The Policy and the Working Class

Equal opportunities legislation was introduced in Britain around the time that the corporatist labour organisation was in crisis. The determination of employers and the government to limit union power — and a marked fall in union membership — in the 1980s coincides with the growth of equal opportunities policies at work.

Unions supported the legislation for equal pay and against discrimination on grounds of sex and colour. As they did so, they also accepted a new framework of legislation on pay that they had resisted. All through the Sixties and Seventies, unions had resisted legal restraints on pay. They defended the right of unions to freely negotiate contracts with employers.

The legislation that they had fought against was designed to limit pay awards by government rules. The laws on pay discrimination were different. They aimed to increase pay. Still, the movement towards government regulation was a novelty.

‘In 1961, the Trades Union Congress, traditionally devoted to voluntary methods of achieving change for its members, called on the Government to ratify the International Labour Organisation (ILO) Convention 100 on equal pay’, noted two researchers at the Department of Employment. They saw that the TUC, ‘in doing this, recognized that as a last resort this might mean that legislation would have to be introduced to enforce equal pay.’1

When the Equal Pay Act of 1970 was tightened up in 1985, the Financial Times’ labour correspondent John Lloyd noted that the Equal Pay (Amendment) Act ‘carries with it further large implications — for the unions’. The laws on sex discrimination, explained Lloyd, offered ‘a large number of workers redress through industrial tribunals (and ultimately the courts)’. Lloyd saw that the question that was troubling many trade unionists was ‘if the law can give workers what they want, will they want us?’ Lloyd looked back at the tradition that the unions had defended of ‘collective laissez faire’ — which is to say that governments did not override the agreements between employers and unions. As Lloyd saw it, two different forces were changing workplace relations: on the one hand there was a growing individualism, and a government withdrawal from the role of negotiator between capital and labour; but on the other hand there was, in the shape of the legislation on equal pay, a growing regulation of labour contracts: ‘British collective bargaining is bit by bit ceasing to be collective laissez faire’, wrote Lloyd.2

Unions had, of course, supported the legislation on race equality and sex discrimination that ushered in firms’ equal opportunities policies. Still there were many points at which unions might clash with the Commissions for Racial Equality and Equal Opportunities. In 1979 the Trades Union Congress spoke out against the Equal Opportunities Commission’s ‘proposals to reduce the levels of protective legislation for women workers’:

The effect of what the EOC proposes is that in many circumstances, employers would have a free hand to decide the hours of employment of women. This is not a step towards the equality of women. It opens the door to their greater exploitation.

Perhaps what provoked the TUC most was the fact that ‘the Commission makes no reference to the work of trade unions in preventing exploitation’.3 For, the Commission Baroness Lockwood explained,

where there is a genuine difference in the points of view of the TUC and the Commission, as there has been in the matter of the reform of protective legislation, I am afraid we shall have to present our own distinctive point of view to the public without fear or favour, and let the public choose.4

Given that the Commission was fending off allegations of interfering in management’s prerogatives at the time, the disagreement with the TUC was not such a problem. The Equal Opportunities Commission often positioned itself as somewhere between the unions on the one hand, and the employers on the other. The Commission’s claim that ‘there is no room for doubt that the momentum towards equality will be lost unless Government and both sides of industry take steps to see that it is maintained’ very much situated it as a ‘tripartite’ institution, which is indeed where its origins lie, though it would become a model of the kind of workplace regulation that displaced the old tripartite system later on.5 In its early days its investigations were often of industry agreements so that the judgments it made were often against both sides of the industry, employer and union, equally.

In the early days of the Commission, Baroness Seear pointed to evidence that:

Shopfloor and local trade union resistance to breaking down segregation is regarded by many employers in printing, chemical process and packaging and pharmaceutical production as a substantial barrier to progress.6

The EOC News reported APEX general secretary Roy Grantham’s complaints that ‘complacency and lack of interest reigned supreme on the Trades Unions General Council’s attitude towards women’: ‘Only 5 per cent of the council’s seats were allocated for the 27 per cent of the movement’s members who were women and they had been “fobbed off for years.”’7

Later the Equal Opportunities Commission would support the activism of women trade unionists, like Patricia Turner, Equal Rights Officer for the General and Municipal Workers Union. Turner wrote in Equal Opportunities News about the growing number of women who were joining unions, contrasted with their less active participation, adding that ‘many men still regard trade unionism as essentially men’s business, to which women are not expected to be committed’. She outlined a number of special measures, including courses and a women’s conference to encourage participation.8 Encouraged by the Equal Opportunities Commission, and knowing that they were recruiting more women than men, the Trades Union Congress published a ten-point charter to press its members to act in 1979. Five years later 40 unions had set up women’s or equality committees, and 25 had appointed equality officers. Some, like the General Municipal and Boiler Makers Union, had provisions for equality officers at branch level.9

Trade unions took up the cause of race equality, too, and the Commission for Racial Equality was more enthusiastic towards them than the Equal Opportunities Commission. In 1980 the Trades Union Congress announced a ‘black equality charter’. The headline point was to ‘get equality of opportunity written into all national and local union agreements with employers’, which was one of the pressures that moved the advance towards equal opportunities from national legislation to the adoption of firm-wide equal opportunities policies. Interestingly, John Monks, for the TUC, highlighted the claim that ‘we are seeking not a legal approach but voluntary self-regulation in the tradition of British trade unionism’.10 The Commission for Racial Equality worked with a number of trade unions, like the NUJ, AUEW, ASTMS, Council of Civil Service Unions, Barclays Group Staff Union, CPSA, and TGWU. The Commission organised fringe meetings at the Trades Union Congress, worked with the TUC’s Race Relations Advisory Committee, and helped to develop the Black Workers Charter that was published in 1987.11 Bill Morris, the Transport and General Workers Union leader, who went on to become TUC president, was a member of the Commission for Racial Equality in the late 1970s.

