9

9

9

9

When I was first learning how to sew and started showing off a skirt or something I had designed and made, I told someone that sewing was simply the essence of common sense. You just had to stare at your idea from all sides and figure out how to make it exist. In retrospect, I was using the term common sense the way many people do, with a certain amount of self-satisfaction, a pinch of false humility. Because, fundamentally, sewing is really engineering, and like an engineer, you have to picture things three dimensionally—you have to flip things over in your head and turn them inside out to see what you’re doing. You have to take things apart and put them back together. But you also have to muster all your patience as you pin, and iron, and stitch and stitch and stitch. And then it’s design, and it’s art, too. You can play with colors like a finger-painting kid and still manage to maintain your image of straitlaced practicality, if that’s your thing.

No, sewing is not just common sense, but a commonsense knowledge of how things work is most of what you need to figure it out. I have tried to explain things in this chapter so that you know why they work the way they do—to give you a practical understanding of the properties of fabric and fiber, whether you want to design clothing, mend an elbow, or make a quilt.

—R

Grain, Gore, Right, and Wrong: A Handful of Basic Sewing Terms

Grain: A term borrowed from woodworking, grain refers to the direction the fabric’s threads are running. Unlike wood, however, woven fabric usually has two grains: the threads running vertically and the threads running horizontally. Most of the time, you can use both grain lines interchangeably, unless the fabric has a directional design (like stripes) or an unusual weave (like a twill).

When you pull a piece of fabric on the grain line, it won’t stretch very much. If you pull the fabric on a line diagonal to the grain (on the bias), however, it will stretch considerably. This stretchiness, or give, makes a big difference in how clothing fits! For a twill, pick the grain line with the least give as your reference for laying out pattern pieces.

Knit materials are stretchy in every direction, but you still need to pay attention to grain lines—just follow the lines of the knitting.

Right Side/Wrong Side: Printed fabrics and unusual weaves have a wrong side and a right side. If it’s not clear which side is supposed to be the right side, pick your favorite and use it consistently.

Seam: A line of stitching joining two pieces of fabric is a seam (see page 168).

Allowance: Extra fabric added to seams and hems to prevent fraying. Usually 1⁄2 inch for seams (see page 168) and 3 inches for hems (see page 174).

Hem: The bottom edge of a garment is generally called a hem, but hemming also refers to a particular kind of stitch (commonly used on skirt hems; see page 174).

Basting: Long running stitches used to temporarily hold fabric in place before stitching it (see page 170).

Gore: The truncated-triangle-shaped pieces of fabric used to create the panels in skirts (and umbrellas).

Dart: A tapered tuck used to shape a garment (see page 178).

Useful Tools

You can, in fact, sew with just needle and thread, but a few other tools make it a lot easier.

For starters, it’s worth having a wide variety of sewing needles in different thicknesses and lengths. You’ll also want sharp sewing scissors to cut fabric without it moving around. You’ll need plenty of pins and an iron (see page 176). A seam ripper comes in handy, even if just to remove itchy tags on clothing. You’ll sometimes want a yardstick; a tracing wheel and paper can be very helpful for transferring patterns to fabric, but they’re not crucial.

And, of course, a functional sewing machine is a fabulous tool. You can sew without one, but there’s a very good chance that you can acquire a decent old sewing machine for free or next to nothing, if you’re really interested.

Seams

The fundamental principle of sewing: take two pieces of fabric, place right sides together, and line up the raw edges you want to sew. Stitch 1⁄2 inch or so from the edge (this distance is the seam allowance).

Some seams are formed in other ways. Topstitching refers to sewing from the top—that is, the right side of the cloth, with the material lying flat. Usually you’re topstitching a seam you already sewed, to reinforce it. A serged seam is stitched by a special machine, which simultaneously reinforces and trims the raw edge to keep it from fraying.

Less common, a French seam is an enclosed seam with no raw edges showing, even on the inside of the garment. Basically, a French seam is stitched twice: First you stitch wrong sides together halfway between the seam line and the edge. Then you fold the fabric back and stitch right sides together on the intended seam line.

Seam Allowances

Whenever you stitch two pieces of fabric together, you need to allow for extra material, called a seam allowance. Seams need to be well back from the edge of the fabric, or they will fray and rip out. For most cloth, 1⁄2 to 5⁄8 inch is the standard seam allowance. Very coarsely woven or knit cloth (picture burlap and sweaters) requires a large seam allowance, whereas a tight, fine weave might need only 1⁄4 inch. The amount of strain the seam carries also affects the size of the seam allowance. You want a generous seam allowance on a corset, for instance.

Basic Stitches

Sewing machines are excellent devices, but I can’t tell you how yours works, and there are always things you’ll have to sew by hand. Hand sewing can be a pleasant and efficient process once you catch the rhythm of it. For any given stitch and situation, you should experiment to find the easiest way to hold the fabric and needle. Sometimes just changing the orientation of the fabric can make it much easier to stitch. Right to left? Up to down? When you’re comfortable and get into a rhythm, your stitches become much more even and regular.

To avoid tangles and frustration, cut your thread no longer than an arm’s length (or two arms’ lengths, if you’re doubling it). For shorter work, cut your thread about three times the length of the finished seam, or twice the length for a basic running stitch.

