The presidential election of 1876 was deadlocked in the electoral college. The Republicans had failed to find anyone with even remotely Grant’s appeal and received many fewer votes, but there was an even tie in the college. This eventually led to a deal—the Wormley House pact of 1877—whereby the Republican went to the White House but the Federal Army was withdrawn from the South. The last Reconstruction governments there collapsed, to be replaced by white “Redeemers,” but the spirit of radicalism unleashed by the Civil War and its outcome had not yet been laid to rest.

The deal hatched by the Republicans and Democrats was not a pretty one. It sent the less popular candidate to the White House and allowed him to find jobs in Washington for a horde of displaced Southern Republicans. The press was full of reports of payoffs involving the award of railroad franchises. The new administration soon catered to bankers and bondholders by resuming specie payments. These developments confirmed the scathing assessments of the most dogmatic Marxists of the Socialist Party. The bosses were using the two main parties as blatant spoils machines, and in most areas they were oblivious to the plight of the growing working class. To the socialists, the need for a quite new party—a farmer-labor party—could not have been clearer. The Internationalists moved to form a Workers Party. Robin Archer has recently shed new light on why this possibility was nipped in the bud. He sees it as happening because of a combination of ferocious repression, Socialist sectarianism, and the reluctance of workers’ organizations to address political questions, since to do so would risk antagonizing the large number of religious workers with their ties to the existing party system.124

The existing party system was difficult to beat because it adjusted to the threat of third parties either by stealing their slogans or by ganging up against them—as the Republicans and Democrats did with their joint slate in Illinois in the 1880s. Successful labor leaders were wooed as candidates by the two established parties. But both parties took handouts from the robber barons, with state assemblies becoming the pawns of railway promoters awarding them large tracts of public land in return for kickbacks. The state authorities also frequently allowed the state militia to be used as strike breakers. Although striking workers sometimes enjoyed public support, the newspapers and middle class opinion easily turned against them.

However, it was an employers’ offensive and an across-the-board 10 percent cut in rail workers’ pay that detonated the Great Rail Strike of 1877. Many of the rail workers were Union Army veterans, and the rail companies sought to encourage their loyalty by issuing them uniforms and placing well-known generals on the board. But with this further pay cut such petty palliatives could no longer hold them in check. The Great Strike of 1877 has been described as “one of the bitterest explosions of class warfare in American history.”125 It reached inland to the great rail hubs and soon gripped the greater part of the North and West. Though it erupted three months after the ending of Reconstruction, the Great Strike did not come out of a blue sky. The employers had acted in a concerted fashion and counted on support from Washington, now that the political crisis had been resolved and the troops withdrawn from the South. The rail workers had much public sympathy, and their action encouraged others to down tools and take to the streets in urban areas.126 Workers in mines and steel plants joined in. The strike gathered momentum because some militia units were loath to threaten lives. One commander explained, “Meeting an enemy in the field of battle, you go there to kill … But here you have men with fathers and brothers and relatives mingled in the crowd of rioters. The sympathy of the people, of the troops, my own sympathy, was with the strikers proper. We all felt that these men were not receiving enough wages.”127

In St. Louis, the strike, orchestrated by the Workingmen’s Party, an offshoot of the International, had control of the city for several days. Burbank reports:

The British Consul in St. Louis noted an example of how society was being turned upside down: on a railroad in Ohio, the strikers “had taken the road into their own hands, running the trains and collecting the fares” and felt that they deserved praise because they turned over the proceeds to company officials. The consul commented stiffly that “it is … to be deplored that a large part of the public appear to regard such conduct as a legitimate mode of warfare.”128

The strikers produced their own newspaper, the St. Louis Times, which attacked the voice of the city’s leaders:

The St. Louis Times jeered at The Republican’s solemn warnings, quoting the phrase about the railroad men striking “at the very vitals of society”: on the contrary, said the Times, it was “the very vitals of society’ which were on strike, ‘and hungry vitals they are too!”129

African Americans played a prominent role in the St. Louis action, a fact harped on by municipal authorities and the local press in their attacks on the strike. A report of the general meeting convoked by the strike leadership noted: “The chairman introduced the Negro speaker, whose remarks were frequently applauded.”130 The strike leadership required the authorities to enact a series of radical measures, including restoration of wage cuts and the generalization of the eight-hour day, but were thwarted when a Committee of Public Safety set up by the leading men of the city raised a militia and sent it to crush the rebellion and end the strike. However, the black population of St. Louis remained a force to be reckoned with—in 1879 blacks fleeing Southern repression, the “Exodusters,” were able to shelter in St. Louis prior to leaving for Kansas.131

Just as the withdrawal of Federal troops abandoned the field to semiprivate white militia in the South, so the employers in the North were able to pay for thousands, sometimes tens of thousands, of National Guards, specially recruited “deputy marshals,” and Pinkerton men to break the strike, which had spread until it had national scope.132 One hundred strikers lost their lives in the course of the 1877 strike. The employers were also able to bring in black workers to take the place of strikers. The more far-seeing and enlightened labor organizers had urged that blacks be welcomed and organized, too, but it took time for formal recognition to be translated into practical action.133

