Pre-game nerves. Race-day jitters. Unabating thoughts of choking. A thumping heart. These are all manifestations of competition stress and anxiety, and many athletes—from recreational ballers to Olympic champions—experience these symptoms regularly. The effects of competition anxiety undoubtedly extend to the gut. As an example, one of the more common symptoms associated with stressful competition (or anxiety from a job interview, first date, etc.) is butterflies in the stomach, a ticklish or fluttering feeling in the abdomen. (The exact physiology behind this fluttering is a mystery, but it may have to do with changes in gut blood flow and nervous system activity.) Athletes nervous about an upcoming game or race are known to be stricken by other gut symptoms like nausea/vomiting, abdominal cramping, and unrelenting urges to use the privy.

While the gut is often thought of as being distinctly separate from the brain, the connections between these two parts of your body run deep. As I detailed in Chapter 1, your gut is home to between 100 million and 600 million neurons, which is one reason it’s referred to by many scientists as the body’s “second brain.” These connections allow important information about what’s happening in your gut to be relayed to your central nervous system. Likewise, information flowing in the opposite direction—from your central nervous system to your gut—allows your body to prioritize how resources such as blood and oxygen are utilized during times of stress. Like any elegant system, your gut-brain connection is prone to glitches. Experiencing too much stress, excessive anxiety, or a traumatic event can muck up this intricate system.

Before we dive into the science on gut-brain-mood connections in sports, I want to reiterate that I’m not a psychologist or neuroscientist. I have degrees in dietetics and exercise physiology and am a credentialed registered dietitian. So why, then, did I decide to devote an entire section of The Athlete’s Gut to these gut-brain-mood connections? The main impetus for including this information is that I have personally experienced glitches in these mind-gut connections, both in the context of sports and in everyday life. Like many people, I have mild general anxiety, but my most impactful run-ins with anxiety have been in performance situations. In high school, these symptoms were most severe during basketball season. Performing in front of a crowd, in combination with a fear of letting down other players on my team, were the roots of my anxiety. My uneasiness wasn’t usually intense enough for others to notice, but I sometimes found myself overthinking decisions during games, which is generally not advantageous during fast-paced sports like basketball.

My competitive sporting days are largely a thing of the past, but there are still occasions when I have to perform professionally (scientific conferences, media interviews, etc.). Most of the time I come off sounding calm and collected (so I’ve been told), but that’s not always the case underneath the surface, particularly in the moments leading up to these performances. As one saying goes, people are a lot like ducks, calm on the surface, but paddling like the devil underneath. I sometimes experience the gastrointestinal symptoms that accompany anxiety in these situations, including indigestion and mild abdominal cramping; however, it’s the cardiovascular and respiratory manifestations of my anxiety—along with my distorted thoughts—that are most unsettling. A slight tightness in my chest, feeling mildly short of breath, and a thumping heart are the physical expressions, while thoughts like “What happens if I can’t control these symptoms?” pop into my head, which ultimately exacerbates my physical symptoms. Ninety-nine times out of a hundred these physical symptoms and thoughts abate once the performance begins, but on a couple of occasions they’ve gotten the better of me, leading to a less-than-stellar presentation. Over the years I’ve learned to deal with my performance anxiety through a combination of strategies, but I still occasionally struggle with it. The fact is, I will probably always have some of these thoughts and symptoms leading up to professional performances.

As someone who conducts scientific research, I’m fully aware that having firsthand experience with something doesn’t automatically make you an expert on that topic. Case in point, there are scores of internet “experts” and “gurus” selling nutrition products and services based on their personal stories. Many of the claims made by these modern-day charlatans are devoid of science. That said, my own encounters with anxiety prodded me to explore the scientific links between the gut and the mind, and because of my established interest in sports science research, I eventually ended up combing through the literature in an attempt to find studies documenting exactly how anxiety and stress influence gut function before and during sporting competition. Although I came across a plethora of research on competition-related anxiety, I found, to my utter surprise, few studies that directly examined how mood states and gut symptoms are connected in athletic competition. To me this was shocking given all the anecdotes of competition-related nerves propelling athletes to puke before games or make frequent trips to the loo.

A recent high-profile anecdote of this sort of experience comes from a professional American football player named Brandon Brooks, a guard for the Philadelphia Eagles. In a 2018 Los Angeles Times piece written before the 52nd Super Bowl between Brooks’s Eagles and the New England Patriots, columnist Bill Plaschke described Brooks’s struggle with competition-related anxiety. In addition to stating that Brooks usually pukes before every game, Plaschke wrote:

“There was a time this fear triggered vomiting all day and night, causing him to miss the game. He has been sick enough for teammates to surround him in prayer, and for team doctors to send him to a hospital where he would watch those teammates on TV with his head stuck in a bowl.”1

After missing several games and taking a trip to the hospital, Brooks was diagnosed with an anxiety disorder, which he revealed to the world despite the tough-man culture ingrained in American football.

