The Protest

The mass protests watched around the world after the Ukranian election were obviously pre-planned, but then so was the fraud that led to them. Neither is there anything suspicious about how quickly the opposition reacted. They knew what was coming and they knew they would have to act fast – Yanukovych would come within a whisker of being declared the formal winner within three days of the second round vote on 21 November. According to several sources, both sides expected demonstrations, and assumed that they would probably be bigger than the ‘Ukraine Without Kuchma’ campaign in 2001, but that they would attract no more than 60,000 to 70,000 protesters.1 Pora's leaders hoped to supply 15,000 of their own.2 Tymoshenko caused a storm by saying society was ‘inadequately’ prepared to protest. And it was getting pretty cold, falling from −1°C at the start of the week to −7°C at its end. The authorities expected a tent city, but they had seen those off before. They had no real contingency plans, but they assumed that the deck was sufficiently stacked and the population sufficiently cowed for them to quell a demonstration without trouble.

There had been several practice runs, dating as far back as May – particularly a big rally in July, which attracted 30,000 to 60,000 protesters. Nevertheless, numbers were never high enough really to frighten a regime that, psychologically, at least, always thought in terms of a ‘Romanian scenario’ as its likely end – namely the violent overthrow of the Ceausescus in December 1989 and their summary execution on Christmas Day. It could only think in terms of triumph or implosion. And before 22 November, the opposition weren't exactly massing at the gates. Even after Zinchenko took over from Bezsmertnyi, the Yushchenko team was being criticised for its passive approach, as a result of which most of the rabble-rousing had been left to Tymoshenko.3 An estimated 70,000 welcomed Yushchenko home from Austria on 18 September, despite the fact that his absence had only been explained the day before. On 16 October, some 40,000 students from all over Ukraine turned up for a pro-Yushchenko rally in Kiev, during which they passed a mock ‘no-confidence vote’ in Yanukovych's cabinet. The next Saturday, 23 October, rather more, an estimated 50,000 at least, attended the ‘Force of the People against Lies and Falsification’ rally that ended up outside the headquarters of the CEC. The provocation with the militia (see page 82) was the kind of thing that happened all the time before the foreign media unexpectedly arrived in Kiev en masse in the middle of the Orange Revolution. Not surprisingly, therefore, many people expected more of the same after the decisive vote on 21 November.

The Maidan

The Yushchenko team weren't secretly preparing for revolution. They were prepared to protest, but rather too many were expecting defeat for their plans to be wholehearted. Yushchenko could have called for protests after the first round, but he held his fire until the second (though Pora had set up a small protest camp downtown – outside the main university, UKMA, on 6 November). Quite sensibly, he knew he had to let matters take their course. Slightly more cynically, his team knew it was the steal itself – which everybody knew the authorities were planning – that would provoke protests. Yushchenko's initial call was for a limited number of protestors to assemble in Kiev's Independence Square, popularly known as the ‘Maidan’, when the polls closed at 8 p.m. on Sunday 21 November. The rationale at this stage was to gather for the announcement of the exit polls and to undertake a parallel count in public – and it was then assumed that the official count would take several days, if not the nineteen days taken after the first round. On the other hand, Bezsmertnyi had applied with sufficient notice for a ‘concert’ to be held in the square from 21 November, providing good cover for several options. The stage in the Maidan was therefore built on the Sunday – early, but for a specific purpose. The first tents – not yet actually protest tents – were also set up on the Sunday. There were twenty-five tents for each of Ukraine's twenty-five oblasts. With or without further scaled planning, the crowd that Sunday night comprised between 25,000 and 30,000 people. Some have called this ‘premature protest’ on Yushchenko's part, the first step in a coup d'état, and have accused his side of never intending to accept the official results, whatever they were. But at the time, this was a carefully calibrated move. In any case, as everyone expected a massive fraud, it would be surprising to expect the opposition simply to sit back and take it. (The Georgian protest was more controversial, as it used a partial parallel vote to discredit the official results before they were announced.) After the Sunday night gathering, most people went home (see below). The situation was hardly revolutionary at this point.

The real surprise came on the morning of Monday 22 November. Yanukovych was pre-announced as the winner, but the Democratic Initiatives centre was printing leaflets in batches of 100,000, using the KIIS–Razumkov exit poll data to declare, ‘Viktor Yushchenko Has Won! By 54 per cent to 43’. According to Zinchenko's deputy, Mykola Martynenko, ‘we did not prepare for revolution … we asked people to defend their choice. We knew people would come, but did not know that it would be so many’ (the word Martynenko used for ‘defend’, vidstoiuvaty, implies ‘to stand for a long time’).4 Armed with the leaflets, an estimated 200,000 to 300,000 Kievites skipped work to crowd the Maidan and the adjoining main street, Khreshchatyk, by mid-morning. This was the moment when ‘revolution’ became an appropriate word, in that everybody's expectations were now confounded. The authorities had miscalculated; the masses surprised everyone with their entrance stage-left, the opposition's pessimism was abruptly challenged, and the world began to sit up and take notice. Sheer numbers already made the initial difference. Suddenly, there was a televisual event. Martynenko claimed that he had talked privately with the Kiev mayor Oleksandr Omelchenko on the Sunday evening, and that he had said: ‘If you bring out 100,000 I'm with you, we'll take power in one day! If it'll be 99,000 I won't be with you’.5 After the Revolution he joined the bandwagon soon enough, but not soon enough for some. Other reports have it that the army had admitted in private that it would defer to anything more than 50,000.

Over the next three days, numbers would be augmented by those arriving by bus and train from west Ukraine, but contrary to the later myth of their disproportionate numbers, west Ukrainians, facing either an overnight train journey or dodgy roads, were simply unable to arrive as spontaneously or as quickly as was claimed. Obviously, however, once they arrived they tended to stay longer, for practical reasons (by the end of the week, there were an estimated 50,000 from the west). Yanukovych's Donetsk team had numbers on their side in east Ukraine, but the epicentre of government, of electoral fraud, and the world media's likely point of interest was the capital, and Kiev city had voted heavily for Yushchenko in the second round (74.7 per cent, even on the official figures). Kiev businesses, small, medium and large, had grown impressively during the economic recovery since 2000, and had begun to resent the influence of the arriviste Donetsk elite since Yanukovych had become prime minister, muscling in on real estate and hotel deals, and on Kiev's huge new shopping mall ventures. A drunken cavalcade of Mercedes down Khreshchatyk to celebrate Yanukovych's appointment back in 2002, with horns honking amid shouts of, ‘We are the masters now’, had not been a good start.

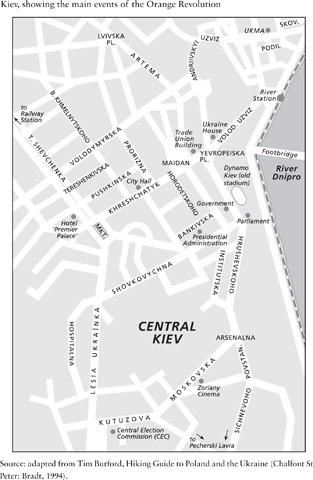

By Tuesday 23 November, the protest was properly organised, and the Maidan became the centre of events. It also became a proper name, a shorthand, sometimes even an anthropomorphised agent. The ‘people’ became the ‘Maidan’, and individual people began speaking in its name. Maidan is the Ukrainian word for ‘square’, a borrowing from Turkish. It was rarely used before 1991 – the Russian word is ploshchad – and took some time to catch on thereafter. As a space, however, the Maidan is symbolic of the new Ukraine. In Soviet times, it was a pedestrian and public transport thoroughfare, its underpasses notoriously grotty, the stench of stale urine fortunately masked by dense tobacco smoke. In the late 1990s, these were cleaned up, and a huge underground mall was built beneath. An eclectic mix of kitsch statuary appeared above ground. During the Orange Revolution, the sheer number of people who congregated in the area meant that the metro missed out the Maidan stop, but the mall underneath stayed open. The local McDonalds, at least, sold cheap coffee for the duration. Viewers around the world only saw the crowds above ground, of course.

