The Equal Opportunities Commission

‘Equal pay is the oldest wage claim in the history of the British trade union movement’, the TUC President John Newton told its first ever equal pay conference in 1968.1

The call for equal pay was first made by matchgirls’ strike leader Annie Besant in the 1890s, and raised at trade union congresses many times since. In the Second World War the claims made by Esther Lahr and others in the Transport and General Workers Union were reported in the papers: ‘The government was today urged to give women the same pay and conditions as men.’2 After the war the Trades Union Congress took a traditionalist line, arguing that

the home is one of the most important spheres for a woman worker and that it would be doing a great injury to the life of the nation if women were persuaded or forced to neglect their domestic duties in order to enter industry particularly where there are young children to cater for.

The TUC agreed to the Labour government’s closing wartime nurseries, and said that equal pay was ‘inappropriate at the present time’ because of ‘the continuing need for counter inflationary policies’.3

A Civil Service Commission of 1948 tentatively suggested equal pay, while worrying about the ‘psychological impact’ on men. The women on the Committee, though, put in a minority report saying ‘the claims of justice between individuals and the development of national productivity point in the same direction’ — equal pay.4 By 1955 staff unions had negotiated equal pay in the civil service and in the Post Office, though inequality in grades and promotions was untouched.

In the quarter century after the Second World War the economy grew strongly and more women went to work. Between 1964 and 1970 women made up 70% of the growth in trade union membership. The shop workers’ union USDAW won the Trades Union Congress to a resolution for equal pay in 1963, leading to an Industrial Charter for women that called for equal pay, equal opportunities for training, re-training facilities for women returning to industry, and special provisions for the health and welfare of women at work.5 The following year the Labour Party pledged new laws on equal pay.6 In 1965 the TUC resolved

its support for the principles of equality of treatment and opportunity for women workers in industry, and call[ed] upon the General Council to request the government to implement the promise of ‘the right to equal pay for equal work’ as set out in the Labour Party election manifesto.

The unions’ attention to equal pay and sex discrimination helped them to recruit more members. Between 1968 and 1978, the number of women in the public employees’ union (NUPE) more than trebled, that of the local government officers’ union NALGO more than doubled, that of the health service union COHSE quadrupled, and the white-collar workers’ union ASTMS multiplied its female membership by seven times.7

The changing mood over equal pay spread to the professions, too. Baroness Seear had worked at the Production Efficiency Board at the Ministry of Aircraft Production in the Second World War, having been a personnel officer at Clarks before. Afterwards she taught at the London School of Economics, where she championed women’s employment, writing in 1964 that ‘if we want to find an unused reserve of potential qualified manpower it is among women that it can most easily be discovered’.8 More women were going on to higher education courses, where some were founding women’s groups, like the London Women’s Liberation Workshop, reading Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique and Germaine Greer’s The Female Eunuch, and publishing the magazine Shrew. In the 1970s, women at Ruskin College organised the first Women’s Liberation Movement conference.

The events that led to the two laws on Equal Pay (1970) and Sex Discrimination (1975), creating the Equal Opportunities Commission, can best be understood in the context of the heightened social conflict of the day. The Labour governments of 1964-71 and 1974-79 were in the grip of a revolt from below embodied in a number of unofficial strikes. That the focus of sex discrimination law was pay was because of inequality, and also because pay was the issue of the decade.

Women’s Liberation Movement conference, Birmingham, 1978

Women played a big part in the militancy of the late 1960s and ’70s. They were active in strikes at Rolls Royce and Rootes in 1968, of the London Night Cleaners over union recognition in 1970, and in the teachers’ strikes as well as the Leeds Garment Workers’ strike of that year. The following year saw a London telephonists’ pay dispute. In 1972 women joined the occupations of Fisher-Bendix on Merseyside and Briant Colour Printing in London. Women at Goodman’s, part of Thorn Electrical Industries, successfully struck for equal pay. In 1973 hundreds of thousands of hospital workers, mostly women, went on their first ever national strike. In the same year 200 women in GEC, Coventry, struck for eight weeks over piece rates.9 Many of these strikes were backed by an umbrella group, the National Joint Action Campaign for Women’s Equal Rights. The most important of these conflicts was the strike by women machinists, stitching the upholstery in Ford’s works in Dagenham, East London, which is generally credited with changing the law.