Brooks’s incidents with anxiety and vomiting are obviously on the extreme end of the spectrum of possibilities, but he’s by no means the first pro athlete to deal with competition-related anxiety powerful enough to induce vomiting. NBA legend Bill Russell purportedly vomited before almost every game of his professional career, and during one playoff game, Celtics coach Red Auerbach allegedly demanded his team leave the court during warm-ups and return to the locker room because he hadn’t yet heard Russell toss his cookies.2 NFL Hall of Famer Steve Young also reportedly suffered from anxiety-induced vomiting. Although Young was the league’s defending Most Valuable Player in 1993, he found himself vomiting before a game against the Atlanta Falcons, which largely stemmed from his fears of disappointing others and replacing the legendary Joe Montana.3

Ultimately, the goal of the third part of this book is to explore what’s behind a case like Brandon Brooks’s, as well as the gastral misfortunes of countless other lesser-known athletes who have dealt with an angry gut that’s the by-product of competition-related stress and anxiety. In this chapter, I review the concept of stress and how it relates to health, athletic performance, and gut function, which is followed by a discussion of the connections between anxiety and these same outcomes.

STRESS

Stress is a fundamental, inevitable part of life. Yet for many of us, the word stress evokes mostly negative connotations. It’s true that too much stress can be harmful to your health and performance, but it’s important to remember that stress is your body’s response to any demand placed on it. This generalized, purposefully vague definition of stress was first proposed by Hans Selye, an Austro-Hungarian endocrinologist considered to be the father of the modern biomedical stress concept.4 Selye’s thoughts on stress can be succinctly summarized with an oft-used quote from his thousand-plus-page doorstopper, Stress in Health and Disease:

“Stress is not something to be avoided. Indeed, it cannot be avoided, since just staying alive creates some demand for life-maintaining energy. Even when man is asleep, his heart, respiratory apparatus, digestive tract, nervous system and other organs must continue to function. Complete freedom from stress can be expected only after death.”5

As with most sweeping theories, not everyone agrees with Selye’s take that stress is best viewed as a nonspecific response.4 Regardless, there is universal agreement that stress is a necessary part of life. What’s also true is that persistent elevations in certain types of stress are damaging to health and performance. For example, heightened psychological stress in the workplace or stress that’s a result of a traumatic life event have been linked to ailments such as stroke, type 2 diabetes, and obesity.6–8

In athletes, the acute psychological stress that bubbles up before and during competition is ubiquitous but doesn’t necessarily have a predictable relationship with performance. Among other reasons, this is because of differences in how stress is defined and measured in studies as well as the variability in how individual athletes appraise the manifestations of stress. As an example, one athlete might perceive a pre-game elevation in heart rate as a positive signal that their body is prepping itself for the challenge to come, while another athlete may view this same response as a disturbing lack of control over their bodily functions.

Despite the inconsistent associations between acute competition-related stress and performance, long-term elevations of stress—especially if they’re perceived by an athlete to be negative—are dependably linked with injuries and overreaching syndromes.9 These connections are so reliable that in 2006 the American College of Sports Medicine (in conjunction with several other medical organizations) published a consensus paper with the following statement about the impact of stress on injury:

“Personality factors (e.g., introversion/extroversion, self-esteem, perfectionism) and other psychological factors (e.g., a supportive social network, coping resources, high achievement motivation) alone do not reliably predict athletic injury risk. . . . However, there has been a consistently demonstrated relationship between one psychological factor—stress—and athletic injury risk.”10

So even though direct relationships between stress and athletic performance are rather unpredictable, it’s obvious that an injured or sick athlete is one who can’t perform at her peak. Thus, it behooves coaches and practitioners to pay close attention to sources of stress in their athletes’ lives.

It’s not completely understood how psychological stress contributes to injuries in athletes, though there’s no shortage of hypotheses. One possibility is that stressed athletes aren’t paying close enough attention to what’s going on in the midst of competition, which, in sports like American football and rugby, could lead to being blindsided by an opposing player. To a certain extent, this hypothesis is supported by experiments showing that under stressful conditions, athletes tend to have wandering eyes, and they fixate more on unimportant cues in their visual fields.11

An alternative proposed mechanism involves hormone fluctuations, particularly in cortisol, a steroid-type molecule produced in your adrenals. As an anatomy refresher, your adrenal glands sit atop your kidneys and look curiously similar to the bicorne hat that Napoleon once donned. Undoubtedly, cortisol is the hormone that most of the public associates with stress, and the internet is saturated with articles with alarmist-sounding titles like “Cortisol: Why the ‘Stress Hormone’ Is Public Enemy No. 1.”12 Despite its poor public reputation, cortisol’s functions are notoriously difficult to generalize about, as they often depend on the health of the individual, the tissue targeted by the hormone, and how much of (and for how long) it is secreted. What’s more, cortisol levels vary with your circadian rhythm, which is a phrase used to describe any biological process that displays an entrainable 24-hour pattern. Cortisol rises upon wakening in the morning, followed by a nadir in the evening. When you also consider that cortisol secretion can vary markedly from day to day in the same person, it’s easy to understand why it’s so difficult to establish a baseline blood cortisol level for someone. Think of traffic patterns as an analogy; clearly, it would be foolish to assume that the flow of traffic on a freeway at 8:00 a.m. is reflective of what traffic is like at 10:00 p.m.

