The settlement of Triparadeisus was only a semicolon in the Diadochi Wars, hardly bringing a pause to the ongoing saga of venomous embattlement. Antipater soon returned to Pella, leaving Antigonus at the helm in Asia. He, in charge at last, began to show the qualities of decisiveness, speed, imagination and determination that would define his career. But, for all his success against Eumenes, against Alcetas and in reclaiming the Aegean provinces from hostile satraps, it was only to be a prelude.

Everything draws the attention towards the campaigns of 317/316 BC; we have comprehensive details of the manoeuvring and the epic clashes that characterize this time, which is rarely true of other years. The thinking of the combatants is understandable; the very battle plans themselves are available, as is seldom the case in any period before modern times. The reason is that we have a real spy on the ground. Hieronymus of Cardia, who provides the main source for Diodorus at this time, was in a unique position to understand and report on events and probably would even have had access to recorded orders of battle. He was present at the highest levels for not just one but for both sides. In a long life he first spent years in the entourage of Eumenes and, on his demise, became a long-term officer in the service of the great Antigonids, father and son; and he was still active at the court of Antigonus Gonatus. Indeed it is possible to read an agenda into his work that while critical of Antigonus and Demetrius, he buffed with relish the reputation of the grandson in a period when that king was trying to establish a south Balkan hegemony. This remarkable chronicler who we are so dependent on (channelled through Diodorus) is even claimed to have lived to 104 years of age.1

The one great drawback in understanding these events is that the fighting took place in Susiane, Persia and the heart of Iran, not places familiar to those who described the course of events. Many informants may have been to these places with Alexander, or after, but they did not know the terrain, as they would have the country around Pella, Vergina, Thermopylae or the Gulf of Corinth. So they are much less able to pinpoint where things occurred than they would have been in the familiar terrain of Greece, or even Western Anatolia. And this ignorance from the start is compounded by the fact that for many generations little in the way of archaeology or even historical geographical exploration has been possible in an area wracked by war and foreign invasion. People do try and make guesses where the events were placed but it is all conjecture of the least convincing kind. How can a comment in the sources about where a ridge, a river or a salt plain were really enable somebody to pinpoint the great battlefields of this war? All that is possible is to suggest the general region where the specific conflicts were played out. Yet, the drama of the two greatest of the commanders to emerge in the decade after Alexander’s death slugging it out with the most formidable armies fielded by any of the Diadochi none the less makes it compelling.

Antigonus, in late 319 BC, looked to many unstoppable, but that was only a local perspective. While he pushed all over before him in Pisidia, then Hellespontine Phrygia and Lydia, a brew of troubles was being concocted for him by a formidable trio. Polyperchon, as guardian of the kings, egged on by Olympias, mother of Alexander, had mobilized that temporarily dormant genius, Eumenes, to get back in the ring. Credibility, legitimacy and the money it opened up meant this brilliant man had been able to create a force round the veteran Silver Shields that he would wield with lambent intelligence in the couple of years to come. He had retreated into the heart of Asia, as Antigonus harried him again, but it was not just to get away but also in the hope of finding friends there. Seleucus, at Babylon, had not been responsive but as he approached the Iranian satrapies, the rulers there, already united against their problematic neighbour, Pithon, satrap of Media, had joined him in Susiane.

As campaigning opened in 317 BC, Eumenes had both his own army and the combined forces of the satraps that consisted of 18,700 foot and 4,600 horse. But the group that had come together so recently was not without its fissures. The personal dynamic was fraught with individual rivalries as, apart from Peucestas, there were a number of formidable leaders present. The satraps of Carmania, Arachosia, Aria and Drangiana had all contributed troops and Eudamus had come from India, where the Alexandrine settlement was crumbling, with a considerable army that included 120 elephants. Tension amongst these egos was inevitable, as all of them could boast years of experience in the army of Alexander and their very survival in positions of great importance, since his demise, labelled them as veterans of considerable stature and ability. They knew Antigonus had disposed of most of their colleagues around the Aegean and would be bringing a huge army with him. He had followed Eumenes across Mesopotamia, but to reach them there were still natural obstacles in the way. But, soon enough news arrived that the intruders had thrown a pontoon bridge over the Tigris and their army was across the last great natural barrier between them and Susa. Eumenes and the satraps, despite rivalry over command, had come to a modus vivendi that, at least, allowed key decisions to be made. The first of these was premised on the fact that they were outnumbered and so they decided to decamp.

As they struck their tents and marched out south, the coalition leaders were on the look out for a place that they could hope to defend with confidence. They thought they had found it at the Pasitigris River, a waterway which Alexander himself had cruised down to the sea in 324 BC, shortly after the Susa weddings. This, they decided would provide a front line that any attacker would find difficult to pierce with an active defender ensconced on the other side. The great drawback was the extent of the shield which they sought to utilize; it was bound to try the abilities of any defender to watch over its whole length effectively.

Pickets were posted along the bank, from the source of the river to the sea, to ensure the enemy could not slip by unnoticed. To cover this vast front was no small matter. In fact, it required Peucestas to call on the resources of the province he had controlled since before Alexander’s death. Officers were despatched back to his adjacent satrapy to raise 10,000 more Persian bowmen. And, there is little question this display of local might was not intended to be lost on both the leaders and the soldiers of the coalition. This was not the first time Peucestas had shown what a cornucopia of military resources he controlled. In 323 BC, he had provided Alexander with 20,000 soldiers who it had been intended to incorporate in the body of the Macedonian phalanx. It was planned that each file of the new combined units would consist of four Macedonian pikemen and twelve Iranian troops using lighter local equipment that would provide the new regiments with missile-hitting power. This experiment was not destined to last long; as soon as Alexander died it was shelved, never to be resuscitated.

Antigonus, meanwhile, had joined the Royal Road to Susa, after crossing the Tigris. Days of marching in the late June heat had meant very real attrition for Antigonus’ men. Trekking when the sun was down helped a little but still the temperatures were almost more than the body could bear and, on top of this, the road to the Pasitigris was far from clear. Before reaching this watercourse, the invaders found themselves confronted by a considerable tributary called the Coprates.

Eumenes had been keeping Antigonus under surveillance all the way and scouts in forward positions kept him well informed on his movements. At the Coprates, Antigonus found himself in some difficulties, as his officers could not find sufficient boats to transport the army across the river. He immediately began ferrying what men he could across the river to build, as quickly as possible, a defended camp that could hold the position while the rest got across. When this was reported, Eumenes decided on a surprise attack. Covering the 9 miles from his encampment to the Coprates at great speed, he and a small force of 4,000 foot and 1,300 horse fell on the Antigonids. About 9,000 men had crossed when Eumenes launched his attack but 6,000 had dispersed to forage. Whether this was indiscipline, or even if sanctioned by the high command, it was very foolish when such an active commander as Eumenes was not far away. The remainder of the soldiers had begun to dig a defensive ditch and to construct a palisaded bridgehead, but the stockade was incomplete and the defenders had their backs to the river, with no room to manoeuvre when the enemy arrived. The Antigonids did not have time to put down their tools, pick up their arms and get into proper fighting formations. As all they could do was defend themselves as best they could against superior numbers, this was not likely to be successful. The faint hearted soon started to run for the boats and what order they had struggled into began to crumble. Soon, all organized resistance ceased and the only thought that Antigonus’ men had was to get back over the river to the protection of the main army. The old man looked on helplessly as the debacle was completed when the very numbers of terrified fugitives capsized the boats and dumped his soldiers into the rushing waters, which carried most away to their death. The men who had gone off to forage now returned in dribs and drabs and, unable to put up any defence at all, were killed or captured. Eumenes was outnumbered and his command structure fractured, but he was an extraordinary talent and this coup had cost Antigonus as many as 8,000 casualties including 4,000 prisoners.