The Labour Minister responsible for employment in the 1964-70 government was Barbara Castle, who would propose the equality legislation. Her main role, though, was to face down the trade union demands of men and women. Some in the government, like Peter Shore and economic adviser Tommy Balogh, came to think that if socialism meant a planned economy, then that should mean that rates of pay should be set by the state, too. Others like Jim Callaghan, who had been a trade union leader before he was a Member of Parliament, argued for ‘free collective bargaining’ against state intervention in the rights of trade unions to strike their own pay deals. The different sides of the argument were not exactly clear at first, and did not fit with the obvious ideas of ‘left’ and ‘right’ in the party. Barbara Castle, having come from the left, was between the two positions, but as the Minister she argued the case for an incomes policy, setting her at odds with the trade unions, usually in the person of their largely male leaders.

The incomes policy that Castle fronted, ‘In Place of Strife’, hurt her standing in the labour movement, casting her as the mean witch holding down workers’ pay. She had to defend government intervention against the trade unions, whittling away at her socialist credentials. The strike at Dagenham was ‘the dispute that marked the start of her disenchantment with trade unions’.10

The women struck at Ford Dagenham over the way their work had been graded, not specifically about equal pay, though the way that management had not recognised their skills was discriminatory. The strike was a blow to Castle because it came just as Ford and the unions were signing off on a ‘no strike’ deal that the government had put its weight behind. Castle called the union leaders in to talk about what had gone wrong, and ‘asked them what they could do to help get the women back to work’. In her diaries Castle was scathing when the engineering leader Reg Birch told her ‘equal pay was the policy of his union’. For Castle, the issue was the agreement with Ford, while Birch insisted that ‘new issues have been thrown up since it was signed’. Castle thought ‘this, of course, is a recipe for anarchy’.11

Though her first thought was to end the Dagenham women’s strike, Castle was uneasy. She sent the whole issue back to a Court of Inquiry, but that was taking a long time, while the strikers were getting good press. Seeing that things were moving too slowly, Castle writes, ‘I blew my top, saying emphatically, “This is where I intervene”.’ From her office, she twisted Ford’s arm to regrade the women, which, while hard for them, was not as costly as a long strike would have been. Calling the strikers in, Castle saw the public relations boost.

‘She herself sat in the middle of the sofa and gathered them around a large, mumsy tea-pot’, writes biographer Ann Perkins: ‘The photographers came in early, in case the talks went too badly for pictures to be taken later.’12 As Castle wrote at the time,

The best part of it from my point of view was the genuine rapport I had established with the women. I think I managed to make Government look again as if it consisted of human beings and not just cold-blooded economists.13

Later she bumped into one of her more radical parliamentary colleagues, who had been critical about the ‘In Place of Strife’ white paper: ‘Glowing congratulations from Eric Heffer about the Ford settlement’, she writes, as he says: ‘This is the kind of intervention I believe in.’14 Castle found that that the equal pay issue was one where an incomes policy was popular. It was also one where the government had moral authority over the unions, not the other way around.

Soon after the Dagenham strike, another equal pay issue blew up in negotiations between the engineering employers and unions. The women’s pay grade had been left to the end of the talks. The employers were not giving much. The engineers were threatening strike action to get the women more pay. In Castle’s eyes the extravagant claims of the men were to blame: ‘the unions had always understood that there would have to be some concessions by them on the women’s differentials if they pushed up the skilled rate’. Instead, the unions hoped she would lean on the employers to give more. She wrote that she ‘well and truly blew my top, telling them icily that I had been waiting for a long time to hear when they were going to start talking about the women and was shocked to find that they had left it to the very end’.

