The Fraud

The authorities were badly prepared for the first round on 31 October. They thought they were going to win, and that only the minimum amount of fraud would be necessary to achieve that result. Yanukovych had been ahead in the polls for almost a month, after the doubling of the state pension.1 If the poll could have been held sooner, Yanukovych might have come out ahead, but the blatant largesse soon pushed inflation up and the exchange rate down (and would ultimately leave a gap in the budget of UAH8 billion, some 5 per cent of GDP), which scared off other, equally pragmatic voters in east Ukraine, who well remembered the hyper-inflation of the early 1990s.2 The Yanukovych camp had other reasons for confidence, however. The economy in general, at least in terms of headline figures, was doing well. Their man was prime minister. The opposition had little media or money. To their way of thinking, the job had been done.

The Zoriany tapes record the Yanukovych special team's actions and reactions on the day of the first round vote. Panic sets in as it becomes obvious that Yushchenko is clearly in the lead.3

EPISODE ONE, 31 OCTOBER, 00:59: Serhii Larin, a Rada deputy and the leader of Yanukovych and Kliuiev's Party of the Regions, is talking with an unidentified speaker.

UNKNOWN: The turnout's low. It's terrible! Odesa, Mykolaïv, Dnipro [Dnipropetrovsk] and Kharkiv.

LARIN: All right. That will do. Don't say anything on air.

EPISODE TWO, 31 OCTOBER, 16:15.

UNKNOWN: (speaking on Larin's phone) Get everyone ready for action [turnout in Odesa is 48 per cent].

UNKNOWN 2: That's what I'm doing. I understand everything.

UNKNOWN: In Odesa, the turnout must be 80–85 [per cent]. You understand?

UNKNOWN 2: Yes.

UNKNOWN: Do whatever you like.

UNKNOWN 2: I understand.

EPISODE THREE, 31 OCTOBER, 17:07.

UNKNOWN: [Kliuiev?] Why is the turnout so low in Donetsk and Dnipropetrovsk oblasts?

LARIN: We'll take care of that.

UNKNOWN: Do it quick.

LARIN: We're raising the turnout.

UNKNOWN: Do it.

How did they do it? The secret ‘Zoriany’ team were linked by fibre optic cables to the CEC, so that they could intercept and manipulate the results in Yanukovych's favour. Suspicions were aroused by the long time it took for protocols sent by e-mail from local election commissions to arrive at the CEC – and by the fact that they would then all arrive in a rush. What was initially thought to be a ‘transit server’ was in fact simple trespass. Assisted by CEC personnel, the ‘moles’ had access to the CEC's own transit database, where the electronic versions of every local protocol were stored. This intranet remained intact – it wasn't hacked into by some outside server. But as the Zoriany team had access, they could simply alter the results electronically. The data then went to the CEC central server, where it was checked, summarised and placed online at www.cvk.gov.ua. The hackers then destroyed the CEC transit database completely, to prevent identification of their remote access point.4 However, other evidence was discovered on 1 December, when a lorry laden with snow was stopped by chance as it tried to pass unnoticed through the cordon of demonstrators outside the presidential administration. Underneath the snow were piles of documents, some listing election committee members against receipts for payments of $100 a time.5

EPISODE FOUR, 2 NOVEMBER, 10:19: the conspirators express their thanks to Serhii Katkov, their key mole in the CEC (see page 3), as the gap has just changed ‘to our advantage’. Kliuiev is talking with yet another Rada deputy from the Party of Regions, Oleh Tsariov.

SERHII KLIUIEV: I'll tell you what, Oleh, we need to give that bloke [Katkov] some dosh, because if he hadn't reacted in good time and hadn't phoned us…

TSARIOV: I haven't got anything on me.

KLIUIEV: Come and see me at my office, give him a trioshka* and say thank you. If he hadn't given us a bell, we'd be really in the shit.

EPISODE FIVE, 3 NOVEMBER, 22:35: the two bosses of Ukrainian Telecom refer to how the deed was done, and how their tracks must be covered.

LIVOCHKIN: I've just sent you a message. The thing that worries me is that we should ‘sweep up’ there and call it a day.

DZEKON: We've ‘swept up’ everything there … Everything there's closed up. We disconnected everything for the night. Everything's all right.