As part of ‘its training programme for lay persons and lawyers to present cases in industrial tribunals’, the Commission for Racial Equality ‘began training trade union officials’.12 Around the same time, the Equal Opportunities Commission also began training trade union officials to follow cases under the Sex Discrimination and Equal Pay Acts. ‘The majority of applications to Industrial Tribunals’, the Equal Opportunities Commission acknowledged, ‘were from groups of women supported by their unions’. So it was that in 1985, ‘a number of unions including NALGO and APEX asked the Commission to collaborate in the design of training programmes to enable their own officers to identify and pursue test claims’.13

The two Commissions encouraged the equal opportunities cause in trade unions and they helped union officials and representatives to pursue complaints under the laws against employers. As they were doing so they were helping to reform the unions. Beatrix Campbell once called the unions ‘the Men’s movement’, arguing that they had become part of the ‘patriarchal system’. In her view industrial tribunals are to this day ‘congested with equal pay claims, the cause of which is those differentials and bonuses’ that macho trade unionism imposed in the 1970s. Later on, Campbell argues, the unions were reformed by the women’s movement to become altogether more woman-friendly institutions.14 The substantial change was that the unions had reoriented themselves to the new terrain of workplace relations. Instead of collective action, union officials today are more likely to represent their members’ individual claims in tribunals, and with the HR department, often on the basis of the equal opportunities policies that they had negotiated with the management. A more courtroom-style model of union work in committees and tribunals had replaced the earlier parliamentary style of rank-and-file mass meetings. The unions were playing their part in the new regime of equal opportunity workplace organisation.

To drive home the reform of industrial relations that was being put in place, John Major’s Conservative government folded reforms asked for by the Equal Opportunities Commission into legislation that limited trade union power. The Equal Opportunities Commission was glad to note ‘a stated commitment to “equality proofing” of new legislation’.15 The 1993 Trade Union Reform and Employment Rights Act got rid of the ‘length of service’ restrictions on maternity rights, so that ‘every woman who becomes pregnant will be able to take a minimum of 14 weeks’ maternity leave and will be fully protected against losing her job because of her pregnancy’. The Act also included ‘the confirmation of the EOC’s power to draw up a draft Code of Practice on the Equal Pay Act 1970’.

For trade unions, though, the Act had definite downsides. Unions who wanted to take strike action would have to hold a postal ballot (bringing an end to the mass meeting vote on industrial action) and also to give advance notice to employers of any such action. The Act was, according to Labour peer Bill Wedderburn, the end of a campaign whereby unions were ‘regulated, harried, battered, fined and sequestrated, step by step by step, in Act after Act in pursuit of the aim of decollectivising the workplace’. ‘Is not the world of tripartism’, summarised Lord Skidelsky approvingly, ‘completely out of date’.16 Some reforms directly linked advances in equal opportunities with dismantling the older model of collective bargaining, such as ‘the right for individuals affected by discriminatory rule in collective agreements to ask an industrial tribunal to declare the rule null and void’.17 The Equal Opportunities Commission of course supported the Act, Baroness Writtle speaking in its favour, and its main provisions welcomed in the Annual Report as a positive step forward for women, as it was at the same time a reform of industrial relations. Under this new regime, workplace relations were both more individuated, and also more regulated.

More recently the rules governing Employment Tribunals have changed to prioritise claims under discrimination legislation. As it stands, an employee can bring a case against his or her employer if they have been working there for two years. That threshold is lower if the claim is made on the grounds of sex or race discrimination (as well as a few other exceptions). More, an employee who is making a claim for unfair dismissal can be compensated, but only up to the sum of £76,574, or one year’s full pay, whichever is lower. There is no such limit on cases that are brought under the laws on sex or race discrimination. Understandably, employees and their representatives, often trade union officers, have worked out that they have more rights to pursue cases that can be understood as race or sex discrimination. A great many grievances people have against their employers do have some element of sex or race discrimination, and complainants are more likely to frame their complaints in that way if they can. The consequence is that in 2014 fully 55% of all cases were brought under sex discrimination law, a marked rise since just 2012, when the percentage was 38.18

Though the Equal Opportunities Commission took to working with the trade unions, they were still ready to investigate cases where unions might be discriminating. In 1986 the Commission reported Diana Robbins’ investigation into widespread discrimination against women in British Rail, and the railway unions’ collaboration in it. Local managers who were in charge of recruitment, found Robbins, ‘were largely hostile to employing women’, and a wide range of ‘indirectly discriminatory recruitment criteria and processes were used including age bars, mobility requirements and word-of-mouth recruitment’. Damningly, Robbins ‘found the railway unions uninterested in equal opportunities’.19

SOGAT ’82

The most pointed investigation of a union that the Equal Opportunities Commission undertook, however, was that of SOGAT ’82, the printers’ union, between 1984 and 1986. The case against the Society of Graphical and Allied Trades was pretty clear cut. As the descendant of the centuries-old printers’ guilds, print unions had much more say over work than most unions do. For many years they had controlled access to their trade and jealously guarded the skilled craft against the introduction of new technologies that might undermine their power. Work was allocated through the union branch. The print unions had been and still were organised around a male monopoly over work, ‘the historical demarcation between “men’s work” and “women’s work”’. In SOGAT ’82 that was clear in the division between ‘the London Central Branch (the LCB) and the London Women’s Branch (the LWB; this branch later became known as the Greater London Branch)’: ‘The Commission found that… specific practices resulted in LWB members either remaining ignorant of or being denied access to the higher paid and higher status vacancies controlled by the LCB.’ One instance flagged up was that of

threats made by an LCB Chapel to take industrial action if a woman were employed as a binder at a craft bindery [which] amounted to an attempt to induce the management of that firm to discriminate against the woman contrary to… the Act.

