Schedule the time.

Schedule the time.Developmental Counseling and Professional Development

You may or may not intend to make the Army a career, but it is important to the future of the Army that you develop and prepare to assume positions of greater responsibility. The demands of combat may put even junior enlisted soldiers into leadership positions in stressful situations. This is why the Army puts so much effort into developing soldiers and training them to lead. This chapter will provide you with a basic understanding of the importance of developmental counseling and its relation to professional development. The Army has well-developed professional development and education systems that will help you learn–but you will have to do the work and provide the motivation.

Section I - Developmental Counseling

The Developmental Counseling Process

Types of Developmental Counseling

Section II - Professional Development

Section III - Retention And Reenlistment

For more information on developmental counseling see FM 6-22 (22-100), Army Leadership, Appendix B and C and the Army counseling website at www.counseling.army.mil.

For more information on professional development see AR 350-17, Noncommissioned Officer Development Program, DA PAM 350-58, Leader Development for America’s Army, and DA PAM 600-3, Commissioned Officer Development and Career Management, DA PAM 600-11, Warrant Officer Professional Development or DA PAM 600-25, US Army Noncommissioned Officer Professional Development Guide.

For more information on retention and reenlistment see AR 140-111, US Army Reserve Reenlistment Program, and AR 601-280, Army Retention Program.

SECTION I - DEVELOPMENTAL COUNSELING

6-1. Development counseling is a type of communication that leaders use to empower and enable soldiers. It is much more than providing feedback or direction. It is communication to help develop a soldier’s ability to achieve individual and unit goals. Leaders counsel soldiers to help them be successful. Effective developmental counseling is one of the ways you will learn and grow. Leaders owe their soldiers the best possible road map to success. Leaders help their soldiers solve complex problems by guiding them to workable solutions through effective counseling.

6-2. Developmental counseling is subordinate-centered communication that outlines actions necessary for soldiers to achieve individual and organizational goals and objectives. It is vital to the Army’s future that all leaders conduct professional growth counseling with their soldiers to develop the leaders of tomorrow.

6-3. Subordinate-centered, two way communication is simply a style of communication where you as a subordinate are not a passive listener, but a vital contributor in the communication process. The purpose of subordinate-centered communication is to allow the subordinate to maintain control and responsibility for the issue. This type of communication where you as a subordinate take an active role takes longer. Subordinate participation is absolutely necessary when leaders are attempting to develop and not simply impart direction or advice.

COUNSELING IS AN OBLIGATION

6-4. NCOs counsel their subordinate NCOs and junior enlisted soldiers, and officers will counsel subordinate leaders. For example, the company commander counsels the first sergeant. There may be situations where officers counsel junior enlisted soldiers. The point is this: every leader has an obligation to develop their subordinates through developmental counseling. The Army values play a very important role. Simply put the values of loyalty, duty and selfless service require leaders to counsel their soldiers. The values of honor, integrity and personal courage require both leaders and soldiers to give straightforward feedback and, if possible, goal-oriented tasks or solutions. The Army value of respect requires us all to find the best way to communicate that feedback and goals.

6-5. Some skills leaders use in effective counseling are the following:

• Active listening: Giving full attention to subordinates; listening to their words and the way they are spoken. Transmit and understanding of message through responding.

• Responding: Use appropriate eye contact and gestures. Check understandings, summarize, interpret and question.

• Questioning: Serves as a way to obtain valuable information and get subordinates to think. Most questions should be open-ended.

6-6. Some soldiers may perceive counseling as an adverse action, perhaps because that is their experience. Developmental counseling most definitely is not supposed to be an adverse action. Regular developmental counseling is the Army’s most important tool for developing future leaders at every level. Regular effective developmental counseling helps all soldiers become better members of the team, maintain or improve performance, and prepare them for the future. Regular counseling helps leaders and soldiers communicate more clearly and efficiently. Therefore soldiers should want to be counseled. Effective counseling must include some of the following elements:

• Purpose: Clearly define the purpose of the counseling.

• Flexibility: Fit the counseling style to the character of each soldier and to the relationship desired.

• Respect: View soldiers as unique, complex individuals, each with their own sets of values, beliefs, and attitudes.

• Communication: Establish open, two-way communication with the soldier using spoken language, non-verbal actions, and gestures and body language. Effective counselors listen more than they speak.

• Support: Encourage soldiers through actions while guiding them through their problems.

6-7. Leaders conduct counseling to assist soldiers in achieving and developing personal, professional development and organizational goals, and to prepare them for increased responsibility. Leaders are responsible for developing soldiers through teaching, coaching, and counseling. This is done effectively by identifying weaknesses, setting goals, developing and implementing a plan of action, and providing oversight and motivation throughout the process. Leaders are responsible for everything their units do or fail to do; your leader is responsible for all your military actions. Inherent in that responsibility is the duty to help you develop, and, one day, make you ready to lead.

EFFECTIVE COUNSELING PROGRAM

6-8. It is in the unit’s best interest to establish an effective counseling program. Four essential elements of an effective counseling program are education and training; experience; continued support; and enforcement.

