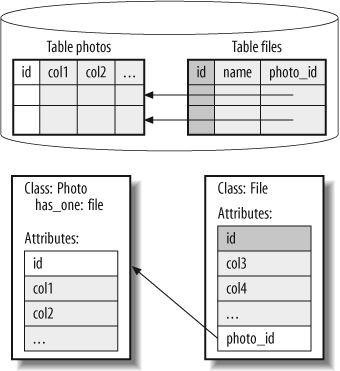

The simplest database relationship is the one-to-one relationship. With Active Record, you can implement one-to-one relationships with either belongs_to or has_one. You decide whether to use belongs_to or has_one based on where the foreign key resides. The class associated to the table with the primary key uses belongs_to, and the other uses has_one. Figure 3-3 shows a has_one relationship.

Let's take a simple example. Hypothetically, you could have decided to implement photos and files in separate tables. If you put a foreign key called photo_id into the files table, you would have this Active Record Photo class:

class Photo < ActiveRecord::Base has_one :file ... end

has_one is identical to belongs_to with respect to metaprogramming. For example, adding either has_one :photo or belongs_to :photo to Slide would add the photo attribute to Slide. We really have no need for adding an extra table to manage a file, so let's move on to the next relationship.

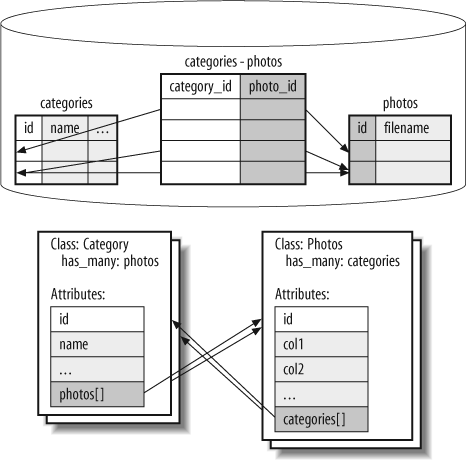

Many-to-many relationships are more complex than the three relationships shown so far, because these relationships require an additional table in the database. Rather than relying on a single foreign key column, you'll need a relationship table. Each row of a relationship table expresses a relationship with foreign keys, but has no other data. Figure 3-4 shows our relationship table.

Figure 3-4. A has_and_belongs_to_many association builds a many-to-many relationship through a join table

Photo Share requires a many-to-many relationship between Photo and Category. A category can hold many photos, and the same photo can fit into more than one category. As always, you'll start with the database. You'll need to create a table called categories to hold all categories. You'll also need a relationship table. The Active Record naming convention for the relationship table is classes1_classes2, with the classes in alphabetical order, so you need to generate a migration for the categories table:

ruby script/generate model Category

This generation step creates a migration containing the model table but not the relationship table. This migration will be a little different. Each photo should be in a category. For our migration, create a default category called All, and place each photo into that category. Edit your migration, and make it look like this:

class CreateCategories < ActiveRecord::Migration

def self.up

create_table "categories" do |t|

t.column "name", :string

t.column "parent_id", :integer

end

create_table("categories_photos", :id=>false) do |t|

t.column "category_id", :integer

t.column "photo_id", :integer

end

Category.new do |category|

category.name = "All"

Photo.find(:all).each do |photo|

photo.categories << category

photo.save

end

end

end

def self.down

drop_table "categories"

drop_table "categories_photos"

end

endThat code is simple enough. The new migration creates two tables: one for categories and one as a join table to manage relationships between our categories and photos. categories is not a model table, so it needs no id. Because we don't want an id column on our join table, we used the parameter :id => false when we created categories_photos. But we're not ready to run the migration until we've created our model objects and defined the relationships between photos and categories. You can't run the migration yet, though. There's no model class for photos, and no relationship between Photo and Category.

Category needs a many-to-many relationship, with the exceedingly verbose Ruby method has_and_belongs_to_many :photos:

class Category < ActiveRecord::Base has_and_belongs_to_many :photos end

You'll also need to add a many-to-many relationship to the Photo class:

class Photo < ActiveRecord::Base validates_presence_of :filename has_many :slides has_and_belongs_to_many :categories end