The Antigonid army was hot, frustrated and confused; a weaker foe was keeping them at arm’s length, causing great loss, and there seemed no likelihood of the decisive action that Antigonus craved. To try and winkle the confederates out of their position by force seemed futile and another strategy needed to be tried. He decided that to revitalize the army’s sagging spirits, progress and success were needed. The lands of the upper satrapies were relatively unprotected, with their rulers and their best troops away with Eumenes. This, potentially a rich source of plunder, was attractive because it would both encourage his followers and it would make the generals with Eumenes squeal and insist he leave his hidey-hole to return to protect their holdings. Antigonus, decided on this course of action, set off north to Ecbatana, formerly the Persian king’s summer capital in the hills of Media, where his men could also escape the roasting climate of Susiane.

Antigonus, in putting his plan into practice, showed less intelligence than in preparing it. Displaying an impatience that on several occasions would lead him into trouble, he determined to march directly north over the mountains instead of the army taking the longer but much easier route via the royal road, up the Tigris valley, before branching right through the Zagros range at the Median Gates. This way led through the territory of the Cossaeans. They were a hardy, aggressive and ‘uncivilized’ tribe who apparently still lived in caves and subsisted on acorns, mushrooms and wild game. But, if they lacked the amenities of life, their knowledge of the mountains made them formidable opposition on their own land. The Persian kings had sensibly left them untamed and paid tribute if they wished to use the routes through their territory. However, Alexander had not been prepared to suffer their presumptuous independence and campaigned against them. The Cossaeans could not have chosen a worse moment to challenge him, as he was suffering from massive bereavement at the death of Hephaistion, his chiliarch and favourite. Alexander vented his grief; harrying them for forty days through their glens and forests, massacring or deporting those he found. Almost seven years had passed since this humiliation and many had forgotten this unpleasant taste of Macedonian might, so they again demanded tribute from Antigonus. He compounded his already dangerous decision to march this way by refusing to pay. Pithon, more familiar with local customs, advised against such arrogance but Antigonus would not be swayed. The Cossaeans decided to take their tribute by force of arms.

Realizing he would have to fight, the old general ordered his line in a competent manner. His missile men, peltasts, bowmen and slingers were divided into two parts; one to go ahead and occupy the main passes and the other to be distributed amongst the whole army and give it protection. In charge of the first detachment was Nearchus, Alexander’s favourite admiral and a man who had disappeared from view since Babylon, where he had tried to foist Alexander’s illegitimate son, Heracles, on the Macedonian assembly.2 Antigonus marched with the phalanx in the middle of the army, while Pithon brought up the rear with selected light-armed troops. All these preparations could not ensure protection from the fierce Cossaeans, especially as Antigonus had a massive army with camp followers and baggage, particularly vulnerable, as it snaked its way along the seemingly never-ending passes. Nearchus faced strong opposition and lost many men while the main body found itself under pressure all along the route as the Cossaeans occupied the high ground and rained missiles down on the Antigonids with impunity. The horses and elephants suffered particularly severely and many did not survive.

As for the troops led by Antigonus, whenever they came to those difficult passes, they fell into dangers in which no aid could reach them. For the natives, who were familiar with the region and had occupied the heights in advance, kept rolling great rocks in quick succession upon the marching troops.3

After a harrowing eight days, they finally managed to reach the safety of Media. Though an ordeal of shorter duration, this episode is very reminiscent of the march of Xenophon’s 10,000 and after their travails Antigonus’ men must have greeted the end of the Cossaean hills with as much relief as those earlier Greeks did the Black Sea coast. Morale, though, had again been heavily shaken and Antigonus must have rued his refusal to pay tribute. For once, he should have listened to Pithon.

In Media, Antigonus’ first concern was to revive the flagging spirits of his men who, in the last month and a half, had suffered much from both the hands of man and nature. They were rested and fresh supplies brought in, while he personally visited as many troops as he could to convince them that the setbacks were only temporary. Pithon, back in his old province, was sent to get reinforcements. This he did with some élan, bringing back 2,000 horsemen and an additional 1,000 mounts as well as numerous pack animals and 500 talents from the eastern treasury at Ecbatana. By giving the horses to those who had so recently lost their own and distributing the pack animals as presents, Antigonus did much to restore spirits. The Antigonids in Media were also much relieved when news arrived that the ploy to draw their enemy out from behind his entrenched position had worked as well as could have been expected. The arguments in the coalition command tent had been bitter and protracted, but eventually things had fallen out as Antigonus had hoped it might.

The Cardian and the officers who had come with him saw an opportunity with Antigonus far to the north to retrace their steps back to Babylonia and the Levant. This open road to the west would put them, with a mighty host, at the centres of power in Syria, Phoenicia, and Cilicia and not far from the great cities of the Aegean. But the satraps were not prepared to leave their provinces open to depredations by the invader. A reluctant Eumenes had to fall in with men whom he knew, at bottom, that he absolutely needed. So, the mix of Macedonians, Greeks, Iranians and Indians who comprised the coalition army moved away towards Persepolis, the capital of the Persian lands, where Peucestas had been the ruler for almost ten years. They took it easy, no foolish escapades against hardy locals for them; in fact, they went through country so bounteous it allowed them to flesh out both their numbers under arms and their quartermasters’ stores.

Peucestas had, from the beginning, been intriguing to be appointed commander in chief of the allied army and took advantage of their presence in his own province. He laid on ostentatious entertainment:

With the company of those participating he filled four circles, one within the other, with the largest enclosing the others. The circuit of the outer ring was of ten stades (approximately 6,000 feet) and was filled with the mercenaries and the mass of the allies; the circuit of the second was of eight stades and in it were the Macedonian Silver Shields and those of the Companions who had fought under Alexander; the circuit of the next was of four stades and its area was filled with the reclining men – the commanders of lower rank, the friends and generals who were unassigned, and the cavalry; lastly in the inner circle with a perimeter of two stades each of the generals and hipparchs and also each of the Persians who was most highly honoured occupied his own couch. In the middle of these there were the altars for the gods and for Alexander and Philip. The couches were formed of heaps of leaves covered by hangings and rugs of every kind, since Persia furnished in plenty everything needed for luxury and enjoyment; and the circles were sufficiently separated from each other so that the banqueters should not be crowded and that all the provisions should be near at hand.4

Competition for command seemed to be really heating up and Eumenes, deep in the heart of Peucestas’ satrapy, was becoming very concerned. He responded with both carrot and stick. First, he circulated a forged letter that peddled it that Olympias had gained complete control in Macedonia, had slain Cassander and sent Polyperchon into Anatolia. Indeed, it was claimed he had reached Cappadocia with an army that included elephants. With this making an impression (it looked to auger very well for the campaign now the Cardian was to be reinforced) he also threatened a slippery ally with dismissal and death.

This was Sibyrtius, satrap of Arachosia, a close friend of Peucestas and it is not difficult to see against whom Eumenes was aiming. In fact, this episode is a little unclear as Diodorus claims he was close to being tried by the assembly, at the behest of Eumenes, and only escaped death by flight. Yet, soon after, he is recorded as still in situ in his satrapy, though it maybe he fled back and found his old government loyal and stayed there until the outcome of the contest between Antigonus and Eumenes became clear. Finally, to bind his iffy friends even closer, the Cardian borrowed 400 talents from the allied satraps, turning them ‘into most faithful guards of his person and partners in the contest’.5

The enemy was now near at hand, for Antigonus had broken camp in Media and set out for Persia. Eumenes must have been confident in the arrangements he had just made – that hindsight shows us were to prove very rickety indeed – as he moved his army towards his enemy clearly now prepared for a fight. Yet, he was still thinking about hearts and minds and, though not quite able to compete with Peucestas’ munificence, he still threw a party for the army at which everybody indulged in the binge drinking that Macedonians were famous for. Eumenes, it seems, was first at the front of the wine queue, as he was so hung over and incapacitated that for several days the army was reduced to waiting for its commander to recover.6 Indeed, even when they moved off, he was reduced to following his men in a litter with temporary command exercized by Antigenes and Peucestas. At least here was a safety valve, as these two hated each other so much that they would be unlikely to join forces to depose Eumenes.