To address this cortisol measurement conundrum, researchers can take multiple blood or saliva samples from a person, but that’s particularly challenging to do in large studies that aim to understand the links between exposures (such as cortisol) and diseases/injuries that develop over weeks, months, or years. Scientists have begun to work around this obstacle by analyzing samples from tissues that are believed to reflect long-term cortisol levels (i.e., human hair), but even with this improvement in analytical methods, relationships between cortisol and health aren’t always straightforward. Take the findings of a comprehensive review published in Psychoneuroendocrinology, which concluded that although hair cortisol levels were higher among individuals living with chronic pain, depression, and a history of major life events (suggesting they experience more chronic stress), levels among people with anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) were often lower than in healthy subjects.13

Exactly why people with chronic anxiety and PTSD would have diminished cortisol levels is uncertain, but one possibility is that they’ve developed an overly sensitive feedback response.14 The hypothalamus and pituitary gland are the prime regulators of cortisol production by your adrenal glands, and when your cortisol levels get too high, your hypothalamus and pituitary gland respond by pumping the metaphorical brakes on its production. This pumping of the brakes—known as negative feedback inhibition—contains your stress response and prevents it from spinning out of control. Under situations of prolonged, elevated stress, however, the hypothalamus and pituitary may become overly sensitive to cortisol, leading to excessive braking and a state of chronic hypocortisolism (low cortisol levels). While this is a workable hypothesis, another conceivable explanation for the links between hypocortisolism and PTSD and anxiety is that low cortisol levels predispose people to developing these conditions. Long story short, the connections between cortisol and health are surprisingly complex.

With that tangent about the measurement of cortisol out of the way, let’s return to the more relevant question at hand. Do elevated cortisol levels predict injuries in athletes? The short answer is no. The more complicated answer is that we don’t yet fully know, as few longitudinal studies have looked at this question.15 Considering the totality of evidence, however, there’s little reason to believe that excessive cortisol secretion is directly responsible for the development of most injuries and illnesses in athletes.

So if cortisol doesn’t clearly explain the higher rates of injuries and illnesses among chronically stressed athletes, then what does? As a scientist, I’m trained to recognize that it’s foolhardy to expect a simplistic explanation for a complex phenomenon. This certainly rings true to me when it comes to explaining injuries and illnesses in sports. With this caveat in mind, there’s at least one convincing explanation for the greater risk of one type of “injury” in stressed-out athletes: suppression of the immune system. Even in nonathletes, it’s been recognized for at least 50 years that chronic stress and major life events often precede the onset of respiratory tract infections and other minor ailments,16, 17 but it wasn’t until years later that scientists began to understand the specific immune changes that occur in response to sustained stress. I won’t go into the specifics of these immune changes, but there are loads of studies showing that almost every aspect of immune function is affected by chronic stress. As one scientific review that assessed three decades of research put it, “The most chronic stressors were associated with the most global immunosuppression, as they were associated with reliable decreases in almost all functional immune measures examined.”18

This state of immunosuppression helps explain why stressed-out athletes often have the sniffles or reoccurring colds. It might also explain why these athletes often don’t return from physical injuries as quickly as expected, as the immune system is directly involved in healing.19 In one frequently referenced study, two small wounds were made on the roofs of the mouths of dental students, the first of which was timed during a low-stress period (summer vacation), while the second was timed during a high-stress period (three days before the students’ first exam of the term).20 Even though both wounds were the same size to start, it took the students 40 percent longer to heal during the exam period. Of course, there are other potential explanations for the different healing rates (diet, exercise, sleep, etc.), but additional studies have produced similar findings in other populations, bolstering the case that chronic stress impairs healing.21

In contrast to the prolonged kind, psychological stress that lasts minutes to hours can actually boost immune function, a point articulated by Firdaus Dhabhar, esteemed stress researcher at the University of Miami. Dhabhar thoroughly outlined the evidence for this immune-boosting effect of acute stress in a paper published in Immunologic Research, arguing that it makes sense from an evolutionary perspective for the body to prioritize immune function during and after stressful situations because they often (at least thousands of years ago) resulted in wounds, injuries, and infections.19 Dhabhar reasoned that the process of evolution would be unlikely to select for a system that would allow a person, in his words, “to escape the jaws and claws of a lion only to succumb to wounds and pathogens.”

To summarize, a simple way to think about psychological stress is that, when it’s experienced in sufficient doses over multiple days, weeks, and months, it can impair health, healing, and physical recovery. Contrary to what is often reported in media stories, cortisol isn’t the most important culprit responsible for many of the harms associated with stress. In reality, there are likely several ways by which sustained stress negatively affects your health and recovery, one of the most important being the suppression of your immune system.

