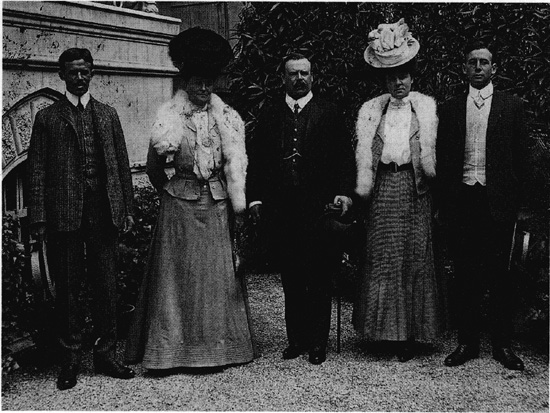

BY THE BEGINNING of 1902 Ward was nearly forty-six. He was a man of substance, carrying more weight than at any other time in his life. The picture of him opening the Dunedin Supreme Court building in June is of a sleek, portly man, slightly shorter than those around him, with a short neck and double chin touching the stiff wings of his collar.1 He had begun to wax the ends of his now famous, glossy moustache. His hair was receding a little at the temples and Seddon noted later in the year that Ward was showing some grey.2 However, he outsmarted most of the company he mixed in. At the court opening he wore a top hat and cape; his shoes were shiny black and spats are just visible. A substantial gold chain decorated his waistcoat. The cartoonist David Low was to write many years later that Ward ‘always dressed as though he had a lunch engagement at Downing Street’.3 He looked successful, authoritative, at ease with the world.

Domestically, Ward’s life was secure and happy. Theresa had had an uncomfortable pregnancy during 1900. She was carrying their last child, Awarua Patrick Joseph George (Pat), who was born on 14 January 1901. It was noticeable that apart from an appearance at the laying of the foundation stone of the new railway offices in Featherstone Street,4 Theresa took little part in the royal tour. Her health remained slightly delicate for the rest of her life, necessitating frequent holidays to the efficacious hot pools of Rotorua. At thirty-five, Theresa was a handsome woman with a smooth complexion, always beautifully dressed and with a penchant for elaborate hats. Ward adored her. In her clipping book was pasted about this time some lines he had penned to Theresa Dorothy Ward.5 The lines are pure mush, inspired perhaps by an excess of sentimentality evoked in Ward by the royal tour.

To you it is the lot of a Beautiful Queen

Here on earth to show kindness

Even to be enjoyed by those around you

Right Royally have you shown

Such kind offices to us

All, long to be remembered through life.

Ward at the opening of the Supreme Court, Dunedin, 1902. Hocken Library.

Dearly have you endeared yourself.

On all occasions, which will

Rest in our hearts when far away;

Only to be forgotten when life’s game ends,

Take to yourself comfort in

Having a good loving Husband

Young, Dear and sterling in his qualities.

Which is the greatest blessing to possess

And be enjoyed in married life,

Rest happily in your Queenly duties

Devoted to, and loved by all around.6

The poem shows little sign of modesty on Ward’s part. He was now a knight of considerable self-importance who had come to expect deference from others. He bestowed favours on them with almost regal condescension. His Christmas card for 1901 was scattered far and wide across Southland, with sparser coverage elsewhere in the country. It attracted considerable interest.7 A picture of a ‘Maori belle’ in front of one of the royal tour arches adorned the cover. Page two had a picture of ‘our future King reviewing the New Zealand troops in Hagley Park’, with J. G. Ward in a prominent position, while on page three were pictures of Bluff, ‘the most southern municipality in the world’. Finally on page four were pictured the Imperial troops in The Crescent, Invercargill, with J. G. Ward & Co.’s offices in the background. Reticence had never been Ward’s most salient characteristic; by the early 1900s he could scarcely spell the word.