The two sides, after many months of chasing each other, finally came face to face. Yet, even then the final denouement was not at hand. For both armies had drawn up on either side of a river in a ravine, making a battle impossible. For five days they swapped insults, skirmished and plundered the countryside; a hiatus in which an impatient Antigonus sent agents over to try and subvert the satraps. Strangely enough, their efforts seem almost open as Eumenes knew of their presence and even protected them from his followers who became enraged by their importuning at what Diodorus claims as an army assembly. This parallels the claim that Ptolemy spoke before Perdiccas’ army prior to the invasion of Egypt but is perhaps slightly more plausible. In this case, Eumenes did not have the complete authority that Perdiccas had on the previous occasion, and, perhaps for the sake of unity, had to let the satraps hear what Antigonus had to say.

The coalition leaders would not hear of Antigonus’ terms and by now his army had become desperately short of forage and was forced to move. Their destination was the plains of Gabene, a three-day march away, where there were ample supplies. However, dissatisfaction in the Antigonid ranks caused some desertions and, by this means, Eumenes got wind of their plans. Eumenes, showing the skills that made him probably the greatest general of all the Diadochi, proceeded to outwit Antigonus. He correctly guessed where Antigonus was heading and determined to get there before him and take up the best position. To do this, he needed a breathing space so he sent some soldiers over to Antigonus posing as deserters. They put it out that Eumenes was preparing a night attack, information that Antigonus readily believed. Eumenes, meanwhile, secretly sent his baggage on ahead and stealthily withdrew towards Gabene. After some time, Antigonus realized he had been duped and reacted swiftly. Leaving the bulk of the army under Pithon, he rode out at top speed with his cavalry. By dawn he had managed to overtake the enemy’s rearguard and took up position on a favourable ridge. Giving the false impression that he had more troops than was the case, Antigonus forced Eumenes to turn and draw up his forces in battle formation. A manoeuvre that inevitably took up much time and allowed Pithon to arrive and now from high ground Antigonus could at last force a fight on his enemy.

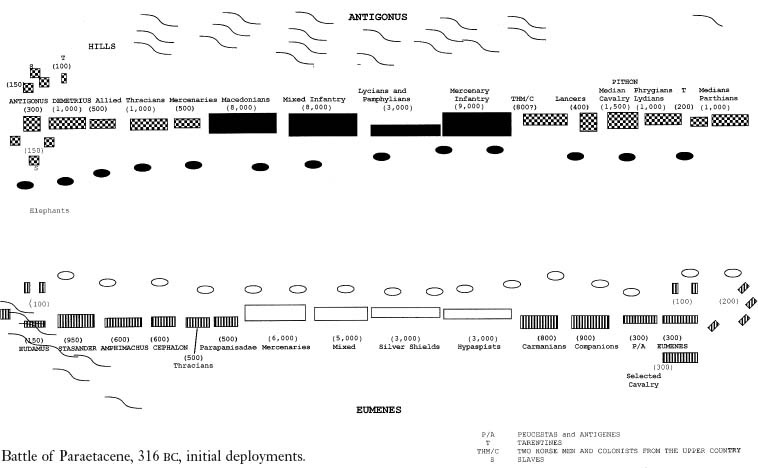

Thus began the first of the two epic battles that are the centrepiece of this campaign and, it could be argued, the whole Diadochi era. Diodorus states Antigonus fielded 28,000 infantry (in reality this number is just those in the phalanx and does not include many thousands of light troops), 8,500 horse and 65 elephants. On the left wing, under the treacherous but competent Pithon, were drawn up the lightest of his horsemen and here the tactical intention could not be clearer, they ‘were to avoid a frontal action but maintain a battle of wheeling tactics’.7 These were the classic manoeuvres of steppe peoples that achieved so much for the Scythians, Sakae and Parthians, both before this and in generations to come. They were to use these tactics to occupy the strong right wing of Eumenes that Antigonus could see deployed below him from the heights. There were 1,000 Medes and Parthians described as lancers or horse archers. Then, according to Diodorus, came 2,200 Tarentines who were brigaded with them, ‘men selected for their skill in ambushing’; an interesting new type of soldier who are given their first mention in this war; skirmishers who carried javelins and a small shield.8 The association with the Italian city of Tarentum is real enough: coins from there show just such soldiers. In the cosmopolitan world that had seen Alexander’s uncle fighting in southern Italy, it demonstrates the cross-fertilization of military techniques. The actual origin of these Tarentines is obscure; they are described as coming up from the sea but this is probably to distinguish them from the men who had joined Antigonus in Mesopotamia and Iran. A problem here is that this is a far larger group than you would expect from a new specialist troop type that had travelled up from the Mediterranean, even if not from Italy itself, and perhaps it is best to lose a nought from this estimate. Particularly as when Tarentines are again mentioned, whether when they ambush Eumenes’ elephants or a few years later at the Battle of Gaza in 312 BC it is usually in numbers of a couple of hundred or so, never even close to the 2,200 recorded here. To reduce the number of Tarentines would also help solve the arithmetical dilemma that Diodorus poses when he states Antigonus had 8,500 cavalry but, in fact, all the separate units mentioned add up to 10,600.

After the Tarentines came 1,000 Phrygians and Lydians, gentry from West Anatolia with long association with Antigonus. Then 1,500 horse with Pithon, who we have no evidence about, but common sense suggests Pithon would have had with him good horse from his satrapy of Media. The last units on the left flank were 400 lancers under a Lysanias. Being on the left, these were probably light lancers rather than heavies who confusingly can also sometimes be designated by the same name. The rest of the left wing was made up of the ‘two horse men’ and 800 colonists from the upper satrapies. We know nothing of either of these regiments though presumably the former actually brought an extra horse to battle. Most cavalrymen had spare mounts; Alexander, famously, would only saddle up Bucephalus, his favourite warhorse, just before battle, using another one to get him to the field of combat. But, to get such a designation these men must have actually brought the spare mount into the line of battle, though it is not clear what great advantage this would give. If it meant they had a fresh steed immediately available, it also meant they needed to use one of their hands to hold the halter of the led horse which must have considerably impaired their fighting ability. What is interesting is that there are no figures given, so perhaps there were only a few of them and they had a specialist role. Last in the left wing were those 800 colonists already mentioned and all we can surmise is that, as colonists in the upper satrapies, they were most likely European or Anatolian horse who could have been settled by Alexander, or any others who had passed through the east in the years since his death. But, as the whole of the left is specified as being required to skirmish rather than charge straight home against the enemy, it is reasonable to suggest they again were light horse with either javelin or lance and with no armour except possibly a helmet. There was something around 7,000 all told on this wing if the high figure of Tarentines is accepted, but about 5,000 if the lower is used.

The 28,000 infantry mentioned are all attested in the phalanx. On the left 9,000 mercenaries; then 3,000 Lycians and Pamphylians (Anatolians who are perhaps specifically designated thus because they were old soldiers of Antigonus); more than 8,000 mixed troops in Macedonian equipment and then the nearly 8,000 real Macedonians who had come courtesy of Antipater at the start of the war. This indicates that 16,000 men in the phalanx carried sarissa and pelte as opposed to the classical panoply of aspis and shorter spear carried by the rest. What this leaves out is many thousands of light-armed troops that must have been fielded. Eumenes, for his part, had almost as many light troops as he had soldiers in his phalanx but he would have certainly had a higher ratio than Antigonus as many of his allies brought large numbers with them from satrapies that specialized in producing this kind of missile-armed warrior. Yet still Antigonus must have had many thousands; he would have needed at least 3,000 just to provide guards for his 65 elephants.

