Lapped by the Java Sea to the north and the Indian Ocean to the south, the landscape of Central Java is one of fertile agricultural fields dotted with forested volcanoes. The region’s highlands, including mighty Gunung Merapi and less volatile Gunung Merbabu, give climbers, trekkers and birdwatchers ample reasons to come often and stay longer. Off the north coast, the Karimunjawa islands attract divers. To the south, the tempestuous Indian Ocean is flanked by beaches – some of black volcanic sand, some white-sand – offering freshly caught fish grilled to order. Part of the south coast is touched by a limestone karst mountain range riddled with caves, very few of which have been explored.

Central Java’s 35 million inhabitants live primarily in rural areas, where population densities are high. In the hinterland they are farmers and on the coasts they are fishermen, with a large number of handicraft-makers scattered throughout. North coast Semarang is the only industrial city.

The people of this region believe themselves to be ‘true Javanese’, descended from Central Java’s two great Mataram empires. The role of their royal courts as cultural centres is still deeply felt today. Often it is the cultural attractions that draw visitors here: the sombre stillness of ancient Hindu and Buddhist temples, the sequestered courtyards of its 18th-century Islamic palaces and its traditional arts: gamelan, shadow puppetry and dance.

A tobacco crop on the fertile soil of Central Java.

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

Much of interest is concentrated in and around the twin court cities, Yogyakarta (fondly called Jogja) and Surakarta (or Solo). It was here, on the well-irrigated banks of several adjacent rivers, that Central Java’s two great Mataram empires – one ancient and one modern – flourished. The role of the Javanese courts as cultural centres has long been recognised, but their vast catalogue of artistic wealth has only begun to be explored.

Yogyakarta and its region

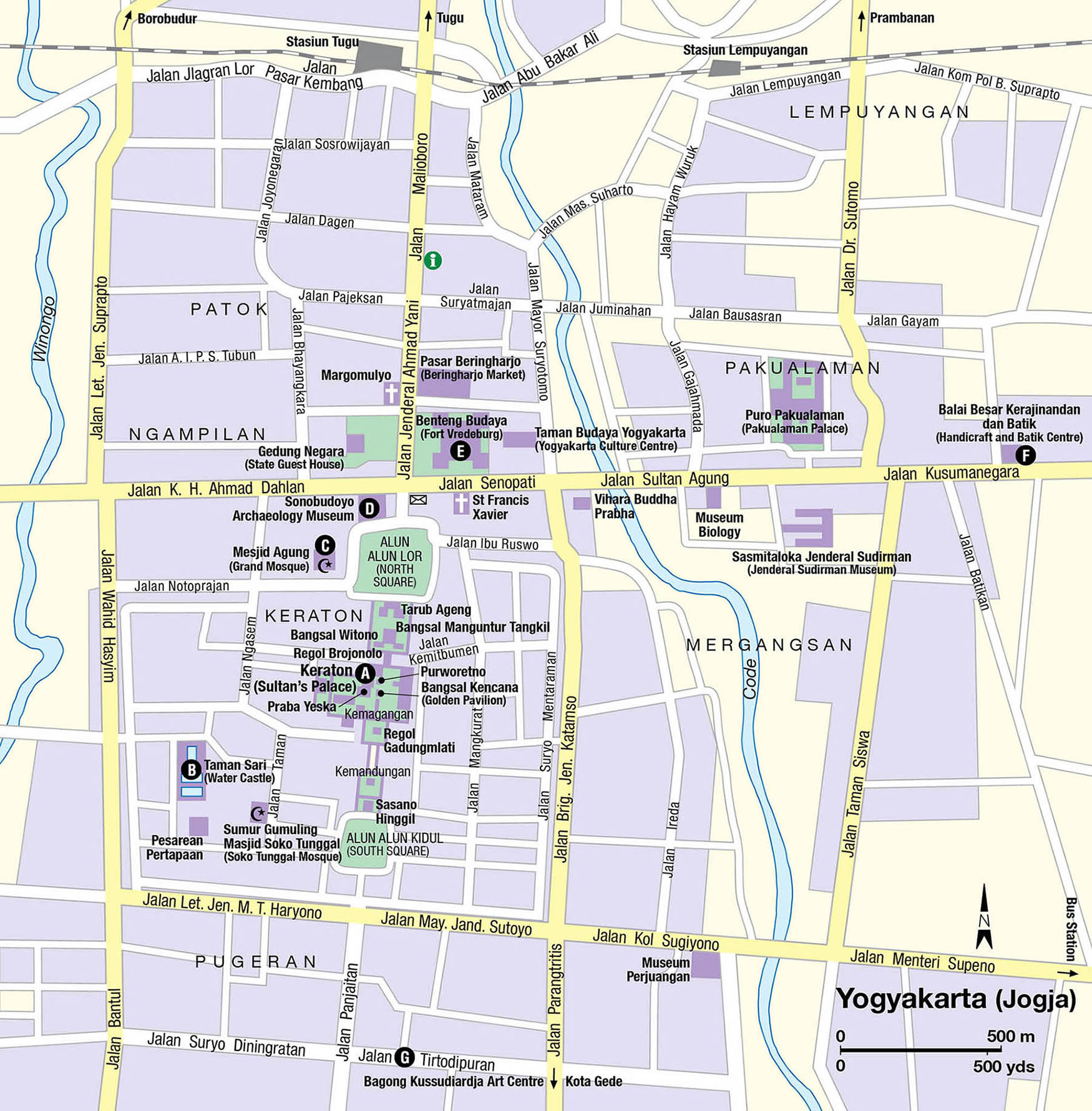

Sprawling Yogyakarta (Jogja) 9 [map] is situated at the very core of an ancient region known as Mataram, site of the first great Central Javanese empires. From the 8th to the early 10th century, this fertile plain was ruled by a succession of Indianised kings – the builders of Borobudur, Prambanan and dozens of other elaborate stone monuments. Around AD 900, these rulers suddenly and inexplicably shifted their capital to East Java, and for more than six centuries, Mataram was deserted.

At the end of the 16th century, the area was revived by a new Islamic power based at Kota Gede, east of present-day Jogja. This second Mataram dynasty was founded around 1575 by King Panembahan Senopati.

Making traditional batik, Yogyakarta.

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

The Yogyakarta and Surakarta (Solo) sultanates came into being in 1755 when the Dutch – fearful of Mataram’s power – split the kingdom into two parts, further dividing each sultanate into two separate entities to dilute their influence. The present sultan of Yogyakarta is descended from one of two Yogyakarta royal families, hence there are two palaces in Jogja. From the original Surakarta line, there are also two families and two palaces, Kasunanan and Mangkunegaran, both in Solo.