Ward was the Cabinet’s rising star. When McKenzie resigned in June 1900 the appointment of his protege, Thomas Duncan, an amiable mediocrity, only demonstrated the extent to which the Seddonian triumvirate of the nineties had passed. Seddon and Ward, Ward and Seddon now ran the Government; the others were mere cyphers. Since Ward was eleven years Seddon’s junior, it was not surprising that speculation developed about the possibility of the younger man taking over. At the end of 1899 Mark Cohen told Edward Tregear that he thought Ward could ‘go to the top’ before long.8 A few months later Waldegrave wrote to Reeves that in his opinion Ward was shaping remarkably well. ‘If he only keeps as he is going he has a career. Adversity has I think broadened his views and strengthened his character. At all events he is the Rising Sun.’9

When Seddon’s health first began causing concern during the late autumn of 1900 the conjecture intensified. The News carried a letter suggesting that Seddon should go to London as Agent-General, allowing Ward, who was described as ‘far and away the most able and fitted for the position’, to take over as Prime Minister.10 When Ward acted as Prime Minister while Seddon was in Australia early in 1901 the guessing began again. The Wellington Evening Post, so hostile a few years before, seems to have succumbed to the rarified atmosphere of Awarua House. The paper kept circulating panegyrics about the Acting Prime Minister, talking of his ‘skill and assiduity as an administrator with a phenomenal capacity for despatching public business’. The paper noted that Ward’s industry seemed to be untiring. ‘At the present time he is practically running the entire Government of the country …. Mr Ward contrives somehow to transact the business of half a dozen men with smiling, unruffled countenance.’11

Ward’s first chance at the helm for any prolonged period of time came in 1902. Seddon was absent for six months at the coronation of King Edward VII. This time he did not call Parliament early and close it down during his absence as he had done in 1897. Initially he felt confident enough that Ward could handle things. It was election year, the session would be short; the Opposition was weak, still not having resolved its leadership difficulties. However, Seddon watched his locum’s management of Parliament from afar, and seems not to have liked what he saw. He sent copious advice. He could not understand why Ward rushed so early into presentation of a budget, noting that in his experience Members would pick away at the estimates for so long that there would be no time to get their minds back on to legislation before the session must end for the election. Nor did he approve of the magnitude of Ward’s public works programme. He protested privately to Ward that the increases in the estimates ‘appall me’, adding waspishly: ‘The Liberal Party has always been smashed up by weak finance.’12

Seddon had other gripes with Ward. At the end of the 1901 session Parliament had voted a sum of £30,000 annually as a subsidy for a permanent shipping service to South Africa and on to London. Tenders had been called and interest was quickly expressed by the Blue Star line. Ward, however, had other plans; he seems to have been working on his old friends at Nelson Brothers and delayed making a final decision until Seddon in a ‘private and confidential’ note to Ward told him: ‘I can hardly realise myself, getting the authority of Parliament last October and now at the end of June practically nothing has been done. If we do not get hauled over the coals we deserve it.’ Ward seemed unfazed by his chief‘s stricture, but in the end was unable to persuade his London friends to put in a tender. Blue Star won the contract.13

Others, too, had developed doubts about Ward’s tactical skills. Waldegrave had had cause to reflect: ‘Ward does not make much headway in the House. He has none of the foresight of RJS & I doubt very much whether he has a real sense of responsibility. They say he is making lots of money out of grain transactions. The danger with him is that he tries to outbid his chief & it is a risky game to play.’14

There were champions, however, none more vocal than the New Zealand Free Lance. Unlike Seddon, Ward was the great ‘pacificator’. Ward ‘has completely and convincingly demonstrated that he is a born leader of men, and that when King Richard chooses to lay down the sceptre he has a colleague thoroughly qualified to step into his place and both lead his party and rule the country with tact and judgement’. The weekly magazine praised Ward’s ‘studiously polite’ manner, his ‘happy disposition’, as well as his ‘bonhomie’, and noted that ‘the business of the House was despatched in a workmanlike style that beats all records’.15

On the surface the session of 1902 was uneventful. The Weekly Press reporter, ‘Pamela’, noted that under Ward’s management Parliament had a more social atmosphere. ‘The Acting Premier has, like Father O’Flynn, “a way wid him” with the ladies, and naturally endeavours to make politics attractive to them. So a new tea-room has been fitted up where our legislators may whisper sweet nothings or discuss the finances of the country with their feminine friends over excellent tea, thin brown bread and butter and biscuits. The latter, plain or fancy, are the furthest flight in afternoon tea dainties Bellamys can attain to.’ The Wards gave a parliamentary ‘At Home’ at Awarua House. Pamela concluded: ‘It was a highly successful function, admirably managed, and the Acting-Premier and Lady Ward accomplished with graceful ease what seemed almost the impossible task of entertaining six hundred guests in any private house.’16

