Sources of Discrimination Outside the Workplace

The movement in the direction of parity in pay, for women and minorities, has been painfully slow, and the goal is still not won. Reforms in the law, and reforms in company policy, have over the last 20 years levelled the playing field, but inequality persists. Activists, policy makers, and scholars have turned their focus to the discrimination that takes place outside the workplace, in wider society, as the anchor which makes equality at work so elusive.

Critics have pointed to the limitations of civil freedom outside or beyond civil society, limitations which make the freedoms within civil society into a mask for unfreedom. Carole Pateman explains that modern society is divided between two spheres, public and private, so that ‘the private sphere is typically presupposed as a necessary, natural foundation for civil, i.e., public life’ (‘but treated as irrelevant to the concerns of political theorists and political activists’, she points out). At the same time, she says, there is ‘the subjection of women within the private sphere’.1 Catharine Mackinnon makes a similar point when she says that ‘Women are oppressed socially, prior to law, without express state acts, often in intimate contexts’, adding that ‘the negative state’ — that is a liberal, hands-off state — ‘cannot address their situation’.2

Usha Prashar, Daniel Silverstone, and Herman Ouseley make a comparable argument when they say that ‘the view “treat them all the same” is quite discriminatory in its effects on different racial and cultural groups’. As they see it, ‘the notion of assumed equal opportunity for all has contributed greatly to the relative disadvantaged position of many black people’. More, ‘the “same for all” and “treat them all the same” approaches are major obstacles to achieving equality of opportunity, fair treatment and social justice’. They outline what they call ‘The System’, by which they mean ‘the organizational arrangements within large companies or institutions which determine how jobs are offered’. Their judgment is that ‘these bodies treat black people less favourably on racial grounds, because racism is an integral feature of organizational structures and individual attitudes’.3

These ways of looking at the question of equal opportunities make the case for positive action, over and above an ‘equal playing field’, because they identify forces that are outside of the ordinary considerations of who is best for the job as a persistent barrier to equality. The ideal of equality in the labour market is sabotaged before the position is advertised, they are saying.

The ways that the extra-economic foundations of discrimination are characterised are many. Many feminists have highlighted a patriarchal system in which power over women is defended and extended by men. Anti-racist activists have outlined what they see as a persistent institutional racism. These are explanations for the way that progress on equality at work has been so difficult.

Identifying the social factors that have stood in the way of equality has been a way of addressing those barriers. For some, though, talking up the limits to equality has turned from a positive programme of change to an excuse for its absence, or even a dogmatic insistence that change is not happening.

Without dealing with all the theoretical questions, we can identify the main barriers outside of work to equal opportunities at work. In this chapter first we will look at the trends in unpaid domestic work at home and its knock-on impact upon opportunities at work for women; second we consider the fraught question of national identity and the entrenched idea of a white indigenous people differentiated from the black other.

In both of these areas the course of events over the last 20 years suggests that many of the non-work bases of discrimination at work are in transition, and greatly diminished.

1. Work-Life Balance

In 1985 the Equal Opportunities Commission explained why it saw the question of equality at work closely tied to that of the burden of housework: ‘The Commission has recognised from the outset, a decade ago, that work and the family were inextricably linked’, stated the Equal Opportunities Commission in its 10th Annual Report: ‘inequality in the labour market was caused by, and in turn reinforced, an unequal burden of domestic responsibilities’. They were lobbying for extended parental leave and childcare, as a way of stopping job losses through pregnancy.4

A decade later they were making the point again, under the title ‘Reconciling Work and Family Life — Why Equality is Important’. ‘The difficulties of working parents and carers in balancing work and family responsibilities are major barriers to equality between men and women’, they wrote. Once again, they had in mind the weightiest family responsibility, childcare:

In dual-earner households, both partners need access to childcare, as may both partners in non-earning households. For couples with children, training or a return to the labour market is made more difficult by the absence of local childcare facilities.5

Childcare, as we have seen, was the main point that divided the Equal Opportunities Commission from the Conservative administrations between 1979 and 1991. There had indeed been a reduction in publicly funded nursery places.6 At that time many people thought that women with young children ought not to work — especially other women. It was a view echoed by the Prime Minister. Widening the question of equal pay to include social provision of childcare was a bold step beyond the Commission’s immediate responsibility for tackling discrimination at work.

One avenue that had been looked at was workplace nurseries. There had been some workplace nurseries in the Second World War, and the Greater London Council experimented with these. The Equal Opportunities Commission thought that workplace nurseries were ‘one form of childcare provision which both assist working parents and enable employers to recruited and retain qualified and trained staff’. They protested that these ought not to be a taxable benefit, backing a ‘workplace nurseries campaign’ which did win tax exemption. Workplace nurseries were opened at the Royal Mail’s Mount Pleasant Sorting Office, and at Goldsmith’s College, University of London. They tended to struggle to fill places, and these have now closed.7

The Commission kept up childcare on the public agenda. They commissioned and published a report, The Under-utilisation of Women in the Labour Market, written by Hilary Metcalf and Patricia Leighton, economists with the Institute of Manpower Studies. Identifying an untapped reserve of 6 million women not yet in the labour market, the authors found a major ‘constraint on those women who actually wish to work’ was ‘the cost and shortage of available quality childcare’. That was an issue ‘which is now at the forefront of national debate’, said the Commission:8 ‘Our message — that women and men should be encouraged to be effective and responsible employers and family members — has been disseminated far and wide round the country.’ Pointing out that that demand for labour was tighter, as the economy recovered towards the end of the Eighties, the Commission reported that ‘there has been heightened interest and awareness from all these quarters, notably employers wanting to know what is the best way forward on childcare’. It was at this point that the Commission raised the goal of a national framework for childcare — a formulation that put the case for government action without it sounding like town-hall socialism. ‘We see major contradictions in the Government policy in this area’, wrote the Commission: ‘the Government is keen to bring women into the workforce, but is unwilling to provide a national framework for childcare’. They welcomed the government’s giving childcare payments to lone parents on training courses, but demanded, why not ‘to women living with their husbands’?9

Commission chair Joanna Foster set out the position in a keynote speech:

Social policies are needed which reflect the changed reality of women’s lives, and of their families’ needs and experiences. A co-ordinated system of community-based childcare provision, both for under-fives and older school-aged children, is a prerequisite for equality of opportunity.

