Antigonus had been the centre of the military world of the Diadochi since he took up the command against the Perdiccan remnants after the Triparadeisus settlement and would remain so until almost the end of the century. But the next battle we can consider in detail, after the duel with Eumenes, saw him take no direct part despite the fact that his faction provided one of the sides involved. This time it was his son, the young Demetrius, who was in command when the might of the Ptolemies tested the empire the old man had constructed in the years from 319 to 312 BC. Antigonus, himself, was at the time of the encounter exploring various possible options of crushing Cassander and Lysimachus who looked back at him from the coasts of Europe. These opponents had been, since the defeat of Eumenes, his highest priority but it was other enemies who precipitated the events that would dramatically impinge on the military fortunes of his offspring.

It was the first time young Demetrius had left the protective shadow of his father. Antigonus had previously mainly used his nephews as lieutenants in independent commands but, at last, in his early 20s, his son and heir was to be trusted with major responsibility. From the time the elder Antigonid crossed the Taurus in late winter 313 BC to when the Byzantines scuppered his attempt to get at Lysimachus and Cassander in Europe, Demetrius had been in command in the Levant. This was a core region for the family’s wealth and power; it was studded with cities rich from trade and manufacture and, apart from anything else, was the source of many of the naval squadrons that ensured the Antigonids’ real control of the east Mediterranean seaways.

A council of veteran advisers were left with him to guide his steps in the crucial task of defending the Antigonid frontiers where they abutted those of their Ptolemaic rival. One of these men was Nearchus, the friend and admiral of Alexander, who had been with Antigonus for years and is mentioned in a command position during the march through Cossaean territory that so nearly ended in fiasco. Pithon (another Pithon, not the satrap of Media) was another, who had recently been made satrap of Babylon replacing Seleucus, even though he had first fought for Eumenes, after coming up from his post in India. There was Andronicus the Olynthian, who is unknown under Alexander but had commanded the siege camp at Tyre when Antigonus struck with his main army against Joppa and Gaza; and Philip, another who had held a command in the upper satrapies and had served under Eumenes before joining the Antigonids.1 The last member of the council we know of only from the battle casualties; this was a Boeotus who we learn ‘for a long time had lived with his [Demetrius’] father Antigonus and had shared in all his state secrets’.2 Most of these had been stalwarts under Alexander and together represented a considerable aggregate of experience and talent to advise the 22-year-old who now, for the first time, held independent command.

Demetrius had been left by his father with a considerable field army which he surely expected would face up to anything that Ptolemy might throw in his direction. These defensive arrangements were not immediately tested but then, in early 312 BC, the Egyptian satrap attacked north Syria and Cilicia. Several cities were sacked before Demetrius took action and saw the intruders off with some aplomb. The young Antigonid, in his first real test, showed well and after these efforts he and his men returned to Coele-Syria, which he had left in the care of Pithon, to enjoy some of the amenities of home. Since Alexander passed that way a number of Hellenic cities had been planted, where demobbed soldiers or enterprising civilians could provide the taverns, brothels, theatrical and musical entertainments and market produce to please the palates of men who came mainly from Europe or Asia Minor. Demetrius, no doubt, enjoyed his share of distractions; he certainly gained a reputation for enjoying his portion of debauchery in later life, but he had responsibilities too. Most particularly he needed to replace the cavalry mounts that had been lost in the hard march to Cilicia where ‘on account of the excessive hardship not one of his sutlers or of his grooms kept up the pace’.3 Fortunately, for him, in Media and Anatolia the Antigonids controlled lands where some of the best cavalry horses in the world were reared. But, the recuperation that the coming of winter normally brought was to be cut very short for the young commander and his relaxing soldiers. Ptolemy had organized a major army to continue his assault while Antigonus was still occupied in the west. Despite the winter season, he attacked directly, forcing Demetrius to prepare to defend the frontier of his father’s empire.