The Equal Opportunities Commission’s investigation of SOGAT coincided with the publication of Cynthia Cockburn’s book Brothers: Male Dominance and Technological Change in 1983. Brothers is a brilliantly researched account of the print industry in Britain which highlights the way that the jealous defence of craft skills served to secure men’s domination of the industry. Cockburn’s account also echoes some of the employers’ criticisms of the printers’ ‘phenomenal earnings’, that the compositors’ ‘wage levels were indeed staggeringly high’, and that the linotype operators were ‘virtually writing their own pay cheque’.20

When the Commission first talked to them in 1984, ‘SOGAT and the Branches were unwilling to put an end to this serious and continuing discrimination’. The union ‘maintained that their practices were justifiable and that alterations to these arrangements were both impracticable and incompatible with the Union’s democratic organisation’. At that time the Equal Opportunities Commission ‘decided therefore that it would have to enforce the necessary changes, and in June 1984 the Commission informed SOGAT and the Branches, in accordance to the Act, that it was minded to serve on them non-discrimination notices requiring to change their call room and seniority practices’. At this ‘the two Branches asked the Commission to defer the final decision on the issue of the non-discrimination notices, so as to give them time to amalgamate’, and a ballot was held which ‘returned majorities in favour of amalgamating the LCB with the LWB’. Welcoming that decision, the Commission heard that ‘owing to a series of internal and external difficulties the Branches were unable to complete the amalgamation’. For that reason, the Commission served its notice of discrimination at the end of 1984.21

They reviewed the case in 1986 and found that ‘the parties continued to experience difficulties’. When they met with SOGAT that year, they thought ‘it was apparent that the impetus for change had been lost’: ‘In September the Commission accordingly issued non-discrimination notices in a form almost unchanged from those prepared in 1984.’22

What the Equal Opportunities Commission did not explain in its reports was that the external difficulty that the union was experiencing was a dispute over the introduction of new technologies that would lead to the destruction of their trade and the end of their union. News International, which owned the Times and the Sun newspapers, moved the whole operation from Fleet Street to Wapping, sacking 6000 print and clerical staff, and introducing a new computer graphics system called ATEX. Already, Times Newspapers Limited, under its previous management, had faced down a year-long strike in 1978-79 over manning levels, at the end of which the new technology had been brought in, but still operated by the printers. As Cockburn wrote in 1983 just before the change, ‘often a new labour process implies a new labour force’, as ‘a company sacks one lot of workers and engages others’. But in the aftermath of the 1978-79 strike the employers’ side was ‘forced to convert its existing craftsmen’, which was, Cockburn thought, ‘an unusual situation’.23

The Wapping dispute

In 1984 the General Secretary of the SOGAT union was Brenda Dean, who had just taken over from Bill Keys. Before going ahead with his move Murdoch had secretly negotiated with Dean who offered a reduction of manning levels at News International. What Murdoch wanted to know from Dean ‘was whether I could assert my new authority over the London members of SOGAT’. In her memoirs, Dean felt she had to explain how it was that she had secretly met with Murdoch and his chief executive Bruce Matthews. People would be surprised, she thought, to know how many such meetings ‘have littered industrial history and to find that quite often, when harsh words are being hurled across the headlines, remarkable trust and complete confidentiality can co-exist between the two sides’.

Explaining her willingness to push Murdoch’s line, Dean explained that ‘I was looking at the wider picture and wondering how I could break the logjam of the Fleet Street workers’ attitude’, adding that ‘change, like it or not, was coming fast’. Murdoch was impressed by Dean but had his doubts about her ability to deliver the traditionally militant print workers: ‘I looked him straight in the eye and told him I did not know but I was going to have a bloody good shot at it.’24 But while he was talking to Dean, Murdoch had secretly arranged a ‘sweetheart’ deal with the electricians’ union, the EETPU, and its leader Eric Hammond, to replace the print workers with their recruits.

Gender was key in both Brenda Dean’s relation to the London print workers and also to the Wapping dispute. When Dean won the vote for General Secretary she became the first woman to lead a trade union. Dean saw union militancy as intrinsically male, writing about the ‘left-wing macho clique’ that opposed her. Her base of support was outside London, where more women worked in the trade. She was facing down the ‘London Central branch who ran the union and where the power lay’, trying to rein in the ‘bloody-mindedness and strong-arm tactics for which the London print workers were infamous’, as she saw it. When the conflict with Murdoch came, ‘the testosterone amongst London print workers, who loved a fight, convinced them that they would win it’. In Dean’s mind, if only the London Central Branch had been faced down earlier, the union ‘might have avoided the ultimate disaster of Wapping’.25 Dean’s charge of testosterone-fuelled, macho militants echoed the allegations of ‘picket line bullies’ that could be heard from the Tory backbenches and in the tabloid press. Feminist Beatrix Campbell wrote of the characterisations of trade union ‘Barons’ and ‘bully boys’, that ‘trade unionism is constantly represented in Tory women’s discourse as the unacceptable face of masculinity’.26

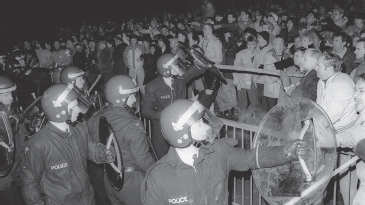

The dispute was very bitter, and the sacked workers protested outside the Wapping print works for a year. Though you might not have known it from the press reports, hundreds of women, mostly clerical workers, were also laid off and took part in the campaign, as did many of the male print workers’ wives. The violence was intense, with mounted police baton charges made in narrow streets against strikers and protestors, and one 17-year-old protestor, Mike Delaney, was run over and killed by a News International lorry. The strikers fought hard too.

It was generally a miserable time in Britain in the winter of 1986, when one of the most popular television shows was the darts, where a top score would be greeted with the chant ‘ONE HUN-dred and EIGHT-ee’. On one of the many protests held outside the Wapping plant, I saw protestors pull up iron railings to throw at the police. A rail sailed over my head like a javelin and hit a policeman’s shield, sending him sprawling on the floor. Behind me were a row of women in fur coats who, like a Greek chorus, called out, ‘ONE HUN-dred and EIGHT-ee’.