Turning on the union side Castle was pleased that she had started a ‘ding dong row’ between engineers’ leader Hugh Scanlon and the only woman on the negotiating team Marion Veitch. She notes that Scanlon was ‘clearly nervous at the success of my attempt to turn the tables on him’. Castle boasts that she has stopped a strike in favour of more pay for the women, and persuaded the men to take a smaller rise.15

Around this time Barbara Castle was facing the full fury of the unions over the ‘In Place of Strife’ white paper, with its proposals limiting union action, with a cooling-off period, compulsory strike ballots, and penalty clauses for unofficial strikes. Though some radicals, even Tony Benn, backed the proposals, the campaign against them picked up steam.

In 1969, as the Cabinet prepared policy ahead of the Labour Party Conference, Castle ‘said that my paper on the Industrial Relations Bill could wait but could we clear equal pay urgently?’ At the conference, Castle was pleased to find Transport and General Workers Union leader Jack Jones livid about ‘my announcement about equal pay which robs him not only of a grievance against the Government, but of some of the leadership on industrial issues which, I am now convinced, he wants exclusively concentrated in the hands of the unions’. Staking out new ground on women’s pay, she found, played up the union leaders’ weakness on the issue. Foundry workers’ leader and Labour Party chairman Willie Simpson congratulated Castle on the equal pay proposal, saying ‘the equal pay debate at the TUC… made me sick’: ‘As you say, they’ve been talking about it ever since 1880 and never done anything about it themselves except criticize.’16

In 1969 Castle was talking to a delegation from the TUC, led by Vic Feather. Castle again grabbed the moral high ground by goading the union leaders for leaving women in the lurch: ‘talking of job opportunity, when were the unions going to give a lead – on allowing women bus drivers, for instance? It’s time we had some militancy, I gibed.’17 While the incomes policy in the ‘In Place of Strife’ white paper was made unworkable by union opposition, the more positive incomes policy of equal pay became law in the last months of the Wilson administration. Its provisions were delayed until 1976 to give employers time to phase in the changes.

On its own the Equal Pay Act would not work. Baroness Seear’s research project on the impact of equal pay legislation found that in half of the organisations she surveyed ‘action was taken to minimise the employers’ obligation’: ‘Such minimising action included the creation of new all-female grades, the retitling of jobs and undergrading job evaluations exercises.’18 Equal pay rules meant that women doing ‘like work’ to men would have to be paid the same. But if men got the promotions, or were put on different grades, employers could dodge equal pay; and if women were not given the chance to get the jobs men did, equal pay would mean nothing. Like the Race Relations Act (1976), the Sex Discrimination Act outlawed direct discrimination in hiring, promotion, training, and treatment, alongside the ‘equal pay’ clauses of the 1970 Act.

The 1976 Act also set up the Equal Opportunities Commission — again, like the Commission for Racial Equality, an arm’s-length independent government agency. The Equal Opportunities Commission had powers to help individuals to seek redress under the Acts at an industrial tribunal. The Commission also had power to investigate organisations, and to issue ‘discrimination orders’ telling them to fix discriminatory policies, and monitoring them.

For its first ten years the Commission was led by miner’s daughter Betty Lockwood, who had studied at Ruskin College before becoming a Labour Party organiser. Her second-in-command was Elspeth Howe, who stood down in 1980 around the time her husband Geoffrey became Chancellor of the Exchequer in the new Conservative administration.