Yushchenko's campaign team proved better at organising a protest than organising a campaign. Roman Bezsmertnyi came back into his own as the Maidan's main ‘commandant’, and Our Ukraine businessman Davyd Zhvaniia was the main practical provider of tents, mattresses, food, transport and bio-toilets.6 He had, indeed, ensured a supply of tents before the event, which Yanukovych supporters latched on to as evidence of a plot, but in the end, there weren't nearly enough to go around. The rest came mainly from donations once the protest got going, and some from the city administration.7 Yurii Lutsenko, the young Socialist who had been one of the main leaders of the Ukraine Without Kuchma protests in 2001, was the Maidan's political ‘DJ’. Soon enough, its other DJs had massive speakers and a plasma TV screen behind them. According to Yushchenko's aide, Oleksandr Tretiakov, speaking in December, the total cost of the Maidan was UAH20 million (about $3.8 million) plus $1 million in US money, nearly all of which was made up from small donations and not a penny of which came from abroad.8 Thousands of acts of individual kindness kept the protesters going – and were extended to Yanukovych supporters, as well. The food and shelter provided by so many individuals could not be costed. Meanwhile, two firefly websites, www.orange-revolution.org and www.2advantage.net, suggested donating money to Privatbank, part of the Dnipropetrovsk ‘clan’, instead. Some money, however, allegedly came from the Ukrainian-born Russian citizen Konstantin Grigorishin and from Aleksandr Abramov, whose Evrazholding group had sought to bid for Kryvorizhstal with another Russian company, Severstal.9

Contrary to the authorities' expectations, the numbers on the streets continued to expand. In the first three days, this was the opposition's key card; no one in authority was yet defecting to support them, despite some west Ukrainian councils voting to recognise Yushchenko as president. There was a certain falling off of the crowd at night, but not by enough to improve the authorities' physical opportunities for clearing the streets. Numbers became so large that counting was unreliable, but the organisers estimated a maximum number of half a million by the first Saturday, 27 November.10 Yevhen Marchuk, who still had good contacts and intelligence networks, claimed there were over a million.11 According to a poll undertaken by KIIS in mid-December, 18.4 per cent of the adult population claimed to have taken part in the protests throughout Ukraine, but this rose considerably in west (35.5 per cent) and west-central Ukraine (30.1 per cent). In Kiev, that would work out at about 800,000 people. More than half (57 per cent) of those taking part in the meetings came from large cities (defined as having a population of more than 100,000). Interestingly, despite the pictures of photogenic young people on the Maidan only 27.5 per cent came from the youngest age group of 18–29 year olds (only slightly more than this group's 22.4 per cent share of the population as a whole) and 23.7 per cent came from the 30–39 age group.12

The crowds now occupied much more than the Maidan, spilling over on to most of Khreshchatyk and the adjoining streets. More people did not just mean that more bodies were present. It meant that the social profile of protest got broader and broader – the sons and daughters, even the grandparents, of the militia were now on the streets. The growing numbers also allowed the leaders of the protest to broaden their tactics. The Yushchenko team deliberately sought to disconcert the authorities by planning a surprise a day – as with Tymoshenko's ‘theatre of opposition’ in 2002. On Tuesday 23 November, Yushchenko's symbolic, but technically meaningless, decision to read out the inauguration oath in parliament took the moral high ground. The international response, particularly Colin Powell's condemnation of the fraud on Wednesday, was more vigorous than expected, especially as the authorities had concentrated on the more ambiguous messages that had previously come from the likes of Donald Rumsfeld. The foreign response was fuelled by the emergence of transcripts of Yanukovych's team, who had been taped in the act of organising the fraud on election day. After a low point on the Wednesday, Thursday 25 November was a key day of transition, with the protestors fanning out to encircle public buildings close to the Maidan.

The opposition used a three-fold division of labour to keep the authorities off guard. Yushchenko mainly took the constitutional high ground, carefully bridging the gap between those who simply demanded that the fraud be recognised and those who demanded he be installed as president. Even after he took the inauguration oath on Tuesday 23 November, Yushchenko was mindful that the enormous numbers on the Maidan meant that his own supporters had been joined by hundreds of thousands of other voters who were more concerned with the threat to democracy in general. Tymoshenko acted as rabble-rouser, returning to a role that could have been tailor-made for her after a sometimes difficult campaign season, and Pora were more radical still. Tymoshenko often seemed rash, calling on the crowds to seize power by taking over airports and railway stations. She also set deadlines, which, when issued to the Supreme Court over impending legal decisions were particularly inappropriate. On Sunday 28 November, she felt confident enough to threaten Kuchma's physical safety. She peppered her speeches with wild talk of there being Russian special forces everywhere in Kiev, and of a rumoured ‘insurrection’, which she claimed had been sponsored by Medvedchuk. In December, Hryhorii Omelchenko, a deputy from the Tymoshenko bloc, claimed that weapons from the Black Sea Fleet had been transferred to Donetsk, to arm gangs who would descend on Kiev.13 In private, Tymoshenko rowed with Bezsmertnyi, who accused her of making repression more likely.

But Tymoshenko's job was to maintain the regime's fear of insurrection. The division of labour held. Pora, meanwhile, were given their tent space, but were kept off the stage, and reserved for the potential dirty work. Both the Maidan and Pora obeyed clear rules: no alcohol; stay clear of the police; be on your guard against provocateurs; and, above all, ‘do not allow a single violent act’. It was not exactly sex and drugs and rock and roll, but for some, it was two out of the three, and even two engagements were announced on the Maidan.14 Instructions were even given on how to greet demonstrators from the other side (warmly). One of the most telegenic images of the whole Orange Revolution was of Tymoshenko placing a flower in a militia man's shield (see plate 19), deliberately recycling an iconic gesture from the 1960s. Another was when militia were seen tapping their feet to the music of one of the folk groups who were entertaining the crowd. The closest anybody came to breaking the rules was an attempted break-in at the Rada on Tuesday 30 November. However, Yushchenko and his team pushed the intruders back from the inside.

In private, during nightly debates, there were many who were calling for more direct action – namely to storm, rather than just encircle, the key government buildings. Significantly, this idea did not really originate with Pora, who had chosen a method to stick to, but with Tymoshenko and the more radical members of Yushchenko's camp.15 There were a few sticky moments when the protests seemed to be losing momentum, but Yushchenko's restraint would, in retrospect, seem wise.

Although Pora were not on the stage in the Maidan, their tactics caught hold. Humour was everywhere and ‘daily jokes’ were circulated. These don't always translate well, but here goes: ‘We have started to live for the better’, says the government; ‘We are glad for you’, reply the people. People latched on to the more gullible parts of the Western media, who were echoing stories of an American ‘plot’, and embroidered their jackets with ‘Made in the USA’. Placards showed Putin waving an orange flag. Most popular were the ‘Yanukdoty’, which mocked Yanukovych (jokes are anekdoty in Ukrainian), especially the mock-ups of his own agit-prop (see plate 4). The Maidan also developed its own language, especially the chants and slogans, which included ‘We are together’ and ‘Together we are many. We will not be defeated!’ (Razom nas bahato. Nas ne podolaty!) These made obvious sense, but also harked back to the lessons of 2001. ‘The World is With Us’ was a powerful reminder of the international media presence, that did much to restrain the authorities. In Russian, this also means ‘Peace is With Us’. After the Revolution, the slogan would be coopted by phone advertisers, as Mir Vam (‘The World to You’). Significantly, although the crowd would chant for Yushchenko and Tymoshenko long and hard, few of the slogans really moved from the general-political to the personal. One exception, the poster and T-shirt that depicted Yush-che-nko in the style of the classic Che Guevara poster of the 1960s, seemed almost gently to mock his moderation.

The three strands of the opposition were therefore weaving together well. The CEC's declaration that Yanukovych was the victor on Wednesday 24 November upped the ante, and the next day the demonstrators took over Trade Union House on the north side of the Maidan, the Ukraine House (formerly Lenin House) to the left, on Khreshchatyk, and the city hall to the right. This ensured both practical support for the protesters and somewhere to house the flood of small donations of food and clothing. Pora now came into its own. Its role was to block government buildings, the presidential administration, and even Kuchma's dacha outside Kiev at Koncha-Zaspa. More exactly, Pora provided ‘a couple of thousand [people], no more; their job was to create an initial “nucleus” for the demonstrations; although further into the revolution Pora symbols were very popular, so many non-members would carry a sign or a yellow (or even black) bandana’.16

In the first week it was pressure on the streets that counted. By Friday 25 November, the authorities were beginning to lose both unity and nerve. One more nervous member of the CEC withdrew his signature approving the results, making him the sixth honest member of the CEC to rebel. If another two followed, the whole election would be legally invalid. The Supreme Court bought the opposition precious time by agreeing to review Yushchenko's appeal against the results on the Monday, and so making official recognition of Yanukovych impossible. International mediators also arrived on Friday, when Yushchenko dramatically switched tactics by calling for a new vote in December. Yanukovych countered with an offer to allow a new election in the two Donbas oblasts only. He also disingenuously suggested that as president he might make Yushchenko prime minister. Neither offer was remotely attractive. But the opposition was now back indoors.