She went on to say that:

Only when such support is available will women feel free to choose fulfilment from work as well as home, and men feel free to see themselves as participating fathers, husbands, family members as well as breadwinners.10

The Commission’s advice, drawing on a report titled Parents, Employment Rights and Childcare by Sally Holtermann and Karen Clarke, was that ‘the cost to government of a phased expansion of subsidized child-care — including out of school care as well as nursery places — would be more than outweighed by savings in social security and increased tax revenue’.11

In 1996 the EOC, having ‘worked on the issue of childcare for many years’, broadened the campaign: ‘we decided that it was time to try to establish a consensus on the need for a national strategy on childcare’. They set up ‘a working group to discuss the issues around childcare, a partnership of 21 organisations representing a wide spectrum of interests and expertise’. The working group argued that ‘expansion in childcare provision’ will ‘bring major benefits to employers by helping widen the pool of skills which are available and by retaining the investment in the skills of their existing workforce.’ For the government Cheryl Gillan at the Department of Education and Employment listened sympathetically. They told her that the ‘the benefits to employers of a childcare policy’ would include ‘the recruitment and retention of committed and experienced staff’, ‘recouping more of their investment in training’, ‘reduced absenteeism’, and ‘improvements in employee productivity’.12

The Commission’s efforts on childcare did have some impact on even a Conservative government. As Julia Somerville wrote ‘in the context of anxieties about labour shortages, positive support came from the CBI, a number of large employers and House of Commons Committees’: ‘government responded with a number of initiatives, including expanding under-5 places in primary schools, sponsoring voluntary sector provisions, improving regulation of child-minding, encouraging employers to provide workplace nurseries… and introducing a childcare tax allowance’.13 The number of children under five attending pre-school education in state schools grew from 646,657 in 1989 to 768,112 in 1991. But that was not the only way that families were meeting their childcare needs. Sally Holtermann highlighted an ‘impressive growth in day care facilities for young children in the last few years’, in her 1995 report. She added that ‘the growth of nursery education in the maintained sector has been relatively modest’ and that growth had been almost ‘entirely in the independent sector’.14 Apart from any help from the government, women and men were making their own arrangements, creating a new demand for private nursery places and child-minders, so that ‘the decade saw a dramatic rise in the provision of under-five childcare in Britain’.15 In fact the ‘percentage of three and four year olds in maintained nursery and primary schools in England has increased from 44 per cent in 1987 to 56 per cent in 1997’.16

The policy that was developed by the Equal Opportunities Commission, and only partly yielded to by the Conservative administration under John Major, was the basis of the Labour government’s National Family Strategy from 1998. A marked expansion of childcare places was backed with government cash. Government paid for 17.5 hours of nursery provision for three to five year-olds, and many parents paid the extra. By 2001 there were 1,053,000 places for children, with day nurseries, childminders, play-groups and pre-schools.17 By 1999 three quarters of three to four year-olds were in a formal childcare setting, rising to 94% by 2004.18 Though there were good reasons to think that the Conservative-Liberal Democrat government that was elected in 2009 would cut back nursery provision, there were still in 2013 ‘273,814 childminder places and 1,023,404 nursery places’.19

From a very unpromising beginning, the case for an expansion of early-years childcare took off in the 1990s. By taking on greater responsibility for looking after children, the government was trying to lessen the domestic burden to help women into the workplace. To see how much of an impact it had, we have to look at what was happening to the way that men and women shared their time between work and housework, and between each other.

The domestic workshare overall

The BBC measured people’s time use since 1949, through questionnaires, a study which would have been abandoned if Essex University had not taken it over. The rough story is that in 1961 women did five times as much housework as men, whereas in 2005 women did two thirds of the housework. The time that men spend on housework has hardly changed, up from one and a half hours to one hour and 40 minutes; but the time that women spend on domestic work has fallen sharply from six hours and 15 minutes a day to just under three.20

The fall in women’s housework, then, is largely due to the fall in time spent on housework overall. Cutting back the time spent on housework is the condition for women to enter the workforce. The main change is due to the increase in childcare places — the responsibility that it is most pressing. Once the share of childcare shifted, so that young children spent more time in nurseries, women spent more time in paid work. For both sexes, the balance of paid employment and domestic work is directly inverse, the more you do of one the less you do of the other. Women and men do roughly the same amount of work, if you add paid and unpaid together.21

In the 1970s sociologists looked at the impact that labour-saving devices, like the vacuum cleaner, washing machine, and food mixer, had had on domestic chores. They were surprised to find that there was no apparent fall in the time that women spent on domestic chores. All that happened was that these gadgets soaked up more time in more activities. With hindsight we can see that the impact of labour-saving technologies on the home was limited by the sexual division of labour. Women who were largely excluded from the labour market used the gadgets to do more domestic work, not to reduce the time they spent on it. Today, the sexual division of labour has been altered, with women spending much more time in paid work. The potential impact of white goods on domestic work is realised in the fall in hours spent on it.22