6-9. Education and training occurs in the institution (for example, Primary Leadership Development Course or Captain’s Career Course) and unit (NCO Development Program and correspondence courses), and through mentorship and self-development. The Army provides a base line of education to its soldiers in order to “show what right looks like.” The Noncommissioned Officer Education System (NCOES) is an example and educates the NCO Corps on counseling. However, NCOES cannot accomplish this alone. Unit NCO development programs conduct training to provide that base of education of what right looks like to all leaders.

6-10. Soldiers learn by doing and receive guidance from more senior leaders. After initial education and training, all leaders must put their skills to use. NCOs must practice counseling while at the same time receiving guidance and mentoring on how to improve counseling techniques.

6-11. Continued support from both the Army and leaders is available from the Army’s counseling website (www.counseling.army.mil), FM 6-22 (22- 100), Appendix B and C, and unit leaders (through spot checks and random monitoring of counseling sessions). These provide necessary support and critiques that will improve a young leader’s counseling skills.

6-12. Enforcement is a key component of an effective developmental counseling program. Once leaders have the tools (both education and support) necessary for quality counseling, senior leaders must hold them accountable to ensure acceptable counseling standards for both frequency and content. This is often accomplished through some type of compliance inspections.

THE DEVELOPMENTAL COUNSELING PROCESS

6-13. The Developmental Counseling process consists of four stages:

• Identify the need for counseling

• Prepare for counseling

Schedule the time.

Schedule the time.

Notify the counselee well in advance.

Notify the counselee well in advance.

Organize information.

Organize information.

Outline the components of the counseling session.

Outline the components of the counseling session.

Plan counseling strategy.

Plan counseling strategy.

Establish the right atmosphere.

Establish the right atmosphere.

• Conduct the counseling session:

Open the session.

Open the session.

Discuss the issue.

Discuss the issue.

Develop a plan of action (to include the leader’s responsibilities).

Develop a plan of action (to include the leader’s responsibilities).

Record and Close the Session.

Record and Close the Session.

• Follow-up.

Support Plan of Action Implementation.

Support Plan of Action Implementation.

Assess Plan of Action.

Assess Plan of Action.

TYPES OF DEVELOPMENTAL COUNSELING

6-14. Counseling serves many purposes. Each type of counseling has a unique goal or desired outcome and sometimes uses a different method. In some cases a specific event may trigger a need for developmental counseling. In all cases, the goal is to improve the team’s performance by helping the counseled soldier become a more effective member of the team. As a counselee you should expect to be actively involved in the developmental counseling process. The leader is assisting you in identifying your strengths and weaknesses.

EVENT-ORIENTED COUNSELING

6-15. Event-oriented counseling involves a specific event or situation. It may precede events, such as going to a promotion board or attending a school, or it may follow events, such as a noteworthy duty performance, a problem with performance of mission accomplishment, or a personal problem.

Counseling for Specific Instances

6-16. Sometimes counseling is tied to specific instances of superior or substandard duty performance. For example, if you performed exceptionally well during an inspection, your squad leader might review your preparation for and conduct during the inspection. The key to successful counseling for specific performance is to conduct the counseling session as close to the time of the event as possible. It doesn’t necessarily occur next to a desk with a counseling form in hand. It can occur in an informal setting. But it is important to have a record of some kind for reference later in a regular performance counseling.

Informal “Footlocker” Counseling

Bravo Company had gotten back from the field on Wednesday, and by Thursday PFC Newman already had his HMMWV standing tall. SSG Ulbrich, his squad leader, was impressed that he had squared his vehicle away so quickly. She called him over to his vehicle and in a few minutes they reviewed together the work he had accomplished to conduct PMCS and get it ready to go again.

While she knew PFC Newman had worked through lunch, she also learned he had helped another soldier clean his personal gear in the barracks after duty hours.

“Keep this up, Newman,” she said, “You are a great example to the other soldiers and are developing into a fine leader, too.”

At the end of the day, the platoon leader called PFC Newman out in front of the formation and gave him a “pat on the back” in front of his fellow soldiers.

Reception and Integration Counseling

6-17. Leaders must counsel new team members when they report in. Reception and integration counseling serves two purposes: first, it identifies and helps fix any problems or concerns that new members have, especially any issues resulting from the new duty assignment; second, it lets you know the unit standards and how you fit into the team. Reception and integration counseling starts the team building process. It clarifies your responsibilities and sends the message that the chain of command cares. Reception and integration counseling should begin immediately upon arrival so you can quickly become integrated into the organization.

Promotion Counseling

6-18. Commanders or their designated representatives must conduct promotion counseling for all specialists, corporals, and sergeants who are eligible for advancement without waiver, but are not recommended for promotion to the next higher grade. Army Regulation 600-8-19, Enlisted Promotions and Reductions, requires that AC soldiers within this category receive initial (event-oriented) counseling when they attain full eligibility and then periodic (performance and personal growth) counseling at least quarterly.

Promotion Counseling

SSG Dills counseled SPC Snyder on his eligibility for promotion and sadi he would recommend him for the next promotion board. After completion of the promotion point worksheet (DA Form 3355), SPC Snyder found out that he had only 200 points—just enough to appear before the board. The minimum requirement to be placed on the SGT promotion list is 350 points. SPC Snyder would need to get a maximum score on the board to obtain the additional 150 points required for promotion to SGT. SPC Snyder was confident that he would pass the board and assured SSG Dills, “This will be easy, I won’t have a problem, Sergeant.”