The Media

The revolution, of course, was televised, although the authorities controlled all the more popular Ukrainian channels. The main state TV channel, UT-1, reaches 98 per cent of Ukraine, but is less popular in the east, where the largest channels, 1 + 1 (market share one third) and Inter, which has the exclusive right to broadcast material from the Russian First Channel, are private. All three, UT-1 rather more opaquely, were controlled by the shadowy structures of the SDPU(o), and therefore ultimately, though holdings were not in his name, by the head of the presidential administration, Viktor Medvedchuk. Inter and 1 + 1 were vehemently anti-Yushchenko. Three other channels were controlled by the rival Pinchuk group based in Dnipropetrovsk, and were pro-Yanukovych, although somewhat less strident. Of these, ICTV is more popular in central Ukraine, STB is an entertainment channel, full of reality TV and the national striptease championship, and New Channel shows mainly films and family shows. A new channel backed by Akhmetov, called simply ‘Ukraine’, was launched in Donetsk in January 2004. The only two opposition channels were also recent set-ups; these were Poroshenko's Channel 5, although that only reached 48 per cent of Ukrainian territory, and Era, which was run by Andrii Derkach, who had previously been close to Pinchuk, but was now putting out feelers to the opposition. Era, however, only broadcast via UT-1 early in the morning and late at night, after 11 pm.

There was some discontent among channel staff before the election. Seven journalists resigned from 1 + 1 on 28 October in protest at their editors' particularly blatant bias. However, a more serious rebellion began on 22 November, when the chief editor had to read the news himself. Inter and 1 + 1 had only one reporter covering the Maidan, until he resigned on 25 November. The joke circulated that 1 + 1 stood for Viacheslav ‘Pikhovshek [the station's notoriously biased anchor] + a cameraman’. On Wednesday 24 November, UT-1 news was busy celebrating Yanukovych's victory, but the signing translator, Nataliia Dmitruk, indicated: ‘The Central Electoral Committee falsified the results of the election. Do not believe what you are told. Our President-elect is Yushchenko. I am very sorry that I had to translate lies before. I won't do it any more. I am not sure if you will ever see me again.’ Viewers never did see her on the screen again, as she was promptly sacked, but she did appear on the Maidan instead. On 25 November, 1 + 1 started up coverage again, but promised to be objective.17 By the weekend, therefore, the mass audience in Ukraine was beginning to see the same pictures of the Maidan as the growing international audience. In east Ukraine, however, coverage was still heavily biased – and it should be pointed out that Channel 5, despite a huge surge in its ratings, was often guilty of cheerleading.

The accusation that the media ‘created’ the revolution, as it supposedly had done in Georgia with the manipulation of the channel Rustavi-2, hardly stands up to scrutiny. More or less the opposite is true. Georgia had one main channel, but in Ukraine the pro-Yanukovych channels (and papers) remained dominant, though they were haemorrhaging viewers because of their failure to cover events objectively, or even cover them at all. However, there were some elements of clever manipulation. One thing the organisers of the Maidan got spectacularly right was their understanding of the power of TV images to form public opinion in the West, and, to an extent, at home. The Yushchenko team hired a satellite station so that any TV company in the world could easily obtain pictures of the peaceful but determined crowds. This ensured that the Maidan would always be the main story, the implied epicentre of events.

Another equally important media battle was won by the opposition at an earlier stage. The Yanukovych media effort was coordinated by the likes of Pavlovskii and took the typical post-Soviet approach, using the commanding heights of the mainstream media to launch blanket propaganda. Dirty tricks were produced on a Fordist industrial scale, with millions of copies of fake leaflets and posters mocking ‘Bushchenko’. The opposition, however, won the battle of the internet and other alternative media hands down. It was not that Pavlovskii, Gelman et al. didn't use the internet. They set up a series of characteristic sites either for obvious black PR purposes (www.provokator.com.ua, and www.aznews.narod.ru, based in Russia) or for black PR masquerading as news (www.temnik.com.ua, www.proua.com, www.for-ua.com). The rival opposition network, however, won the battle for hearts and minds, including most ‘opinion-formers’ in Kiev. Opposition sites were groovier, funnier, more informative, and, in the last analysis, simply more honest. The new NGO sites (see pages 75–6) now interacted with the ‘traditional’ opposition web (www.pravda.com.ua, www.obozrevatel.com, www.obkom.net.ua, www.glavred.info), and with new satirical or blog set-ups. Internet access rose by 39.6 per cent throughout November, and continued to rocket up thereafter. Vladislav Kaskiv of Pora claimed this aspect of their work was more important than their physical contribution to blocking buildings and helping with the demonstration. He claimed that www.pora.org.ua had become Ukraine's fifth most popular site, and that the organisation had distributed a massive 70 million copies of printed materials.18

The opposition was also much more skilled than the old regime in posting video clips, often from camera phones, on the net – Channel 5's comic masterpiece of the Yanukovych ‘egging’ incident, for instance, received 90,000 hits in a week. Topical internet games were also hugely popular. These included Khams'ke yaiechko (a play on words, meaning ‘ham and eggs’, but also the ‘thug's bollocks’), in which players fought a war of control over the regions of Ukraine by bombarding Yanukovych with eggs; and Dmytro Chekalin's Veseli yaitsia (‘Merry Eggs’).19 The latter, along with the cartoon series ‘Operation ProFFesor’ (like many post-Soviet politicians, Yanukovych had arranged a doctorate in economics for himself, but, like Dan Quayle, famously misspelled his qualification in public), which placed Yanukovych in various satirical roles from well-known Soviet films, were both allegedly privately backed by none other than Tymoshenko.20 There was also a web site, www.ham.com.ua, devoted to jokes about and attacks on Yanukovych, the ‘big kham’ (in Ukrainian, pronounced with a faint ‘k’). The other side's attempted response, ‘Lampa’ (http://lampa.for-ua.com) was pretty lame in comparison. The opposition also texted campaign slogans to mobiles, and used them to give times and places for demonstrations. Mobiles are as popular in Ukraine as they are in the West, albeit for different reasons (the local phone network is rubbish, and it's the only way to contact people who don't have secretarial staff), but the Yanukovych camp didn't even try to target the opposition. In this sense, given technology leapfrogging, the Yushchenko campaign was as modern, even more modern or more post-modern, than any in the West.

This was one reason for the one-way traffic in cultural icons appearing at the Maidan. Eurovision winner Ruslana, for instance, was an important early performer, who also went on hunger strike and set her next video amongst the photogenic crowds (having defected from her original role as a ‘cultural adviser’ to Yanukovych). The Klichko brothers, Ukraine's world-champion boxers, said the right thing to the crowd about their force being with the demonstrators (they had also promised to ‘train’ Yushchenko for the TV debates). Torch singer Oksana Bilozir sang repeatedly, her reward was to become Ukraine's youngest-ever minister of culture in the New Year. The girl group VIA Gra remained bravely scantily-clad. Old favourites, such as the 1970s refugee Taras Petrynenko, performed almost every day, and were soon joined by the giants of Ukrainian rock, V-V (Vopli Vidopliasova, or ‘Vidopliasov's Screams’, a reference to how a Dostoevsky character signs his letters) and Okean elzy (‘Elza's Ocean’). There was also plenty of folk music, from the likes of Kobza, for the middle-aged. The revolution's theme song, Razom nas bahato, was a rap, but was home-made and released on MP3.21 Quite sensibly, the Maidan's organisers hoped to encourage as many different groups of the population as they could to stay in the square for as long as possible. Despite the cold, the Maidan remained exciting. The festival atmosphere was a wonderful way of maintaining morale, and of keeping a photogenic feed going to the world's media. Many protestors stayed there permanently, confounding the élite's disdain, and would have kept going longer if that had been necessary. Many kept coming back again and again. Some were sorry when it was all over.

