Mainstreaming Equal Opportunities

Equal opportunities policies have come of age. No longer a nagging reform, they are at the heart of workplace relations in the twenty-first century. The project though holds itself to be unfinished. Dracula never dies, no matter how many times you kill him. So it is with discrimination. The policy needs a problem to address. Before we look at the problems that the equal opportunities policies throw up, we ought first to understand just how mainstream they are.

Mainstream is not just an adjective in the language of equal opportunities policies, it is a verb. Under the heading ‘mainstreaming’, the Equal Opportunities Commission pledged that it ‘is working to build equality considerations into all levels of government and all services’. As they said, ‘our objective is for the equality implications of all policy to be considered from the start of the policy-making process’.1

One example of how ‘mainstreaming’ works is the Athena SWAN charter. The charter works as a commitment on the part of universities and colleges ‘to advancing women’s careers in science, technology, engineering, mathematics and medicine (STEMM) employment in higher education’. Athena SWAN works as a kitemark or badge awarded at different levels to universities and colleges by the Equality Challenge Unit: Bronze, Silver, and Gold. Sponsored by the Royal Society, the Department for Education, and the universities, the Equality Challenge Unit encourages universities to change ‘cultures and attitudes across the organisation’, on the grounds that ‘to address gender inequalities requires commitment and action from everyone, at all levels of the organisation’.

These are laudable aims, but just as arresting are the means. The Equality Challenge Unit is a voluntary system of self-regulation on the part of the universities. It relies on the benchmark set by the charter, and on the competitive drive of institutions to match the standards achieved by rival universities. In practice it means that the charter is always the first point on the agenda of every meeting and decision — a formula that college administrations have adopted to earn their status as holders of the Athena SWAN Award, and to improve their rating, from Bronze to Silver, and on to Gold.

Universities have created the Athena SWAN charter, because it is a system of self-regulation that works — works both in the sense that it leads to consistent incremental advance towards a better representation of women in STEMM posts; but also in the sense that it works to give the organisations an overarching sense of purpose and reform. Lecturer Sara Ahmed, who worked on Goldsmiths College’s equality charter, worried that ‘the orientation towards writing good documents can block action, insofar as the document then gets taken up as evidence that we have “done it”’. Ahmed told the story of how her committee’s work on the charter was lauded by a new Vice Chancellor, who showed off the Equality Challenge Unit’s award to the College, ‘informing the university that it had been given the “top rank” for its race equality policy’, and thus ‘“We are good at race equality”’. ‘But those of us who wrote the document did not feel so good’, Ahmed explained: ‘A document that documents the inequality of the university became usable as a measure of good performance.’2

Television broadcasters have often been criticised for the way they side-line or caricature black people. Tony Freeth, Stuart Hall, and the Black Workers’ Association produced the show It Ain’t Half Racist, Mum for BBC2 in 1979 which highlighted the problem. In the 1982 book of the same name Tony Freeth wrote that ‘if there is to be significant change in the TV image of our black communities, there must be change in the production process’, adding that ‘there must be more black film-makers’.3 Channel 4 and BBC both enhanced their minority-ethnic programme making, and a Commission for Racial Equality study of minority representation on TV found that while Asians were under-represented in proportion to their share of the UK population, ‘black participants were more likely to be seen on TV than in the real world’.4 In 2001 the BBC Director General said that the organisation was ‘hideously white’ and its management 98% white. The industry’s Creative Diversity Network was founded by the major terrestrial and digital broadcasters to redress the imbalance. Amongst its many programmes are year-long placements for minorities amongst all the major commissioners. Channel 4 has committed itself to a 20% black and minority-ethnic workforce, and has also brought in Diversity Commissioning Guidelines — contract compliance for its independent television companies to employ minority production staff and talent. In June 2016 the BBC was criticised by MPs for advertising scriptwriting posts (for its drama Holby City) for black and minority-ethnic applicants only. The Corporation defended itself saying that the posts were training posts, and so covered by race equality law.5