SPC Snyder got his chance and appeared before the sergeant promotion board. He received 149 points from the board members. Although SSG Dills recommended SPC Snyder for promotion he would have to counsel him again because he did not have enough points to be added to the list.

During the next promotion counseling session, SSG Dills had appropriate tools and paperwork available (AR 600-8-19, DA Form 3355-Promotion Point Worksheet, and DA Form 4856-E--Counseling Form) and a proposed plan of action that they talked over. SPC Snyder helped develop the plan of action for ensuring he had enough points for promotion next time.

Crisis Counseling

6-19. You may receive counseling to help you get through the initial shock after receiving negative news, such as notification of the death of a loved one. Your leader will help you by listening and providing assistance as appropriate. That assistance may include help from a support activity or coordinating external agency support. Crisis counseling focuses on your immediate, short-term needs.

Referral Counseling

6-20. Referral counseling helps soldiers work through a personal situation and may follow crisis counseling. Referral counseling also acts as preventative counseling before a situation becomes a problem. Usually, the leader assists the soldier in identifying the problem.

6-21. Outside agencies can help your leaders help you resolve problems. Although it is generally in your best interest to seek help first from your immediate supervisor, leaders will always respect your right to contact these agencies on your own. But leaders, through experience, have developed a feel for what agency can help in a given situation and can refer you to the appropriate resource, such as Army community services, a chaplain, or a substance abuse counselor. You can find more information on support activities in Appendix B, Army Programs or in FM 6-22 (22-100), Appendix C.

Adverse Separation Counseling

6-22. Adverse separation counseling may involve informing a soldier of the administrative actions available to the commander in the event substandard performance continues and of the consequences associated with those administrative actions. Developmental counseling may not apply when a soldier has engaged in more serious acts of misconduct. In those situations, the leader should refer the matter to the commander or the servicing staff judge advocate’s office.

PERFORMANCE AND PROFESSIONAL GROWTH COUNSELING

Performance Counseling

6-23. During performance counseling, you review your duty performance with your supervisor. You and your leader jointly establish performance objectives and standards for the next period. Rather than dwelling on the past, you both should focus the session on the strengths, areas needing improvement, and potential. Performance counseling communicates standards and is an opportunity for leaders to establish and clarify the expected values, attributes, skills, and actions. Performance counseling is required for noncommissioned officers; mandatory, face-to-face performance counseling between the rater and the rated NCO is required under the NCOER system. It is a generally accepted standard that all soldiers receive performance counseling at least monthly.

Professional Growth Counseling

6-24. Professional growth counseling includes planning for the accomplishment of the individual and professional goals. You conduct this counseling to assist subordinates in achieving organizational and individual goals. Professional growth counseling begins with an initial counseling within the first 30 days of arrival. Additional counseling occurs quarterly thereafter with a periodic assessment (perhaps at a minimum of once a month). Counseling then is a continuous process.

6-25. During the counseling you and your leader will identify and discuss together your strengths/weaknesses and then create a plan of action to build upon your strengths and overcome weaknesses. The leader will help you help yourself and focus more towards the future. This future-oriented approach establishes short and long-term goals and objectives. FM 6-22 (22- 100), Appendix B, provides the necessary tools to do a self-assessment to help you identify your weaknesses and strengths and provide a means of improving your abilities and skills.

SECTION II – PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT

6-26. Leader development in the Army occurs in three pillars: institutional training, operational assignments, and self development. The Army’s education systems—institutional development—are key to leader development. These systems provides leader and skill training in an integrated system of resident training at multiple levels. In both the officer and NCO systems, this is a continuous cycle of education, training, experience, assessment, feedback, and reinforcement.

Everybody’s got to know how to be a leader.

GEN Peter J. Schoomaker

6-27. The needs of the unit and the demonstrated potential of the leader are always kept in focus and balance at all times. The emphasis is on developing competent and confident leaders who understand and are able to exploit the full potential of current and future Army doctrine. Self-development ties together a soldiers’ experience and training to make them better leaders, which ultimately benefit their units’ combat readiness.

INSTITUTIONAL TRAINING

6-28. Institutional training includes all the formal training you receive in the “schoolhouse.” Institutional training provides the basic knowledge, technical, tactical, and leadership skills needed at appropriate levels in a soldier’s career. Institutional training is primarily composed of the Officer, Warrant Officer, Noncommissioned Officer Education Systems.

THE OFFICER EDUCATION SYSTEM (OES)

6-29. The OES prepares officers for increased responsibilities and successful performance at the next higher level. It provides precommissioning, branch, and leader development training to develop officers to lead platoon, company, battalion, and higher level organizations. The Officer Education System is a combination of branch-immaterial and branch-specific courses providing progressive and sequential training throughout an officer’s career.

Precommission Training

6-30. The United States Military Academy, ROTC, and Federal/State OCS educate and train cadets/officer candidates and assess their readiness and potential for commissioning as second lieutenants. Precommission sources share a common goal that each graduate possesses the character, leadership, and other attributes essential to progressive and continuing development throughout a career of exemplary service to the Nation.