The Potential Crackdown

Not everyone was so jolly. From the very beginning, Yanukovych and Medvedchuk were pressing for Kuchma to take direct action, but most of the elite remained risk-averse. On Sunday 21 November, Yushchenko actually told the first crowds to go home for the night. This presented the authorities with an ideal opportunity to seize the Maidan, but they failed to do so. On the next night, Monday 22 November, with almost a hundred thousand people still in the Maidan, the lights were turned off, but again nothing happened. The next day, Tuesday 23 November, however, 30,000 would-be counter-demonstrators were brought by train from the Donbas and stationed outside Kiev, at Irpin. As this was reported on Channel 5, the element of surprise was presumably lost. Channel 5 also claimed many had arrived drunk. So they were stood down and sent back. Another version has it that demonstrators from the east, possibly extra demonstrators, were turned back halfway, at Kharkiv. If Kuchma had countermanded the order, then the regime was already losing its nerve, though there remained much nervous talk of another ‘Romanian scenario’. The reference this time was to a notorious two-day rampage in June 1990 by Romanian miners from the Jiu valley, who were brought to Bucharest by President Iliescu to attack his opponents. As a result of the clashes, twenty-one were left dead. The Ukrainian equivalent might have involved either similar bloodshed, or a staged confrontation, providing an excuse to ‘restore order’.

As early as Wednesday, when the world's media arrived in force, option one – a ‘blitz’ declaration of Yanukovych as the victor and the use of agents provocateurs as an easy excuse to disperse limited crowds (the formula that had allowed the authorities to survive the Gongadze scandal back in 2001) – was already unavailable. This was fortunate, as some in the Western press were already primed to concentrate on the ‘nationalist threat’ from the likes of the UNA.22 Yushchenko was criticised by some for taking the presidential oath in the Rada on Tuesday 23 November, but his boldness had clearly unnerved the authorities. The CEC went ahead and announced Yanukovych as the winner on Wednesday, but one peculiar feature of Ukrainian law is that election results are not official until they are actually published in official papers such as Uriadovyi kurier (‘Government Courier’) – election time is probably the only time anyone would actually read such a notoriously boring paper. The Supreme Court forbade official newspapers from publishing the results, but deputy premier and old Kuchma stalwart Dmytro Tabachnyk ordered them to be published anyway, resulting in some overnight drama as opposition deputies rushed to the Courier's offices to prevent the printing going ahead. The ‘Romanian scenario’ seemed most likely on Wednesday 24 November, when thousands of miners marched into Kiev along Lesia Ukraïnka Boulevard. However, their destination this time was no further than the CEC, where they celebrated Kivalov's announcement of Yanukovych's victory, had a barbecue and went back to their base outside Kiev.

The authorities assumed that the worsening weather would sharply reduce the number of protesters, as it had done in 2001. It was an indication of the semi-authoritarian nature of the Kuchma regime that its first instinct was not to crack heads, but to consult the weather forecast. Throughout the first week of the crisis, the authorities were also constantly let down by their inability to put their supporters on the streets in competitive numbers, largely because of their natural inclination to pay or to coerce virtual support, rather than to motivate those who genuinely believed they were right. That is, the fault was theirs. It wasn't, as some reports chose to imply, that Yanukovych's supporters were somehow inherently lazy, drunken or doddery. Busloads of easterners were pre-paid to come to Kiev, but they simply melted away on arrival. The authorities also suffered from doing things on the cheap. Many Yanukovych supporters were sent to Kiev with only a one-way ticket, or with their internal passport held at home to ensure ‘good behaviour’ – which made it difficult to buy a return ticket, and left many stranded in Kiev. (Lviv council, in the west, was also accused of using its official budget to help fund travelling protesters to get to Kiev.) The pro-Yanukovych demonstration in Kiev, held on Friday 26 November, embodied all of these weaknesses at once: it was small, it was held near the railway station, a good two miles from the Maidan, and it only lasted two days. During the roundtable discussions, Yushchenko disdainfully said to Yanukovych, when he disingenuously proposed both sides should take their protesters off the streets, ‘You can tell your five thousand people to leave.’23 Although they were often sneered at, it should be pointed out that the easterners' passive and peaceful behaviour was as creditworthy as the restraint shown on the Maidan. Yanukovych had tapped real issues of concern in east Ukraine, but his supporters sensed that something was not right and that they were being used. Both sides showed great maturity in not being manoeuvred into the conflict that some ‘technologists’ so desperately wanted. It takes two sides to avoid an argument.

By now, there were so many people on the Maidan that any crackdown would have been extremely bloody. As early as Monday 22 November, cars and buses had been positioned in side streets leading to the Maidan to make any assault more difficult. Some expensive-looking Mercedes were parked amongst them, though it was not clear whether this was done with the owners' permission. Two former SBU generals, Oleksandr Skipalskyi, and Oleksandr Skibinetskyi, addressed the Maidan on 25 November, promising they would not be a party to any spilling of blood. A unit of young interior ministry cadets defected on 26 November, providing great TV when they marched into the square decked in the opposition's chosen colour of orange. The gain was initially more psychological than real, but more broadly it was clear that any use of forces would meet resistance at several levels. Yushchenko's ‘security chief’, Yevhen Chervonenko, later claimed that he and Zhvaniia were prepared to organise a forceful response to any provocation.24 Zhvaniia has rather more explicitly stated that this meant arms or armed units, though these were sensibly kept away from the Maidan, despite rumours of snipers being placed on the roofs. There seems to be an element of myth-making here, as more or less the opposite was claimed at the time, with Yushchenko's people constantly stressing their peaceful intent. It is well-established, however, that SBU men were in the square to monitor and liaise, but also potentially to act in its defence.

Yanukovych was certainly blowing his top in private and, according to one first-hand report of private phone calls, Putin was also applying pressure. When Kuchma rang him after the second round for advice, he started by claiming, ‘Everything's normal, the elections have been won, but there's a few problems – the opposition is getting agitated, there are demonstrations, tents. So I want to discuss what to do.’ To this Putin replied, ‘It's up to the president of Ukraine, not the president of Russia. But in general, in theory, in such circumstances, presidents introduce a state of emergency, or there is a second variant – you have an elected president [Yanukovych], you could transfer power.’ And at that moment, Kuchma made a fantastic statement – ‘Well, how on earth can I hand over power to him, Vladimir Vladimirovich? He's just a Donetsk bandit.’25 This last statement is indeed extraordinary. Some have taken it as evidence that Kuchma never really wanted Yanukovych to win. In the context, it seems more like evidence of the splits and uncertainty in the regime, as they wondered how to respond to the new situation they now found themselves in.

Accordingly, when Yanukovych raised his demands on Saturday 27 November at a key meeting of the National Security and Defence Council held away from the turmoil, just outside Kiev at Koncha Zaspa, he got short shrift from the SBU chief, Ihor Smeshko and from Kuchma too. Reportedly, Kuchma slapped him down by saying, ‘You have become very brave, Viktor Fedorovych, to speak to me in this manner … It would be best for you to show this bravery on Independence Square’, i.e. the Maidan.26 Presumably, this was a reproof, rather than an invitation. Kuchma, by most accounts, wasn't temperamentally prepared for violence. His metier was divide-and-rule, not force, and he seems seriously to have believed he would be rehabilitated after the Gongadze affair in prestigious retirement. He had prepared a charitable foundation as a comfortable sinecure, and ‘written’ several books. The most famous of these, Ukraine is not Russia, attracted a review from Mykola Tomenko, who commented with acid sarcasm that ‘the presence of Leonid Kuchma could sometimes be felt in this authors' collective’ of anonymous historians, at least in the bits that were ‘insignificant and more or less autobiographical’.27

There were several reports, however, that violent measures were seriously contemplated on the night of Sunday 28 to Monday 29 November. Shortly after 10 p.m., some 10,000 to 13,000 troops under the deputy interior minister Serhii Popkov (the head of internal forces) were supposedly mobilised and supplied with live ammunition and tear gas, and allegedly began moving towards Kiev from all points: from Petrivka (the north), Boryspil (the airport in the east) and Zhytomyr (the west). The troops were reportedly from Crimea and had been kept isolated and ignorant of events. The use of outsiders, who might be more prepared to crack heads than local troops, was a key principle from the hardliners' handbook; the tactic had been used with deadly effect in Tiananmen Square in 1989, but forgotten in Moscow in August 1991. The plans were supposedly derailed by a flurry of phone calls: from SBU chief Ihor Smeshko to key Yushchenko campaign aides Oleh Rybachuk; from Smeshko and Vitalii Romanchenko, head of military counter-intelligence, back to Popkov; from Smeshko to interior minister Mykola Bilokon; from Rybachuk to the American ambassador John Herbst, who phoned Pinchuk, who contacted Medvedchuk; and from Colin Powell to Kuchma, although this last call was declined.28 The regular army contacted the interior ministry, to say they were unwilling to do the regime's dirty work. According to Borys Tarasiuk, ‘by two o'clock we had the situation under control’.29 One version has it that Kuchma himself gave the ultimate order to stand down (it was unlikely that Smeshko could have done so on his own), because Yanukovych had acted unilaterally in attempting to mobilise the troops. Another is that Medvedchuk gave the order to use force, and tried to make it look as presidential as possible. Popkov would have wanted to see something on paper and, given the chain of command, either man would have gone via Bilokon to start the operation. At the time, Tymoshenko blamed Bilokon. Popkov was reportedly promoted, presumably for having agreed to do nothing at the time of the revolution, but, unsurprisingly, was removed in the New Year.