We have noted previously that fighting in winter was still unusual, yet, while this remains true, at least three of the major battles in this history took place in that season. Paraetacene and Gabene, as well as Gaza, all occurred deep in winter and though all were fought in latitudes that meant the weather would not be completely debilitating it is still an interesting statistic. These Successor generals were not hidebound traditionalists. Just as that early Macedonian military revolutionary, Philip, would continue to fight when the time of year ought to see the soldiers back home on their farms, so would they. Even in the not-excessively severe climates of the Levant and Iran it was still difficult to operate in the winter months and in any case the crucial factor in this was social not meteorological. What Philip could occasionally do, with his core of mercenaries and a peasant levy which might make arrangements to stay on campaign when they would normally be on the farms, the Diadochi could do as a normal practice. The soldiers of 317 and 312 BC had no immediate farms to return to, in the way their predecessors had, and were available for their masters to call to arms all year round. Their homes were their baggage trains and encampments and these could function twelve months of the year.

The Battle of Gaza took place where now the mixed poison of neocolonialism and monotheism has crushed the lives of people who 2,300 years ago would have given a more reasonable tithe to their gods and carried on with life more rationally than their descendants do today. Satellite imagery in the twenty-first century shows mainly a mass of dwellings very unlike the much less inhabited region fought over in 312 BC. The fighting occurred somewhere to the south of the old city of Gaza which had itself suffered much from Alexander’s passing army a couple of decades before. The invading generals who now arrived there from the south had something of a military ragbag at their backs. The exact details of Ptolemaic Egypt’s military establishment are not easy to accurately analyze. As a beginning, a garrison of 4,000 infantry and 30 triremes had been left there by Alexander, when he departed to confront Darius, and presumably they were mainly still in place when Ptolemy took over in 323 BC. These are described by Arrian as being based at Pelusium and Memphis and consisting of mercenaries. They were not front-line Macedonian phalangites and this suggests a reason why Ptolemy declined to face Perdiccas in open battle when the regent invaded Egypt in the first civil war. He also was, anyway, considerably outnumbered by the invader.

In this campaign, Ptolemy and Seleucus travelled from Alexandria but the army concentrated at Pelusium, further to the east. If the forces Ptolemy inherited on his arrival in Egypt had not been large, he had done all in his power to increase it in the meantime. An effort that allowed him to field an invasion force of 18,000 infantry and 4,000 horse. Some were Macedonians, which indicates a core of phalangites. But, their numbers must have been small, perhaps no more than a few thousand, comprising largely the men who had come over to Ptolemy’s side after the defeat of Perdiccas. The bulk of the regiments Ptolemy led forward were made up of Hellenic mercenaries. These men, many of whom would have begun their career under Alexander, had thrived on the business of war ever since. Their calling in those days was considered honourable and a more pragmatic morality saves them from the pejoratives that sit naturally on their historical heirs, who have made the name mercenary an accusation rather than a description. They mainly came from the east Mediterranean littoral where Ptolemy’s fleet allowed him easy access. Ptolemy had plenty of money to spend on them; he had taken 8,000 talents from Cleomenes who had been in command of Egyptian finances for some years before Ptolemy’s arrival and who he eliminated straight away, despite Perdiccas having designated the Greek financier as his deputy in the Babylonian settlement. Apart from these veterans for hire, Seleucus would have brought several thousand troops from the army he had been shipping round the Aegean and east Mediterranean for the last two years. But, if this collection of foreigners provided the bulk of both the horse and foot there were also, apparently, many Egyptians present. This comes as something of a surprise as it was not until the Battle of Raphia in 217 BC, at a time when Antiochus the Great threatened the very existence of the Ptolemaic state, that indigenous solders were incorporated extensively into the fabric of the royal army. At that time, Egyptians were drilled into proper heavy infantry and, in fact, these local troops provided most of the main phalanx. And at Raphia it was their efforts in the crucial push of pike that mainly decided the battle, despite Antiochus driving off the Ptolemaic cavalry wing that he personally encountered during the battle.

