…The Whites of Their Eyes. The Battle of Bunker Hill.

The Army and the Nation

The Army serves the Nation and defends the Constitution, as it has done for nearly 230 years. The Army has had enormous impact on the course of events throughout that time. This chapter provides a brief description of the Army’s role in our Nation’s history and of the environment the Army operates in today. This chapter also shows the Army’s place as a department of the Executive Branch of the federal government.

Section I - A Short History of the US Army

Colonial Times to the Civil War

The World Wars and Containment

Post-Vietnam and the Volunteer Army

Section II - The Operational Environment

For more information on Army history, see the Center of Military History (CMH) homepage at www.army.mil/cmh-pg.

Much of Section I can also be found in CMH’s 225 Years of Service: The US Army 1775- 2000 and American Military History from the Center of Military History’s Army Historical Series.

For more information on the operational environment, see FM 3-0, Operations. For more information on Army Transformation see the Army homepage at www.army.mil or Army Knowledge Online.

For more information on the US Constitution and our American system of government, see Ben’s Guide to the US Government at bensguide.gpo.gov, the House of Representatives homepage at www.house.gov, or the Federal Government information website at www.firstgov.gov.

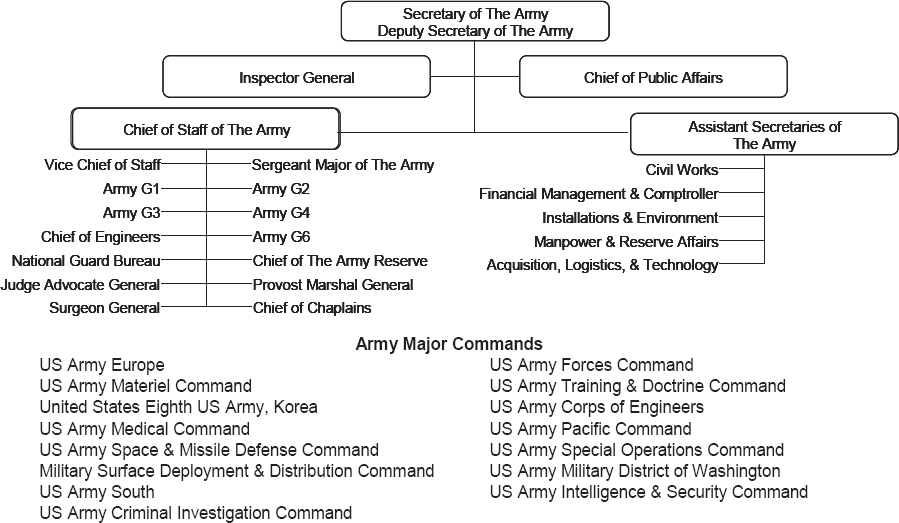

For more information on the Department of the Army organization and missions, see FM 1, The Army, AR 10-5, Headquarters, Department of the Army, and DA PAM 10-1, Organization of the United States Army and the Army Homepage.

SECTION I – A SHORT HISTORY OF THE US ARMY

2-1. The Army’s institutional culture is fundamentally historical in nature. The Army cherishes its past, especially its combat history, and nourishes its institutional memory through ceremony and custom. Our formations preserve their unit histories and proudly display them in unit crests, unit patches, and regimental mottoes. Such traditions reinforce esprit de corps and the distinctiveness of the profession. Our history of past battles bonds and sustains units and soldiers. History reminds soldiers of who they are, of the cause they serve, and of their ties to soldiers who have gone before them. An understanding of what has happened in the past can, in many cases, help a soldier solve problems in the present.

Those who do not remember the past are condemned to repeat it.

George Santayana

COLONIAL TIMES TO THE CIVIL WAR

2-2. The oldest part of our Army, the Army National Guard, traces its heritage to the early European colonists in America. In December 1636, the Massachusetts Bay Colony organized America’s first militia regiments, some of which still serve today in the Army National Guard. Those first colonists and the regiments they formed were primarily made up from colonists who came from England, who brought with them many traditions, including the distrust of a standing army inherited from the English Civil War of the 17th century.

2-3. The colonists used the militia system of defense, requiring all males of military age (which varied as years went by) to serve when called, to provide their own weapons and to attend periodic musters. Theirs was a reliance on citizen-soldiers who served in time of need to assist in the colony’s defense. The various colonies (later states) organized and disbanded units as needed to face emergencies as they arose. Throughout our Nation’s history, volunteer citizen-soldiers have stepped forward to fill in the ranks and get the job done.

2-4. In 1754, George Washington, then 22 years old, led Virginia militiamen in a fight against French regulars at the beginning of the French and Indian War. On one side of the war were the British and American colonists with Indian allies versus the French and their Indian allies. At stake was whether the colonies could continue to expand westward or be limited to the eastern seaboard of the continent. This war would determine who would control North America, the French or the British and American colonists. Such groups as Rogers’ Rangers won fame with their abilities and successes. England won the war and assumed control over the area east of the Mississippi—a vast empire in itself.

2-5. In 1763, the British king decreed that most of the newly acquired territory was off-limits to new colonization and reserved for the use of the native American Indians. The American colonies saw this as complete disregard for what they saw as their right to use the western territories as they saw fit. The following year, Britain imposed the first in a series of taxes designed to pay the cost of British forces stationed in America. The colonists objected to these new taxes. The Billeting Act of 1765 required the Americans to quarter and support British troops. But it was the Stamp Act of that year that most infuriated the colonists. The Stamp Act required that a stamp be affixed to nearly all published materials and official documents in the colonies, as was the case in Great Britain, to produce revenue required for the defense of the colonies.

2-6. Patrick Henry and the Virginia legislature denounced the Stamp Act as “Taxation without Representation.” Americans broke into tax offices and burned the stamps. The level of opposition astonished the British, who thought the Stamp Act was an even, fair way of producing the revenue needed to pay for the defense of the colonies. In the next few years, additional taxes imposed upon other goods further angered Americans. Emotions ran high in Boston where tax officials were occasionally mistreated, causing the British to station two regiments there, which only agitated Americans even more, prompting a number of violent incidents.

Crispus Attucks in the Boston Massacre

On the evening of March 5, 1770, a barber’s apprentice chided a British soldier for allegedly walking away without paying for his haircut. The soldier struck him and news of the offense spread quickly. Groups of angry citizens gathered in various places around town.

A group of men, led by the towering figure of Crispus Attucks, went to the customs house and began taunting the lone British guard there. Seven other soldiers soon came to his support. Attucks was a man who had escaped from slavery and became a sailor to maintain his freedom. He also was a man of some leadership ability. He and a growing crowd confronted the soldiers. In some accounts Attucks struck a British soldier but others say there was no such provocation. In any event, the British fired and Attucks lay dead, struck by two bullets. Samuel Gray, James Caldwell, Samuel Maverick and Patrick Carr also died instantly or in the following days and six others were wounded. Citizens immediately demanded the withdrawal of British troops. The deaths of these men "effected in a moment what 17 months of petition and discussion had failed to accomplish."

The town’s response was significant. The bodies of the slain men lay in state. For the funeral service, shops closed, bells rang, and thousands of citizens from all walks of life formed a long procession, six people deep, to the Old Granary Burial Ground where the bodies were committed to a common grave. Until the signing of the Declaration of Independence, Boston commemorated their deaths on March 5, "Crispus Attucks Day."

2-7. The Declaration of Independence of 4 July 1776 is rightly associated with the birth of our Nation, but the revolution had already been under way for over a year. On 19 April 1775 at Lexington Green, 70 Massachusetts citizen-soldiers stood their ground and refused to allow a British regiment through to destroy a weapons cache in Concord. Without orders, someone on one of the sides fired “the shot heard ‘round the world.” The British fired and charged, killing eight of the Massachusetts soldiers in what began eight years of war but ended with an independent Nation that one day would become the beacon of freedom for uncounted millions around the world. Those first days of our Army and the Republic it served were difficult times. We lost many battles, but won just enough to hang on and maintain the resolve to continue the fight.