The Yogyakarta court was twice invaded by foreigners for failure to comply with colonial instructions – once by the Dutch in 1810 and again by the British in 1812. Later, it was swept into the Great Java War (1825–30), led by the charismatic crown prince of the ruling family, Pangeran Diponegoro.

A coat of arms at Surakarta’s Keraton Kasunanan.

Alamy

In more recent times, Jogja served as the capital of the troubled Indonesian republic for four long years during the fight against the Dutch, from 1945 until 1949. This was a time of extraordinary social ferment. Six million refugees, more than a million young fighters and an enlightened young sultan (Hamengkubuwono IX) transformed the venerable court city into a hotbed of revolutionary idealism. Rewarded for its efforts by the new Indonesian government, Jogja was awarded Special Province status and enjoys the same privileges as the capital city, Jakarta.

A pavilion in the Keraton grounds.

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

The Sultan’s Palace

Today, it is Jogja’s cultural attractions that travellers come to see – ancient temples, palaces, batik, gamelan, dances and wayang puppet performances. Growing in popularity are nature-related activities. The city is a mere hour by plane from Jakarta or 9 hours by the Bima Express train; from Bali, it is 1.5 hours by air or 12 hours by bus. Jogja is easy to get around: there are plenty of taxis, public buses and man-powered becak (pedicab). Andong (horse carts) are used both inside the urban areas and in the countryside.

Tip

Every morning at the Keraton, a classical Javanese court dance, gamelan music, leather or wooden puppet show or poetry recital is held.

The first stop is the Keraton A [map] (Sultan’s Palace; Sat–Thu 8am–1.30pm; Fri 8am–noon), a two-centuries-old palace complex that stands at the heart of the city. According to traditional cosmological beliefs, the Yogyanese ruler is literally the ‘navel’ or central ‘spike’ of the universe, anchoring the temporal world and communicating with the mystical realm of powerful deities. In this scheme of things, the Keraton is both the capital of the kingdom and the hub of the cosmos, bringing the two together through the application of certain elaborate design principles.

The palace houses not only the sultan and his family, but also the dynastic regalia (pusaka), private meditation and ceremonial chambers, a magnificent throne hall, several audience and performance pavilions, a mosque, an immense royal garden, stables, barracks, an armaments foundry and two expansive parade grounds planted with sacred banyan trees – all laid out in a carefully conceived complex of walled compounds, narrow lanes and massive gateways, and bounded by a fortified outer wall measuring 2km (1.5 miles) on every side.

Construction of the Keraton began in 1755 and continued for almost 40 years, throughout the long reign of Hamengkubuwono I. Structurally, very little has been added since his death in 1792. Today, only the innermost compound is considered the Keraton proper, while the maze of lanes and lesser compounds, the mosque and the two vast squares, have been integrated into the city. Long sections of the outermost wall (benteng) remain, and many of the residences inside are still owned and occupied by members of the royal family.

To step within the massive inner walls is to enter a patrician world of grace and elegance. In the first half of the 20th century, the interior was remodelled along European lines, incorporating Italian marble, cast-iron columns, crystal chandeliers and rococo furnishings into a classical Javanese setting. The ‘Golden Pavilion’ or Bangsal Kencana (central throne hall) is its most striking feature – a pendopo or open pavilion consisting of an ornate sloping roof supported at the centre by four massive wooden columns.

There is much more to see within the Keraton, including the Keraton and Royal Carriage Museums, ancient gamelan sets, and two great kala-head gateways.

Puro Pakualam

About 2km (1.2 miles) east of the Keraton is Jogja’s ‘second palace’, Puro Pakualam. In an attempt to stabilise uprisings in Central Java and counterbalance the strength of Sultan Hamengkubuwono I, in 1812 then-Lieutenant Governor-General Thomas Stamford Raffles created a principality within the Yogyakarta sultanate and awarded it to one of the sultan’s sons, Prince Notokusumo. After becoming Paku Alam I, the prince constructed this palace, which is now the official residence of Prince Paku Alam IX and a museum (Tue, Thu and Sun 9.30am–2.30pm); performances are held here too.

Taman Sari

Behind the Keraton stand the ruins of the royal pleasure garden, Taman Sari B [map] (daily 8am–2pm). It was constructed over many years, beginning in 1758 by Hamengkubuwono I and then abruptly abandoned after his death. Dutch representatives to the sultan’s court marvelled at its large artificial lake, underground and underwater passageways, meditation retreats, a series of sunken bathing pools and an imposing mansion of European design.

The ruins of the mansion, named Water Castle by the Dutch, occupy high ground at the northern end of the huge Taman Sari complex, overlooking a colony of batik painters. The crumbling walls and a massive gate are all that remain of the building. A tunnel behind the castle leads to a complex of three restored bathing pools, Umbul Bindangun. The large central pool was designed for the use of queens, concubines and princesses, while the small southernmost pool was reserved for the sultan.

Wayang kulit shadow-puppet play at Sonobudoyo Archaeological Museum.

Alamy

Further south, tucked amid a crowded kampung (village), lies Pesarean Pertapaan, an interesting royal retreat reached by passing through an ornate archway west of the bathing area, then following a winding path to the left. The main structure, a small Chinese-style temple with a forecourt and galleries, is said to be where the sultan and his sons meditated for seven days and nights at a time.

The most remarkable structure at Taman Sari is the Sumur Gumuling (circular well), a mesjid (mosque) with a well as its centrepiece. Folklore says the secret tunnels found there (now collapsed) led to the sea where the sultan could commune with Ratu Kidul, the powerful Goddess of the South Sea, to whom all Mataram rulers had been promised in marriage by the dynasty’s founder and from whom they are said to derive their mystical powers. Access is by an underground passageway, whose entrance lies to the west of the Water Castle. The ‘well’ is in fact a sunken atrium, with circular galleries facing onto a small, round pool.

Tip

The best way to explore Jogja is by becak, a three-wheeled man-powered pedicab, or andong (horse cart). Confirm the fare upfront, then enjoy the ride through scenic backstreets.

Jalan Malioboro

Jogja’s main thoroughfare, Jalan Malioboro, begins in front of the royal audience pavilion, at the front of the palace, and ends at a tugu (monument) dedicated to the guardian serpent spirit Kyai Jaga some 2km (1.25 miles) to the north. Jalan Malioboro derives its name from the Sanskrit words malya bhara, meaning ‘garland bearing’, as the royal processional route was always adorned with bouquets during ceremonial occasions.