The horsemen on the right wing were intended by Antigonus as the battle winners, the clunking fist to compliment the defensive jabbing of Pithon. Nearest the infantry came 500 mercenaries, some may have been the Greek light mercenary horse who survived the massacre of their fellows in Sogdia while Alexander still lived. Next came 1,000 Thracians, who may have been light cavalry of the type Alexander brought with him from Europe or heavier armoured warriors typical of the aristocratic horse of that region. Then 500 who are described as from the allies, perhaps the cavalry from the allied Greek horse who stayed on while their units were demobilized at Ecbatana, after Darius had been defeated. How they were equipped is unknown but it is probable that most, if not all, were heavies, wearing body armour and welding the long cornel wood spear. The Companions, 1,000 strong, came next under Demetrius. He is on this occasion mentioned as specifically in charge of just these heroes as he was ‘now about to fight in company with his father for the first time’, while at the next battle he would be attested as in command of the whole right wing of the army.9 And in the place of honour at the very edge on the right stood the old marshal himself, with his personal guard (agema) of 300. Placed in advance of them were 100 Tarentines and three troops of what are described as his slaves; we have no idea who they were but they would not have been servile retainers but brave and tried warriors. Their position as an advance guard in front of Antigonus’ own agema suggests they, too, would be light horse deployed, no doubt, to clear the way of enemy skirmishers, enabling Antigonus to fling his heavy men down the throat of his opponent. This made 3,700 men in the whole wing, so in numbers they were considerably weaker than the left wing but in quality they included the very best. In front of this splendid assembly of mainly heavy horse, thirty elephants were drawn up, with most of the rest in front of the infantry phalanx and just an unspecified few guarding Pithon’s front on the left. Antigonus led this awesome array down the mountain ridge they stood on towards the coalition army waiting for him.

Eumenes fielded 35,000 foot, 6,100 cavalry and 114 elephants. Much was analogous in his array to that of his counterpart and here, too, the allied left was intended to hold back and soak up the enemies’ blows rather than deal the coup de grâce. In command was Eudamus, who had brought the crucial elephants, fresh from the Indus valley. As well, there were fifty mounted light horse lancers posted as an advance guard at the base of the hill that the rest of Eudamus’ bodyguard was deployed on. After these men on the hill, to anchor the line came Stasander with 950 light horse from Aria and Drangiana, after him came Amphimachus, satrap of Mesopotamia, with 600 horsemen. This man may have been the half brother of Philip Arrhidaeus but what sort of cavalry he commanded we do not know.10 Then came 600 Arachosian cavalry, no longer under Sibyrtius who had fled, but led by Cephalon, 500 Parapamisadae from the Hindu Kush and again most probably light horse like their comrades from the Indus. Approximately 500 Thracians from the upper country, troops planted in townships in the upper satrapies at some time since Alexander passed by, were on the right side of the left flank and thus adjacent to the infantry phalanx. Forty-five elephants stood in front of them with bowmen and slingers to protect the great beasts. Most of the horse on this left wing were light horse, unarmoured javelin men or lancers, best for scouting and skirmishing. The troops from Mesopotamia may have been a heavier type and the same is true of the Thracians, though being arrayed with their lighter comrades might suggest they too were of this type. But, it is not impossible that some heavy armoured men, fit for close combat, were placed there to stiffen the whole left wing just as some would have been bodyguard troops, well armoured and fit for hand-to-hand fighting. Altogether they amounted to 3,400 horsemen.

In the centre came the phalanx, first 6,000 mercenaries and then 5,000 equipped like Macedonians ‘although they were of all races’.11 Next came more than 3,000 Silver Shields and then, more than 3,000 ‘from the hypaspists’ taking the place of honour on the right.12 So Eumenes fielded 11,000 sarissa-armed phalangites with the other 6,000 most probably classically-armed hoplites. Forty elephants stood arrayed in front of these spear and pikemen.

On the right of the phalanx were fielded most of the heavy cavalry Eumenes had at Paraetacene. First was Tlepolemus with 800 cavalry from Carmania, they came from the country east of Persia, itself, and probably produced warriors similarly armed to their cousins from that country. Then, 900 Companions, the heirs of Alexander’s own, and then 300 cavalry under Peucestas and Antigenes (who though recorded as commander of the Silver Shields, with Teutamus, did not lead them in battle but took his place with the other commanders with the cavalry) where these two presumably shared charge as they had shared command of the whole army when Eumenes was indisposed. They led the quality of Persia; many were moneyed enough to equip themselves and probably their mounts with protective armour. They and their Median comrades had, since just before Gaugamela when Darius refitted them, taken up the longer, stronger lance used by the Macedonian horse. About this group, Diodorus says ‘which contained three hundred horsemen arranged in a single unit.’13 This is not explained, but it may refer to a specially strengthened ile, a bodyguard such as Alexander’s royal squadron of the Companions that was just the same strength. If so, it was most probably Peucestas’ bodyguard.

After this was Eumenes on the far right wing leading a complex array of horsemen. First were 300 cavalry, again the figure suggests it was his personal agema of heavy cavalry, many were surely his loyal Cappadocians who are not placed elsewhere but would still have been with him. They would have been looking to continue receiving the benefits of following a victorious patron. We know the Cappadocians who fought for Darius sometimes wore a full covering of scale armour and with Eumenes’ elite it is likely they were as well protected. And they seem always to have wielded the long lance (xyston) with which the Persians and Medes had been re-equipped. As an advance guard in front of him were two lots of fifty mounted soldiers of what are called his ‘slaves’. They are otherwise not described, but as this is one of very few occasions any group of soldiers are so referred to in our period it suggests they were specially attached to their leader whether Eumenes or Antigonus. Furthermore, as slaves, in the sense usually used, were very seldom armed for battle (except in extremis when the very state was threatened with extinction as at the siege of Rhodes by Demetrius) it is likely they were some of his very best troops of light cavalry. Then, at an angle, guarding the wing were first 200 selected men in four groups and then another 300 described by Diodorus as ‘selected from all the cavalry commands for swiftness and strength’; presumably these were the best equipped and bravest men from all the satrapal retinues picked for the purpose, kept in reserve behind Eumenes’ wing.14 In front of all these were forty elephants15 with some of them positioned round and backwards to match the front of the flank guard.16

The two armies fought from afternoon to midnight. Pithon, on the Antigonid left, seems to have been unable to resist pressing where he had superiority in numbers and manoeuvrability. He pushed hard against the enemy elephants, worrying them with missiles; they were caught mesmerized, unmoving and taking considerable punishment. ‘They kept inflicting wounds with repeated flights of arrows suffering no harm themselves because of their mobility but causing great damage to the beasts, which because of their weight could neither pursue nor retire.’17 Pithon’s horse archers were performing as intended and Eumenes, with only heavy cavalry and elephants, seemed to have no answer. But, by taking the offensive, Pithon was to bring on unforeseen consequences. Understanding what the problem was, the Cardian determined to respond by bringing round the most mobile of the light horse from Eudamus’ wing to help counter Pithon’s attack. When this reinforcement arrived, having moved behind the infantry phalanx, Eumenes made a concentrated push using light horse, elephants and light infantry to attack Pithon’s men, who found the combination too strong and his remnants were pushed right back to the foothills behind the Antigonid battle line. If Antigonus had hoped his left wing would keep just to a holding role to occupy his enemies strongest wing he had been sorely disappointed.

While this was going on, in the centre the greater number of Antigonus’ infantry was countered by the fighting qualities of the Silver Shields, who won success after a stiff contest. Some of these veterans are claimed as 70 years old which seems excessive even in an era when many of the Successors, themselves, campaigned into old age. Whatever the real age of these Methuselahs, they it was, with sarissae levelled and shields locked, who with younger men in the taxis to their right and left, ensured the enemy infantry were defeated and pushed back towards the higher ground from which they had descended not long before.