While Wellington polite society watched the Wards the rest of the country were entertained by the almost constant antics of the Prime Minister abroad. On the way to South Africa he rescued some sailors in the Indian Ocean; in South Africa he travelled 3000 miles in little more than a week delivering several broadsides at the Boers. The Weekly Press claimed that Seddon, next to Lord Milner and Mr Chamberlain, ‘is the most popular man in South Africa’.17 In England Seddon partook of garden parties, dinners and even a ‘water party’ on the Upper Thames staged by the British Empire League. He visited his birthplace at St Helens in Lancashire, and contrived to appear almost daily in the British press. ‘Seddonism continues to be a prevalent cult in London’, wrote the Herald’s correspondent in July.18

When he arrived back in Auckland on 25 October 1902 Seddon quickly re-established his political ascendancy. A reporter caught the mood:

Sir Joseph Ward looked a very big man during the earlier part of last week, but his place in the public eye diminished bit by bit as the arrival of his chief drew nigh, and when the great man himself arrived on Saturday, though still plain Richard Seddon, Sir Joseph dropped almost out of sight, and the man who had been to London to see the new King fully occupied everyone’s attention. Mr Seddon completely overshadows all his colleagues, and, whatever we may think of his policy as a party man, all must admit that he has a wonderful knack of keeping himself before the public ….

Seddon lavishly praised those who had kept the government going in his absence. The reporter who covered the reception noted: ‘As [Seddon] said this he glanced with fatherly approval first on Sir Joseph Ward and then on the Hon. J. McGowan, who both seemed to be as pleased with this metaphorical pat on the head as children who had been given lolly-sticks for good behaviour in their mother’s absence.’19 Nevertheless, in reality, something akin to a joint Ministry had emerged. Waldegrave told Reeves that ‘our friend Sir Joseph now occupies in the Cabinet a position somewhat analogous to that of John McKenzie. That is to say, he will not be interfered with in his own Depts and assumes an attitude of complete equality with the Premier. They wont quarrel openly of course & they will work in face of a common danger, but they dont like one another & the womenkind dont make things easier.’20

Waldegrave’s comments almost certainly overstated the situation. There can be no doubt that Ward had established himself as the dominant minister of the Cabinet, and there had developed a degree of rivalry between his and the Prime Minister’s social sets. Whereas McKenzie was older than his chief, Ward’s relative youth marked him out as the obvious successor, and commentators enjoyed magnifying supposed rivalries between the old stallion and the younger. Throughout their period in harness together, Seddon needed Ward, and Ward served him faithfully, never losing a feeling of gratitude to his chief for his loyalty in troubled times.

Within days of Seddon’s return he was on the campaign trail and Ward had resumed normal battle stations in the South Island. Seddon had guessed right; little new legislation was able to emerge during the session,21 and even less was revealed about the Government’s intentions on the stump. The Liberals were beginning to lose a clear sense of direction. In the course of several weeks spent in Southland over Christmas and New Year 1901–2 it is possible to detect from Ward’s speeches occasional doubts about the Ministry’s capacity to hold its disparate legions of voters together. Questions from his audiences these days seemed subtly difficult.22 As general prosperity was unabated, political discussion turned more around sectional advantage. Farmers were becoming exclusive in pursuit of their interests. For many, the only mison d’etre for the state was to help those ‘on the land’. A political platform was drawn up amidst considerable debate at the Farmers’ Union conference in July 1902.23 Workers, too, were more exclusive with their concerns; urban overcrowding meant poor housing, pockets of unemployment and little job security in the rapidly growing towns and cities. In August the Workers’ Political Organisation met in Auckland and decided to stand two labour candidates in opposition to the Government.24 Divisive issues, too, kept resurfacing. Prohibition, local option on questions relating to liquor, and the introduction of Bible-teaching in schools were being discussed with some fervour at public meetings. The country it seemed, could now afford to indulge in envy, affluence and intolerance.