One argument that weighed on the question of women’s responsibilities outside work was that of flexibility. The idea was that conventional labour contracts, with long, fixed hours, were a barrier to women with other commitments, like dropping off and picking up children from school. More flexible work patterns might be better for women. In her book About Time, Patricia Hewitt sets out some of the main ways that the standard working day has been adapted, such as part-time work and flexible hours — and the ‘zero-hours’ contract, job sharing, ‘term-time’ jobs (running alongside the school term), flexi-time, as well as weekend work and work in unsocial hours. All of these non-standard working-hour jobs have been taken up by people, mostly women, who need to meet responsibilities at home. From 1989 the civil service agreed with unions alternative working patterns with guarantees to protect part-timers from discrimination — within two years the number of women working part-time had grown from 5 to 14 per cent. Boots and B&Q have both offered ‘term-time’ working and other non-traditional hours for many years.23

The idea that flexible working is good for women is open to a pointed objection. If it can be argued that the world of work is made more amenable to women with family commitments, are those women not also being trapped in peripheral working environments? So it was that in 1992 the Equal Opportunities Commission recalled that it ‘has repeatedly voiced its concerns that the changes we have seen in the labour market and in particular increasing casualization and fragmentation will have a disproportionate impact on women’. Their question was: ‘Flexibility has been achieved but at what price?’24

Just four years later, though, the Commission was talking up the positive side of flexible working. ‘Both businesses and employees can benefit from the introduction of family-friendly employment policies which help the recruitment and retention of staff’, they said. Now it was argued that ‘Employers need to recognise the different working patterns of women and men in order to achieve the benefits of the flexible labour market’.25

Julie Mellor, chair of the Commission in 2000, argued that ‘forward-thinking employers realise they do not have a choice — without flexible working policies they will not attract and retain the best people’. In her vision non-traditional hours were important for all parents, because ‘work/life balance’ is a ‘critical issue for fathers as well as mothers’. Social historian Hugh Cunningham is more sceptical, judging that ‘however flexible work hours become they’re unlikely to produce a situation where women (and men) feel anything other than pressed for time’.26

The argument was about whether flexibility was helping women, or helping employers push them into a ghetto. ‘Women and men have very different attitudes to working time’, argues Patricia Hewitt, ‘a difference which directly reflects women’s double responsibility in the home as well as in the workplace’.27 Employers might make the workplace more ‘woman-friendly’ by scheduling work to fit women’s availability, or moulding work to women’s other commitments, but to do so was to reconcile women working with their disadvantage in the labour market. The problem can be seen in the Commission’s treatment of the question of the most straight-forward adaptation to family responsibilities, the growth of part-time work.

Back in 1978 the Baroness Seear was cautiously optimistic that ‘that flexible working hours are reasonably common among male and female white collar workers, but part-time working’, which she took as a positive for women, was not widespread. Seear said that ‘British industry can only benefit by using the full talents of the country’s workforce’. But even as she argued the case for more part-time work, the Baroness was well aware that ‘segregation of jobs into men’s and women’s work is still widespread in industry, and is one of the major obstacles to promoting real equality’.28

Lady Elspeth Howe, a former deputy chair of the Commission, gave a speech the following year at Brunel University, where she argued that:

[P]art-time work is a central issue in progress towards equality for women because it is one of the main ways in which women choose to work and because more and more people (men and women) are realising the usefulness of working hours which allow time for family or other responsibilities.29

The following year the Equal Opportunities Commission News carried a double-page spread, written up by journalist Judi Goodwin, ‘Scandal of the Low Paid Workers’. In it she argued that ‘though part-time work is often considered an easy option that suits a large number of married women, the pay and conditions of part-time workers invariably amount to slave labour!’ As Goodwin said, ‘the most striking change in the labour market has been the increase in part-time working, a trend which has been described as “The Part-Time Revolution,” and one in which women have played a major part’. Goodwin was drawing on a survey, written by Jennifer Hurstfield and published by the Low Pay Unit, The Part-Time Trap. As Goodwin explained:

With inadequate day care facilities for children, and the prevailing attitude of society that still expected a woman to take responsibility for household chores, three-and-a-half million women who want to work have little option but to take a low-paid part-time job.30

According to Goodwin, the Low Pay Unit and Dame Howe equal pay laws and other legal guarantees should bring part-timers’ hourly pay up to the level of full-timers.

The Commission was still highlighting, in 1991, that ‘4.6 million women work part-time, 2 million of whom earn less than the National Insurance lower earnings limit (£52 in December 1991)’.31 Britain’s deregulated labour markets had favoured the growth of part-time working, so that ‘in 1990, of the 13 million women in the European Community who were employed part-time, one third worked in the UK’. ‘Our economy is especially dependent on the part-timer’, explained the Commission, adding ‘83 per cent of whom in this country are female’.32

Though part-time work helped women to rejoin the labour force, it was not on equal terms. The gender pay ‘differential is even more marked for the many low-paid women who work part-time’, noted the Commission:

They are caught in the trap of doing ‘typical’ women’s work, which is traditionally seen as being of low value and gives fewer rights to the pay benefits and special allowances available to full-time workers.33

KFC job advert, 2016

The Commission again emphasised that part-time work was key for women who wanted a chance to earn in their own right. ‘Research shows that at a number of points in the life cycle, women would prefer to work part-time in order to cope with caring responsibilities, and many women and some men will continue to prefer part-time work for part of their working lives’, said the Commission:

Their dilemma is that in order to do so, many have to accept working in lower status occupations than their previous full-time jobs… Women who are employed on a part-time basis are much more likely to work in low-skilled, low status and low paid occupations than in higher status and higher paid managerial and professional jobs.34

Two years later, Commission chair Kamlesh Bahl told the Secretary of State for Employment Michael Portillo that ‘research showed that action is needed to encourage employers to adopt a high productivity, high quality strategy towards human resources and to improve the quality of part-time jobs’.35 It was a problem that was never wholly solved. The Commission continued to ask that employers should make work more woman-friendly, especially in terms of hours, while at the same time understanding that women’s greater representation amongst part-timers was a sign of their subordinate position in the labour market.