Officer Basic Course (OBC)

6-31. The OBC is a branch-specific qualification course that provides new second lieutenants an opportunity to acquire the basic leader, tactical, and technical skills needed to succeed at their first duty assignment. Some branch OBC graduates (military intelligence or chemical for example) are trained for success as a battalion staff officer.

Captains Career Course (CCC)

6-32. The CCC is a multiple-phased course providing captains an opportunity to acquire the advanced leader, tactical, and technical skills needed to lead company-size units and serve at battalion and/or brigade staff levels. The first phase is branch-specific training. The second phase is branch-immaterial staff process training to provide skills necessary for success in single service, joint, and combined environments. Captains learn to function as staff officers by improving their abilities to analyze and solve military problems, communicate, and interact as members of a staff.

Command and General Staff Officer Course (CGSOC)

6-33. The CGSOC educates promotable captains and majors in the values and practice of the profession of arms. It emphasizes tactical and operational skills required for warfighting at the corps and division levels. Graduates of CGSOC receive credit for Joint Professional Military Education Phase I. Alternate attendance may be at the Air Command and Staff College, the Naval War College, the U.S. Marine Corps Command and Staff College, the Western Hemisphere Institute for Security Cooperation Command and Staff College, and foreign military colleges approved/validated by CGSOC.

Army War College (AWC)

6-34. Various senior service colleges (SSC) offer capstone professional military education. The Army SSC is AWC at Carlisle Barracks, PA. The AWC prepares selected military, civilian, and international leaders to assume strategic leadership responsibilities in military or national security organizations. It educates leaders and the Nation on the employment of land power as part of a unified, joint, or multinational force in support of the national military strategy; researches operational and strategic issues; and conducts outreach programs that benefit the AWC, the Army, and the Nation.

WARRANT OFFICER EDUCATION SYSTEM (WOES)

6-35. The WOES prepares warrant officers to successfully perform in increasing levels of responsibility throughout an entire career. The WOES provides the preappointment, branch MOS-specific, and leader development training needed to produce technically and tactically competent warrant officer leaders for assignment to platoon, detachment, company, battalion, and higher level organizations. The WOES is a combination of branch-immaterial and branch-specific courses providing progressive and sequential training throughout a warrant officer’s career.

Warrant Officer Candidate Course (WOCC)

6-36. The WOCC is a MOS/branch immaterial course that assesses the potential of candidates to become successful Army warrant officers, and to provide training in basic officer and leader competencies. Evaluation and training occur in a mentally and physically demanding environment. Contingent upon certification by a branch proponent that they are technically and tactically qualified for award of an authorized warrant officer MOS, WOCC graduates are appointed to warrant officer, grade WO1.

Warrant Officer Basic Course (WOBC)

6-37. The WOBC (including the Initial Entry Rotary Wing Qualification Course) is the MOS-specific training and technical certification process conducted by branch proponents to ensure all warrant officers have attained the degree of leadership, technical and tactical competence needed to perform in their MOS at the platoon through battalion levels. Training is performance-oriented and focuses on technical skills, leadership, effective communication, unit training, maintenance operations, security, property accountability, tactics, ethics, and development of and caring for subordinates and their families.

Warrant Officer Advanced Course (WOAC)

6-38. The WOAC is MOS-specific designed to build on the tasks and VASA developed through previous training and experience. The course provides Chief Warrant Officers in grade CW3 the leader, tactical, and technical training to serve in company and higher-level positions. Primary focus is directed toward leadership skill reinforcement, staff skills, and advanced MOS-specific training. Warrant Officer Advanced Course training consists of a nonresident phase and a resident course.

Warrant Officer Staff Course (WOSC)

6-39. The WOSC is a branch-immaterial resident course. The course focuses on the staff officer tasks, leadership skills, and knowledge needed to serve in grade CW4 positions at battalion and higher levels. Instruction includes decisionmaking, staff roles and functions, organizational theory, structure of the Army, budget formation and execution, communication, training management, personnel management, and special leadership issues.

Warrant Officer Senior Staff Course (WOSSC)

6-40. The WOSSC is the capstone for warrant officer professional military education. This branch-immaterial resident course provides warrant officers with a broader Army perspective required for assignment to grade CW5-level positions as technical, functional, and branch systems integrators and trainers at the highest organizational levels. Instruction focuses on "how the Army runs" (force integration) and provides up-to-date information on Army-level policy, programs, and special items of interest.

THE NCO EDUCATION SYSTEM (NCOES)

6-41. Institutional training for enlisted soldiers probably began in Initial Entry Training (IET). But the continuing education of junior enlisted soldiers is why our Army’s NCO corps is the best in the world. Soldiers who have the potential for greater responsibility and the willingness to accept it will receive training to prepare them for that responsibility.

Primary Leadership Development Course (PLDC)

6-42. The first leadership course a promotable specialist or NCO will attend is the non-MOS specific Primary Leadership Development Course (PLDC) conducted at NCO Academies (NCOA) worldwide. Soldiers on a promotion list who have met a cutoff score and are otherwise qualified may receive conditional promotion to Sergeant before completion of PLDC.