STRESS AND GUT FUNCTION

One of the most powerful ways that exercise affects your digestive tract is by constricting gut blood flow. Both intense and prolonged exercise result in a profound shift in blood flow away from your gut, toward your skeletal muscles and—especially in hot and humid environments—toward your skin. As it turns out, psychological stress can also redirect blood flow away from your gut.22, 23 (Although if it’s only mild in nature, stress has little impact on gut blood flow.24)

Over the past few decades, advancements in ultrasound technology have allowed scientists to noninvasively probe how gut blood flow changes with a variety of stressors, including those that are psychological in nature. However, you might be surprised to learn that these shifts in gut blood flow were documented almost two hundred years ago. In 1822, a Canadian fur trader named Alexis St. Martin was accidently shot with a musket, resulting in a hand-sized wound that, once healed, still left an opening large enough that a person could see directly inside St. Martin’s stomach.25 William Beaumont—the physician stationed at the site of the accident—initially treated St. Martin but didn’t think he would survive. St. Martin did manage to pull through, and Beaumont saw an extraordinary opportunity to study what had long been out of the reach of scientists: the inner workings of human digestion.

Of course, Beaumont’s dreams of studying the mysteries of digestion and becoming a world-renowned gastric physiologist hinged on St. Martin’s willingness to serve as more or less a human guinea pig. Fortunately for Beaumont, St. Martin was unable to pay his hospital bills and agreed to work and live in Beaumont’s home as an indentured laborer. As a part of this Odd Couple–like arrangement, St. Martin allowed Beaumont to conduct more than two hundred gastral experiments on him over roughly a decade. Among other things, Beaumont inserted and extracted small muslin bags filled with various foods into and from St. Martin’s stomach and even stuck his tongue inside the hole in St. Martin’s side. (How else would you figure out how the inner coating of the stomach tastes?) Beaumont’s mini-studies—the results of which were published in his book Experiments and Observations on the Gastric Juice and the Physiology of Digestion—were pioneering in that few others had successfully probed the process of digestion in humans.26 Beaumont’s book paints St. Martin as somewhat of a cantankerous figure, although if you keep in mind that he was subjected to hundreds of mildly unpleasant experiments, you can hardly blame St. Martin for his irritability. This may also help explain why St. Martin was prone to overindulging in alcoholic beverages on occasion. In one entry, Beaumont writes:

“St. Martin has been in the woods all day picking whortleberries. . . . Stomach full of berries and chymifying ailment, frothing and foaming like fermenting beer or cider; appears to have been drinking liquor too freely.”26

Among the discoveries that arose from his experimentation on St. Martin, one of Beaumont’s most interesting revelations was that a person’s psychological state influences how much blood flows to their stomach. Specifically, Beaumont observed that “fear, anger, or whatever depresses or disturbs the nervous system—the villous coat becomes red and dry, at other times, pale and moist.”26 These changes in appearance from red to pale (and vice versa) were almost certainly the result of alterations in blood flow to St. Martin’s visceral organs. In St. Martin, Beaumont had, quite literally, a gastric window into the man’s state of mind.

Over the next 150 years, other cases of patients with permanent openings into their digestive tracts corroborated Beaumont’s observation that mood state impacts gut blood flow. One such patient, a man known as Tom Little, had an artificial opening into his stomach surgically created after his esophagus was permanently damaged from swallowing scalding hot clam chowder at the age of 9. In 1941, a pair of physicians, Stewart Wolf and Harold Wolff, convinced the then 56-year-old Little to serve as a subject in a series of tests focusing on psychosomatic changes and gastric function. Stewart Wolf later recalled the following about their experimentations on Tom Little:

“The exposed gastric mucosa of Tom made it possible to observe the vascularity of the stomach. . . . In Tom and in other fistulous subjects . . . we found that fright, depression, and attitudes of being overwhelmed were associated with pallor of the mucosa.”27

When you pair the information gleaned from historical cases like Alexis St. Martin and Tom Little with the revelations from contemporary studies, it’s impossible to deny that an individual’s psychological state influences blood flow to the gut.

Aside from its effects on gut blood flow, psychological stress can also influence smooth muscle activity in the gut, otherwise known as motility. In particular, stress can tone down stomach motility,28 and one of the first scientists to document these alterations was Walter Bradford Cannon, a leading American physiologist of the early 20th century. During some of his experiments, Cannon noticed that young male cats were restive when restrained while older female cats remained mellow, and that these differences in temperament corresponded to differences in stomach activity. He further observed that “by covering the cat’s mouth and nose . . . until a slight distress of breathing is produced, the stomach contractions can be stopped at will.”29 In an experiment conducted years later, Cannon went so far as to place a barking dog near a restrained cat and then proceeded to take blood samples from the cat to see what effect the “excited blood” had on a strip of intestinal muscle. (It caused a relaxation, or a reduction in motility.30) As it relates to athletes, attenuated stomach motility could exacerbate upper gut problems like nausea, fullness, bloating, and reflux, especially when they’re trying to consume sizeable quantities of food or fluid in and around the time of competition.