Securing the Thread

On fine, tightly woven fabrics, a knot in your thread will secure it on the underside of the fabric. On looser fabrics, a loop is more secure. I often sew with doubled thread. Load a thread through your needle, then hold both ends of the thread together and tie them in a knot. Make your first stitch as usual, then when the needle comes back to the underside of the fabric, slip it through the loop formed by the two knotted threads. This is a very secure anchor.

When you’re done stitching and ready to tie off your thread, poke the needle through to the underside and slide it under your last stitch. Twist the needle around the thread right where it came through the fabric and pull to form a knot.

Running Stitch

The running stitch is the basic up-and-down stitch: Poke the needle down through the fabric, then poke it back up a little farther along. Because the stitches all go one direction, the fabric can bunch up and slide along the thread when it’s pulled taut. Running stitches don’t make a secure seam, but they’re useful if forming gathers is your purpose. They’re also quite quick to make—you can load several stitches on your needle before you pull the thread through.

Sometimes when you’re sewing a particularly tricky spot, pins won’t hold the fabric securely enough for you to sew it properly—or maybe you want to make a quick temporary seam and check how the garment fits before committing to a real seam. In these cases, running stitches spaced 1⁄4 inch apart can hold the fabric together for a bit and then be undone quite easily. This is called basting.

Running stitches are also used for quilting, once the layers of the quilt are assembled and tacked in place. With multiple thicknesses of cloth, puckering and gathering are less of a worry.

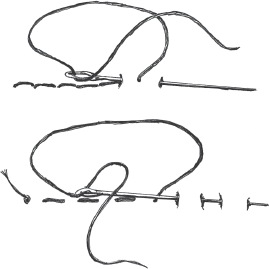

The basic embroidery stitch (top) backtracks to form a secure, solid line. Running stitch, bottom.

Backstitch

The backstitch solves the gathering problem of the running stitch by going one step back, then two steps forward. Secure the thread on the underside of the fabric, then bring the thread up through. Poke the needle down through the cloth 1⁄8 inch in the opposite direction from where you want to go, then bring it back up 1⁄8 inch ahead of the starting point. For each backstitch after the first, you can poke the needle down through the same hole as the previous stitch, or right beside it. The finished product will look like a continuous line of end-to-end stitches. The underside of the fabric will look a little messier, with stitches leapfrogging each other.

You can, of course, modify this stitch in any number of ways. The 1⁄8-inch spacing is certainly adjustable, and the stitches don’t have to meet each other. The inverse stitch, done carefully, forms a line that looks like a twisted rope—in embroidery, it’s called the stem stitch.

Even with the backstitch, you must be careful to build in a little flex. Pulled perfectly taut, the backstitch will bind the fabric more than the average machine stitch. Hold the fabric taut in your hand as you’re working or put it in an embroidery hoop. If your fabric is slacker than your stitches, the stitches will bind it and the seam won’t lie smooth.

Whipstitch

The whipstitch is especially useful when a straight row of backstitches would be too binding. It’s easy and quick, and you’ll need it for hems, attaching patches, and stitching seams you can access only from the outside. Sewn with bold thread, it has a decorative charm that manufacturers try to emulate whenever they want something to look adorably handsewn.

Secure the thread and pull it up through the fabric at a spot 1⁄8 inch below the edge of the fabric. Pull it up through the fabric again, this time 1⁄8 inch to the side of the spot you brought it through before. Repeat.

If your fabric doesn’t have an edge, you’ll have to poke it down through the fabric at an imaginary edge line. If you poke it through the fabric directly above the spot where your stitch came out, you’ll wind up with a row of neat little vertical stitches with angled stitches on the reverse side of the fabric (basically an inverse hemstitch).

Blanket stitch on the left, whipstitch on the right.

Blanket Stitch

The blanket stitch is a modified whipstitch. It looks great as a finishing stitch on the edges of blankets, of course, but by varying the distance between stitches and the stitch lengths themselves, you can create patterns fancy enough for the edges of silk handkerchiefs, too. Because obviously you have dozens of silk handkerchiefs languishing for want of embellishment.

I like to start with the edge of the fabric down. Secure the thread on the underside and pull it up through 1⁄4 inch above the edge. Make the next stitch by pulling the needle up through a spot 1⁄4 inch to the side of the previous spot. This time, be sure your needle passes over the thread as in the illustration above. Tug it gently into place and repeat.

The very first stitch will be a bit slanted, but the others will be nice and square. If you’re sewing a blanket, you can leave the first stitch slightly slack and catch it in the final stitch when you come all the way back around.

Hems

Hemming is a preeminently useful skill, since it’s necessary for lengthening and shortening ready-made clothes as well as constructing new ones. It’s also a frequently demanded repair. Hemstitching is not just for the bottoms of clothes, either—it’s useful on sleeves, curtains, and tablecloths, too.

You need to leave at least a couple of inches for a hem. A very small hem allowance creates awkward stiffness in the hem owing to the tightly folded fabric, which braces the material. The heavier the fabric, the more hem allowance you should leave. Extra material in the hem will also give you leeway should you wish to lengthen the garment later.

Seams bind and tighten the fabric on which they’re sewn, preventing the weave from shifting and stretching slightly in the direction of the seam. Usually this is a good thing, but not in the case of hems. An ordinary seam on the edge of the fabric will cause it to stiffen and pucker, so it doesn’t drape smoothly.