One protestor, Deirdre, told John Lang and Graham Dodkins that she had often attacked the trucks: ‘peaceful demos were hopeless. It sounds terrible, but I really think we should have done more damage. I think it was war, I really think it was.’ Another, Joyce, took issue with the tenor of the SOGAT leadership’s campaign:

There was a Women’s march at Christmas time… [A] girl at the front next to Brenda started singing ‘Little Donkey’ through the loud hailer. I couldn’t believe it, I thought, ‘this is a farce’… [T]hat was the idea, that it should project the usual symbol of women as the Earth Mother. But I said, ‘what is this, peace and love and make the sandwiches, is this what we are reduced to after all these months? Peace and love and light me a candle sister: Come on.’ But I can see that Brenda would think it was a good image: women the peace-makers instead of big, macho pickets beating up the Old Bill and chucking smoke bombs.27

Writing in Spare Rib, another striker Liz Jones saw the struggle as:

[A] war where the people who were called out to fight for their union, find their union reluctant to fight for them, and stand accused of being ‘wreckers’ when they tiresomely persist in fighting on for reinstatement and union recognition long after their leaders have decided the fight is unwinnable. 28

Eventually Dean announced that despite successive votes against, the union would abandon the print workers, to save the union office: ‘This has been a very difficult decision for the executive to take’, she said, ‘but what they were faced with was the sequestration of our total union and a fine’.29 In any event the union did not survive. Once the print workers at New International had been defeated, all the other newspapers adopted the new technology and the jobs of compositors and other metal-type print workers came to an end. With the union wound up in 1992, the difference between the London Central and Greater London Branches of SOGAT was no longer an issue.

Racism at Ford

Even more than the Equal Opportunities Commission’s intervention in SOGAT, the Commission for Racial Equality’s at Ford UK Limited had a lasting impact on the firm. Ford UK’s website today boasts: ‘Ford is a leader in the practices of diversity and inclusion and established a formal equal opportunities policy more than 30 years ago.’ In 1978 Ford UK’s Industrial Relations manager Bob Ramsay became a member of the Commission for Racial Equality, beginning decades of collaboration between the company and the Commission. ‘We believe that a key ingredient to business success is the diversity of our workforce where differences are valued and everyone is included’, Ford UK says today.30 The company has also supported a wide range of community activity with large donations, from sponsoring 80 young black students at the Eastside Young Leaders Academy, to contributing to Gay Pride. Ford UK have worked closely with the former Commission for Racial Equality chair, Herman Ouseley, and are active sponsors of his Kick Racism Out of Football campaign.

In 2011, for the sixth year running, Ford hosted the Kick Racism Out of Football campaign event in East London. Mitra Janes, Diversity and Inclusion manager for Ford of Britain, said: ‘We are delighted to continue our support for Kick It Out. Football is diverse and inclusive and is a great platform for our involvement.’

Lord Herman Ouseley, Kick It Out chairman, said:

Ford has once again put on a fantastically engaging event. We are very proud to be working with Ford, and partners in the Dagenham area, on an initiative that will have a lasting impact on young people. Ford is to be congratulated for an enlightened approach to issues that impact on its local communities.31

As we have seen, Ford has often been accused of discrimination, and used a racial hierarchy between overseers, skilled, and unskilled workers into the 1980s. In the mid-Eighties Ford workers at the Dagenham car plant walked out after two supervisors were seen handing out racist leaflets, shutting down the production line (one of the supervisors, Tony Lecomber, had long been active on the far right). Afterwards the company worked closely with the Commission for Racial Equality, and with the unions, to try to repair its reputation and its equal opportunities policy.

In November 1985 Dagenham management wrote to workers to say ‘how seriously the Company takes its commitment to Equal Opportunities’. With the Joint Workers Committee, managers set up the Joint Equal Opportunities Committee. At that time 38% of Dagenham’s 12,000 workers were black, though they were mostly in the lower grades.32

The Paint, Trim, and Assembly plant at Dagenham

Despite the paper commitments, race troubles kept on coming up. In 1988 union stewards took up the case of a black applicant for the truck fleet at Dagenham, who was turned down because informally the drivers were all white.33 Nine years later Ford payed out over £70,000 to eight Asians who had been refused work on the truck fleet.

The background to the rising tensions was Ford’s continuing push to dismantle the strong shop steward movement, and rank-and-file activism at its Dagenham and other plants. The company brought in new arrangements where people worked in teams under a leader. What management called ‘flexibility’ meant mostly working much faster. Managers put a mean pay offer in 1987 of just 5% over three years, but they misjudged the mood and the workforce voted overwhelmingly to strike in 1988. The deal that the union eventually agreed, though, was not much better in pay, and was still to be phased in over two years. More importantly the agreement demanded more ‘flexibility’ from the workforce. In all of these agreements the company went over the heads of its more militant shop stewards to deal with the union head office.34

At the same time as management were side-lining the local union, they were putting in place the system of group leaders ‘to encourage production workers to share management’s viewpoint’, as one worker commented, and also to cut staff by laying off more than half of the supervisors. A ‘Memorandum of Understanding’ in September 1988 set out a more ‘constructive way of doing business together’ and set down that ‘the Trade Unions have affirmed their commitment that employees will not be involved in unconstitutional action’. Two years later Ford brought in its Employee Development and Assistance Programme, its own kind of Human Resource Management package, that drew individuals into tailored training and assessment. Ford manager John Houghton said that ‘EDAP was seen as an enormous catalyst in changing Industrial Relations in Ford because it was nonconfrontational’. EDAP, of course, was an extension of the equal opportunities agreement, with managers taking control of relations with employees on an individual basis, with the collective action of the union playing less of a role.35

Despite the EDAP and the equal opportunities policy, racial persecution of workers by managers kept reoccurring. As well as the embarrassment of the ‘whites only’ Truck Fleet, Ford shot themselves in the foot when a publicity shoot of the workforce was weirdly doctored around 1995. Those that had modelled the part of themselves in this evocation of a multicultural workforce were astonished when they saw a version of the shot where all the black workers had been photo-shopped into white people. What few saw at the time was that the shot was doctored for publicity for a recruitment drive in Poland, where the black population is negligible. It was a crass decision by a designer who had not thought through what would happen when the Dagenham models saw themselves whited out. The episode seemed to show up the insincerity of the equality drive to many cynical workers. A walk-out was narrowly avoided and Ford compensated the insulted participants.36