But Antigonus now showed his quality, despite seeing his phalanx pushed back in defeat, if not in rout, and news reaching him that Pithon too had been overcome. He did not panic and felt no inclination to accept the outcome, withdraw back to the high country and attempt to rally what he could around his own undefeated forces. By his own swift action, he saved the army from destruction when he charged through the gap opened by the forward progress of Eumenes’ phalanx, following in pursuit of the Antigonid phalanx opposed to them. Through this breach Antigonus found himself behind the enemy phalanx and on the flank of the cavalry commanded by Eudamus, who, having sent many of his troops across to Eumenes’ wing, had remained immobile. This meant Antigonus was coming in from the flank; an attack from an unexpected quarter that proved a complete success. Many men were killed and the rest of Eudamus’ left wing cavalry driven away. Now Antigonus sent ‘out the swiftest of his mounted men and by means of them he assembled those of his soldiers who were fleeing and once more formed them into a line along the foothills.’18 This is confusing, but what must have occurred is that the thousands of his cavalry in the rear of the enemy battle line and the resultant danger they posed brought the advance of his opponents to a halt. Eumenes, thinking victory almost won, stood in the light of a full moon to harangue his generals into one last effort. Both armies had, by now, moved a long way from the original field of battle and reformed and faced each other. At only 400 feet apart, Diodorus seems to suggest the newly ordered armies began again to prepare to fight.19 But it was not to be, the hour having reached midnight and only the Cardian was prepared to fight on. His men would not countenance it with so much blood and effort already expended. So, reluctantly, the belligerent general withdrew and submitted to the insistence of his men that they get back to their baggage train which was now some miles in the rear of the main army.

Antigonus saw the enemy columns march away into the night with some relief; his army had missed being severely defeated by a hair’s breadth and only his own leadership in the crisis had averted disaster. His casualties amounted to around 4,000 foot and several score cavalry, many more than the few hundred dead the enemy had sustained. The consolation of camping his men on the battlefield, and technically being able to claim victory, did little to relieve the frustration that had been building since the setback on the Coprates River. The significance of setting up a victory trophy (usually of captured enemy panoplies hung on a convenient tree or frame, built if no trees were available), and of camping on the battlefield was very important. It meant that the victor could enjoy the fruits of looting the dead and also were able to most effectively try to identify their own dead and give them proper rites. And, just as Antigonus accomplished this, Eumenes also was forced into the other great ritual act of accepting defeat by sending to the enemy for permission to collect his own dead. This setting up of a victory trophy might help a little in retrieving the soldiers’ morale but the hollowness of the Antigonid claim to triumph was soon exposed when the orders were given to withdraw to Media, rather than pursue the enemy.

Yet still, what had occurred did highlight one great advantage Antigonus had over his opponent. He could command his men to stay put and camp on the battlefield whereas for Eumenes ‘there were many who disputed his right to command’; he had to cajole and persuade and at this time, in a way that presaged later developments, it was the baggage train that was the centre of many of his followers’ interests.20 However, Eumenes had much to be satisfied with. His own soldiers had fought remarkably well and his confederates had stayed loyal, despite the lack of a clear-cut victory and the withdrawal from the battlefield. It had been all hard campaigning since his men left Babylonia and, with the end of the year approaching, he led the army to the lush and unplundered land of Gabene to enjoy the winter in comfort. It had been in competing for control of this region that the Battle of Paraetacene had come about, leaving no doubt who had been the real victor.

Antigonus had been severely blooded and he wanted to put some distance between himself and his active enemy to gain time to recuperate, particularly as winter was coming on. By prevaricating as heralds talked about disposal of the bodies from both sides, he earned time to send off his baggage and wounded.21 He then forced-marched the rest of his men back to the city of Gamarga. Here, in Media, they could recuperate in a rich place with an administration well organized and loyal to his lieutenant, Pithon.

Eumenes had stayed where he was whilst the ritual of burial was accomplished and, at this time, Diodorus notes a particular event that indicates there was a strong Indian element in his army: ‘Ceteus, the general of the soldiers who had come from India’, had died in the battle and was cremated in the Indian fashion and both his wives, who were with the army, accompanied him into the flames.22 After the dead were given due rites, Eumenes did not pursue Antigonus but moved to enjoy the abundant resources of Gabene. So, as the year ended, the two forces rested several hundred miles apart.

Antigonus had shown qualities of grit, ambition and some tactical brilliance over the previous year but his performance had been far from flawless. He had received a bloody nose from Eumenes, shown bad decision making over the Cossaeans and had even been hoodwinked by his talented opponent on one occasion. But, whatever had gone before, it never affected his self-confidence or his determination to act. What was typical of him in a complex and difficult situation was his preparedness to bend the rules: to make war in the winter when custom and weather dictated a hiatus, to achieve what he could not the year before and bring the enemy to decisive battle.

Winter was just begun as Antigonus collected his men and animals from their camps in the hills and valleys of Media. He intended a surprise and though winter warfare had been pioneered by Philip II, to great effect, it was still the exception rather than the rule. He banked on Eumenes expecting him to remain under cover in a region where winter conditions could be fierce. It was twenty-five days’ march to Gabene by the regular road but there was another way. It had been learned, from local inhabitants, that Eumenes had distributed his units far and wide over a large area to make use of all available forage for the winter, and they would need several days to concentrate together again. By crossing the Dasht-e-Kavir Desert, the Antigonids could complete the journey to Gabene in just nine days. But it would be dangerous and uncomfortable across a grim waterless waste in the middle of the Iranian plateau, where hardly anything grew except a few shrubs that sustained the goats of the nomads who passed there on the way to better pasture. None the less, surprise was of the essence and many officers present knew that Alexander had traversed the fringes of this sterile region when he was chasing the fugitive Darius. But he had only taken a light-armed pursuit force across the edge of the desert while Antigonus intended to take the whole of his army through the heart of it.

This risky strategy had a particular advantage; the region was so inhospitable that it was not expected they would encounter any inhabitants who might alert the enemy. Great lengths were gone to in order to disguise their intention; word was spread that the preparations were for a move northwestwards to Armenia, a plausible enough plan after the defeats of the previous campaign. Ten days’ rations were distributed, leaving no room for error on the route and, in December 317 BC, the army set out. The forced march typified the qualities of Antigonus that would take him to the very pinnacle of success; a dash across harsh terrain at a time of year when custom and conditions demanded a cessation of fighting: all this to steal a march on an enemy who had recently handed out a bloody reverse that would have kept lesser men quiet for some time.

This Alexander-like enterprise did not meet with Alexander-like success. Eumenes was renowned for the quality of his intelligence system and on this occasion also had more than an element of good fortune. After five days marching across the desert with no night fires to warm them (Antigonus had strictly ordered this precaution against discovery), the soldiers could no longer bear the freezing temperatures (it has also been suggested the elephants particularly needed to be kept warm) and flagrantly began to light campfires whenever they stopped, day or night.23 Local people living near the edge of the desert saw the glow in the night sky. The speediest dromedaries were used to take the news to alert the Cardian general to the approaching threat. Peucestas was with Eumenes at his headquarters and allegedly panicked when he heard of the development, advising immediate flight. His commander was made of sterner stuff and responded with great invention. He ordered the units that were with them to light hundreds of their own campfires to give the impression to observers that the whole of the army was there. Again Eumenes’ cunning paid off; some shepherds, who had previously served with Pithon, when he was satrap of Media, saw the campfires and informed their former master that the whole enemy army awaited them at the edge of the desert. Antigonus and his officers, convinced that their surprise had failed, reluctantly redirected their route away from Eumenes’ headquarters. Bitterly disappointed, Antigonus took his men off to a position where they could camp in safety and comfort to recover from the rigours of the hard and ultimately futile desert journey.