In contrast to the dampening of stomach activity, stress can result in a livelier colon. Early experiments undertaken by physician Thomas Almy at New York Hospital in the 1940s and 1950s documented that simply discussing emotional topics could abruptly throw the colon into spasm. In a 1949 article, Almy describes measuring colon motility in patients as the researchers led them through discussions of unsettling life events.31 Almy used a latex balloon placed in the colon to measure pressure changes, which gave him an indication of muscle activity. In a constipated German housewife, for instance, colon contractions intensified when, as the researchers put it, she “expressed resentment over her husband’s ability to have regular bowel movements.” (Of all the things you could take umbrage at your spouse for, focusing on his propensity to defecate seems peculiar.) In another case, the colon of a 26-year-old man went into a frenzy after he revealed that a woman he had been seeing “humiliated and scorned him for his inability to satisfy her sexually.”31

In another article, Almy and his colleagues describe going to even greater lengths to manipulate colon function in an unlucky medical student referred to simply as L. L.32 After positioning a proctoscope in L. L.’s lower colon, the researchers carried out an elaborate deception to make him believe he had a potentially cancerous lesion. The researchers told L. L. that they had to take a biopsy (even though they never took one), and during this time the motility of L. L.’s colon became progressively more intense. After 20 minutes of dupery, the researchers finally fessed up and told L. L. the procedure was fake. In the associated paper, Almy and his coauthors state that L. L. accepted their reassurances that nothing was truly wrong and that L. L. held no “resentment for the . . . anguish he had been through.” Despite Almy’s proclamation, something tells me L. L. wasn’t completely bitter-free about this skullduggery.

The effects of stress on colon motility observed in Almy’s eccentric experiments have largely been confirmed in more contemporary studies.33, 34 To put it plainly, psychological stress can make the colon go wild. It’s somewhat puzzling, then, that the symptoms arising from a more active colon vary drastically. In many cases, cramping and urges to go numero dos are stimulated. In others, constipation and bloating are more prevalent. Thinking about it logically, one would assume that frequent and strong contractions of smooth muscle would translate to a heightened urge to poo, but it really depends on whether those contractions are coordinated and propulsive or of a spastic variety. (Experiencing spastic, uncoordinated smooth muscle contractions in your colon could mean you’re headed for constipationville.) That said, anecdotes about having to defecate before stressful competition seem to be reported with more regularity than constipation.

Interestingly, humans have the power to consciously override nerve-induced urges to poop in many situations, but animals that are of a less-inhibited nature are much less capable. As it turns out, rats are particularly inclined to poo when stressed, and, anecdotally, exposing a rat to a new environment (such as a maze or a living space) is a good way to get said rat to empty its bowels. If you’re not big on anecdotal evidence, you’re in luck, as an experiment carried out in the 1930s found strong correlations between rats’ emotional responses (measured via their willingness to eat in a strange enclosure) and their proclivities for defecating.35 Much like rats in a cage, the psychological stress and anxiety experienced by athletes before endurance races is undoubtedly one reason lines for Porta-Johns are often as long as those for the latest and greatest ride at Disney World. Unlike rats, though, humans can usually keep it in long enough to avoid making a public mess.