Others consider that the key story on which much of this speculation is based, published in the New York Times in January, contained a lot of PR put out by the SBU after its alleged role in the Yushchenko poisoning became public, and after allegations of corruption involving Smeshko and others, including the covert sale of cruise missiles to China and Iran, were made earlier in January at the well-connected whistleblower site, www.ord.com.ua.30 Oleksandr Turchynov, appointed to take over the SBU in 2005, considered that the story contained ‘exaggerations’; ‘not all those figures who spread [this] information about themselves carried out their obligations truly honourably. On the other hand, the influence of many honourable principled officers to avoid the spilling of blood was crucial’. He also stated that ‘the order was given with Kuchma's direct consent’.31 At the time, there wasn't the sense of crisis that there would have been if the threat had been in imminent danger of turning into reality (though it is consistent with moves being made that were doomed to fail). Neither was the sense of grievance apparent that one would expect to have surfaced in private talks with Kuchma if the Yushchenko team had suspected so much blood could really have been spilt. But, of course, as time went by and the regime did not crack down, more and more people lost their fear.

The EU Intervention

Another factor which threw the authorities off balance was that international protest had not just been unexpectedly robust, but that it had suddenly been transformed into direct intervention. By the night of 28 November, the authorities were already between rounds of talks with international leaders, and a crackdown would have been doubly difficult. The Polish president, Aleksander Kwaśniewski, later gave a very candid, if occasionally grandstanding, account of his role in leading the intervention,32 most probably because it was one of the few things he had to be proud of as he approached the end of his scandal-ridden second term. First, although he enlisted the support of the German chancellor, Gerhard Schröder, the Czech president, Václav Klaus, the Austrian president, Wolfgang Schüssel and the Dutch premier, Jan Peter Balkenende (the Dutch held the EU presidency at this time and were broadly sympathetic), this was clearly his initiative, although the harsh words exchanged at the Russia–EU summit in The Hague on 25 November helped to ensure that an initially reluctant Javier Solana, the EU's common foreign policy High Representative, would accompany him to Ukraine, and that the intervention would become an official EU mission. Kwaśniewski asserts that the presence of the Lithuanian president, Valdas Adamkus, was arranged at Kuchma's request, but actually Yushchenko had phoned him first, as well, because the two were old friends. Kuchma, however, was friends with Kwaśniewski and had phoned him on the Tuesday.33 Kuchma owed him a favour because Kwaśniewski had kept talking to him during the Gongadze affair, when the West had given up, and Kuchma therefore hoped he would now play a similar role in smoothing his forthcoming retirement. Kwaśniewski, of course, advised restraint, and Kuchma therefore persuaded Yanukovych to sit down with the delegation, which initially he had been far from keen to do. Yanukovych did not want to concede victory and had to be persuaded that the EU visit was entirely separate from that of Lech Wałęsa,34 whose supposed ‘mediation’ mission had ended up with him bounding on to the stage in the Maidan on 25 November to declare himself ‘astounded by the sentiments and enthusiasm’ of the crowd and ‘profoundly certain that this will lead you to victory’.35 Wałęsa, however, claims he also played a key role, through counselling restraint in private.36

Kwaśniewski's and Solana's first visit made the most difference. First, their very presence in Kiev provided the protesters with legitimacy and time, which were both vital ingredients in giving their action bite. They arrived just at the right time, bridging the awkward moment on Wednesday and Thursday, 24 and 25 November, when the opposition's protests were no longer building momentum and the authorities tried to declare Yanukovych the winner (the Poles had their first meeting with Kuchma around midday on 25 November). Kwaśniewski, who arrived the next day, also asserts that his presence helped forestall a big counter-demonstration by Donbas miners planned for 26 November. ‘Nine years of contacts’ meant he had mobile numbers for all of Ukraine's leading politicians, and a call to Serhii Tihipko helped to get the demonstration called off, though another version has it that it was Tihipko himself who had threatened trouble and that it was Kuchma who made the call.37 The Donetsk group had a practical reason for paying attention: the Poles had recently decided to reopen the protracted struggle for control of the steel mill at Huta Częstochowa, which the group hoped to win in 2005. The creation in March 2005 of a joint venture between the IUD and the Polish company Ziomrex, the industrial metallurgical company, to complete this and other deals was presumably a complete coincidence, despite the competition from the Mittal group. Other targets included the Walcownia Rur Jedność pipe plant, Huta Batory steelworks, and a 50 per cent stake in a refractory plant via the Polish company Ropczyce. It would be an exaggeration to say that the Donetsk clan cared more about a steel mill than they did about the political outcome of the Orange Revolution. It would not be an exaggeration, however, to say that they cared more about their potential Polish investments than they did about the alleged Yanukovych ‘issues’ that they had helped to politicise, such as the Russian language and dual citizenship.

Secondly, Kwaśniewski correctly appraised the situation in Kiev. Yushchenko's team was saying it would have nothing to do with the ‘bandits’ in power, but its position was legally weak. Yanukovych was waving his endorsement letters from various central Asian leaders, but the authorities were physically hemmed in. As Kwaśniewski said to Kuchma, in reference to Pora trapping him in his dacha: ‘If you are stuck in the middle of nowhere, it means you have no power.’ Yushchenko had the advantage of warning that ‘in a couple of days even he would lose control over the masses’; whereas Yanukovych undermined his own negotiating position by first asserting that the election was fair, and then, when Yushchenko submitted 700 appeals regarding violations in eastern Ukraine, ‘submitting [7,700] appeals from western electoral districts … in response. As a result [Kwaśniewski calmly pointed out], we had 7,700 complaints, which [clearly] meant that the election [overall] had been unfair.’ Yanukovych, moreover, was only backed up by Putin's envoy, the Duma chair Boris Gryzlov, who was often late for key meetings. After an initial tirade, mainly about hanging chads in Florida in the 2000 US election – which itself was no paradigm of democracy – Kuchma said little, while the chair of parliament, Volodymyr Lytvyn, advocated a ‘political solution’. According to another Polish account, Kuchma began by accusing the demonstrators of being ‘paid by Berezovskii and Soros’, but then used his key aide, Serhii Levochkin, to sound out the idea of a ‘packet’, that is, a compromise on the election in return for constitutional reform and his own personal guarantees.38 Previously, Kuchma had tried to trap Yushchenko with his earlier criticism of the first round, suggesting that logically that should be rerun as well.

Putin apparently rang three times during the negotiations, in frustration. The meeting between Putin and Kuchma at Moscow's Vnukovo airport on 2 December was basically a summons for a dressing-down. So the biggest achievement of the first round table on 26 November was that Yanukovych went in as president-elect and Yushchenko as his uppity challenger, but that the two men came out on an equal footing. Both sides agreed to continue the dialogue and to await the Supreme Court's decision.

The second and third round tables on 1 and 6 December were less decisive – and less constructive. At the second, Yushchenko almost made a fatal mis-step by apparently agreeing to withdraw protesters from government buildings, though he swiftly backed down when it became clear that the crowds themselves wouldn't budge. The negotiations were most notable for the fading away of the idea that the whole election might be rerun, and for the increasing prominence of the proposal to link electoral and constitutional reform. Some have credited Kwaśniewski with coming up with the idea of rerunning only the second round of the election at this time. At the third round table, given that ‘Kuchma knew that it was his last chance and insisted on including the constitutional reform into the package’, and that, ‘Yushchenko and his supporters expected an immediate dissolution of the government, which, according to all the evidence, partook in falsifying the election’,39 the opposition was arguably out-manoeuvred. Overall, however, the EU intervention was effective because it occurred at an early stage, because it was unexpected, and because the Poles led a consensus that, with America's support, even spanned the Atlantic. Russia was certainly left wrong-footed.