The Dagenham workers’ distrust of the equal opportunities policy seemed to be confirmed in the hazing of Engine plant worker Sukhjit Parmar. Parmar recalled that the bullying went on for four years, led by the ‘foremen and the Group leaders’. He was dragged across the shop floor by a man shouting ‘You Paki bastard’; his food was kicked out of his hand into his face; and on one occasion he was sent into an oil mistifier unit, without the needed face protection, and locked in while people were laughing. ‘The company were aware of what was going on and they did absolutely nothing to prevent it’, said union representative Steve Turner. When Engine plant foreman Joe Hawthorn and group leader Mick Lambert were disciplined, they rallied white workers in the Engine plant to refuse to work with Asians. Around the same time Shinder Nagra took action against Ford after similar attacks. Long-time union activist Berlyne Hamilton argued that discrimination and racial bullying ‘has been going on for years’; ‘It is enshrined in the system.’ More than 1000 workers at the Paint, Trim, and Assembly Plant walked out, protesting against racist bullying.37

Around the time of the Parmar scandal, Ford’s global CEO, Lebanese-born Jacques Nasser, visited England. By one account he ‘was absolutely livid when his company was accused of being racist’. His conclusion, though, was chilling for the Ford workers, white and black: ‘I’ve had enough of Britain’, he said, ‘I’ve had enough of this plant — all I hear about is problems’. From the point of view of the global CEO of Ford that might have made sense. But from the point of view of the employees it seemed as if they were to be blamed — and punished — for the race discrimination that was coming from their line managers.38

In March 2000, ‘nominated CRE commissioners heard oral representations from a Ford delegation… to help them decide whether to embark on a formal investigation’. Later that summer the Commission for Racial Equality suspended the investigation ‘following assurances by Ford senior management that the company would comply with stringent conditions for improvement’, and ‘representatives met regularly with Ford throughout 2001 to review progress’ under a Diversity Equality Assessment Review (DEAR).39

A special ‘Equal Opportunities Meeting’ between union and management representatives heard plant manager Jeff Body say that as far as racism went, ‘the company needed to take on the Trade Union’s issues and respond’, but that ‘the culture change needed to be within the Modern Operating Agreement’. Body led the unions to believe that Nasser had said that he could fix the problem by closing the plant if they did not agree. In disbelief, union representative Steve Riley had to ask whether ‘Nasser was saying that the plant was under threat due to Equal Opportunities issues’. Car production at the Ford Dagenham plant was stopped in 2002. Though 5000 were still working on diesel engine production, the rebellious Paint, Trim, and Assembly plant was closed. In 2013 the remaining jobs (related to production at Southampton) were lost and the plant closed.40

Sheila Cohen interviewed activists in the Transport and General Workers Union branch for the Paint, Trim, and Assembly plant at Dagenham. One, Roger Dillon, won a discrimination case against Ford for the effective racial segregation of the plant (between its north and south estates). He was largely unimpressed by the Commission for Racial Equality, though: ‘the CRE was in bed with the Ford Motor Company — they were wined and dined’. Dillon went on to say that ‘the company spent millions on Equal Opportunities — but they never changed… they were just ticking the box… The policy documents are used as a cover.’ In 2003 Ford UK Ltd ‘came fourth in Race for Opportunity’s (RfO’s) diversity benchmarking survey of private companies’ — the year after it closed car production at Dagenham.41

In the case of the SOGAT ’82 investigation and the equal opportunities policy at Ford Dagenham, paper equal opportunities policies were doing nothing for industrial workers under attack. If anything, the new way of talking about workplace relations cast these employers as out-of-date dinosaurs, who would have to make way for change. It was not that the policies were responsible for the changes that were taking place. But they did add to a perception by managers, and by union leaders, that collective action and workplace militancy was outdated, or ‘macho’. The top-down equal opportunities policies were a part of the way that management, government, and union leaders were reordering life at work, which was at once more individuated, but also more regulated.

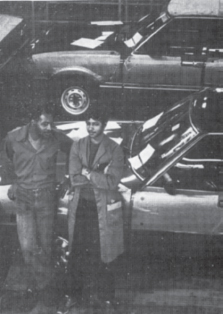

The British economy often seems to go through a cycle of strong growth, followed by a recession or even a crash, slowly recovering again. The metaphor of the economic cycle, though, covers up a marked change in the way that labour was and is rewarded. When organised labour was strong workers got back around 58% of what they made, giving up the rest to the employers’ profits. From 1983 workers’ share of output fell back to under half, while the employers’ share rose accordingly. The cycle had a big impact on employment and the make-up of the workforce, but the reforms of the 1980s decisively shifted the share of income in favour of capital. One way that re-division of the spoils was hidden from view was that overall output grew, so that while workers’ share was less, the absolute amount they got was more.

In the long trend, Britain’s economic output grew from £874 billion to £1.8 trillion between 1971 and 2014. That growth was punctuated by recessions in 1974-75, 1980-82, 1991, and 2009. Recessions often led to people being put out of work — though the long trend is for a growth in employment from 25 to 30 million.

After the spring of 1975, 150,000 jobs were lost from a total just short of 25 million, and not recovered until 1979. This recovery was brief, and between 1980 and 1983 the numbers in work fell from 25,225,000 to 23,630,000 — a loss of 1.5 million jobs. Not until 1987 did employment return to the 1980 level.

Source: ONS

As we have seen, it was feared that recessions would hurt the advances that women had enjoyed in periods of economic growth.

The impact of the recessions on the numbers of men and women in work were different. Male employment fell from 1973 to 1978 by half a million to 15.16 million. Over the same period women’s employment grew by half a million to 9.6 million.

Between 1980 and 1983 women’s employment fell from 10 million by 300,000. In July 1980 the Equal Opportunities Commission warned a House of Lords Committee that unemployment was rising faster for women than men. A more likely explanation was ‘the increased tendency of women to register as unemployed as compared with previous years’. Men’s employment started to fall the year before, in 1979, and 1.3 million jobs were lost to men up to the spring of 1983, when the numbers in work fell below 14 million. Not until 1989 did male employment return to its 1979 peak, whereas women’s jobs were back at 10 million in 1984 and continued to climb to more than 11.75 million in 1990.42 The Equal Opportunities Commission highlighted the demand for labour to make the case for more nursery provision, writing that ‘the dip in the number of school leavers combined with the growing skill shortages requires a major national effort to get the work family balance right and make it easier for working parents to be effective at work and at home’.43

Between 1991 and 1994 overall employment fell again, from 26,871,000 to 25,303,000, more than 1.5 million jobs lost. Not until 1997 were those jobs recovered, and the numbers in work carried on climbing until 2009. In 2009 half a million jobs were lost, though these were recovered in three years. In the recession of 1991 around 300,000 women employees’ jobs were lost while more than a million men’s jobs were lost. In 2012 men made up 53% of all those in work — around two thirds of all women of working age work, while three quarters of all men of working age work. One important qualification is that many more women work part-time — about three sevenths of the total, while only one eighth of men work part-time.