Basic Noncommissioned Officer Course (BNCOC)

6-43. Combat arms (CA), combat support (CS), and combat service support (CSS) basic course occurs at proponent service schools. Successful completion of BNCOC is a prerequisite for consideration for promotion to sergeant first class. Active component sergeants promotable to staff sergeant who have met an announced cutoff score can attend BNCOC but must complete the course within one year. Reserve component sergeants must first complete Phase I. Training varies in length from two to nineteen weeks with an average of nine weeks. A 12-day common core designed by the US Army Sergeants Major Academy supplements leadership training received at PLDC. The Department of the Army funds all BNCOC courses. Priority for attendance is SSGs and SGTs (P).

Advanced Noncommissioned Officer Course (ANCOC)

6-44. Department of the Army selects ANCOC attendees by a centralized SFC/ANCOC selection board. The zone of consideration is announced by personnel services command (PERSCOM) before each board convenes. Promotable SSGs can be conditionally promoted prior to attending ANCOC but must complete the course within a year. Promotable SSGs who meet the announced promotion sequence number can be conditionally promoted prior to and during the course. All soldiers selected for promotion to SFC who have not previously attended ANCOC are automatic selectees. Priority of ANCOC attendance is for SFC and SSG (P).

Sergeants Major Course (SMC)

6-45. The Sergeants Major Course is the senior level NCOES course and the capstone of NCO education. Soldiers selected for SMC attend a resident course or a non-resident course. A Department of the Army centralized selection board determines who attends resident or non-resident training. The nine month resident course is conducted at the US Army Sergeants Major Academy (USASMA) in Fort Bliss, Texas. Selected individuals may complete SMC through non-resident training, which includes a two week resident phase at USASMA. Soldiers selected for promotion to SGM who are not graduates will attend the next resident SMC. Soldiers may not decline once selected. Successful completion of SMC is a requirement for promotion to SGM. MSGs (P) can be conditionally promoted to SGM prior to and during the course. NCOs who complete SMC incur a two-year service obligation upon graduation.

OPERATIONAL ASSIGNMENTS

6-46. Operational experience provides soldiers the opportunity to use and build upon what was learned through the process of formal education. Experience gained through a variety of challenging duty assignments prepares soldiers for combat or other operations. A soldier’s MOS is usually the basis for operational assignment.

The successful leader knows that for him to excel, his soldiers must excel.

MAJ Don T. Riley

6-47. Developing leaders is a priority mission in command and organizations. Commanders, leaders and supervisors develop soldiers and ensure necessary educational requirements are met. Commanders establish formal unit LDPs that focus on developing individual leaders. These programs normally consist of three phases: reception and integration, basic skill development, and advanced development and sustainment.

• Reception and Integration. The squad leader and platoon sergeant interview new soldiers and discuss his duty position, previous experience and training, personal goals, and possible future assignments. Some units may administer a diagnostic test to identify strengths and weaknesses.

• Basic Skill Development. The new soldier attains a minimum acceptable level of proficiency in critical tasks necessary to perform his mission. The responsibility for this phase lies with the new soldier’s immediate supervisor, assisted by other key NCOs and officers.

• Advanced Development and Sustainment. This phase sustains proficiency in tasks already mastered and develops new skills. This is often done through additional duty assignments, technical or developmental courses, and self-development.

6-48. Commanders and leaders use the unit Leader Development Program (LDP) and NCO Development Program (NCODP) to enhance NCO development during operational assignments. The unit NCODP is the CSM’s leader development program for NCOs (CPL through CSM). The unit NCODP encompasses most training at the unit level and is tailored to the unique requirements of the unit and its NCOs. The unit NCODP should include primarily METL-driven tasks but may also include general military subjects such as customs, courtesies and traditions of the US Army.

SELF-DEVELOPMENT

6-49. Self-development is a life-long, standards-based, and competency driven process that is progressive and sequential and complements institutional and operational experiences to provide personal and professional development. It is accomplished through structured and non-structured, technical and academic learning experiences conducted in multiple environments using traditional, technology-enhanced and self-directed methods. Self-development consists of individual study, education, research, professional reading, practice, and self-assessment. You can find a a list of Internet resources in Appendix D and a professional reading list in Appendix E.

A [soldier] cannot lead without… studying, reading, observing, learning. He must apply himself to gain the goal—to develop the talent for military leadership.

MSG Frank K. Nicolas

6-50. Self-development includes both structured and self-motivated development tasks. At junior levels, self-development is very structured and narrowly focused. It is tailored towards building the basic leader skills and closely tied with unit NCO development programs. The components may be distance learning, directed reading programs, or other activities that directly relate to building direct leader skills. As NCOs become more senior in rank, self-motivated development becomes more important–activities like professional reading or college courses that help the senior NCO develop organizational leadership skills.

6-51. Professional development models (PDM) are available for each career management field. You can find these at each career branch website and in DA PAM 600-25, “The US Army Noncommissioned Officer Professional Development Guide.” PDMs provide both career and educational road maps for NCOs to assist in self-development.

EDUCATIONAL ACTIVITIES IN SUPPORT OF SELF-DEVELOPMENT

6-52. Self-development activities recommended in PDMs draw on the programs and services offered through the Army Continuing Education System (ACES) which operate education centers throughout the Army. In addition, Army Knowledge Online (AKO) has links to computer-based training courses (e-learning) available to all soldiers and DA civilians. Some other educational services that may assist in self-development are the following:

• Education Center Counseling Service.