The Zoriany team, however, were just the last link in the chain. The election fraud had been planned since the spring and most of the other ‘technologies’ also depended on the complicity of the CEC and its equivalent local election commissions. This could be achieved with bribes or intimidation, but the proliferation of covertly financed ‘technical candidates’ was thought by the technologists to be a more reliable method. These might serve other purposes, perhaps as agents provocateurs or as ‘flies’ to nibble at opponents' support, but most were designed solely to exploit the provision in the electoral law for each candidate to nominate ‘trusted persons’ to local election committees. There were twenty-three candidates in the election. As discussed in Chapter 5, four were ‘nationalist projects’ and three were hired guns on the far left. There were also six technical candidates with no other apparent role: Mykola Hrabar, Ihor Dushyn, Vladislav Kryvobokov, Volodymyr Nechyporuk, Mykola Rohozhynskyi and Hryhorii Chernysh. All were so obscure there will be no need to mention them again. All were polling less than 1 per cent, but were able to nominate the same number of ‘their’ supporters (i.e. Yanukovych's supporters) to the committees as the main candidates – that is, between 400 and 450 each. Yanukovych could therefore count on thirteen out of twenty-three ‘trust’ groups, an estimated 60–65 per cent of all members of election committees at all levels, to do his bidding.6 This percentage was increased where necessary by arbitrarily disqualifying opposition representatives at the last minute, or by physically preventing them from doing their work. The election process was therefore corrupted at an early stage.

Come voting day, blatant intimidation was therefore possible at polling stations ‘controlled’ by this method, as were other so-called ‘technologies’, such as padding the turnout with ‘dead souls’ (the impersonation of former voters, voters who were actually alive during previous elections) and ‘cookies’ (extra ballot papers). One ‘technology’ that had been used before was known as the ‘carousel’. The fact that blatant cheating is dubbed ‘technology’ and its various sub-genres given specific names is, of course, highly indicative. Individuals were organised in teams and handed pre-marked (fake) ballots. At every voting station they visited they would ask for a new (genuine) ballot, deposit the fake, and move on. According to one estimate, if each member of the carousel made ten votes each, this would have added half a million votes to Yanukovych's total.7

Another abuse involved voting away from polling stations. The fraudsters were now keen to use any ruse to get ballot boxes where they could be more easily stuffed, or where votes would be cast as ‘advised’, and this was most easily done by the abuse of absentee voting provisions for the old and infirm. Levels of absentee voting in the east and south were massive – and far exceeded any plausible number of real invalids, even given the dire public health crisis throughout Ukraine. In polling station number 76, constituency number 59, in Donetsk, for example, 748 out of 2,248 voters (a whopping 33.2 per cent) supposedly cast their ballots at home, and only five of these were for Yushchenko.8 In four out of six constituencies in Mykolaïv (numbers 129–132, the towns of Mykolaïv and Bashtanka) absentee voting was 30 per cent.9 A total of 1.5 million absentee ballots were cast in all.

Another ‘innovation’ for 2004 was the so-called ‘electoral tourism’ referred to Chapter 1 (see page 6), the mass transport of activists by bus and special trains from one polling station to another for repeat voting. Normally, everyone in Ukraine votes where they are registered. Traditionally, those away from home, on temporary visits, etc., should have a paper to this effect inserted by the interior ministry in their internal passport to show officials when they vote at another polling station. However, in May 2004, the hardline interior minister, Mykola Bilokon, issued a secret directive that this practice would not be necessary at the 2004 elections, opening the door to a variety of frauds that allowed between 1.5 and 2 million fraudulent votes into the system.10 The most notorious involved the special trains provided by the railways minister, Hryhorii Kirpa. When Our Ukraine deputy Mykola Tomenko raised the issue of the trains in the Rada on 19 November, the deputy prosecutor, Volodymyr Dereza, wrote back that: ‘the total number of additional trains put in use inside Ukraine by the Southern, Odesa, Southwestern, Prydniprovska, and Donetsk railways [all sub-regions of southern and eastern Ukraine] over the period of October–November 2004 was 125’. The prosecutor's office also determined that UAH10.6 million (about $2 million) was paid for the use of the trains, which ‘were ordered and paid for by the regional branches of the Party of the Regions and of the SDPU(o), [Russian] Orthodox associations, various enterprises, and some others’. The trains also carried huge amounts of anti-Yushchenko propaganda.11