It is worth trying to unpick what has happened. The metaphor of the ‘economic cycle’ is not as good as it seems.44 The idea of the cycle is that things go up and down and that we get back to the point that we were in before. The metaphor of the cycle is a way of reconciling change with the prejudice that things do not change.

The theory of the economic cycle, as far as the employment of women and ethnic minorities goes, suggested that they would be a ‘reserve army of labour’ — put to work in flush times, and then laid off again when times were leaner. Marian Ramelson first suggested that this might not quite be what was happening with women in the labour market, when she anticipated that ‘even if the economy goes into a slump or crisis the evidence is that the relative role of women at work does not decline’.45 What was more, the way that the employers and the government had dealt with organised labour in the 1980s had changed the way that the labour market worked. It was true that there had been a contraction in employment in 1980 and another followed in 1990. But overall the tendency was towards an expansion of the numbers in work. From 1995 onwards the numbers in work grew, not just in Britain, but across the developed world, at a higher rate than the population. The International Monetary Fund called it ‘job-rich growth’, noting that it was a reversal of the preceding period of capital-intensive growth that followed the Second World War, and ran up to the late Seventies. Most recently, the recovery from the 2008 recession saw a sharper increase in both full-time and part-time employment for women, and an increase in part-time jobs for men, but almost no new full-time work for men, according to the Resolution Foundation’s 2015 survey.

A surprising feature of the ‘job-rich growth’ from the mid-Nineties was that it did not provoke wage inflation, as the economists expected. The reason was that something had changed in the labour market. The organisational and ideological defeats suffered by the labour movement meant that even when the recovery came, they were in no position to take advantage of it. Employment gains, concluded the EC’s Directorate-General for Economic and Financial Affairs, reflect ‘the effects of several years of wage moderation’.46 With wages constrained, it was cheaper for employers to expand their businesses by taking on new workers, than by investing in new machinery. The United States and Holland expanded their workforces by inward migration; Germany, by assimilating East Germany into its modern economy; Britain did allow more migrants to come in the 2000s, but largely expanded its workforce by putting more women to work.

The process of recruiting women into the workplace was not planned exactly. Indeed, many senior government figures were saying that the opposite should be happening. The Equal Opportunities Commission said it was ‘suggested in an increasing number of places that one solution to the problem of unemployment is for women to return to the traditional role in the kitchen’.47 But that was not what happened. The change in the gender make-up of the workforce went the other way, as the economy was restructured. Older industries were downsized or broken up. More jobs were created in the service sector. The older jobs were often in unionised firms, the newer jobs more often not; the older jobs were more highly paid, the newer jobs were often not; the older jobs were full-time; many of the newer jobs were part-time, or had irregular hours; the older jobs were permanent, but more of the newer were on temporary contracts. More of the newer jobs went to women, less to men. Men who were used to higher wages and better conditions had to think twice about taking these service-sector jobs on, while they might be a step up for women used to earning less; older men were often demoralised by the collapse of traditional industries. The President of the Society for Population Studies, David Endersley, thought that ‘in traditional areas like the North East unemployment has forced changes in family work patterns and whereas men are losing jobs by their thousands, women are finding more work’. ‘There’s a very sharp increase in the number of households where the women’s earnings are predominant and the larger part of the household income,’ he added.48 Where there was a deliberate choice to employ more women, and also ethnic minorities, was in the adoption of equal opportunities policies by employers.

The position of women relative to men improved, but men still had more jobs than women. It does not follow that women’s position improved absolutely. It changed. Some things were better. Some were less so. One decisively positive change was that many more women at least had the chance of economic independence. Nearly half of all driving licenses issued are to women, and nearly 4 million women live alone. Economic dependence on men put many women in a vulnerable position in the 1960s, whereas today the possibilities of leaving a difficult relationship are a great deal easier, and since 1991 rates of domestic violence have fallen markedly.

Whether we think women were better off over all depends on what you think of employment – certainly they were working more. Looking at what had happened to men and women in relation to their employers, the picture is different.

Schematically you might say that in 1970 15 million men and 9 million women made goods and services to the value of £830 billion (in 2016 pounds). So perhaps 6 million women worked full-time raising children and keeping home, while another 3 million did that for part of the time, while working for the other part.

By 2015 16.5 million men and 14.5 million women made goods to the value of £1.8 trillion. Six million of the women were working part-time, so were most likely raising children or keeping house in the rest of the time. Two million of the men were also working part-time. Perhaps another 2 million women were raising children full-time.

The workforce increased by 5 million, which means 5 million more pay packets — an increase mostly down to the increase in women working, and largely possible because of a fall in the time spent on housework (which we consider in the next chapter). Double-income households were better off in cash, but time-poor.

If we look at the share of the billions of pounds of output that fell to the workforce as pay we see that as we have moved in the direction of gender equality at work, employers did better relative to employees (see graph above). Between 1948 and 1979 employees’ compensation — wages — made up 58%, on average; from 1983 to now, workers’ share of output dropped to 49%. Women improved their position relative to men, but employers did best of all. They spent £888 billion setting 30 million people to work to make goods to the value of £1.8 trillion, earning £930 billion for themselves. In 1961 they spent (the equivalent of) £342 billion to put 25 million people to work, to make goods to the value of £583 billion earning just £241 billion for themselves. Those 5 million new workers were making a fortune for British business.