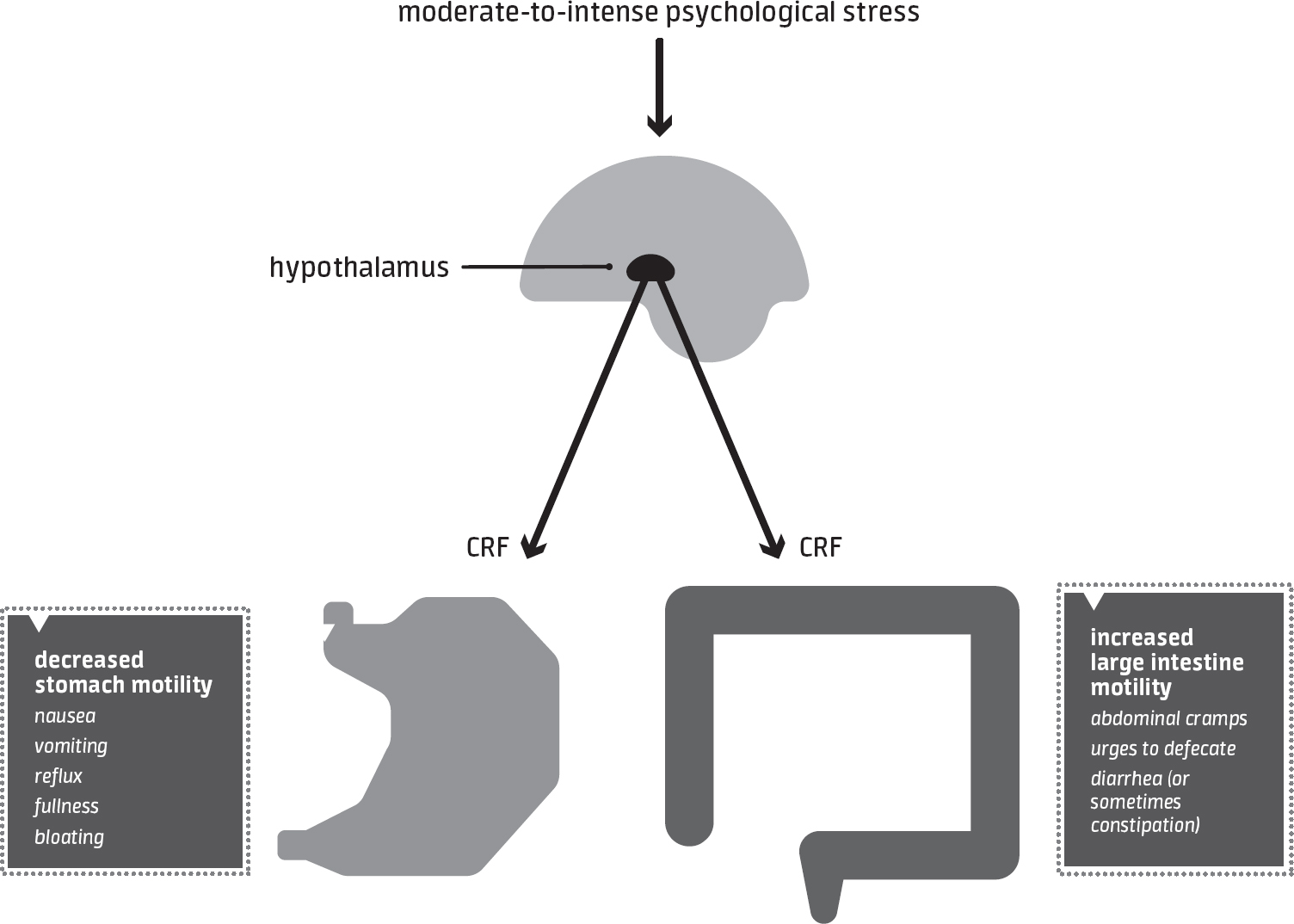

There are a few physiological explanations for why reduced stomach motility and amplified colon activity accompany acute psychological stress. One of the most consistent scientific findings is that a hormone called corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) contributes to the ebbs and flows of gut activity.36 Your body responds to stress by secreting CRF from your hypothalamus; CRF then binds with receptors in your brain that modify the activity of your autonomic nervous system, the primarily unconscious part of your peripheral nervous system that helps control gut function. Across a variety of studies, directly administering CRF to animals dampens gastric motility and acid secretion while it also spurs colon motility.36, 37 The role of CRF in provoking gut symptoms with psychological stress is presented in Figure 11.1.

During times of extreme psychological stress, these motility changes and their associated symptoms become commonplace. Few situations are as stressful as what soldiers experience during combat; in contrast to the run-of-the-mill pre-competition jitters experienced by many athletes, absolute fear is the emotion soldiers often feel before and during combat. In some cases, this fear is associated with spontaneous defecation; in an article in a long tome titled Encyclopedia of Violence, Peace, and Conflict, the authors report that one-quarter of World War II veterans admitted to defecating in their pants during combat.38 In these situations, CRF secretion almost certainly contributes to a colon and rectum that are—to put it in layman’s terms—massively overstimulated.

Urgent impulses to poo and the nervous shits are common manifestations of acute severe stress. With respect to the other end of the gut, nausea represents an equally troublesome stress-invoked symptom. The secretion of CRF plays a role in triggering said nausea, but there’s another hormonal response that may be as equally influential: the release of catecholamines. High-intensity exercise, altitude, and—most directly—injecting catecholamines all increase blood catecholamine levels and can provoke nausea. Although I didn’t cover this extensively in Chapter 2, acute psychological stress is also a source of catecholamine secretion. Many studies have demonstrated psychological stress’s effect on catecholamine secretion, but I’ll focus on one that used what’s called the Trier Social Stress Test, a task that’s become the gold standard for examining psychosocial stress in the lab. Though variations exist, the Trier Social Stress Test typically subjects participants to a mock presentation in front of a panel (often presented as a job interview), followed by a challenging arithmetic task (e.g., counting backward from a large number by increments of 13). In the example study I’m focusing on, participants had plasma levels of the stress hormone norepinephrine (also called noradrenaline) measured before and after the Trier Social Stress Test, and as expected, norepinephrine levels shot up, with levels ending up about twice as high as they were beforehand.39

figure 11.1HOW ACUTE STRESS AFFECTS THE GUT

Moderate-to-severe acute stress triggers the release of CRF from the hypothalamus, which modifies gut activity through the fibers of the autonomic nervous system.