One answer to the question was put by Catherine Hakim, whose research first identified the segregation of women as a key factor in low pay. Hakim put the point the other way around, saying that when women choose to put their commitments to family first, it is wrong to see that as oppressive. If women choose domestic life over career, she was saying, it is wrong to dismiss that as ‘false consciousness’ on their part.36 The point was reiterated by writer Rosalind Coward in her book Our Treacherous Hearts. Coming at the subject as a feminist, with a successful career, she interviewed women about how they felt about leaving work to bring up younger children. Coward was intrigued to find that many women, well aware of the feminist argument, had chosen to withdraw, and that ‘women themselves desperately want to hang on to that central role in their children’s lives’.37 Perhaps the argument that Hakim and Coward were making was just a sign that women who were in the social position they were in preferred to see it their own choice, rather than one that was put upon them, and if they chose to make the most of it, then that is what people do. All the same, they raised a different way of looking at childcare as a responsibility in a society where, arguably, the task was not a marker of subjugation.

Maternity pay

In 1983 a breakdown of the General Household Survey, published by Equal Opportunities Commission, showed the unequal impact that children had on women’s and men’s working lives. Among couples where the woman was under 29, with no children, 72% worked full-time (a small number part-time). But if these couples had a child under four years of age, fully 63% were not working. Once the child was five, more mothers than not went back to work, though most of these worked part-time. The more children they had, the less likely women were to work full-time, and few women with children worked full-time at any age. It was a stark sign of the way that the priority of family limited women’s prospects for work. A second indicator is the gender pay gap. While there has been much more advance among younger women, those over 30 show a disadvantage in relation to men’s pay, which is greater the older they are. The evidence would seem to say that women can be on a level playing field with men, but that once children are born their careers will be derailed. It is for that reason that the women campaigners and the Equal Opportunities Commission paid special attention to the question of maternity pay and maternity rights at work.

William Beveridge’s welfare plan included a payment, ‘Maternity Benefit’, given to all mothers for 13 weeks. The plan pictured mothers as home-bound and the payment supported them there. The picture was changed with the Employment Protection Act of 1975 which brought in a statutory right to 18 weeks’ paid maternity leave (six weeks at 90% of full pay, the rest at a lower, flat rate) according to the Equal Opportunities Commission. There was also a right for women who had taken maternity leave to go back to their old job for up to 29 weeks after the day the baby was born — ‘a significant landmark in the relationship between work and the family’. In 1984 the government pushed back on maternity rights and ‘the Commission drew attention’ to an extension in the ‘qualifying period for protection against unfair dismissal from one to two years’. This would be a big problem because ‘many women cannot meet the two-year service requirement necessary to qualify for a number of maternity rights’.38

Around 1988 the Labour opposition put the government under sustained pressure over the low rate of maternity pay, in comparison to other European countries, highlighted in a European Commission report.

Though the government was embarrassed, the Equal Opportunities Commission did offer some good news about a ‘dramatic increase in the number of employed mothers’. They published a joint report with the Department of Employment and the Policy Studies Institute in 1991, titled Maternity Rights: The experience of women and employers.

‘More and more young women are combining motherhood and paid employment’, the Commission announced. The changes in the law helped, so that ‘by the end of the 1980s, 60% of women in work during pregnancy met the statutory hours and length-of-service requirements for the right to reinstatement’. The report’s findings ‘demonstrate unambiguously that there has been a revolution in the position of working mothers since the beginning of the 1980s’. What is more, ‘employers seem to be largely accepting of the change’ with only a tenth reporting any problems.39 It was a very positive, and possibly overstated, view. They did acknowledge that too few employers made definite plans to take women back after their maternity leave. Still, the results were important, marking the changing status of women in the labour market. After many years with little change, the Commission was in a position to report too that the pay gap was closing again:

Over the 10-year period to 1990 the New Earnings Survey showed that the average hourly earnings of women remained around ¾ of those of men, although there was some narrowing of the gap towards the end of the decade.40

Change came with the 1993 Trade Union Reform and Employment Rights Bill. That changed the way that statutory maternity pay was administered, so that now it was paid out by the employer, who could claim it back from the government. The new law met some of the problems that had been raised by the European Commission, though the EOC objected that ‘the burden of costs has been shifted to employers’ (the cost of administration, that is), raising fears that employers would evade their responsibilities. The Commission wanted ‘reform of the system of maternity rights with employers relieved of the burden of maternity pay’.41

Under the Labour government that took office in 1997 the Equal Opportunities Commission was consulted on ‘the Government’s review of maternity pay and parental leave arrangements’, which were ‘the main focus of the EOC’s work in this field’ in the year 2000-01. The major change for maternity rights was that they were to become ‘gender neutral’, parental rights, so that ‘450,000 new fathers will be eligible for paid paternity leave when it comes into effect in April 2003’.42 As it turned out, very few men took up their right to paternity pay, which is too low to make it worthwhile to leave work.43

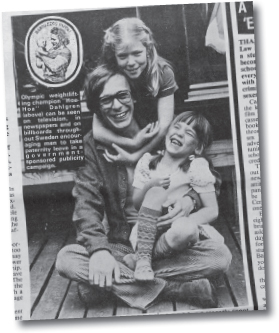

Swede Lars Jalmert taking paternity leave in the EOC News

The evidence from the time-use studies is that the share of domestic work is unequal, but less than it has been, and that the amount of time people spend on housework has been greatly cut back. (Perhaps surprisingly, parents are spending more of their leisure time with their children than before.) The fall in the amount of time spent on domestic chores is both cause and consequence of women’s much greater participation in the labour market. Also, the evidence shows that more women with young children are working and many of them are working full-time.