‘Mainstreaming’ equal opportunities has been taken up by the institutions of the European Union, too. In 1998 the Council of Europe agreed that ‘Gender mainstreaming is the (re) organisation, improvement, development and evaluation of policy processes so that a gender equality perspective is incorporated in all policies at all levels’. The Council set up the European Institute for Gender Equality, which as Director Virginia Landbakk explains ‘has started working with selected tools which were considered good practice in the field of gender mainstreaming and at promoting gender equality’. What this adds up to is a commitment to ‘gender training’ — ‘building gender capacity, competence and accountability’, because:

Gender mainstreaming requires decision-makers and public servants to support the goal of increasing gender equality, be aware of the mechanisms reproducing inequalities in general, and possess the skills and power to modify the public intervention for which they are responsible.6

Behind all of the prolixity, the point of this programme is mostly a training programme, whose unspoken purpose is to socialise European policy-makers into a certain way of thinking. The EIGE listed a number of different bodies who had already undergone the training, including the Andalusia Regional Government, the Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions, the European Commission DG for Research and Innovation, the Provincial Government of Styria in Austria, and Women in Councils in Northern Ireland.

One sign of the way that equal opportunities have become ‘mainstream’ is the way that other claims have been folded into the model of equal opportunities that were developed in the first instance to address discrimination against black and Asian people, and against women at work. Davina Cooper, a Haringey councillor in the 1980s, explains that equal opportunities ‘provided a means of entry into the political agenda for lesbian and gay issues in the mid-1980s’, and that it ‘created an equivalence between identities — Black, female, disabled and homosexual’ — which, she argues ‘was frequently inappropriate’.7

The question of the rights of gay men was raised in the 1950s and ’60s as a question of civil liberties, by the Homosexual Law Reform Society and the Campaign for Homosexual Equality, leading to Lord Woolfenden’s 1957 report favouring reform, and the 1967 Act that partially decriminalised homosexuality (‘between consenting adults in private’ and with a higher age of consent, 21 years). The Gay Liberation Front formed in 1970 was very much an outcome of the ‘Sixties’ generation of radicals that had also founded the Women’s Liberation Front. The GLF’s goal was to change society, and liberate not just gay men but all people from narrowly heterosexist norms, and to fight the still markedly repressive policing of gay men.

The Gay Liberation Front took up the cause of homosexuals persecuted at work as but one dimension of the general campaign for freedom. Gay rights (which were by this time coming to be coupled in the formula ‘lesbian and gay rights’) were only taken up as a specifically ‘equal opportunities’ campaign once the idea of equal opportunities for women and for black people had been set out. Principally, it was among the municipal left that inclusion of lesbian and gay rights at work came to be included in the equal opportunities policy. In the Spring of 1983 the Greater London Council announced its new Grievance Procedure in respect of discrimination: ‘You can now take action against discrimination on grounds of sex, race, colour, nationality, ethnic or national origins, sexual orientation, age, trade union activity, political or religious belief.’8 The inclusion of sexual orientation reflected the discussions that were taking place in the Women’s Committee at County Hall, and the growing lobby for lesbian and gay rights among the municipal activists. In 1985 Phil Greasley published the book Gay Men at Work, ‘A Report on discrimination against gay men in employment in London’, with a foreword by the ‘out’ Labour MP for Islington South, Chris Smith.

Discrimination at work was without doubt a problem for lesbians and for gay men — as was discrimination in other settings too. However, there was no obvious sense in which lesbians or gay men as a cohort occupied a distinctive role in the workforce, as was the case with women and black people. Were gay people penalised in the labour market? What evidence there is seems to suggest that lesbians and gay men had average incomes higher than the average for the country.9 Folding the rights of lesbians and gay men into the equal opportunities policy was one way that the logic of equal opportunities at work was coming to define liberation movements. The activists of gay liberation were reinterpreting their struggle as one of workplace discrimination to fit the preoccupations of the time. One councillor and gay rights activist despaired of the combative way that the issue had been raised, saying ‘the gay issue has been dragged in by well-intentioned councillors who think it is the same as sexism and racism, when it’s not, without realising the forces ranged against it’.10

