The Old Order

Between 1850 and 1950 British industry dominated the world. The factories that fed Britain’s success were for the most part worked by white men. Most of what was traded was made by white men. Between 1850 and 1880 11,000 miles of railway track were laid mostly by white men. In 1850 men smelted 2.25 million tons of pig iron, rising to 7.75 million tons by 1880. In 1850 men forged 49,000 tons of steel rising to 1.44 million tons in 1880. And men dug 49 million tons of coal in 1850, rising to 147 million in 1880. The number of engineers doubled between 1851 and 1881, and carried on growing so that there were 1.1 million engineers in 1935, almost all of them white men.1 Throughout that time Britain was making between 10% and 15% of all manufactured goods in the world, with greater output per worker than any country, bar the United States.

Britain’s take-off was based primarily on industrial labour in factories, and, through two key changes, that labour was overwhelmingly the work of men. The first change was the move from domestic production to factory production. Seventeenth-century spinning and weaving was done indoors, like furniture-making and most other handicrafts. The factory system separated domestic work from wage labour under a different roof. Many of these early factories, though, had women working alongside men, and children too. The second change, which was driven by a moral revulsion at the exploitation of women and children in dangerous work, was a series of laws, clauses in the Factory Acts that restricted women’s work (Mines and Collieries Act, 1842; Factory Acts of 1844, 1878, 1891, and 1895).

In the census of 1911 there were 13,662,200 men aged over ten years, and 14,857,113 women. Of those 84% of men and 32% of women were in work. More pointedly just 10% of married women (around half the total of all women) were in work.2

The men’s labour in British factories depended on other work done elsewhere. There was the work done by women, mostly in the home — cooking, washing, cleaning, caring for children — that all added up to the raising and sustenance of the working men. Also, industrialising Britain gobbled up raw materials that were grown and harvested and mined by black and Asian people. Sugar, rubber, tin, and oil from the colonies fed the industrial revolution, as the profits of the slave trade and empire yielded the seed money that grew it. But in the second half of the nineteenth century the factory system was the primary source of its profits (profits that averaged around 25%).3 The most important relationship, and the one that dominated social and political life in Britain, was that between the wage-earning class and the propertied classes. Those workers at that time were overwhelmingly male and white — factors that would influence the culture and organisation of the working classes that emerged between 1850 and 1950.

The growth of organised labour was bound up with a sharply gendered division of labour, first and foremost between paid factory work and unpaid domestic work; it was also based upon a demarcation of British industrial workers from toilers in the Empire, and from largely unorganised Irish labourers.

Today we might be tempted to call the centrality of white men to the factory system ‘privilege’ — though that is not really the word to use for the lives they led. Explaining that these industrial workers were the source of their employers’ profits, Karl Marx said that ‘to be a productive labourer is, therefore, not a piece of luck, but a misfortune’.4 The hours worked in those days were long, generally more than 50 a week. The primitive extent of mechanisation also made working life dangerous, arduous, and dirty. The status of the nineteenth-century factory hand was low, and he was often dominated by his master, under threat of instant dismissal, subject to fines for misdemeanours.

In the earlier nineteenth century skilled craftsmen tried to control the work process by limiting the number of people in the trade, limiting membership of their associations, and so bidding up their wages. Women were not the main target — all rivals in the labour market were — but the strategy did institutionalise discrimination in employment. In South East England at that time, as many as 34% of all apprentices were women. But in 1796 the Spitalfields silk weavers excluded women from skilled work; in 1779 the journeymen bookbinders excluded women from their guild; the Cotton Spinners Union excluded women in 1829; and in 1834 London tailors struck work to force women out of the trade.5 These defensive measures also sharply differentiated the skilled from the unskilled, the craftsmen from the labourers. It was a division that could take on a racial aspect: ‘Every industrial and commercial centre in England now possesses a working class divided into two hostile camps, English proletarians and Irish proletarians’, Marx wrote: ‘The ordinary English worker hates the Irish worker as a competitor who lowers his standard of life.’6

The radical United Kingdom Alliance of Organised Trades formed in Sheffield in 1866 and the more moderate Trades Union Congress held its conference in Manchester in 1868. The establishment vilified the radicals as dynamiters, and rewarded the respectable head of the working-class household — but not his wife — with the vote in 1867. That year Lord Derby set up a Royal Commission on Trade Unions, and in a law of 1871 stopped them being classed as a conspiracy, and lifted the unions’ liability for employers’ losses in a dispute. The measure was meant to encourage responsible trade unionism, and it did.

The end of the Combination Acts was a thing that pulled in one way and another. On the one hand it made it possible for many more people to join unions. On the other hand, legalisation bedded down the more conservative side of working-class identity. They had offices and officers, standing agreements with employers, legal status, and a hearing in Royal Commissions. All of these cemented the more conservative outlook of organised labour. They laid a basis for a patriotic love of England, its parliament, and even its monarchy. Karl Marx wrote in 1883 that the English workers were participating in the country’s success, and

are naturally the tail of the ‘great Liberal Party,’ which for its part pays them small attentions, recognises trade unions and strikes as legitimate factors, has relinquished the fight for an unlimited working day and has given the mass of better placed workers the vote.7

Labour Force Survey, ONS — the dip in the middle is due to the recession between the two world wars

Christopher Kyriakides and Rodolfo Torres make the point that the vote and the chance of reform ‘was the British state’s policy tool through which racial proximity and distance were institutionalised’.8The workers’ patriotic identification with England and its institutions left them open to chauvinistic divisions, in particular against the Irish. ‘He cherishes religious, social, and national prejudices against the Irish worker’, Marx wrote of the English worker:

In relation to the Irish worker he regards himself as a member of the ruling nation and consequently he becomes a tool of the English aristocrats and capitalists against Ireland, thus strengthening their domination over himself.9

Legitimacy did not only entrench conservative attitudes towards the Irish, it also kindled a more patrician idea of the family.

As we have seen, successive employment laws tended to differentiate men’s and women’s work, limiting the hours that women worked, and barring them from more dangerous trades. The debate over the regulation of factory life turned on gender. ‘The public debate about enacting protective labour legislation in England’, says researcher Carolyn Malone, was all about the ‘idea that women’s work outside the home was dangerous to society and required state intervention’. She cites Peter Gaskell’s book The Manufacturing Population of England (1833), where he warns that ‘crowding together of numbers of the young in both sexes in factories, is a prolific source of moral delinquency’. Gaskell lauded ‘the moral obligations of father and mother, brother and sister, son and daughter’ and warned against the breaking up of these family ties; the consequent abolition of the domestic circle, and the perversion of all the social obligations which should exist between parent and child under the factory system. These warnings against women’s work often turned on the harm to children — as they often do today. So Thomas Maudsley, of the nine-hour bill campaign, thought that ‘prolonged absence from home of the wife and mother caused an enormous amount of infant mortality and it must cause the elder children to be more or less neglected’. To him women’s work ‘deadened the sense of parental responsibility’.10 True as this was, women did not object to the protective laws, because the work conditions were exploitative and arduous. One factory inspector noted that ‘no instances have come to my knowledge of adult women having expressed any regret at their rights being interfered with’.11

A more profound influence of the division of labour between the sexes than the formal bars on women working in mines and other dangerous trades, or the limitation on women’s working hours, was the consequence of full-time, compulsory schooling for under-11s. Already in 1833 factories were forbidden from employing children under nine. The provision of free education under the Forster Act (1870) and the limit on children’s working hours were without doubt a great step forward.