The new organisation started with a modest grant of £850,000, rising to £2.5 million in 1980, when there were 170 people working in its main office in Manchester.19

In 1977 the Commission pursued actions against ‘W’ Ribbons Ltd, where ‘the grading structure contained women-only grades which were paid less than any male grade’; the Sealed Motor Construction Ltd, where ‘the majority of women were in lowest grade and paid unskilled male rate’; Anderson Mavor Ltd, where ‘a new pay structure was rejected by the Department of Employment; James Robertson and Sons, where ‘a women-only grade work[ed] 40 hours while the men worked 44½ but the difference in pay was too great to be explained by the extra 4½ hours’; Unbrako Ltd, with its ‘completely segregated grading structure with women occupying the lower grades’; Armitage Ware Ltd, where ‘the lowest grade [was] all female’; and many more. The actions also named the unions AUEW, TGWU, USDAW, EETPU, ASTMS, ACTS, and others as the negotiating parties that had agreed the rates and grades of pay. One finding was against the APEX union, which ‘accepted a new unisex structure’. In almost all cases the parties agreed to make changes before any penalty or finding against them was made.20 In one case a formal investigation was opened at the Luton site of Electrolux Limited.

Legal coercion was an option but it was not always needed, because employers were on the whole eager to keep within the law, and more often sought advice on how to change things than resisted. Once it had found its feet, the Commission found it ‘possible to visit organisations and advise management, employees and trade unions on the legislation and its implications at the place of work’.21 To try to discover the problems, but also as a way of building bridges, the Commission undertook an investigation, with Baroness Seear and the London School of Economics, into the ways that 500 companies (later expanded to 575) had reacted to the new legislation. In those early days the findings were that not much had been done positively, though most complied with the letter of the law.

One reform that the Equal Opportunities Commission championed from early on was the repeal of the special protective legislation that barred women from certain jobs and shifts, such as the Mines and Quarries Act (1954) and the Factories Act (1961). As the EOC News explained, ‘Legislation embodied in the Factories Act dates from Victorian social reforms that were designed to protect women from the “evils of exploitation by unscrupulous employers.”’

But they argued that

today these restrictions on hours of work not only prevent a woman worker applying for the better paid shift work that her male colleagues can do, but they also mean that in many cases, women are not considered for factory jobs at all.

They commissioned research that showed that ‘the majority of working women approved of women being allowed to work evenings and double day shifts’. On the other hand, most women ‘do not approve of it being done by women with young children’. The Commission recommended ‘lifting the restrictions on nightwork, shiftwork and overtime for women and replacing them with legally enforceable Codes of Practice on hours of work, applicable to both sexes’.22

The Commission was supported by the Health and Safety Executive, which had recommended the repeal of Section 20 of the Factories Act 1961 (the section that ‘deals with the cleaning of moving machinery and provides for the protection of women and young persons, but not for men’). The Commission ‘agreed with the HSE’s recommendation that the section should be replaced by regulations ensuring that only trained adults (regardless of sex) should do this work’.23

Convincing industry

The early years of the Equal Opportunities Commission were marked by success. Their newsletter was full of reports and photos of women who were the first in their field, like Linette Simms, the first to drive a school bus for the Inner London Education Authority; Claudine Ecclestone, the first council plumber; Margaret Gardner, the first woman to become a guard on the Underground; Joanne Oxley, David Brown Tractors’ first engineering apprentice; Anne Haywood, training to be Britain’s first gas-fitter; Debbie Ryan, the first to be taken on as an apprentice painter and decorator under the Construction Industry Training Board schemes; and Jacqueline Abberley, training to be Britain’s first train driver.24 There were firsts for women in the professional world, too: Ellen Winser, the first stockbroker; Geraldine Bridgewater, the first woman to be admitted to London Metal Exchange; and Judith Bell, Marine Broker at Lloyds.25

Gwyneth Mitchell, Scotland’s first ever female artificial inseminator, joked to the EOC News that the ‘main qualification for doing the job well was a strong right arm’.