2-8. The United States Army began 14 June 1775, when the Continental Congress adopted the New England army besieging Boston as an American Army. The next day Congress selected George Washington to command the first Continental Army: “Resolved, that a General be appointed to command all the continental forces, raised, or to be raised, for the defence of American liberty.” This resolution of the Second Continental Congress established the beginnings of the United States Army as we know it today. Those early days were tough and the British roughly handled the Army. Yet the Battle of Bunker Hill on 17 June 1775 showed the patriots that they could stand up to British regulars.

…The Whites of Their Eyes. The Battle of Bunker Hill.

New York

2-9. In one of the first major actions of the war, General Washington defended New York against a far more mobile British force on Long Island, whose evident intent was to seize New York. The patriots were preparing defenses around New York City and expected an attack. But Washington was desperate for information on British intentions and finally resorted to sending a spy to reconnoiter the enemy positions. Captain Nathan Hale volunteered for the mission.

2-10. After landing on Long Island’s northern shore, Captain Hale moved toward New York. He soon discovered that the British had already begun their attack against the Continental Army. Though the immediate purpose of his mission was negated, Hale continued to try and obtain information of value to the patriots’ cause. Perhaps betrayed by a kinsman, perhaps just unlucky, Captain Hale was captured on 21 September 1776 with incriminating notes of British dispositions. He was brought before General Howe, the British commander. Captain Hale admitted his spying and without a trial, Howe ordered him to be hanged the following morning. Nathan Hale went bravely to his death, knowing he would be an example to his fellow patriots. His last words were, “I only regret that I have but one life to lose for my country.”

2-11. Despite Captain Hale’s bravery, the Americans lost New York to the British and withdrew to New Jersey and then Pennsylvania. General Washington knew that the Nation needed a victory to keep up its spirit and with many soldiers near the end of their enlistment, knew such a victory must come sooner than later. Those were the conditions when Washington decided to attack the Hessian garrison of Trenton, New Jersey. Sailors turned soldiers of Glover’s Regiment from Marblehead, Maine ferried the little force of 2,400 across the icy Delaware on Christmas, 1776. After marching nine miles through heavy snowfall, they charged into the town early the next morning, taking the Hessians utterly by surprise. In 90 minutes it was over and the Army had won a victory to keep the fires of liberty alive for awhile longer. Even though more defeats on the field of battle were ahead, our people, our soldiers and our leaders never lost heart.

These are the times that try men’s souls: The summer soldier and the sunshine patriot will, in this crisis, shrink from the service of their country; but he that stands it NOW deserves the love and thanks of man and woman. Tyranny, like hell, is not easily conquered; yet we have this consolation with us, that the harder the conflict, the more glorious the triumph.

Thomas Paine

Saratoga

2-12. Nearly a year later, the Battles of Saratoga again tested the determination of the patriots. The British had intended to seize Albany, New York by simultaneous advances from Canada and New York City along the Hudson River in order to divide the colonies along that vital waterway, with a third axis from Oswego along the Mohawk Valley. The British attack from New York never materialized, instead becoming diverted to Philadelphia. American forces, swelled by many new volunteers from the state militias, were able to mass against the British coming south from Canada. In a series of battles in September and October 1777, America won its first major victory—a pivotal event in the war. It showed the world that America remained unbowed and determined to win and led to active assistance from the French that complicated the war for the British. Ultimately, the British had to contend with America, France, Spain, and the Netherlands.

The Marquis de Lafayette–Patron of Liberty

Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette was born into French nobility in 1757. After service in the French army, Lafayette became interested in the cause of American freedom. He desired to provide actual assistance and not only sent money to America but also offered his services to the American Congress in 1776. Since official French policy at the time was to remain neutral, Lafayette went secretly to America. In July 1777, Congress appointed him a major general, though stipulated he would have to serve at his own expense—Lafayette received no pay.

After taking part in several battles in which he demonstrated both his bravery and his skill in combat, Congress appointed Lafayette to command an invasion of Canada. Unknown to him, Lafayette’s appointment was wrapped up in a strange conspiracy known as the Conway Cabal. A group of officers had decided that the conquest of Canada was more important than loyalty to America or to General Washington. Lafayette, who was intensely loyal to General Washington, was appointed simply to provide the pretense of legitimacy to the affair. He soon saw the plot for what it was. After determining the mission had insufficient resources, he succeeded in canceling the ill-advised attack entirely. Lafayette continued to lead well in battle elsewhere.

Soon after France allied herself to America, Lafayette decided he could serve the American cause best by returning to France in order to strengthen the relationship and enhance cooperation between the Nations. Lafayette provided a full report on the situation in America and persuasively argued for complete support of the Americans, including ground troops. He returned to America with many French soldiers. The assistance of France was essential to winning the Revolutionary War. With the Marquis de Lafayette, General Washington won the Battle of Yorktown in 1781.

Lafayette continued his support long after the Revolution, though he returned to his native France. He returned to the United States in 1825 for a yearlong visit and was greeted by thunderous applause wherever he went. Americans still remembered his important role in winning freedom. Lafayette died in 1834 and was buried in Paris. An American flag flies over his grave.

Valley Forge

2-13. Our soldiers endured the harsh winter of 1777-1778 at Valley Forge but learned how to make war under the tutelage of a Prussian drillmaster named Friedrich Wilhelm “Baron” von Steuben. The self-styled “Baron” (he wasn’t really a baron, but the soldiers didn’t care) took the ragtag remnants of two years of hard campaigning and turned them into a force that could stand against the might of the British empire. Von Steuben carried out the program during the late winter and early spring of 1778. He taught the Continental Army a simplified but effective version of the drill formations and movements of European armies, proper care of equipment, and the use of the bayonet, a weapon in which British superiority had previously been marked. He attempted to consolidate the understrength regiments and companies and organized light infantry companies as the elite force of the Army. He impressed upon officers their responsibility for taking care of the soldiers and taught NCOs how to train and lead those soldiers.

I would cherish those dear, ragged Continentals, whose patience will be the admiration of future ages, and glory in bleeding with them.

Colonel John Laurens

2-14. Von Steuben never lost sight of the difference between the American citizen soldier and the European professional. He realized that American soldiers often had to be told why they did things before they would do them well. He applied this philosophy in his training program. After Valley Forge, Continentals would fight on equal terms with British regulars in the open field. Much of what von Steuben taught our soldiers is still in use today. After his training took effect, the Continental Army became the equal of the British forces. Nonetheless, operations in the northern states degenerated into a stalemate that lasted to the end of the war.

Von Steuben Instructs Soldiers at Valley Forge, 1778

War in the South

2-15. The Revolutionary War after 1777 was mainly fought in the southern states. There it was a war between patriots and Tories—Americans who remained loyal to the crown and were recruited by the British to fight the rebels. As such, it was more a civil war than not, and neighbors and brothers fought each other in engagements that became increasingly vicious and merciless. They fought as much to protect their homes and families as for the future of the new nation.

2-16. On the patriot side, much of the combat power existed in bands of guerrillas, employing hit and run tactics that helped whittle away British strength and interrupt supplies. Francis Marion, the “Swamp Fox,” led one of these partisan groups. What he lacked in numbers he made up for in audacity and thorough knowledge of the terrain, his soldiers, and his enemy. Over the course of three years he harassed the enemy, cut his communications, and caused the British to divert many soldiers to eliminating him.

2-17. The Tories were usually more organized, often led by a British officer, and fought more in line with existing British tactical doctrine. But some of the Tory units took up the practice of burning houses and destroying crops to deny them to the patriots. It had the effect of pushing the southern population, much of whom had been loyal to the Crown, into the American cause. One of these Tory units was under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Banastre Tarleton. Tarleton was the British commander on the field at the American disaster of the Battle of Waxhaws.

2-18. In May 1780, the British captured Charleston, South Carolina and its garrison, leaving the entire south open to attack. The prospects of American victory had never looked worse. But General Washington appointed Nathanael Greene as commander of the Southern Army. Greene began to wear down the British by leading them on a six-month chase through remote areas of the Carolinas and Virginia.