As great an advance as it was for society and the law to enforce the protection of children, the impact upon women was that it greatly increased the need for childcare, as one of the main tasks of housework. MP Charles Buxton, supporting Forster’s education act, warned that ‘No feeling of tenderness for the parents would deter him for one minute from adopting compulsion’. He added that ‘Society was suffering grievously from their shameful apathy with regard to the education of their children’.12 A Board School in Upper Holloway minuted that ‘parents say they would be glad to send, but their girls’ services were needed at home’. Later, truant officers took older children who did much of the caring for their younger brothers and sisters away from their homes and back to school.13 There were campaigns, too, to police deviant sexual behaviour. The largely middle-class Social Purity Movement campaigned against prostitution and for ‘fallen women’. Henry Labouchère’s amendment to the 1885 Criminal Law Amendment Act outlawed ‘gross indecency’, and led to the imprisonment of thousands of homosexuals.

All of these interventions brought with them officials to police the newly created nuclear family — there were 250 NSPCC ‘cruelty men’, empowered under an act of 1889, truant officers, health visitors, and social workers, all making sure that an orderly home was being kept. This way women’s domestic role was vigorously enforced.

In 1877 the Secretary to the Parliamentary Committee of the Trades Union Congress, the same Henry Broadhurst we met earlier, told the Congress that it was the duty of male trade unionists ‘as men and husbands to use their utmost efforts to bring about a condition of things, where their wives should be in the proper sphere at home, instead of being dragged into competition for livelihood against the great and strong men of the world’. As a delegate of the Mason’s Union, Broadhurst perhaps had one foot in the old protectionism of the craft unions. But his views were echoed later by Tom Mann, the Dockers’ leader and champion of the ‘New Unionism’, who gave evidence to the Royal Commission of Labour in 1894 that he was ‘very loth to see mothers of families working in factories at all’, adding that he considered their employment to have ‘nearly always had a very prejudicial effect on the wages of the male worker’.14 Trade union leader and Liberal MP John Burns’ speech in the Dock Workers’ strike in 1889 was largely an appeal to the men to conduct themselves respectably, and not to beat their wives or drink.15

The ideal of the respectable male breadwinner had become established. Tory MP Charles Newdegate argued against votes for women, drawing on the case of those unions that had put in place rules against women. He told Parliament ‘the rightful head of the family claims for himself priority in labour as the chief breadwinner’, adding, ‘If that be selfishness, it is selfishness for the family’. Another MP, the rather radical Liberal Edward Pickersgill of Bethnal Green, appealed to the idea of the breadwinner to defend his constituents’ incomes, saying he ‘wanted to impress upon the conscience of the House that there were thousands of his constituents, bread-winners, earning wages in many cases not more than 20s. per week’. Arguing against the founding of a women’s college, the Liberal MP Stuart Rendel said that ‘after all, the men are the breadwinners, and must have the prior consideration’.16 In 1909 William Beveridge set out the meaning of the breadwinner role that had been set down in the later nineteenth century, saying that ‘society is built on labour’, and ‘its ideal unit is the household of man, wife and children maintained by the earnings of the first alone’. The liberal administrator added that ‘the wife, so long at least as she is bringing up children, should have no other task’.

In spite of these claims, it was not typical for any working-class family to survive on one wage alone. Sara Horrell and Jane Humphries estimated that male wage earnings as a share of all family income had risen from 55% in 1830 to 81% in 1865. Economist Arthur Bowley worked out that in 1911 — when the division of labour was most sharply based on gender — only 41% of working-class families were dependent on a man’s wage alone, and that on average the man’s wage made up just 70% of family income.17 What the family wage model did was not to exclude women entirely from paid work, but rather pushed them down the scale into less well-paid, less organised and less secure work. Substantially work inside the home had become women’s work; while outside the home paid work was segregated on gender lines, with women in the role of the ‘reserve army of labour’, that employers could draw upon more or less as the business cycle demanded. For those at the lower end of the income scale, the male breadwinner ideal fell apart, and poorer families took what work they could.

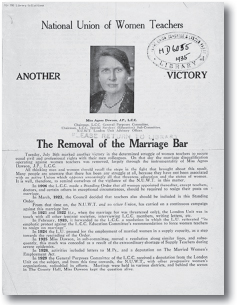

The idea of the family wage was in Edwardian England hardened up into a custom that was in effect a marriage bar — ‘the prohibition on married women’s employment which ensured that jobs, especially white-collar jobs, were reserved for men’. The Fabian Society’s Chiozza Money, in 1905, wrote that ‘the nation must set its face against the employment of married women, and gradually expand the period of legal prohibition’. To his mind ‘there is only one proper sphere of work for the married woman and that is her own home’. Catherine Hakim says that ‘strong social norms’ against women working were ‘sometimes institutionalised in company rules and policies’, as for example the BBC’s marriage bar, introduced in 1935. The marriage bar for teachers was not abandoned until 1945, and those in the civil service and the post office were not removed until 1954.18

TUC Library Collection

While men and women were divided into different roles, the true winners were the employers, who had the advantage of a male workforce that was committed whole-heartedly to the workshop, having been fed and kept by the unpaid work of women; and they had on top of that an additional reserve of labour that, being less organised and already dependent, was more malleable.

Between 1815 and 1914 Britain was at the centre of a transformation in the organisation of the global order. Ten million square miles of territory and 400 million people were colonised by Britain. The imperial economy secured raw materials for Britain’s industrial surge, and increasingly native labour was working to enrich Britain. Now it was Britain’s surplus capital that was overflowing, and rushing into the new territories.

At first it was the well-to-do who profited by the expansion, which the radical John Hobson called ‘a vast system of outdoor relief for the upper classes’. Britain’s imperial grandeur was also a powerful draw upon the imagination of working people. In the first half of the twentieth century, social reforms bound the British worker more closely to the Empire project, while at the same time raising up a great barrier between the British worker, who enjoyed greater rights, and colonial labourers who had very few. The ‘new Liberals’ of the turn of the century brought in a policy of social reform with investment in municipal and public utilities that was known as ‘Gas and Water Socialism’. Lloyd George overcame Tory opposition to a tax-raising budget that paid for pensions and primitive schemes of worker’s compensation and pensions. Trade union officers were drawn into the administration of social reforms through local boards, solidifying their identification with the state.