The politics of sectionalism was anathema to Ward. Till the end of his days he saw government as the helpmate of all sections, the plaything of none. ‘There is no class in the country that the Government has not helped by legislation to give them the opportunity by their own efforts of improving the opportunities that are available for them’, he told a meeting in Winton. To farmers who were beginning to see in unions fostered by Reeves in the nineties a possible challenge to their interests, Ward asserted that social legislation and compulsory arbitration of labour disputes were the means of avoiding the ‘savage and barbarous’ clashes between capital and labour that were features of the United States.25 A pragmatic state should maintain a harmonious society.

For the time being all sections retained their electoral faith in ‘King Richard’, as so many commentators now called him. Ward’s private secretary, Frank Hyde, had resigned earlier in the year and gone to Winton to edit the Winton Record, which became a broadsheet for the Liberal Party and Ward in particular. Hyde’s efforts helped Ward on 25 November 1902 to a victory by 2707 to 905 over a little-known opponent.26 Although Ward’s percentage of the Awarua poll dropped from 77.5 per cent to 75 per cent, his popularity seemed undiminished. A Times reporter at campaign headquarters in Winton on election night described the scene: ‘Sir Joseph Ward excels in occupying the waiting minutes of any company in which he may be, and where he is time rarely hangs heavy …. The crowd that collected to see the results as they were posted up had to wait at times …. As the results arrived they were immediately announced to the public by Sir Joseph Ward, who in some of the longer intervals of waiting kept the crowd amused by jocular remarks and a rather tall snake story which excited much merriment.’27 Ward’s neighbour, J. A. Hanan, consolidated his grip on Invercargill, and McNab held on to Mataura. In Wallace the faithful Gilfedder was replaced by a more able, younger, J. C. Thomson, who over time proved to be a loyal Liberal retainer. The Liberals lost some ground. But it was not the official Opposition that gained. Instead, independents, several of them pledged to the Government, won fourteen seats in a House that was now back to its earlier eighty members. One such was T. E. Taylor, who had been returned once more from Christchurch as an Independent Prohibition candidate, and who was to dog the Ministry’s heels for years to come.28

Seddon, Lord Plunket and Ward, 1904.

In the New Year the Wards decided to take a holiday in Australia around the time of the annual Postal Conference. On the afternoon of 16 February 1903, after welcoming Nellie Melba who had arrived in Bluff that morning, they set off for Hobart, Melbourne and Sydney.29 At each stop Ward met the state premier, praised New Zealand’s economic prospects, and in Sydney gave an audience a highly coloured version of his own earlier financial difficulties.30 In return, praise was usually heaped on New Zealand’s Liberal Government. At a dinner at the Australia Hotel in Sydney attended by the Australian Prime Minister, Sir Edmund Barton, and Ward’s friend, and later Prime Minister, George Reid, Ward was described to the gathering as the heir to Seddon.31

Back in New Zealand the political scene was described as being as ‘politically flat’ as it could be.32 Within the Liberal Party there was growing irritation at the composition of the Ministry. The impenetrable duo of Seddon and Ward stopped advancement on all personal and policy fronts. Having hinted at reconstruction of the Ministry before the election, and leaving McNab with the impression that he might get the nod,33 Seddon made no immediate changes. When William Walker resigned as Minister of Education in June 1903, the Prime Minister assumed the portfolio himself, and did no more than add two members of the Legislative Council to the Cabinet (Albert Pitt and Mahuta Te Wherowhero). Pitt became Attorney General. Speculation about further changes kept reaching the papers. First came the prediction that Duncan might be replaced as Minister of Lands.34 Then, in the hope of breaking up the leadership team, the story was circulated that Ward might resign and go to London as Agent-General. Ward hotly denied any such intention in September 1903. Tempers frayed in caucus, and party discipline, never a Liberal strong point, became even more exiguous. During the parliamentary session of 1903 Government supporters advanced a variety of nostrums and scenarios supposedly for the betterment of the country. Ward summed up the mood of the House neatly: ‘We have … land-nationalisers, financial reformers; we have … those who are anxious to reconstruct the Ministry, those who want to reconstruct the Legislative Council, those who want to reform everything, and some who want to annihilate everything …. Certainly a programme of extraordinary variety has been suggested.’35 In September 1903 several backbench Liberals, including Hanan, spoke in support of a want of confidence motion in the Ministry ‘as presently constituted’.36 But still noticing resulted; the Ministry’s critics could agree on nothing specific. ‘Reconstruction’ was everyone’s goal. To whose advantage could never be the subject of consensus.