2-19. Greene never won a battle, but maintained constant pressure on the enemy with local guerrilla groups. The British, low on supplies, began stealing from any Americans they encountered, infuriating them. The British recourse to theft and destruction of property turned the local populace against the British. Many had been sympathetic to the Loyalist cause, but no more. The British actions directly resulted in their defeat at the Cowpens on 17 January 1781. Greene’s persistence won back the south as the British abandoned post and city to return to the seacoast where they could maintain unhindered communications.

Cowpens

2-20. Part of Greene’s strategy was to split his Army to cause the British to weaken their forces in pursuit. It worked when the British commander detached Tarleton’s command, reinforced by two regiments of British regulars, to pursue one of the columns of Continentals and militia, commanded by Brigadier General Daniel Morgan. Though untrained in tactics or strategy, Morgan knew his soldiers’ strengths and weaknesses and that of his enemy. He turned to face the British in a field known as Hannah’s Cowpens and won a victory that altered the course of the war.

2-21. Though outnumbered by Tarleton’s force, Morgan chose a low, sparsely wooded hill to defend. He would place most of his his militia in the front, instructing them to fire two shots before withdrawing. Behind these militia troops would be his stalwart Continentals and trusty Virginia militia in the main line and a small cavalry force as his reserve. Morgan intended for the first lines of militiamen to fire at close range to strike down enemy leaders and depart the field as if retreating. Then when the British charged after them, they would run into the main line of Continentals and Virginians. He spent much of the evening before the battle ensuring all his soldiers knew the plan and what was expected of them. He knew each soldier would do his duty.

2-22. Tarleton’s aggressiveness was also something Morgan counted on when the battle began the next morning. As expected, after the militia fired and withdrew, the British closed on the main line of patriots. They attempted to outflank the American right, and a misunderstood order caused the Continentals there to move to the rear. Tarleton thought they were retreating and plunged recklessly after them. But Morgan turned the Continentals about and charged the attacking British. While engaged to the front, the American cavalry and the reformed militia surrounded Tarleton’s force of 1,100 and killed, wounded, or captured all but 50 who barely escaped, including Tarleton himself. This decisive victory seriously reduced the British strength in the south.

Yorktown and Victory

2-23. Soon the British began a withdrawal to Yorktown where they would evacuate part of the force to New York. Instead the French fleet arrived and drove off the outnumbered British vessels that were guarding the Chesapeake Bay. They landed 3,000 more French troops to join the 12,000 Americans and French that had surrounded Yorktown and began a blockade to deny reinforcements or evacuation from Yorktown. The resulting siege ended when the British surrendered on 19 October 1781, the day “the world turned upside down.”

2-24. The victory at Yorktown broke the will of the British to continue the war and ultimately decided it in America’s favor. The Revolutionary War officially ended 3 September 1783 with the signing of a peace treaty in Paris. The British recognized the United States as a free and independent nation and that the US boundaries would be the Mississippi River in the west and the Great Lakes in the north. The area west of the Appalachian Mountains was called the Northwest Territory.

A NEW NATION

2-25. The United States initially were governed by a document called the Articles of Confederation. After a few years Congress called for a convention simply to mend the document’s flaws. But the convention soon decided to write a new instrument, the Constitution. When it was ratified the Constitution left in place a small professional Army supplemented by the militia of all able-bodied males, under strict civilian control. Read more about the Constitutionin Section III.

2-26. Despite the treaty provisions at the end of the Revolutionary War, the British did not evacuate the Northwest Territory. Even so, American Settlers began moving into the territory. The native American Indians in the area believed the land was theirs because of previous treaties and resisted this encroachment. Americans suspected that the British were arming the Indians and perhaps encouraging their resistance. A confederation of tribes led by Chief Little Turtle of the Miami soundly defeated two major Army expeditions sent to protect the American settlers from Indian raids. This caused a crisis of confidence in the effectiveness of the Federal government and of the Constitution itself. President Washington appointed General Anthony Wayne to prepare a force to remove the Indian threat to the settlers if ongoing negotiations failed.

2-27. The negotiations did indeed fail. The US would not ban settlers from moving across the Ohio River and the Indian tribes would not allow such intrusion without a fight. On 11 September 1793, President Washington ordered General Wayne to attack. Wayne built forts deeper and deeper into Indian territory and defeated all attacks against them, severely shaking the Indians’ confidence in their leaders and in their ability to win the struggle. By August 1794, Wayne had offered the remaining tribes a chance to end to the fighting but received no response.

The Road to Fallen Timbers

2-28. Expecting a battle, Wayne made known the Army would attack on 17 August. Realizing that the Indian warriors habitually did not eat on the day they expected combat, Genereal Wayne waited an additional three days believing many of the Indians would leave to seek food. He attacked on 20 August 1794 near Toledo, Ohio, and fought the remaining 800 Indian warriors in a forest that had suffered severe damage from a recent storm, giving the battle its name “Fallen Timbers.” In less than two hours Wayne defeated the Indian force, paving the way for the Treaty of Greenville that secured southern and eastern Ohio and effectively ended British interference in the Northwest Territory.

LEWIS AND CLARK

2-29. The young Nation more than doubled in size in 1803 when it acquired a huge expanse of territory from France in what became known as the Louisiana Purchase. President Jefferson sent the “Corps of Volunteers for North Western Discovery” to explore and assert American authority over the area. Sergeants John Ordway, Nathaniel Pryor and Charles Floyd (and later Sergeant Patrick Gass when Floyd died along the Missouri River) joined two Army officers, Captains Meriwether Lewis and William Clark.

2-30. With a select group of volunteers from the United States Army and civilian life they ventured west towards the Pacific coast. The skill, teamwork, and courage of each soldier contributed significantly to the success of the expedition. When the soldiers finally returned in September 1806 after traveling almost 8,000 miles in under two and a half years, their journey had already captured the admiration and imagination of the American people.

WAR OF 1812

2-31. In the early 1800s Britain and France were at war with each other and desperate for men and materiel. Both belligerents seized American ships at sea but Britain was the chief offender because its Navy had greater command of the seas. The British outrages took two distinct forms. The first was the seizure and forced sale of merchant ships and their cargoes for allegedly violating the British blockade of Europe. The second, more insulting type of outrage was the capture of men from American vessels for forced service in the Royal Navy.

2-32. The seat of anti-British sentiment appeared in the Northwest and the lower Ohio Valley, where frontiersmen had no doubt that their troubles with the Indians in the area were the result of British intrigue. Stories circulated after every Indian raid of British Army muskets and equipment being found on the field. By the year 1812 the westerners were convinced that forcing the British out of Canada would best solve their problems. Then on 1 June 1812, President Madison asked Congress to declare war, which it narrowly did by six votes in the Senate.

2-33. American strategy was simple; conquer Canada and drive British commerce from the seas. But in practice, it became clear that public support for an enterprise was critical to the success of American operations. After a few abortive attempts to invade Canada in which many regional militia units were unwilling to take part, the Army quietly went into winter quarters. Repeated attempts throughout the war to make gains in Canada met with similar misfortune.

2-34. In 1813 American forces attempted to take the western panhandle of Florida and southern Mississippi, then territories of Spain. Defending the area were a few tribes of Indians that had long been difficult to control. Initially poor logistics preparation stymied the small American force of volunteers, but after reorganization and additional reinforcements, they drove the remaining tribes into Spanish–held Florida.

2-35. In 1814 the Army fought its finest engagements of the war. Though strategically the US was frustrated yet again in failing to conquer Canada, time after time the Army fought hard and well against the very best units of the British Empire, many of which were veterans of the war against Napoleon. At Lundy’s Lane, where Sergeant Patrick Gass fought with distinction, Baltimore and Plattsburg, well-trained regulars and volunteers acquitted themselves superbly against what was then believed to be the finest infantry in the world.

2-36. In setbacks like Bladensburg, poor training and poor leadership were the reasons why 5,000 hastily assembled Regulars, militia and naval gunners were swept aside by an inferior British force that then entered and burned Washington. Yet many of these same militia, after two weeks of training, were resolute and inflicted heavy loss on the British in the defense of Baltimore.