The important innovation in the 1980s was, in parallel with the Commission for Racial Equality, the Equal Opportunity Commission’s work to persuade employers to adopt their own equal opportunity codes, mirroring the legislative framework set out by the Equal Pay and Sex Discrimination Acts in company policy. In a booklet Guidance on Equal Opportunities Policies and Practices in Employment:

[T]he Commission believes that equal opportunities will not be achieved principally by enforcing laws against discriminatory practices; they can only be attained by the acceptance by employers, and employees and their trade unions, that the full utilisation of talents and resources of the whole workforce is important in their own interests and in the economic interest of the country.26

Baroness Seear’s survey, published as Equality between the sexes in industry: how far have we come?, helped the Commission to identify good examples. In all, ‘Eight firms, Sainsbury’s, ICI, Delta Metal, Cadbury’s, Wilkinson Match, Lloyds Bank, H J Heinz and Rolls Royce are singled out for praise in a report’:

ICI, for example, who have a widely publicised policy on equality, have instituted an auditing system with a built-in monitoring function: factory management have a checklist for identifying the cause of imbalances, and suggesting a course for remedial action.

And:

Sainsburys Limited have adopted a particularly positive approach, identifying areas for action, and providing such benefits as a training course for women wishing to return to work, and special training for women to undertake work previously done only by men, for example, in butchery.

In the last case the Commission added that ‘in the last three years this policy has resulted in the doubling of women managers from 41 to 89’.27 Both Rolls Royce and Lloyds Bank had used positive measures to get women into training, in apprenticeships at Rolls Royce, and in a management training scheme at Lloyds Bank.28 Bringing in equal pay had been done through the employers’ federations and the corporate boards that were common at the time:

National Joint Industrial Councils influenced some employers when the Equal Pay Act was introduced, as in the motor vehicle and repair industry. Others were influenced by their appropriate Federations’ recommendations and suggestions. There was an agreement within the chemical and allied industries towards moving towards introducing equal pay four years prior to the effective date of the Equal Pay Act. Central Arbitration Committee Awards were made in respect of at least four employers we contacted.29

Moreover, ‘a few large companies have made approaches to the Commission for guidance in developing policy in the period of the survey, which indicated that willingness to respond to the issues is beginning to emerge’.

The Commission did worry that ‘only a quarter of the companies surveyed by the EOC had written equal opportunities’ policies, and that positive measures they proposed were ‘seen as low priority compared with other business pressures’. Also, they suspected that ‘traditional and attitudinal barriers have been part and parcel of a view that positive action on equal opportunities is unnecessary and costly’.30

Under the Sex Discrimination Act, ‘the Equal Opportunities Commission has the power to make recommendations to the Secretary of State to lay Codes of Practice before Parliament’. Early on, the Commission prepared a draft Code of Practice to be ‘considered by the TUC, the CBI, the Department of Employment and ACAS as well as other interested bodies and individuals’. The draft was published in March 1978.31

In 1985 Baroness Writtle, who had taken over as chair of the Commission, could announce that ‘last April marked a milestone in the history of the Commission in the approval of our Code of Practice by Parliament, with the wholehearted support of both sides of industry’:

The Commission’s Code of Practice on employment came into effect in April 1985, after several years of consultations, and received the forceful and unqualified support of the then Secretary of State for Employment, the Rt. Hon. Tom King, MP.32

As well as providing ‘far-ranging guidance on the promotion of equal opportunities to give effect to the spirit of the law’, the Code now blessed by Parliament meant that it could be used by any employees ‘as evidence in an industrial tribunal’. The Code was launched at a meeting with Tom King MP, Judge West-Russell, President of the Industrial Tribunals, Sir Terence Beckett, Director General of the CBI, Mr Norman Willis, General Secretary of the TUC and ‘over one hundred employers’ representatives from the private and public sector and representatives of the trade unions’.

At the launch the Tory Minister for Employment, Tom King, said:

I believe passionately, that for Britain to succeed, we do have to make most of all the resources that we have: and one of the most neglected resources that we have as a country is the skill, ability and intelligence of many women in society, which has not had the opportunity that it should in the past, but which can make a significant contribution to the future. That is why I support equal opportunities, quite apart from the equity and fairness of it, because for us to succeed as a nation, we must ensure that the potential of women in senior management, professional and skilled occupations is properly recognised and more developed than it has been in the past.

