma himself seems never to have quite liked or trusted Yanukovych. His characteristic ploy of divide-and-rule would be under threat if the Donetsk clan came to unrestricted power. Yet another document, leaked later in 2004, explicitly stated that political reform would ease the fear of ‘Donetsk authoritarianism’ and muscular business expansion after the election.16

Kuchma was simply deluding himself. He may have given up on the rest of the world in the years of semi-isolation since the Gongadze scandal broke in 2000, but the people around him had not. Stealing the election too blatantly would damage their hopes of rehabilitation in the West. The preferred option of Viktor Medvedchuk, Kuchma's chief of staff, was therefore to change the rules so radically as to deprive any incoming president of real power. It was perhaps natural for him to think in such terms, as no one ever thought of Medvedchuk himself as having any electoral appeal. Medvedchuk had business interests to protect from the Donetsk clan, and was therefore not particularly enamoured of Yanukovych. The two men's forceful personalities also led to many a private clash.

The Rada spent much of the first half of 2004 locked in struggle over the project of constitutional ‘reform’ which was sponsored by Medvedchuk and, with sufficient prompting, the Communists. There were many overlapping proposals, but they all included different ways of reducing the power of the next president. One plan was to delay the presidential election until the following parliamentary elections due in March 2006. Another was for the Rada, not the people, to select the next president in Autumn 2004 (300 out of 450 votes would be necessary) and extend its own four-year term an extra year, until 2007. The third plan envisaged the 2004 presidential and 2006 parliamentary elections going ahead as planned, but under new terms, whereby the 2006 parliament would be elected for five years rather than for four, and would have the right to select a new president, who would serve for five years until 2011. Whoever was (popularly) elected in November 2004 would therefore have a very short term before parliament voted for a successor within three months of its election in March 2006 – although in theory the ‘2004 president’ could take part in that vote.

Whatever the detail – and there was a lot of it – and the sophistry of arguments deployed in support of the plan, this was just plain cheating. Yushchenko was the favourite to win, and Medvedchuk was simply trying to deny him the fruits of victory. When the plan was discussed in parliament, it was particularly galling to listen to the old guard lecturing the opposition on the dangers of authoritarian rule. The final package failed in a dramatic vote on 8 April, only six votes short of the necessary two-thirds' majority (294 instead of 300 deputies out of 450 voted in favour of it). Despite massive pressure from Medvedchuk and, according to Volodymyr Lytvyn, the chair of parliament, at least five falsified votes, the proposal failed because several reluctant ‘oligarchs’ refused to support it,17 including Oleksandr Volkov, Derkach father and son, the former mayor of Uzhhorod, Serhii Ratushniak18 and Volodymyr Syvkovych, an associate of the Russian businessman Konstantin Grigorishin. Some of these men clearly disliked Medvedchuk and had other plans in mind.

The opposition had something to celebrate at last. Nevertheless, even after his setback in April, Medvedchuk hoped to re-animate the issue on the eve of the vote, even, possibly, between the first and second rounds. He was stymied because the authorities' artificial ‘majority’ in the Rada fell apart in September. Three factions suspended their allegiance: the so-called Centre; the People's Agrarians; and Democratic Initiatives – the latter not because of any point of principle, but because its fancy name was a mask for the Kharkiv ‘clan’, who objected to the pooling of the state's shares in two oil companies, Halychnya and Tatnafta, to a third company, Ukranafta, a deal that basically benefited the rival Privat group from Dnipropetrovsk. The deal unravelled, and the majority reravelled. A deal on the Constitution was eventually done, in December. But its apparent failure at this time was one reason why some of Yushchenko's opponents decided to poison him.

Option Two: A Strategy of Tension

The authorities also toyed with the idea of creating a ‘strategy of tension’, or ‘organised chaos’, either as a means of intimidating some voters and scaring others into supporting them, or as an excuse to delay or neuter the election, but they were too divided, or insufficiently ruthless, to push such a strategy to any extreme conclusion. On 20 August 2004, a bomb went off in the Troieshchyna market on the edge of Kiev, killing one person and injuring eleven. It was followed by a smaller bomb two weeks later.19 The attacks were immediately blamed on extremist supporters of Yushchenko – though what motive they would have had for such an unprovoked attack was far from clear. Troieshchyna was actually the stomping ground of the gangster Kysel and of various shadowy rackets linked to Medvedchuk, and three of those arrested were later found to work for the fake nationalist parties secretly funded by the authorities (see below).20 In December, many of the charges against those arrested would be withdrawn.21 Bombs were also planted on the premises of the student movement Pora. Alarms started ringing when Yevhen Marchuk, the relatively neutral minister of defence, was dismissed in October.

On 23 October, an estimated 100,000 rallied peacefully in Kiev outside the headquarters of the CEC, to demand it conduct a fair election. Ignoring such disappointing restraint, the authorities staged a double provocation: first a violent ‘assault’ by Yushchenko ‘supporters’ on the building itself, then, later that evening, an ‘attack on the militia’ that seems mainly to have been carried out by other militia in plain clothes.

This was on the whole lower-grade provocation, which mainly served as black PR, and to keep the opposition disoriented. But there was always the temptation to do more. Towards the end of the campaign, Andrii Kliuiev wanted to organise fake terrorist attacks in the Donbas, with dozens of deaths that could be blamed on Yushchenko, but the SBU refused to cooperate with this plan, and likewise the interior ministry's special forces. Even established organised crime structures refused to have anything to do with it.22 The younger Kliuiev was the acknowledged paymaster for ‘incidents’ such as the trouble outside the CEC on 23 October.23 These types of measures were always in the background, part of the attempt to intimidate the opposition and keep its options narrow; they were essentially part of the game of bluff. It is in this light that later measures, including the miners' demonstrations, the movement of Crimean troops, and the threat of ‘separatism’, should really be seen (see pages 133–4 and 145–6). Overall, however, the opposition was not intimidated by the measures the regime took, and anything more extreme carried too high a cost for most elements in the establishment, all with one eye on their survival strategies, to consider seriously.