2-37. News of the British defeats at Baltimore and at Plattsburg caused the British government to reevaluate its objectives in North America. As a result it redoubled efforts to reach an agreement in peace negotiations that were already underway, ultimately resulting in peace by the Treaty of Ghent on 24 December 1814, two weeks before what was probably the most famous battle of the war.

The Battle of New Orleans

2-38. In late 1814 the British sent 9,000 soldiers to capture New Orleans in order to isolate the Louisiana Territory from the United States. They landed at a shallow lagoon some ten miles east of New Orleans. During an engagement on 23 December 1814, General Andrew Jackson almost succeeded in cutting off an advance detachment of 2,000 British, but after a 3-hour fight in which casualties on both sides were heavy, Jackson was compelled to retire behind fortifications covering New Orleans.

2-39. Opposite the British and behind a ditch stretching from the Mississippi River to a swamp, Jackson prepared the defense with about 3,500 soldiers and another 1,000 in reserve. It was a varied group, composed of the 7th and 44th Infantry Regiments, Major Beale’s New Orleans Sharpshooters, LaCoste and Daquin’s battalions of free African-Americans, the Louisiana militia, a band of Choctaw Indians, the Baratorian pirates, and a battalion of volunteers from the New Orleans aristocracy. To support his defenses, Jackson had assembled more than twenty pieces of artillery, including nine heavy guns on the opposite bank of the Mississippi. He was forced to scour New Orleans for a variety of obsolete and rusty small arms to equip his entire force. Knowing many of these dueling pistols and blunderbusses were nearly useless against British muskets, he shaped the battlefield to his advantage by erecting formidable earthworks, high enough to require scaling ladders for an assault.

2-40. After losing an artillery duel, the British commander decided to launch a frontal assault with 5,400 of his force. On 8 January 1815, waiting patiently behind high banks of earth and cotton bales, the Americans opened a murderous fire, first with artillery and then with small arms. In the area of the main attack the British were decimated and the commanding general killed. The British successor to command, horrified by the losses, ordered a general withdrawal. Over 2,000 British soldiers were killed or wounded as opposed to 13 on the American side.

2-41. Soon after, word came that a peace treaty had been signed on Christmas Eve—two weeks before the battle. The War of 1812 was over, and the Army had kept the Nation free. Although the United States did not conquer Canada (President Jefferson once said it would be “a mere matter of marching”), it did gain new respect abroad and inspired a sense of national pride and confidence. The US Army was recognized as a formidable force.

30 YEARS OF PEACE

2-42. After Wellington’s victory at Waterloo in June 1815, Americans feared there would be another war with Britain. Such fears prompted congress to triple the size of the peacetime regular Army (to 10,000), begin an impressive program of building fortifications along the vulnerable eastern seaboard, and improve the facilities at the US Military Academy at West Point. Because of these efforts, America enjoyed 30 years of relative peace, although sharply punctuated by wars with the Creek and Seminole Nations, the Blackhawks, and other Indian tribes.

2-43. For the first time since von Steuben’s Blue Book, the Army developed written regulations to standardize many aspects of Army operations. The Army Regulations of 1821, written by General Winfield Scott, covered every detail of the soldier’s life such as the hand salute, how to conduct a march, and even how to make a good stew for the company. General Scott was one of the most prolific writers in the Army of the early 19th century. Based on his combat experience in the War of 1812 and other conflicts, he wrote a manual of infantry tactics that was used with minor modification until the Civil War.

2-44. Scott believed that the US Army needed a formal system of tactics to enable it to operate effectively. The tactics of the time, based on the line formation, were a result of the small arms technology of that period. Infantry armed with muskets had an effective range of less than one hundred meters. This fact and the extremely slow rate of fire of the weapons meant that to mass fires required massing soldiers. Soldiers had to operate in tightly packed units. But firepower was really a means to an end. The bayonet charge was the decisive movement and the ability to maintain a tightly packed formation simply assured the attacker would be able to outnumber the defender at the point of attack.

2-45. General Scott also explained the School of the Soldier, providing explicit detail on how a soldier stands, walks and moves, all to most efficiently move large groups of soldiers about the battlefield and to ensure their fire was concentrated where the commander desired it. Scott’s Tactics provides us a distant echo of how our Army trains today. In the School of the Soldier, School of the Company, and the School of the Battalion, we see familiar traces of individual and collective training. It may be said that Winfield Scott turned the US Army into a professional fighting force with the methodical application of standardized training techniques.

2-46. As America grew, western expansion and exploration brought settlers into more frequent conflict with the Indian nations. Much of the regular Army was stationed on the western frontier to try and maintain peace and order. But the expansion was free of European interference, due to the isolation gained by Britain’s naval supremacy that kept the peace at sea. That isolation enforced the Monroe Doctrine and allowed the Army to turn its focus to the west. At times the Army was the buffer between the settlers and the native Americans while at other times it was directed to move the Indian tribes, by force if necessary, from their lands. One such action turned into the Black Hawk War, in which Abraham Lincoln participated as a captain of volunteer infantry.

2-47. From 1821-1830 large numbers of Americans, at the invitation of the Mexican government, moved into the area called Texas. This soon became the focus of a dispute that would lead to war with the United States. The growing numbers of settlers from the United States created suspicion in the Mexican government which then ordered a halt to all immigration and began to reassert its authority in the area. Volunteers from across the United States went to Texas to lend their support.

The Alamo

2-48. In December 1835 Texians (immigrants from the United States) and Tejanos (Hispanic Texans), fighting for independence, seized the towns of San Antonio de Bexar and Goliad and began preparing them as outposts for an expected Mexican counterattack. The volunteers in San Antonio, under the command of Colonel James C. Neill, expertly strengthened the existing fortifications centered on the old mission of the Alamo. After Neill had to leave to attend an illness in his family, Colonel Jim Bowie and Lieutenant Colonel William B. Travis jointly commanded the garrison at the Alamo, fully expecting Colonel Neill to return in a few weeks.

2-49. The Mexican Army under General Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna would not give them that time. Santa Anna arrived outside the Alamo on 23 February 1836 and immediately demanded the surrender of the garrison, who promptly refused by firing a cannon in reply. General Santa Anna prepared for a siege and began pounding the fort with his artillery.

2-50. Travis took over sole command on 24 February 1836 when Colonel Bowie fell seriously ill. He sent a number of messages calling for reinforcements but only 32 more volunteers had arrived by 1 March 1836. By 5 March 1836 only 189 Texians and Tejanos defended the Alamo. Still, they kept the enemy at their distance, sniping at Mexican work parties and gun crews. But on 5 March, even though the siege and bombardment were having effect on the Alamo’s fortifications and defenders, General Santa Anna abruptly decided to assault the fort before dawn the next morning.

2-51. At 0400 on 6 March 1836, Santa Anna began his assault. About 1,800 Mexican soldiers attacked in four columns, but the rifle and cannon fire of the defenders repelled the first two attempts to scale the outer walls. The vast advantage in numbers allowed the Mexican force to continue its attack and succeeded in breaching and scaling the walls on the third try. The Mexican soldiers poured into the Alamo, killing every defender, but suffered over 600 casualties in doing so. It was a very costly Mexican victory that served to rally Texans in subsequent battles.

2-52. After Sam Houston’s decisive victory at San Jacinto the following month, Mexican forces withdrew from Texas. For the next nine years Texas operated as an independent republic although the Mexican government did not recognize it as such. At the same time, Texas was trying to become part of the United States. Their efforts were frustrated for a time over the issue of slavery, but on 1 March 1845 Congress resolved to admit Texas to the Union. Because Mexico had desired to regain control of Texas for itself, she promptly broke off diplomatic relations with the United States and both countries prepared for war. In addition to regulars, volunteers from Texas and Louisiana joined General Zachary Taylor at the Rio Grande where they built a number of fortified positions to pressure Mexico into accepting that river as the international boundary.