Some of the voters used in this way were paid, but some were willing to provide their services free of charge, indicating a definite anti-Yushchenko sentiment in the east, but also the peculiarities of local political culture. As the Yanukovych vote was already high in the east, electoral tourism was most important in central Ukraine. Buses and trains from the east went mainly to regions such as Poltava, where two-thirds of the local election commission was under the control of Yanukovych and local authorities could be relied on to cooperate. Significantly, central Ukraine was the region where the Yushchenko vote rose most clearly between rounds two and three – not just because the mood had changed, but because the special trains were no longer running.12 In the three oblasts adjacent to the east, Yushchenko's vote went up from 69 per cent to 79.4 per cent in Sumy, from 47.1 per cent to 63.4 in Kirovohrad, and from 60.9 per cent to 66 per cent in Poltava. His vote also rose sharply in Transcarpathia, from 55 per cent to 67.5 per cent, as the traditional local ‘bosses’ from the SDPU(o) were unable to boss the voters quite so forcefully in the third round.13

Conversely, in areas of strong Yushchenko support, where the local electoral commissions were still ‘controlled’ by the authorities, inaccuracies were deliberately added to voting lists. These might include a wrong address, patronymic or surname. Profuse apologies would be made to the affected voters when they came to the polling station on election day, but they wouldn't be allowed to vote. Within a given constituency this process was carried out randomly, but it was only done in pro-Yushchenko regions, where the assumption was that not too many of the excluded were likely to want to vote for Yanukovych.

In non-controlled stations, the khustynka (‘kerchief’) method was used. Yanukovych people would wear some distinguishing mark, a kerchief or suchlike, to guide their supporters (both their natural supporters and those under various forms of duress) to cast their votes, usually on behalf of the dead souls recorded on a list kept by the man or woman in the kerchief, in their part of the polling booth.

The authorities had much less success with their campaign to drum up votes for Yanukovych amongst Ukrainians in Russia. The Kremlin organised a blatantly pro-Yanukovych congress of Ukrainians in Moscow on 8 October 2004 and talked excitedly of gaining 200,000 extra votes. However, once the Ukrainian courts had tightened up on registration requirements, it was actually easier for Ukrainians living in the West to vote, as they tended to have the right documentation. (2.9 million ethnic Ukrainians live in Russia, having moved in Tsarist or Soviet times. Only Ukrainian citizens could vote, however, and too many of these worked in Russia's black economy.) Only four polling stations were eventually opened in Russia, and a total of 13,000 ballot papers were issued.14 In the second round, 93,496 Ukrainians voted abroad, with Yushchenko having a slight edge (54.7 per cent to 43.4 per cent).

Polling ‘Technology’

According to Volodymyr Paniotto of KIIS, ‘all these operations enabled [the Yanukovych camp] to forge the results of the election [by] up to 10–15 per cent … [across] the whole of Ukraine’.15 Simple fraud needed a cover story, however, which was supplied in this instance by so-called reitingovyi pressing. In October 2004, Yanukovych was temporarily ahead in the polls, supposedly because of sympathy for his unfortunate egg-related accident and, rather more plausibly, because of his belated promises to east Ukrainian voters and the dramatic doubling of the state pension. An innovation that year, however, involved ‘exit poll technology’. As the authorities' scope for possible fraud had been sharply reduced by the independent exit poll released on election night in 2002, this time they conducted rival exit polls of their own.16 It showed just how bad the situation in Ukraine was that no one was prepared to believe the official results; the real struggle was to establish which version of the parallel exit polls people would be more likely to believe. Obviously, however, the fake exit polls were primed to predict Yanukovych's fake victory.

The (real) ‘National Exit Poll’ was a giant NGO initiative, which was collaboratively conducted by the Centre for Social and Political Research (SOCIS), KIIS, Social Monitoring, the Razumkov Centre and Democratic Initiatives, although all conducted their polls separately. KIIS and Razumkov ran ‘anonymous’ polls in which they thought respondents were far more likely to give their true opinion. By this method, KIIS had Yushchenko with a lead over Yanukovych in the first round of 44.8 per cent to 38.1 per cent (later corrected slightly, to 44.6 per cent versus 37.8 per cent), and Razumkov had Yushchenko ahead by 45.1 per cent to 37 per cent. SOCIS had Yushchenko ahead by 42 per cent to 41.1 per cent in an ‘open’ poll, where voters were more likely to feel as intimidated as they did when they were actually voting. Only Social Monitoring had him trailing by 40.1 per cent to 41.2 per cent.