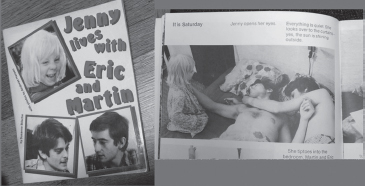

Demonstration against Clause 28

That said, there was shortly afterwards a pointed struggle over gay rights that was indeed focused on the workplace, and that was the clash over Section 28 of the Local Government Act of 1988. The row took place in Haringey, after the education office circulated a booklet for schools called Jenny Lives with Eric and Martin, designed to familiarise children with the possibility that a child’s carers — parents — might be two gay men. The council offices were picketed by an unhappy ‘Parents’ Rights Group’, who did not want their children taught about homosexuality, which in their minds was associated with paedophilia. At the prompting of Dame Jill Knight, the Conservative government included the clause in its local government bill that forbade the ‘promotion of homosexuality’, and teaching the ‘acceptability of homosexuality as a pretended family relationship’ in schools. Large protests against the bill galvanised the lesbian and gay rights movement. Beatrix Campbell pointed out that Haringey Council was imperious in its attempts to bring about lesbian and gay equality from on high: ‘in the absence of any public work within civil society, statism has replaced consciousness-raising’, was the way she put it. She was right. As chair of the group Council Workers Against Clause 28, I helped to organise a day of action to oppose the government attack on gay rights. An officer in the Council’s Lesbian and Gay Unit, who went round the council offices asking clerks for their support with me, berated those who were not sure, demanding to know why they worked for the Council if they did not support its equal opportunities policies. As she saw it, the task was to enforce compliance from employees, not to win over fellow workers to take solidarity action. In the way these things work out, when the bill became law, it was the Lesbian and Gay Unit itself that was tasked by the Council to ensure that its discriminatory clause was enforced. The contrast with the school secretaries in the local government union NALGO was marked. They were mostly working mothers and many were anxious about measures they saw undermining the family, and opening their children to undue sexual knowledge. On the other hand, they could see that those teachers who were gay would be open to persecution under the law, and voted to oppose it.

The Section 28 episode showed that lesbian and gay rights did not really fit into the argument about equal opportunities at work, but was part of a larger, more ideological debate about the sanctity of the family, and the presumed pressures upon it. Section 28 stayed on the statute books from 1988 until 2003 when it was repealed (three years earlier in Scotland). Around that time governments of left and right moved quite quickly in the direction of lesbian and gay rights to equalise the law of consent (Sexual Offences Amendment Act, 2000), to outlaw discrimination (Equality Act (Sexual Orientation) Regulations, 2007), and eventually to legalise gay marriage (Civil Partnership in 2004, followed by the Marriage (Same Sex Couples) Act in 2013). The swift and surprising liberalisation of the laws on lesbian and gay rights comes about because, unlike the transformation of the position of women, gay rights do not require a reorganisation of the social order, but rather reflect the changing ideological position following on as ‘family values’ came to carry less weight.

Muslims in Britain

Over the last 20 years Britain’s Islamic minority has been in the spotlight. Muslims in Britain had been addressed in social policy not as Muslims, but as a subset of an ethnic group, Asians (allowing that there are a small but growing number of ethnically European converts). The main Muslim populations in Britain have come from Pakistan (43% of the total), India (9%), Bangladesh (17%),11 and more latterly from North and East Africa; as well as a smaller group from Arab nations. There are around three million Muslims living in Britain. Official policy to Muslims was not friendly or hostile, but the hostile attention to Asians by the immigration and police services, as well as by employers, often focused on Muslim beliefs and cultures.

In 1978 Dr Muhammed Iqbal and a member of the Home Secretary’s Advisory Council on Race Relations argued the case for separate schools for Muslim boys and girls in the Commission for Racial Equality’s newsletter, New Equals. Dr Iqbal understood the fear ‘that separate schools for Muslim girls and boys may perpetuate under-achievement, hence alienate school-leavers from single-sex institutions from jobs commensurate with their attainments parallel to the English’. As he saw it, ‘Westernisation may well bring about the desired results in terms of job opportunities’. But he asked ‘what about the resultant and internecine secularisation, irreligiousness, materialism, pseudo-individualism and erosion of moral values?’12

Since the Khomeini revolution in Iran in 1979, the British state has often been in conflict with states and movements motivated by militant religious-political ideology in the Middle East, and these have had an impact on relations between Muslims, the authorities, and the wider population in Britain.