The new president, Rutherford B. Hayes, noted in his diary that the 1877 strike had been suppressed “by force.” Grant, the man he replaced, was vacationing in Europe—he found these proceedings “a little queer.” During his own administration, Grant noted, the entire Democratic Party and “the morbidly honest and ‘reformatory’ portion of the Republicans had thought it ‘horrible’ to employ Federal troops ‘to protect the lives of negroes.’ Now, however, there is no hesitation about exhausting the whole power of the government to suppress a strike on the slightest intimation that danger threatened.”134

By the 1880s there were 30,000 Pinkerton men, making them a larger force than the Army of the Republic. The latter’s strength had dropped to less than 27,000, with those soldiers not in the West reduced to strikebreaking roles. By 1877 the Democrats were calling for Army strength to be further reduced to no more than 20,000. The robber barons of the North and West and the planters of the South had found brutally effective ways to cow the direct producers. Both distrusted the Army and both hated the Federal taxing power. The steep reductions in the Federal military establishment reflected both an economy drive and the conviction of some that an Army that stemmed from the Civil War and Reconstruction was not well adapted to enforcing labor discipline.

An unsavory alliance of politicos and robber barons had beaten the rail workers into submission, but this was just the start of two decades of large-scale clashes. From actions by the Illinois and Pennsylvania dockers, lumbermen, miners, and steelworkers of the 1880s to the Pullman and Homestead strikes of the 1890s, the United States was shaken by epic and desperate industrial struggles. These battles involved tens, sometimes hundreds, of thousands of workers and had no equal in Europe. In the great battles of the 1880s and 1890s, hundreds of strikers were killed, thousands imprisoned, and tens of thousands blacklisted. These grueling labor battles sometimes seemed like a civilian echo of the Civil War, with the strikers cast as copperheads, or even rebels, and the army, police, and deputy marshals as the loyalists. The Republicans, encouraged by Unionist veterans organizations like the GAR, sought to retain the support of their followers by voting pensions for veterans. Black veterans also qualified. Thanks to this, by 1914 the US provision for public pensions was larger than Germany’s, but it was destined steadily to diminish as the old soldiers died. This was a sectional welfare state; the Southern authorities did not have the resources to match it on behalf of Confederate veterans.135

Stephen Skowronek describes the closing decades of the nineteenth-century as the epoch of the “patchwork state” and emphasizes the role of labor struggles in shaping its peculiar formation.136 The antebellum regime had defended plantations without regulating them; the postbellum regime did similar service for the new corporations. It is sometimes believed that the Civil War, whatever else it did—or did not do—at least modernized and strengthened the US Federal state. But the authority of the state remained very uneven, the civilian administration was in hock to party placemen, and the legislatures were in league with the money power. These features had survived the war and been intensified by Reconstruction and its overturning. The frustration of “bourgeois” revolution brought no gain to Northern workers or Southern freedmen.

The double defeat of Reconstruction had suppressed black rights in the South and curtailed labor rights in the North. Jim Crow in the South and the widespread use of Pinkerton’s men and other goons in the North were both victories for privatized violence and a minimal view of the state. They were a defeat for the republican ideal of a unified and responsible federal authority. It was most particularly a defeat for Lincoln’s idea that the rule of law should be the “political religion” of all Americans.

There was orchestrated violence in the North, but it was put into the shade by Jim Crow. During the years 1884–1899, between 107 and 241 African Americans were murdered each year by lynch mobs, with total victims numbering more than 3,000. Lynchings were concentrated in the South and a great majority of the victims were black, but they were not unknown elsewhere and they sometimes targeted white labor organizers, Chinese, and Mexicans. Along the Mexican border dozens of Hispanics were lynched during these years. And there were also lynchings of whites in other parts of the Union, especially the “wild” West.137 The intensification of Jim Crow in the South was accompanied by the spread of onerous, if less extreme, practices of racial exclusion in other sections, affecting residence, employment, and education.138

The freed people of the South and the labor organizers of the North not only faced physical threats but also found their attempts to organize and negotiate assaulted in the name of the same conservative strain in free labor ideology—that which construed any regulation or combination as a violation of “freedom of contract.” The Republicans and Democrats deferred to this doctrine and the Supreme Court codified it. These rulings pulverized the workers and sharecroppers, leaving them to negotiate only as individuals.

Without a political order capable of regulating the employers, the case for a social democratic party was more difficult to make, and to some a syndicalist perspective seemed more realistic. Another obstacle to proposals for a labor party was the fact that the federal state was fiscally hamstrung, rendering impractical projects for a welfare state. The Union’s vast Civil War outlays had been met in part, as noted above, by the progressive income tax.139 However, in the early 1870s the income tax was dropped—and then declared unconstitutional by the Supreme Court. The Fourteenth Amendment had promised “all persons” the equal protection of the laws. Though this proved a dead letter so far as the freedmen were concerned, the corporations—who enjoyed the legal status of persons—successfully invoked it against measures for corporate taxation and regulation.