There had been a spate of conciliation boards — as on the railways and in the cotton industry — set up to moderate trade disputes in the 1860s. These were enshrined in law in the 1896 Conciliation Act and a special Labour Department in the Board of Trade set up in 1911 brought government directly into industrial relations. The conciliation boards gave union representatives recognised official status, and were conceded by employers as a part of the ‘routinisation of social conflict’.19

Herbert Asquith’s Liberal administration passed an act in 1909 that set up Labour Exchanges, and then in 1911 the National Insurance against unemployment and sickness. Unions were asked to help work the National Insurance fund, so that the militant labour activist Jack Murphy would write that ‘the unions were drawn closer to the state by the ingenious means of giving them a share in the administration of the state insurance funds’.20 Home Secretary Winston Churchill voiced the hope that reform would moderate labour: ‘With a “stake in the country” in the form of insurance against evil days these workers will pay no attention to the vague promises of revolutionary socialism.’21

The sociologist Robert Michels, looking at English and German labour organisation in 1915, said:

There already exists in the proletariat an extensive stratum consisting of the directors of co-operative societies, the secretaries of trade unions, the trusted leaders of various organisations, whose psychology is entirely modelled upon that of the bourgeois class with whom they associate.22

This new layer of labour bureaucracy became the foundation of the Labour Party, and an essential support to the corporate society that was built after the Second World War. It would also bind organised labour ever-closer to the fortunes of the British Empire.

One sign of organised labour’s identification with Britain was its opposition to immigration and hostility to foreigners. In 1889 union leader Ben Tillett published a pamphlet, The Dock Labourer’s Bitter Cry, which carried this attack on the migrants:

The influx of continental pauperism aggravates and multiplies the number of ills which press so heavily on us… Foreigners come to London in large numbers, herd together in habitations unfit for beasts, the sweating system allowing the more grasping and shrewd a life of comparative ease in superintending the work.23

Tillett welcomed new immigrants at the dockside: ‘Yes, you are our brothers and we will do our duty by you. But we wish you had not come.’24 In 1894 and 1895 William Inskip and Charles Freak, officers of the National Union of Boot and Shoe Operatives, put forward resolutions against Jewish immigration — a ‘blighting blister’ upon the English worker — to the Trades Union Congress, and won.25

A Royal Commission on Alien Immigration of 1902 became the focus of a lot of hostility, as its hearings were reported in the press. Another Tory MP, William Evans Gordon, started the British Brothers League, which paraded in military fashion to protest against the influx of Jews.26

From all of this one might get the idea that the new unionism was a step backwards, hopelessly reactionary, sexist, and racist. But that would be wrong. This was a movement that fought and won rights for working people and defended their interests. The very idea of equality was defended and promoted by the labour movement. The new model unions took up the cause of the Bryant and May Match Women’s strike, and in 1925 Tom Mann helped organised a seaman’s strike that spanned the Empire, from London to Cape Town and Australia.

Bryant and May strike committee

The union movement was limited. It was limited to what was achievable within the relationship between capital and labour. Trade unionism was a bargain between two parties. Its achievements were what was possible within those terms. The gains for working people — English men for the most part — were circumscribed. The gains for working people were concentrated amongst those who were key to the relationship: industrial labourers. The enlargement of the wages, resources and rights of that one section marked out the difference between them and those women and immigrants who had not broken through. It was the greater equality afforded English working-class men that opened up the inequality between them and the oppressed.

After the ‘new Liberalism’, it fell to the wartime coalition of 1914-19, and then the 1940-45 coalition and the post-war Labour government of 1945-51, to consolidate the corporate system. War mobilisation into the army and the munitions factories greatly increased the demand for labour, both in the First World War, and in the Second. Between the wars, though, a terrible slump led to mass unemployment and the ‘hungry Thirties’.

Between 1914 and 1919, and again from 1939 to 1945, the emergency suspended all the normal rules of balanced budgets and free markets. Asquith’s Munitions Minister Christopher Addison relished the idea of directing the work of industry, and often leveraged workplace strife into a case for government taking over.27

Ruby Loftus screwing a breech ring, Laura Knight, 1943

As well as the great increase in the numbers working, there was a marked change in the make-up of the workforce. Millions of women were mobilised to work in munitions factories and on the land, wholly changing the sociology of work.

The use of women in munitions and engineering factories caused serious conflict. The Clyde Workers Committee led by Davy Kirkwood and John McLean trod a fine line between defending the rights of skilled workers and pushing for the exclusion of women. This was a live issue, and Charlotte Drake told a Conference of Women’s Organisations at the Board of Trade ‘that the men’s trade unions should be asked to take in women members and the women paid just as if they were men’. That way, she said, ‘there would be no reason to talk of the undercutting of the men by “women blacklegs”’.28

The movement towards a more corporate capitalism, though, would need a political vehicle that working people could trust, and that was not the Liberal Party. Politically, the new century saw the formation of the Labour Party. The party was formed on the initiative of the trade unions who created a Labour Representation Committee in 1905, followed in 1918 by a more strictly disciplined party. This was the party that would in the 1970s bring in equal opportunities legislation. Labour was in government in 1924, and 1940-45, and as a governing party between 1945 and ’51, from 1964 to 1970, and 1972 to 1979. Over that period British industrial relations were transformed with the creation (and eventual collapse) of the ‘tripartite system’ that institutionalised the partnership of capital and labour, with government, the third party, playing a role between umpire and organiser of industry.

Even more so than the ‘new Liberals’, Labour argued for the state to regulate private industry to defend workers. ‘The state assumed a new importance to the unions’, said J. T. Murphy: ‘State socialist ideas spread like wildfire. The demand for the nationalisation of this and that industry became popular.’29

It was not, however, until the Second World War that Labour’s instincts for a corporate capitalism could be put in motion. Even though they were junior partners in the wartime coalition, the Labour Party, by virtue of its intimate connection with the unions, carried great weight with working people. The Cabinet Office closely — and secretly — monitored popular opinion for signs of disaffection from the war effort, fearing the worst, but the results were largely approving. War mobilisation gave working people a feeling that they had a much greater stake in the fortunes of British society than they did in the era of mass unemployment.

During the war Ernest Bevin was Minister of Labour and second only to Churchill in the Cabinet. Bevin directed production, and cancelled the free movement of labour with ‘Essential Work Orders’, with a central register of all workers. Hours worked rocketed and consumption was cut by rationing — all of which could happen not just because of the widespread sympathy with the war, but also because working people were given a say in the organisation of work through Joint Production Committees. Workers and their representatives sat on Joint Production Committees, often with an official from a government department to meet the targets set in the Essential Work Orders. By the end of 1943, over 4000 Joint Works Production Committees had been established in the engineering and shipbuilding industries. Though the idea was that the Joint Production Committees were about increasing output and preventing bottlenecks, workers’ representatives often interpreted that to include their own goals. Canteens were a hot topic of discussion. But most of all skilled workers had their own views about how to do the work well, and were glad to be asked, having so rarely had their understanding of the processes recognised in the past. Under the common moral mission of winning the war, labour, management, and the government officials came close to embracing each other as partners. The wartime Joint Production Committee experience was the foundation of the corporatist, tripartite system of industrial relations in Britain, and a touchstone for most later iterations of that idea, right up to the mid-1980s.