A different type of provocation was organised during the mayoral elections held in the west Ukrainian town of Mukachevo, Transcarpathia, in April 2004. Thugs were deployed and ballot boxes stolen to reverse the result. The Our Ukraine candidate, Viktor Baloha, claimed 19,385 votes (57 per cent) against the 13,848 won by the SDPU(o)'s Ernest Nuser. An exit poll gave Baloha 62 per cent.24 Baloha was therefore distinctly surprised to lose by 12,297 votes to 17,416 in the official count. No less than 6,307 local voters were also surprised to find that their votes were now invalid. These events were designed to test the limits of achievable fraud, and to demotivate voters by showing them that their voices would not be heard. Fortunately, the level of international protest was for once relatively strong.

Option Three: Yanukovych the Populist

The third option for the established regime was to concentrate on the actual election. To do this, the authorities needed an agreed candidate, but it is not clear why they chose Yanukovych. A more centrist candidate could have been sold to the electorate much more easily, as could a candidate without a criminal past, or someone who had occupied a post more prestigious than, as Yanykovych, a driver in the Soviet era. (Kuchma, for instance, it will be recalled, had headed the giant missile factory Pivdenmash.) Someone less renowned for his or her ability to speak both Russian and Ukrainian equally badly would have also been a better choice – Yanukovych would famously misspell his own job title and qualifications in his official application to stand in the election.25

It seems, however, that in November 2002, the up-and-coming Donetsk clan simply informed a president much weakened by the Gongadze affair that it was their turn to nominate the prime minister. Many of the other ‘clans’ were clearly less than keen on this idea. Yanukovych scraped together only 234 votes (he needed 225 out of 450 to be approved), some of which cost up to $200,000 to obtain.26 This may also have been a financial proposition as far as the president was concerned, but, more importantly, it suited Kuchma's main priority of providing a counterbalance to the power of the SDPU(o), that is, the Kiev clan, whose leader, Viktor Medvedchuk, now headed the presidential administration, and was able to count the outgoing prime minister, Anatolii Kinakh, as his informal ally. The SDPU(o) was happy to cede the premiership to forestall what they thought was the greater danger (though in the light of later events, this now seems deeply ironic) of the Donetsk group forging some kind of alliance of convenience with Yushchenko. (The Donetsk group, which actually produces things and depends on foreign trade for its profits, temporarily considered that Yushchenko might front their operations. The SDPU(o), however, prefers empire-building within the state and mass media; a semi-isolted Ukraine therefore suited these purposes.) Yanukovych's transfer to Kiev also left Rinat Akhmetov more clearly in local control of Donetsk. He was therefore happy to stop making overtures to Yushchenko and cough up the cash for the cut-price privatisation of Ukraine's biggest steel company, Kryvorizhstal, in 2004.27

There was some discussion of replacing Yanukovych as prime minister and therefore most-likely candidate in December 2003, but the Donetsk clan held firm. Thereafter, the regime had too little time to launch any alternative. The Donetsk clan was thinking narrowly about expanding its own business and political interests, and not strategically about the type of candidate best placed to win the election. They also vastly underestimated the difficulties that their thuggish political culture would have in translating to the rest of Ukraine, and even to the rest of east Ukraine. The latter factor may explain why the possible ‘centrist’ candidates, particularly Serhii Tihipko, the new head of the National Bank, took fright. Tihipko had grown into his own PR image as an urbane international capitalist equally at home in international playgrounds such as Davos in Switzerland, as in his home city of Dnipropetrovsk, and was put off running if he had to use Donetsk-type ‘technology’ to do so. Conversely, Tihipko's white collar image did not sell him to voters in the Donbas. He ended up as Yanukovych's campaign manager instead.

Other possible centrists also had their weaknesses. The economy minister, Valerii Khoroshkovskyi, was too young; the Odesa governor, Serhii Hrynevetskyi, too obscure. The most interesting candidate might have been the Rada chair, Volodymyr Lytvyn, but as he figured in damning portions of the Melnychenko tapes, his survival strategy depended on his continued control of parliament. Certainly, a campaign fronted by someone such as Tihipko or Lytvyn would have been very different, but so many other factors would have changed as a result – a stronger Communist vote would have been likely without Yanukovych, for instance – that it would be rash to say more. But the authorities' advisers certainly missed a trick. They did not do what this seasoned cynical observer expected them to do in 2002–4, which was to box Yushchenko in by running strong flanking candidates on both his right and centre-left. The choice of Yanukovych, the centripetal candidate, failed to cut off the opposition's advance towards newer, softer voters in central Ukraine.

Another possible reason for the regime's backing of Yanukovych is that the constitutional reform package was designed partly with him in mind, and that he was a pliable candidate behind whom Kuchma could continue to exercise power after 2004. (Yanukovych certainly wasn't the sharpest tool in the box, so this may have worked.) Another theory is that the choice of an east Ukrainian was dictated by the campaign strategy prepared by the Russian ‘political technologists’ (see below). In the years of diplomatic semi-isolation since the breaking of the Gongadze scandal in 2000, Kuchma's regime had fallen under stronger Russian influence than would otherwise have been the case; and for the Russian ‘geopolitical project’, it made sense to choose the candidate who was as antithetical to west Ukrainian ‘nationalism’ as possible. Some Russians even hoped to provoke a simmering undercurrent of Galician (west Ukrainian) separatism, in order to build a stronger Russo-Ukrainian condominium without them. Rather more Russians had appreciated the advantages of a semi-isolated Ukraine and hoped that that trend would continue under Yanukovych. Attending to Russia's needs, however, was not the right way to appeal to the median Ukrainian voter.