Thus hemstitching is loose—the individual stitches are about 3⁄8 inch apart—and the stitches themselves are perpendicular to the hem. This way they don’t line up and bind the fabric. Hemstitches don’t bear a lot of weight or strain, so they can get away with being delicate.

Good hemstitches are also invisible. When the needle dips down to the outside of the garment, it only catches a thread or two before coming back to the wrong side. A tiny pucker, eased with ironing, should be all that’s visible.

First, determine where you’d like the edge of the garment to be. Try it on inside out and have some help pinning up the raw edge of the fabric so the bottom is level with the floor (or properly angled if that’s what you’re after) at the desired height. Pinning can be a little bit tricky on the hem of an A-line skirt, since the raw bottom edge will be wider than the part you’re pinning it to. Try to keep the excess evenly distributed, and pin frequently.

You now have a folded edge on the bottom of your garment. If you’re working on a full A-line skirt, it might help you to iron the pinned fold now to keep the evenly distributed excess fabric in place.

Next, fold under the raw edge about 1⁄2 inch, and pin it in place. Choose a thread that closely matches the material. Anchor the thread to the inside fabric and make a tiny downward stitch, dipping the needle under just a few threads of the exterior fabric before coming back up through the folded-down edge of the inside fabric. You’re basically making a whipstitch that barely snags the outside of the garment.

When stitching a hem, the tiny vertical stitches should be barely visible on the reverse side.

After stitching the entire hem, iron it carefully. Use steam on cotton or wool to relax the fibers and ease any excess material into place.

On Pins and Irons

The fact of the matter is, most of sewing is planning and engineering. The rest of it is pinning and ironing, with a tiny bit of actual stitching thrown in. First you must pin your pattern pieces before you can cut them. Then you must pin your fabric pieces together before you can stitch them. You pin when you’re fitting, when you’re hemming, and when you’re mending. If you’re really an A student, you might even baste everything you pin, and then sew it again for real.

The point of all these pins is to keep the fabric from sliding around. You start stitching together two equally long pieces of fabric and by the time you reach the end of the seam they will not—I guarantee you—still match up, unless you’ve pinned them at reasonable intervals. A reasonable pinning interval is a few inches for straight, flat seams parallel to the grain. If the fabric is cut at an angle to the grain (aka on the bias) or if you’re negotiating seam intersections (darts, gathers, sleeves, or other interesting topography), you might have to pin every 1⁄2 inch or less, and probably baste, too.

Sometimes, even then, you might find yourself dealing with a heavy wool material of an unusual weave that stretches more in some directions than in others and at least one edge of every gore in the skirt is on the bias, and no matter how you pin, the skirt pieces will not match up. That’s why you leave a very generous hem allowance, especially on your wedding dress.

Ironing is the other side of pinning. You should iron your material before you lay out the pattern pieces, and later, your seams will not lie smooth until they have been ironed open.

To press open a seam, lay it flat on the ironing board with the raw side facing up. With your fingers, separate the two raw edges and fold them back in opposite directions (like opening a book). Come behind with the iron, smoothing them into place.

Occasionally it is necessary to press both raw edges together onto one side of the seam—for narrow darts, for example. But most of the time, even when the finished garment will be folded on the seam, you still want to press the seam open first.

Buttons

Because it’s easier to move a button than a buttonhole, you should sew your buttonholes first. Cut a slit in your material large enough for the button to pass through, erring on the small side (at first). Seal up the raw edge of the slit with very tight, close whipstitches. When you’re almost all the way around, check the button again. The whipstitching can change the way the hole fits over the button. Adjust the size of the buttonhole now, if you need to, then finish whipstitching.

When sewing on a button, use double thread and anchor it solidly. Stitch through the loops or the buttonholes more times than you think necessary—dozens of times, at least. Be aware that your stitches can gradually shift the button’s position as you’re working, so check regularly to make sure the button is staying centered on the spot it’s supposed to be.

If you’re designing something from scratch, remember to leave extra material for the button overlap—and even more if you want to double the fabric back to make a sturdy button placket.

Darts and Tucks

The tricky thing about darts and tucks is that they turn flat fabric pieces into three-dimensional surfaces. That, of course, is why they’re so useful! But it also means that getting them to look smooth and flat is a bit of a chore because, in fact, they aren’t flat.

Take darts. First, transfer or draw the dart lines onto the inside of the fabric—it should look like an isosceles triangle with a line bisecting it. Your job is to stitch together the sides of the triangle. Fold the cloth on the midline so the midline forms a ridge (not a valley). If you had X-ray vision, you could see that the other two lines match up perfectly. Pin the cloth in place and stitch along the line. Be especially careful at the point of the dart. Any veering or puckering will be very noticeable when the fabric is opened up.

To form a dart, fold the fabric on the center line (dotted) and stitch the solid lines together.

If the dart is more than 11⁄2 inches at the base, you may want to trim it parallel to the seam, leaving 1⁄2 inch of seam allowance. Otherwise, press the dart to one side or the other. Most darts come in pairs, so be sure to press them in symmetrical directions. Pressing will be rather tricky at this stage, since the material is no longer flat. Try pressing it over the narrow end of the ironing board or the end of a table.

There is another type of dart that is shaped like a diamond. It’s essentially two darts stacked and shows up in waistlines.