Patriotism was re-worked to make the idea of Britain a popular, everyman version. Through the war, and in the peace that followed, the party of trade unionism was called upon to govern not just at home, but in the colonies, and to manage Britain’s relations to the wider world. Both the former trade unionists and the Fabian civil servants embraced the Empire project. So it was that the Labour Party objected to the clauses in President Roosevelt’s Atlantic Charter that promised decolonisation on the grounds that ‘the inhabitants of the African territories are backward’ and ‘not yet able to stand by themselves’. Labour’s ‘Marxist’ food minister John Strachey was blunt:

By hook or by crook the development of the primary production of all sorts in the colonial territories and dependent areas in the Commonwealth and throughout the world is a life and death matter for the economy of this country.

Or as one young Labour Tribune supporter asked, ‘what would happen to our balance of payments if we had to take our troops out of Malaya?’30

The post-war Labour government took one fifth of British industry into public ownership, including coal, steel, and rail — representing a quarter of the industrial workforce — as well as creating the National Health Service and extending compulsory state schooling from age 11 to 14. A significant share of the workforce was working directly for the state, and, though there was conflict between government managers and employees, workers, and in particular their unions, largely shared the identification with the ideal of nationalised industries.

Organised labour and officialdom

Workers’ representatives took part in a wide array of official bodies, panels and inquiries

• Wages Councils (operating industry by industry, 1945-93)

• National Wages Board (1950-65)

• National Board for Prices and Incomes (1965-70; policed pay norms and productivity agreements; separated into a Prices Commission and a Wage Board in 1970)

• National Joint Industrial Council (first created in 1919, these bodies were known as Whitley Councils in white-collar occupations)

• Advisory, Conciliation, and Arbitration Service (known by various names since 1960, as ACAS since 1975)

• Commission on Industrial Relations (1969‐74)

• National Industrial Relations Court (1971-74)

• Employment Tribunals (set up under the Industrial Training Act, 1964)

• National Economic Development Council (1961-92)

There were also industry-wide negotiation bodies, like the Railway Staffs National Tribunal, and factory-based consultations, and negotiations between unions and management.

There were as well a number of Royal Commissions dealing with trade unions over the years, including

• Royal Commission on Trade Unions (Lord Derby, 1867)

• Royal Commission on Labour (1894)

• Royal Commission on Trade Disputes (1906)

• Royal Commission on Trades Unions and Employers Associations (Lord Donovan, 1968)

And unions gave evidence to a great many Royal Commissions that they were interested in, such as the Royal Commission on National Health Insurance (1926); the Royal Commission on Unemployment Insurance (1931); and the Royal Commission on Mines (1906).

There was also the provision for Courts of Inquiry, like that into the newspaper dispute in 1955, into the power dispute in 1971, and into the dispute at Grunwick in 1977.

Trade unionists were drawn into a dizzying array of official bodies, which dealt with pay, prices, productivity, and industrial disputes.

Many of these bodies were set up with the express goal of disciplining labour, though where that was too explicitly so, as with the National Industrial Relations Court, the body failed. They were also very effective at drawing workers into the administration of capitalist industry. The legitimation of organised labour drew on 3000 full-time union officials and as many as 175,000 voluntary shop stewards. Though industrial disputes were commonplace, the conflict between the classes was largely contained in what the authorities often referred to as ‘constitutional’ actions. Employers told the Donovan Commission that the shop steward was not generally ‘trouble maker’ and ‘more of a lubricant than an irritant’.31 A Ford’s directive advised that ‘a shop steward holds his position by virtue of being a company employee and his first responsibility is to carry out the duties for which the company pays him’.32 Trade union officers could also serve on school governing bodies, as Justices of the Peace, as labour councillors, MPs, or even Ministers, and could take seats in the House of Lords and sit on government quangos.

Mark Freedland and Nicola Koutaris explain that between 1945 and 1970 the Department of Employment identified itself as ‘the seat and location of a tri-partite approach to the governance of the labour economy’, which rested on the ‘regulation of employment relations by collective bargaining of various sorts and at various levels between employers and organised labour, brokered and supported by the State’.33 In a Commons debate on the aerospace industry, Ealing MP Bill Molloy lauded the ‘record of British trade unionists in achieving industrial peace’, and Minister Gerald Kaufman agreed, saying that the British trade union movement ‘sets an example in patriotism’ — and they had a point.34

The new corporatist capitalism rested on a kind of social contract between private industry, organised labour, and government. The promise of job security and reasonable wages, coupled with extensive consultations and negotiations, cemented the deal. Managers took on the new arrangements and worked with them. The policy coalescence around full employment and corporatism was dubbed ‘Butskellism’ after its main proponents, the Tory ‘Rab’ Butler, and Labour’s Hugh Gaitskell.35

The recognition of the status of the core, skilled, and organised industrial workforce also meant by implication the subordinate status of those who were less organised, and whose skills were not certified. They were not covered by the same contract. The corporatist system institutionalised discrimination in employment. It created a hierarchy in employment where unskilled labour, immigrant labour and women workers were underpaid, aggressively managed, and insecure. The status of women workers in the new corporatist model was carefully set out for them, and given institutional shape by the post-war welfare system put in place after the Beveridge Report of 1944.

The Beveridge Plan

Central to the post-war compromise was the creation of the ‘welfare state’, set out in William Beveridge’s report, Social Insurance and Allied Services, in 1944. This was the bible for Labour Party supporters, the outline of a comprehensive welfare plan to create ‘freedom from want’.36 The plan was a great step forward for working people at the end of a terrible war, who had experienced the insecurity and hunger of the 1930s. ‘The aim of the Plan for Social Security is to abolish want by ensuring that every citizen willing to serve according to his powers has at all times an income sufficient to meet his responsibilities.’ But the responsibilities that Beveridge outlined were very different for men and women, seeing the latter first and foremost as housewives, whose responsibilities were in the home, while the former were breadwinners, who would be expected to provide for their wives.

According to the Beveridge Plan the population falls into four main social classes: 1) Employees; 2) Employers and the self-employed; 3) ‘Housewives, that is married women of working age’; and 4) the Unemployed.

Unemployment benefit stated that ‘there will be a joint rate for a man and wife who is not gainfully employed’; ‘every citizen of working age will contribute in his appropriate class according to the security he needs, or as a married woman will have contributions made by the husband’.37

Most married women have worked at some gainful occupation before marriage; most who have done so give up that occupation on marriage or soon after; all women by marriage acquire a new economic and social status, with risks and rights different from those of the unmarried. On marriage a woman gains a legal right to maintenance by her husband as a first line of defence against the risks which fall directly on the solitary woman; she undertakes at the same time to perform vital unpaid services.