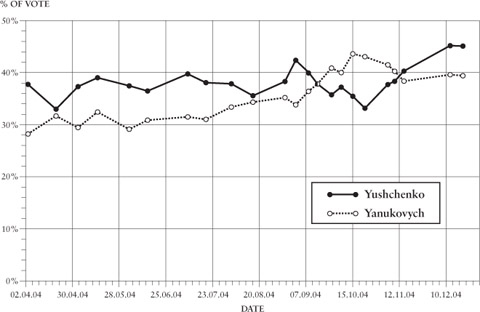

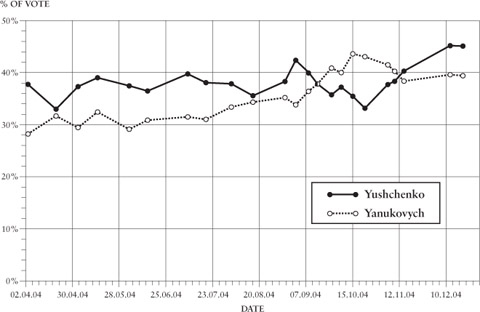

Opinion poll ratings of Yushchenko and Yanukovych in 2004, in an assumed second round.

Source: supplied by Valerii Khmelko, KIIS

It is also possible that the authorities just got it wrong. They were over-confident in their ability to sell anybody, and over-reliant on the ‘administrative resources’ they presumed would guarantee victory in any case. It is also likely that there is an element of truth in all these theories, and the cumulative effect was that the Yanukovych campaign lacked the clear direction it needed.

Although he himself was ‘white collar’, Serhii Tihipko, as Yanukovych's campaign manager, sought to craft a positive, populist campaign. For this strategy to work, however, Yanukovych should have adopted a more ‘oppositional’ image. His belated rhetoric about ‘old power’ (Kuchma) and ‘new power’ (himself) in December came far too late to make any real difference. After an initial rise in the polls in the spring, Yanukovych's progress was therefore stalled in the summer, with Yushchenko still ahead. Yanukovych himself grew dissatisfied. With three months to go, this created an opening for the Russian advisers, most of whom arrived in town around this time, to promote their chosen strategy. There was a great deal of uncertainty about the election at this point which, because it occurred so late in the day may have stimulated the attempt to kill Yushchenko. To bolster Yanukovych's popularity, the government planned huge increases in welfare payments, including a dramatic doubling of the state pension from UAH137 to UAH284 ($54), but had to delay these until September, as even then the rises would prove ruinously expensive. But the tactic proved temporarily effective. Yanukovych surged ahead in the polls, rising by ten points between mid-September and mid-October (from 34 per cent to 44 per cent in a putative second round). Factor analysis by the Kiev International Institute for Sociology (KIIS) suggests that three-fifths of Yanukovych's rise came from the over-fifties – those who were already on a pension, or who would be, in the near future.28 The pensions hike and the moves on the Russian language to appeal to relatively elderly Russophones (see below) reinforced one another, but the former came first, and Yanukovych's rise in the ratings immediately followed.29 On the other hand, the move revived popular fears of inflation from the 1990s.

Option Four: The Russian Card

Most of the Russians who arrived in Kiev in 2004 described themselves as ‘political technologists’. (I have explained this strange term elsewhere.30) The ‘political technologist’ is much more than a ‘spin doctor’ such as Peter Mandelson in the UK. The latter spins a story between its origin and its interpretation by the media. The political technologists who proliferate throughout the former USSR, however, like to think of themselves as political metaprogrammers, masters of the local political universe. First, the scope of their work is extremely broad. Countries such as Russia and Ukraine are often called ‘directed democracies’ (the Russian term is upravliaemaia demokratiia) and the job of the technologist is one of direction, shaping and even creating governing parties and politicians, and trying to do the same to the opposition, as well. Second, they dress up manipulation and fraud as ‘technology’, but their work is often corrosive and crude. They usually work for the authorities, and usually stop at nothing to win.

Ukrainians have two contradictory images of so-called political technologists. Often, they are feared as omnipotent; their schemes are seen as too clever to detect and too effective to oppose, and their cunning plans as always able to deliver another victory for the undeserving and dim-witted powers-that-be. On the other hand, fictional Russian political technologists make a brief appearance in Andrei Kurkov's novel Penguin Lost, and are depicted as feckless misanthropes, ‘bastards to a man’, with ‘such a taste for luxury.’ ‘There's hardly [a pre-prepared manifesto] we can't use three times over’, they declare. ‘The main thing is to clear off before the successful candidate starts implementing it.’ The ‘golden rule of the image maker is “Never be there for the result.” The client gives you hell if he loses, his rivals give you hell if he wins.’31 (Kurkov is Ukraine's most popular writer in translation, particularly big in Germany, thanks to his bleakly comic evocation of the seedier side of Kuchma's Ukraine.)

In reality, of course, some ‘technologists’ were good at their job, and some were not; but there was undoubtedly an over-supply of Russians working in Ukraine in 2004. The money was good, many were seconded by the Kremlin, and Russia had just finished its own election cycle, so a few had time on their hands. According to Andrei Riabov of the Moscow Carnegie Foundation, ‘Ukraine is a Klondike, an El Dorado … business is drying up at home’.32 (Putin's constitutional changes after the Beslan tragedy in September 2004, which abolished Duma constituencies and elected governors, meant there would be fewer elections to manipulate.) The most famous ‘technologist’ of all, Geleb Pavlovskii, of the Foundation for Effective Politics (FEP) in Moscow, was often in town, albeit claiming he was only working on a ‘Russian contract’ (i.e. for a client based in Russia). In one interview, he reeled off a long list of his colleagues: ‘Marat Gelman, Stanislav Belkovskii, Igor Mintusov, Sergei Dorenko … all became Kievites’ for the duration.33 Some, like Gelman, who had worked in Ukraine on and off since 2002, became over-familiar faces. Working in the dark was part of the secret of their success. Other frequent flyers to Kiev were Sergei Markov, Viacheslav Nikonov and Igor Shuvalov, who had worked for Kuchma in 1999 and, despite an expenses scandal, for the SDPU(o) and ‘liberal’ projects in 2002. Shuvalov had stayed on to oversee the so-called temnyky (weekly instructions to the media on how to cover – or not cover – events).