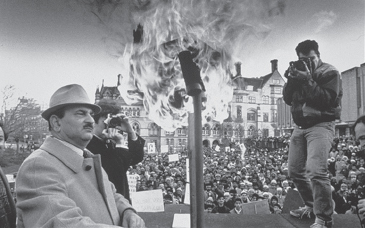

In 1988 British Muslims in Bradford protested at the satirical picture of the prophet set out in British-Indian author Salman Rushdie’s novel The Satanic Verses. The cause was taken up by an imam in India, and then by the Ayatollah Khomeini, spiritual leader of the Islamic state in Iran, who issued a ‘fatwa’ or judgment against the apostate author, to the effect that it was acceptable to kill him. How rhetorical or serious the fatwa was, was open to question, but his Turkish publisher was killed, and Rushdie was allocated an armed guard by the British government. It was a moment when many Muslims in Britain came to organise around their religious identity more than their Asian heritage (the popular Muslim News, for example, was launched shortly afterwards).13

Increasing conflict in the Middle East, with British and American military intervention in Lebanon (1984), Libya (1986), the Persian Gulf (1988), two wars in Iraq (1991, 2003), and a prolonged participation in the occupation of Afghanistan (beginning in 2001), as well as British support for the Israeli occupation of Palestine, all added to the heightened tension between radical Islam and the British authorities. Terrorist attacks by small groups of radical Muslims against Western targets — most notably the World Trade Center in New York on 11 September 2001, but followed by bombing attacks in London on 7 July 2005 — heightened tensions between the authorities and British Muslims.

As well as the growing evidence of atrocities and torture carried out by British security services abroad, security measures to cope with ‘home-grown’ terrorism provoked anger. Anti-terrorism laws allowed for much longer time for those arrested to be interrogated before being released, for special orders imposing home curfews for ‘terror suspects’ and scores of early morning raids, and deportations of individuals — often to countries where they were at risk of torture.

The alienation of some Muslims, who were drawn to agitating for, and in some cases participating in, terror attacks against British targets, disturbed the British authorities. Alongside the surveillance and repressive measures undertaken against Muslims suspected of terrorist conspiracies, the British government has tried to build bridges with the broader Muslim population to reinforce more moderate beliefs. British support for mosque committees goes back to before the 1976 Act and the Community Relations Councils founded under the 1965 Act.

Mala Sen went to a day ‘Conference of Bangladeshi Youth’ organised by the Federation of Bangladeshi Associations and the Asian Centre in Islington in 1977, where ‘a young Bengali, from the local Bangladesh Youth Association, stood up and criticised’ their elders: ‘we were not consulted’, he said in Bengali, ‘This thing has nothing to do with us. You’ve only come down here because you want to control us — you want us to follow you.’ As Sen saw it back then, ‘Unabashed, the elders, all of them professional community relations wallahs, proceeded’.14

Back then the generation gap saw younger Bangladeshis organised on the basis of their ethnic identity, in a political lobby, the Asian Youth Movement. In 1981, 12 members of the Asian Youth Movement were arrested and tried on conspiracy charges, after they organised to defend themselves and their community against racist attacks. Through the Commission for Racial Equality’s grants to CRCs and through local government, the authorities shored up the influence of the mosques as a counter to the influence of the more political radicals. ‘In March 1994’, explains Kenan Malik, in the wake of the protests over The Satanic Verses, ‘the Conservative Home Secretary Michael Howard appealed to Muslims to form a “representative body” that he could “support and recognize”’. Before then the Foreign Office had been supportive of Saudi-backed Muslim groups. In 1997 the Muslim Council of Britain under Iqbal Sacranie was founded.15

With Islamist movements inspiring more people around the world than radical nationalist movements did, the generational divide among British Muslims looked a bit different. The secular challenge of the Asian Youth Movement had fallen away. Instead young Muslims challenged their more moderate elders on the terrain of belief. The traditional religious identification that the authorities had encouraged became a battleground between radicals and moderates. When the congregants at the Finsbury Park Mosque, swelled by refugees from the civil war in Algeria, embraced the teachings of radical Abu Hamza it became a focal point for Islamists, until Hamza was forced out. In 2003 the security services raided the mosque.