Beveridge could be sure that his judgments were based on sound evidence:

At the last census in 1931, more than seven out of eight of all housewives, that is to say married women of working age, made marriage their sole occupation; less than one in eight of all housewives was also gainfully occupied.

Beveridge acknowledged that ‘there has been an increase in the gainful employment of married women since 1931’ — but that was to understate the importance of women workers in both world wars, and to take the contraction of employment in the interwar period, and the forcing of women out of the job market, as the norm. Beveridge went on to say that ‘even if a married woman, while living with her husband, undertakes gainful employment’, she is not in the same position as other employees, in two important ways. The first is that her work is ‘liable to interruption by childbirth’, and, he adds, ‘in the national interest it is important that the interruption by childbirth should be as complete as possible’. Second, the ‘housewife’s earnings in general’ are ‘a means, not of subsistence but a standard of living above subsistence’ — he does not say ‘pin money’, but the meaning is close to that.38

In Beveridge’s vision, the housewife’s ‘home is provided for her either by her husband’s earnings or benefit if his earnings are interrupted’. He criticised the ‘existing insurance schemes’ because they have ‘not recognised sufficiently the effect of marriage in giving a new economic status to all married women’. Evidence of the problem was that under the National Insurance scheme women ‘carry into marriage claims in respect of earlier contributions with full rates of benefit’ (though these were already disallowed under the Married Women’s Anomalies’ Regulations). Instead, Beveridge said, ‘the principle here is that on marriage every woman begins a new life in relation to social insurance’, and ‘she does not carry on rights to unemployment or disability benefit in respect of contributions before marriage’ — though she would receive a ‘marriage grant’.39

Beveridge knew that there would be criticism. ‘The decision to pay less than the normal rate of unemployment and disability benefit to housewives who are also gainfully employed is likely to be questioned’, he admitted. But ‘the case for it is strong’. ‘It is undeniable that the needs of housewives in general are less than those of single women when unemployed’ — because they would be dependent on their husbands. Given the maternity benefits and marriage grant, thought Beveridge, ‘housewives cannot complain of inequity’. Rather, he says, ‘Taken as a whole, the Plan for Social Security puts a premium on marriage, instead of penalising it’, and ‘the position of housewives is recognised in form and substance’.40

The Beveridge Plan was rightly celebrated for the commitment to social security it represented. But even as the welfare state offered help, it enshrined the role of the housewife in the organisation of the economy as a distinctive class, rewarding marriage and penalising those married women who worked, on the assumption that they would be dependent upon a male breadwinner.

Not just welfare law, but tax law too, institutionalised gender segregation. Before the Second World War only around 20% of the population paid tax, but alongside National Insurance, workers were subject to ‘pay-as-you-earn’ income tax, bringing the tax base up to 12 million. The tax system aggregated married couples’ incomes and gave a married person’s tax allowance that assumed women’s work was secondary, and incentivised the nuclear family. From 1969 married couples got tax relief on mortgages (Mortgage Interest Relief at Source), and from 1945 they got child benefits. There were benefits for lone parents, including free school meals, though these came with a great deal of social shaming. From 1948 the National Health Service took on the policy of ‘confining’ women in hospital wards for the last weeks of pregnancies to shield them from work and to cut infant deaths. A division of labour based on gender was written into the welfare state, and was a guide to employers.

Segregated workforce

After the war, women’s employment grew steadily, much more than Beveridge had anticipated. But the tenor of government policy mirrored the attitude of both employers and trade union leaders, that women had a subordinate place in the jobs market. One clear sign was that the growth in the numbers of women in work went hand in hand with sex-segregated workplaces. At Ford UK’s plant in Dagenham there had since the war been many women working alongside men on the assembly line, but a big shake-out in 1951 forced them out. Afterwards, women at Ford worked stitching seat covers with sewing machines, or in the canteen. Women worked in biscuit factories, like Peek Freans in Bermondsey, making sweets at Rowntree’s in York, and in the clothing trade working sewing machines. Many worked, too, as nurses in the new National Health Service — 194,900 in 1952, alongside doctors who were almost all men.41 Researcher Carolyn Vogler found that gender-segregated workforces are associated with more traditional roles in the home: ‘men living in households with a more traditional division of labour were more likely to be working in segregated jobs’.42

Women on Cadbury’s production line

In the post-war expansion of the economy, employers took advantage of the low wages women were expected to work for — expected by Beveridge and the Labour government, amongst others. With this outlook common in the labour movement the unions failed to recruit. Trade union membership rose from 7.8 million in 1944 to 10 million in 1966, but throughout the share stayed at four fifths men to one fifth women. Around half of all men in work over those years were members of a union, but only one quarter of all women were.43 As was common, the National Union of Tailors and Garment Workers negotiated a differentiated pay rise of 5d an hour for men and 4d an hour for women in 1969 — even though 93,000 of its 111,000 members were women.44 It was common up until the 1990s to find largely female workforces represented by male trade union convenors, and often male shop stewards, too.

In 1948 the British Cabinet was looking in alarm at the arrival of 492 Jamaicans on a ship called the Empire Windrush, bound for Tilbury. The Cabinet Economic Policy Committee regretted that the migrants were ‘private persons travelling at their own expense’ and that they could not be turned back, though they did look at whether they could be sent on to East Africa. The committee asked for a report on ‘the incident’ from Colonial Secretary Arthur Creech Jones, and asked how any more like it could be stopped. Creech Jones accepted that the arrival was a ‘problem’ but that as a ‘spontaneous movement’ the government did not have the ‘legal power’ to stop it. Instead they would have to take special measures to manage the migrants.45

John Hazel, Harold Wilmit & John Richards arrive at Tilbury docks from the Caribbean on the ex-troop ship Empire Windrush (1948).

Britain’s post-war economy grew at a healthy average of 3% per year between 1948 and 1973. Demand for labour tightened and for the first time significant numbers of immigrants came from the British West Indies, and from the Indian sub-continent. They were joined by Asians forced out of Uganda and Kenya in the 1960s. More than a quarter of a million black West Indians arrived in Britain between 1953 and 1962, along with 143,000 from India and Pakistan.

The legal and moral basis for the right of migration to Britain was set out in the 1948 Nationality Act. The British Empire had been re-organised as a Commonwealth after the war. Where the Empire nominally had common citizenship, each country was allowed to make their own laws afterwards, but Britain at first operated something like an ‘open door’ in recognition of the rights of former subjects. Practical restraints made migration between Commonwealth countries rare, except where there was labour recruitment.

Booming Britain took on West Indians and Asians as nurses and midwives, on the buses and the Underground, as labourers, as cleaners, and in catering. West Indian teachers were called on to fill places in the new Secondary Modern schools, after the school leaving age was raised. Indians and Pakistanis found work in textiles in West Yorkshire and Lancashire. Indian doctors found work in the new National Health Service, as did West Indian and some Asian nurses. Most jobs that migrants filled were unskilled, though many who came had good training and education.