To form a tuck, fold the fabric on the dotted line and stitch the solid lines together.

Tucks are a bit easier because they have no point to contend with. When pressing them, take care not to press the fold beyond the end of the stitching, unless pleats are your intention.

Embroidery

Most of the basic hand-sewing stitches are easily adapted to decorative purposes. Use embroidery floss or fine yarn to give your labor some emphasis. Mark your designs directly on the fabric with light pencil first, or just freehand doodle with your needle. It’s a good idea to practice new designs on scrap cloth first to get the feel of them.

Since embroidery floss is composed of multiple tiny threads only loosely held together, tangles and knots form easily and are immensely frustrating. Save yourself some trouble: Cut your thread on the short side and use a needle with a large eye.

An embroidery hoop holds the fabric taut for you, which makes it easier to get precise results on tightly woven fabric. Move the hoop around to keep the area you’re working on in the center of the hoop. Embroidery hoops are useless for stretchy material (and yes, you can embroider stretchy material—it will just stretch less and/or pucker in the embroidered areas).

I’ll quickly describe a handful of fun embroidery stitches, but you’re free to invent your own. To make a chain stitch, for instance, bring the needle up through the material and back down through the same spot or very near, leaving a loop of thread. Bring the needle back up through the material at the spot where you want the next link in the chain. Hook the needle through the loop, and poke it back down where it just came up, once gain leaving a loop to catch in the next stitch. Gently tug everything into place. Repeat.

To make a flower petal or leaf, start making a chain stitch, but don’t make a second loop. Just catch the first loop and poke the needle back down to tack the loop in place. If you form a chain stitch but don’t poke the needle down right next to where it comes out, you’ll make a branching fernlike stitch.

You can fill in larger color blocks with a satin stitch. These are just large parallel stitches that traverse the area from one edge to the other, laid down side by side to fill in a space. If the stitches get too long and start sagging and looking bad, you can weave a few perpendicular stitches across the satin stitches to hold them in place.

The stem stitch (an inverse backstitch) and the chain stitch are useful not just for drawing lines but also for filling in larger areas.

Alterations

One of the easiest and most gratifying ways to create unique and stylish garments is to start with something much less unique and stylish, and modify it. Conveniently, it’s also more economical than purchasing new fabric by the yard. Knowing how to alter clothing for fit also expands your options significantly.

Width

You can easily fix a skirt waistband that rides too high or low, provided you renegotiate any zippers. Determine the new size you’d like the waistband to be, and where it will fall on your waist. With a seam ripper, pick out the stitches attaching the waistband to the skirt.

To narrow the waistband, sew a tuck of the appropriate size into the back middle of the band. Then, you have several choices for how to narrow the skirt itself. You can either sew a pair of darts or tucks into the back of the skirt, or take in the preexisting seams. The total width of the darts or tucks should be the same as the width of the waistband tuck. Sew the waistband back on.

To lengthen the waistband, you will probably need to add some material. Either find a scrap of similar material, and stitch that onto the end of the old waistband (or into the middle, for symmetry), or construct a new waistband from scratch. The skirt itself will need to be trimmed to fit the new waistband. Since skirts usually widen as they descend from the waistband toward the hip, you need to locate the point where the skirt reaches your desired width, mark it, and then trim off the top 1⁄2 inch or so above that point. Be cautious here. Even a tiny amount of trimming can dramatically widen the waist opening of the skirt, depending on its cut. In any case, the skirt will slacken and sag when you trim it as its lengthwise seams unravel slightly, but reattaching the waistband will restore its structure.

Pants are significantly more difficult to alter in the widthwise dimension because they can’t simply be adjusted up or down on the body like skirts. In most cases, however, they can be taken in by tucking the waistband and taking in the side seams, as described for skirts. There is usually not enough excess material to let them out. You could certainly take apart the side seams and insert strips of material, preferably colorful tie-dyed fabric from a Grateful Dead tapestry.

It’s not difficult to take in the legs of a pair of pants to create skinny jeans. Put the pants on inside out and determine how much to take them in and where. Pin them while they’re on you, so you can check to make sure you can still get your feet out of the bottom. Take them off and mark the places where the new seams should go. Taper them gradually, or you’ll get a knicker-like effect. If you can, take in only one seam on each leg: The seam that isn’t topstitched or the seam on the side of the leg with the most flare (in both cases, that’s usually the outside seam). If you’re taking in a lot of material, you may want to take in both leg seams. Stitch the new seam on the marked lines, then rip out the old seam. Press the seam open. You may need to undo the hem and rehem it for a clean, finished look (on denim, this is usually just a topstitched rolled hem, so not a big deal).

To narrow shirts and blouses, take in the side seams or add darts. Do so with some caution, however, or the shoulders may wind up looking out of balance and bunchy when the shirt no longer has so much fullness and drape. Taking in the shoulders is a bit of a trick because it involves taking off the sleeves.

Length

Shortening pants, skirts, or sleeves is usually fairly easy. In most cases, you can simply undo the current hem, fold the fabric up farther, and rehem it.

Sleeves with cuffs are slightly more tricky. First, note how the tucks or gathers are distributed. Remove the cuff and either trim the sleeve or just slide the cuff farther up over the end of the sleeve. Then pin the cuff back on, being careful to distribute the tucks or gathers as they were before. Topstitch the cuff in place.