• Functional Academic Skills Training.

• Testing.

• Language Training.

• Correspondence Courses.

• Army Learning Centers.

PROMOTIONS

6-53. Promotions are one of the most visible means of recognizing the performance and potential of soldiers. With promotion to higher rank usually comes greater responsibility and more complex duties. In the next few pages are brief descriptions of the promotion systems of the active component, Army National Guard and US Army Reserve. Since promotion eligibility periodically changes, you should refer to the governing regulation to find out the most current criteria.

6-54. In general terms, promotions are accomplished in a decentralized, semi-centralized or centralized manner. Decentralized promotions are controlled and executed at the unit level. For example, active component commanders may promote an eligible PV2 to PFC in a decentralized system. In semi-centralized promotions, part of the process is at unit level (boards). For promotions to SSG, for example, units convene boards to recommend SGTs for promotion to SSG. Those SGTs the board recommends then receive promotion when they attain the number of promotion points required by centralized cut-off score lists. The Army convenes centralized promotion boards to consider soldiers for promotion to LTC, for example.

ENLISTED PROMOTION OVERVIEW (ACTIVE COMPONENT)

6-55. The regulation that governs active component enlisted promotions and reductions is Army Regulation 600-8-19, Enlisted Promotions and Reductions. It provides the objectives of the Army’s enlisted promotion system, which include filling authorized enlisted spaces with the best-qualified soldiers. The promotion system provides for career progression and rank that is in line with potential, recognizing the best qualified soldier to attract and retain the highest caliber soldier for a career in the Army. Additionally, it precludes promoting the soldier who is not productive or not best qualified, providing an equitable system for all soldiers.

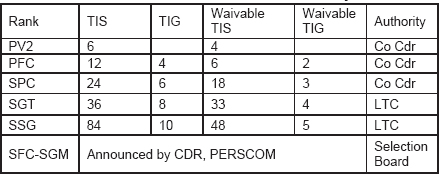

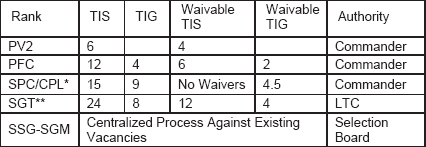

6-56. Promotions for enlisted soldiers to PV2, PFC and SPC are decentralized. Soldiers receive automatic promotion to PV2 after 6 months time in service (TIS). Soldiers are automatically promoted to PFC after 12 months TIS and 4 months time in grade (TIG). Soldiers are automatically promoted to SPC after 26 months TIS and 6 months TIG. In all cases, promotions occur unless the commander takes action to prevent the promotion. Based on strength computations at the battalion level, there may be allocations available to promote soldiers earlier than the automatic TIG/TIS requirements. Table 6-1 shows TIG/TIS requirements for promotions PV2-SSG.

Table 6-1. Promotion Criteria-Active Duty

Note: TIS/TIG in months

6-57. Precedence of relative rank. Among enlisted soldiers of the same grade or rank in active military service (to include retired enlisted soldiers on active duty) precedence of relative rank is determined as follows:

• Date of rank (DOR).

• Length of active Federal service in the Army when DORs are the same.

• By length of total active federal service when a and b above are the same.

• Date of birth when a, b, and c are the same. Older is more senior.

6-58. Date of rank and effective date:

• The DOR for promotion to a higher grade is the date specified in the promotion instrument or when no date is specified is the date of the instrument of promotion.

• The DOR in all other cases will be established as governed by appropriate regulation.

• The DOR in a grade to which reduced for inefficiency or failure to complete a school course is the same as that previously held in that grade. If reduction is a grade higher than that previously held, it is the date the soldier was eligible for promotion under the promotion criteria set forth for that grade under this regulation.

• The DOR on reduction for all other reasons is the effective date of reduction.

• The DOR and the effective date will be the same unless otherwise directed by the regulation.

6-59. Soldiers receive conditional promotion to SSG, SFC, and SGM. The Army is reemphasizing the requirement for soldiers to attend and graduate scheduled NCOES courses to retain conditional promotions. For SSGs, SFCs or SGMs to retain conditional promotions, they must complete BNCOC, ANCOC or the US Army Sergeants Major Course (respectively).

6-60. The conditional promotion is for a 12 month period. If conditionally promoted soldiers are enrolled in the appropriate NCOES course at the end of the 12 month period, they may complete the training and retain their promoted rank upon graduation. Soldiers who do not complete the training for justifiable reasons (as described in AR 600-8-19) will lose their conditional promotion and be reduced to the previous rank. Conditionally promoted soldiers who fail to complete the course for any of the following reasons will be reduced to the previous rank and removed from the promotion selection list:

• Soldiers who fail to attend their scheduled class (unjustified reason).

• Soldiers who are denied enrollment for failure to meet weight standard in AR 600-9, The Army Weight Control Program.

• Soldiers released from the course for failure to meet course standards.

6-61. Soldiers may receive conditional promotion to SGT. If a soldier meets the appropriate cutoff score and is otherwise qualified, but has not yet completed PLDC, the soldier receives conditional promotion under the following conditions:

• Soldier is on the unit order of merit list (OML) for attendance to PLDC.