King’s message was echoed by the Confederation of British Industry which issued its own Code of Practice on Equal Opportunities at the same time. The Equal Opportunities Commission’s Code sold 52,000 copies in its first eight months.33

Fifteen years later the Commission would report that in ‘a survey of senior managers in larger UK organisations in Summer 2000, 68 per cent of organisations claimed to have an Equal Pay policy’. What was more, ‘40 per cent claimed that they were currently monitoring the relative pay of women and men’.34 That was a long way off from 1985 though. Looking back, Irene Bruegel and Diane Perrons saw that:

Equal opportunities legislation and in-house equal opportunities policies are generally complementary. The legislation provides a framework for equal opportunities while organisations’ policies set out more practical ways of implementing the policy.35

Beryl Platt was a scientist before she led the EOC

Baroness Writtle claimed that ‘much has changed since the Equal Opportunities Commission came into existence ten years ago, not all of it visible to the public’. Still, she thought that ‘in its totality the change amounts to a record of achievement for which the Commission can fairly claim a substantial share of the credit’. How much was due to the Commission and how much due to broader social changes might be argued over, but in any event Writtle was right to say that ‘the transformation of the attitude of the press and mass media, from one of flippancy and trivialisation to a genuine understanding of the issues, is the most visible change’. The attitude of the general public was one ‘which no longer needs to be convinced’. She highlighted the most lasting change, saying that ‘ten years ago the educational establishment regarded the Sex Discrimination Act as at best marginal to its concerns’. ‘Today’, by contrast, ‘equality of opportunity in education between boys and girls is regarded as a central part of a school’s business’.36

For all that, there was a strong feeling that the early successes of the Equal Pay Act were followed by diminishing returns. So, in the EOC News, it was reported that:

Between 1970 and 1975 when firms were preparing for the implementation of the Equal Pay Act women’s average gross weekly earnings increased from 54.5 per cent of men’s. By 1976 when the Act had come into force they had reached 64.3 per cent. But it looks as if this improvement is tailing off.

The Commission thought that:

It is generally accepted that the Equal Pay Act had a once-for-all effect. There are many other factors contributing to the low pay of women, such as their concentration in low-paid industries, which the Act can have little influence on. The Commission envisages a shift of emphasis over the coming years from ensuring that women are paid equally for equal work to ensuring that the can acquire the skills needed to work in more highly paid occupations…37

Again, in 1982, the Commission had a sombre message, saying that ‘we must also draw attention once again to the fact that the marked progress towards equal pay between 1970 and 1977 has been effectively halted in the last five years.’38 Women’s gross hourly pay seemed to have plateaued at 74% of men’s in the early Eighties.

Outside the Commission, many feminist activists were sceptical. In the magazine Spare Rib Jenny Earle and Julia Phillips wrote that ‘there is little room for doubt that the impact of the Equal Pay Act is dwindling — not that it was ever that substantial’. The narrowing of the pay differential ‘seems to have gone into reverse’.39

Another issue that was hard for the Commission to make headway on was the provision of nurseries. Already, at the Women’s Liberation Conference of 1970, campaigners had connected childcare and women’s equality at work. If women were tied down by commitments to raise children, they would not be able to compete fairly with men in the labour market. The WLM Conference called for ‘free, 24-hour nurseries’. The demand seemed utopian to many, but it crystallised the structural inequality in women’s social position.

The Equal Opportunities Commission took up the argument in 1984, saying that ‘Opportunities for women in employment and other areas continue to be restricted by the inadequate provision of childcare services’. As they argued, ‘services for the under-fives and school-age dependent children are essential in allowing parents to combine careers and public duties with a responsible family life’.40 The harsh recession, along with a government committed to resisting public spending commitments, was not a good time to be asking for greater spending. Ideologically, Conservative Prime Minister Thatcher was sharply opposed to women with young children working, and to nurseries for pre-school age children, which she described as ‘soviet’ in an interview with Radio 4’s Women’s Hour.