Eumenes used the time his subterfuge had gained to send off to all the winter camps and ordered the units to converge on his own position. The vast bulk of his army had marched in and defended themselves in a palisaded camp by the time Antigonus was able to try to interfere. Antigonus knew he had been tricked but nothing could dampen his aggression and every reverse made him more eager to achieve something in compensation. The need to sustain his men’s confidence was pressing and the opportunity presented itself when he learned the enemy elephants had not yet reached the main army but were still plodding along a road nearby. He determined to ambush them; a success here might at least rectify the previous imbalance he had suffered from in this arm. He sent 2,000 Median lancers, 200 Tarentines and all his light infantry in an effort to cut off this slow-moving detachment. At first, it seemed his luck would hold. Overtaken, the elephants and their guard suffered considerably against greatly superior numbers of attackers. It would have been quickly over but for the officer in command of the elephants who kept his head and drew up the animals in a defensive square, with the baggage in the centre and 400 horse guards bringing up the rear. The Antigonid cavalry drove off the Eumenid horse but were unable to overrun the elephants’ formation because of the horses’ fear of their noise and smell but, even so, they would have succumbed had not Eumenes reacted quickly. Guessing they were in danger when they did not appear, he sent a relief force of 1,500 of his best cavalry and 3,000 light infantry. They arrived just in time and, taking the Antigonids by surprise, drove them off and escorted the bewildered but unharmed beasts safely to the main camp. Antigonus’ feelings of frustration can only be imagined, with all his best laid plans countered by an almost-miraculously well-informed rival.

But nothing could keep the effervescent old marshal down; he wanted to pin down and destroy these gadflies who had frustrated him at every turn since he entered the lands of Iran. ‘Antigonus perceived he had been out-generalled by Eumenes and in deep resentment led his forces forward to try the issue in open battle.’24 He was determined on battle and with his army rested he moved to bring it on. Days were short in this winter season and the weather was unpredictable but still he intended there to be a decision, he could not allow this war to drag on. Eumenes was also disposed to accept the test, he worried the Antigonids would get stronger with the passage of time and he always had the anxiety that his fractious army might split apart if not bolstered by a victory. The two armies found each other with ease and for a time manoeuvred, keeping several miles apart. But, this was just a preliminary, a warming up, for armies that in these cold and dismal circumstances were about to go at each other’s throats. The battleground has not been identified but it was known to have been a vast plain, largely uncultivated because of the salt content of the earth, and with a river something over a mile behind Eumenes’ position.

The night before the battle, Antigonus waited in some trepidation, at his camp on the higher ground above the plain. His men had surveyed the field of combat to ensure there were no unexpected effects of terrain or traps laid by the enemy. Now the 5,000-odd campfires he could see sparkling in the cold night air on the horizon really did represent the whole of his opponent’s army and from the experience of Paraetacene he had some understanding of their strengths and weaknesses. The Silver Shields, pikes bristling, were vicious fighters and would be formidable opponents even for the Macedonian veterans that Antigonus could field in even greater numbers. Whether they could stand against a push of pike with these violent old veterans was a very moot point indeed.

Antigonus was not particularly noted for his piety but on the evening before the battle he would have given offerings to any Hellenic deities that might have been observing the dramatic events in prospect, so far from his homeland. In open combat against the greatest general he would ever meet, he needed all the help he could get, particularly as the open country and mutual familiarity seemed to rule out any ruse that might have increased the odds in his favour. In his command tent the council of generals entered a tactical debate. Present were men who had made great reputations under Alexander. Pithon led the officers in discussion; he had shown himself to be a cautious but intelligent tactician in the past months and he, like the Cretan Nearchus, could talk from their experience in these very hills years before. But the one-eyed old general had the final say and the battle plan he favoured was much like the one he had tried to put into effect at Paraetacene.

The battle tactics of the Successors are often derided as a decline from the flexible use of all arms that had characterized Alexander’s genius. Although the assault on the right with a strong cavalry wing (the classic approach of the Successors) was clearly derived from the tactics of Alexander and Philip, it seems to have been an atrophied version. The subtle surgery of Gaugamela and Issus, where the infantry pinned down the enemy and the Companion cavalry carved a way to the centre of the opposition battle line, had degenerated from a deadly stab at the heart into a peripheral melee on the wings, with the outcome of the battle being decided by merely the brutal push of pike of the two phalanxes. But, in fact, this analysis fails to understand the differences in the problems faced by the men who came after, Alexander. He had confronted an enemy who, though numerically strong, could seldom field an infantry force capable of facing down charging cavalry in the open. Darius, and his generals, had squandered the majority of their good Greek infantry at Granicus and in the ensuing campaigns in Asia Minor. Without this hard defensive core, the Persian battle line was very vulnerable, once Alexander’s Companions had eluded the opposing cavalry. But in the inter-Macedonian affairs after his death, both sides could field a phalanx of levelled pikes at the centre of the line that could not be ruptured by an attack of horsemen, however disciplined or brave they were. Horses just would not throw themselves suicidally onto the line of spear points that faced a squadron coming in from the right centre. To disrupt and penetrate these fearsome formations, the cavalry had to get right round the flank or into the rear of the infantry. To do this required not just that the cavalry that defended the flank be fended off, they also had to be crushed and driven off to allow the time and space to attack the phalangites on their unguarded side. These cavalry fights on the flanks were longer and harder fought affairs which were often not settled before the foot soldiers had got at each other’s throats. And, the combat decided by a ferocious bloodletting in the centre of the battle line.

But, if new realities forced some changes in the pattern of battle, inevitably similarities remained and Antigonus, like his erstwhile king, used a deputy who could command on that side of the battle line, where he himself could not be. Pithon had taken on the mantle of Parmenion to Antigonus’ Alexander; he it was who held the left wing tight while his commander took the offensive on the right. The comparison does not stop there, he (like Alexander’s general) urged caution when Antigonus inclined to a too adventurous strategy.25 And, like his role model, Pithon would suffer at his leader’s hands when it seemed his power was at its height; though Antigonus had more cause than Alexander for the radical disposal of his right hand man.

For this the decisive encounter, the details of the formations are sketchier than in the previous one. But, as the tactics decided on by Antigonus very much mirrored those at Paraetacene, we can reasonably assume both cavalry wings were composed roughly as before. Pithon was apparently given fewer men this time, about 4,500 horsemen to again hold up the left flank of Antigonus’ array and by skirmishing occupy the enemy horse opposite him. Whether this smaller number of men was due to attrition from the previous battle and desert march or if the previous higher figure was exaggeration is unclear. His forces would have comprised Median gentry from his own satrapy, splendid in their colourful trousers and caps. The wealthier men wore gilded body armour that extended to frontal protection for the horses they rode. They had been, with their Persian cousins, the backbone of the Achaemenid imperial army and in a new world the fighting spirit Alexander had recognized had not deserted them.26 The horses they rode were some of the best in the world. Pithon would also have commanded mounted archers from Parthia whose descendants, under the leadership of a Scythian ruling clan, would inherit the eastern Empire of Darius and Alexander in just over a century’s time. We are not told where the 1,000 Phrygians and Lydians, the Tarentines, the lancers of Lysanias, the two horse men or the up-country colonists were, but they were presumably under his command too.