That Hellenic xenophobia over arming the subject population was overcome as soon as 312 BC is extremely unlikely. Ptolemy and his people had only been in power for a decade and fear of a well-equipped native army as a tool of national rebellion would surely have been at the forefront of their minds. The Persian control of the country had been constantly disrupted by such independence movements. Defeat by Macedonian rivals could have dreadful consequences but not to the same degree as a national rebellion. It is certain that the people Diodorus describes as ‘a great number were Egyptians, of whom some carried the missiles and the other baggage but some were armed and serviceable for battle’ refers to servants or skirmishers, not front-line foot soldiers or cavalry.4

The army travelled the coast road with the bitter desert on their right and the blue sea on the left. The campaign plan was to take Gaza, the gateway to Palestine and from there on towards Coele-Syria and Phoenicia. This was a route that Tuthmose III and Ramses II had taken in the distant past to gain what Ptolemy had so far not, a lasting empire of the Levant. It was only a few days’ march, but in that time Demetrius’ soldiers had been massing in the rough barren country south of the old city. His army had been wintering in their billets near the southern frontier when word of the Ptolemaic invasion arrived and concentration on their headquarters at Gaza had been easy. The decision of the Antigonids to hold their ground, however, had not been automatically agreed and conflict marked the war council in the hours before the battle. Those officers left to guide the steps of Demetrius apparently opposed offering battle on the ground of the enemy’s greater numbers and the military reputations of Ptolemy and Seleucus against the untried Demetrius. Though some hesitation before the fight is believable, the reasons given do not make complete sense. Certainly there was a disparity in the size of the opposing phalanxes, but as for the second argument, the very presence of a veteran group of advisors was intended to make up for the difference in experience between the commanders-in-chief.

This attitude of Demetrius’ advisors to Ptolemy is interesting, if it is to be believed, because if his overall career shows him as a cautious, sometimes-irresolute imperialist, what this indicates is that at this period he was seen by contemporaries as a very great military figure.5 He had fought with Alexander through all the glory years, he had been a bodyguard of the king and had fought a great set-piece duel with an Indian chieftain. He had possibly brought in Bessus, the Persian pretender, captive to receive Alexander’s tender mercies and since Alexander’s death he had conquered Cyrene, defeated Perdiccas, the great king’s successor, personally commanding at the Camel Fort, and never yet been bested in battle. He was a great figure and now he was seconded by Seleucus, who could also boast a pedigree going back even before he commanded the king’s guards (hypaspists) when they bore the brunt of the fighting in the battle against King Porus in 326 BC.

Whatever their individual ruminations, once the decision to stand was made a battle became inevitable and it seems neither side tried to manoeuvre much to gain advantage before they came to blows. But if the Antigonid had not been hard to find, Ptolemy did not rush to engage but camped to rest his men before the encounter. Demetrius was buoyed up by encouragement of the soldiery:

When he had called together an assembly under arms and, anxious and agitated, had taken his position on a raised platform, the crowd shouted with a single voice, bidding him be of good courage…For, because he had just been placed in command, neither soldiers or civilians had for him any ill will such as usually develops against generals of long standing.6