SOCIS president Mykola Churylov caused a sensation by announcing completely different results on TV at 10:30 pm, now claiming that his figures had Yanukovych ahead by 42.7 per cent to 38.3 per cent.17 He never produced any physical evidence for this turnaround, and never explained by what methodology he had arrived at such figures, which gave Yanukovych an even bigger fake lead than anything the CEC would manage to concoct. Churylov had clearly been manipulated by the Yanukovych campaign, and his colleagues would later leave the Sociological Association of Ukraine in disgust. A second ‘Ukrainian Exit Poll’, conducted by the Ukrainian Institute for Social Foundation for Research (a government think tank), the Centre of Political Management, the Institute of Sociology and others, initially had Yushchenko ahead by 42 per cent to 40 per cent, but also reversed it later on, to claim he was behind by 39.3 per cent to Yanukovych's 43 per cent.18 Finally, the agency Public Opinion Foundation (FOM), behind which stood Russian money and Pavlovskii's FEP, failed to release its results. It claimed to have abandoned its poll because of an excessive number (over 40 per cent) of interviewees refusing to state a preference; although it leaked a false report that it had Yushchenko on 39.2 per cent and Yanukovych on 43.5 per cent. It was later suggested by the Ukrainian Marketing Group which had helped carry out the poll that, on the contrary, their research had provisionally placed Yushchenko on 43.5 per cent and Yanukovych on 38 per cent.19 Pavlovskii, in other words, had used very similar figures to those actually obtained, but had switched the candidates' names.20 The parallel count organised by the Yushchenko camp had their man on 40.2 per cent and Yanukovych on 38.9 per cent.21

The count also went badly for the authorities. Administrative resources failed to deliver a fake vote in line with their fake polls. The more votes that were counted, the closer Yushchenko came to first place, even in the official results. According to the chief presidential consultant, Liudmila Hrebeniuk, Yushchenko was ahead all the time.22 Counting was suspended twice as Yushchenko threatened to surge ahead; first on 1 November, with 94.24 per cent of the votes counted, and nearly all the late-reporting areas, mainly in busy Kiev and the rural west, likely to favour Yushchenko.23 During the night, an alleged 50,000 to 150,000 votes from Kiev and Kirovohrad were lost.24 Counting was invalidated (subject to appeal) in three constituencies: 200 and 203 in Cherkasy, and 100 in Kirovohrad, where Yushchenko had led by 25,000. Other, ‘reserve’ ballots were allegedly substituted.

As a result, when counting resumed the next day, 2 November, the gap widened for the first and only time – then began to close again. A second, much longer, suspension was therefore ordered, with Yushchenko about to take the lead. The Zoriany tapes record the background work during the suspension. ‘Valerii's’ surname is unknown, Serhii Kliuiev was a Yanukovych fixer, and Serhii Kivalov was head of the Central Election Commission or CEC – see Chapter 1. The authorities had three types of kompromat on Kivalov, relating to fake degrees handed out when he was head of the Odesa Law Academy, the business dealings of his daughter Tetiana and her company Vivat-Femida!, and some sweetheart land deals.

Progress of the first round count

| Percentage of bulletins counted, 1/11 | 50.27 | 63.36 | 73.48 | 81.42 | 84.32 | 91.76 | 93.85 | 94.24 |

| Yanukovych | 45.48 | 43.28 | 42.78 | 41.82 | 41.43 | 40.39 | 40.14 | 40.12 |

| Yushchenko | 34.25 | 36.26 | 36.64 | 37.53 | 37.92 | 38.90 | 39.14 | 39.15 |

| Percentage of bulletins counted, 2/11 | 94.89 | 95.38 | 96.60 | 97.67 | ||||

| Yanukovych | 40.22 | 40.34 | 40.03 | 39.88 | ||||

| Yushchenko | 39.01 | 38.88 | 39.16 | 39.22 | ||||

| Percentage of bulletins counted, 10/11 | 100 | |||||||

| Yanukovych | 39.26 | |||||||

| Yushchenko | 39.87 | |||||||

Source: www.cvk.gov.ua and the running score kept at www2.pravda.com.ua/archive/2004/October/31/cvk.shtml

EPISODE SIX, 9 NOVEMBER 2004, 17:34.

VALERII: I called and wanted to consult; today is the day of final resolution. Are all actions agreed? Is this true?

KLIUIEV: Yes, what results do you have?