These units were designed to absorb the blows of their opponents and not give way. As at Paraetacene, they were not expected to make the decisive breakthrough but to occupy the right wing of Eumenes’ army while Antigonus and his son led their own right hand flank to victory. Demetrius, we are told, now commanded the whole of the right wing, not just the Companions, but no explanation is given of why the change was made. It is possible that Antigonus was gradually increasing the responsibilities of his heir as a part of his education in power, and as Antigonus, himself, remained in the same part of the battlefield he could supervise or take direct command if necessary. At this station of honour on the right flank were about 4,000 horsemen, whose equipment, morale and discipline were second to none; the very heirs of those men who had chased Memnon, Darius and Porus off the battlefields of Asia. There were hundreds of picked Greek mercenaries and 1,000-odd ferocious Thracians, wild and uncivilized but well armoured and brave; we know of them from the previous battle and they almost certainly were arrayed on this wing. And then there came the Companions themselves, almost 1,000 strong; the very best of Antigonus’ Macedonian horse, with a sprinkling of Greek and Levantine aristocrats, armed and mounted to perfection. The commander-in-chief, a huge man in breastplate and crested helmet, would have seemed almost a mythical giant, on the biggest Nicaean horse that could be found, as he dressed the line and took up his place with his glamorous son at the head of the right flank cavalry. The customary appeal to the army dwelt on past success; he reminded them of their victories over the last few seasons. How Alcetas, Arrhidaeus, Cleitus had all fallen before them and that having chased Eumenes from Cappadocia to central Iran they could now finish off this pest too.

The dressing and encouraging of huge battle lines of around 40,000 men a side must have taken much of the short winter morning, before any blows were exchanged. Eumenes, seeing how his opponent had deployed his army, decided to arrange his men in exactly the opposite way. He took command on the left wing directly opposing Antigonus. Against his enemy’s 4,000 or so, he fielded his best cavalry. He positioned himself on the left of these squadrons with his personal guard and perhaps again, as at Paraetacene, supported by the 300 selected best of the satraps’ horsemen. After them came the massed retinues of the eastern satraps, splendidly armed and mounted heavy cavalry intended to close and fight hand-to-hand. The end of the left wing nearest the infantry centre was held by Peucestas and his Persian cavaliers, whose ancestors had conquered the world under Cyrus and Darius I. Indeed, at this point Diodorus emphasizes the Iranian dimension by mentioning the presence of one Mithridates, whose lineage went back to the seven illustrious warriors who killed Darius I’s rival and helped that great man to his throne. In front of the horsemen were sixty elephants, spread in a curve that extended around the far left of the cavalry line. They are described as the strongest of these beasts in the whole army and the intention was that they would stop Antigonus from using his superior numbers to outflank Eumenes.

On this side of the field, Antigonus had only thirty or so of these beasts to face the enemy’s 60 but they (like their counterparts all along the line) stood forward to begin the battle when the trumpets sounded the advance on both sides. The dust these animals and their infantry guards kicked up as they jousted with each other was incredible. The loose saline soil rose like a thick mist to obscure the position of both friends and foe for several minutes at a time. Even before the real battle had begun between the cavalry and infantry, Antigonus decided on a stratagem to utilize this peculiarly poor visibility. He had been informed that on Pithon’s flank the enemy had not extended the elephant line to prevent outflanking, so he sent to his subordinate to try a raid wide out to his left. Diodorus’ wording actually suggests that the troops in this enterprise came from Antigonus’ own wing, but the fact that they are specified as Medians suggests they were Pithon’s men. Whatever, a detachment was organized and orders given for the squadron leaders to gallop around the elephants and the enemy formations whose armour could be glimpsed shining through the choking air. The dash through the dust, around the enemy flank, took the Medians and Tarentines out behind their opponents’ battle line and ahead of them they saw the pack animals and loaded carts of the enemy baggage camp. The booty of years of campaigning, protected only by unarmed non-combatants, drew them on like a magnet and soon the whole camp was in uproar with the overrun defenders captured or killed. No line of reserves was there to help out, and the whole of their adversaries’ material wealth came into the hands of Antigonus’ men.

This manoeuvre is claimed as intended, Diodorus states that ‘such a cloud of dust was raised by the cavalry that from a little distance one could not easily see what was happening. When Antigonus perceived this, he dispatched the Median cavalry and an adequate force of Tarentines against the baggage of the enemy.’27 But to be sure of this is to try and resolve an insoluble mystery. To unravel the plans and events in ancient battles is a notoriously pitfall-ridden form of analysis. The probability is that an outflanking manoeuvre was ordered but once this was accomplished the capture of Eumenes’ baggage camp was an act of inspired local initiative.

What is certain is that Antigonus had little leisure to think on the implications of this local success (even if he was aware of it) in the maelstrom of events elsewhere. The squadrons under his command each formed in offensive wedges and tried to manoeuvre through or around the elephants in preparation for an attack. On this occasion, sufficient gaps showed in the ranks of enemy beasts and light infantry in front so that Antigonus was able to lead his own wing forward against Peucestas, immediately opposite. That he aimed here, rather than directly for Eumenes, suggests he intended to force a gap between the enemy’s left wing cavalry and their infantry centre just as he had so successfully at Paraetacene. The satrap of Persia fled, taking with him not only his own followers but also 1,500 troopers that were posted next to him in the line. These must have been mostly from the eastern satraps’ retinues and suggests subversion or disenchantment with Eumenes amongst a large group of his allies. The dust of the retreating masses of enemy cavalry was a gladdening sight to the Antigonids clamouring for pursuit but they were not allowed the opportunity to succumb to this temptation. Eumenes could move his cavalry regiments quickly too, when required, and he responded to events by leading his own squadrons to attack Antigonus.

The Cardian showed extraordinary spirit against an antagonist who had outnumbered him even before over half his horsemen had fled; ‘preferring to die while still upholding with noble resolution the trust that had been given him by the kings’.28 Many of the men left were his own Anatolians and personal companions, who had been with him since the triumphs on the Hellespont and the setbacks at Nora. And, on his side, he had his sixty strongest elephants that might contain the enemy horsemen by their presence and stop them from exploiting the gap left by Peucestas. It was a bloody phase of the battle with charge and countercharge and generals fighting hand-to-hand alongside their men. It is, indeed, clear Eumenes hoped to bring down Antigonus personally as he had Neoptolemus on a previous occasion. Apparently, ‘he forced his way towards Antigonus himself ‘, but this time no such epic duel occurred and in this encounter the elephants were the key; while Eumenes’ animal line held, Antigonus could not bring all his extra horsemen to bear.29 ‘It was at this time, while the elephants also were struggling against each other, reports Diodorus, ‘that Eumenes’ leading elephant fell after having been engaged with the strongest of those arrayed against it’.30 With their leader down, these unreliably belligerent beasts gave up the struggle and it became apparent to Eumenes that his position on the left was untenable.

Leaving that part of the battlefield to the victorious enemy, with what men he could rally he withdrew to join Philip and the cavalry on the right flank. If in the fight on the left numbers had won out, the very opposite had happened in the centre. The Antigonids fielded 22,000 men in their phalanx, 6,000 less than at Paraetacene, indicating not just the inroads of the previous battle but the debilitating effects of the desert march. Assuming an even spread of casualties, 6 or 7,000 Macedonian phalangites must have remained to take up the position of honour on the right of the line. Next to them, the same number of other nationalities drilled and armed exactly as the Macedonians were. Then, between 7 and 8,000 Greek mercenaries and the balance made up of Anatolians from Lycia and Pamphylia, long-time loyal subjects of the Antigonids, all armed as hoplites or peltasts. Against them, waiting in the dust behind a line of 30 elephants, were 17,000 foot, deployed in a somewhat unorthodox manner. To ensure the Macedonians in Antigonus’ phalanx were opposed by his best men, Eumenes had reversed the normal order of battle (just as he had with the cavalry opposing Antigonus). The 3,000 hypaspists, instead of the usual position of honour on the right, took post on the left of the phalanx. Next to them stood the Silver Shields, also to the number of 3,000, and then 11,000 ‘mercenaries and those of the other soldiers who were armed in the Macedonian fashion’.31 We know from the previous encounter that 5,000 of these had been armed as pikemen but it may be that all the rest had now been so equipped and drilled. If this is the case, it might give some explanation of the ease with which they triumphed over an enemy who still fielded many troops carrying shorter spears. But, equally, it may be a mistake of the sources, as one must question whether even the extraordinary ability of Eumenes could reform and retrain these men in new arms and tactics in the short space of time between the two battles.