To lengthen cuffed sleeves, feel how much seam allowance is on the end of the sleeve inside the cuff. You can maybe lengthen the sleeve a bit by turning a 1⁄2-inch sleeve allowance into a 1⁄4-inch sleeve allowance, but sturdiness may be sacrificed. At least reinforce the raw edge of the fabric with zigzag stitching, but that only goes so far.

To lengthen pants or a skirt (or hemmed or lined sleeves), you’ll need to check that there is enough excess material built into the hem. You might be able to eke out a little more length by using hem tape. Stitch the edge of the fabric to the hem tape, and then hemstitch the hem tape.

Mending

Many holes in garments aren’t holes in the fabric, but rather places where the stitching has ripped out. These sorts of holes are the easiest and least obtrusive mending jobs. If the garment isn’t lined, you can just turn it inside out, fold it at the seam, and stitch along the existing stitching line over the ripped-out section. Be sure to overlap the intact stitches by 1 inch or so on either side. You can do this even on serged or French seams. If you follow the old stitching line exactly, use matching thread, and don’t make the stitches so tight that the fabric puckers, your mending will be perfectly invisible.

If you can only access the seam from the outside of the garment, you can still make a tidy, nearly invisible repair. For a small hole, 1 to 2 inches, make little running stitches on the seam lines back and forth across the hole. Be sure that each stitch is passing through only one layer of the material. Pulled taut (but not puckering), these stitches will be invisible. Anchor the thread 1 inch from the torn spot on either side.

For a larger hole, you’d be wise to pin the edges together, to avoid stitching the seam crookedly. You’ll also want to use a backstitch, to prevent the fabric from gathering and puckering.

Patching

There are two basic ways to patch a hole: from the inside, and from the outside. Small holes with some threads still connected can be unobtrusively patched from the inside. Larger, messy holes are better patched from the outside, so they don’t snag and reopen. You can, of course, put a patch on both sides, to prevent snagging on both sides of the cloth, but then you must start to worry about the weight of the patch itself straining the original material.

In fact, being able to decide whether a patch is worthwhile is one of the key skills of patching. The chafing edges of the patch and the extra stitches themselves put an additional strain on already-worn material. That said, patching usually takes just a few minutes and can extend the life of a pair of work jeans for months or years, definitely a worthwhile attempt. You can also apply a preemptive patch. My mother used to do this for the knees of all our sweat pants, and the trend is well established on the elbows of professorial jackets.

Consider the original material quite closely. If it’s becoming brittle or all-over thread-worn, you might wind up with more patch than original garment, which isn’t necessarily a reason to give up hope, depending on your aesthetics. Be particularly wary of patching stretch denim, as once it starts to wear out, it goes downhill quickly. Delicate fabrics will no longer drape the same way once they are patched, but with some care, you can minimize the effect. Loose-knit fabrics, like sweaters, are often best patched with matching yarn woven across the hole (darning).

You will want to find a patching material that matches the original in terms of thickness, weight, stiffness, and stretch. A heavy patch will cause the garment to pucker or stick out oddly, or tug the threads out of their weave. A thin patch will wear out more quickly than the original material.

Your stitches themselves should also match the fabric type. Even on tightly woven fabric, try to avoid tight straight lines of stitches, as they will bind the fabric, making the patch not only uncomfortable but also more likely to rip out. Instead, use whipstitches or zigzag stitches to build in some flex.

INTERIOR PATCH

An interior patch is an excellent way to mend the tiny holes formed at the upper corners of your back pockets (just don’t stitch through the pocket itself), moth holes, or small rips from barbed wire and brambles.

Cut your patching material to be 2 inches larger than the hole in all directions. You can trim it down later. Keeping the garment right-side out, slide the patch up inside behind the hole, and pin it in place. With either a machine or by hand, run stitches around the outside of the hole (on good cloth, not the frayed edges). Then trim the loose edges and tack them down with zigzag or whipstitches. It wouldn’t hurt to put another row of reinforcing stitches 1⁄2 inch from the edge of the hole, if there’s a good deal of tension and friction in that area.

Now turn the garment inside out and trim the edges of the patch, leaving a 1⁄2 inch of fabric beyond the outer stitches.

EXTERIOR PATCH

The exterior patch is almost like an inverse of the interior patch, except that appearances are more important. Before stitching on the patch, you will want to fold the edges under 1⁄2 inch or so to avoid raw fraying edges on the outside—this means you need to cut your patch size to be at least 1⁄2 inch larger than the hole, plus 1⁄2 inch extra to fold down.

You might also want to avoid stitching the fraying edges of the hole directly to the patch, if the idea of extra stitching lines on the patch is bothersome to you. Instead, you’ll want to reinforce the edges of the hole before covering it with the patch. Trim away the loose threads and run zigzag or whipstitches first around the very edge of the hole and then 1⁄4 inch from the edge. Position the patch, pin it, and stitch it down at the edges. Put in another row of stitches, this time 1⁄4 inch from the edges.

For the greatest security, and if you don’t mind how it looks, pin and stitch the patch over the hole as described, then turn the garment inside out and stitch all the fraying edges directly onto the patch, leaving as many of the fraying threads intact as you can without them being annoying and snaggy. Put in a generous amount of reinforcement stitching 1⁄4 inch and 1⁄2 inch from the edge of the hole.