Today, Jalan Malioboro is primarily a shopping district, though it is also an area of historical and cultural interest. Begin at the northern town square (alun-alun) and stroll up the street, stopping first at the Mesjid Agung C [map] (Grand Mosque), built in 1773, and notice the two fenced-off banyan trees standing on either side of the road in the centre of the square. They symbolise the balance of opposing forces within the Javanese kingdom.

The extraordinary Sumur Gumuling mosque.

Paul Hessels

Nearby, on the northwestern side of the square, is Sonobudoyo Archaeology Museum D [map] (Tue–Thu 8am–2pm, Fri 8–11am, Sat 8am–1pm). Opened in 1935 by the Java Institute, a cultural foundation of wealthy Javanese and Dutch art patrons, today the museum houses important collections of prehistoric artefacts, Hindu-Buddhist bronzes, wayang puppets, dance costumes and traditional Javanese weapons.

Proceed northwards from the square through the gates and out across Jogja’s main intersection. Immediately ahead on the right stands the old Dutch garrison, Benteng Budaya E [map] (Fort Vredeburg; tel: 0274-586 934; Tue–Thu 8.30am–2pm, Fri 8.30–11am, Sat 8.30am–noon), a museum and cultural centre complete with exhibition and performance halls. Opposite, on the left, stands the State Guest House. It was first the Dutch resident’s mansion and, during the revolution, was also used as the presidential palace. Further along on the right, past the fort, is the huge central market, Pasar Beringharjo (9am–4pm), a rabbit warren of small stalls selling everything from fresh fruits and vegetables to batik, ‘antiques’ and hardware. Bargain hard here.

Back out on Malioboro, both sides of the street are lined with handicraft shops selling a great range of batik, leather goods, baskets, tortoise shell, jewellery and endless knick-knacks. At dusk (4–10pm) the sidewalks explode into an incredible street market of handicraft stalls and food and drink stands. Taste-test some of the traditional snacks such as onde-onde (rice flour balls filled with sweet mung bean paste), lumpia (spring rolls), klepon (green-coloured balls filled with palm sugar) or steamed coconut-coated putu.

Performing arts

Of the many art forms, wayang kulit or shadow-puppet play lies closest to the heart of the Central Javanese. All-night performances for selamatan ritual feasts, weddings or ceremonies occur regularly, often in village compounds. In addition to weekly wayang kulit plays at the Keraton, there is an 8-hour presentation on the second Saturday of every month at the Sasano Hinggil (daily 9am–5pm), near the Keraton. Sonobudoyo Archaeological Museum (Jalan Trikora No. 6; tel: 0274-376 775) holds wayang kulit shows daily except Sunday (8–10pm, closed the night before public holidays; camera fee). Dance and music performances, both traditional and contemporary, as well as changing visual art exhibitions, are held at Taman Budaya Yogyakarta (Jalan Sriwedari No.1; tel: 0274-523 512). Check the programme on arrival to see what is currently on offer.

Getting around by rickshaw.

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

Court dances are also taught outside the Keraton at a number of private schools and government art academies in the city. The performances within the Keraton itself should not be missed, but also check out Bagong Kussudiardja Art Centre (Kembaran Rt. 04 Rw. 21 No. 148 Tamantirto, Kasihan, Bantul, in southern Jogja; tel: 0274-41 4404; www.psbk.or.id), a large performing arts complex dedicated to creating new works within the framework of classical music, dance and theatre. Free monthly performances are open to the public.

Perhaps the ultimate in Javanese dance spectaculars is the Ramayana Sendratari Ballet. A modernised version (the lengthy dialogue in old Javanese has been cut) of the lavish wayang orang dance-drama, the entire epic (four episodes, one per night 7.30–9.30pm) is presented on four clear nights on and around the full moon from May to October. The elegant 9th-century Roro Jonggrang temple at Prambanan (for more information, click here) is the backdrop. There is also an indoor theatre at Prambanan where performances are held during the rainy season.

Batik town

Jogja’s most famous handicraft is still batik, now a Unesco Cultural Heritage icon. Visit the Balai Besar Kerajinandan dan Batik F [map] (Handicraft and Batik Centre) on Jalan Kusumanegara. An individually guided tour costs nothing, and is an excellent introduction to the craft’s painstaking manufacturing process, as well as to the staggering variety of patterns and colours to be found throughout Java. Batik courses are taught here and at other centres.

Batik cloth is produced and sold all over Jogja, but especially in the south of the city on Jalan Tirtodipuran G [map], a street with more than 25 batik workshops and showrooms, most of which are happy to let visitors observe production. Many of the city’s better-known artists, and a number of aspiring ones, also produce batik paintings made with the same resist-dye method, but specifically designed for framing and hanging. For lower-quality souvenir batik cloths and clothing go to Pasar Beringharjo or Mirota Batik, both on Jalan Malioboro.

Tip

One of the best batik courses in Jogja is at Brahma Tirta Sari Studio and Gallery. Not only does it teach the process of batik, it also explains the philosophical meanings behind the traditional patterns (www.brahmatirtasari.org).

Kota Gede gateway.

Gunkarta Gunawan Kartapranata

Kota Gede

Long before Yogyakarta was established, Kota Gede ), 4km (2.5 miles) southeast of Jogja, was founded in 1575 by Sultan Panembahan Senopati as the first capital of the Mataram Empire, where it remained until his successor moved it to Kerta. During its golden years, Kota Gede attracted a myriad of wealthy traders, including Arab and Dutch, who built mansions in exceptional architectural styles.

A pleasant way to arrive is by andong (horse-drawn carriage), about a 20-minute ride from Jalan Malioboro. Now known for its silversmiths, it is an interesting place to stroll around and imagine how it must have been in its heyday, while shopping for jewellery. Accommodation is available in some of the historic buildings, and there is also a restaurant.

About 500 metres (yards) behind the pasar (traditional market) is the Kota Gede Royal Cemetery (Mon 10am–noon, Fri 1.30pm–4pm) dating back to Mataram times. Javanese attire is required to enter to see the graves of Senopati and other important figures, which can be ‘rented’ at the desk where men guard the cemetery. Behind the cemetery is the oldest mosque in the Jogja area and across the street from the cemetery is a traditional Javanese house. While in the area, you may like to visit Monggo Chocolate Factory (Jalan Dalem KG III/978-RT 043 RW 10, Kelurahan Purbayan Kotagede; tel: 0274-710 2202; 8am–5pm daily) to see ‘Belgian’ chocolate being made, using Indonesia cacao of course.

Parangtritis beach.