From the outset the political establishment were nervous about the new migrants. When the Windrush arrived at Tilbury in 1948 a group of Labour MPs wrote to the Prime Minister that ‘an influx of coloured people domiciled here is likely to impair the harmony, strength and cohesion of our public and social life and to bring discord and unhappiness to all concerned’. After the Attlee government’s reaction, the Conservative leader, Winston Churchill, planning the 1955 Conservative Manifesto, told the Cabinet that the best slogan would be ‘Keep England White’.46 Birmingham Labour MP Roy Hattersley argued that ‘unrestricted immigration can only produce additional problems’. In 1964 he thought that ‘we must impose a test which tries to analyse which immigrants are most likely to be assimilated into our national life’.47

Caribbean nurses

In 1949 the Ministries of Health and Labour, together with the Colonial Office, the General Nursing Council, and the Royal College of Nursing, started recruiting in the West Indies. By 1955, 16 British colonies had set up selection and recruitment schemes for the NHS.

In its first 21 years, between one quarter and one third of all NHS staff were recruited from overseas.

By 1954 more than 3000 Caribbean women were training in British hospitals, rising to 6,450 in in 1968.

In 1969 the Nursing Times pointed out that only 5% of overseas recruited nurses were reaching the top grades of the profession.

— Ann Kramer, Many Rivers to Cross, London: The Stationery Office, 2006

Government hostility was in time mirrored by race attacks in Notting Hill and the Midlands in 1958. These disturbances were taken as a justification for the first in a succession of laws to restrict immigration, the 1962 Commonwealth Immigration Act. Under the Act, a set number of vouchers were issued through which migrants could enter, therefore controlling the numbers coming into the country from each Commonwealth country. More laws were passed in 1968 and 1971, all aiming to ‘tighten’ controls on immigration.

The practical impact of the immigration law was that it established a hierarchy in which black people were of lower status than those who were white. The hierarchy was ideological in that it embodied racial superiority. It was also practical in that black people were subject to treatment by public authorities that white people were not. Black workers were investigated by an Illegal Immigration Intelligence Unit of the Police Force, the immigration police, which raided scores of workplaces from its foundation in 1973. At the same time police paid special attention to younger black men on the streets, searching and arresting them for public order offences. Even schools were unofficially segregated, by local catchment areas, and by excluding many West Indian boys under disciplinary rules; in 1986, Calderdale Education Authority was investigated by the Commission for Racial Equality for keeping Asian children out of mainstream schools, by testing their language proficiency and pushing them into special language units.48 When Bernard Coard wrote a small booklet titled How the West Indian Child is Made Educationally Sub-Normal in the British School System, ‘the whole community’ was ‘galvanised’. (Schools today show some evidence of segregation by choice.)49

Discrimination against black people shaped their lives and the work they did. Overall, the numbers working in manufacturing fell by 745,000 between 1961 and 1971; but the number of manufacturing workers born outside Britain rose by 272,000. By 1971 79% of West Indian men and 78% of Pakistani men of working age were manual workers, compared to 50% of working men as a whole. Three quarters of immigrants’ wives worked compared to just 43% of all married women.50

A third of all the workers at the Courtaulds Red Scar mill in Preston, by 1964, were Asians: ‘Two departments of the mill were wholly immigrant, organised in ethnic work-teams under white supervisors.’51 The authorities’ differential treatment of black and Asian people in Britain made it easier for employers to treat them differently, too. One Asian Ford worker described the assembly line at Langley:

[W]alking along the Body line at Langley truck plant, on either the day shift or the night shift, is like walking around the world. The bottom section is where the work is hardest and there is hardly any overtime: the workers are mostly Asian with only the occasional white and West Indian worker. The middle section involves less arduous and slightly more skilled work. There you will see a mixture of African, West Indian, Asian and white workers. The top section is the repair area, an area where the pace of the work is not determined by the speed of the line, and where there is the most overtime. The area is predominantly white.52

Ford were well known for taking on black workers, and in their southern plant at Dagenham, West Indians were moving up the skills grade. Ford’s race relations would become a battleground for many years.

In 1982 Leila Hassan looked at ‘ancillary work in the National Health Service — catering, portering, washing up, cleaning jobs and laundry jobs done by some 70,000 blacks (mainly women), a third of the total workforce’. The women she talked to told her:

The government and ministers know that ancillary workers are more low paid than any other workers in the NHS or in the country and we are living below the poverty line, and never has the government offered us anything.

They added, ‘it is not the nurses doing the dirty jobs, it is the ancillaries, and without us the nurses couldn’t function, it’s we keep the nurses’.53

West Indian nurses were mostly taken on at the less qualified State Enrolled Nurse position while the better paid State Registered Nurse position was kept for whites. ‘The NHS reminds me very much of a colony in the way it’s run’, one nurse told Beverly Bryan and her fellow researchers: ‘the white sister will act as manager, organising the work for her black nursing staff, and then spend the morning sitting in the office’.54

Black workers were generally taken on in subordinate roles and discriminated against at work. Trade union offices would insist that they were ‘colour blind’; but they were also patriotic for British industry in a way that their officials took to mean ‘British jobs for British workers’. In 1965 a local union branch opposed jobs for black nurses at Storthes Hall Mental Hospital; the following year Asquith Xavier was barred from working at Euston station under an agreement between the Staff Association and the employers — colour bars were operating at Camden and Broad Street, too. In Keighley in 1961, engineers struck when two Pakistanis were put to work, and in the same year shop stewards at Alfred Herbert Machine Tools sought assurances from management that black workers would not be promoted.55

The problems of race and sex discrimination were important markers of the limits of the corporate society, of the outer boundaries beyond which the social contract no longer applied. But these problems were not its core dynamic. The basis of the system was the relationship to organised labour. It was that relationship that was tested to destruction in the 1970s and 1980s. The crisis, and the subsequent dismantling of the corporatist system, would shake up all relations.

In the 1960s Britain’s competitiveness with its industrial rivals was slipping, and its profit rates were under pressure. British workers had been driven hard to produce more in the post-war years. But ever-greater capital investments gave, to the frustration of the employers, a declining rate of return. Labour-saving machinery increased the product efficiency of industry, but in lowering prices reduced profit margins too. The National Board for Prices and Incomes saw the barrier to increased profits as workers’ reluctance to raise productivity, a view that echoed managers’ resentment at the imagined encroachment on their right to manage under agreements with the unions.

Over the years from 1965 to 1979 governments and employers tried different ways to address what they saw as a ‘productivity gap’ through the corporate system they had built. Harold Wilson’s government tried to enforce a wage freeze in 1966 alongside increased productivity. Then Labour tried to stop unofficial strikes with their ‘In Place of Strife’ white paper: proposals to manage industrial conflict through a quasi-legal framework. Labour’s working-class supporters were put off, and Edward Heath’s Conservative government was elected — only to try put in place a yet more coercive Industrial Relations Act. The attempt to impose pay restraint and limit industrial conflict through the corporate system only tended to provoke a greater reaction. Using it to restrain labour militancy and force up productivity strained the corporate system to breaking point.