Kuchma's chief speechwriter and the deputy head of the presidential administration, Vasyl Baziv, complained that Gelman and Russian businessman Maksim Kurochkin, aka ‘Mad Max’, the director of Pavlovskii's Russia Club, which was based in the Premier Palace Hotel, Kiev's number one house of fun for the nouveaux riches, ‘made themselves at home’ at the presidential administration on Bankivska Street.34 The Russia Club was notorious for its dodgy finances,35 and the Premier Palace wasn't much better; it was widely assumed to be funded by circles close to the mayor of Moscow, Yurii Luzhkov, Russian businessman-politician Aleksandr Babakov (a friend of Gelman) and their Ukrainian associates, Hryhorii Surkis and Viktor Medvedchuk. In fact, the whole Yanukovych campaign was awash with money, and some were more interested in creaming it off. An apparent attempt on Kurochkin's life was made on 6 November, when a nearby Volkswagen exploded as he approached his car after midnight with two bodyguards. After the Orange Revolution he fled to Russia, just before the new authorities in Kiev accused him of fraudulent last-minute property deals involving the Dnipro Hotel in Kiev and three sanatoria in Crimea.

The Russians were almost all working for the Yanukovych side, although Gleb Pavlovskii was approached in September 2004 by the Our Ukraine financier, Petro ‘Poroshenko [who] made an open commercial proposition to cooperate with the Yushchenko team’.36 (Pavlovskii politely declined the intellectually challenging idea of working for both sides.) One interesting exception was Aleksei Sitnikov of the Moscow firm Image-Kontakt,37 who had also worked for Mikhail Saakashvili during Georgia's ‘Rose Revolution’ in 2003, allegedly advising him on the art of demonstration and virtual revolution (i.e. using the media to make it seem all ‘the people’ are on your side). Sitnikov didn't stay long, however.38 Sergei Markov also claimed that another leading Russian agency, the magnificently-named Nikkolo-M (the Russian spelling of Niccolo Machiavelli), was working for the Yushchenko side,39 but contacts again seem to have been only superficial. Minor roles were also played by Andrei Piontkovskii from Russia and Mirosław Czech from Poland.

The Russian political technologists had also been in Kiev, pushing up hotel prices, for the 2002 elections, when their work had mainly involved selling the establishment parties For A United Ukraine and the SDPU(o), and setting up the fake or ‘clone’ parties. Their earlier work was therefore only a partial success; their standard excuse the claim that, ‘the election's dynamic became who was for Kuchma and who was against – and we were squeezed in the middle’.40 If their analysis was correct, they faced a choice of tactics for 2004 – within their own limited repertoire, that is. One approach, more loosely associated with the faux-celebral Marat Gelman, in his other life a ‘post-modernist’ gallery owner, involved deconstructing the binary scenario that had tripped them up in 2002, by introducing a variety of ‘virtual objects’ to create the impression of a more complicated picture. These could be either stage-managed events designed to change the political atmosphere, or actual but virtual participants in the election, like the fake candidates and parties who had been more prominent in 1999 and 2002. The second approach, broadly more typical of Gleb Pavlovskii, who tended towards Russian great power nationalism, was to keep the polarisation scenario, but to change its dramaturgiia.

This is how they talked. What they meant was that they needed to reinvent the election's central theme. Instead of ‘good opposition’ versus ‘bad authorities’, it would have to be ‘east versus west’ within Ukraine. Pavlovskii and Markov therefore advocated playing the Russian card. It is not difficult to see why they thought this strategy would be a winner. First, they were Russian. Second, Putin enjoyed a very high approval rating in Ukraine – 60 per cent or more – and they thought they could craft the campaign in his shadow. Third, their sociological research (and they did do some solid work to justify their exorbitant fees) showed them that just over half the population used the Russian language as a first language, and their leading questions produced very negative images of ‘Ukrainian nationalists’ in eastern and southern Ukraine. An early try-out to test this theory in April 2004 had briefly pushed Yanukovych ahead in the polls. That month, the Ukrainian parliament had ratified the agreement on a Single Economic Space with Russia, Belarus and Kazakhstan, and, in a blatant provocation, the National Council on TV and Radio had announced that all channels would have to start broadcasting in Ukrainian. The nationalist wing in Our Ukraine fell into the trap, enthusiastically cheering the measure, which funnily enough was never implemented. Subsequent publicity about Yanukovych's criminal past and the events in Mukachevo meant the gain was only temporary (see figure on page 85).

Half the strategy was public. On 27 September, only a month before the vote, Yanukovych made a dramatic late commitment to make Russian an official language, to allow for dual citizenship of Ukraine and Russia, and to abandon all moves towards NATO (the first two would require specific changes to the 1996 Constitution, and none had been in his original manifesto). Russia waded in with help. During the Russian–Ukrainian summit in Sochi in August, Putin agreed to remove VAT on oil exports to Ukraine. Ukrainian petrol would therefore be 16 per cent cheaper, at a cost to the Russian budget of $800 million. Moreover, as crude price soared over $50 a barrel, Russian suppliers held prices constant in Ukraine till the election. There were also rumours that Kuchma had secretly promised to remove the Ukrainian fleet from the bases it shared with the Russian Black Sea Fleet (in Crimea, on Ukrainian territory since 1997) in return for Putin's support.41 Russia also announced, as of 1 November, that Ukrainians would be allowed to stay in Russia for up to ninety days without registering, and, from January 2005, would be granted freedom of entry into Russia with only their own domestic documentation.