When Seddon’s health broke down ‘completely’ in April 1904 due to the strain of work, speculation broke out again. Lord Ranfurly, the retiring Governor, was worried about him. Unless the Prime Minister took six months’ rest he would, ‘like the old warhorse answering the sound of the trumpet’, forget his ailments and his doctor’s orders and the strain would be too much.37 A group of younger, able MHRs, including McNab, J. A. Millar and George Fowlds, with only lukewarm support from Ward, who was never prepared to risk a break with his chief, began pressing Seddon to go to London.

The Prime Minister told his caucus in July that he had no intention of being ‘shunted’ to London and talked of introducing the concept of under-secretaryships to which some of the discontented might be appointed.38 They were not satisfied, and when Seddon tried to divide them up by making an offer of promotion only to McNab, they stuck together, making it clear that it was a new ministry they wanted, with a new approach to policy, especially to the thorny question of land tenure.39 As Dr W. A. Chapple, the handsome Wellington general practitioner who was one of the plotters, expressed it to Fowlds, ‘the present Ministry must not absorb the Reform Party. The Reform Party must absorb the Ministry or patiently wait till it can replace it.’40

Seddon himself kept the issue of his own intentions alive by introducing legislation to upgrade the Agent-Generalship to High Commissioner status with enhanced salary. Try as he did to convince his backbenchers that he was not interested in the position himself, delay in filling the office kept everyone guessing. P. J. O’Regan assumed Seddon was going; Waldegrave was equally certain that Seddon’s ‘grip on power is so intense that I doubt very much whether he will tear himself away’.41

The Cabinet, 1904. Ward is third from the left, next to Seddon.

In fact Seddon was in two minds. Occasionally he seems to have been genuinely interested in escape, but his wife had no yen for London. And the more he thought about it, the less he seemed, as Waldegrave had guessed, able to tear himself away from the political scene in Wellington. His own indecision paralysed the Government. ‘There is fearful discontent in the Government ranks’, Waldegrave told Reeves at the end of October 1904. ‘Seddon seems to have lost all initiative. He is always … putting everything off. The administration … is paralysed. The Government of Richard Seddon, by Richard Seddon for Richard Seddon about describes the situation. The main thing to remember is that while RS is here there is no room for anyone else & I see not the slightest prospect of there being a shuffle unless he shifts himself.’42 Ward simply carried on doing his own work. He listened to the schemers who would talk first of dislodging Seddon, and then, when that seemed impossible, began again to contemplate shifting Ward to London, the better to reconstruct the Ministry. Ward decided to sit tight. He was the only surviving member of Ballance’s Cabinet, besides Seddon. He was still only forty-eight. The prime ministership would have to be his one day.

As the Government drifted, press speculation continued. Inevitably Ward and Seddon were led into making occasional indiscreet utterances about each other to their visitors. These were flashed to other malcontents, and occasionally turned up in the press 43 Seddon in particular was moved to express the opinion privately that Ward would be unable to put together a credible ministry and would be unlikely to win the 1905 election.44 Any rift between the two, however, was never more than superficial; Seddon needed Ward just as Ward out of loyalty could not move against Seddon. The plotters and schemers grew frustrated, especially when Ward spent several weeks in Australia in March and April 1905, partly, one suspects, to dodge the intriguers. Chapple complained to Fowlds of ‘the doubting, shiftless, spineless mass represented by a monosyllable’.45 While the country was in no doubt about who would succeed Seddon, some of Ward’s colleagues clearly doubted whether he should; one or two hoped to keep him out.

Richard Seddon, December 1905. Schmidt Collection, Alexander Turnbull Library.