Darning

Large, open knit garments, like sweaters, are vulnerable not so much to fraying as unraveling. So mending them requires you to take a different tack: darning, which is essentially a weaving process. You can also darn certain types of holes in denim—like the knee holes that still have lots of horizontal threads crossing them.

Choose yarn the same thickness as the garment’s yarn. With a large blunt needle, start laying down the warp threads, keeping the stitches a safe distance (1⁄2 inch, or less for tighter knits) away from the hole. The stitches should be slightly loose—not baggy, but far from tight. If they are too tight, they will simply unravel the sweater further.

When you have covered the hole entirely with warp threads, plus 1⁄2 inch on each side, you can start laying down the weft. These stitches are just like the warp stitches, except you have to weave them under and over every other warp thread. For each weft stitch, go under the warp threads you went over on the last stitch, and vice-versa. When you’ve completely woven across the warp threads, push the needle through to the wrong side of the garment and anchor the end by tying a little knot onto a loop in the sweater.

When darning the heel of a sock or the elbow of a sleeve, it can be helpful to push a light bulb inside to give you something to work against. The light bulb also ensures that the darned hole will curve out like the heel of a sock is supposed to.

Decorative Modifications: Pleats, Ruffles, and Other Trim

I once found an adorable 1960s corduroy minidress at Goodwill. The dress fit perfectly, but the stiff, A-line, super-short skirt was just too big a liability. I found a nice contrasting corduroy material and made a heavy full pleat, which I stitched to the bottom of the dress. The dress, now at a comfortable length, also gained some amazing saucy swish and the weight of the trim improved the way the entire dress draped.

Another time, I found a 1970s wrap dress made of gauzy layers. The bodice was an atrocious, unflattering pile of ruffles. I cut it off and stitched a waistband on to the skirt, which actually had a stylish two-layer hem. The layeredness, however, needed a little more definition, so I embroidered both layers of the hem with thick black thread. (In fact, I invented a special sort of knotted, twisted blanket stitch, which I have since forgotten how to do!)

Then there were the sleeves on my wedding dress. (Sleeves on a wedding dress?! If you’re getting married on the coast of Oregon, yes!) The heavy wool material just didn’t hang right. On a whim, I grabbed some leftover pleat trim and pinned it onto the sleeves. Instantly they looked finished and draped just right.

The point is that trim plays two roles. It can visually transform a garment, but it also builds weight into the fabric, which becomes momentum when you move. And momentum is swishing, draping, swirling—fun things to have in your toolbox, whether you’re designing something from scratch or modifying another garment.

Ruffles are an obvious choice, and they don’t necessarily have to be gingham bits of country charm on the hem of your skirt. Ruffles exaggerate the stiffness of your material; soft fabrics make less puffy ruffles. You can either hem a ruffle, fold it double, or (on delicate fabrics) give it a tiny rolled hem.

Cut a strip of fabric as wide as you want the finished ruffle to be, plus seam allowance on one side and hem allowance on the other. It needs to be one-and-a-half to three times as long as the fabric edge you’re attaching it to—the longer it is, the more folded and fluffy the ruffle will be. If it’s too short, it won’t look like a ruffle, just a badly sewn strip of fabric that didn’t really match up right. You might have to sew a few strips together to be long enough.

To gather the ruffle, baste it with loose running stitches (1⁄2 inch) 1⁄4 or 1⁄8 inch from the raw edge. If you’re stitching a long ruffle, it might be easier to baste and gather the ruffle in sections. Pull on the ends of the thread until the fabric bunches up to the right length. Spread the gathers out evenly, pin in place, and sew. Topstitching also works well on ruffles. In either case, don’t bother pressing the seam open; just press it away from the ruffle.

Pleating is basically controlled gathering. The fullest a pleat can reasonably be is three times the length of the material you’re stitching it to. Prepare your material as for gathering, above. Decide where you want the folds to fall, and mark those points on the fabric. Then go along the strip, folding and pinning where you marked it. Attach the pleat to the material and pin in place. For heavy material, I recommend topstitching the pleat rather than treating it like an ordinary seam. Just as for a ruffle, don’t press the seam open; press it away from the pleat.

Other sorts of decorative trim (such as ribbon, braid, and lace) are usually topstitched to the outside of the garment or tacked invisibly to the underside of hems, necklines, and sleeves, where they can peek out.

Clothing Design

The real thrill in sewing is inventing things, and then wearing them. Sewing from store-bought patterns is useful as an exercise, but such clothes will neither fit like custom clothing nor reveal the full powers of your imagination.

It’s true that store-bought patterns assume you will modify them to fit your figure, but fitting can be pretty confusing without some knowledge of how patterns are developed in the first place. And if you neglect fitting, you’re left with clothes that either hang sack-style or rely on elastic for their structure (and all the bunching that goes along with elastic). Sewing patterns are particularly prone to these faults because the designers know you can’t try on a sewing project before you’ve actually gone to the trouble of making it, so they err on the side of excess material.

I’m going to focus here on dress design simply because designing a dress involves most of the problems you’ll face when designing things generally. The bodice of the dress is particularly troublesome. You know how hard it is to make a flat map of a round earth? Ha. Spheres are easy. They are so predictable. Mapping a body is the real challenge—creating a three-dimensional surface with two-dimensional cloth. The neat linear progression of clothing sizes obscures the great variety of body shapes and isn’t actually either neat or linear when it comes to women’s clothing.