The covert parts of the strategy can be seen in the plan leaked in June 2004, which was reportedly drawn up by Marat Gelman (see above). In private the technologists argued they could overcome the problems of 2002 if they were given freeer reign. The ‘main scenario for the campaign’, declared the report, must be ‘directed conflict’. ‘Our task is to destabilise the situation in the regions (maybe involving political games, but not the everyday economy)’, which might hurt the oligarchs' business interests, ‘and drag Yushchenko into this process.’ The report could not mention a potential conflict without suggesting it be exploited. It recommended stirring up animosity between Ukrainians from east and west; between Poles and Ukrainians; between Ukraine's various Churches; and between Slavs and Crimean Tatars. Overall, though, its preference was clear. ‘The task of the media [in other places, ‘our media’] is to interpret this as an ontological “East-West” conflict, a political conflict between Our Ukraine and the Party of the Regions, and a personal conflict between Yushchenko and Yanukovych.’42 The tone grew more impatient later in the campaign, when another leaked document urged ‘the escalation of confrontation on all possible lines: Galicia–East, South, West (USA–Europe) – Russia, Russian language, the threat of the growth of extremism, etc’. It also mentioned the need to ‘organise a social movement in the south-eastern regions of the country against Yushchenko and his circle coming to power, as a reactionary, Pro-American, radical candidate’ – and the need to depict the opposition as the ‘aggressive’ party.43

Unlike some other plans, which stayed on the drawing board, much of this came to pass. Trouble was only narrowly averted in Crimea in March, after nine Crimean Tatars were stabbed by skinheads. The Tatars were the ones who were then jailed for the offence. A blatantly political provocation followed in July 2004, when Serhii Kunitsyn, head of the local administration in Crimea, changed the local criminal code to create an offence of ‘squatting’, punishable by up to two years in prison. The Crimean Tatars had been deported en masse by Stalin in 1944 and not allowed to return until the late Gorbachev era. Most of the 260,000 or so who came back therefore lived in shanty-towns or self-builds, as their property was long gone. Kunitsyn now ordered several militia raids on Tatar areas, some allegedly using chemicals. The Crimean Tatars' traditional non-violent methods held with difficulty. A big majority voted for Yushchenko, but not in the disciplined unanimity of recent years, as some stayed at home in frustration with both their leadership and the general situation. Almost every Slav voter in the Crimea, however – that is, both Russians and Ukrainians – apparently backed Yanukovych. In the final round in December, 178,755 supported Yushchenko (15.4 per cent) and 942,210 (81.3 per cent) Yanukovych. As of 2002, the Crimean Tatar electorate was 186,000 (12 per cent of the total).44 The provocations also had a wider purpose, as the opposition, now led by Yushchenko, traditionally supported the Crimean Tatars: ‘Yushchenko must be represented as an enemy of Russians in Crimea’, the report argued, and of Slav culture in general. ‘If Ukraine can't defend the interests of Slavs in Crimea, then’ Yanukovych or ‘nearby Russia is always prepared to offer support’.45

One big problem with this overall strategy was that Yushchenko really wasn't a nationalist. Moreover, to his great credit, he refused the invitation to fight the election on such terms. The powers-that-be therefore covertly supported four virtual nationalists in his stead. All were previously obscure, but they were soon all over state TV acting out the role of the ‘nationalist threat’. All were secretly financed by the SDPU(o) and Yanukovych's party, which in public constantly used the wartime imagery of the OUN–UPA to demonise what it dubbed the nashisty (from the equation of ‘Our Ukraine’, Nasha Ukraïna, with fashisty).46 The fake four were a sorry bunch, however. Roman Kozak of the little-known OUN in Ukraine, was not the brightest of men. Dmytro Korchynskyi, an ‘intellectual provocateur’ on SDPU(o) TV,47 was over-exposed. The powers-that-be hoped that Andrii Chornovil, son of the veteran dissident they allegedly had murdered in 1999, would have inherited some of his father's charisma, but he hadn't. Bohdan Boiko, of the fake party ‘Rukh for Unity’, had a long record of political treachery and financial corruption in his native Ternopil, where he distinguished himself by speculating in the local sugar crop when head of the local council in the mid-1990s. Kozak, Korchynskyi and Kovalenko at the UNA were soon dubbed the Ukrainian ‘KKK’.

Still, they strove to damn Yushchenko by mock-association, demonstrating uninvited in his support and receiving plenty of coverage on official TV. Kozak's TV ads were even placed right before Yushchenko's, so that viewers could hear his call to ‘Vote for Yushchenko. Together … we will kick the Russians and Jews out of Ukraine!’ Kozak ended up spending the third highest sum on TV advertising. The four won only 0.35 per cent of the vote; but their constant over-exposure on east Ukrainian TV (Inter and 1 + 1), and their hysterically unrealistic calls to close Russian schools, ban the Russian language, and introduce a visa regime with Russia had a definite, if unquantifiable effect on building up anti-Yushchenko stereotypes in the east.