With an election approaching these differences had to be sorted out. It seems to have been James Coates, general manager of the National Bank, long a confidant of Seddon’s, who finally resolved the difficulties. He persuaded Seddon to stop thinking of London in the short term, and to elevate Reeves to the new position of High Commissioner on the understanding that he would step down if Seddon decided that he definitely wanted London 46 Once this had been agreed in June 1905 the intrigue subsided, the schemers deciding to wait until after the election before resuming their agitation. By the middle of the month Seddon and Ward were at work on election strategies. The Prime Minister’s health remained suspect, but he was ‘mentally as active as ever’ 47 When he arrived in Auckland on 22 June, his sixtieth birthday, he was given a warm welcome which was repeated at a special birthday party in the Wellington Town Hall a few days later.

Holding the Liberal Party together was no easy job. The land question strained party unity like no issue before it. For several years now the Government caucus had been wracked by tensions over the merits of the leasehold versus freehold forms of tenure, as well as debates over various forms of leasehold. The principal merit of leasehold lay in the fact that in theory, so long as enough new land became available, urban workers could get on to the land with little or no capital. As the Ministry sought out and purchased the dwindling number of estates with the potential for subdivision, some disciples of McKenzie saw the lease-in-perpetuity as a principle worthy of vigorous defence. When leaseholds began to come up for renewal in various parts of the country others in the Liberal caucus wanted rent revisions that took account of steadily rising land values. All leaseholders viewed the freehold option which was being exercised by a growing number of settlers as permanent alienation of a scarce resource. McNab, who was most vocal on land issues, was a leaseholder who wanted a much shorter period of tenure than had McKenzie, with the right to renew leases at an increased rental.

As the Ministry thrashed around in search of a land policy, they took the step in 1904 of refusing to allow the freehold option to settlers of the new subdivisions near the North Island Main Trunk line. In August 1904 W. F. Massey, the new Leader of the Opposition, decided to exploit the seeming confusion in Government circles. Seddon had to move fast. He set up a Royal Commission to study the various forms of land tenure. From the parliamentary galleries ‘Pamela’ noted that the Prime Minister ‘showed much of his old vigour, but it was quite evident the views he held were not all shared by the House, for interruptions were frequent, and not always in the best of temper’.48 Ward sat quietly at his desk as the six-day debate droned on; the land question offered no-win options, given the charged emotional atmosphere that debating it always seemed to produce. The Royal Commission was neatly balanced between freeholders and leaseholders. It incurred huge costs in the course of its work as it tripped around the country interviewing farmers and receiving deputations. Its 1600-page report produced on the eve of the 1905 election suggested a few procedural changes but was unable to come to any conclusion on the issue of tenure. Once more there was a lengthy parliamentary debate. Ward participated this time. He made a plea for calm, dispassionate and deliberate consideration of the tenure issue—which fell on deaf ears. He told the House that he favoured a range of tenure options being available to settlers. He was not opposed to the freehold; he owned some himself. But he warned that it should not be the only option open to settlers. So long as the leasehold remained an option small blocks of land would continue to find their way back into the hands of settlers with few means. It was the most cautious, and probably the most sensible contribution to the debate by any member.49

Despite much legislation being promised in the Speech from the Throne at the start of the 1905 session, only a few Acts were passed. An Old Age Pensions Bill raised the pension from 7s.6d to 10s. per week because, said Ward, the country could afford it.50 A teachers’ superannuation scheme with several similar features to that introduced earlier for railway workers was also introduced, to begin on 1 January 1906. Much of the rest of the session was taken up with private members’ bills introduced by single-issue enthusiasts on the Government’s side of the House. One that caused Ward some difficulties was the Bible Lessons in Public Schools Plebiscite Bill in the name of T. K. Sidey, MHR for Caversham. All the religious denominations in New Zealand, except the Catholics, were in favour of simple scripture lessons during school hours.51 Catholics lacked the numerical strength in New Zealand to gain state subsidies for a national system of Catholic education to be established, and preferred in the meantime to keep religious teaching by others out of state schools.52