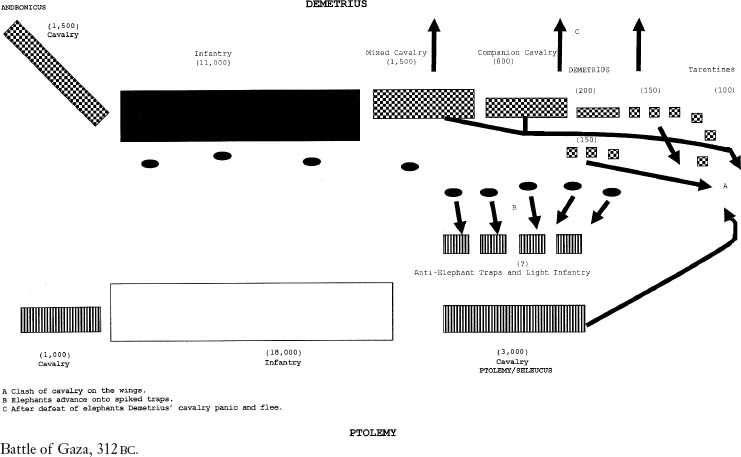

He decided to attack; in his life he seemed to know no other way of fighting. A cavalry assault on the left and the ponderous weight of his elephants (against an enemy who possessed none) he hoped would bring an easy victory. In infantry he was at a disadvantage; his phalanx comprised only 11,000 men, of whom 2,000 were Macedonians and another 1,000 were Anatolians (Lycians and Pamphylians). The latter are differentiated from the rest, as they had been at the battles in Iran, perhaps because they had long been regular soldiers of the Antigonid army. They, after all, came from countries that were close by the satrapy in Anatolia that Antigonus had governed since as far back as the 330s BC. The remaining 8,000 were mercenaries. This infantry force is definitely depleted from the 13,000 left Demetrius when he first took up his vice regal role; 2,000 mercenaries had been lost, but as wastage from over a year’s campaigning perhaps this is not excessive. Most of these heavy infantry would surely now have been sarissa-wielding pikemen, there had certainly been a long enough period to re-equip and train those who were not so accoutred previously. To compensate for the disparity in the centre, where the enemy fielded 18,000 infantry, his own 11,000 foot soldiers were preceded into battle by 13 elephants and their light infantry guards.

No important role was envisaged for the right wing. Andronicus commanded 1,500 horse here and they were held back at an angle from the main battle line. The use of this oblique formation was more radical in intention than usual. The Antigonid high command did not just plan that their right wing would hold back in its attack, it was intended that this, the weaker flank, would not be strongly tested during the combat and, if possible, remain out of contact altogether. It, at the beginning, seemed an intelligent ploy but less so as the day developed with Ptolemy weakening his own forces on that part of the battlefield to the extent that Andronicus was eventually left with a three to two advantage in men on his front. The ploy of holding back a wing was one Demetrius was familiar with, from when he fought under his father in the great battles against Eumenes at Gabene and Paraetacene. On both occasions it was the left wing which had instructions from Antigonus to skirmish or hold back until the battle was almost won by the infantry phalanx or the heavy cavalry on the right.

Ptolemy foresaw the danger from the Antigonid elephant corps. He had none of these beasts himself; he had brought none from Babylon and was never in a position to recruit them from Asia. Not until the reign of his son did the Ptolemaic military establishment exploit the resources of their own continent to fill the gap. From Ptolemy II Philadelphus’ time regular hunting expeditions marched south deep into Ethiopia to capture the forest elephant, indigenous to parts of ancient North and East Africa. This species, now probably extinct (though a similar African forest elephant does survive) were far smaller than the African elephant that inhabits the tropical country to the south and indeed considerably smaller and weaker than their Indian cousins introduced into Hellenic warfare by Alexander. In the Battle of Raphia, almost 100 years later, the smaller species did not hold up well against the bigger ones when they met head to head. That said, in a different time and place, the great Hannibal had enough faith in the African beasts to make great efforts to ensure some were available for his battles with the Romans.

The Ptolemaic high command was familiar enough with the elephants’ powers since their days in India and knew their weaknesses as well; one of which was that the soles of the animals’ feet were very tender. A deterrent was prepared that mirrored the technique used by Damis at the siege of Megalopolis six years before. They constructed a form of caltrop, from planks with nails embedded in them, that pointing upwards would severely wound any animals that trod on them. The traps were portable and connected by chains and were used to protect the army’s right flank. They may have been planted in front of the infantry phalanx as well, though their presence there was likely to have impeded the tightly packed pikemen when they tried to push forward to attack their less numerous opponents. It may well have been the view that the serried ranks of the infantry sarissae would be enough to keep the belligerent but temperamental beasts at bay.

If intelligence on the composition of Demetrius’ army was sound, it appears from the preliminaries that the same was not true in respect of their disposition. Ptolemy and Seleucus had concentrated their strength on the left flank, only to find out from their scouts, that Demetrius had deployed his best horse on his left (opposite the Ptolemaic right) where the young Antigonid hoped to open the battle. This called for some swift adjustment and most of the troopers from the Egyptian left wing were brought over to the right to counter Demetrius’ planned assault. Three quarters of all Ptolemy’s cavalry, 3,000 horsemen, were eventually deployed in serried ranks on the right flank. So, only 1,000 were left to face Andronicus. All this must have taken a little time, and, as the winter day would anyway have been short, it suggests the battle could not have commenced until the day was well underway.