Alamy

Beaches, caving and climbing

The Indian Ocean is less than an hour’s drive south of central Yogyakarta. Parangtritis ! [map], a wonderful stretch of black sand backed by towering bluffs, is both a popular recreation spot and a place of worship, where the legendary Ratu Kidul, Queen of the South Seas, is said to live. The rip tides are dangerous here, so swimming is forbidden. Nearby is the sacred Parangkusumo beach. Every year on 30 Rajab of the Javanese calendar (ask a local to check for you), a ceremony called Labuhan Alit is held to commemorate the coronation of the Yogyakarta Sultan and offerings are given to Ratu Kidul. The beaches can be done in a day trip from Jogja, but basic lodgings are available if you prefer to stay the night. There are great sunsets on Parangtritis hill, east of the beach.

Twenty kilometres (12 miles) southwest of Jogja via Bantul city are Samas and Pandansimo beaches. Both with the same stormy shores as Parangtritis, Samas is home to a village-run sea turtle conservation project, and Pandansimo is a Javanese pilgrimage site. For swimming beaches, some with white sand, head 60km (40 miles) southeast of Jogja to Baron, Krakal, Kukup, Sepanjang, Drini, Sundak, Ngandong, Siung, Wedi Ombo, Sandang or Ngrenehan. While all are excellent choices for a day of relaxation away from the city’s traffic, Ngrenehan is the best place to have a swim and enjoy some freshly caught fish cooked to order. At Ngobaran beach, 5 minutes from Ngrenehan by car, is Kejawen Hindu temple, built in 2005.

North of the beaches rises the Gunung Sewu mountain range, a length of karst limestone hills perforated by caves. Only a few have been explored, but with the cooperation of villagers who have developed homestays as part of a community project, two have been sufficiently explored by a local caving group to allow novices to participate in the adrenalin rush. The first, Jomblang, requires a vertical rappel down an inclined wall where there is a surprising subterranean forest, fed by the sun and rainfall entering through an enormous, gaping hole at the entrance. Connected to Jomblang by a horizontal corridor is Grubug, a much riskier descent. A river flowing into Grubug is raftable in the rainy season. Nearby, on Siung beach, enormous limestone walls prove popular with cliff climbers. A paragliding jamboree is held in this area when the winds are favourable, March–April.

North of Jogja is volatile Gunung Merapi, popular with climbers until its violent eruption in late 2010. Trekkers and birdwatchers now head to safer environs, for example Gunung Merbabu further north. From Kopeng on its southern flank to Kenteng Songo, one of its two peaks, takes between 8 and 10 hours. The drive there via the Selo Pass affords fabulous volcano views.

Fact

Highly volatile 2,923-metre (9,550ft) Gunung Merapi erupted in 2010, killing at least 300 people and displacing half a million. In 2004 the ‘danger zone’ was declared a national park, but efforts to relocate inhabitants failed because of spiritual beliefs about the mountain. Merapi’s national park status is now being challenged in court. The most recent eruption took place in spring 2014, thankfully without any fatalities.

Traditional batik at the Brahama Tirta Sari Studio in Yogyakarta.

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

Handicrafts around Jogja

The villages around Jogja specialise in handmade crafts, many of which are exported abroad and are the area’s second-largest revenue earner after tourism. Shopping in the villages where the items are made means the craftsmen – not a middleman – reap the benefits with profits going back into the local area, and shoppers get a look at real life in the countryside. South of Jogja are Kasongan and Panjangrejo, which make earthenware pottery; Kota Gede is known for its delicate filigree silverwork; Manding produces leather bags, belts, shoes and jackets; wooden masks and other woodcarvings are found in Sendangsari-Krebet and Patuk; and wayang puppets and hand-forged ceremonial keris blades are specialities of Imogiri.

For authentic keris (ceremonial daggers; for more information, click here) – not the tourist variety sold at souvenir shops – Empu Sungkowo (keris maker) Harum Brodjo (Gatak, Sumberagung, Moyudan, Sleman; tel: 81-2273 1372) is a master craftsman. It takes two months to finish one dagger. You must make an appointment to visit him.

Java’s ancient past

For the Central Javanese, the candi (ancient stone monuments) are tangible evidence of the great energy and artistry of their ancestors. For the foreign visitor, communion with one of these 1,000-year-old shrines provides an opportunity to ponder the achievements of a magnificent culture.

A great deal of effort has been expended since 1900 to excavate, reconstruct and restore their reliefs, study their iconography and decipher their inscriptions. Still, little more than the most basic symbolism of these structures is known, and even their chronology is in doubt. What is known is that they are among the most technically accomplished structures produced in ancient times, and that the awe inspired by their presence has formed a substantial part of their message.

Intricate detail at Borobudur, the work of some 30,000 craftsmen.

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

Borobudur and the Dieng Plateau

If your driver takes the scenic route through villages instead of the congested highway, a leisurely one-hour drive across riverbeds and rice fields leads to the steps of fabled Borobudur @ [map], 40km (25 miles) northwest of Jogja (daily 6am–5pm; licensed guides available), a Unesco World Heritage Site. Allow yourself a minimum of two hours to tour the temple, though you could easily spend half a day here. This huge mandala, the world’s largest Buddhist monument, was built sometime during the relatively short Sailendra dynasty between AD 778 and AD 856 – 300 years before Angkor Wat and 200 years before Notre-Dame. Yet, within little more than a century of its completion, Borobudur and the other structures in Central Java were mysteriously abandoned. At about this time, too, neighbouring Gunung Merapi erupted violently, covering Borobudur in volcanic ash and debris, concealing it for centuries.

Borobudur lay hidden in the jungle for centuries.

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

The rediscovery of Borobudur

The story of Borobudur’s ‘rediscovery’ began in 1814, when the British governor of Java, Thomas Stamford Raffles (who later founded Singapore in 1819), visited Semarang and heard rumours of ‘a mountain of Buddhist sculptures in stone’ near Magelang. Raffles dispatched his military engineer, H.C.C. Cornelius, to investigate. Cornelius found a hillock overgrown with trees, but curiously scattered with hundreds of andesite blocks.

For two months, Raffles directed a massive clearing operation, removing vegetation and layers of earth, until it became clear that an elaborate structure lay beneath. He dug no further, for fear of damaging the unknown monument. In the years that followed, Borobudur was laid bare and subsequently suffered almost a century of decay, plunder and abuse; thousands of stones were ‘borrowed’ by villagers and priceless sculptures ended up as decorations in the homes of the rich and powerful.

In 1896, the Dutch gave away eight cartloads of Borobudur souvenirs to visiting King Chulalongkorn of Siam, including 30 relief panels, five Buddha statues, two lions and a guardian sculpture. Many of these and other irreplaceable works of Indo-Javanese art ended up in private collections, and now reside in museums around the world.