As the country’s most politically influential Catholic, Ward came under heavy pressure from his co-religionists to stop Sidey’s Bill. Within days of the introduction of the Bill Ward was assuring Father Cleary, editor of the New Zealand Tablet, in a ‘private and confidential’ letter that it would be unlikely to get to a select committee; that if it did get that far, it would not emerge; and besides, if there ever was to be a referendum, he would ensure that the wording was such that the status quo was likely to prevail. It is clear from the letter that Ward felt himself under pressure from those who would make his religion an issue—both those who wished, as he said, to ‘rouse the sectarian cry’ against him, as well as from fellow Catholics who seemed to want him to die in a ditch for their cause. ‘I am pretty right in saying that 4/5ths of my constituents are Presbyterians … and … being a Catholic … it would not be difficult, if the cry were raised around my heels, to return an out-and-out Bible in Schools man for my seat. I think in the interests of our own people it is of far greater importance that I should be in than one of this kind’, he reminded Father Cleary.53 Archbishop Redwood readily accepted Ward’s stance on the issue. The heat went out of it as the election drew near and the ministers all resumed their normal election-time battle stations.

By November 1905 Seddon, who was greatly reduced in weight as a result of his riding, dieting and regular massages,54 was operating at full steam once more. He drew huge crowds as he worked his way round the country. Five thousand people greeted him in Auckland on 14 November 1905 where he talked about tariff reductions on workers’ clothing, his intention to build 800 workers’ dwellings in the Auckland area, and mused about the possibility of some universal form of workers’ superannuation.55 In Pukekohe, the heart of Massey’s electorate, the Prime Minister’s visit resembled a ‘triumphant procession’. A few days later the Times summed up his northern tour: ‘The Premier has been in his best “way back” form. He has overflowed with pleasantry. He has unburdened jealously guarded secrets and whispered momentous possibilities in the rustic ear, and generally speaking cut a cumbrous caper round the electorate.’56

Apart from a meeting at the Wellington Opera House early in November where he delighted his audience by telling an interjector to report to the Miramar Golf Course next morning for a beating,57 Ward spent most of the election looking after the South Island as usual. He had been home to Invercargill only twice since March, and had spent six weeks in Hobart, Melbourne, Adelaide and Sydney between March and early May following advice from his doctors to take a break.58 In the closing stages of the session came an unwelcome reminder of events long past. Victor Braund published a 200-page typescript entitled A Romance of Trade and Politics. As one of the Colonial Bank’s minor shareholders, Braund had become obsessed with Ward’s ever-upward progress since his collapse and had clearly spent much time sifting through public records seeking to besmirch Ward’s reputation. When completed, Braund offered Ward the opportunity to comment on the manuscript in a letter that Ward considered tantamount to blackmail. When no further comment was forthcoming, and all newspapers save only the Evening Post 2nd the Government’s own New Zealand Times, refused to advertise the manuscript’s existence, Braund went ahead and published it as a typescript. It caused discomfort to Ward, who, pour decourager les autres, began legal proceedings against the Post.59 James Coates reported to Reeves in November that Ward was ‘very well, but uneasy over raking up of the old Colonial Bank affairs’.60 There were no ripples electorally. Braund’s turgid prose and the price of 20 shillings a copy limited the manuscript’s circulation, and the editor of the Southland Times was almost certainly correct when he predicted that its vitriolic style was likely to rebound in Ward’s favour. The Otago Daily Times, which had earlier been one of Ward’s most hostile foes, added that the time was long past ‘for tolerating the insults [Ward] has endured at the hands of bitter opponents’.61

The Ward family at Awarua House, early 1906. Back: Eileen, Cyril, Vincent. Front: Theresa, Pat, Ward, Gladstone. Alexander Turnbull Library.

Awarua gave its member no electoral trouble. Ward’s nomination was contested by a Winton brick and tile maker, Henry Woodnorth, solely as a device to ensure that a licensing poll was held on the day of the general election. Ward campaigned in most parts of his electorate, however. For the first time he used a car, chauffered by twenty-one-year-old Cyril, who was now working for J. G. Ward and Co. in Invercargill. Ward was in the finest form as he defended the Ministry and its record in opening up the land. At Waikiwi in his most extravagant moment he claimed that ‘private wealth per individual’ in New Zealand was, at £381 per annum, ‘the highest of any people in the world’.62 The press too was at its most flattering. The News said of Ward’s Winton speech that it revealed ‘the mind of the statesman as distinguished from that of the mere politician’, adding that Ward’s chief asset was that he could make complexities simple for people to understand.63

The farewell to Ward as he set off to the Postal Congress in Rome, February 1906 — the last occasion he saw Seddon.