Burning The Satanic Verses, Bradford, 1989

Attempts to win over ‘moderate’ Muslims have led to more financial aid for mosque-based organisations that the government hope can act as interlocutors, like the Muslim Council of Britain. In 1997 the government changed the law so that Muslim schools could be stateaided along the same lines as Jewish, Catholic, and Church of England Schools. Some, though, have argued that the government’s policy of funding religious organisations has tended to promote ethnic division. Kenan Malik explains that the government’s preferred interlocutor, the Muslim Council of Britain, is in fact quite marginal to most Muslims and, being associated with the Pakistan-based organisation Jamaat-i-Islami, what most commentators would call ‘radical’. As Malik says, ‘if the prime minister believes that he can only engage them by appealing to their faith, rather than through their wider political or national affiliations, who are Muslims to disagree?’ After the ‘7/7’ bombings in July 2005 the government distanced itself from the MCB, thinking that it had not done enough to contain radicalism.16

Other than direct representation through Mosques and Muslim groups, British Muslims have tended to be Labour voters, and after some kicking back Muslims have won some standing in the Labour Party. In the 1990s Birmingham’s nine sitting Labour MPs were all white though many of the party’s voters and activists were Muslims of Pakistani origin. A membership fraud committee under Clare Short went through the party lists checking all the ‘Muhammeds’ they found there. Some popular Labour Party organisers of Bangladeshi background, like Jalal Uddin and Lutfur Rahman, were overlooked when parliamentary seats became available. In time some of these activists peeled away from the Labour Party to find a better welcome in the far-left RESPECT Coalition, the Liberal Democrats, or in Lutfur Rahman’s case, setting up his own Tower Hamlets First Party. To the embarrassment of Labour, George Galloway won the Bethnal Green seat for RESPECT in 2005, with a large base of Bangladeshi support (a performance he repeated in the Bradford West by-election in 2012). Lutfur Rahman’s Tower Hamlets First Party won control of the Council in 2014, but less than a year later was controversially thrown out of office by the electoral court on grounds of ‘corruption’. When the electoral court handed its investigation over to the Metropolitan Police they judged that there was not enough evidence to carry on. In May 2016, Labour’s candidate for the London Mayor Sadiq Khan beat the Conservative Party’s Zac Goldsmith. Goldsmith was widely seen to have run a scurrilous campaign that tried to smear Khan as a friend of terrorism. Khan’s own slogan, though — ‘the British Muslim who can beat the extremists’ — turned out to be very popular. The bond between Muslims and the Labour Party has been made strong again.

British Muslims are on average less well-paid, less economically active, and in less skilled posts than the rest of the population. They are overrepresented in the hotel and catering trades, and as cab drivers.17 The think-tank Demos highlighted the statistical evidence that on average Muslims in Britain are less likely to hold a managerial or professional position, and that ‘Muslims in England and Wales are also disproportionately likely to be unemployed and economically inactive’. Demos’ report ‘Rising to the Top’ proposes a number of measures, including a plea for employers to:

Do more to prevent discrimination and reduce the perception of discrimination — with the Government and organisations such as the CBI encouraging them to undertake contextual recruitment as part of their graduate recruitment process.18

The Demos report follows from the Runnymede Trust’s 1997 proposal for monitoring of religious affiliation in employment and national statistics with a view to taking action to stop discrimination against Muslims.19 The evidence that prejudice against Muslims has led to greater inequality is suggestive — though it is not easy to distinguish the effects of discrimination on racial grounds from those on religious grounds. The Employment Equality (Religion or Belief) Regulations of 2003 ‘extended legislative protection to individuals on the grounds of religion or belief’ in the ‘areas of employment and training’. The Commission for Racial Equality ‘argued that new legislation should be introduced to give protection to individuals on the grounds of religion or belief not only in the area of employment, but also in provision of goods and services.’ The Commission

also considered that the introduction of new legislation to prohibit the incitement of religious hatred was necessary to protect individuals who were becoming increasingly vulnerable to verbal and racial attack, but who were not also protected by legislation that prohibited incitement to racial hatred, again due to the definition of racial groups.20

In 2006 Parliament passed the Racial and Religious Hatred Act, which largely expanded the definition of race hatred to encompass hatred against Muslims and Christians (Jews and Sikhs had both already been categorised as ‘races’ for the purpose of previous legislation). Some objected that the law would make proper criticism of religions illegal, that these were bodies of thought, not racial identities, which ought to be open to criticism.