The changes have been spurred on and justified by the ‘business case’ for getting more women to work. But government also spent a lot to help women into work. For all the different ways of helping early-years childcare — tax relief on childcare vouchers, benefits for childcare, free nursery places — government was spending around £4.2 billion in 2012. A further £2.4 billion went towards statutory maternity pay — large-looking sums, though less than half a percentage point of Gross Domestic Product.44 As much as government spends, parents spend more on childcare and other costs. And families spend money to save time on domestic chores in other ways, spending nearly £30 billion a year on takeaway food and eating out.

With couples spending more time at work there were fears that this might lead to more family break-ups. Divorce rates did rise in the 1980s and 1990s, to around 150,000, or 14 per thousand married people a year. More recently, though, they have fallen back to around 10 for every thousand.

Women still do almost twice as much housework as men do, and while there are nearly as many women as men in work, two fifths of those are in part-time work (compared to 12% of men). The hourly pay gap between men and women has effectively closed for workers under 30 but beyond the age of 30 it opens up. One interpretation of that is that women will continue to lose out when children are born. On the other hand, the penalty for childbirth is less than it was. As women who might be earning more than their male peers have children, they are less likely to withdraw permanently from their chosen career progression. On paper at least, employers and the law are committed to protecting the station they have earned. ‘Average job tenure was falling for men’, the Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development found, ‘whereas it increased quite significantly for women’:

Improved maternity rights led to more women remaining with their employer after giving birth to a child and fewer women either leaving the labour market altogether or changing employers to find a job that suited their new circumstances.45

Moreover, the penalty that women face by leaving work to have a child is less marked when the model of a career for life is the accepted norm. As Beatrix Campbell argued:

The assumption that people want to change careers, that they want time out of work, that they want to learn new things, go to college, have kids, move in and out of the labour market, rather than stay fixed in one place for forty years, with a gold watch at the end of it, all of those transformations are associated with women.46

Those changes are associated with women, but they are more and more models for men’s employment, too. Overall, the evidence is that responsibility for domestic work is far less of a handicap to women’s prospects in work than it was. Time outside of work is perhaps more pressured than it was, where two partners are both at work. People are spending less time on household chores, but also more time with their children.

The law has changed to reflect the changing position of women in society. In 1990 the Law Lords were asked to clarify the position of rape in marriage. The eighteenth-century Law Chief Justice Hale had set down the dictum that it was not possible for a man to rape his wife, on the grounds that she had already given her consent in the marriage vows. In 1990 the Law Lords thought that was unsustainable, and that the common law is ‘capable of evolving in the light of changing social, economic and cultural developments’.47 There were other changes in family law, such as the 1976 law against domestic violence, the 1989 Children Act giving public authorities power to act against parental authority in favour of the interests of children, further family law in 1996 that included a rule for police to detain any accused of domestic violence and the 2015 law against coercive and controlling behaviour in a marriage. All of these signalled the end of legal support for the patriarchal family as a privileged sphere.

The gender division of household and workplace that rose to preeminence in the period 1850-1950 survives today only as a shadow of its former self.

2. Race and Britishness

Trying to explain race discrimination, people often talk about the way a society needs ‘scapegoats’ to blame; or the point is developed by saying that communities shore up their collective identity by fixing a group as ‘the other’. Put at that level of sociological abstraction, the argument is not so controversial. To look at the question of race in Britain historically, however, would mean seeing that the collective identity that was affirmed by emphasising the exclusion of black people was the identity of Britishness, which it might be more provocative to call into question. National identity, the assertion of a common British identity, for much of the twentieth century was understood as a white identity, with black people’s foreignness highlighted to make that point.

National identity was not just an ideological question, but an alltoo practical one for black people in the labour market. Large-scale black migration to Britain began in the 1950s with Afro-Caribbean and Asian labour recruitment. In the years that followed special laws to control immigration laid the basis for a two-tier labour market and a two-tier society. Officialdom treated black people differently from white, in the control of their movements, withholding citizenship status, demanding to see their papers, creating a special immigration police to track them, creating special detention centres for ‘illegal immigrants’, and in the assumption of the police that black people were to be treated differently, more harshly, because they were not a part of the law-abiding indigenous majority. All of these real manifestations of the second-class status of black immigrants in Britain were the basis for discrimination at work that was outside of work.

Race discrimination was ideological as well as being practical. It was bound closely to the idea of national identity. Discrimination was targeted at black people, but it was addressed to white people. The British elite were making an appeal to the wider white population, a promise that they were insiders, citizens. The real foundations of that national identity were the rights of citizens — their right to contracts to work or trade, to go freely where they wished, to organise to defend their interests, and to elect a government — all rights that were withheld to greater or lesser degree from black people. The long argument over national identity and British citizenship between 1945 and 1992 was an assertion of a community of interest between the working and the ruling classes. The foundations of that white national identity, though, were being undermined in the 1980s. The post-war consensus had recognised the participation of the working class as represented by the labour and trade union leaders in the ‘tripartite system’. That system was under attack in the 1980s, and effectively dismantled by 1992.