This code adds the categories collection to Photo, and the photos collection to Category. Now, you can run the migration. Type:

rake migrate

You can verify that it worked in the console. From the console, type:

all = Category.find :first

all.photos.each {|photo| puts photo.filename}You still get a full view of what's going on with categories. Once again, you need some data to illustrate what's going on. Add the following to the end of photos_data.sql:

insert into categories values (1, 'All', null); insert into categories values (2, 'People', 1); insert into categories values (3, 'Animals', 1); insert into categories values (4, 'Places', 1); insert into categories values (5, 'Things', 1); insert into categories values (6, 'Friends', 2); insert into categories values (7, 'Family', 2); insert into categories_photos values (4, 1); insert into categories_photos values (3, 2); insert into categories_photos values (3, 3); insert into categories_photos values (4, 4); insert into categories_photos values (5, 5); insert into categories_photos values (3, 6); insert into categories_photos values (2, 7); insert into categories_photos values (4, 8); insert into categories_photos values (4, 9); insert into categories_photos values (4, 7);

Now, you can see how categories are working inside the console:

>> category = Category.find_by_name "Animals"

...

>> category.photos.each {|photo| puts photo.filename}

camel.jpg

cat_and_candles.jpg

polar_bear.jpg

>> photo.filename = "cat.jpg"

=> "cat.jpg"As expected, you get an array called photos on category that's filled with photos that are associated in the join table categories_photos. Let's add a photo:

>> photo.filename = "cat.jpg" ... >> photo.save => true >> category.photos << photo ... >> category.save

Look a little closer at this statement: category.photos << photo. (It adds a photo to category.photos.) But the save is changing neither the photos nor the categories table. It's actually adding a row to the categories_photos table. This type of relationship is the only instance in which an Active Record class does not map directly to the rows and columns of a database table. The methods and attributes added by the has_and_belongs_to_many method are identical to those added by has_many and are shown in Table 3-2.

You might wonder whether it's possible to create a Rails model from the categories_photos table. As of Rails 1.0, you couldn't do such a thing. Now, with new join models

in Rails 1.1, it's easy. You can use has_many and belongs_to with the through parameter. For example, you could easily decide to map slides in this way:

class Slideshow < ActiveRecord::Base has_many :photos :through => :slides end

This example creates database tables, through migrations or other means, for photos, slideshows, and slides. The relationship table also serves as a relationship table, and a first class model. The structure in the example is slightly different from a typical join table. The primary differences are these:

The

Slideis a first class model.You can add attributes to

Slide.You can use

:throughwithhas_many,belongs_to, andhas_and_belongs_to_many.

The :through relationship makes it possible to build much more sophisticated relationships, allowing you to identify and tag each relationship with additional data, as required.

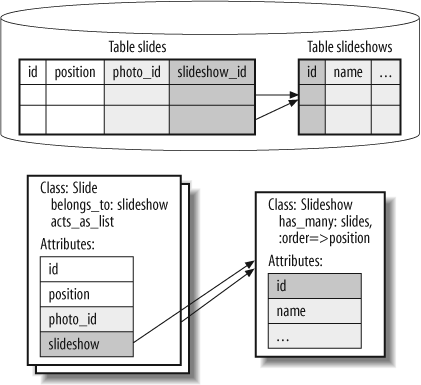

Active Record has three special relationships that let you explicitly model lists, trees, and nested sets: acts_as_list, acts_as_tree, and acts_as_nested_set, respectively. We'll look at the two relationships required by Photo Share in this chapter: acts_as_list and acts_as_tree. acts_as_list lets you express items as an ordered list and also provides methods to move items around in the hierarchy. Figure 3-5 shows the mapping. In Photo Share, we'll use acts_as_list to model a slideshow, which is an ordered list of slides. Later, we'll use acts_as_tree to manage our nested categories.

First, let's create the slideshow. We want users to be able to move slides up and down in a show. We'll use the existing slides and add the Active Record relationship acts_as_list:

class Slide < ActiveRecord::Base belongs_to :slideshow acts_as_list :scope => "slideshow_id" belongs_to :photo end

This example builds a list of slides that comprise a slideshow. belongs_to is a one-to-many relationship, imposing structure. acts_as_list is a helper relationship, imposing order and introducing behavior. To Active Record, each relationship is independent. The Slide model has a belongs_to relationship with both Slideshow and Photo parents. You use the :scope parameter to tell Active Record which items belong in the list. In this case, we want the list to contain all slides related to a slideshow, so set the :scope parameter to :slideshow_id.