VALERII: Let me see. Yushchenko has a 0.55 per cent advantage right now. But if we can wait a bit longer, tomorrow the courts' decisions will come into force and we will be leading. I tried to reach you, but your assistant took the phone. Later Serhii Vasylovych [Kivalov] has invited us round. I asked Misha to call [Stepan] Havrish [then Yanukovych's representative on the CEC]; Havrish said ‘don't get involved, it's already agreed’. Kivalov also told us that ‘everything is agreed; the councils have been called.’ I know that you also participated in the council, but I also know that I need to receive an order from you directly.

KLIUIEV: That's correct.

VALERII: So here is the plan: we start the conference in a slow manner at six, receive some appeals, speak about methodology and simply stretch time to go into the next day. We need to wait until tomorrow, because tomorrow the Cherkasy court's decisions will come into force.

KLIUIEV: Districts number 200 and number 203.

UNKNOWN: Exactly; this is the exact number of votes we need to lead.

KLIUIEV: Great! Everything is correct. Start the conference today and slowly proceed into tomorrow. Well done. It's good that you called me, thank you.

When the official result was finally announced on 10 November, it was finally admitted that Yushchenko was in front, but it was claimed that he was only leading by 39.9 per cent to 39.3 per cent. The CEC failed to cover some tracks, even on its official website, where in seven regions (Crimea, Donetsk, Dnipropetrovsk, Odesa, Rivne, Cherkasy and Chernihiv) it recorded more votes cast than ballot papers handed out – 129,596 in total.25 The long time taken to fix the result also had a paradoxical side-effect: Yushchenko was now psychologically in front just before the second round.

Oleksandr Moroz was declared third, with 5.8 per cent, and Petro Symonenko fourth, on 5 per cent. The Communist leader Symonenko scored an implausible 3.3 per cent in the traditional red stronghold of Donetsk (less than his national average) and only 5.8 per cent in the neighbouring mining region of Luhansk, compared to a massive 86.7 per cent for Yanukovych (80 per cent in Luhansk) and a miniscule 2.9 per cent for Yushchenko (4.5 per cent in Luhansk). This was highly suspicious. One source claims that: ‘Almost 670,000 [votes] in Donetsk and Luhansk were added to Yanukovych with their [the Communist leaders'] approval.’26 Nationally, Vitrenko won 1.5 per cent, Kinakh 0.9 per cent, and Yakovenko 0.8 per cent. Again, however, the fake candidates that the Yanukovych team wanted to do well nationally, were not allowed to do well in the Donbas. Despite being supposedly the most anti-Yushchenko candidates in the most anti-Yushchenko region, Vitrenko was only recorded at 0.8 per cent in Donetsk and Yakovenko at only 0.6 per cent.

Nationally, all the other candidates scored less than 0.5 per cent and 2 per cent voted against all. The turnout was 74.9 per cent. The minor candidates had helped shift the dramaturgiia in Yanukovych's favour, but they were squeezed by the ‘polarisation scenario’. Their overall vote was too low to provide the cover story that their endorsement of Yanukovych could account for his victory in the second round. Moreover, Yushchenko was able to secure an agreement with Moroz for his support in round two, despite the flirtation of part of his party with the SDPU(o), albeit at the price of agreeing to a package of constitutional reforms (see pages 148–53). Kinakh also backed Yushchenko. Yanukovych was, of course, supported by the faux-leftists Symonenko, Vitrenko and Yakovenko.

The Second Round

The authorities therefore upped the ante for the second round on 21 November. The honest exit pollsters from KIIS were offered first double, then quadruple their previous payment, that is, $100,000, to defect with SOCIS, but declined (this at least showed that Ukraine was not as ruthlessly authoritarian as some post-Soviet states).27 This time, the KIIS–Razumkov poll, with a massive 15,000 interviews, had Yushchenko as the clear winner, with 53.7 per cent to 43.3 (this was later re-weighted to 53 to 44), with 3 per cent against both. Even the tainted ‘People's Choice’ poll undertaken by SOCIS and Social Monitoring had Yushchenko ahead by 49.7 per cent to 46.7 per cent. The authorities were therefore much more reliant than they had been in the first round on the efforts of the Zoriany team, which this time interfered much more blatantly in the counting process. They also fast-forwarded the count, so as to catch potential protesters on the nap. A lead was established early for Yanukovych, which Yushchenko was apparently unable to close. This time there would be no dramatic closing of the gap. With 65.6 per cent of the votes counted, Yanukovych led by 49.5 per cent to 46.9 per cent, and the gap then barely changed. Whereas the count for round one had dragged out for almost two weeks, Yanukovych was now declared the winner overnight, by 49.5 per cent to 46.6 per cent.