Nor were there many real nationalists for the authorities' PR machine to exploit, though there were some important exceptions. Clean Ukraine rather unwisely depicted Yanukovych as leading a gang of Yanuchary, a traditional nationalist insult for east Ukrainians. The ‘Yanuchary’ (in English, ‘Janissaries’) were soldiers in the service of the Ottoman Empire in Cossack times, traitors to their own faith and nation, who were press-ganged into service when young, made to forget their origin, converted to militant Islam and were often sent to raze their own villages to the ground (see plate 15).48 Ukrainian intellectuals published two open letters that did Yushchenko no favours by reverting to an older, more intemperate nationalist tone, attacking ‘“prime minister” Yanukovych [for] promising to grant the language of pop music and Russian criminal slang the absurd status of “second state language”’,49 and prejudging voters' rights by claiming that ‘today we have no right to give away a single Ukrainian vote to Yanukovych’.50

Three other ‘technical candidates’ were designed to ‘activate’ radical leftist and Russophile voters in east Ukraine, this time from their own side of the fence. Opinion polls showed that this segment of the electorate was disillusioned with the powers-that-be, but also susceptible to the black PR against both the West and west Ukraine. The technologists therefore argued it was better to use proxies to stimulate them into action. The technique was known as a ‘relay race’, with ‘technical’ (fake) candidates being paid to stir up anti-Yushchenko sentiment on the basis of crude anti-Western propaganda and then ‘pass it on’ to Yanukovych in round two, despite the risk that they would take votes from him in round one.51 Not only was the seemingly implausible Nataliia Vitrenko wheeled out to play this role (the fact that she could play it at all was testament to the degree of media control in the east, where part of the electorate had not been exposed to her exposure as a fake), she was joined by Oleksandr Yakovenko, leader of the faux-radical fake party, the Communist Party of Workers and Peasants (secretly funded by the Donetsk clan), and Oleksandr Bazyliuk of the justifiably obscure Slavic Party. The three dutifully hammered away at all the black PR themes prepared for Yanukovych, claiming that Yushchenko was an ‘ultranationalist’ and an ‘American puppet’, and that his wife was an ‘American spy’. The technologists seemed right: Vitrenko eventually won a useful 1.5 per cent and Yakovenko 0.78 per cent, though Bazyliuk flopped with 0.03 per cent.

The Orthodox Church of the Moscow Patriarchate played a similar proxy propaganda role – or, at least, one faction or ‘group of influence’ in its fairly pluralistic leadership did so. Despite wild talk that ‘the Donestkies must work on the Orthodox messianic idea if they want to strengthen their influence in Ukraine’, as the Donbas had originally been settled by frontiersmen-priests,52 most of east Ukraine was now dominated by post-Soviet agnosticism. Yanukovych's main backer, Rinat Akhmetov, was, in theory at least, a Muslim. (Most of the Russian political technologists were not exactly religious men.)53 On the other hand, as the Moscow Patriarchate was still technically part of the Russian Church, it was the most easily available institutional channel for Russian influence in Ukraine. Yushchenko was backed more informally by most of the two smaller Orthodox Churches, and by the Greek Catholics.

Both the Russian Patriarch Aleksei and Volodymyr (Sabodan), leader of the Moscow Patriarchate in Ukraine, blessed Yanukovych, the latter at Kiev's prestigious Caves Monastery. Volodymyr publically endorsed Yanukovych on UT1 TV on 10 November, stating that, ‘I view him as a true Orthodox believer, who would deserve to be the head of our state’.54 In November a typical stash of unsigned leaflets was found in a church near the Moldovan border attacking Yushchenko as ‘a partisan of the schismatics [that is, the rival Orthodox Churches] and an enemy of Orthodoxy’ and calling his wife a ‘CIA agent’.55 Priests politicised their sermons, and the Church's opaque finances helped channel several covert operations for Yanukovych (see page 109). The Church also helped the Yanukovych team send out flyers from no less than the Archangel Michael, the patron saint of Kiev, ‘with love’ from Yanukovych to his flock, but obviously implying divine endorsement for the prime minister (see plate 2). In return, the government handed the Patriarchate the St Volodymyr Cathedral in Crimea on the eve of the election.

Fortunately, as the Church was attacking one of its own, Patriarch Aleksei was prepared to make peace after the election, meeting Yushchenko on his visit to Moscow, and stressing that ‘we [now] respect the will of the people of Ukraine’.56

Russia

As one of Yanukovych's campaign slogans had it: ‘Ukraine – Russia; Stronger Together’. Putin obviously agreed, but there was still a real debate in both the Kremlin and the Russian press until September 2004, not about whom to support, but about whether to back Yanukovych exclusively or to take a more balanced approach. Putin's gamble on Yanukovych alone seems to have been a personal decision, albeit one prompted by Pavlovskii, Kuchma and above all by Viktor Medvedchuk, who loudly and repeatedly claimed he could deliver the necessary result. Putin's chief political fixer, Vladislav Surkov, deputy head of the Kremlin administration, convinced him that the same methods that had entrenched ‘directed democracy’ in Russia would work in Ukraine. Or rather, he didn't have to. Both men worked within the same set of assumptions, within a world view that saw their methods as omnipotent and any opposition as marginal.

One further problem for the Yushchenko camp was that its natural allies in Moscow, the Russian liberals, had tumbled out of the Duma in December 2003. Ironically or not, the Ukrainian opposition's message now came through two other channels. First were those Russian businessmen who had done well in Ukraine when Yushchenko was prime minister in 1999–2001. Not the controversial exiles such as Boris Berezovskii, but men like Oleg Deripaska, who had bought the Mykolaïv aluminium plant, Mikhail Fridman of the Alfa Group, who had bought the giant Lysychanskyi oil refinery, and Vagit Alekperov of Lukoil, who had bought the Odesa refinery and the Oriana caustic soda plant and set up a lucrative chain of petrol stations. In fact, some of them had done less well thereafter. Once Yanukovych was prime minister, the expansion of the Donetsk group had often been at the expense of opportunities for Russian investors. Overall, Russian investment was down an estimated 20 per cent. A second channel was through the Security Services. Oleh Rybachuk maintained this channel and claims it was open right to the very top, all the way through the campaign.57

Putin chose not to listen. He does not seem to have been thinking about economics, but about geopolitics. Once Ukraine was more firmly within Russia's orbit, then so many other things (the proposed ‘Single Economic Space’, Moldova, the South Caucasus, a more secure southern flank, an end to EU and NATO expansion, and even easier management of Belarus) would fall into place. Significantly, the end to debate in Russia coincided exactly with Yanukovych's declarations on the Russian language, dual citizenship, etc, on 27 September. Clearly, Putin, the former KGB apparatchik, had no time personally for Yanukovych, the former convict. The Ukrainian opposition, particularly its satirical wing, derived much succour and amusement from the scenes shown on Ukrainian TV during the Kiev military parade on 28 October, the eve of the first round, when Yanukovych, disrespectfully munching sweets, offered one to a clearly astonished and frankly disgusted Putin.