The reason that the assertion of national identity was so shrill and forced in the 1980s was that the basis on which one might have claimed a community of interest between white citizens and elites was being dismantled. The Conservative government of the 1980s appealed stridently to national identity, and implicitly to a white identity, just as — and because — it was down-grading the rights of ordinary Britons. Targeting black and Asian immigrants was a way of reasserting the virtues of British citizenship as they were being emptied of substance. In time these shifts would lead to a big change in the general ideas of nation and community, in which colour played an altogether different role.

All through the 1980s, while the Conservative government was taking apart those institutions and agreements that bound British citizens to the national project, that same government projected a strident nationalism. The government claimed to defend ‘British interests’ in its dealings the European Economic Community, and in the Commonwealth of formerly British colonies. Prime Minister Thatcher fiercely defended British prestige abroad, sending troops to fight Argentina for possession of the Falkland Islands, as she berated the leaders in Brussels for taking ‘our money’. This heightened call to nationalism added to the ill feelings towards foreigners and to immigrants settled in Britain.

It stands to reason that the Commission for Racial Equality could never accept the argument that black people were not British. The Commission saw its role as ‘to help and encourage the minorities to confidently take their full place in the mainstream of British national life’. The Commission was grateful for ‘the full commitment of this Government to the good race relations which are fundamental to the success of our British society’, from Conservative Home Secretary William Whitelaw. The Home Secretary went on to say:

[I]n the interests of the whole nation, and in particular to remove unjustified fears stirred up amongst ethnic minority groups, I wish to reaffirm the complete commitment of our Conservative Government to a society in which all individuals, whatever their race, colour or creed, have equal rights, responsibilities and opportunities.48

These words would ring hollow for the many who were asked to show their passports to get treatment in hospital, or singled out by their colour for special attention from the police, as well as those subjects of the British Empire who were refused the right to remain in Britain. The ‘interests of the whole nation’, ‘the success of British society’, seemed to be very much at odds with those of the black minority. They were denied a place ‘in the mainstream of British life’.

Over time, though, attitudes changed. One effect of the much tighter controls on immigration in the 1980s and 1990s was, as Julian Clarke and Stuart Speeden noted, that ‘the ethnic minority population is no longer immigrant’ — more and more of the black population of Britain were born in Britain, and the pretext for denying their Britishness was becoming more and more tenuous.49 As discriminatory as the Nationality Act was in its impact, the promise that those migrants who met its criteria would have their citizenship recognised did fix the idea that some Britons were black.

As we have seen, the growing number of asylum seekers shifted attitudes to black people in Britain.

Number of asylum applications received by year of application (including dependents)

| 2000 | 97,860 |

| 1999 | 91,200 |

| 1998 | 58,000 |

| 1997 | 41,500 |

| 1996 | 37,000 |

| 1995 | 55,000 |

| 1993 | 28,000 |

| 1992 | 73,400 |

| 1991 | 32,300 |

| 1990 | 38,195 |

| 1989 | 16,775 |

| 1988 | 5,739 |

Junior Minister Ann Widdecombe made the case for the restrictions on asylum-seekers’ rights in Britain, when she warned that the ‘opportunity to seek employment is a major incentive for economic migrants and undeserving asylum applicants’.50 Official measures to curb and control ‘asylum seekers’ from overseas, like the opening of the Campsfield detention centre, searches at ports of entry, and police raids, all heightened hostility to more recent arrivals to Britain.

MP Martin Salter, a member of Reading Council for Racial Equality and long-standing supporter of the anti-racist magazine Searchlight, contrasted his ‘ethnically mixed and proudly multicultural’ constituency with the ‘legally aided, corrupt abuse of the system’ by ‘deliberate overstayers’ and ‘stowaways’, who ‘can justifiably be regarded as economic migrants rather than refugees’. In Salter’s telling, his black and Asian constituents, ‘people, who are as British as I am, resent the fact that the debate on race and community relationships in this country has become skewed’; ‘Someone whose skin is brown or who wears a turban might now, somehow, not be regarded as British any more, but as just another of those asylum seekers’.51

The Commission for Racial Equality had relatively little to say about the new asylum laws, keeping its criticism at the level of generalities. ‘The questions being asked were “where is the fairness, where is the compassion, where is the justice?”’ summarised Herman Ouseley, who had just taken over as Commission chair.52

In his 1981 book, The New Racism, Martin Barker anticipated the way that racial discrimination could be dissociated from biological ‘race’ as such, and attached instead to cultural differences. With the ‘asylum seeker’ panic of the 1990s, prejudice against the foreigner moved further away from the expected associations of black and brown migrants to Britain and hardened against the new dispossessed from Algeria, Somalia, and later Eastern Europe. The black but ‘British as I am’ were rendered more like insiders, in this way of looking at the question. But the shifts in racial thinking were not exhausted by this contrast of the good black Briton and ‘bogus’ asylum seeker.

Teenager Stephen Lawrence was murdered by a gang of white youths in Eltham, South East London, on 22 April 1993. The case became a turning point in British race relations. The police inquiry was a farce, and it seemed likely that the killers would escape justice. A determined campaign by the boy’s parents, Doreen and Neville Lawrence, won the support of everyone from the Anti-Racist Alliance to the Daily Mail. This eventually led to an inquiry under Sir William Macpherson. Below we consider the conclusions of the Macpherson Inquiry, but let’s look first at the way the killing was seen.