Borobudur’s restoration

In 1900, the Dutch government responded to cries of outrage from within its own ranks and established a committee for the restoration of Borobudur. The huge task was accomplished between 1907 and 1911 by a Dutch military engineer with a keen interest in Javanese antiquities.

At this time, Borobudur was discovered to be a fragile mantle of stone blocks that had been built upon a natural mound of earth. Rainwater was seeping through the stone mantle and eroding the soft foundation from within, while mineral salts were collecting on the monument’s surface, where they acted in conjunction with sun, wind, rain and fungus to destroy it. Grandiose plans for a permanent restoration were never realised, due to the intervention of two world wars and an economic depression.

During the 1950s and 1960s, it became increasingly evident that Borobudur was structurally endangered. Unesco was called to direct a rescue operation. Technical assistance and financing became available, and the project officially got under way in 1975. The scale of the project was spectacular. It took nine long years to dismantle, catalogue, photograph, clean, treat and reassemble a total of 1,300,232 stone blocks. Each stone had to be individually inspected, scrubbed and chemically treated before being replaced. In addition, a new infrastructure of reinforced concrete, tar, asphalt, epoxy and tin was constructed to support the entire monument, and a system of drainage pipes installed to prevent further seepage.

In the end, the work was completed at a cost of US$25 million, more than three times the original estimate. It is unlikely that the full import of Borobudur as a religious monument will ever be known. An estimated 30,000 stone-cutters and sculptors, 15,000 labourers and thousands more masons worked to build the original monument. At a time when the entire population of Central Java numbered less than one million, this represented perhaps 10 percent of the available workforce to a single effort.

Individual dagobas, mini-stupas, at Borobudur.

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

Spiritual significance

Seen from the air, Borobudur forms a mandala, a geometric aid for meditation. Seen from a distance on the ground, Borobudur is a stupa, a model of the cosmos in three vertical parts: a square base supporting a hemispheric body and a crowning spire. The traditional pilgrimage route approaches from the east, and ascends the terraced monument, circumambulating each terrace clockwise in succession to see how every relief and carving contributes to the whole.

There were originally 10 levels at Borobudur, each falling within one of the three divisions of the Mahayana Buddhist universe: khamadhatu, the lower spheres of human life; rupadhatu, the middle sphere of ‘form’; and arupadhatu, the higher sphere of detachment from the world. The lowest gallery of reliefs, now covered, depicts the delights of this world and the damnations of the next.

The next five levels (the processional terrace and four concentric galleries) show in their reliefs (beginning at the eastern staircase and going around each gallery clockwise) the life of Prince Siddhartha on his way to becoming the Buddha, scenes from the Jataka folk tales about his previous incarnations, and the life of the Bodhisattva Sudhana (from the Gandavyuha). These tales are illustrated in stone by a parade of commoners, princes, musicians, dancing girls and saints, with many interesting ethnographic details about daily life in ancient Java. Placed in niches above the galleries are 432 stone Buddhas, each displaying one of five mudra or hand positions, alternately calling upon the earth as witness and embodying charity, meditation, fearlessness and reason.

Above the square galleries, three circular terraces support 72 perforated dagobas (miniature stupas), which are unique in Buddhist art. Most contain a statue of the meditating Dhyani Buddha. Two statues have been left uncovered to gaze over the nearby Menoreh Mountains, where a series of knobs and knolls is said to represent Gunadharma, the temple’s divine architect. These three terraces are, in fact, transitional steps leading to the 10th and highest level, the realm of formlessness and abstraction (arupadhatu), embodied in the huge crowning stupa.

Before leaving the park, have a look at two museums near the exit gate. One houses stones, Buddha images and other pieces from the original structure. The other houses an outrigger ship built to replicate vessels seen on the reliefs. The ship undertook an expedition to Madagascar in 2003–4, recreating the trade route that might have been used when Borobudur was constructed almost two millennia ago. The museum is well presented and the fully reconstructed ship is magnificent.

Every year, thousands of Buddhists arrive from all over Asia to walk in procession from nearby Mendut temple to Borobudur in celebration of Waisak (date changes annually), the holiest day of the year for Buddhists.

Buddha at Candi Mendut.

Alamy

Pawon and Mendut

Two smaller, subsidiary candi lie along a straight line directly east of Borobudur. The closer of the two is tiny Candi Pawon (meaning ‘kitchen’ or ‘crematorium’; daily 6am–sunset), situated in a shady clearing 1.7km (1 mile) from Borobudur’s main entrance. It is often referred to as Borobudur’s ‘porch temple’ because of its proximity, and may well have been the last stop on a brick-paved pilgrimage route.

Just 1km (0.6 mile) further east, across the confluence of two holy rivers (the Progo and the Elo), lies beautiful Candi Mendut (daily 6am–5pm; charge). Unlike most other central Javanese monuments, which face east, Mendut opens to the northwest.

The base and both sides of the staircase are decorated with scenes from moralistic fables and folk tales, many of which concern animals. The main body contains superbly carved panels depicting bodhisattva and Buddhist goddesses. These are the largest reliefs found on any Indonesian temple.

The walls of the Candi Mendut antechamber are decorated with money trees and celestial beings, and contain two beautiful panels of a man and a woman amid swarms of playful children. It is thought that these two panels represent child-eating ogres who converted to Buddhism and became protectors instead of devourers.

Tip

Rafting on the Progo River, which originates at Jumprit on Gunung Sindoro northwest of Borobudur, is an exhilarating sport in the rainy season. In February, the lower reaches are apt to flood and are extremely dangerous. However, in the dry season, the mighty tiger becomes a kitten and is gentle enough for beginners.

Mendut contains three of the finest Buddhist statues in the world: a magnificent 3-metre (10ft) tall figure of the seated Sakyamuni Buddha, flanked on his left and right by Bodhisattva Vajrapani and Bodhisattva Avalokitesvara, each about 2.5 metres (8ft) high. The central or Sakyamuni statue symbolises the first sermon of the Buddha at the Deer Park near Benares, India, as shown by the position of his hands (dharmacakra mudra) and by the small relief of a wheel between two deer. The two bodhisattva, or buddhas-to-be, have elected to stay behind in the world to help Buddha’s followers.

Borobudur and Gunung Merapi at sunrise.