To capture ordering, Active Record uses a position attribute by default. Because you have a position column in the database, you don't need to do anything more to the slides to support the list. However, you'll want the array of slides to be fetched and displayed in the right order, so make one small change to Slideshow:

class Slideshow < ActiveRecord::Base has_many :slides, :order => :position end

We're ready to use the list. You can use methods added by acts_as_list to change the order of slides in the slideshow, and to indicate which items are first and last:

>>show = Slideshow.find 1... >>show.slides.each {|slide| puts slide.photo.filename}cat_and_candles.jpg hut.jpg mosaic.jpg polar_bear.jpg police.jpg sleeping_dog.jpg stairs.jpg balboa_park.jpg camel.jpg >>show = Slideshow.find 1=> #<Slideshow:0x3901778 @attributes={"name"=>"Interesting pictures", "id"=>"1", "created_at"=>"2006-05-11 14:57:06"}> >>show.slides.first.photo.filename=> "cat_and_candles.jpg" >>show.slides.first.move_to_bottom=> true >>show.slides.last.photo.filename=> "camel.jpg" >>show.reload=> #<Slideshow:0x3901778 @slides=nil, @attributes={"name"=>"Interesting pictures ", "id"=>"1", "created_at"=>"2006-05-11 14:57:06"}> >>show.slides.last.photo.filename=> "cat_and_candles.jpg" >>

By convention, positions start at 1 and are sequentially numbered through the end of the list. Position 1 is the top, and the biggest number is the bottom. You can move any item higher or lower, move items to the top or bottom, create items in any position, and get relative items in the list, as in Table 3-3. Keep in mind that moving something higher means making the position smaller, so you should think of the position as a priority. Higher positions mean higher priorities, so they'll be closer to the front of the list.

Table 3-3 shows all the methods added by the acts_as_list relationship. Keep in mind that you'll use acts_as_list on objects that already have a belongs_to relationship, so you'll also get the methods and attributes provided by belongs_to. You'll also inherit the methods from array, so slideshow.slides[1] and slideshow.slides.first are both legal.

Table 3-3. Metaprogramming features for acts_as_list

|

Added feature—methods |

Description |

|---|---|

|

|

Increments the position attribute of this list element:

|

|

|

Decrement the position attribute of this list element:

|

|

|

Return the previous item in the list. Higher means closer to the front, or closer to index 1, as in priority:

|

|

|

Return the next item in the list. Lower means closer to the back, or farther from index 1, as in priority:

|

|

|

Test whether an object has been added to a list:

|

|

|

Insert the current item at a given position. Default is position 1:

|

|

|

Return

|

|

|

Return

|

|

move_higher |

Move this item toward index 1:

|

|

|

Move this item away from index 1:

|

|

|

Move this item to index 1:

|

|

|

Make this item the last in the list:

|

|

|

Remove this item from the list:

|

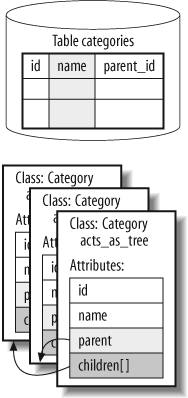

Let's think about the most complex relationship: nested categories. you could implement categories by adding belongs_to :category and has_many :categories to the Category class. The code would not be easy to read because a category would have an instance variable called category (for the parent) and another instance variable called categories for the children. What would be better are instance variables called parent and children, but you'd be forced to override Active Record naming conventions and to write much more code.

This arrangement is common enough that Active Record has the acts_as_tree

relationship, shown in Figure 3-6. As you would expect, acts_as_tree requires a foreign key called parent_id by default. If you use the name parent_id, Active Record discovers and uses that foreign key to organize the tree structure. As always, if you need to override this name, you can do so. Each node of the tree points to its parent, and the root of the tree is null.

Figure 3-6. The acts_as_tree relationship is recursive, with an entity (Category) acting as both parent and children

You've already got a Category class and a database table behind it with a parent_id. Let's let Active Record manage the category tree:

class Category < ActiveRecord::Base has_and_belongs_to_many :photos acts_as_tree end

If you'd like, you can order the children with :order modifier as we did in the favorites example, but you don't have to. The tree is ready to use as is. You can already work with the tree from within the console:

>> root = Category.find_by_name 'All'

...

>> puts root.children.map {|child| child.name}.join(", ")

People, Animals, Places, Things

...

>> puts root.children[0].children.map {|child| child.name}.join(", ")

Friends, Family

...

>> Category.find_by_name('Family').parent.name

=> "People"The children are dependent objects of the parents, so if you delete a parent, you'll delete the children too. Otherwise, what you've created is identical to a has_many relationship and a belongs_to relationship on category. Table 3-4 shows the methods and attributes added by the acts_as_tree relationship.

Table 3-4. Metaprogramming for acts_as_tree

|

Added feature |

Description |

|---|---|

|

Methods | |

|

All methods from |

A tree will have all of the methods of a

|

|

Attributes | |

|

|

|

|

|

An array of children:

|