This was only the last of frequent-flyer Putin's many high-profile visits to Ukraine, because he was convinced his own popularity was an asset. He received extensive coverage on official Ukrainian TV, including a ninety-minute phone-in broadcast, live on three national channels on 26 October, when 80,000 questions were received, which was unprecedented in Ukraine (Kuchma hadn't faced a real voter for years). Putin wasn't necessarily wrong to assume that he was helping the campaign. One theory has it, however, that his support showed up Yanukovych's weaknesses, and made it too obvious even to those who felt culturally close to Russia that Yanukovych was politically dependent on the Kremlin (as did the bizarre idea of putting up Yanukovych billboards in Moscow). Despite this, others still insist he bolstered a flailing candidate. Whether or not this was true, Putin clearly erred massively in supporting Russian political technologists' methods. The most telling aspect of his message of congratulations to Yanukovych on Monday 22 November, the day after the second round vote, was that it could only have been based on their fraudulent exit polls, as the official result was not then out. Putin also misjudged the ability of the political technologists to guarantee victory, but then he was not alone in that.

Bushchenko

In October, when the outcome of the election still hung in the balance, the authorities' black PR against Yushchenko went into overdrive. Given the simultaneous presidential election in the USA, a new figure appeared in the campaign – ‘Viktor Bushchenko’ (Bush + Yushchenko = Bushchenko).58 ‘Yushchenko,’ it was claimed, ‘is a project of America, which doesn't need a strong, independent Ukraine’ (see plates 11–13). Posters and adverts appeared, which showed George Bush appearing from behind a Yushchenko mask and saying ‘Yes! Yushchenko is Our President!’, except that the ‘P’ was crossed out to read rezydent, a KGB term for an agent in a foreign country (‘President’ in Ukrainian is spelt ‘Prezydent’). ‘Bushchenko’ also appeared as Uncle Sam, asking ‘Are you Prepared for Civil War?’, and saying ‘Bosnia–Herzegovina, Serbia, Kosovo, Iraq… You're next!’, and as a cowboy riding (a map of) Ukraine.

Much of this Cold War imagery was actually distinctly old-fashioned. Another poster showed a mosquito in the colours of the stars and stripes, sucking Ukraine's blood. The national hero, nineteenth-century poet Taras Shevchenko, was enlisted to say ‘Yankee go home’. A petrol price scare combined two messages: the dangers of invading Iraq and the benefits of links with Russia. It should be pointed out that it was the Yanukovych government, very willing to re-enter the international arena via the ‘coalition of the willing’, which had sent Ukrainian troops to Iraq, where they made up the fourth largest contingent, to curry favour with Washington, whereas Yushchenko at the time promised to bring them home. Yushchenko's wife was constantly subject to the crudest of attacks, and Yushchenko himself was lambasted for leaving his first, ‘proper Ukrainian’ wife, Svitlana Kolesnyk. Finally, a notorious poster showed a Ukraine divided into three different ‘sorts’: with the first class west Ukrainians and the second class central Ukrainians discriminating against the third class in the east and south. Much of this propaganda was distributed indirectly, through the ‘technical candidates’. When an entire warehouse of posters was found by Our Ukraine in October, Roman Kozak and Oleksandr Yakovenko were sent along to claim it was all theirs.59 Kozak, supposedly a Ukrainian nationalist but none too bright, ended up distributing Pavlovskii's Russia Club leaflets on ‘Why Russia Supports Viktor Yanukovych’.60

Much of the black PR depicting Yushchenko or his supporters as ardent nationalists was relayed to the USA, via Yanukovych's adviser Eduard Prutnik and the Odesa-born American citizen Aleksei Kiselev, who helped employ half a dozen American companies on Yanukovych's PR.61 The accusation of anti-Semitism was particularly damaging in America, particularly after an anti-Semitic diatribe, including the claim that there were 400,000 Jews in the SS, was planted in the paper Village News earlier in the campaign,62 which some on the Ukrainian right were stupid enough to defend. The Ukrainian authorities couldn't have it both ways, however, and the global attention given to the domestic ‘Bushchenko’ campaign in October 2004 helped pave the way for their abandonment by Washington during the Orange Revolution.

It should also be stressed that, although the traffic wasn't just one-way, the Yushchenko camp did nothing as bad as this. They focused on Yanukovych's criminal record like a dog with a bone, and exploited it to symbolise the general corruption of the regime as a whole, but both points were fair comment. One advert made in Yanukovych's style, saying, ‘If you are for Yanukovych, go and fight in Chechnia’ could be considered black PR, but the opposition didn't churn out blatant lies on an industrial scale. Instead, Yushchenko constantly talked of dignity, moral values in government and respect for the citizen in a way that Yanukovych could not.

The Poisoning

Neither did the opposition try to kill their opponents. Yushchenko's former chief of staff, Oleh Rybachuk, claims his sources, former agents in both the Russian and Ukrainian secret services, had told him as early as late July 2004 that a plot to kill his boss existed, and that they had warned that poisoning would be the most likely method, although at first it seemed that Yushchenko's minders were more worried that he would succumb to a fatal car crash – another favourite Ukrainian tactic. An early scare came on the evening of 12 August, when Yushchenko was out campaigning in southern Ukraine. As his Audi attempted to pass a KamAZ truck on a road near Kherson, it swerved three times, almost forcing him off the road. His entourage stopped the truck and got the local traffic police to detain the driver, but he was released without charge.63 Even the type of truck was a favourite. The very same model had been involved in the crashes of Viacheslav Chornovil, Valerii Malev, head of the export company embroiled in the ‘Kolchuha scandal’ (the alleged sale of a radar system to Saddam Hussein during the build-up to the invasion of Iraq in 2003), and of Anatolii Yermak in February 2003, a crusading Rada deputy from the ‘Anti-Mafia’ group.