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

The Dieng plateau

Around 100km (60 miles) northeast of Borobudur are arguably the oldest temples in Central Java, dating back to the late 7th century. Travel to the Dieng plateau £ [map] via Kledung Pass, between Mounts Sindong and Sumbing, for breathtaking scenery and, in season, to see the tobacco plantations. Eight small temples stand on this 2,000-metre (6,500ft) high isolated plateau that is usually shrouded in mist. The temples are simple in detail, but it is the mysterious location and the close proximity to volcanic activity, brightly coloured sulphur springs and bubbling mud-holes that are of interest. There is an eerie quality to this site, which ancient Javanese felt to be a centre of supernatural powers. The remains of other temples (originally 400 structures stood here) and several wooden pavilions, indicating perhaps a palace or monastery are spread among the sulphur lakes.

The main temples are named after the heroes of the Mahabharata (for more information, click here) and all are Hindu in design. To the east of Candi Bima is the Telaga Warna (Coloured Lake), with fluorescent hues caused by sulphur vents. Close by are meditation caves. A visit to the plateau is a full day trip. Basic accommodation is available, as well as the lovely four-star Gallery Hotel Kresna in nearby Wonosobo. Visit Dieng plateau early before the afternoon clouds roll in.

Ancient temples on the cool heights of the Dieng plateau.

Robert Harding

East of Dieng plateau in the cool mountain air of the Bandungan highlands are the little-visited Gedung Songo $ [map] temples, the most spectacularly situated antiquities in Java. Successors to the candi at Dieng plateau, nine Sivaitic shrines were built by the Sanjaya dynasty in the 8th century and overlook the lofty peaks and verdant valleys of Central Java, but only seven remain. On a clear day three volcanoes and the Dieng massif can be seen from here. Arrive at sunrise and spend the day exploring the temples and inspiring landscape by foot or on horseback and soaking in the hot springs. Also in this area, near Ambarawa, is the wonderful Museum Kereta Api (Railway Museum, Jalan Stasiun No. 1, Ambarawa; tel: 024-354 5382), housing 21 German- and Dutch-built cogwheel locomotives and a restored train station. Rides through the scenic countryside are offered on weekends and holidays. Check timetables on arrival.

East to Prambanan and Surakarta (Solo)

Heading east from Jogja, past the airport, the main Jogja–Solo highway slices across a volcanic plain littered with ancient ruins. These candi are considered by the Javanese of Central Java to be royal mausoleums and the region is known as the Valley of the Kings.

In the centre of the plain, 17km (10 miles) from Jogja, lies Prambanan % [map] (daily 6am–6pm), a Hindu temple complex and a Unesco World Heritage Site. Completed sometime around AD 856 to commemorate a major battle victory, it was deserted within a few years of its completion and eventually collapsed. Preparations for the restoration of the central temple began in 1918, work started in 1937, and it was completed in 1953. Over time, other disasters have brought it harm. In 2006, a 5.9-magnitude earthquake hit Jogja, and 30–40 percent of the complex sustained major damage. Within a week after the earthquake, a rapid assessment mission was organised by the Indonesian government and Unesco to prepare the international emergency assistance to the compound. The majority of the restoration work has been completed, and most of Prambanan is open to the public, but the main temple – which sustained serious structural damage – is closed and may remain so for a few years.

The central courtyard of the main complex contains eight buildings. The three largest are arrayed north to south: the magnificent 47-metre (155ft) tall main Candi Siva Mahadeva is flanked on either side by the slightly smaller shrines Candi Vishnu (to the north) and Candi Brahma (to the south). Standing opposite these, to the east, are three smaller temples that once contained the ‘vehicles’ of each god: Siva’s bull (nandi), Brahma’s gander (hamsa) and Vishnu’s sun-bird (garuda). Of these, only nandi remains. By the northern and southern gates of the central compound are two identical court temples, standing 16 metres (50ft) high.

Candi Siva Mahadeva, the largest of the temples and dedicated to Siva, is also known as Roro Jonggrang (often incorrectly spelled Loro), a folk name sometimes given to the temple complex as a whole. Local legend has it that Roro Jonggrang was a princess wooed by an unwanted suitor. She commanded the man to build a temple in one night, and then frustrated his nearly successful effort by pounding the rice mortar prematurely, announcing the dawn. Enraged, he turned the maiden to stone, and according to the tale, she remains here in the northern chamber of the temple as a statue of Siva’s consort, Durga. In the other three chambers are statues of Agastya, the Divine Teacher’ (facing south); Ganesha, Siva’s elephant-headed son (facing west); and a 3-metre (10ft) Siva (central chamber, facing east).

One aspect of Roro Jonggrang’s appeal is its symmetry and graceful proportions. Another is its wealth of sculptural detail. On the inner walls of the balustrade, beginning from the eastern gate and proceeding clockwise, the wonderfully vital and engrossing tale of the Ramayana is told in bas-relief (and is completed on the balustrade of the Brahma temple).

Prambanan’s beauty and variety demand more than a single visit. One of the most romantic ways to view the temple is by moonlight, during an open-air performance of the Ramayana, staged on full-moon nights between May and October. During the rest of the year, abridged performances of the epic are held in the adjacent Trimurti Theatre.

Prambanan, a Unesco World Heritage Site.

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

Located just 60km (40 miles) northeast of Jogja on the same highway as Prambanan is noble Surakarta ^ [map], also known as Solo, only an hour away by car or train. Start early for a one-day visit or, if time permits, stay longer and enjoy a batik course, gamelan lesson or join one of the many meditation centres on nearby Gunung Lawu. Solo can also be reached by air from Jakarta and Bali. Although larger than Jogja, Solo is more sedate and has certain cultural characteristics that are different from Jogja’s.

Solo’s Keraton Kasunanan

On the banks of the mighty Bengawan Solo, Java’s longest river, stands the Keraton Kasunanan (Sat–Thu 9am–2pm), constructed between 1743 and 1746. As with the Yogyakarta palace, Surakarta’s Keraton defines the centre of the town and the kingdom as well as, metaphysically, the hub of the cosmos. Indeed, the similarities between the two courts, built within 10 years of each other, are striking. Both have a thick outer wall enclosing a network of narrow lanes and smaller compounds, two large squares, a mosque and a central or inner royal residential complex. Perhaps the major difference is that Surakarta has no north–south processional boulevard or pleasure palace.

Enter the Keraton at the east gate and pay a small fee for a guided tour of the museum and the inner sanctum. Here, shaded by groves of leafy trees, between which flit the bare-shouldered abdidalem, or female attendants, is the large throne hall of the Susuhunan, a titular Muslim prince. Most of the original structure was destroyed by a fire in 1985. The inner columns supporting the roof are richly carved and gilded. Crystal chandeliers hang from the rafters, and marble statues, cast-iron columns and Chinese blue-and-white vases line the walkways. Remove your shoes and refrain from taking photographs. Notice the royal meditation tower to one side. If it looks familiar, that is because it is essentially a Dutch windmill without the arms.