WAR WITH MEXICO

2-53. Hostilities began 25 April 1846 near Matamoros and were soon followed by the Battles of Palo Alto and Resaca de la Palma. In these successive battles, the Army fought a defense against a force that was twice as large. The next day, they attacked an entrenched enemy force and drove it from the field. Enlisted soldiers demonstrated their toughness and resiliency, and the officer corps provided skillful leadership, particularly in the use of artillery. Yet these early victories were incomplete because Taylor’s force had no means to cross the Rio Grande in pursuit of the defeated Mexican force. By the time Taylor had brought boats from Point Isabel, the enemy had withdrawn into the interior of Mexico.

2-54. To provide the necessary resources to win the war, Congress authorized an increase of the Regular Army to 15,540 and also authorized the President to call for 50,000 volunteers to serve for one year or the duration of the war. The United States’ objective in the war was to seize all Mexican territory north of the Rio Grande and Gila rivers all the way to the Pacific. This area comprised what we know today as New Mexico, Arizona, California, Nevada, Utah and parts of Colorado and Wyoming. To accomplish this huge task the Army would attack to destroy the Mexican Army’s offensive capability and occupy key points in northern Mexico to obtain favorable terms. In attacks along three axes in northern Mexico, the US Army never lost a battle. But Mexico continued to resist and American leaders concluded that a direct strike at Mexico City was necessary.

2-55. The Army under General Winfield Scott made its first ever major amphibious landing at Vera Cruz on 9 March 1847. While heavily fortified, the city fell within the month and soon the Army was moving west. During the next five months, the Army’s soldiers again displayed fine fighting qualities at Vera Cruz, Cerro Gordo, Churubusco, and Chapultepec. Army officers distinguished themselves as scouts, engineers, staff officers, military governors, and leaders of combat troops. Many of these officers, including Robert E. Lee, Joseph E. Johnston, Thomas J. Jackson, Ulysses S. Grant, and George B. McClellan, would command the armies that would face each other in the American Civil War fourteen years later.

2-56. Ultimately, Mexico capitulated and signed the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo on 2 February 1848. After full ratification on both sides, Mexico recognized the Rio Grande as the boundary of Texas and gave control of New Mexico (including the present states of Arizona, California, New Mexico, Nevada, Utah, and part of Wyoming) to the United States in exchange for $15 million. This addition to the United States and the settlement of the Oregon boundary dispute with Great Britain opened a vast area that would occupy the Army’s attention until the Civil War.

THE CIVIL WAR TO WORLD WAR I

2-57. Slavery had been a bitterly divisive issue among Americans since before the Revolutionary War. By the Presidential election of 1860, a number of political compromises had averted war. Presidential candidate Abraham Lincoln’s platform included that he would not support extending slavery into the western territories. Southerners believed this would give political advantage to the northern states. In addition, Congress had imposed a tax on certain imported manufactured goods in order to protect American industries, most of which were in the north. But it was the issue of the expansion of slavery that most directly led to war.

THE CIVIL WAR

2-58. After American voters elected Lincoln as President, South Carolina seceded from the Union. Other southern states soon followed, though some took a wait and see approach. Virginia, for example, did not secede until after Fort Sumter fell when the President ordered a partial mobilization to suppress the rebellion. The American Civil War had been avoided for many years but began when South Carolina militia forces fired on Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor in April 1861.

2-59. The regular Army at the beginning of the Civil War was tiny in comparison to the task at hand and it was almost totally engaged with peacekeeping on the western frontier. Both the North and the South had to call for volunteers to fight for their respective sides. Initially, many in the North thought it could suppress the rebellion in a short time so the President called for volunteers for a short period of enlistment. The rush to the Colors on both sides following the call for volunteers reflected the country’s tradition of a citizenry ready to spring to arms when the Nation was in danger.

2-60. In overall command at the beginning of the war was General Winfield Scott (the same officer who fought in 1812 and against Mexico and wrote the 1821 regulations). He understood that the defeat of the South would take a long time and the Union would have to attack the Confederacy’s economy. His plan was to conduct a naval blockade of the South to prevent imports and exports, split the Confederacy by seizing the length of the Mississippi, and maintain continuous pressure along the entire front while waiting for the Confederacy to either dissolve from internal dissension or seek peace negotiations. But this strategy would take time, so much so that it was initially ridiculed as the “Anaconda Plan” because of the slow effect it would have. War fever was high and politicians, newspaper editors, and the public wanted action. They thought that if the Federal (Union) forces could simply seize the capital of the Confederacy, the South would just give up.

Early Battles

2-61. The Union defeat at the First Battle of Bull Run showed the need for more thorough preparation and for more soldiers. That realization allowed professional Army officers like Major General George B. McClellan to begin the hard work of transforming volunteers into soldiers. Within months, the Army increased to almost 500,000 men, and it would grow much larger in the ensuing years. Regular Army personnel, West Pointers returning from civilian life, and self-educated citizen-officers all did their part in transforming raw recruits into an effective fighting force.

2-62. Ultimately, the North adopted the essential elements of Scott’s Anaconda Plan and it did, indeed, take time. The four years of bloody warfare that followed cost nearly as many Americans’ lives as in all our other wars combined, before and since. Civil wars, by their nature, are brutal and merciless. Yet, for the common soldier on both sides, there were examples of extraordinary courage, compassion, and fortitude. That they endured is testament to the natural strength of the American soldier.

2-63. The Confederacy had clear disadvantages in comparison to the Union states. The smaller population of the South and the huge disparity in manufacturing capability were the most obvious of these. But these were partially offset, at least initially, by the great skill of southern commanders and the established trade the Confederacy continued with European nations. The South’s greatest advantage was that it simply had to endure to succeed. For the Union to win it would have to conquer the Confederacy or force it to negotiate a truce that included rejoining the Union. This put the northern states on the strategic offensive in order to succeed.

2-64. In its efforts to restore the Union in 1861 and 1862, the Army achieved mixed results. It secured Washington, DC, and the border states, and provided aid and comfort to Union loyalists in West Virginia. In cooperation with the Union Navy, the Army seized key points along the southern coast, including the port of New Orleans, while the Navy conducted an increasingly stronger blockade of the Confederacy. Under such leaders as Major General Ulysses S. Grant, the Army occupied west and central Tennessee and secured almost all of the Mississippi River.

2-65. In the most visible theater of the war, however, the Union Army of the Potomac under a series of commanders made little progress against the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia, commanded by General Robert E. Lee. After victories in the battles of Seven Days and Second Bull Run, Lee invaded Maryland. The Union victory at the Battle of Antietam forced Lee to return to Virginia, although subsequent defeats at Fredericksburg and Chancellorsville brought the Union effort in the East no closer to success than it had been at the start of the war.

Antietam and Emancipation

Lee crossed the Potomac in 1862 for a number of compelling reasons. Primarily he wanted to maintain the initiative in the war. A battle on northern soil would show the people of the Union that it was going to be a long, hard struggle to subdue the Confederacy. Perhaps it would push them to vote more pro-southern politicians into office in the coming election. He also hoped that such an invasion would encourage European support of the Confederacy. Finally, since it was harvest time, he wanted his army to subsist on northern crops.

President Lincoln wanted to prevent any European alliance with the Confederacy. Since the Europeans were opposed to slavery, he thought freeing the slaves would make it politically impossible for European nations to side with the South. Emancipation would also gain the full and continuing support of abolitionists in the North. But issuing an Emancipation Proclamation while Union armies were losing battles might be seen as an act of desperation, rather than one of strength.

The Battle of Antietam on 17 September 1862 was a bloody day on which 6,000 soldiers were killed and 17,000 wounded in a twelve-hour period. In tactical terms, Antietam was a draw. General Lee’s army was severely outnumbered at the outset and his enemy, Major General George McClellan, knew his invasion plan, yet the Confederates still held the field at the end of the day. But the terrible losses Lee sustained meant he could not continue operations on Union territory without risk of complete destruction. Lee’s resulting withdrawal from Maryland was a strategic victory for the Union and provided Lincoln the opportunity to issue the Emancipation Proclamation.