Racially motivated killings, tragically, were not unheard of in Britain before 1993 and it seemed likely that Stephen Lawrence could become just another grim statistic. The family’s campaign to highlight their son’s death, though, struck a nerve. In the press the stereotypical image of violent black youths and innocent white victims was more or less reversed. Under the headline ‘INTO HELL’, Daily Mirror reporter Brian Reade went to a largely white housing estate in Eltham and ‘found racism seeping from every pore’ of this ‘E-reg Escort land’ where racial hate is ‘a way of life passed down from father to son’.53

The Lawrence killing became part of a new discourse on crime initiated by the future Labour Party leader, then Shadow Home Secretary, Tony Blair. Knowing that ‘law and order’ had been an issue that the Conservative Party had dominated Blair was set to make it his own, saying he would be ‘tough on crime’. Blair pinned the cause of crime on the free market and the way that it had destroyed community cohesion. Talking about the Stephen Lawrence killing, and about the murder by two children of the toddler Jamie Bulger, Blair painted a picture of large swathes of society in a state of lawlessness. Even Thatcher, no stranger to crime panics, was moved to protest that ‘crime and violence are not the result of the great majority of people being free — they are the result of a small minority of wicked men and women abusing their freedom’.54 Thatcher’s crime panics targeted outsiders and tended to reinforce Britishness as a positive, Blair saw crime as endemic in a sick society. The Labour politician hit a rich seam of middle-class fear, now expressed towards a burgeoning white underclass.

Music journalist (now novelist) Tony Parsons penned a vicious diatribe in the Daily Mail titled ‘Why I hate the modern British working class’ — ‘treat them like humans… they still behave like animals’ — and for Channel 4 authored a film on the same theme of denouncing the ‘lumpens… dressed for the track, but built for the bar’, called The Tattooed Jungle.55 Jack Straw, then Shadow Home Secretary, gave a speech in 1995 about the ‘Aggressive begging along with graffiti and in some cities “squeegee merchants” all heighten people’s fear of crime on the streets’, while radical journalist Beatrix Campbell writing about rioting in the North East and Liverpool in 1991 thought she saw a ‘culture of crime’ with ‘coercive coteries… founded on bullying, intimidation and exclusive solidarity’.56 These former socialists were venting their frustration on a working class that they felt had let them down. No longer the vehicle of socialism, the British working class was a big disappointment. These ways of thinking about the underclass were familiar to people who had paid attention to the racial insults thrown at black immigrants, except that now it was the white estate-dwellers who were being demonised, too. As Kenan Malik wrote at the time, paraphrasing the critics’ argument: ‘White yobbos, like black Yardies, are not part of civilised society.’ As respectable society would see it, said Malik: ‘Morally, socially and intellectually, the underclass, black and white, is inferior to the rest of us.’57

The coordinates of prejudice were shifting. Respectable society was not contiguous with white society any more. There were respectable black people, and less so, and there were degenerate white estates as there were good citizens. All of these prejudices floated on a very real social shift. The integration of organised labour into respectable society in the 1950s had come to an end as the century did. The furiously triangulating ‘New Labour’ party was putting a distance between itself and the working class in the 1990s as stridently as the Conservative Party had attacked them in the 1980s. The bond that tied the (largely white) labour movement to the nation state had been cut. All of that social change meant that the marked division between respectable white society and peripheral black migrants was breaking down.

‘In years to come 1998 will be seen as a watershed for race relations in Britain’, Herman Ouseley wrote as chairman of the Commission for Racial Equality: ‘No one will ever forget that it was the year of the Macpherson Inquiry into the racist murder of the black teenager, Stephen Lawrence.’ The Commission played its part in the lead-up to Macpherson’s report, and ‘felt impelled to put the issue on the public agenda and decided to launch a hard-hitting advertising campaign’: ‘Our aim was to raise awareness of the extent to which racial prejudice still exists in Britain today and to suggest that everyone can and should do something to stop it.’58

Sir William Macpherson’s conclusions were a considerable boost to the Commission’s view. The conclusions that stood out were that the Metropolitan Police investigation into the teenager’s death was compromised by the force’s ‘institutional racism’. It seemed to be a very hard-hitting phrase, one that was in common use among equal opportunity campaigners. The point of the term was to say that the problem of discrimination was deep-rooted, not just the matter of a few ‘rotten apples’ in the barrel. As he clarified the point, Macpherson made clear that he was not necessarily saying that individual officers were personally racist, but that they might unwittingly adopt practices that add up to institutional discrimination.

Macpherson’s report had the unexpected result of excusing individual officers of responsibility for failings. At the same time it opened up the police service overall to a level of scrutiny and criticism from which the establishment had previously pledged to shield them. If the institution was racist, then it needed thorough-going reform. What was more, the ‘report accepted the CRE’s submission that institutional racism was not an issue solely for the police service, but for every institution public and private’.59 Macpherson concluded that ‘If racism is to be eliminated from our society there must be a co-ordinated effort to prevent its growth’, and ‘this need goes well beyond the Police Services’.

Doreen Lawrence and Bernard Hogan-Howe

The Commission was pitched into the centre of public life, and the report’s ‘findings and recommendations have provided the CRE with a new framework for its work with organisations to eradicate racism and discrimination’. As they reported:

numerous copies of the CRE’s leaflet on the implications of the inquiry for racial equality were distributed within three months, and we were inundated with requests for advice from public sector organisations all over the country.60

The impact of the Macpherson Report was consolidated in a far-reaching new amendment to the Race Relations Act that came into force in 2001. ‘The amended Race Relations Act now includes all public functions’, reported the Commission under its new chair Gurbux Singh. ‘It gives some 40,000 public bodies in Britain a new, enforceable, statutory duty to promote racial equality and good race relations.’61

For the government Angela Eagle, Home Office minister for race relations, said:

The changes are aimed at the hearts and minds of organisations. The government wants public organisations to make race equality core to their work. These new measures build a robust framework to help public bodies provide services to the public in a way that is fair and accessible to all, irrespective of colour or ethnicity.