The Rada

As a result of the first round table, parliament assembled for a special session the following day, Saturday 27 November, in a totally different atmosphere to the one that had been prevalent when it had been thought that the session might be used formally to inaugurate Yanukovych. The balance of power in the Rada still favoured the government ‘majority’, but it was increasingly nervous and fractious. The very existence of a parliamentary opposition, however, was an advantage in Ukraine, compared to many other post-Soviet states, including Russia. In Russia, all of the four parties that won seats in the December 2003 Duma elections were backed to some degree by the Kremlin. Belarus had just organised elections in which the opposition wasn't even allowed to stand. The new Kazakhstan parliament had one opposition deputy, but he declined to take up his seat.

In Ukraine, the opposition had leverage but not control. Although the authorities' artificial and tenuous ‘majority’ in the Rada had temporarily fallen apart in September, it was in theory restored intact on the eve of the election. The three opposition factions only controlled 139 seats out of 450; the authorities proper had 182 and the Communists 59. Two nervously neutral groups, the ‘Centre’ faction set up in the spring and ‘United Ukraine’, set up in September, had sixteen seats each. By 27 November, the majority was beginning to break up, but there was as yet no mass defection to the opposition. The old guard preferred to reinvent itself, setting up a series of new factions with innocent-sounding names such as ‘People's Will’, most of which were controlled by the Rada chair Volodymyr Lytvyn, who now became a key player in the crisis.

Despite being an academic, Lytvyn had long been regarded as Kuchma's man. Lytvyn had served as chief of the president's administration through the difficult years between 1999 and 2002. His controversial appearance on the Melnychenko tapes was excused by his defenders as the necessary presence of someone constantly in the president's office, but his actual words – ‘take [Gongadze] to Georgia and dump him there’ (see page 53) seem to be urging Kuchma on. Melnychenko himself certainly thought of Lytvyn as a co-conspirator. Lytvyn was also fortunate to escape the procurator's attentions in December 2001, when he was accused of running a $10 million intellectual property scam with Ihor Bakai. Lytvyn also wrote an article that was both ominous in its attacks on the ‘myth’ of civil society and on NGOs for undermining national sovereignty, and embarrassing – as it was plagiarised from an old edition of the journal Foreign Policy. Lytvyn, however, retained Kuchma's support and moved on to another powerful post, heading the For A United Ukraine bloc in the 2002 elections, and his reward for its failure was to be controversially installed as chair of the Rada in May 2002. Lytvyn was also close to the Communists, having served as an aide to their last leader, Stanislav Hurenko, in 1989–91, and was therefore a key link in ensuring they played by the regime's rules.

However, once he was installed as Rada chair, Lytvyn began posing as a neutral arbiter. On a diplomatic tour throughout 2004, he allowed himself to be courted by the West, making a low-profile visit to Washington before the second round on 15 November, where he met Colin Powell, Condoleezza Rice, Richard Lugar, John McCain and Henry Hyde of the House International Relations Committee.40 It was unclear, however, whether Lytvyn was still Kuchma's emissary at this stage, or whether the West was right to believe he could be encouraged to become a power in his own right.

On 27 November, Lytvyn stitched together a general resolution, which, after heated debate, won 307 votes out of 450 and therefore a two-thirds' majority. Only Yanukovych's Regions of Ukraine faction and the SDPU(o) dug in and voted against it. ‘Oligarchic unity’ had gone. The resolution was backed, or at least not opposed, by other ‘clans’, such as Pinchuk's Labour Ukraine, from Dnipropetrovsk. On the specific motions, 255 deputies backed a declaration that the elections ‘took place with violations of the law and do not reflect the will of citizens’; 270 voted to censure the CEC; and 228 to order the president to appoint a new one. The Rada also attempted to draw up a list of new members for the CEC, but Lytvyn ruled the proposal unconstitutional. 307 deputies voted to hold a special parliamentary hearing on allegations of electoral fraud, while 279 voted against the use of force against demonstrators and 233 to order the relevant committee to prepare a new bill on repeat elections within two days, and incorporate many of the Yushchenko camp's criticisms, such as banning absentee voting and broadening domestic oversight. Parliament also voted to send Yanukovych and Yushchenko to the negotiating table. This time, 261 deputies voted in favour, but Yushchenko's supporters abstained. 271 deputies voted to reactivate the ongoing project of constitutional reform. Finally, 242 deputies urged the international community to be more circumspect in its interventions, which, as it was not defined who the Rada had in mind – Russia, Poland or America – was a victory for both sides.

After an initial euphoric reaction, when the opposition began to dream of actual victory, the way forward seemed less clear. The Yushchenko camp assumed that negotiations would now take place on the basis on the ‘packet’, but Kuchma kept wriggling away. One problem was that parliament had clearly overstepped its powers. Constitutionally, it was up to the outgoing president to propose a new CEC, and, it was thought, it was up to the CEC to decide whether to declare the elections invalid and move forward to a new vote. The opposition therefore upped the ante. The next day, on the evening of Sunday 28 November, they set up a ‘Committee of National Salvation’, headed by Yushchenko. On Monday, it issued four demands for Kuchma to meet within 24 hours. They were: that he dismiss Yanukovych as prime minister; immediately respond to parliament's proposal to set up a new CEC; fire the governors of Kharkiv, Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts, implicitly for their role in the 21 November fraud, but, in the words of the final resolution, more generally to take action against ‘separatists’ in southeast Ukraine, who now clearly felt the tide was turning against them.

The changing balance of power in parliament, 2004–5

| 6/10 | 6/12 | 28/12 | 24/1 | 15/2 | 15/3 | 18/3 | 11/4 | 20/6 | |

| Opposition | |||||||||

| Tymoshenko bloc | 19 | 19 | 19 | 19 | 18 | 24 | 24 | 26 | 37 |

| Our Ukraine | 100 | 100 | 101 | 100 | 101 | 91 | 81## | 87 | 89 |

| Ukrainian People's Party | – | – | – | – | – | – | 22∼ | 24 | 24 |

| Socialists | 20 | 20 | 20 | 21 | 24 | 25 | 28 | 29 | 27 |

| PIEU (Kinakh) | – | – | – | 14# | 15 | 15 | 17 | 17 | 15 |

| Centre | 16 | 15 | 14 | 14 | 12 | 12 | – | – | – |

| Lytvynisty | |||||||||

| People's Agrarians (satellites) | – | 20 | 29 | 32 | 33 | 30** | 30 | 32 | 39 |

| United Ukraine | – | 17 | 21 | 22 | 22 | 22 | 22 | 21 | 19 |

| Union | – | 17 | 17 | 16 | 15 | 13 | 13 | 14 | –+ |

| Democratic Initiatives | – | 14 | 14 | 13 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 11 |

| No Faction | 18 | 41 | 47 | 28 | 33 | 31 | 33 | 34 | 40 |

| Authorities | |||||||||

| Communists | 59 | 59 | 59 | 59 | 59 | 56 | 56 | 56 | 56 |

| Regions of Ukraine | 64 | 61 | 61 | 56 | 54 | 54 | 53 | 52 | 50 |

| SDPU(o) | 40 | 33 | 30 | 27 | 23 | 21 | 21 | 22 | 20 |

| Labour Ukraine | 30 | 18 | 18* | 14 | – | – | – | – | – |

| NDP | 16 | 16 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Democratic Ukraine | – | – | – | 14 | 16 | 18 | 18 | 19 | 20 |

| Republic | – | – | – | – | – | 10 | 11 | 11 | – |

| United Ukraine | 16 | – | |||||||

| Union | 18 | – | |||||||

| Democratic Initiatives | 14 | – | |||||||

* On 23 December Labour Ukraine and the NDP formed a joint faction temporarily to survive, then split again to create Democratic Ukraine (Pinchuk) on 20 January, and Republic on 1 February, which only lasted until 6 April.

# The faction Industrialists and Enterprise Bosses – People's Will, ‘Will of the People’ for short, was established on 21 January.

** Lytvyn's People's Agrarian Party became the People's Party on 1 March.

## Our Ukraine's numbers dropped when the new government was formed, but rose again after the Centre faction was dissolved into it on 18 March.

∼ Our Ukraine also lost members to the Ukrainian People's Party (Kostenko), established on 16 March.