Ward romped home in his greatest victory, gaining 82.5 per cent of the Awarua vote. McNab, Hanan and Thomson held their seats, and across the country Seddon won his fifth and most spectacular success. The Ministry won another eleven seats, unseating such staunch Oppositionists as William Russell, Walter Buchanan and Ward’s old adversary, John Duthie.64 The new Governor, Lord Plunket, told the Colonial Office that Seddon’s victory was complete, and that his personal popularity seemed at its zenith.65 After fifteen years in power the Liberals were secure in office, the Prime Minister in undisputed control.

On 10 February 1906 Ward, Theresa, Eileen and secretary Ben Wilson sailed for Europe to attend the Postal Union Congress scheduled to take place in Rome in April. The trip had been a long time in the planning. The conference had first been mooted in 1903, then planned for the following year. Early in 1906 Cyril and Vincent departed for Europe by cargo ship sailing round Cape Horn. The rest of the party went via Australia where Ward spent several days on preparatory work for Seddon’s official visit planned for May. The Wards always enjoyed Australia. When they had been there the previous year the Sydney Catholic Press noted that Ward ‘so impress[ed] everyone in Australia that wherever he goes he becomes the lion of the day’.66 In Melbourne the Wards met the Prime Minister Alfred Deakin, talked trade in Adelaide with Premier Kingston, and were entertained at a cabinet luncheon in Perth. By the first week of April they were sightseeing in Florence, and were reunited with the boys in Rome. During the days before the congress Ward visited the Marconi wireless telegraphy station and was quickly impressed with the new inventions and their possible use in linking New Zealand to the rest of the world.

Sightseeing in southern Italy, April 1906.

In Rome, May 1906, on the way to meet the Pope.

On 28 April Ward spoke at the Postal Union Congress on the merits of universal penny postage, explaining how New Zealand’s experience had shown that new business generated by lower postal rates had more than compensated for the initial drop in revenue67 The conference listened politely. It resolved to give New Zealand its own seat on the Grand Committee separate from Australia, but lack of support from the major powers meant that universal penny postage made little progress. Ever the optimist, Ward wrote to Robert Anderson that penny postage ‘will come, but not yet’.68

There was much socialising. The Wards were entertained by the King and Queen of Italy, and Ward hosted a large dinner for conference delegates at which he announced that he was donating £200 to the Mt Vesuvius Sufferers’ Fund. The family was granted a private audience with Pope Pius X. Vincent recalled later that they all sat around the table, the Pope unable to speak any English nor the Wards any Italian. At last Vincent pulled out some photographs of the Pope which, with many smiles and chuckles, he signed for them. The touring party moved on to Naples, Ward usually with a pair of binoculars round his neck. The boys set off down the Rhine and then to Stuttgart in search of Grandma Gohl’s birthplace. The family met up again in Paris, but Ward soon announced that he was ‘fed up with foreigners as none of them understood what he was saying’. Armed with twenty-eight boxes of luggage they set off for London. At the sight of roast beef, bread, butter and tea, Ward regained his composure; he was returning to civilisation.

Ward decided that hotel accommodation in London was too expensive and rented a flat in Queen Anne’s Mansions by St James’s Park. He then went north for a few days to join his colleague George Fowlds, who was in Kilmarnock, Scotland, for his father’s hundredth birthday. Back in London Ward spent time at the Liberal Club where leading Liberals were again enjoying the spoils of office. Eighteen-year-old Vincent was beginning to develop a taste for politics and accompanied his father on most of these visits.

This picture of a happy family enjoying its first overseas trip together was shattered on 11 June by a cable from New Zealand. Vincent recalled a ring on the doorbell at 6 am and a telegraph boy handing him a telegram. He took it, went back to bed, and was later disturbed by his father coming into his room and picking up the sealed envelope. Seddon was dead.69