• Soldier is operationally deployed (not including National Training Center or Joint Readiness Training Center).

• Soldier is on temproary profile that prohibits attendance at PLDC.

ENLISTED PROMOTIONS OVERVIEW (ARMY NATIONAL GUARD)

6-62. Like its active counterpart the Army National Guard promotion system is designed to help fill authorized enlisted vacancies with the best qualified enlisted soldiers who have demonstrated the potential to serve at the next higher grade in line with each soldier’s potential. For the NCO grades, it prescribes the NCOES requirement for promotion: the soldier on the list will attend the course required for promotion to that grade.

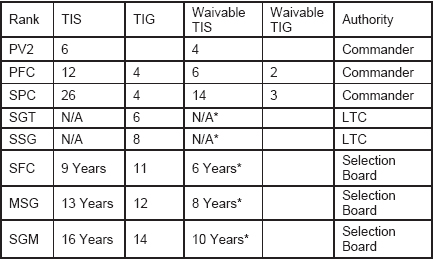

6-63. Table 6-2 shows the TIS/TIG requirements for enlisted promotions in the Army National Guard.

Table 6-2. Promotion Criteria-Army National Guard

Note: TIS/TIG in months unless otherwise noted. * Cumulative Enlisted Service

6-64. The Chief, National Guard Bureau, is the convening and promotion authority for active guard and reserve (AGR) Title 10 enlisted soldier attached to NGB and active duty installations. State Adjutants General (AG) are convening and promotion authority for all promotion boards to SGT through and SGM. They may delegate their authority to their Assistant AG (Army) or Deputy State Area Reserve Command (STARC) commander. They also may delegate promotion authority to subordinate commanders as follows:

• Commanders in MG positions may promote soldiers to SGM.

• Commanders in COL or higher positions may promote soldiers to SFC and MSG.

• Commanders in LTC or higher positions may promote soldiers to SGT and SSG.

• All other commanders may promote soldiers to PV2 and SPC.

ENLISTED PROMOTIONS OVERVIEW RESERVE (TROOP PROGRAM UNITS)

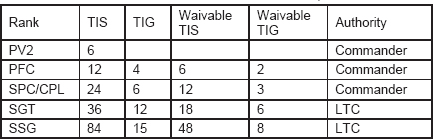

6-65. The promotion criteria for soldiers (PV2-SSG) in reserve troop program units (TPU) are shown in Table 6-3.

Table 6-3. Promotion Criteria-Reserve TPU, PV2-SSG

Note: TIS/TIG in months.

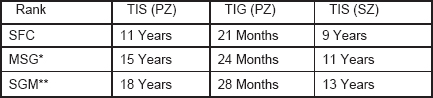

6-66. For promotion to SFC and higher rank, soldiers in reserve TPU undergo a centralized selection process. The promotion criteria for these soldiers are shown in Table 6-4.

Table 6-4. Promotion Criteria-Reserve TPU, SFC-SGM

Note: Promotion selection centralized at ARCOM/GOCOM/RSC headquarters and general officer commands OCONUS. * Must have 8 years CES. ** Must have 10 years CES

6-67. Active Guard and Reserve (AGR) soldiers promotion criteria are shown in Table 6-5.

Table 6-5. Promotion Criteria-Active Guard and Reserve

Note: TIS/TIG in months. * Must have completed a minimum of three continuous months on AGR status. ** Must have completed a minimum of 6 months on AGR status.

6-68. The promotion criteria for individual ready reserve (IRR), individual mobilization augmentee (IMA), and standby reserve (active list) soldiers are shown in table 6-6.

Table 6-6. Promotion Criteria-IRR, IMA, and Standby Reserve (Active List)

| Rank | TIG (in months) |

| PFC | 12 |

| CPL/SPC | 12 |

| SGT | 24 |

| SSG | 36 |

| SFC | 36 |

| MSG | 24 |

| SGM | 28 |

Commander, PERSCOM is the promotion authority for all IRR, IMA and Standby Reserve (Active List) soldiers.

All soldiers must be in the IRR or Standby Reserve (Active List) for a 1-year period to be considered for promotion.

The advancement and promotion of soldiers assigned to the IRR are limited to PV2 through SFC.

The advancement and promotion of soldiers assigned to IMA positions or Standby Reserve (Active List) are limited to PFC through SGM.

Soldier must have earned 27 retirement points in either of the two years preceding selection for promotion.

OFFICERS PROMOTION OVERVIEW

6-69. All AC officer promotions are done through the centralized promotion system and are governed by procedures based on Title 10, United States code, Army Regulation (AR 600-8-29, Officer Promotions), and policy established by the Secretary of the Army and the Deputy Chief of Staff for personnel.

6-70. The basic concept of the promotion selection system is to select for promotion those officers who have demonstrated that they possess the professional and moral qualifications, integrity, physical fitness, and ability required to successfully perform the duties expected of an officer at the next higher grade. Promotion is not intended to be a reward for long and honorable service in the present grade but is based on overall demonstrated performance and potential abilities.

6-71. Promotion selection is conducted fairly and equitably by boards composed of mature, experienced senior officers. Each board consists of different members, and women and minority members are routinely appointed. Selection boards recommend those officers who, in the collective judgment of the board, are the best qualified for promotion.