Whether Britain’s problematic treatment of its Muslim minority can be dealt with as a matter of extending anti-discrimination policy and enlarging the meaning of equal opportunities at work is not clear. What is clear is that the authorities have a problem persuading younger Muslims to identify with British society.

Disability rights

Long before disability was ever addressed as a question of rights, British society, like most others, had undertaken the care of the disabled as a charitable imperative. Edward Rushton’s ‘school for the indigent blind’ was founded in Merseyside in 1791 after many lost their sight to smallpox.21 Handicapped people in Britain were cared for in special schools like Chailey School in East Sussex. From 1944, under the Disabled Persons Employment Act, the government supported factories and workshops run by a dedicated corporation, Remploy, which opened its first factory in Bridgend in Wales in 1946, eventually managing some 83 factories around the country. From 1963 the Spastics Society ran workshops and day centres for people with cerebral palsy. Care and help for the disabled was for many years a voluntary activity undertaken by churches, Rotary Clubs, and the Variety Club.

In 1976 the Union of the Physically Impaired argued for a new way of looking at disability, which they defined as:

[T]he disadvantage or restriction of activity caused by a contemporary social organisation which takes no or little account of people who have physical impairments and thus excludes them from participation in the mainstream of social activities. Physical disability is therefore a particular form of social oppression.

The British Council of Organisations of Disabled People, launched in 1981, did a great deal to promote what they called the social model of disability, and to campaign against segregation and stigmatisation. The more activist approach to disability gave a lot of people with disabilities a greater dignity, and sense of ownership of their issue. In 1986 the British Association of Social Workers adopted the social model of disability and it has been influential in the bringing of disabled students into mainstream education, who would otherwise have been segregated.

The social model, though, is not wholly true. Physical disability is physical disability. Social action, whether attitudinal, or in the provision of ramps and other material infrastructure and equipment to mitigate disability, cannot overcome serious disability. Mainstreaming has many good outcomes, but in cases of serious disability, such as autism and blindness, mainstream schools and workplaces can only do so much to accommodate. The influence of the social model of disability, though, has led governments to move away from special schools and employment for the disabled. Both the Blair and Cameron administrations oversaw the winding down of Remploy with the loss of thousands of jobs for disabled people, the last three factories in Blackburn, Sheffield, and Neath, South Wales closing in 2013.

One of the more controversial interpretations of mainstreaming and the social model of disability has been the Conservative government’s determination to get thousands of people off of incapacity benefit and into work. Lord Freud lauded the approach of government action ‘to support people with health conditions and disabilities into work’ and said that ‘we want to ensure that we spend money responsibly in a way that improves individuals’ life chances and helps them to achieve their ambitions, rather than paying for a lifetime wasted on benefits’.22 The system of interviewing and reviewing claims under the workfare scheme has widely been seen as an attack on disabled welfare claimants.

Men’s rights and ‘Rights for Whites’

As a rhetorical response to equal opportunities policies aimed at helping women and ethnic minorities, some of those who had been thought of as privileged have tried to frame their ambitions in the language of equal opportunities. In a well-publicised exchange in a House of Commons Committee in October 2015, Tory MP Philip Davies asked for time to be set aside for a debate on a proposal for an International Men’s Day, just as there was an International Women’s Day. Labour MP Jess Phillips was withering, saying ‘as the only woman on this committee, it seems like every day to me is International Men’s Day’. Nonetheless men’s rights campaigners have lobbied for greater access to children in divorce settlements as well as organising seminar series for picking up and dominating women. For the most part men’s rights activists have been dismissed as creeps or weirdos.