This encounter was preceded by some psychological warfare orchestrated by the general commanding the Silver Shields. Opposite them were Macedonian compatriots but men of a younger generation and, playing on a hoped-for respect for their elders, Antigenes had his agents go and yell at their opponents that they ought to be ashamed to fight against the veterans who had fought under Philip and Alexander in the great days of Macedonian power. Antigonus’ men, who were mainly the younger levies brought over to Asia by Antipater in 320 BC, were affected by this and there were elements who were reluctant to raise their pikes against such national heroes. The veterans themselves had no such qualms about whose blood they spilt but were prepared to play the psychology game, shouting: ‘It is against your fathers that ye sin, ye miscreants’.32

Then, on Eumenes’ orders, these preliminaries were ended with instructions for the whole phalanx to prepare to attack. After the elephants had cleared the way, the awful lines of pikes faced each other. What is never explained in any of our sources is how a clear run was given to the phalanx infantry with many tens of elephants and thousands of their infantry guards fighting between the lines of pikes as they approached each other. Accounts of battles fought by Romans against enemy elephants suggest that they allowed lanes for the beast to be corralled down, but this is never mentioned in the sources for our period, and anyway unwieldy phalangites might have found this more difficult than the more flexible legions (though at Gaugamela they are described as forming lanes for Darius’ chariots to harmlessly career down). Perhaps the phalangites were trained to push through the animals and men in front of them but unfortunately this process is not explained. This may be another reason to question our sources that try and paint the Macedonian formation as a clumsy battering ram, only effective when undisturbed by terrain or events.33

However they got to each other, they certainly did and the front ranks fell in heaps on both sides but, while the Antigonid foot were distressed by their losses, the Silver Shields and their comrades ploughed on unheeding. Like a steamroller they pushed over the enemy phalanx, though they were themselves far outnumbered. The hypaspists, no doubt, were alongside them in the fray but even with this support the Antigonids had several thousand more pikes at that part of the front. But this push of pike was a matter of discipline and morale, not numbers. In this rush of bristling enemy spears 5,000 of Antigonus’ infantry fell, and after such loss of life retaining cohesion and discipline was out of the question. The bodies lay in piles, but the cutting edge of the veterans was hardly blunted as they chased the fleeing enemy off the battlefield over a litter of discarded sarissae.

Eumenes had expected to win his victory with the infantry and again they had done their job. But if events in the centre had seen his troops victorious, elsewhere it was a different matter. Philip, the commander on the allied right, had considerably fewer men than Pithon was fielding.34 They were mainly light-armed cavalry who had been on the left under Eudamus at Paraetacene. They would presumably have again been the Arians and Drangians under Stasander, Paropamisadae under Androbazus and perhaps the colonial Thracians and Mesopotamians as well; mainly mounted javelineers, mountain Indians from the Hindu Kush and light horse from the eastern satrapies in the main. Their bravery was never in question but their equipment and tough, light horses, whilst effective for skirmishing, would never allow them to hold the line against Macedonian Companions or Nicaean-mounted Medes. The best of the satrapal horse had been stationed on the left to support Eumenes and Peucestas. Philip’s regiments had, at least, occupied the enemy wing opposite, the horse and elephants in front had held the right wing tight as we hear nothing of Pithon’s main force making headway against them as had happened in the early stages at Paraetacene.

To regain the initiative against Antigonus’ rampant right wing cavalry, Eumenes needed the aid of Peucestas and his Iranian cavaliers who had fled at first contact with the enemy. He rode across to plead with his lieutenant but the satrap of Persia remained unmoved. ‘Since Peucestas, however, would not listen to him but on the contrary retired still farther to a certain river.’35 This must have been a dramatic encounter with few parallels in the pages of history but what is clear is that treachery had bitten deep into the ranks of Eumenes’ generals and this was only the first of many bitter blows he would take from his own side during the next few hours. All was now confusion, over a battle line that stretched well over 2 miles in width. Opposed to Pithon were Philip and Eumenes, who, despairing of Peucestas and the others, had returned to his intact right wing with what remained of the routed left wing cavalry. In the centre, the ruin of Antigonus’ phalanx was complete with the Silver Shields and hypaspists chasing them far from the battlefield. But Antigonus had the priceless asset of the allied baggage train. Antigonus’ personal retinue kept him protected from the dislocated enemy units that careered over the plain whilst he tried to make sense of the chaos – the ultimate test of his generalship. The confusion in the reports of these battles must never be underestimated but, in this instance, we are fortunate that the original source for the events was a very competent eyewitness. Hieronymus of Cardia was able to record the course of the combat from the mouths of the contestants on the very heel of events. Their comments would have been partisan but fresh and, as far as is ever possible, the manoeuvres described at Gabene must be an accurate reflection of what actually happened.

Out of all the disorder one action, at least, is attested not just by its description but also by the events that resulted from it. While Antigonus sent orders to Pithon to attack the enemy infantry and he himself faced Eumenes’ remaining cavalry, his officers made doubly sure that the enemy baggage train was made safe against counterattack. The Antigonid left, under Pithon, turned about and came in behind the enemy infantry, who were still in pursuit of the crumbled remains of the Antigonid phalanx. Yet, as they drew up in ordered squadrons in the rear of the Silver Shields and their comrades, they did not find easy pickings. These old sweats knew the tactics to counter this danger and ‘formed themselves into a square and withdrew safely to the river’.36 This is a remarkable testament to the qualities of phalangites already engaged in combat; to pull themselves up from pursuit and reorganize to show a hedge of bristling spears all round to the oncoming cavalry. With the salt soil in everyman’s throat and night already on them, the generals on either side had no real idea of the overall situation. To reform and reconsider was the reality forced on them all and this breathing space became the end of the battle. In the dark, acrimonious debate characterized the council of Antigonus’ enemy; Eumenes wanted to carry on the fight the next day, to exploit the virtual elimination of the Antigonid infantry as an organized force. His satrapal allies showed less fight and wished to retreat deeper into Iran. Revealing little belligerence in the battle, many perhaps shared whatever motive caused Peucestas to flee from Antigonus’ cavalry.37

The atmosphere in the coalition bivouac as the soldiers settled down for what could only be a short night’s sleep was very fraught indeed. Every man saw a traitor in another part of his own camp as well as feeling the ever-present threat of the Antigonid army over the horizon. The infantry knew that Peucestas and his Iranians had badly let them down by decamping without a fight and they were not backward in expressing their disgust. But, while cavalry and elephant-handlers looked to feeding and bedding down their beasts, the senior Macedonian infantry began to confer on a future that had their own very direct interest at its heart. The Silver Shields are specified but it must have been others as well who began to debate how to get back the baggage train that contained both the treasure and the families of these phalangites who had just fought so hard and successfully for their generals’ cause. This was a roots-up movement (subsequent events showed that Antigenes and Teutamus would not have instigated any approach to Antigonus who was their vicious enemy) and with breathtaking felicity this Macedonian infantry ‘co-operative’ came to a decision. When their envoys found that Antigonus would only disgorge their worldly goods for Eumenes himself, they determined on the swap and marched to their commander’s headquarters.

The Greek general was disarmed and restrained, despite some who felt ashamed of handing over their old chief, and word sent to Antigonus that he had been taken. He and Antigonus may have been personally quite close and had certainly known each other over many years. But he was too dangerous not to be eliminated and was executed. Antigonus could be generous to defeated foes but not in this case; the Cardian had cost him too much effort, given him too many frights and outwitted him once too often. Antigonus had sneaked success at Gabene but it was still decisive, for now he and his faction were the great power at the heart of the post-Alexandrine world.