2-66. President Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation on 22 September 1862 freed the slaves in any areas still under Confederate control as of 1 January 1863. This had no real effect until the Union Army took control of those areas, but it expanded the Army’s mission of restoring the Union to include freeing the slaves in the Confederate states. Soon Union armies moving through the South were followed by a fast-growing multitude of African-American refugees, most of them with little means of survival.

2-67. The Army gave food, clothing, and employment to the freedmen, and it provided as many as possible with the means of self-sufficiency, including instruction in reading and writing. African-Americans in the Union Army were among those who achieved literacy. After years of excluding African-Americans, the Army took 180,000 into its ranks. Formed into segregated units under white officers, these free men and former slaves contributed much to the eventual Union victory. One of the notable units was the 54th Massachusetts Regiment, which led an assault on Battery Wagner at Morris Island on 18 July 1863.

The First Medal of Honor Recipient

Congress authorized the creation of the Medal of Honor on 12 July 1862 and on 25 March 1863, Private Jacob Parrott, Company K, 33d Ohio Volunteer Infantry, received the first Medal of Honor ever awarded.

In April 1862 Private Parrott and 23 other volunteers were part of a raid into Georgia to destroy track and bridges on the railroad line between Atlanta and Chattanooga. They penetrated nearly 200 miles south and boarded a train headed north. During a scheduled stop at Big Shanty, Georgia, the group stayed on the train while the engineer, conductor, and the rest of the passengers went to get breakfast. Then the Union soldiers uncoupled the engine, tender and three boxcars from the rest of the train. Most of the men got into the rear car, while the raid leader boarded the engine with Privates Wilson Brown and William Knight, both engineers, and another soldier who acted as fireman. The group steamed out of the station without incident.

The Union soldiers drove the train north but soon the Confederates began to chase them in another locomotive. The raiders tried to burn bridges, but because they were followed so closely were unable to destroy any. Even dropping off some of the train cars along the way did not slow the pursuers. Eventually, they ran out of fuel north of Ringgold, Georgia and the raiders tried to escape on foot. All were captured, including Private Parrott. He returned to the Union after a prisoner exchange in March 1863. For his part in the undercover mission, Private Jacob Parrott became the first recipient of the Medal of Honor, soon followed by other surviving raiders.

Gettysburg

2-68. In June 1863 General Lee decided to invade the North again. He intended to draw the Union Army of the Potomac out of its strong defensive positions guarding Washington, DC, and destroy it on ground of his choosing. At the very least, he intended to disrupt the plans of the Army of the Potomac. Lee led his Army of Northern Virginia into Pennsylvania and the Army of the Potomac followed. They met at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania on 1 July 1863, where Union cavalry had occupied favorable defensive positions on Seminary Ridge west of the town. The cavalry held long enough for infantry and artillery of the Army of the Potomac to begin arriving. But then more Confederate units marched in from the north and outflanked the Union positions. They drove the Union soldiers back through Gettysburg onto Cemetery Ridge and Culp’s Hill east of the town, where the Union line held.

2-69. On 2 July 1863 Lee attacked again, on both the Union right and left. Though poorly coordinated and starting late in the day, it nearly succeeded. On the Union left, resolute soldiers from Maine, New York, Pennsylvania, and Minnesota helped prevent the Confederates from flanking the Union Army. On that day the names Peach Orchard, the Wheatfield, Devil’s Den, and Little Round Top were etched into US Army history.

The 1st Minnesota at Gettysburg

On the second day of the Battle of Gettysburg, the Union III Corps moved forward of the Union lines on Cemetery Ridge to occupy a position about 600 meters to its front. While the position was good, the III Corps was too small to secure its flanks and therefore was vulnerable. This became obvious when two Confederate divisions crashed into the III Corps’ southern flank.

The fighting in the Peach Orchard and the Wheatfield lasted through the afternoon, but ultimately the III Corps was overwhelmed and began streaming back over Cemetery Ridge with the Confederates in close pursuit. If they succeeded in pushing over the ridge they could outflank the Army of the Potomac and defeat it on northern soil, with disastrous consequences to Union morale. Major General Winfield Hancock, seeing the danger, ordered two brigades to Cemetery Ridge to plug the gap left by the retreating III Corps, but it would take time. The only troops in the area were the soldiers of the 1st Minnesota Infantry. Hancock galloped to its commander, Colonel William Colvill, Jr., and pointing at the enemy closing on the ridge told him, “Colonel! Do you see those colors? Take them!” With no hesitation Colvill and his 262 soldiers moved down the slope toward the 1,600 Confederate soldiers.

The 1st Minnesota drove into the enemy, causing confusion and stopping them in their tracks. Though they suffered terrible casualties, the volunteers from Minnesota bought the five minutes needed to move two brigades into position on Cemetery Ridge and so prevented a rout of the Army of the Potomac. At the end, only 47 of the 262 soldiers on the rolls that morning were left standing. This casualty rate of 82% was the highest of any Union regiment in the war.

2-70. On 3 July 1863, the third day of the Battle of Gettysburg, General Lee thought he could still win with one last attack. After an intense artillery preparation about 13,000 Confederate soldiers advanced across a mile of ground swept by Union artillery and small arms fire into the center of the Union line. With the Confederates was Major General George Pickett’s division. The courage of Americans on both sides was never more clearly demonstrated than during Pickett’s Charge. Despite the loss of half the attacking force, the Confederate infantry reached the Union line where infantry and artillery turned them back with crippling losses, effectively ending the battle. During the Battle of Gettysburg, a total of 51,000 Union and Confederate soldiers were killed, wounded or became missing but it was unquestionably a Union victory. Though the war would not end for nearly two more years, Gettysburg gave the Union renewed hope in victory.

2-71. In July 1863 Grant’s triumph at Vicksburg gave the North control of the entire Mississippi River. The capture of Chattanooga, Tennessee, in the fall of 1863 opened the way for an invasion of the Confederate heartland. Appointed commander of all the Union armies, Grant planned not only to annihilate the enemy’s armies but also to destroy the South’s means of supporting them.

Washington, Nov. 21, 1864.

Dear Madam, --

I have been shown in the files of the War Department a statement of the Adjutant General of Massachusetts that you are the mother of five sons who have died gloriously on the field of battle.

I feel how weak and fruitless must be any words of mine which should attempt to beguile you from the grief of a loss so overwhelming. But I cannot refrain from tendering to you the consolation that may be found in the thanks of the Republic that they died to save.

I pray that our Heavenly Father may assuage the anguish of your bereavement, and leave you only the cherished memory of the loved and lost, and the solemn pride that must be yours to have laid so costly a sacrifice upon the altar of freedom.

Yours very sincerely and respectfully,

A. Lincoln

President Lincoln’s letter to Mrs. Lydia Bixby of Boston, Massachusetts

2-72. Grant wore down Lee’s army at the Wilderness, Spotsylvania Court House, and Petersburg during the 1864 and 1865 campaigns. His commander in the West, Major General William T. Sherman, drove through Georgia and the Carolinas, burning crops, tearing up railroads, and otherwise wrecking the economic infrastructure of those regions. “Sherman’s March” showed that victory might be hastened by destroying the enemy’s economic basis for continued resistance and demoralizing his population.

2-73. In March and April 1865 Grant pursued Lee and his Army of Northern Virginia to Appomattox Court House, Virginia. General Lee recognized further bloodshed would not alter the outcome of the war and surrendered his army on 9 April 1865. The Confederate formation under General Joseph Johnston surrendered to General Sherman on 26 April 1865, twelve days after the assassination of President Lincoln. The last major Confederate unit west of the Mississippi gave up on 26 May 1865.

2-74. The bloodiest war in American history was over, slavery was gone, over 600,000 Americans on both sides had died, but the Union was preserved and the South would be rebuilt. The Army’s role in reunifying the nation was not finished with the end of the war. The Army had already established military governments in occupied areas, cracking down on Confederate sympathizers while providing food, schools, and improved sanitation to the destitute. This role continued after the collapse of the Confederacy, when Congress adopted a tough "Reconstruction" policy to restore the Southern states to the Union.

“The Surrender.”

General Lee meets General Grant at Appomattox, 9 April 1865.