Equal opportunities policies had costs. It would cost to pay equal wages. Beatrix Campbell estimated that ‘if women in the banking system in Britain were paid the same wage as men for work of equal value the banks would have to find an estimated £17 billion to cover the cost’.49 As it happened the costs were not so great since the women were often taken on at lower grades and less pay, while at the same time the men’s wages were being held down. The horizon of equal pay approaches not just on the basis of raising women’s wages, but also on the basis of holding down men’s.

The idea of the ‘family wage’, according to many of the feminist critics of the old order, was archaic — and they were right. The idea that men were breadwinners and women’s earnings were just ‘pin-money’ reinforced the authority of husbands over wives. Unfortunately, the end of the family wage was really just a limit on wages that meant that both partners had to work just to earn enough to live on, and women’s hours were annexed to the office, shop, or factory, putting great strain on families that became work-rich and time-poor.50

Manchester council workers demonstrate against the threat to deport George Roucou, 1987

Government also spent more on nursery places. But overall the business case for equal opportunities looks pretty solid.

The relation of black workers to the economic cycle was different. As we have seen, the two largest non-white minorities in the UK in the 1970s, Afro-Caribbeans and Asians, were both hit disproportionately hard by the recessions of the 1970s and the early ’80s. Overrepresented in industry, black and Asian workers suffered as industry was downsized. They were hurt, too, by their concentration/ segregation into certain kinds of factory work (like textiles in West Yorkshire or the furniture trade in Tottenham) that were declining. Official oversight on the part of police and immigration services made black workers less secure and opened them to discrimination by employers and workmates alike. The demand that black workers show their passports to employers fixed the idea that they were second-class workers as they were second-class citizens. Most importantly of all immigration from the black commonwealth was slowed by the 1981 Immigration Act and the many subsequent acts to ‘close loopholes’. The impact on work and pay was clear: ‘The ethnic wage gap increased from 7.3 in the 1970s to 12 per cent in the 1980s, whilst the unemployment differential increased from 2.6 percentage points to 10.9 percentage points.’51

In the 1980s, the non-white share of the population of Britain rose more slowly, through secondary migration (wives and families joining men who had moved in the Seventies and Sixties), or through natural growth. The recession at the start of the 1990s did not see much of a difference in the ethnic pay gap. Black earnings were 11% lower than whites’, while unemployment was 9.8% higher.52 There were some differences emerging though. Indians were doing better relative to Afro-Caribbeans and Pakistanis.

From the mid-1990s a second wave of migration came to Britain. Political conflict and dislocation in a number of developing countries led to a resurgence of movement to Britain by asylum-seekers. Between 2000 and 2010 around 7000 Somalis were granted British citizenship every year, and the 2011 census identified 101,370 Somali-born residents in England and Wales. Other African migrants came as asylum seekers from Algeria in the early ’00s, from the Congo and from Zimbabwe (in 2003 the production line at Cowley, where a mostly white workforce had been employed 20 years earlier, had a team of Zimbabweans assembling cars for BMW, under a Mozambican supervisor). There were 201,184 Nigerian-born and 95,666 Ghanaian-born people living in in Britain in 2011. One important shift is that there are now more ethnic Africans than Afro-Caribbeans in Britain. Another important source of inward migration was from Poland, the Polish population of Britain doubling to reach 1.1 million between 2001 and 2011.

The way migrant labour was curbed and then encouraged has led many to see race as tied closely to the economic cycle. Some have argued a direct relation between the economic cycle and the liberality or otherwise of the immigration law. On this view when the economy is expanding the tap is opened to recruit more migrants to work in British industry — as it was in 1948 when the economy was expanding post-war. Later, when growth faltered and employment prospects were poor, immigration was restricted.

This view of immigration law as a response to labour needs seems compelling. But a closer reading of the record of legislators’ decision-making shows that far more ideological concerns about national identity, the loyalty of indigenous white populations, and fears over international standing all played a part — and in particular the raft of anti-immigrant measures passed in the 1980s were without much practical rationale, but rather expressions of a fear of loss of national identity, and an assertion of control on the part of the elite.53

Towards the end of the 1980s the punitive attitude of the authorities towards black people was mitigated by a growing official recognition of discrimination. Where Lord Scarman’s report into the Brixton riots in 1981 fell on stony ground, the police started monitoring racially motivated attacks around 1989, and these were criminalised in 1998, shortly before Sir William Macpherson’s report into the killing of Stephen Lawrence put ‘institutional discrimination’ into the public eye.54 The official outlook on race was changing, holding up a good ideal of the loyal black Briton, contrasted with the illegal migrant. A Conservative election poster in 1983 had a picture of a smartly-dressed Afro-Caribbean man, with the slogan, ‘Labour says he’s black. Tories say he’s British.’ The adoption of equal opportunities policies is a part of that transition in attitudes to race. Settled and accepted ethnic communities have seen their positions improved. Those who are more recent arrivals, or are Muslim, have done less well. So Indians’ earnings are not less than those of their white counterparts, and Afro-Caribbeans’ only very slightly, whereas Bangladeshis, Pakistanis, and Africans earn around four fifths of the white earnings.

One way of looking at the working class has been the model of the ‘segmented labour market’. Charles Leadbeater saw a workforce ‘radically divided’ between a core of permanent workers, skilled at its centre, along with unskilled; around them he saw a peripheral workforce that is in temporary or part-time work; then there are the recently unemployed, and then a layer of long-term unemployed. It was ‘a strategy to legitimise a society where roughly two thirds have done, and will continue to do, quite well while the other third languish in unemployment or perpetual insecurity’.55 Luc Boltanski and Eve Chiapello highlight these changes as part of the ‘New Spirit of Capitalism’:

Casualization has led to a segmentation of the wage-earning class and a fragmentation of the labour market, with the formation of a dual market: on one side, a stable, qualified workforce, enjoying a relatively high wage level and invariably unionised in large firms; on the other, an unstable, minimally qualified, underpaid and weakly protected labour force in small firms, dispensing subsidiary services.56

The segmented labour market is clearly an important way to understand inequality between sexes and races. Gill Kirton and Anne-Marie Greene look at the idea of dual labour markets where jobs in the primary sector are better paid, full-time, with better promotion prospects and more job security: ‘the primary labour market holds mainly “male” and “white” jobs, and the secondary sector “female”, “older worker” and “ethnic” jobs’.57 This is a similar model to that of the ‘reserve army of labour’, only fuller perhaps. As Kirton and Greene state, the model is not perfect, and does not explain the advance of women’s status at work. The model has explanatory power, but its weakness is that it tends to fix in time a snapshot of what is in fact a changing social and economic landscape. So, for example, many skilled industrial workers of the 1970s, like car or print workers, who would have certainly been reckoned among the core workforce, quickly discovered that they were no longer needed and were pushed out into the ranks of the unemployed. Moreover, the ideal of the ‘job for life’ was rarely met: some at the Cowley car plant in Oxford were laid off and then taken on again six or seven times, as the market rose and fell, and the plant changed hands from Pressed Steel, to Morris Motors, and then British Leyland. For our purposes here, the problem with the market segmentation model is that it tends to minimise the real changes that have taken place, and reinforce the idea that things are pretty much as they have always been.