6-72. The Army has established procedures to counsel, upon request, officers not selected for promotion. An officer may request reconsideration for promotion when an action, by a regularly scheduled selection board which considered him or her for promotion, was contrary to law or involved material error.

SECTION III – RETENTION AND REENLISTMENT

The Oath of Enlistment

I, (name of enlistee) do solemnly swear (or affirm) that I will support and defend the Constitution of the United States against all enemies, foreign and domestic; that I will bear true faith and allegiance to the same; that I will obey the orders of the President of the United States and the orders of the officers appointed over me, according to regulations and the Uniform code of Military Justice. So help me God!

6-73. All commanders are retention officers. Commanders and NCOs at all levels have the responsibilities to sustain Army personnel readiness by developing and implementing and maintaining aggressive local Army retention programs designed to accomplish specific goals and missions consistent with governing laws, policies, and directives.

This country has done a lot for my family. This is a way to give back.

SPC Luis Feliciano

6-74. The goals of the Army Retention Program are to—

• Reenlist on a long-term basis, sufficient numbers of highly qualified active Army soldiers.

• Enlist or transfer and assign sufficient numbers of highly qualified soldiers who are separating from the active Army into RC units, consistent with geographic constraints.

• Achieve and maintain Army force alignment through the retention, transfer, or enlistment of highly qualified soldiers in critical skills and locations.

• Adequately support special programs such as the US Military Academy Preparatory School (USMAPS) and ROTC “Green to Gold” programs.

6-75. Commanders are issued retention missions based upon their “fair share” ratio of enlistment eligible soldiers. Commanders receive missions in the following categories:

• Regular Army Initial Term mission.

• Regular Army Mid-Career mission. Soldiers serving on their second or subsequent term of service, having 10 or less years of Active Federal Service at ETS.

• RC enlistment/transfer mission. This mission is based upon the number of eligible in the ranks of CPL/SPC and SGT scheduled for ETS and may be assigned as required by HQDA.

• Missions as otherwise required by DA. Missions are to include the USMAPS and ROTC Green to Gold programs.

Reenlisting in Kandahar, Afghanistan.

6-76. DA policy states that only those soldiers who have maintained a record of acceptable performance will be offered the privilege of reenlisting within the active Army or transferring or enlisting into the RC. Other soldiers will be separated under appropriate administrative procedures or barred from reenlistment under Chapter 8, AR 635-200.

The end for which a soldier is recruited, clothed, armed, and trained, the whole object of his sleeping, eating, drinking, and marching is simply that he should fight at the right place and the right time.

Carl von Clausewitz

BONUS EXTENSION AND RETRAINING (BEAR) PROGRAM

6-77. BEAR is a program designed to assist in force alignment. It allows eligible soldiers an opportunity to extend their enlistment for formal retraining into a shortage MOS that is presently in the Selective Reenlistment Bonus (SRB) program. Upon completion of retraining, the soldier is awarded the new primary military occupational specialty (PMOS), reenlists, and receives an SRB in the newly awarded MOS.

6-78. The type of discharge that you will receive from the Army is based on your military record; for example, if you are separated for administrative reasons other than completion of term in service, you may receive the following types of discharge. For more information on the effects of discharges see Chapter 7.

• Honorable. This type of discharge depends on your behavior and performance of duty. Isolated incidents of minor misconduct may be disregarded if your overall record of service is good.

• General Discharge under Honorable Conditions. This discharge is appropriate for those whose military records are satisfactory but are not good enough to warrant an honorable discharge.

• Discharge under Other Than Honorable Conditions. This is the most severe of the administrative discharges. It may result in the loss of veteran’s benefits. Such a discharge usually is given to those who have shown one or more incidents of serious misconduct.

• Entry-Level Separation. This discharge applies if you are within 180 days of continuous active duty and your records do not warrant a discharge under other than honorable conditions.

BARS TO REENLISTMENT

6-79. The bar is a procedure to deny reenlistment to soldiers whose immediate separation under administrative procedures is not warranted, but whose reentry into or service beyond end of time in service (ETS) with the active Army is not in the best interest of the Army. Soldiers may not reenlist without the recommendation of the commander. However, if a commander wishes to disapprove a request for reenlistment of extension when submitted by a soldier who is fully qualified for reenlistment without waiver, he or she must concurrently submit a Bar to Reenlistment.

6-80. The Bar to reenlistment is not a punitive action but is designed for use as a rehabilitative tool. Imposition of a bar does not preclude administrative separation at a later date. The Bar to Reenlistment puts a soldier on notice that he is not a candidate for reenlistment. A soldier who is barred from reenlistment realizes he may be subject to separation if the circumstances that led to the Bar to Reenlistment are not overcome. The commander who imposes the bar will advise the soldier exactly what is expected in order to overcome the Bar to Reenlistment. Commanders must review the circumstances for imposing the bar every three months and either remove or continue the bar to reenlistment.

6-81. Commanders must initiate separation proceedings under AR 600-200 upon completion of the second 3-month review if the commander decides not to remove the bar. Initiation of separation action is not required for soldiers who, at the time of the second 3-month review, have more than 18 years of active federal service but less than 20 years. These soldiers will be required to retire on the last day of the month when eligibility is attained.