+ ‘Union’ was dissolved on 31 May 2005, with most members joining the Tymoshenko bloc. (Source: regular updates from www.rada.gov.ua/depkor.htm)

On Tuesday 30 November, the Rada seemed to be backsliding. The Communists sided with the oligarchs to secure a vote of 232 to reverse Saturday's condemnation of the election and the CEC. Only 196 votes could be found to dismiss the government. Disingenuous offers and blatant sabotage options were hinted at in private. Kuchma was now arguing that ‘neither [man] can unite Ukraine’, and, on 1 December, Yanukovych suggested that both main candidates should withdraw. For a brief moment Serhii Tihipko threatened to enter the race in his stead, but this option assumed the Supreme Court would grant the authorities six months or so to prepare a new campaign. It also ignored the fact that Tihipko's PR blitz in the spring had never really lifted his ratings, despite costing millions. The ploy only served to undermine Yanukovych further – Tihipko had been his campaign manager, after all. He was now replaced as campaign manager by none other than Andrii Chornovil. Yanukovych presumably meant to demonstrate that he had supporters from both east and west Ukraine, but in fact he succeeded in yoking himself to a fake nationalist, while simultaneously complaining about Yushchenko's phantom nationalism in an election where most agreed that the issue had moved on.

The opposition responded by raising the tempo of the demonstrations once again. After several attempts, the Rada finally voted the next day, Wednesday 1 December, to dismiss Yanukovych as prime minister. However, it faced a technical difficulty. Only 222 votes could be found for the direct motion, in part because there were very real doubts about the constitutionality of the move. According to the 1996 Constitution (article 87), ‘the issue of responsibility of the Cabinet of Ministers shall not be considered … within one year after the approval of the programme of Action of the Cabinet’, which had last been done in March 2004. The Rada therefore voted, rather disingenuously, by 229 to 8, to overturn the March vote, ‘the consequence of which’, it claimed, ‘is the resignation of the government’. Except that it wasn't. Given the constitutional weakness of the opposition's position, Kuchma for the time being ignored the motion and the demand that he form ‘a government of national accord’. Thanks to Pora et al., on the other hand, Ukraine didn't really have any government, or at least not one that could issue orders from its offices.

‘Separatism’

On Sunday 28 November, east Ukrainian leaders gathered at a special conference in the Donbas mining town of Severodonetsk (just north of Stakhanov, named after the champion miner), which demanded a referendum on the federalisation of Ukraine.

Kharkiv governor, Yevhen Kushnariov, made most of the more radical statements, but this was clearly a Donetsk-led affair, and there were demonstrations in Kharkiv against him. The other clans largely kept their distance. Nor was it a particularly spontaneous outburst of local anger. Yanukovych arranged for two planeloads of foreign journalists to be flown in, and swiftly out again. Apart from general rhetoric about reviving the ‘Donetsk–Kryvyi Rih Republic’ of 1918 (then a tactical manoeuvre by the Bolsheviks), or setting up a republic of ‘New Russia’ (in the sense of Novorossiia, the Tsarist name for the broad sweep of territory from Odesa to Kharkiv), the one practical result was a referendum on local autonomy, which was briefly scheduled to be held in Donetsk on 9 January 2005, but cancelled as soon as compromise was reached in Kiev on 8 December. This was hardly radical, even in comparison to 1994, when Donetsk had held its own mini-‘referendum’ on federalism and Russian language rights. Crimea, the only region with an ethnic Russian majority, which had briefly flirted with real separatism during a six-month crisis in 1994, was largely quiescent.

Ukraine was never ‘on the brink of civil war’.41 Yanukovych's words during the round table talks indicated the artificial nature of the protests, when he said he would be happy to tell his supporters: ‘Go home to your families, we will have a legitimate legal process, we will take the issue to the negotiations table, and then all the turmoil in the regions will disappear after that. Yes, all the turmoil in the region will disappear, in the East, in the South, and everything that unfolded will disappear when we calm the people down and tell them to calm down, that everything will be taken care of, so you can just live your lives.’42 The inflaming of the separatist issue was also designed to frighten moderates away from the Maidan, and to allow Kuchma to pose as a neutral arbiter against the ‘greater evil’. The ploy certainly succeeded in briefly changing the tone of much of the coverage in the West.43

It was less successful, however, in that it led to Ukraine's leading newspaper, Dzerkalo tyzhnia (‘Mirror of the Week’) directly accusing Kuchma of organising, or at least ordering, the rally,44 though it also seemed in part a response to ‘Moscow schemes’. The Moscow mayor Yurii Luzhkov was the star turn at the rally. The four-point proposal issued by Kuchma through the National Security and Defence Council (NSDC) on 28 November showed what he had in mind. In addition to accelerated dialogue and a promise not to use force, it said, Yushchenko should agree to remove demonstrators from government buildings ‘in return’ for the rescinding of all ‘illegal’ decisions by local authorities (i.e. the ‘separatist’ councils in the east, but also potentially including the recognition of Yushchenko as president by some councils in the west) – a blatant attempt to gain a concession by graciously withdrawing a problem Kuchma had himself created in the first place. The ‘patriotic part’ of the SBU responded with a threat to take legal action against ‘separatists’ on 30 November.

It was not that the issues surrounding separatism weren't real. It's just that this time they were being fanned by cynical local leaders whose local control was then so strong they assumed they could easily put whatever genie they released back in the bottle. They also knew that if they lost, it would be somebody else's mess to clean up.

The Court

The fact that both sides left so much up to the Supreme Court hearings that began on 29 November is hard to explain. The most likely possibility is simply that the authorities were over-confident. At the 1 December round table, Kuchma had stated hubristically that: ‘Unfortunately, the Supreme Court does not have a right to acknowledge the election as invalid. Our law is multidimensional, and it is likely that our judges will provide us with some recommendations so that in the future the CEC, and the parliament, and the president could implement them.’45 Kwaśniewski had suggested televising the hearings, and Medvedchuk assumed the courts were safely under his control. Ukrainian courts had no great reputation for their independence, and just to make sure that this would not change, the authorities had launched a general pre-election clampdown on relatively independent judges,46 most notably attempting to repress judge Mykola Zamkovenko, who had freed Tymoshenko from prison in March 2001. He received a two-year suspended sentence in September 2004 for delivering judgements ‘without considering the evidence’.47 Crucially, however, the SDPU(o) had most control over the local courts, as that suited their business purposes, whereas Kuchma controlled the Constitutional Court, one of Ukraine's two ‘highest’ courts.

The other, the Supreme Court, is the highest civil court, and had not been so necessary to control in the past. The authorities also seemed to have forgotten that they had previously crossed swords with the Supreme Court during the 1999 election, when the court chair, Vitalii Boiko, criticised the CEC for not even following its own procedures (the court enforced the reinstatement of four minor candidates). Boiko, who gained a reputation for independence – which, according to Kuchma on the Melnychenko tapes, meant he was an ‘underhand bastard’ who needed dealing with – was replaced in 2002, but he had helped set the court on a relatively professional path.48

On Friday 3 December, the Supreme Court's decision unexpectedly broke the political deadlock. It dropped all pretence of equivocation, and of ‘equal fraud on all sides’, and squarely blamed the authorities. The CEC had announced Yanukovych's victory without considering outstanding legal appeals, but, more fundamentally, the court declared that ‘during the conduct of the runoff vote there were [mass] violations of Ukrainian law’, especially with ‘the formation and checking of voters' lists’ [the notorious absentee voting], and the ‘unlawful intrusion into the electoral process’ of government officials. Provisions for counting and writing ‘the reports of district election commissions’ [the government's now notorious computer fraud], the court diplomatically declared, were violated. Finally, ‘access to the mass media did not accord with the principle of equal access’. Therefore, the court concluded, ‘the violations of the principles of the electoral law … exclude the possibility of credibly establishing the actual results of the expression of the voters' will in the country as a whole’.49

Both the Kuchma and the Yanukovych camps had assumed that the court, even if it agreed with Yushchenko's case, would stop at that, and throw the problem back into the lap of parliament or the international round table. However, the court radically short-circuited the political process by ordering its own explicitly political solution – a repeat of the second round on 26 December. This would not be a new election open to all comers, or a rerun in the Donbas only. Neither would it be an election without Yushchenko or Yanukovych, as the latter had disingenuously proposed. The court's decision could not be appealed. The verdict completely changed the political game. It seemed that Yushchenko's supporters no longer had any incentive to support the compromise being worked out at the end of the week, which was offering Yushchenko a new second round in return for accepting the longstanding package of constitutional reform (i.e. reduced presidential power) after a one-year interval. Tymoshenko was now arguing that the opposition's victory was inevitable without any further concessions. One opinion poll predicted that Yushchenko would win by 56 per cent to 40. The other side did not cave in immediately, however. The regime had, as yet, no ‘exit strategy’, and had not exhausted its negative potential. Kuchma in particular, although deeply discredited as a politician, still held sufficient powers as president to act as a roadblock to further progress. He had not yet agreed to dismiss the government, and his proposals for the new CEC looked rather like the old CEC. He could still veto any bill or package of bills passed by parliament, even if it fell into the hands of the opposition.