You have a distinct advantage over manufacturers in that you need concern yourself with only your own body (or whomever you’re making clothing for), and not averages of millions of people or fashion model ideals.

As with many things, the key to design success is starting with a draft. If you will be making a lot of clothes, it’s worth the trouble to make yourself a sloper. A sloper is basically a dress model laid flat—it’s the clothing-pattern version of you, a second skin made of fabric. You can use it to modify any pattern you have found and modify it to generate patterns that will be sure to fit right.

To make a sloper, start with a generic fitted bodice pattern approximately your size. Cut it out in a cheap but tightly woven cloth like muslin (or a reasonably firm old sheet), stitch it together, and try it on. Adjust the fit with pins, tucking it along the seams or preexisting dart lines or marking places where it needs to be let out, until you have a close fit, without pulling, bunching, or sagging. It should fit closer than most clothes—when you go to make a clothing pattern from it, you’ll add the necessary ease to make it comfortable. Take it off and stitch it along the new lines. Try it on again and iterate the process until you have a perfect fit. Mark the final seam and dart lines, take the garment apart, and lay it out flat. Cut the pattern along the marked lines (don’t worry about seam allowances now), and then trace each piece onto cardboard. This collection of cardboard pattern pieces is a two-dimensional representation of your body and is incredibly useful.

Have a new pattern you want to try? Lay the sloper pieces over it to see what adjustments you’ll need to make. The style of the dress will dictate how much ease to allow for, but in the horizontal dimension, the difference between the sloper and the pattern should be consistent. Don’t worry if the pattern’s darts don’t fall in the same location as the sloper’s—just be sure that the cumulative width of the darts matches.

To use the sloper to create a pattern, trace it onto paper, add ease and seam allowances, and whatever peculiar design features you have in mind. Darts can move around, so long as they point at generally the same spot and their total width remains constant. Or darts can turn into princess seams, tucks, pleats, or gathers.

If you just want to jump into a particular project, you can combine the fitting stage and the design into one project: the muslin. A muslin is a cheap mockup of a pattern, made to be brutally altered and experimented with. In order to get an accurate representation of fit and drape, it’s important that you use material fairly similar to what you’ll use in your final product, in terms of weight and stretch.

Now, for your pattern. You’ve filled sketchbooks with ideas for how this dress should look. You want it to have a wide, fitted waistband, say, and princess seams, and a slightly rounded square neckline. Or maybe you want mega-puffy sleeves and a dropped V-shaped waistline. Maybe you want a dress just like the moth-eaten purple one you found in an abandoned house. Between articles of clothing that you already own, and patterns you can browse in a sewing store, and the vast Internet, you can figure out the general shape and size of the pattern pieces you’ll need. As for the specifics, some of them are in your head, and some of them will show up only after the tenth iteration of the fitting process. This is why you make a muslin!

Bodice

If you don’t have a sloper ready at hand, I recommend scouring the thrift store for a dress with a bodice similar to the one you have in mind, that fits you fairly well, and that you don’t love for its own sake. Avoid knits, or anything with stretch (unless your finished dress will be stretchy, in which case you’d better find something with the same amount and type of stretch as your finished dress). You want a firm, tight weave to get an accurate template. The skirt and sleeves don’t matter so much, as you can easily swap them out for other designs.

I’m very much in favor of taking things apart to find out how they’re made. You can certainly trace pattern pieces from preexisting clothing, but it’s quite tricky to get an accurate tracing without taking the dress apart. Especially if there’s a lot of tailoring in the form of darts, pleats, tucks, and gathers (and if there isn’t—what’s the point? Go trace a flour sack).

Pick out the stitches and rip the seams of this dress to give yourself a quick starting point for your pattern. How much seam allowance do the pieces have? It’s most accurate to ignore the manufacturer’s seam allowances—many manufactured seams are serged, which means your seam allowance will need to be greater than theirs. In addition, some seams may be worn and fraying. It’s easiest to just fold the seam allowance out of the way or cut it off (if you’re not interested in sewing the garment back together). You’ll add your own seam allowance later. In any case, it’s a good idea to iron the fabric pieces smooth before tracing them. Lay them out on paper, taking care not to stretch or distort them, and trace them carefully. Then draw a line on the pattern pieces to indicate the grain of the cloth and mark any useful points of reference (buttons, dart lines, etc.).

The general shape of a bodice pattern.

Make your creative modifications and add seam allowances to the traced paper pieces, and then lay them out on your muslin, lining them up with the grain of the fabric, of course. Pin them securely; cut them out; stitch any darts, tucks, or gathers; and start stitching the pieces together. You can deal with sleeves and skirts later; for now you just want the bodice to fit right. When you try it on, be aware that the weight of the skirt will certainly affect how the bodice hangs, but you’ll have to use your imagination for now. Also, any raw edges at the neckline, hem, or other openings will stretch more than they will in the finished product. It wouldn’t hurt to run a line of stitching around these areas so they have less give. Pay attention to the fit of the armholes, too; other adjustments you make can change the size of the openings.

The fitting and adjusting process requires a lot of patience. Be sure that every time you modify the muslin, you make the corresponding modification to your paper patterns.