In the early ’00s British Airways began to lose customers, stalling a planned expansion. The company employed 57,000 people, four fifths in the UK. Needing to find cost cuts of £650 million over two years, BA planned to cut 13,000 jobs. Another company, at another time, might well have used the principle ‘last in, first out’, meaning that those with the shorter length of service would go first. Such informal agreements often discriminate against black people, and against women, as they tend to have shorter job tenure. British Airways had a workforce that was ‘very diverse, with a high proportion of women and different cultures, religions, races, ages and abilities’ — though that was less true of its management.58

British Airways was self-conscious about the need to avoid what they called a ‘knee-jerk’ response to cost-cutting that would cause problems. They were also very committed to equal opportunities and ‘diversity management’, and had been for many years. Not only did BA avoid the ‘last in, first out’ approach, but they also were wary of trying to meet the problem through voluntary redundancies, fearing that this would jeopardise the work that they had put into recruiting a diverse workforce. They were conscious, too, that it is easier to address equal opportunities ‘in the context of a company that is growing’, but that ‘downsizing makes it more difficult to make progress on the representation issues’. According to one manager: ‘we wanted to check we had not got rid of disproportionately more women, or more disabled, or people with different ethnic backgrounds’. Overall, the job losses were borne equitably between men and women, and between black and white — 17,395 women were laid off, and 24,102 men; or, looked at in terms of race, 31,798 white people, and 4,679 black and Asian people lost their jobs.59

British Airways’ progressive approach to diversity did not save the 37,000 jobs, but it did make sure that the losses were evenly shared. Managers took pride in their approach. But it was little comfort to the workforce. Union leader Roger Lyons said that ‘this is a devastating body blow to staff, who have acted impeccably in responding to the needs of the company to safeguard jobs over recent months’. But framing the losses as ‘equal opportunity’ job cuts caused union leaders some difficulty framing their opposition. ‘We will not be rushing to the barricades, but rushing to the negotiating table’, said TGWU leader Bill Morris: ‘On the basis of no compulsory redundancies and no attacks on our members’ terms and conditions, we will help to achieve a managed reduction.’

The unions’ commitment to British Airways’ ‘managed reduction’ denied workers an avenue for opposing the losses. Pointedly, a number of peripheral disputes flared up over seemingly unconnected changes, which were nonetheless a knock-on effect of the job losses, managed or not. In the summer of 2003, 2,500 check-in workers struck over the bringing in of a new computerised time-recording system, which they feared would lead to greater flexibilisation (read: irregular shifts). The check-in workers were mostly women, many of whom had taken on part-time work to meet domestic tasks, and were particularly angry about the disruption the system threatened.

In 2005 Gate Gourmet, a catering company at Heathrow that supplied British Airways’ meals, announced that it would sack 670 of its workforce, many of whom were Sikh women living in nearby Southall. A bitter strike followed that highlighted the oppressive working conditions of the South Asian workforce. In their eagerness to bring in equitable cost-cutting, British Airways had forgotten that it depended on less enlightened management amongst its contracted-out suppliers.

British Airways’ equal opportunity job cuts were a success for the company, but not really for the workforce. In years gone by an employer might well have leant on the racist and sexist thinking of the day to create a moral justification for the kind of cutbacks that they were making. But in 2002-03 British Airways sought to dress up their job-cutting exercise in rather different clothes. Opening up a discussion about the right way to lose jobs, they made it clear that the question of whether jobs would go was not on the table. These were equal opportunity redundancies, but they hurt, all the same.

Looking at the impact of the 1980s overall we can say that the working class has been unmade and remade. As left-wing commentator Richard Seymour says, it is ‘not your grandfather’s working class’. In 2013, one tenth of the labour force was made up of black and Asian people,60 and 46% were women. The recruitment of these additional workers has greatly enlarged the labour force. All told, these are profound changes.

As profound are the qualitative changes in the way the class of employees are organised. Trade union membership in Britain declined as the numbers in work have — over the long trend — increased. Union membership fell from its highest point of 13.2 million in 1979 to just over 7 million in 2013, from one half to one quarter of the workforce. The nature of union membership has been turned right around. Unionisation is most common where employers favour it. Most pay awards today are imposed, not negotiated. Unions act more often as advocates on behalf of individual members than they do as representatives of a collective will.

Running alongside those changes has been the growing acceptance of equal opportunities at work. The greater number of women and black people in the workforce has come as organised labour has had less influence. Equal opportunities policies have been extended just as the organisation of employment is less collective, and workplace negotiation has given way to a quasi-juridical relationship between employer and employee.

The marginalisation of the trade union movement is more than a sociological question. It says something about the existence of the working class as a class. In the 1980s, the ideology of socialism as a class outlook was effectively defeated, in the electoral and the industrial arenas. That outlook was core to working-class self-identity. Today some 60% of the population think of themselves as ‘working-class’.61 But today the identification does not mean identification with the labour movement, and is not allied to any social project. An appeal to ‘working families’ is a part of the rhetoric of all major parties, whether of the left or the right.

The greatest material consequence of the remaking of the labour force is the great increase in social inequality, as wages have failed to keep pace with the growth in output. In companies that are badged as ‘equal opportunities employers’, working people have seen their share of the nation’s wealth fall.