Yushchenko could hardly not travel, however. Back in Kiev, late on 5 September after a normal evening with his aides, Yushchenko set out for what was then supposed to be a secret meeting with the heads of the SBU, Ihor Smeshko and his deputy Volodymyr Satsiuk.64 The meeting, postponed from the previous evening, was arranged by one of Our Ukraine's businessmen, Davyd Zhvaniia, who was the only other person to attend the rendezvous at Satsiuk's dacha in the forests outside Kiev (which was not a cabbage patch, but a villa set in five hectares). Oleh Rybachuk was not present, despite being the normal contact man with the SBU. Neither was Yevhen Chervonenko, who was in charge of Yushchenko's personal security. Chervonenko claimed that he abandoned normal precautions, which included tasting all Yushchenko's food, at the SBU's request, and that Yushchenko initially kept his other colleagues in the dark about the meeting.65 Rumours have circulated about the presence at the meeting of an unnamed ‘fifth man’, supposedly a Georgian, a presumed friend of Zhvaniia (possibly Badri Patarkatsishvili – see page 176).

According to Zhvaniia, although it later became notorious, the September dacha dinner was just one of a series of meetings and other contacts designed ‘to prevent possible “disorder” and forcible methods’, and to persuade the SBU and other organs ‘not to go over the limits, written for them in the Constitution’. The last meeting was in November, after the second round, again at Satsiuk's dacha.66

Yushchenko left his bodyguards at home. According to Satsiuk, the meeting lasted from 10 p.m. until 2:45 a.m. The four men dined on boiled crayfish with beer, a salad of tomatoes, cucumber and sweetcorn, vodka with meats and a final round of cognac – all prepared by Satsiuk's personal chef.67 When Yushchenko got home, his wife says she smelt ‘something metallic’ on his breath. One version of events has it that he vomited on the way home, which may have saved his life, although this remains obscure as the vomiting could be attributed to the drink, which would be difficult to admit to in Ukraine's macho culture.

As he immediately fell very ill, Yushchenko has continued to state that he believes he was poisoned at this time. On the other hand, Yushchenko got what he wanted from the meeting, which, judging by the amount of alcohol consumed, seems to have been cordial enough. During the campaign, one faction in the SBU remained broadly neutral, while another actively helped the Yushchenko team, remaining in secret contact with Rybachuk to pass on the recordings they made of the Zoriany fraudsters. Contrary to later reports that it defected to the opposition en masse, the SBU was obviously split at this time between professionals and recent political appointments by Kuchma and Medvedchuk. Smeshko embodied the split, as he was both. Just to make things more complicated, he had close links to the Russian GRU (the military's ‘Main Intelligence Directorate’), and had served as Ukraine's first military attaché in Washington from 1992 to 1996. Satsiuk was a late political appointment in April 2004, and was widely seen as Kuchma's, or more exactly, Medvedchuk's, man in the SBU. He had previously served as a Rada deputy in Medvedchuk's party, the SDPU(o) and, before that, for the socialists.

The next day, Yushchenko went to see some local Ukrainian doctors, who thought he had food poisoning. On 9 September, after four days of rapidly worsening health, with severe stomach pain and swollen organs, and lesions appearing all over Yushchenko's face and body, Chervonenko spirited him off to a luxury clinic in Austria – just in time to save his life, but, it was thought initially, too late to identify the toxins in his body. Half of his face was paralysed, and a catheter had to be inserted for pain-killing injections. Yushchenko discharged himself after a week, but was forced to return for ten days' more treatment in early October, by which time his advisers began to worry that his whole campaign was unwinding.

A fake statement from the Austrian clinic, the Rudolfinerhaus in Vienna, claiming they had found no evidence of poison, was faxed to Reuters, who assumed it to be genuine and gave it wide publicity, which was, of course, then parroted back in Ukraine. According to one report, the fax was traced to the PR company Euro RSCG, which was linked to Viktor Pinchuk and his favourite foreign spin-doctor, the Machievellian Frenchman, Jacques Séguéla.68 Pinchuk's TV channels, such as ICTV, also exaggerated Yushchenko's past health problems, after the records he had given to the parliamentary commission investigating the affair were leaked, and the claims by the Rudolfinerhaus's Dr Lothar Wicke that he was sacked, and physically threatened, for refusing to support the poisoning diagnosis. More callously, the official media poured scorn on Yushchenko's claims, claiming that his terrible appearance was the result of a bad hangover, a botched botox injection, or even herpes. A later slur claimed a rejuvenation operation using foetus cells had gone badly wrong. Oleksandr Moroz disgraced himself by saying that Yushchenko shouldn't eat so much sushi (sic), but should stick to simple peasant fare, like borshch (a beetroot-based soup, which is much nicer than it sounds), potatoes and lard.69

The government camp also replied with an ‘attack’ on Yanukovych, when ‘several large objects’ were thrown at the prime minister when he was campaigning in west Ukraine on 24 September. Yanukovych was rushed to hospital, but found time to blame the incident on extremist supporters of Yushchenko. However, Poroshenko's Channel 5 captured the event on video, and the ‘several large objects’ were revealed to be one solitary egg. On tape, Yanukovych seemed surprised and initially failed to react, but went on to over-react with a dramatic collapse (see plate 8).70 As often, the attempted replay was a poor copy of the original – on 10 December, Yushchenko's poisoning would be confirmed to have been both frighteningly real and nearly fatal.