The Trier Social Stress Test is a reliable method of inducing stress in a laboratory, but it’s sometimes criticized because it doesn’t reflect the diversity of tense and trying situations that people encounter in everyday life. With this in mind, researchers have assessed the catecholamine response to stress in more naturalistic situations—academic exams, a visit to the dentist’s office, even skydiving. Specific to sports, a slew of investigations have evaluated stress responses to real-life competition. Take for example a study that contrasted the stress responses of elite German tennis players under practice and tournament conditions; urine epinephrine (a.k.a. adrenaline) levels were about twice as high two hours before a tournament than in practice.40

Despite the fact that elevations in catecholamines are nearly ubiquitous in stressful situations, not all athletes experience nausea before competition. Although the stress response to athletic competition isn’t usually potent enough to induce nausea and vomiting in most athletes, there will always be exceptions, as in the cases of Philadelphia Eagles lineman Brandon Brooks and Celtics legend Bill Russell. And of course, the bigger the stage, the more likely an athlete will experience stress severe enough to trigger nauseousness. In Without Limits, the definitive running biopic about legendary runner Steve Prefontaine, there’s a notable scene in which Prefontaine pukes under the bleachers before the 3-mile race at the 1974 Hayward Field Restoration Meet, which was renamed the Prefontaine Classic after his tragic death. In the scene, Prefontaine laments that he doesn’t think he can hang with the likes of Frank Shorter and Gerry Lindgren anymore, even as the crowd chants his name. The scene perfectly sums up what countless athletes have felt in the moments leading up to their biggest competitions.

If you do happen to perpetually suffer from stress-induced nausea, you could consider implementing the following strategies to dial down the magnitude of catecholamine release in the hours leading up to competition:

Shun caffeine and other stimulants.

Shun caffeine and other stimulants.

Avoid dehydration and hypoglycemia by consuming adequate amounts of fluid and carbohydrate beforehand.

Avoid dehydration and hypoglycemia by consuming adequate amounts of fluid and carbohydrate beforehand.

Consult with a sports psychologist or other qualified mental health professional, as they can help you implement a variety of strategies—from breathing exercises to meditation to cognitive behavioral therapy—that could blunt catecholamine release prior to competition.

Consult with a sports psychologist or other qualified mental health professional, as they can help you implement a variety of strategies—from breathing exercises to meditation to cognitive behavioral therapy—that could blunt catecholamine release prior to competition.

I want to be clear that these strategies are based primarily on indirect evidence. Even so, there are probably minimal risks in trying them.

On a final note, one other gut function change that can stem from psychological stress is heightened gut permeability.41 While it’s transient and relatively harmless in many situations, gut leakiness may, in some cases, contribute to heat illness during and after prolonged exercise. Psychological stress increases gut leakiness via the actions of stress hormones like CRF as well as through its actions on various components of the immune system.42, 43 Much like with stress-induced nausea, it’s conceivable that interventions such as deep breathing and meditation could blunt the stress response to competition and subsequent onset of gut leakiness, though I’m not aware of research that’s documented those effects specifically.

ANXIETY

Up to this point, I haven’t made a distinction between stress and anxiety. I’m not a psychologist, so I won’t pretend that I’m qualified to speak on all the nuances that separate these two psychological phenomena. In general terms, however, mental health professionals tend to make some consistent distinctions between stress and anxiety. Definitions of stress and anxiety abound, but I’ll rely on the text that’s traditionally thought of as the Bible of psychiatry, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), currently in its 5th edition. According to the DSM-5, stress and anxiety are defined as follows:

Stress. “The pattern of specific and nonspecific responses a person makes to stimulus events that disturb his or her equilibrium and tax or exceed his or her ability to cope.”44

Anxiety. “The apprehensive anticipation of future danger or misfortune accompanied by a feeling of worry, distress, and/or somatic symptoms of tension. The focus of anticipated danger may be internal or external.”44

An important distinguishing feature of anxiety—based on the DSM-5 definition—is worry, and, notably, this worry stems from thoughts of future misfortune. The worries that accompany anxiety can come in many forms—vague and generalized in some cases, extremely specific in others.

For me, worries of being unable to speak effectively sometimes bounce around in my head during the hours preceding an important speaking engagement. When this anxiety is at its worst, my brain envisions and puts me through a series of disastrous possibilities, most of which are amalgamations of a past experience and what I know about the upcoming engagement (the room, the size of the crowd, etc.). In scientific studies, psychologists often refer to this transient anxiety as “state anxiety,” or anxiety in the moment. For other people, their worries are less specific, instead encompassing almost every aspect of their lives. This type of anxiety is often referred to as “trait anxiety,” which is the anxiety a person tends to experience generally and is thought to be more of a stable characteristic.

As you might expect, people’s state and trait anxieties usually correlate strongly with one another.45 Another way to say this is that people who live with loads of anxiety from day to day also tend to become more psychologically aroused and anxious when they’re in stressful situations. Even though they’re interrelated, there’s a reason for measuring both types of anxiety instead of just one or the other. If you asked me to complete two separate questionnaires regarding my state (in the moment) and trait (in general) anxiety on a Saturday afternoon in the summer, I’m likely to report low levels on both. However, if you ask me to complete these same two questionnaires 30 minutes before a job interview, you’re likely to see a divergence between the two, with scores on the state questionnaire spiking more so than scores on the trait questionnaire.