2-75. The Army maintained order in the former Confederate states. Keeping watch over local courts, the Army sought to ensure the rights of African-Americans and Union loyalists, a task that became increasingly difficult as support for Reconstruction waned and the occupation forces declined in numbers. At the same time, military governors expedited the South’s physical recovery from the war. Through the Freedmen’s Bureau, the Army provided 21 million rations, operated over fifty hospitals, arranged labor for wages in former plantation areas, and established schools for the freedmen. The Army’s role in Reconstruction ended when the last federal troops withdrew from occupation duties in 1877.

THE WESTERN FRONTIER

2-76. Soon after the Civil War the bulk of the Regular Army returned to its traditional role of frontier constabulary. Early settlers from Europe had been in conflict with native Americans as early as 1622. For over 250 years there were periodic wars and battles as settlers moved west into the wilderness. Conflict often resulted as the Indian nations fought to preserve their way of life while the Army fought to protect settlers, property, and the continued expansion of the United States.

2-77. Army officers negotiated treaties with the Sioux, Cheyenne, and other western tribes and tried to maintain order between the various tribes and the prospectors, hunters, ranchers, and farmers moving west. Native American tribes were pushed off lands they had inhabited for centuries. They fought against the encroachment, periodically raiding settlements, work parties or wagon trains. When hostilities erupted, the Army was usually ordered to force the Indians onto reservations. Campaigns generally took the form of converging columns invading hostile territory in an attempt to bring the enemy to battle. Most of the time, the tribes lacked the numbers or inclination to challenge an Army unit of any size.

The 7th Cavalry at the Little Bighorn

In 1875, the Sioux and Cheyenne left their reservations, infuriated at violations of their sacred lands in the Black Hills. They gathered in Montana with Sitting Bull and vowed to fight. Victories in early 1876 made them confident to continue fighting through the summer. The 7th Cavalry and other units moved to find and destroy hostile encampments and force the Indians back onto their reservations.

On 25 June 1876 Lieutenant Colonel George A. Custer, commanding the 7th Cavalry, learned that a Sioux village was in the valley of the Little Bighorn River in Montana. He expected that the village contained only a few hundred warriors at most and that the Indians would try to slip away from the cavalry as in previous engagments. Custer divided his force of 652 soldiers into four columns to simultaneously attack the northern and southern ends of the village and also block any escape. But the plan did not account for difficult terrain or the fact that the village was much larger than he expected. The village actually contained 1,800 well armed warriors, and they intended to stay and fight.

At about 1500, Major Marcus A. Reno’s element of 175 soldiers began their attack on the southern end of the village. Hundreds of Indian warriors spilled out of the village and routed the cavalrymen. By 1630 the Indians had turned their attention to Custer’s column of 221 soldiers approaching the village from the east. The Indians pushed them back onto a ridge and encircled them. In an hour all of the soldiers in Custer’s group were dead. Though the united Sioux and Cheyenne nations had achieved a great victory, it had aroused the American public who demanded retribution. The boundaries of the reservation were redrawn to exclude the Black Hills and settlers flooded the area. Within a year the Sioux and Cheyenne were defeated.

2-78. The Army contributed in other ways to the development of the West. One Army officer, Captain Richard H. Pratt, established the US Indian Training and Industrial School at Carlisle Barracks, Pennsylvania, to teach Native American youth new skills. At the same time, other soldiers conducted explorations to finish the task of mapping the continent. The surveys from 1867 through 1879 completed the work of Lewis and Clark, while discoveries at Yosemite, Yellowstone, and elsewhere led to the establishment of a system of national parks. Army expeditions explored the newly purchased territory of Alaska. For ten years before the formation of a civilian government, the Army governed the Alaska Territory.

SPANISH-AMERICAN WAR

2-79. As the nineteenth century drew to an end, the Army again served the Nation during the American intervention in Cuba’s war of liberation from Spain in 1898. A US Navy battleship, the USS Maine, anchored in the harbor at Havana, Cuba, mysteriously exploded on the night of 15 February 1898 killing 266 American sailors. Public opinion quickly turned hostile toward Spain and Congress declared war on 25 April 1898. The Army once again struggled to organize, equip, instruct, and care for raw recruits flooding into its training camps. By the end of June 1898 the Army had embarked 17,000 soldiers enroute to attack approximately 200,000 Spanish soldiers occupying Cuba.

The 1st Volunteer Cavalry—“The Rough Riders”—at Kettle Hill near Santiago, Cuba on 1 July 1898.

2-80. The expeditionary force that included Lieutenant Colonel Theodore Roosevelt’s volunteer cavalry regiment began landing in Cuba on 22 June 1898. The Army drove the Spanish from the San Juan Heights overlooking the port of Santiago, causing the enemy ships in the port to flee into the waiting guns of the United States Navy. Other expeditionary forces landed in the Spanish possessions of Puerto Rico and the Philippines, following Commodore George Dewey’s naval victory at the Battle of Manila Bay. With the end of the war and American acquisition of the Philippines, the Army’s task of establishing American authority led to a series of arduous counterguerrilla campaigns to suppress the insurrectos—Filipinos who still fought for independence.

Private Augustus Walley in Cuba

On 24 June 1898 during the Battle of Las Guasimas, Cuba, Major Bell of the 1st Cavalry had gone down with a wound to the leg. Another officer attempted to carry him from the field, but his shattered leg bone broke through the skin, causing so much pain that he had to let Bell down. The fire was so intense that in one plot of ground, fifty feet square, sixteen men were killed or wounded. Still, a fellow American soldier was badly hurt and in need of assistance. Private Augustus Walley of the 10th Cavalry, the “Buffalo Soldiers,” his compassion overcoming self-preservation, ran to help the wounded soldier. He and the officer together dragged Major Bell to safety.

Conspicuous gallantry under fire was not new to Walley. He had received the Medal of Honor while assigned to the 9th Cavalry for his actions on August 16, 1881 in combat against hostile Apaches at the Cuchillo Mountains, New Mexico. During the fight Private Burton’s horse bolted and carried him into enemy fire where Burton fell from his saddle. Assumed dead, the command was given to fall back to another position, but Burton called out for help. Private Walley, under heavy fire went to Private Burton’s assistance and brought him to safety.

Walley was recommended for a second Medal of Honor for his role in saving Major Bell at Las Guasimas. Instead he received a Certificate of Merit for his extraordinary exertion in the preservation of human life. In 1918 Congress upgraded Certificates of Merit to the Distinguished Service Medal and in 1934 to the Distinguished Service Cross.

2-81. The experience of the Spanish-American War, the perception of increased external threats in a shrinking world, and other looming challenges of the new century called for a thorough reform of Army organization, education, and promotion policies. The new Secretary of War, Elihu Root, added an Army War College as the high point of the service’s educational system. He also took steps to replace War Department bureaus and a commanding general with a chief of staff and general staff that could engage in long-range war planning. Also, a new militia act laid the foundation for improved cooperation between the Regular Army and the National Guard. These reforms, as well as some first steps toward joint Army-Navy planning, reflected the emphasis on professionalism, specialization, and organization that characterized the Progressive Era and were in accord with Secretary Root’s conviction that the “real object of having an Army is to prepare for war.” Subsequently, Congress authorized 100,000 as the regular Army strength in 1902.

2-82. After the turn of the century, the Army began to look into the value of aircraft. Balloons used for artillery spotting had already proven their worth in the Civil War. But new developments, the dirigible and the airplane, caught the interest of President Theodore Roosevelt. On 1 August 1907 Captain Charles D. Chandler became the head of the Aeronautical Division of the Signal Corps, newly established to develop all forms of flying. In 1908 the corps ordered a dirigible balloon of the Zeppelin type, then in use in Germany, and contracted with the Wright brothers for an airplane. Despite a crash that destroyed the first model, the Wright plane was delivered in 1909. The inventors then began to teach a few enthusiastic young officers to fly; Army aviation was born.