The focus was on public institutions, but the goal was to make race equality a core British value throughout society: ‘By placing the public sector at the forefront of the driver for race equality in British society, we hope to create a powerful lever to raise standards in all sectors of society.’62

The shift in attitudes at work that was initiated in the 1980s under equal opportunities policies had come to be a foundation stone of public policy in the ’00s. Some might object that these were rhetorical commitments, though in fact the changes were far-reaching, with public institutions committed to ongoing reform. A conference called to check on progress two years after the report concluded that ‘public authorities have a long way to go before they can say that their policies and practice are promoting racial equality’ — the Macpherson reforms were framed as a process, rather than a result.63

More to the point, the general declaration behind the 2000 Race Relations Amendment was that racial equality was an established goal of British society.

Community cohesion

As if to underscore the importance of the question of race relations, just as the authorities and the experts were talking about the ongoing reform of public institutions, ‘violent confrontations broke out between white and Asian people and the police in Oldham, Burnley and Bradford’ between April and July of 2001.64

Home Office Minister John Denham commissioned a report into the disturbances from government advisor Ted Cantle, of the Institute for Community Cohesion. Running alongside Cantle’s investigation, Herman Ouseley, having handed over the chairmanship of the Commission for Racial Equality, undertook an investigation at the request of the community and local government project ‘Bradford Vision’. Coming out of Ouseley’s and Cantle’s reports there was a debate about the merits of ‘multiculturalism’ that we look at in the next chapter. But here it is worth taking note of the proposals that Ouseley made coming out of the riots. He called first for:

A coherent response for Bradford’s public services (including the Police and all agencies) to meet their obligations under the new Race Relations (Amendment) Act 2000 and to promote social interaction and mixing.

Secondly, Ouseley hoped for:

Ways in which leadership at institutional, organisational and community levels must promote and carry forward the mission, vision and values for greater community, cultural and social interaction across the different cultural communities.65

These proposals read like timeless platitudes, and would hardly be remarkable read alongside the many local authority policies that Ouseley and others have authored over the years. What is noteworthy is that in the context that it was made this vision of ‘community cohesion’ was what stood in the place once occupied by national identity. Kyriakides and Torres call this policy ‘Third Way Anti-Racism’, showing that it comes out of the ‘Third Way’ political programme worked up by Labour party reformer Tony Blair. The ‘Third Way became a means by which the state attempted to relegitimise itself in a world without alternatives to the capitalist system’, they argue.66

In the technocratic language that was commonly adopted during the years that Tony Blair’s ‘Third Way’ government ruled, Ouseley’s abstract appeal to ‘community cohesion’ is doing the work that a more atavistic ‘national identity’ promoted under previous governments once did. It expresses a wish for social solidarity that would overcome division. In this version of ‘community cohesion’, though, people are not excluded on the grounds of their colour.

Where the Conservative governments of the 1980s and ’90s jealously protected British national interests, the Blair and Brown governments were much more sympathetic to transnational institutions like the European Union and the United Nations. At least in the way they explained themselves, they were not following selfish national interests, but rather working with other nations towards humanitarian ends. Tony Blair seemed to be a lot more comfortable among other world leaders than he did with the British public, and much of the elite derived more authority from inter-governmental agreements than they did from any popular mandate. Cosmopolitan internationalism rather than national sovereignty was the clarion call of the elite.67

The end point of the Macpherson report and the Race Relations Act that followed it was, paradoxically, that Britain became institutionally anti-racist. Formally, at least, its institutions were committed to the goal of racial equality. Whereas in the past the moment of ‘community cohesion’ would be exemplified in the national anthem, the flag and the Queen, post Macpherson, the value most leant upon to emphasise social solidarity was diversity and tolerance in a multicultural society. Just how successful that could be would be tested in the years that followed. Still, it is worth underlining that the substantial reassertion of national identity that so pointedly excluded black and Asian people in the post-war years, was by the new century officially inclusive and diverse.

Limits to equal opportunities

Frustration with the lack of progress on equal opportunities led researchers to try to understand the more deeply-rooted, social bases of discrimination beyond the workplace. Those were valuable explorations that highlighted the way that women’s unequal responsibility for housework on the one hand, and the institutional racism in British institutions on the other, worked against equality at work. To investigators it often seems as if the identification of these barriers shows that progress can only go so far, and that discrimination is as endemic as ever. To the contrary, though, the identification of these barriers to equality is itself a sign that they are being shifted.

It would be wrong to argue that discrimination has been brought to an end. No serious examination of the outcomes of the gender and ethnic pay gap, or employment prospects, would support such a conclusion. What is clear, though, is that many barriers that looked insurmountable are being moved.

There is a formula that activists used to explain — ‘oppression is prejudice plus power’. The saying was coined to show that prejudice is not just a psychological attitude, but one that can be powerfully reinforced by the social and institutional distribution of power. Today there are as many, if not more, prejudices at large in British society. On top of the mainstream prejudices of white and male superiority, there are a whole welter of misanthropic ideas about the underclass, alongside prejudices about asylum seekers and Muslims, as well as many ideas about the pathological collapse of masculinity. All of these prejudices are expressive of a less robust democratic culture in Britain, and the decline of the status of organised labour as a social partner.

What is less true of today, though, is that prejudice against women, and against black people, is reinforced by institutional power. Indeed, the one remarkable thing about Britain at the turn of the new century has been its institutional commitment to build an equal opportunities society.