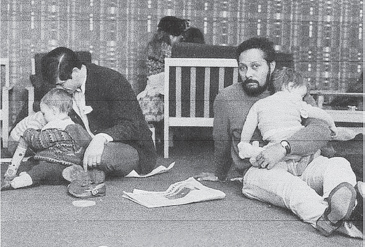

Stuart Hall on duty at the Women’s Liberation Movement Creche, 1970

Later on the Commission would shift its emphasis toward the questions of ‘work-life balance’, flexibility in work, childcare for working mothers, and the minimum wage in its efforts to close the gender pay gap — which we will look at later on. But still, at the turn of the new century the Commission was appealing that ‘the Government needs to reform the Equal Pay Act which is now 30 years old’.41

Betty Lockwood was chair of the Equal Opportunities Commission from 1975 to 1983. Beryl Platt, Baroness Writtle, who had a background in engineering and was a Conservative Party supporter, if a modernising one, served as chair from 1983 to 1988. After Writtle, Joanna Foster was appointed as chair. She had worked in the Conservative Party Press Office in the 1960s, but was also the first chair to have had ‘a background in the women’s movement’.42 Beatrix Campbell explains that the Conservative women put in charge of the EOC played a key role relaying the Commission’s message back to the party: ‘Amongst Conservatives it was left to the Tory leaders of the EOC alone to defend women against their own party and their own government.’43 Foster was replaced in 1993 by Kamlesh Bahl, who had been on the Law Society executive, and working for British Steel and Texaco on equal opportunities issues. Bahl, though, was a divisive figure among the Commission staff, who saw her as a tyrant, preferring the Chief Executive Valerie Amos, with whom Bahl clashed.44 In 1999 Julie Mellor was appointed chair. Mellor had worked in senior Human Resource Management positions for Royal Dutch Shell and the Trustee Savings Bank, as well as for Islington Council, the Greater London Council and the Inner London Education Authority. Jenny Watson, who had worked at Liberty and Charter 88, as well as in some private-sector positions, took over from Mellor in 2005 until the two Commissions, Equal Opportunities and Racial Equality, were combined as the Equality and Human Rights Commission.

As we have seen, the Equal Opportunities Commission’s budget had been kept down to £3.4 million in 1985, rising to nearly £6 million in 1993, when the Commission employed 171 people. Two years before it was wound up, the Equal Opportunities Commission had a budget of £8.5 million and still a staff of 171. The Equal Opportunities Commission was a little smaller than the Commission for Racial Equality, and spent less, but then the CRE also granted a share of its budget to local Community Relations Councils. The EOC, whose head office was in Manchester, supported sub-offices in Cardiff, Glasgow, and Belfast.

Beyond its own offices, of course, the Equal Opportunities Commission was carried by a lively and intellectually productive women’s movement. Women’s groups, though they were often short-lived, proved to be a durable form of not-so-formal political organisation for thousands of women, who argued and wrote and protested in all kinds of ways. College campuses and trade unions also sustained strong women’s groups and caucuses. There were many feminist newsletters and magazines, of which Spare Rib (1972-93) was only the most popular, alongside more short-lived publications like Red Rag and Women’s Voice. Bookshops like Silver Moon (1984-2001), the publishing house Virago (since 1973), and the Fawcett Library sustained many women’s groups. Women’s Studies courses were developed at many universities, though these found it difficult to thrive.45 And as we will see, municipal authorities, especially in the larger cities, were the basis of durable women’s committees and offices. Less declaredly feminist women’s organisations like the Women’s Institute, National Association of Women’s Clubs, and the Mothers’ Union also helped to feed ideas into the Equal Opportunities Commission, as well as promoting the Commission’s work.