There had been a different sort of ‘men’s movement’ proposed in the late Seventies. The second national conference organised by Men Against Sexism took place at the Abraham Moss Centre in Crumpsall, Manchester in 1979:

the 50 workshops spread over the weekend included the experience of fatherhood and child care; rape; the need for national men’s campaign; therapy groups; sexuality; how feminism affects your daily life; and theoretical analyses of the role of men.23

The conference decided that a national men’s campaign was not what they wanted, and no further conferences were planned. Later some researchers and activists argued that the damage done to men by changing gender relations, and by the ideology of masculinity, needs to be addressed. Books by Roger Horrocks (Masculinity in Crisis, 1996), Anthony Clare (On Men: Masculinity in Crisis, 2000), Susan Faludi (Stiffed: The Betrayal of the American Man, 1999), and R W Connell (Masculinities, 1995) all talked about the difficulties that men were having reconciling the ambition to domination in the ideal of masculinity, with the decline in the status of men.24 Campaigners Diane Abbott, the Hackney MP, and feminist Laurie Penny both took up the call for action. ‘We still don’t have any positive models for post-patriarchal masculinity, and in this age of desperation and uncertainty, we need them more than ever’, wrote Penny, while Abbott deplored what she imagined to be a culture of pornography, ‘Viagra and Jack Daniels’ on offer to men.25 Not surprisingly few men took up this offer of an investigation of post-patriarchal masculinity. It seems unlikely that any call for a men’s movement will be anything but a movement that blames women for the problems that individual men confront. But perhaps that is to be expected when the model for the negotiation of modern life is as a series of competing claims in a zero-sum game.

‘Rights for Whites’ was a slogan adopted by the far-right British National Party in the early 1990s, around the time that it won a seat on the Tower Hamlets Council for the Millwall ward. The BNP played on some feeling that white residents had lost out in the allocation of council services to Bangladeshis. The seat reverted to Labour at the next election. Investigating rioting in Bradford in 2001 Herman Ouseley found that ‘many white people feel that their needs are neglected because they regard the minority ethnic communities as being prioritised for more favourable public assistance’. While Ouseley was a bit sceptical about the claims, some in the Committee for Racial Equality took note. Chair Trevor Phillips, in a television programme for Channel 4 and the associated press publicity, argued that many of the assumptions of redressing inequalities were wrong, and said for example that ‘non-white school-leavers are more likely than their white peers to head for university’, and that ‘poor whites are the new blacks’.26 In the programme Phillips pointed to the way that some schools were taking the kind of remedial measures to make sure that white working-class children prospered that once had been reserved for minorities.

The feeling that Britain’s white working-class communities were losing out lay behind the remarkable vote in a referendum on Britain’s membership of the European Union in June 2016. While most of the country’s business and political leaders called for a vote to stay in the Union, widespread disaffection in the country among the less well-off led to a majority vote to leave. For the ‘Remainers’ it seemed as if there had been a revolt of the ‘left-behind’ against the multicultural society.

Whether men, or whites, considered as a group, could ever be the target of positive action on an equal opportunities model is hard to work out. The arguments for equal opportunities were always imagined as correctives to the advantages that whites and men had over black people and women respectively. ‘Rights for whites’, or ‘rights for men’ — by their controversial nature — seem to be claims that call into question the universalizability of the equal opportunities model.

Overall the equal opportunities model, in coming to fruition, has invited different groups to make claims within its logic. More recently, for example, transgendered individuals have been included in workplace policies over discrimination, and in 2016 the Women and Equalities Minister Maria Miller has been looking at legislation to help. Miller could not help but notice the outcry of protest from people that she said were ‘purporting to be feminists’ over the inclusion of transgender people’s rights. But the transgender lobby is in many ways itself a creation of the logic of equality of opportunity. Inclusion in the list of those whose discrimination must be addressed is important for those individuals because it is the way that their broader social status is recognised.

The generalisation of the case for equal opportunities, its adoption by business as equal opportunities policies, and the greater legislative framework supporting their adoption, was beginning to have some strange consequences for the special Commissions dedicated to them.

In Lewis Carroll’s book, Sylvie and Bruno Concluded, the author has fun imagining a country where:

‘[W]e actually made a map of the country, on the scale of a mile to the mile!’

‘Have you used it much?’ I enquired.

‘It has never been spread out, yet,’ said Mein Herr: ‘the farmers objected…’

With Britain largely committed, at least on paper, to the ideal of equal opportunities for people of different races and genders, the question of why you needed a special commission to advance the case was bound to come up. Or as Carroll’s Mein Herr explains ‘we now use the country itself, as its own map, and I assure you it does nearly as well’.