Note: You can always use the finished, adjusted muslin as the lining for your dress, provided you sew it inside out. This will only matter if there are asymmetrical pieces (like for buttons, where one side of the dress overlaps the other).

A WORD ON SLEEVES

Once the bodice is complete, you can attach your sleeves. If you have never attached sleeves before, take a deep breath and get plenty of pins handy. When adjusting the bodice, did you make any changes that would affect the size of the arm opening? the arm opening changes whenever you take in or let out the side seams, shoulder seams, princess seams, or darts that open onto the armhole (aka armscye).

Presumably, if the bodice is done, your arm still fits comfortably through the armhole, but now you’ll need to adjust the sleeve pattern. With a cloth measuring tape, carefully measure around the armholes in the finished bodice. Next, carefully measure your existing sleeve pattern between the seam allowances, making sure to bend it precisely around all the curves (use pins to prop it in place as you go). Puffy sleeves will always be significantly larger than the opening, but all sleeves should be at least 1⁄2 to 1 inch larger; this is the ease allowance.

First, mark the top point of the sleeve curve. Stitch the sleeve to itself lengthwise and hem it. To attach the sleeve, turn the bodice and the sleeve inside out, and slide the sleeve into the armscye. Pin the sleeve seam to the underarm seam, and the marked spot to the shoulder seam. Pin the rest of the sleeve carefully. Since the sleeve fabric is longer than the sleeve opening, you’ll have to ease them together, distributing the excess fabric carefully. If the sleeve is puffy, keep most of the excess fabric to the top of the sleeve (and a very puffy sleeve will warrant a preliminary basting stitch to gather it before attachment). For a smooth sleeve, distribute the excess evenly so no actual folds form. You’ll be pinning at least every 1⁄2 inch.

Stitch in place with your usual seam allowance. Don’t press the seam open; press the seam together away from the bodice.

Skirts

You can fairly easily conjure a simple skirt pattern from thin air, after carefully examining some samples. Pencil and A-line skirts have roughly rectangular and triangular gores, respectively. Gathered skirts can be made of large rectangular (or triangular) pieces, but they generally require fabric be one-and-a-half to three times the desired finished width.

PENCIL SKIRT

Measure your waist at the point the skirt will hang from (the bottom of the bodice, if it’s part of a dress). Measure the widest part of your hips, as this will determine the width of the panels you need to cut. Then decide how long you’d like the skirt to be and how many gores you’d like (two or four are common). Pencil skirt panels are close to rectangular. The difference between the hip and waist measurements will tell you how many inches you’ll need to remove from the top of the rectangle, either with darts, gathers, or just trimming the corners of the rectangle. You’ll probably need more of this sort of tailoring in the back than in the front of the skirt.

A generic pencil skirt pattern.

A-LINE SKIRT

The pattern pieces for an A-line skirt look like pieces of pie with a curved bite taken from the point. When the pieces are assembled, the “bites” line up to form the circular opening for your waist. The difference between the top and bottom width of the gores will determine how full the skirt is. If the gores are fairly straight, you may want to use some darts as well. An A-line skirt can have as few as two gores (front and back), or dozens.

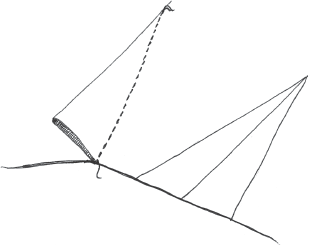

Drafting a pattern piece for an A-line skirt. R is the radius of a circle with the same circumference as your waist. L is the length of the skirt.

The trickiest part will be putting the right curve on the bottom edge of each piece, so that when the pieces are all assembled they form one smooth, even edge, instead of scallops or points. One way to do this is to think of your skirt pieces laid out flat as a circle or semicircle. A very full skirt will form a full circle; a narrow A-line skirt might form a quarter circle (and will probably require darts). Decide what fraction of the circle your skirt forms (that is, a half, a third, or three-quarters of a circle), and call that fraction f. Call your waist measurement w. Then each of your pattern pieces will be approximately the illustrated shape, with r being the waist radius. (Note: If you are attaching the skirt to a dress, you need to measure the bottom of the dress’s bodice, not your actual waist.)

r = w ÷ (f × 2π)

This formula makes it easy to draft the pattern pieces. Lay out a large piece of paper (or several firmly taped together), draw the straight edges of your gore, then use a yardstick to mark several points that are r inches away from the corner point of the slice. Draw the arc that connects these points to form the waistline of this pattern piece. Then, much farther out, mark many points that are r + l inches from the corner point of the slice, where l is the desired length of the skirt. Connect these points with an arc, and you will have the bottom edge of your pattern piece. Add seam allowances and room for zippers or buttons, and you will be ready to make the muslin mockup.

Of course, in spite of all these exact measurements, both cloth and the human body are soft and flexible. A-line skirts will necessarily have areas that are hanging on the bias of the fabric, which means they will stretch more than areas that are hanging with the grain. Furthermore, if you have a posterior of any sort, the back of the skirt will need to be slightly longer for the hem to be level. These variations will be most noticeable on shorter, narrower skirts. In any case, the hem is pretty much the last part of a dress or skirt to be finished, and the key here is to build in some excess and mark the final hem when the dress is actually on you.