The composition of the Antigonid left wing, led by Demetrius, is known in some detail. The young general, himself, was stationed at the outer edge of the formation with 200 guard cavalry and kept company by Pithon (who seems to have acted as a co-commander in the battle) and most of his other friends and councillors. Also 300 more troopers were placed as advance and flank guards for the units around Demetrius and, reading Diodorus, it is difficult not to feel that these dispositions were made with protecting Demetrius’ life very much in mind. The advisors left by Antigonus were determined they should not end up with the task of reporting to Antigonus the death of his favourite son. These 500 troopers were all specified as being armed with lances, but whether this would be the longer sarissa which was usually carried by light horse, or the shorter cornel wood spear of the heavier horse we are not sure. It is not, however, unreasonable to suggest they were heavy cavalry as these were usually the troops that were led by the commander who made the decisive assault. Whatever the case, out in front of all these were stationed 100 Tarentines, a warrior type that had only surfaced in the past few years. Having proved their worth in Antigonus’ campaigns against Eumenes they had remained on the payroll and, though meagre in number, they were considered effective in disrupting enemy formations before the heavy squadrons were brought into play.7 Then, next on the left were 800 Companion cavalry, all Macedonians, and on their flank ‘fifteen hundred horsemen of all kinds’.8 This was 600 horsemen fewer than Demetrius had inherited when Antigonus left him, indicating he had perhaps not completed the cavalry refit after the brutal march to Cilicia. In front of them were thirty elephants which, with the thirteen spread thinly along the front of the infantry phalanx, made up the forty-three originally left to Demetrius by his father.

The Battle of Gaza was fought and won on Ptolemy’s right but the first round was far from a success for his men. We hear of a conflict at the extremes of his right wing, between the advanced guards, beginning the battle. Demetrius’ men proved too strong for the troopers of Ptolemy’s vanguard who were badly beaten up. To remedy this development, Ptolemy knew he must support his forward units but with the elephants between the lines he could not directly attack the enemy horse. To bring numbers to bear, he ordered a large proportion of the cavalry to move to the right around Demetrius’ flank. Both Ptolemy and Seleucus led these squadrons, who were drawn up in depth, to give extra impetus to their charge. The impact of this outflanking move initially fell on the 1,500 mixed horse on the left of Demetrius’ line. The struggle is described briefly but dramatically:

In the first charge, indeed, the fighting was with spears, most of which were shattered, and many of the antagonists were wounded; then, rallying again, the men rushed into battle at sword’s point, and, as they were locked in close combat, many were slain on each side. The very commanders, endangering themselves in front of all, encouraged those under their command to withstand the danger stoutly.9

After the cavalry fight had been in progress for some time, the thirty elephants of Demetrius’ wing were ordered forward to make the decisive breakthrough and drive a wedge through Ptolemy’s battle line and expose the flank of his infantry. The animals and their drivers had no warning of the deadly spikes waiting in their path; and, more than this, when they blundered into the trap and were brought to a halt, they found Ptolemy had concentrated all his light infantry, who began to fire at the elephant drivers with their javelins and arrows. The beasts could not be driven through the barrier of spikes and with their drivers being shot down they panicked:

And, while the mahouts were forcing the beasts forward and were using their goads, some of the elephants were pierced by the cleverly devised spikes and, tormented by their wounds and by the concentrated efforts of the attackers began to cause disorder. For on smooth and yielding ground these beasts display in direct onset a might that is irresistible, but on terrain that is rough and difficult their strength is completely useless because of the tenderness of their feet.10

Diodorus tells us bluntly that the discomfitted elephants were all captured and that it was the sight of this defeat that caused Demetrius’ cavalry to give up the fight and run away. Though knowing his source at this point is most likely the usually accurate Hieronymus of Cardia, here common sense suggests Diodorus has not read him correctly. Elephants when gone berserk with pain from wounds in their feet and anger at the death of their mahouts are not readily susceptible to being brought under control. Though restrained and captured later, it is unlikely that many or any were taken at this juncture. Far more likely the animals ran amok back into the ranks of Demetrius’ cavalry. With their horses driven wild by the sight, sound and smell of the elephants so near them, the whole of Demetrius’ left wing dissolved. Leaving the young general to be caught up in the chaos and having to flee through the sunset plain to a place called Azotus, 30-odd miles from the battlefield.