The first sign of the crisis of corporatism was a rising crescendo of industrial conflict, and unnervingly for the system’s defenders, of unofficial strikes, rising to 24 million in 1972. According to the government white paper, ‘In Place of Strife’, ‘95 per cent of all strikes in Britain were unofficial and were responsible for three quarters of working days lost through strikes’.56

Militant strike action was always a possibility in a system that relied on negotiating agreement between employers and labour. The subjective collaboration of the workforce was what the system was there to engage, so the prospect that it might be withheld was a perennial danger. Institutionalised conflict might break out of its boundaries. The incorporation of the union leadership in the management of British industry put them in the front line of the conflict. They were at once trying to hold the support of the union members, and put forward the case for the terms they had negotiated with management. Opposition to the leadership opened up. In many instances, the local shop stewards became an alternative leadership, leading strikes that were not sought, and often not supported by the convenors and union leaders. On other occasions ad hoc rank-and-file movements challenged the stewards as well as the convenors.

Employers were not surprisingly outraged at what they called ‘unconstitutional’ action. They felt that they had already conceded more authority to unions than they would have liked, and were angry to find that the union leaders could not deliver their members’ support. Employers, though, had provoked the conflicts, driving workers to increase productivity, and trying to hold down wages while putting up their own prices. The workplace relationship was only superficially one of agreement. Agreements and negotiations would hardly be necessary if the workers’ interests truly coincided with their employers’ interests.

Strike for the ‘Pentonville 5’ dockworkers jailed for picketing

Baron Geddes of Epsom had been General Secretary of the Post Office Workers’ union from 1944 to 1957, and President of the Trades Union Congress in 1955. On 18 March 1969 he told the House of Lords that ‘the men who ran the trade union movement… could be called patriots’:

They believed that they supported the Government of the day, not because they were, in the Left-wing words, ‘capitalist lackeys’ but because they believed that the good of the country in the long run, in the long term, was for the good of their members. It seems to me to-day that we cannot be so certain that that is true.57

Women were also taking strike action. In 1968 187 women working as machinists making seat covers at Ford went on strike to get their jobs regraded. Around that time many women were taking part in the workplace disputes that were raging, such as the London night cleaners’ fight for union recognition, the disputes of 20,000 Leeds clothing workers, and women taking part in the teachers’ strike. The Ford machinists’ strike set down the ideal of ‘equal pay for equal work’.

The 1974-79 Labour government pushed the corporate system to its limit. The social contract between organised labour, employers, and government was used yet more forcefully to hold down wages and boost productivity. In its programme of 1973 Labour argued for ‘a great contract between government, industry and trade unions, with all three parties prepared to make sacrifices to achieve agreement on a strategy to deal with the problems’. The trade union leaders agreed a wage rise limit of £6 in 1975, followed by a second phase of limit of 4.5%. The ‘third phase’ was imposed against an all-out strike by firefighters in 1977. The view of the trade union movement was that government had forfeited their trust by its use of legal compulsion in labour organisation.58

The announcement of another 5% limit — ‘Phase 4’ — in 1978 provoked an open rebellion. The low-paid workers of the National Union of Public Employees struck out rubbish collection and even burials; railway workers and road haulage drivers struck. More people were out on strike than in 1972: 4.6 million, with a loss of 29.4 million working days.

Engineers’ leader Reg Birch looked back over the record of Labour’s ‘In Place of Strife’, Health, and Industrial Relations Acts, ‘the various forms of wage restraint and compulsion’: ‘After 33 years of the oppression of the working class by social democracy there is now a bursting out.’59 The feminist Beatrix Campbell took an altogether different view. To her it seemed that the revolt was against the egalitarian pay award under the Social Contract, an across-the-board £6 per week, that was sabotaged when ‘the redoubts of macho Labourism had mutinied and insisted on the “restoration of differentials” — the gap between skilled, unskilled and women’.60

The crisis of the corporate economy was felt sharply by ethnic minorities. Unemployment rose overall, but black unemployment climbed even faster. Black people made up 2.3% of the unemployed in 1973, but by 1982 that number was 4.1%. For a social group that was heavily dependent on manufacturing and the public sector, the contraction of both those spheres was a blow. Unofficially trade union branches often adopted the line ‘last in, first out’, meaning that where there were lay-offs, black workers would be first. Black children were demotivated at school by the limited job prospects of their older peers, and by the low expectations of their teachers. Asian workers were militant in defence of their jobs and conditions. In the Midlands Motor Cylinder Company in 1968, at Mansfield Hosiery Mills in Loughborough in 1973, in the Imperial Typewriters strike in Leicester 1974, and in the strike by photographic processing workers at Grunwick’s in 1977, they took action against employers. These strikes were all provoked by bullying management, and the promotion of white workers over Asians. Often the local union negotiators dismissed the workers, as TGWU negotiator George Bromley did when he complained that the Imperial Typewriters employees ‘have not followed the proper disputes procedure’, and ‘have no legitimate grievance’.61

With greater pressure on household budgets in the later 1970s women were taking on more work, often part-time. Economic pressures, though, were leading to more reactionary ideas. The Sunday Times editorialised that ‘unemployment and inflation have made it imperative to convince women that their place is in the home because the country cannot afford to employ them or pay for the support facilities they need’.62

The strike wave of the low-paid was called a ‘peasant’s revolt’, and also a ‘winter of discontent’, and the widespread disaffection saw Labour lose the 1979 election to a Conservative government committed to dismantling the post-war consensus.

Soon after winning the election in 1979, Margaret Thatcher signalled that the days when government would broker talks between industry and unions were over, saying there would be ‘no more beer and sandwiches at Number Ten’. The Labour government, she said, had offered ‘the joint oversight of economic policy by a tripartite body representing the Trades Union Congress, the Confederation of British Industry and the Government’. But ‘we were saved from this abomination’, which she called ‘the most radical form of socialism ever contemplated by a British government’; corporatism and the tripartite talks between government were a trap. As Neil Millward et al summarised:

The government’s aim — highly controversial at the time — was to weaken the power of the trade unions, deregulate the labour market and dismantle many of the tripartite institutions of corporatism in which the trade unions played a major part.63

Chancellor Nigel Lawson, limiting the powers of the wage councils, said that in a ‘free society it is plainly a matter for business and industry itself to determine rates of pay’.64 As Linda Dickens and Alan Neal explain, ‘institutional arrangements seen as underpinning… structured collective bargaining and/or imposing rigidities on the operation of the free market were eroded or ended’.65 Employment laws were passed in 1980, 1982, 1984, 1986, 1988, 1989, 1990, 1992, and 1993 — all limiting the power of trade unions to strike, making them liable for company losses, outlawing the ‘closed shop’ agreements with employers, and enforcing ballots before strike action could be taken.