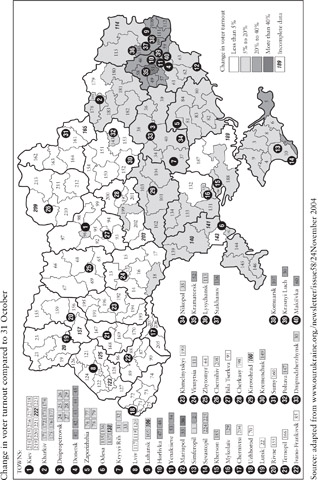

It seemed immediately obvious how the deed was done, however. The opposition had already been informed that the key fraud would take place in the small hours, and be concentrated in east Ukraine.28 National turnout was up by 5 per cent to 80.7 per cent. In east Ukraine the official result was a massive 92 per cent to 6 per cent in favour of Yanukovych. The KIIS–Razumkov exit poll had Yanukovych well ahead, but Yanukovych and Yushchenko were on 84 per cent and 13 per cent, respectively. Falsifying the turnout was more important, however. In Yanukovych's home region of Donetsk, where Yushchenko's supporters were kept off the local election commission, turnout was supposedly 96.7 per cent and the vote in favour of Yanukovych 96.2 per cent to 2 per cent. In three constituencies in Donetsk, Yushchenko's recorded vote was a mere 0.6 per cent. In the Donbas as a whole (Donetsk and Luhansk), Yanukovych's vote went up by almost one million votes between the rounds. He had already won a massive 2.88 million votes in the first round. Now the CEC claimed he had 3.71 million. In other words, Yanukovych's entire margin of victory in the overall national vote was from this implausible increase alone. The map (see page 115) shows how turnout soared in the key eastern regions.29 The utter implausibility of this can be seen from all previous voting behaviour, when the turnout in Donetsk was always below that in west Ukraine and, apart from the second round in 1999, when there was also widespread fraud in the east, also below the national average.

Turnout in Ukrainian elections, 1998–2004

| Turnout (per cent) | Lviv | Donetsk | National Average |

| 1998 | 77 | 63.1 | 69.6 |

| 1999 (first round) | 78.9 | 66.1 | 70.2 |

| 1999 (second round) | 85.7 | 77.5 | 73.8 |

| 2002 | 67.8 | 64.6 | 65.2 |

| 2004 (first round) | 80.8 | 78.1 | 74.9 |

| 2004 (second round) | 83.5 | 96.7 | 80.9 |

Source: www.cvk.gov.ua

The Yanukovych faction countered the opposition's objections to the official figures with the claim that two million votes had been falsified in Yushchenko's favour in west Ukraine. It produced no hard evidence to support this claim, however, except general statistics on emigration, to back up the claim that many west Ukrainians were out of the country at the time of the vote, working in Polish sweat shops, on construction sites in Portugal and as nannies in Italy.30 The accusation also ignores the basic point that Yushchenko's supporters simply did not control the levers of administration in the west and centre of Ukraine. The key powers at election time were the local governors, who since 1994 had been directly appointed by the president (Kuchma), and the Territorial Election Committees (TECs), nearly all of which were controlled by the authorities via the ‘technical candidate’ method. West Ukraine, with little local industry of its own, was also notorious for oligarchs ‘parachuting’ in from further east. Lviv, for example, was largely controlled by the ‘Agrarian Party’ and the SDPU(o), and Viktor Medvedchuk's brother, Serhii, was head of the local tax administration. Many local politicians had joined the Kuchma gravy train. Bohdan Boiko, for instance, was once head of Ternopil council, but ended up as a fake nationalist in the pay of the SDPU(o). Lviv was where the notorious railways boss Hryhorii Kirpa polished his skills, taking over local sanatoria with a series of offers owners were unable to refuse. He moved to Kiev as a reward for helping to fix the local vote for Leonid Kuchma in 1999.

Just to emphasise the point, four governors who failed to deliver the local vote – even in the west the order was at least 10 per cent for Yanukovych31 – were dismissed by the supposedly neutral Kuchma after the first round.

On the Zoriany tapes, the following conversations can be heard.

EPISODE SEVEN, 31 NOVEMBER, 20:07.

SERHII LARIN (another deputy from the Party of Regions and a Yanukovych campaign stalwart): Have a word with Inter [the TV company controlled by the SDPU(o)]. They must announce that there are a lot of violations in western Ukraine. Do you have them under control or what?