But, whilst decisive events occurred on this wing, nothing is known of the rest of the battle. No mention of a contest between the foot soldiers is made, nor are infantry casualties detailed; only that after the battle 8,000 Anigonids (mainly infantry) surrendered to Ptolemy. Whether they stood and fought, fled or surrendered wholesale, they were no obstacle to the troopers who pursued Demetrius intent on filling their knapsacks with plunder from the baggage train left at Gaza. Their cupidity was facilitated by some of Demetrius’ own men who took off to Gaza to retrieve their baggage and, when they got there, inadvertently kept the city gates open by the press of pack animals they had gathered to help carry their goods away. In the confusion, few got away with their belongings and Ptolemy’s men were easily able to gain control of the city. The other wing under Andronicus also most probably saw no action with the 1,500 horsemen decamping when they saw the rout of the rest of the Antigonid army. In terms of battle casualties the Antigonids lost about 500 ‘the majority of whom were cavalry and men of distinction’11 as well as Pithon and Boeotus who also lost their lives in the fray.12

It is worth noting that this is the second time that we know of when a commanding officer specifically changed their original formation to beef up one of his wings, when they found out where their enemy had collected their best forces and clearly intended to make their main attack. At Gabene, Eumenes, finding that Antigonus intended to weight his right for the decisive attack, accordingly moved his best cavalry to his own left to oppose them. But, more than this, when he realized that Antigonus had placed his best phalangites on the right of his centre, Eumenes then placed his crack troops, the hypaspists and Silver shields opposite them on the left of his centre. Now, at Gaza, when Ptolemy’s scouts reported to him that Demetrius was concentrating his best horse and elephants on his left (Ptolemy’s right) he then changed his formation bringing over many of his horse from his left wing to have sufficient cavalry to compete with the enemy’s main thrust.

Aspects of this are difficult to interpret. Eumenes’ ploy makes sense in that he would have initially, as in the earlier Battle of Paraetacene, deployed his strongest wing on the right and also his strongest infantry units on the right of the phalanx, the usual place of honour (because it was usually the most dangerous side with the unshielded side exposed). But, when he was certain Antigonus was emphasizing his other wing he responded. However, at Gaza it seems Ptolemy had, against tradition, decided to make his main thrust from his left and only when he realized Demetrius was making his attack on the other flank did he adjust. It is possible he assumed that Demetrius would conform to tradition and lead from the right wing and so Ptolemy had intended to oppose him with his best men on his left.

The question that is begged was why on these particular occasions the parties readjusted but on others they did not. Presumably one factor was that they were able to do so. Before Gabene the armies approached each other from 8 miles away giving time for redeployment to occur and at Gaza, again, some time was available before the fighting began. But at Paraetacene, shortly before Gabene, it was a more confused affair brought on by Antigonus’ advance guard catching up with Eumenes which would not have allowed time for such a total redeployment. Clearly the tradition of the most prestigious units fighting on the right of the line was hallowed over centuries but it was far from an unbreakable rule. It had been breached by Epaminondas at Leuctra in 371 BC when he had brought the Sacred Band and his Boeotians to his left side, to ensure they would face the Spartans themselves, the strongest of his enemies. Even Philip, at Chaeronea in 338 BC, had posted the Companion cavalry under Alexander on his left to strike the fatal blow against the same Sacred Band, this time in the traditional place of honour on the right of the allied Greek line. Surprisingly Alexander had always conformed to the convention; in his four major battles he led the Companions on the right wing and the foot guards or hypaspists stood on the right hand side of the central phalanx. His Successors were more flexible but still, in most cases, conformed to what undoubtedly was expected by most of the troops. This is understandable and to change it willy-nilly might affect morale amongst extremely competitive warriors who valued reputation and worth almost as much as victory and loot. It is likely that if they did arrange their units in non-traditional fashion there would have been good reason for it.

That these officers of Alexander and their offspring were not always hidebound by tradition is equally shown here in that Demetrius was quite prepared to lead from the left, putting his best troops there as opposed to the traditional place of honour on the right. There seems no particular reason for this; the battle took place on an open plain, so terrain played no part in his decision making. Perhaps the reason was to do the unexpected, to try to outwit Ptolemy, and it almost worked with the enemy having to do some pretty sharp footwork to redeploy in time.