With the encouragement of the Department of Trade and Industry, British industry set about a marked reorganisation. Not only were 60% of government holdings privatised, but many larger and more established industries were slimmed down — some, like shipbuilding and coalmining, to the point of extinction. Industries were restructured, often contracting out all but their core activities, leaving employees to compete for their old jobs in new service-sector businesses. Many companies de-layered and down-sized their workforces, taking advantage of anti-union laws. Bypassing union negotiators, employers made their own contracts with individual employees. Workforces were encouraged to agree ‘flexibility’, working hours that suited their life obligations or, more often, the needs of the employers. Many new contracts were for part-time and temporary positions. There would be ‘no more job for life’, workers were told. One change that would prove important for the spread of equal opportunities policies was the growing appeal of the paradigm of ‘Human Resource Management’, ‘the banner under which increasing numbers of employee relations specialists marched’, according to Neil Millward. Human Resource Management would mean a much more individuated relationship between employee and employer, but also one that was all procedure, and so depersonalised.66

Though they claimed to be taking the state out of industry, and out of wider society, the Conservative government used state power extensively. Police power and the law courts were used to prevent workers from striking and protesting, having outlawed ‘secondary’ picketing and mass picketing. Between 1980 and 1988 520 separate acts of parliament were made law, along with 18,893 statutory instruments — around 7000 pages of legislation every year; civil liberties were reined in over everything from horror films on video, to schools’ treatment of homosexuality, dangerous dogs, football fans, and raves.67

Most of all, though, the meaning of trade union reform and the effective end of the tripartite system was that the national consensus that had been established in the post-war period was ended. The end of consensus had profound effects on social attitudes, leading to a marked individuation and even a disaffection from public life. One of the more pointed features of the Conservative governments in the years from 1979 to 1997 was an appeal to a robust patriotism. But in a sense, that appeal to national sentiment was a sign that its substantial basis had been eroded. The post-war consensus bound people to the national project, through a wide span of bodies: trade unions, mass political parties, municipal councils, in addition to the charities, church groups, and women’s institutes that appealed to the more middle-class Britons. Most of those groups and clubs withered as the government tore up the old social contract. As ‘the Nation’ had less and less substance, the establishment appealed to it even more.

Targeting immigrants

One dramatic focus of the stridently national rhetoric that the government adopted in the 1980s was a renewed focus on restricting immigration. Margaret Thatcher had said at the election that many people felt ‘that this country might be rather swamped by people of a different culture’. A new Nationality Act of 1981 limited the rights of those citizens of the Commonwealth, and William Whitelaw said the law was ‘to dispose of the lingering notion that Britain is somehow a haven for all those whose countries we used to rule’.68 The immigration police were encouraged to re-double their efforts and in 1980 there were 910 removals and 2,472 deportations, around twice the amount in previous years, and a rate that was kept up through the 1980s. Newspapers sent photographers to the landing gates for flights coming in from India and Pakistan to illustrate headlines like ‘they’re still flooding in’ (Evening Standard). ‘In former times such invasions would have been repelled by armed force’, reported the Daily Mail. When Tamil refugees arrived from Sri Lanka in 1985, Home Secretary Leon Brittan said they were a threat to British workers’ jobs and living standards. The Financial Times trumpeted that ‘the last thing the country needs is a flood of new immigrants’.69 Official sanction for anti-immigrant feeling encouraged a long spasm of race attacks against brown and black people living in Britain.

In March 1986, 36 police officers raided the British Telecom offices in the City of London, interrogating cleaning staff on their legal status, with the collaboration of the BT managers. It was just one of hundreds of ‘fishing raids’.70 Black and Asian people were asked to show their passports at work, and at hospitals and unemployment benefit offices. People deemed ‘illegal’ under the nationality laws were subject to detention and deportation.

It was not just immigrants from the Indian sub-continent who were caught out by the renewed emphasis on Britishness. West Indians stood out as far as the authorities were concerned. Metropolitan Police Chief Kenneth Newman said in 1982 that ‘in the Jamaicans you have people who are constitutionally disorderly… it’s simply in their make-up’.71 The year before, London police had launched a campaign against ‘street crime’ called ‘Swamp 81’, under which they stopped and searched scores of young black men in Brixton in South London. The operation provoked a riot that lasted two days. A sustained campaign to criminalise black people provoked disturbances in Toxteth, Liverpool, and Bristol in that same year. In 1985 police assaulted Cherry Groce in a raid nearby the Broadwater Farm that ended in prolonged rioting in which Police Constable Kenneth Blakelock was killed. Winston Silcott, imprisoned for the killing, was vilified as the face of hatred on the front cover of the newspapers, though later his conviction was quashed.

Britain’s unhappy row about what was and what was not ‘British’ was a sign that the old social compact had broken down. Without many positive gains to engage their citizens, the elite chose to define the nation negatively, targeting foreigners with darker skin. The consequences for equality of opportunity seemed very slim. According to Sociologist Yaojun Li,

in 1981, unemployment rose to 10% for White men, but jumped to 26% for Pakistani/Bangladeshi men. When the recession was at its highest in 1982, Black and Pakistani/Bangladeshi men’s unemployment rate reached nearly 30% as compared with only 12% for White men.72

The impact of a patriotic Britain was destructive, but it was also limited in its appeal to a nation that felt less and less engaged.

Alongside the emphasis on nation, Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher thought that her government ought to be ‘concentrating on strengthening the traditional family’, and ‘never felt uneasy about praising “Victorian values”’.73 In 1979 the new Conservative Minister for Health and Social Security, Patrick Jenkin, said that ‘Mothers should be encouraged to look after their children full-time instead of going out to work’. According to Jenkin, ‘the increasing turbulence of modern life, with rising crime, industrial disruption, violence and terrorism is rooted in the separation of children from their parents’.74

Legislation cutting social security entitlements to under-25 year-olds was based on the idea that families would support young people for longer. Cuts in many services assumed and depended upon the work of families — overwhelmingly of wives and mothers — to make up what was taken away. So the limited spending on care for the elderly assumed that women would take up the slack.

In 1988 it seemed to be a real possibility that abortion rights would become more limited. Liberal MP David Alton’s Private Member’s Bill (which was ultimately unsuccessful) would have outlawed late-term abortions. At Dame Jill Knight’s urging a clause was added to the 1988 Local Government Act forbidding teachers from saying that homosexual relations could be ‘a pretended family relation’. The restriction, first demanded by the Parents’ Rights’ Group in Haringey, passed.

Margaret Thatcher

That social compact that had been made in the post-war years between capital and labour, brokered by the state, was breaking down in the 1980s. The circumstances suggested that the times were hostile to equality in the workplace.

The Conservative governments of 1979-83 and 1983-87 kept up a strongly traditionalist and xenophobic rhetoric, backed up with laws hostile to migrants and women. The end of the industrial consensus seemed to signal an even harsher iteration of the gender and racial inequality than before. As things turned out, though, other changes were pulling in an altogether different direction.