UNKNOWN: Yes, all right.

31 NOVEMBER, 20:31.

LARIN: The request is this: [TV must say that] lawlessness is rampant in western Ukraine.

UNKNOWN: We've just said that.

LARIN: It has to be put more strongly in the commentaries – like ‘it's just unprecedented’.

Money was, of course, crucial to the campaign. One much-quoted, if well-rounded, figure stemmed from the comment that: ‘According to opposition sources, Russia … supplied half of the $600 million that Yanukovych is spending on his campaign – including a $200 million payment from the Kremlin-controlled energy giant Gazprom.’32 Gazprom channelled its money through Oil and Gas of Ukraine and the shadow structures coordinated by Prutnik and Kliuiev (see below). The Russian magazine Profil put the figure at $900 million, and claimed Vladislav Surkov, the Kremlin deputy chief of staff, personally approved $50 million.33 Another source claimed $95 million for just the second round.34 Most estimates for the Yushchenko campaign, on the other hand, were closer to $50 million. Significantly, at least two Russian oligarchs who had been impressed by the Yushchenko government in 1999 to 2001, the oil tycoon Mikhail Fridman, head of the Alfa Group (estimated wealth $5.6 billion, actually born in Lviv in 1964) and the Russian Aluminium boss Oleg Deripaska ($3.3 billion), were contemplating an investment on his side, but both were warned off once the Kremlin made up its mind on one-sided intervention in September 2004. Viktor Vekselberg of TNK–BP (estimated wealth $2.5 billion, born in Drohobych, west Ukraine in 1957) was another Russian ‘oligarch’ rumoured to be close to Yushchenko.

Even the Yushchenko camp had to be coy about its expenditure, because official spending limits were so low. According to their final disclosures, the Yushchenko campaign spent only UAH16.8 million ($3.2 million), and the Yanukovych team only UAH14.4 million ($2.7 million) on the 2004 election.35 The unofficial estimates, on the other hand, were simply enormous, even in comparison with American elections, which are costly enough, and get costlier every year. In 2000 George W. Bush spent an official $193 million against Al Gore's $133 million. In 2004, Bush and Kerry between them topped $600 million. It seems astonishing that a Ukrainian campaign could cost anywhere near the same, especially given that the US GDP is 150 times as large as Ukraine's.

The answer is in the disparity of tactics used. The vast majority of campaign spending in America goes on media advertising, especially on TV. Yushchenko's possible $50 million also went mainly on advertising and on maintaining the organisational sinews of a normal campaign. The massive outspend by the Yanukovych side, on the other hand, was typical for the ruling authorities in the former USSR because, not to put too fine a point on it, the money was spent on different things. An entire vote farming industry had to be financed. An army of state officials had to be paid off, from corrupt election officials to hospital managers in Donetsk who closed their half-empty wards and then claimed every bed was occupied by an infirm Yanukovych voter.36 According to an analysis by the Committee of Voters of Ukraine, no fewer than 85,000 officials were involved in election fraud; that is, one third of the entire ‘civil service’.37 In one city alone, Zaporizhzhia in east Ukraine, documents left on the computer of former local administration boss Volodymyr Berezovskyi (no relation to the Russian tycoon Boris Berezovskii) indicated payments of $8.6 million to officials working for Yanukovych. In addition, special teams and political technologists had to be paid for. Technical candidates and their campaigns had to be financed. (Their anti-Yushchenko propaganda was normally ordered by weight.) The state media machine had to be kept working; the reluctant journalists who eventually rebelled had to be paid off. Trains and buses to transport repeat voters did not come cheap. Finally, the complex cross-subsidies that enmeshed ‘official’ businesses in ‘official’ campaigns meant that money could be taken out of campaign funds, as well as put in. Smaller business basically paid tribute, normally by being asked for an advance payment on taxes not due until March 2005 (another reason why the new authorities would face budget problems after the Orange Revolution was over). Bigger businesses would take money out – a certain amount of rake-off was an accepted norm, and the more squeamish needed extra payment in return for their dirty work. And finally, the pensions hike ordered by Yanukovych was so ruinously expensive that some money had to be taken out to pay for that as well.