The authorities' range of sabotage options was now narrower than it had been, but it was still formidable. They could pull Yanukovych out of the repeat vote, turning it into a ‘plebiscite, not an election’,50 and so deprive Yushchenko of the moral victory he still needed. They could also urge a boycott in east Ukraine, close the opinion poll gap with sufficient fraud, or, alternatively, make their fraud so obvious that the Supreme Court might invalidate yet another election. The authorities blocked parliament's attempt to pass a new election law to establish fairer process on Saturday 4 December, as a result of which parliament was initially adjourned for ten days. From 5 December, protesters' numbers began to grow again. One final push was still needed.

In private, however, Kuchma was putting out feelers about his desire for immunity and financial security. At the time, the first seemed to be no real problem, as Yushchenko's camp had offered it several times already. In the long term it would become more problematic, however, as he got no concrete promises on paper. The second was also possible, unless he got too obviously greedy. He had already asked to keep his dacha and his yacht. More difficult was Kuchma's reported demand that Yushchenko drop his threat to reverse controversial privatisations that benefited his supporters, such as the notorious sale of the giant Kryvorizhstal steel mill in June. However, one thing was clear: Kuchma's obvious self-interest undermined the more serious threats he was making via his entourage.

The Compromise

Parliament sat again on 8 December. When the Orange Revolution was over, Our Ukraine put out a booklet called ‘Seventeen Days, Which Changed Ukraine’, assuming that the protests, which began on 22 November, ended with some kind of final victory on 8 December. Others would argue that the revolution continued until the third vote on 26 December, or until Yushchenko's inauguration on 23 January – or even that it is still not over and will have to go on for years. Radical critics, who at the time included Tymoshenko, also argued that Yushchenko gave in to his natural instinct for compromise and gave away too much just when victory was in sight, and that Medvedchuk won in the end.

Things looked different at the time, however. The Supreme Court judgment mandated a new election, but no one knew if it could be held on time. Technically, the process could be dragged out for ninety days. Kuchma was still refusing to create a new CEC and sign a new election law, and without a clean third round the opposition might be no further forward. The Zoriany team might no longer be at work, but without new authorities overseeing the count under new rules, all of the other voting ‘technologies’ could be reapplied. Kuchma's meeting with Putin on 2 December was most notable for Putin's veiled threat that: ‘A re-vote could be conducted a third, a fourth, a twenty-fifth time, until one side gets the results it needs.’51 The threat was not so much of indefinite delay, as of a stalemate resulting from the authorities clinging on to their vestigal ‘administrative’ power. The Severodonetsk meeting was also clearly a marker; the issue was not real separatism now, but the threat that the authorities might exploit the issue if they didn't get the exit strategy they wanted. And the longer Kuchma refused to form a new government, the more damage would be done to the economy, which faced both macroeconomic risks such as trade disruption, confidence in the currency and so on, and increasingly obvious plunder by the more unscrupulous members of the old guard. The opposition wanted to do things legally, but they didn't have a majority in parliament. More exactly, their near majority had been taken away from them in 2002.

The regime was losing its fragile unity, but only a handful of figures such as Oleksandr Volkov had at this stage defected to the Yushchenko camp. The likes of Pinchuk, Akhmetov, Yaroslavskyi and the host of smaller figures (it was estimated that a staggering 300 out of 450 Rada deputies were dollar millionaires) wanted to wash their hands of the hard-line scheming of Medvedchuk and Kliuiev, but their main priority was their own survival. Medvedchuk's constitutional reform project was therefore revived with a transformed purpose, which was no longer that of forcing a would-be president Yushchenko into a cul-de-sac of limited power, but of transforming the Rada into a safe haven for the old elite, which would, it was hoped, feel less like a retirement home and more like a business club. Yushchenko could swallow constitutional reform; he had promised it to Moroz, and his aides believed he would now be a revolutionary president unbound by Lilliputian restraints, and that whatever concessions were made would be won back by victory in the Rada elections due in 2006.

Deputies therefore voted for a ‘packet’ on 8 December: constitutional reform along with a new election law, local government reform and Kuchma's final agreement to dismiss the discredited prosecutor general and chair of the Election Commission. The ‘packet’ was voted on as a whole, and received 402 votes out of 450. Significantly, most of the enthusiasm was on the government's side. All the then ‘majority’ factions voted in favour of the ‘packet’, but this included only 78 out of 101 members of Yushchenko's Our Ukraine bloc, and only one out of nineteen of Tymoshenko's supporters. Tymoshenko herself did not vote, on principle. More mysteriously, neither did Yushchenko, although he was present in parliament at the time. Kuchma and Lytvyn signed the ‘packet’ in the Rada's main hall, there and then, supposedly to demonstrate national accord, but their haste also demonstrated the extent of their relief. More practically, the opposition simply did not trust Kuchma. In private, he might sign the Constitution bill and forget about the other measures. He had certainly ratted on many other similar deals in the past.

The way forward to a new election on 26 December, and to what all sides assumed would be Yushchenko's inevitable victory, was now clear. The CEC was reconstituted with a new chair, the respected Yarolsav Davydovych and four new members. On 15 December, the 225 TECs and 33,000 individual Polling Station Commissions (PSCs) were reconstituted on a streamlined, bipartisan basis, with equal representation for Yushchenko and Yanukovych supporters. It would also now be impossible to dismiss any member within two days of the new vote (many of Yushchenko's ‘trustees’ had been booted off at the last minute in the previous rounds). That said, the Yushchenko team didn't have enough ‘trustees’ to staff all the commissions in the time available, and often had to rely on students. Several stable doors were bolted to prevent the more obvious ‘technologies’ used in the previous rounds. Much tighter restrictions were placed on the issue of Absentee Voting Certificates (188,000 rather than 1.5 million), on voting with mobile ballot boxes, and on the printing of surplus ballot papers – the last was a normal feature of most elections, but not with the millions of extra copies produced in previous Ukraine elections. Absentee voting would be restricted to the ‘category one’ infirm, disabled or injured, who were actually immobile. Much more information would be required from the CEC to track the voting summation process, although unfortunately not down to the PSC level. The CEC would also have to publish this information in the mass media.

The constitutional reform bill, technically number 4180, was supposed to resemble the package agreed between Yushchenko and Moroz, but was actually a close copy of the one that had failed in April. Amendments have to be passed twice, at consecutive Rada sessions. The Constitutional Court had to pretend not to notice. The changes made by the bill were due to take effect on 1 September 2005, if the necessary reforms to the system of local government were made by then (these mainly stipulated that local leaders should be directly elected, rather than appointed by the president, as they had been since 1994). If not, bill 4180 was to take effect from 1 January 2006, regardless. Under the new system, parliaments would serve for five years rather than for four. The president's powers to dissolve parliament remained limited. The next parliament would be wholly elected by proportional representation on national party lists, and the barrier for representation would be lowered from 4 per cent to 3 (this confirmed a proposal passed earlier in 2004). Elected deputies would serve a so-called ‘imperative mandate’, meaning that if they were elected, say, as Our Ukraine or as a Communist, they would have to remain as such or lose their mandate. This provision had long been backed by the opposition and was designed to stop the constant splitting and reinvention of factions that has plagued Ukraine since independence. Critics said this measure would make deputies too dependent on authoritarian party leaders, that power would pass to backroom cliques rather than to parliament as a whole. In addition, Deputies would be unable to take other well-paid positions, or serve simultaneously in the government. The first provision was not well-defined, but was a good idea, although it produced an unseemly row when Oleh Blokhin, the successful national football coach who also served as a deputy for the SDPU(o), having been first elected as a Communist, was forced to resign in March. (Blokhin was arguably the USSR's best-ever player. He won the European Cup Winners' Cup twice with Dynamo Kiev and was named European Footballer of the Year in 1975. He won 112 caps for the USSR and scored 42 goals – both records.) The second provision was a bad idea that negated the basic idea of party government.