The Keraton museum was established in 1963 and contains ancient Hindu-Javanese bronzes, traditional Javanese weapons and three marvellous coaches. The oldest coach – a lumbering, deep-bodied carriage built around 1740 – was a gift from the Dutch East India Company to Pakubuwono II. The museum also displays some remarkable figureheads from the old royal barges, including Kyai Rajamala, a giant of surpassing ugliness, who once adorned the bow of the Susuhunan’s private boat and is said even now to emit a fishy odour when daily offerings are not forthcoming.

Dance and music as high art

After visiting the Keraton, stroll through the narrow lanes outside, and be sure to pay a visit to nearby Sasana Mulya, the music and dance pavilion of the Indonesian Arts High School (STSI), located just to the west of the main (north) palace gate. This is an art school with an illustrious history: it was here that the first musical notation for gamelan was devised at the turn of the 20th century. Visitors are welcome to listen and observe as long as they do it unobtrusively.

Symbolic keris

The richly embellished dagger is not only a form of high art, but a symbol of male masculinity and an essential accessory for every Javanese man.

Neatly tucked into the waistband of the traditional attire of the Indonesian man is the ceremonial dagger, or keris. No longer a weapon of defence, this ornate blade is rather an indication of social ranking and a source of cultural pride. An old Javanese proverb states: ‘Happy is the man who is the owner of a horse, wife, bird and keris.’ In many parts of Java, the keris is considered to be the most important item a man can own.

The traditional keris is a lightweight elongated dagger with a blade that is either straight or wavy, resembling a flame or serpent, coupled with a hilt and sheath. Originally worn for protection and used as a thrusting weapon, today it is an essential part of the groom’s wedding and other ceremonial Javanese attire. So revered is the dagger that a man’s keris can be a substitute in his absence at his own wedding.

Thought to possess a life of its own and endowed with magical powers, the keris is treated with great respect and reverence. There are many keris legends, including stories about wilful and bloodthirsty daggers that are capable of flying, turning into snakes, fathering children and taking human lives.

Stored in a place of honour, treated with perfumed oils and wrapped in silk and velvet, keris are passed down as sacred family heirlooms. Every year on the first day of the Javanese calendar, the Yogyakarta palace pusaka (heirlooms with spiritual powers), which include an assortment of sacred keris, are cleansed with scented water. Believing the objects to be magically endowed, crowds wait outside for the chance of receiving just a drop of the holy water used in the cleaning ritual, while the keris is carried from the palace in a coach.

Crafting the keris

The keris were (and still are) crafted by empu (master craftsmen), esteemed ironworkers imbued with divine status and who were so revered that they once came under the patronage of the court and were often considered members of the royal household.

Before beginning his work, the empu makes offerings, fasts, meditates and asks for divine inspiration. The blade is forged from several layers of nickel and meteoric iron, using a damascening technique, which in turn produces the desired shades of light and dark patterns on the blade, the pamor. This pattern becomes visible after the blade has been polished and treated with citrus juice and arsenic. Each pattern has a name and meaning. Wos wutah (scattered rice grains), for example, represents prosperity.

Keris are distinguished by the number of curves (always uneven) they support. One wave represents god and king, while three, fire and passion. Each of these qualities is believed to have an effect on the life of the owner. If a man is not suitably matched to his keris, it can affect his life in a negative way. The hilt can be plain or carved with a mythical figure – believed to be capable of warding off evil spirits – in wood, bone or ivory and inlaid with precious metals and stones. The scabbard is usually wooden and encased in richly embossed brass, silver or gold.

A keris dagger.

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

Puro Mangkunegaran

About 1km (0.6 mile) to the west and north of the main Keraton Kasunanan is a smaller, more intimate palace of another branch of the royal family. Begun by Mangkunegara II at the end of the 18th century and completed in 1866, the Puro Mangkunegaran is open to the public (Mon–Sat 8am–4pm; Sun 8.30am–1pm).

The Mangkunegaran’s outer pendopo (audience pavilion) is said to be the largest in Java – built of solid teakwood, and jointed and fitted in the traditional manner without nails. Note the brightly painted ceiling with the eight mystical Javanese colours in the centre, highlighted by a flame motif and bordered by symbols of the Javanese zodiac. The gamelan set in the southwest corner of the pendopo is known as Kyai Kanyut Mesem (‘Kyai Kanyut Smiles’). Try to visit the palace on Wednesday mornings at 10am, when it is used to accompany informal dance rehearsals.

The museum is in the ceremonial hall of the palace, directly behind the pendopo, and it mainly houses the private collections of Mangkunegara IV: dance ornaments, topeng (masks), jewellery (including two silver chastity belts), ancient Javanese and Chinese coins, bronze figures and a superb set of keris.

The tympanum of Puro Mangkunagaran palace, Surakarta.

Meursault2004

Tip

The Karimunjawa Marine National Park is 80km (50 miles) off the north coast of Central Java. Until about 10 years ago there was nothing there except for a handful of fishermen and their families. Dive resorts and lodgings are popping up on some of the islands, which have been set aside for tourism development.

Creating batik.

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

Solo’s antiques and batik

Solo, with its sizeable ‘antique industry’, where many dealers collect and restore old European, Javanese and Chinese furniture and bric-a-brac, is excellent for the unhurried shopper who likes to explore out-of-the-way places in the hope of finding hidden treasures. The starting point for any treasure hunt is Pasar Triwindu, just south of the Mangkunegaran palace. Solo is also the home of Indonesia’s largest batik manufacturers, three of whom have showrooms in town with reasonable fixed prices for superb fabrics, shirts and dresses. Many smaller batik shops also line the main streets. To see why Solo calls itself the City of Batik, visit the huge Klewer textile market beside the Grand Mosque and near the Keraton. Just be sure to know what you are doing if making a purchase here – batik can sell for as little as US$1 or as much as US$100 a metre.

As with Jogja, Solo is renowned as a centre for traditional Javanese performing arts. It is one of the best places to see an evening wayang orang dance performance or wayang kulit shadow play, or listen to live gamelan music. Ornately carved leather puppets, contorted wooden masks and even monstrous bronze gongs sold here make highly distinctive gifts. Solo is also a major centre for meditation, and there are a few places that hold yoga courses for foreigners.