Most of the spending was channelled through a shadowy company called Donechchyna, although it began to leak funds abroad after the second round. Eduard Prutnik was most often mentioned as the ‘coordinator of financial sources’.38 The most detailed analysis of campaign spending was carried out by the ‘Freedom of Choice’ coalition of domestic NGOs and was posted on their website, www.coalition.org.ua.39 Much of its information was based on inside sources, and its calculations are generally accepted as broadly accurate, and not too out of line with the guesstimates cited above.40

‘Signatures’ refers to the collection of the 500,000 voters' signatures necessary to stand in the election the first place. Unscrupulous or plain lazy candidates would farm this tiresome task out to professional collectors.

‘Mass actions’ are demonstrations, rallies, etc. ‘HQs/Staff’ are the normal human labour needed in any campaign. ‘Regional Press’ involves a high percentage of so-called zakazukha, that is, paid propaganda dressed up as neutral journalism. Payment was normally given for the journalist's agreement to fix his or her name to a pre-written article. ‘Bigboards’ is the local term for billboards in big cities or on highways. ‘Internet’ is self-explanatory. ‘Election control’ means election monitoring, but also the material aspects of fixing the vote. The figures for TV and radio only include direct advertisements. All candidates produced posters and leaflets; the estimates for Yanukovych are that $25 million was spent on his own materials and $10 million on the black PR attacking Yushchenko, including the notorious ‘Bushchenko’ series. ‘Purchase of ECs’, ‘provocations’ and bribes for voters only have expenditure marked in one column.

Campaign spending in the 2004 election, millions of US dollars

| Yushchenko | Yanukovych | Moroz | Symonenko | Parliamentary* | Technical# | |

| Signatures | 0.1 | 2 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 1.2 | 3.5 |

| Mass Actions | 4 | 25 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| HQs/Staff | 21 | 106 | 14 | 14 | 2 | 3 |

| Regional Press | 3.2 | 13.6 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 0.6 | 0.5 |

| Bigboards | 0.1 | 8.4 | 0 | 0 | 1.5 | 0 |

| Internet | 0.8 | 4.5 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.2 |

| Election Control | 3 | 53 | 2 | 1 | ** | ** |

| TV Ads | 4 | 42 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 4 |

| Radio Ads | 4 | 9 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Posters, Leaflets | 5 | 35 | 4 | 4 | 13 | 6 |

| Purchase of Election | 0 | 32 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Commissions (ECs) | ||||||

| Provocations | 0 | 30 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Bribing Electors | 0 | 32 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 46.2 | 392.5 | 26.5 | 24.4 | 18.5 | 17.2 |

* After the first four main candidates, the rest are divided into two groups. The first are those considered ‘parliamentary’ candidates, with some real support: namely, Anatolii Kinakh, Nataliia Vitrenko, Leonid Chernovetskyi, and Kiev mayor Oleksandr Omelchenko.

# All the others are classified as fakes, so-called ‘technical’, candidates. The author would also consider Vitrenko a fake, but she did once have considerable parliamentary support.

** To Yanukovych.

Source: http://coalition.org.ua/index.php?option=content&task=view&id=119&Itemid=

‘Freedom of Choice's’ calculations were for outputs, as it were. Many TV adverts, for example, would have been aired for free on sympathetic channels. So even Yanukovych's massive spending advantage, $392.5 million to $46.2 million, may be an underestimate. The key issue here, of course, is what the Yanukovych campaign did that others didn't do: it had a massive advantage in advertising and in paid stories planted in the regional press, and it had a larger staff. The campaign also spent money on provocations, bribes to voters and election commission officials, and ‘the control and conduct of the elections’. Many of its demonstrations had to be paid for, whereas Yushchenko's supporters turned up for free.

The figures for the ‘technical’ candidates are interesting. Because they were fake candidates, with no pre-established support, getting them the necessary 500,000 signatures from voters was expensive. They also had a strong virtual TV and bigboard presence, but no actual real campaigning costs. Their total spend of $17.2 million can be added to the Yanukovych campaign's $392.5 million.

----

This chapter has set out to demonstrate that the amount of fraud committed on each side was not equal, and that, even at the time, it was not true that ‘we have no way of knowing if he [Yushchenko] was robbed of actual victory’.41 Protesters, who had plenty of hard evidence, never sought to question why a 96 per cent turnout in Donetsk … is proof of electoral fraud. But apparently turnouts of over 80 per cent in areas which support Viktor Yushchenko are not.’42 The authorities, however, had been caught in the act. Would they pay the price?

* trioshka: literally ‘a three’. Slang for some kind of threefold payment, which could refer to $3,000 or similar larger amount, a BMW three series, or even a three-bedroom flat.