At a conference called by the Local Government Information Unit, ‘Equalities’, held in 1991, Gurbux Singh, who was then Haringey Council’s Chief Executive, argued that the dedicated equal opportunities units that had been pioneered by Lambeth and adopted by local authorities all over the country ‘were no longer appropriate’. What was needed was ‘mainstreaming’, getting all the local authority departments to ‘take responsibility for equalities work’.27 Singh’s approach caught on, and the race, women’s, and lesbian and gay units were closed. Haringey councillor Davina Cooper saw the changes as evidence of a downgrading of the importance of equality work. In some senses it was, as the revolutionary tide of ‘equal opps’ was giving way to more practical generalisation of the model. At Channel 4, Commissioner of Multicultural Programming Yasmin Anwar made a similar point, saying that the real success would be when there was no need for multicultural programming.

The question of what the role of the Commission for Racial Equality would be in a country that had ‘mainstreamed’ equal opportunities was one that Gurbux Singh himself had to address, when he took over as its chair. Under Singh the Commission had some campaigns to carry on with, like one over the problem of rural racism. Talking about the 2000 Race Relations Act, Singh said that it was ‘to make equality (as much as “value for money” and efficiency) an essential part of the way public services are conceived and delivered’. There was a private-sector focus, too, with the formation of a new business advisory group that was ‘inaugurated in July 2001 to discuss policy and strategy with leading British businesses’:

Our aim was to create a forum where ‘critical friends’ could air their concerns. The group is made up of representatives from IBM, Shell, BP, Landrover, British Airways, HBOS, Barclays Bank, Lloyds TSB, J P Morgan and HSBC.

These initiatives were not a marked departure from the way that the CRE had worked since David Lane and Peter Newsam’s day, except that all of the businesses that were signed up had by this point had equal opportunities policies in place for 15 years or more. The participating companies were those which were seeking to show their support for the government’s initiatives. Most of them would in different ways, particularly at the time of the banking bailout in 2008, be grateful for the government’s support in the years afterwards.

One initiative that the Commission sponsored was called ‘The Leadership Challenge’:

In signing up to the Leadership Challenge, individual leaders make a personal commitment to promote racial equality, both in their own organisation and more widely, through their sector, and to drive the creation and successful implementation of a corporate racial equality action plan.

The initiative was launched by Chancellor Gordon Brown in a speech in 1999. Brown told the assembled business leaders: ‘this process — clearly nothing more than good practice — needs to become the ordinary way of doing business. This won’t happen by itself — you as leaders need to make it happen.’28 The business challenge was notionally about race equality, but substantially it was about business leadership, and a platform for motivational waffle of the kind that was so influential then. ‘There is a duty upon all of us in positions of leadership’, said Prime Minister Tony Blair, ‘to try and offer a lead to everyone else. That includes government itself, and I am happy to take up the Leadership Challenge and to acknowledge that we’ve got more to do to make progress.’29 Only very tangentially was the Leadership Challenge about race at all. It was really about geeing up business leaders, creating a sense of a cadre, with a mission and common goals.

The Commission for Racial Equality’s work, like that of the Equal Opportunities Commission, was drifting. They no longer occupied the position of custodians of an ideal, or advocates for change. The changes that they had embodied were, by the new millennium, taken on by most people in Britain as if not an unalloyed good, at least the right direction to be going in. In May 2004, the government published a White Paper, ‘Fairness for All’, ‘outlining its proposals for a Commission for Equality and Human Rights (CEHR) to replace the existing race, disability and sex equality commissions, with additional responsibility for religion or belief, sexual orientation, age and human rights’. The Commission for Racial Equality put up some resistance, but broadly the position was won without much argument. By comparison to the outcry over the vague threat to the CRE in 1981, when the Labour government wound up the Commission, it went almost unremarked.30

On 1 October 2007 the Equality and Human Rights Commission was set up, with Trevor Phillips as its first chairman. At the time of writing the chair is David Isaac, a lawyer and former Chair of the LGBT campaign Stonewall. The Commission takes up a broad range of issues, from those of travellers’ rights to the impact of legislation on victims of domestic abuse. Its campaigning role, though, has proved more diffuse and less controversial than that of either of the two Commissions that it replaced.