Beyond proximity to a stressful situation, other seemingly insignificant factors impact my state anxiety in performance situations. As an example, being stuck behind an elevated podium makes me feel surprisingly anxious in comparison to when I’m able to move freely in front of a crowd. I’m not sure why elevated podiums make me feel this way, but perhaps my brain interprets the situation akin to being prey that’s stuck in a highly visible spot and therefore vulnerable to encroaching predators. Another factor that impacts my anxiety is time of day, and for whatever reason, mornings are worse for me than any other time.

The reason for bringing attention to the distinction between state and trait anxiety is that it may have implications for gut function in athletes. You, for instance, might be like me in that you don’t have excessive general anxiety, but when competition time comes around, your nerves spike considerably. As a consequence, you might be more vulnerable to experiencing anxiety-associated gut problems around competition and might benefit from interventions that manage anxiety more acutely. Some of these interventions are listed here:

Avoid or limit caffeine and other stimulants on the day of competition.

Avoid or limit caffeine and other stimulants on the day of competition.

Avoid dehydration and hypoglycemia before competition by consuming adequate amounts of fluid and carbohydrate beforehand; eating huge amounts isn’t needed, but going into competition fasted is likely problematic for some athletes.

Avoid dehydration and hypoglycemia before competition by consuming adequate amounts of fluid and carbohydrate beforehand; eating huge amounts isn’t needed, but going into competition fasted is likely problematic for some athletes.

Distract yourself by talking to teammates or competitors at the event.

Distract yourself by talking to teammates or competitors at the event.

Breathe slowly and deeply for 5 minutes within 15–30 minutes of the start of competition.

Breathe slowly and deeply for 5 minutes within 15–30 minutes of the start of competition.

Try positive imagery or visualization.

Try positive imagery or visualization.

Practice positive self-talk to control negative thoughts; these statements should be realistic and believable (“I can relax myself” and “I am strong and capable”).

Practice positive self-talk to control negative thoughts; these statements should be realistic and believable (“I can relax myself” and “I am strong and capable”).

Do a quick progressive muscle relaxation exercise, such as contracting and slowly relaxing several muscle groups one by one.

Do a quick progressive muscle relaxation exercise, such as contracting and slowly relaxing several muscle groups one by one.

Obviously, implementing several of these strategies (particularly visualization and self-talk) is more nuanced than described above. If these practices are something you’d like to try, consider reaching out to a sports psychologist or coach who has experience with these techniques. Likewise, there are several good books that detail how to implement these sorts of strategies in sporting situations, including The Champion’s Mind by Jim Afremow and How Champions Think by Bob Rotella.

ANXIETY AND GUT FUNCTION

When it comes to anxiety’s effects on gut function, it can be challenging to distinguish them from the effects of psychological stress. This is partly because as the perceptions of one go up, so do the perceptions of the other. Obviously, some people cope better with stress than others and may not experience as much anxiety when stressed, but in general, self-reported stress and anxiety levels typically correlate pretty strongly with one another.

Even with these challenges in teasing out the effects of anxiety and stress on gut function, there is a small body of research that seemingly confirms that inducing anxiety is sufficient to cause some of the aforementioned gastrointestinal changes. In one notable example, volunteers underwent a series of stomach function evaluations after being put through a standardized 10-minute anxiety induction procedure.46 Specifically, volunteers wrote about events from their pasts that would make them anxious if they recalled them, which were then recorded and played back to them while they sat in a darkened room. To further spark feelings of anxiety, fearful facial expressions were projected in front of the volunteers on a screen. The researchers measured gastric pressures and volumes using an inflatable bag inserted through the mouth into the stomach. In comparison to looking at neutral facial expressions and listening to a neutral personal story, the anxiety-inducing procedure led participants to report discomfort at lower gastric volumes (489 milliliters versus 630). This means they were less able to tolerate stuff in their stomachs, and for an athlete this would potentially equate to more fullness and discomfort when eating before and during competition. Indeed, in another part of the study, the volunteers consumed a liquid meal during the 10-minute anxiety procedure, and in comparison to the neutral condition, listening to anxiety-provoking stories and looking at fearful faces aggravated the severity of fullness and bloating by roughly 25–45 percent.

It’s interesting to note that a similar experiment from the same group of researchers failed to find that this type of anxiety-provoking experience impacts colorectal function.47 Still, other studies consistently show that psychological stress intensifies colonic motor activity, not to mention the innumerable anecdotes that abound of people losing control of their bowels during war, high-level sporting competition, and other extremely stressful situations. In the end, whether anxiety impacts the functioning of your colon may come down to what it is that’s inducing the anxiety and whether the anxiety borders on fear. Sitting in a lab while reflecting on a distressful event from the past, for example, may simply not be potent enough to impact colon function, whereas being faced with possible death or thinking about playing in front of sixty thousand screaming fans is enough to do the trick.