Another feature of this encounter is that the losing commander fled the field without apparently trying to get back to other parts of his army to try and retrieve the day. This was pretty unusual; most of the defeated generals we encounter either die where they stand, like Leonnatus or Craterus, or withdraw with their beaten forces like Antipater or Antigonus. The only other example in the battles of the Diadochi is Neoptolemus in his first encounter with Eumenes. But Demetrius at Gaza is the clearest example of one of them ‘doing a Darius’. And, the parallel goes further, Demetrius, we know, was very far from being a coward; in combat before and after he led from the front, fighting hand-to-hand on the model of Alexander and the same is true of the Persian great king. He was no weakling who fled at danger; he was, in fact, a famous duellist who had killed a Cadusian chief in single combat and as a usurper in the Persian court he had to possess reckless nerve. With him, one feels, it was the responsibility he embodied as Great King that encouraged himself and those around him to make his safety the top priority. And, with Demetrius, there will be some of this; he, too, was surrounded by men determined he should not come to harm. His youth and his inexperience in command may also have played a part.

Gaza, at first sight, looks like one of the most decisive victories of the Diadochi era. Demetrius was completely defeated with hardly even a remnant at his back as he trudged north with bitter ashes of defeat in his mouth and the whole Levantine coast open to the advancing Egyptian army. Sidon was soon taken but they were stopped temporarily in font of Tyre, where Andronicus had made his way back to from Gaza and put some steel in their defences. But, even this very defensible place was taken soon enough.13

In the long run, the most important outcome of this battling on the borders of Egypt and Palestine was to be felt hundreds of miles away. Seleucus re-appropriated his old satrapy of Babylonia before going on to build a state in Mesopotamia and Iran that effectively changed the balance of power in the Diadochi world. From Gaza to the great denouement at Ipsus in 301 BC there are no great terrestrial battles fought for which the sources gives us any great detail. As well as a short peace there was plenty of recorded conflict; many sieges (most notably Rhodes), a great sea battle at Salamis in Cyprus, skirmishing in Greece and Anatolia. There was also the largely unknown and unrecorded Babylonian war between Seleucus and Antigonus which ensured the success of the Seleucid comeback. There may even have been a great battle with Seleucus against Chandragupta Maurya in India but again we have no details which can add to our stock of knowledge about this particular aspect of the military life of the successors.

Artist’s impression of a Macedonian heavy cavalryman, based on the Alexander Sarcophagus. He wears a linen cuirass amd Boeotian helmet and is armed with a sword and long lance. (copyright J Yosri)

Bust of a Macedonian soldier of the late fourth century BC, now in Naples Archaeological Museum. (Authors’ photograph)

Artist’s impression of a typical phalangite, mainstay of most Diadochi armies. (copyright J Yosri)

Artist’s impression of a light infantryman or peltast, a common troop type in all Diadochi armies. (copyright J Yosri)

Artist’s impression of a war elephant. The use of howdahs to protect the crew in the wars of the first generation of Diadochi is speculative, their introduction often being attributed to Pyrrhus of Epirus. (copyright J Yosri)

Artist’s impression of an Iranian light cavalryman based on figures on the Alexander Sarcophagus. He is unarmoured, relying on speed and mobility to conduct hit-and-run attacks. (copyright J Yosri)

A detail from the Issus Mosaic, now in the Naples Archaeological Museum. It shows an Iranian cavalryman of the type that may have followed Peucestas or Pithon in the great battles of Gabene and Paraetacene. (Authors’ photograph)

Artsist’s impression of a Hellenistic lithobolos or stone thrower. (after Jeff Burn, copyright J Yosri)

An example of 4th/3rd century BC Hellenistic walls at the foot of Phylae in Attica, near Athens. Such fortifications of large, precisely-fitted stone blocks presented a formidable obstacle to besiegers. (Authors’ photograph)

Salamis port where Menelaus’fleet attempted to break out to join his brother Ptolemy but failed, allowing Demetrius to defeat Ptolemy in the epochal naval battle of 306 BC. (Authors’ photograph)