Gunung Lawu and beyond

High on the northwest slopes of Gunung Lawu, about 36km (22 miles) east of Solo, are two 15th-century temples. Little is known about these candi except that they were the last ones built before the Javanese kingdoms converted to Islam. The reasoning behind the Mayan pyramid-shaped Candi Suku remains a mystery, as do the stone altars, three of which are in the shape of giant tortoises. Higher up the slope past tea plantations is multi-terraced Candi Ceto, which is unfortunately in very bad repair, with a large lingga pointing west.

Sangiran

Eighteen km (11 miles) north of Solo is Sangiran (Sragen) & [map], where the remains of the 1.5 million-year-old Java Man were first unearthed in 1891 (for more information, click here). An Unesco World Heritage Site, the small Museum Trinil (Mon–Sat 9am–6pm) in nearby Krikilan village unfortunately only holds replicas of Java Man’s skull fragments and jawbone, but there are also mastodon tusks, artefacts from prehistoric settlements and fossils, some of them over a million years old. New discoveries in this area are frequent.

The north coast

Java’s northern coastal ports were once the busiest and richest towns on the island; they served as exporters of agricultural produce from the fertile Javanese hinterland, as builders and outfitters of large spice trading fleets, and as trading entrepôts frequented by merchants from all corners of the globe. Between the 15th and 17th centuries, when Islam was a new and growing force in the archipelago, these ports flourished as political and religious centres.

Beginning to the west, Cirebon * [map] is an intriguing potpourri of Sundanese, Javanese, Chinese, Islamic and European influences. With a small harbour and a sizeable fishing industry, most sites are within walking distance, though a nice way to get around is by becak (pedicab).

Cirebon’s Keraton Kesepuhan.

Alamy

Cirebon’s two major palaces were both built in 1678, giving each of two princes his own court. The Keraton Kesepuhan (belonging to the elder brother) sits on the site of the 15th-century Pakungwati Palace of Cirebon’s earlier Hindu rulers. Javanese in design with a Romanesque archway framed by mystical Chinese rocks, it is a spacious, pillared pendopo furnished with French period pieces. The walls of the Dalem Ageng (ceremonial chamber) behind are inlaid with blue-and-white tiles exhibiting biblical scenes. The adjoining museum has a coach in the shape of a winged and horned elephant grasping a trident in its trunk – a glorious fusion of Javanese, Hindu, Islamic, Persian, Greek and Chinese mythological elements.

Next to the Kesepuhan Palace stands the Mesjid Agung (Grand Mosque), constructed around AD 1500. Its two-tiered meru roof rests on elaborate wooden scaffolding, and the interior contains imported sandstone portals and a teakwood kala-head pulpit. Together with the Demak and Banten mosques, it is one of the oldest remaining landmarks of Islam on Java.

The Keraton Kanoman (palace of the younger brother) is nearby, reached via a busy marketplace. Large banyan trees shade the peaceful courtyard within, and as at Kesepuhan, the furnishings are European and the walls are studded with tiles and porcelain from Holland and China. The museum has a collection of stakes still used to pierce the flesh of Muslim believers on Mohammed’s birthday (seni debus), as well as relics from Cirebon’s past.

Taman Arum Sunyaragi, about 4km (2.5 miles) out of town on the southwestern bypass, was originally built as a fortress in 1702 and used as a base for resistance against the Dutch. It was cast in its present form in 1852 by a Chinese architect to serve as a pleasure palace for Cirebon’s sultans. About 5km (3 miles) north of the city along the main north coast highway sits the hilltop Tomb of Sunan Gunung Jati, a 16th-century Cirebon ruler and one of the nine legendary wali who helped to propagate Islam on Java.

East to Semarang

About 220km (140 miles), a 4-hour drive, east of Cirebon is Pekalongan ( [map], which announces itself on roadside pillars as Kota Batik (Batik City). Quite apart from the many workshops and stores lining its streets, Pekalongan justifies this sobriquet by producing some of the finest and most highly prized batik on Java. The Pekalongan style, like Cirebon’s, is distinctive – a blending of Islamic, Javanese, Chinese and European motifs.

Another 90km (55 miles) and 2 hours to the east, Semarang , [map] rises out across a narrow coastal plain and up onto steep foothills. Known during Islamic times for its skilled shipwrights and abundant supplies of hardwood, it is today the commercial hub and provincial capital of Central Java. The Dutch Church, Gereja Blenduk, on Jalan Suprapto downtown, with its copper-clad dome and Greek cross-floor plan, was consecrated in 1753 and stands at the centre of the 18th-century European commercial district.

Fact

The Javanese alphabet – similar to Sanskrit – has been officially recognised by Unicode, an organisation under Unesco that deals with alphabetic code standards in computers. This means that Javanese literature, which had been accessible to only a few in the past, will now be available to the world at large.

Semarang’s most interesting district is its Kampung Cina (Chinatown) – a grid of narrow lanes tucked away in the city centre, reached by walking due south from the old church from Jalan Suari to Jalan Pekojan. Some old townhouses here retain the distinctive Nanyang style of elaborately carved doors and shutters and delicately wrought iron balustrades.

A market in Semarang.

Alamy

Half a dozen colourful Chinese temples and clan houses cluster in the space of a few blocks, the largest and oldest of which is on tiny Gang Lombok (turn right by the bridge from Jalan Pekojan). This is the Thay Kak Sie temple, built in 1772, which houses more than a dozen major deities. Those with time and an interest in things Chinese should visit Gedung Batu, Ming Admiral Cheng Ho’s grotto on the western outskirts of town. Cheng Ho arrived in Java in 1405 and is credited with helping to spread Islam.

Demak and the teakwood towns

From Semarang, there are several towns to the east that may be visited as day trips. During the early 16th century, a Muslim kingdom centred on Demak ⁄ [map] was the undisputed nonpareil among Java’s coastal states; now, only the mosque remains. The city has become a place of pilgrimage – seven visits here is equal to a single pilgrimage to Mecca. The introduction of Islam to Java is credited to Sunan Kalijaga, a spiritual adviser to the Demak royal court, who used wayang kulit puppet shows to teach the illiterate masses about the new religion. His grave lies 2km (1.25 miles) southeast of the city. Another focal point is Demak’s Mesjid Besar (Grand Mosque), considered the oldest and holiest mosque in Java. Built in 1466, its architecture combines Hindu and Arabic elements.

Neighbouring Kudus is renowned for beautiful hand-carved teakwood houses that grace the narrow lanes surrounding the Kauman area along its early 16th-century mosque and Muslim quarter. Kudus is also known as ‘Kota Kretek’, or clove cigarette city, as several kretek companies are found here.

Jepara, 35km (20 miles) north of Kudus, has long been known for its teakwood carvings, catering to strong demand for finely detailed panels depicting scenes from the Ramayana and other Hindu-Javanese tales.