PANCHO VILLA AND THE PUNITIVE EXPEDITION

2-83. Years of injustice and chafing under dictatorial rule caused the Mexican people to revolt in 1910. The United States attempted to stay out of the affair but was reluctantly drawn into the Mexican Revolution. A number of incidents raised tension between the United States and Mexico, and America began to take sides in the conflict. In May 1916 Pancho Villa’s Mexican rebels killed eighteen American soldiers and civilians in a raid on Columbus, New Mexico. Part of the 13th Cavalry, then garrisoned in Columbus, drove Villa off and hastily pursued, killing about 100 “Villistas” before returning to Columbus.

2-84. In an attempt to bring Villa to justice or destroy his ability to raid the US, President Woodrow Wilson sent Brigadier General John J. Pershing to lead an expedition south of the border in an unsuccessful pursuit of Villa. The Mexican government threatened war over the violation of its territory, causing Wilson to call up 112,000 National Guardsmen and to send most of the Regular Army to the border. But the two nations avoided a larger conflict and America withdrew the punitive expedition.

THE WORLD WARS AND CONTAINMENT

2-85. World War I began in August 1914 after a Bosnian separatist murdered the Archduke Francis Ferdinand of Austria-Hungary and his wife during a visit to Sarajevo. Austria-Hungary demanded that Serbia allow them to investigate the crime but under conditions that Serbia would not accept. Because of numerous alliances and agreements, Austria-Hungary’s subsequent declaration of war on Serbia soon embroiled most of Europe. For nearly three years the United States remained technically neutral, though its trade favored the Allies who controlled the seas. America, with its large immigrant population, was not eager to go to war against any of the nations in Europe. Even after German submarines sank the passenger ships Lusitania and Sussex, the United States refrained from joining the conflict. The war in Western Europe degenerated into a bloody stalemate, nearly destroying an entire generation of young men. Both the western allies and Germany launched offensive after offensive in the hopes of achieving a breakthrough that would end the war but all in vain.

THE UNITED STATES ENTERS WORLD WAR I

2-86. On 23 February 1917 the British turned over to the US Government an intercepted note from the German foreign minister to the German ambassador in Mexico. In the note were instructions to offer Mexico an alliance in the event of war with the United States and promising that Mexico could regain Texas, New Mexico and Arizona. Coupled with Germany’s recent resumption of unrestricted submarine warfare, this was the last provocation America needed. On 2 April 1917 President Wilson asked Congress to declare war on Germany because “the world must be made safe for democracy.”

2-87. A much more professional Army spearheaded American intervention in World War I. After Wilson’s war message in April 1917, Army officers worked with business and government counterparts to mobilize the nation’s resources. Yet enormous difficulties resulted from the huge size of the effort. To meet the need for a massive ground force capable of fighting on the European battlefield, the Army drew on its Civil War expertise and on popular acceptance of a more activist federal government to develop a more efficient system of manpower allocation through conscription.

Lafayette, we are here.

LTC Charles E. Stanton, at the grave of the Marquis de Lafayette

2-88. The 1st Infantry Division reached Paris in time to participate in a Fourth of July parade, raising French spirits at a low point in the war. Ultimately, 8 regular Army divisions, 17 National Guard divisions, and 17 newly organized National Army divisions served in France. The US divisions were twice the size of Allied and German divisions but American soldiers and marines had a lot to learn about trench warfare. At training centers near the front they practiced and received a hint of what lay ahead.

2-89. Though slower to arrive than France and Britain wished, the sight of fresh, eager, and strong American soldiers in great numbers, with millions more available, raised the allies’ spirits and eroded German morale. But the Allies wanted American soldiers sent directly to British and French formations as individual or unit replacements. However, the Commander in Chief of the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF), General John J. Pershing was determined to preserve the independence of the AEF. He would not allow Americans merely to be absorbed into existing British and French units.

2-90. This stance was based not only on national pride but also on President Wilson’s vision that the United States would have to take a more active, leading role in the post-war world. Enabling that role would require a significant role in the war as a distinct fighting force. On occasion Pershing did offer the use of American regiments and in a few instances, even smaller units in the British and French sectors. In fact, two US divisions fought as a corps in the British sector. But Pershing resisted all attempts to get American soldiers sent directly to British and French units as individual replacements.

By early 1918 General Pershing relented somewhat in his policy of not sending Americans directly to the Allies. He provided the infantry regiments of one of the African-American infantry divisions, the 93d, (the US Army was still segregated at the time) directly to the French Army. One of these regiments, the 369th Infantry, was formed from the National Guard’s 15th New York and was in combat longer than any other American regiment in the war.

In May 1918, Privates Henry Johnson and Needham Roberts of the 369th were part of a five-man patrol on duty in a listening post along the front line. The other three soldiers were off-watch and sleeping in a dugout to the rear when a 24-man German raiding party caught the post by surprise with a grenade attack. Both Johnson and Roberts were seriously wounded but fought off the first attack and crawled to their own supply of grenades. Throwing them one after another like baseballs at batting practice, they fought back with explosives as Johnson shouted, "turn out the guard," over and over. Grabbing his rifle, he shot a German soldier and clubbed another. He then saw three enemy soldiers trying to drag Roberts away.

Out of grenades and with his rifle now jammed and broken, Johnson pulled out his knife and attacked the three Germans, killing one. Roberts broke free and continued fighting. Hit by fire, Johnson fell wounded and dazed, but nonetheless took a grenade off a dead enemy soldier and threw it at his attackers. It devastated the remaining enemy and they withdrew leaving their dead and a number of rifles and automatic weapons. When reinforcements arrived, they found the two soldiers laughing and singing. Privates Johnson and Roberts were both peppered with shrapnel and shot several times, but remained in good humor and reportedly saw the experience as a great adventure.

Later promoted to Sergeant, Johnson was the first American in World War I awarded the Croix de Guerre with Palm, France’s highest award for gallantry. On 13 February 2003, Sergeant Henry Johnson received the Distinguished Service Cross posthumously.

2-91. Germany saw the potential of the United States and resolved to defeat the French and British allies before US power could be fully brought into the war. In July 1918 the Germans launched an offensive that carried it nearly to the outskirts of Paris. In the line east of Chateau-Thierry was the 3d Infantry Division, just arrived to try to stem the German advance at the Marne River.

2-92. The division’s infantry regiments were deployed along the south bank of the Marne River with the French 125th Division on its right. Attached to the French division were four companies of the US 28th Division, National Guardsmen from Pennsylvania. As the German attack reached and began crossing the Marne River, the French units were forced to withdraw but did not inform the American Guardsmen. The Keystone soldiers fought against many times their own number, delaying and inflicting heavy losses on the enemy, but ultimately most of the Americans were killed or captured. Nonetheless, their bravery and sacrifice helped make the historic stand of the 3d Division possible.

2-93. The 38th Infantry Regiment soon found itself under attack from three sides and the other regiments of the 3d Division under great enemy pressure, as well. Wave after wave of German infantry crossed the Marne and assailed the front and flanks of the 38th, but the resolute Doughboys held on. When asked by a French commander if his division could hold, Major General Joseph Dickman replied, “Nous resterons la”—We shall remain there. They did, helping to break the German attack and entering into Army history. Two months later the US First Army attacked at St. Mihiel. In the Meuse-Argonne campaign, the AEF contributed to the final Allied drive before the Armistice.

Sergeant Edward Greene at the Marne

Sergeant Greene was a cook for the 3d Division’s Battery F, 10th Field Artillery in July 1918. He was without a mission when his field kitchens were destroyed in the pre-assault bombardment prior to the German attack across the Marne river. Sergeant Greene, without being ordered, began carrying ammunition forward to his battery’s guns.

For several hours while under constant artillery shell fire and enemy observation, he performed his mission until wounded. He had to be ordered to the rear for medical attention. Sergeant Greene received the Distinguished Service Cross.

2-94. World War I was the impetus for many new innovations in weaponry, industry, and medicine. In an attempt to break the stalemate on the Western Front, the Germans used chlorine gas as a weapon in 1915. Not having anticipated the effectiveness of the weapon against unprepared troops, they did not exploit the resulting panic among the Allied soldiers in the affected area. The Allies soon developed defensive measures to mitigate the effects of chemical weapons, though even today they have terrifying potential against unprotected targets.