These and other reactionary developments might themselves have increased the willingness of the trade unions to back a labor party. Indeed, those trying to organize general or industrial unions aimed at the mass of workers realized that they needed the support of government. But Archer argues that many key craft leaders—especially Samuel Gompers—had greater industrial bargaining power and feared that their organizations might be put at risk if they teamed up with political adventurers.

Several key trade unions had been inspired by the agitation surrounding the IWA and Marx’s writings on the importance of self-organization by the workers. Several US unions were to describe themselves as International organizations—the International Longshoremen or International Garment Workers Union and so forth—an echo of the IWA. Sometimes the “International” was justified by its reference to organizing in Canada, but it had a resonance beyond this. If Marx’s followers—many of them German Americans—can take a share of the credit for the impetus given to trade union organization, they must also accept some of the blame for the failure of the US workers’ movement to develop a labor party and for the related tardy development and weakness of the US welfare state. Indeed, some blame the influence of Karl Marx for these failures.140

Yet Marx favored both trade unions and social democratic or socialist parties in the 1870s, as may readily be seen in the case of Germany. The German SPD was clearly linked to and supportive of organized labor, but its Erfurt program committed it to revolutionary and democratic objectives and to immediate reforms. It campaigned for votes for women and the defense of the German forests. It supported rights for homosexuals and an end to Germany’s imperial exploits in Africa, and it debated the “agrarian question.”141 The breadth of the SPD’s program did not, of course, wholly stem from Karl Marx but came also from several other currents, including the Lassalleans. Though Marx had tenaciously fought against what he saw as Lassalle’s misguided belief in the progressive character of the German state, he nevertheless went out of his way to cultivate Lassalle’s acquaintance, gently to warn him of his mistakes, and above all to remain in touch with the tens of thousands of German socialists who were influenced by him. Marx stressed the great potential and attractive power of the working class, but in his “Critique of the Gotha Programme” he combated the idea that labor was the only source of value, insisting that land (by which he meant nature) was a vital source of use values.142

The programmatic scope of the SPD is not the only evidence of the approach favored by Marx and Engels. The program of the French workers party was directly inspired by a conversation with Marx. Its very first clause declared, “the emancipation of the class of producers involves all mankind, without distinction of sex or race.”143 Its immediate program committed it to universal suffrage and equal pay for equal work. No doubt that economism still lurks in it, but in 1879 a platform like this was not such a bad starting point. The idea that trade unions and political organization are mutually exclusive put supposedly Marxian US Socialists and trade unionists at odds with their mentor.

The paternalist ethos of the early socialist movement rendered its commitment to equal rights for women ethereal and abstract. But as women were drawn into the labor movement in the 1880s, female activists challenged the idea that a woman’s place was in the home. While male labor organizers were prone to support the notion that the male worker should earn a “family wage,” the socialist organizations, especially those influenced by the German SPD, took a different stance: they urged that women would not be truly emancipated until they entered the world of paid labor on equal terms with men. August Bebel, one of the historic leaders of the SPD, wrote a book on the topic, Woman Under Socialism (1879), which was widely read in both German and English. Bebel urged that domestic labor should be lightened, and women’s employment promoted, by the provision of free communal child-care facilities and restaurants. Though they did not anticipate twentieth-century feminism and often romanticized patriarchal features of the family, the socialists of this era did pay some attention to the issue of gender equality.144 Female members of the Socialist Labor Party were able to offer a feminist interpretation of Bebel’s ideas and to use them to argue for the importance of organizing women workers. Given the employment of large numbers of women in new branches of the economy, socialist women became a significant force.

In 1887 Engels paid tribute to the giant strides being made by the American workers movement, embracing momentous class battles in Illinois and Pennsylvania, the spread of the Eight Hour Leagues, the growth of the Knights of Labor, the sacrifices that had established May 1 as International Labor Day, and the electoral achievements of the first state-level labor parties.145 But appreciative as he was, he insisted that the whole movement would lose its way unless it could develop a transformative program: “A new party must have a distinct platform,” one adapted to American conditions. Without this, any “new party would have but a rudimentary existence.” However, beyond saying that the kernel of this program would have to be public ownership of “land, railways, mines, machinery, etc.” he did not speculate as to what problems that program should address. Engels rebuked the doctrinaires of the heavily German American Socialist Labor Party for their hostility to unions and their failure to grapple with American reality. He urged them to “doff every remnant of their foreign garb,” “go to the Americans who are the vast majority” and “on all accounts learn English.”146

The advice Engels offered, though entirely justified, was also elementary and even simplistic. Programmatic thinking was not entirely lacking in the United States, but it was throttled by the given forms of the labor movement. In many trade unions there was a formal ban on any political discussion, on the grounds that it would prove divisive. The largest working-class organization, the Noble Order of the Knights of Labor, had a similar ban. The Knights of Labor only emerged from clandestinity in 1881 and never entirely shook off its roots as a secret society. Security threats distracted them from public debate of their objectives. Terence Powderley, the Knights’ leader, was intensely hostile to foreign-born doctrinaires and strove to exclude or neutralize them. The unions and the Knights made efforts to organize African American and female workers but had no discussion of how to campaign for respect for their rights.147

Engels’s text was most likely to be read by the members of the Socialist Labor Party, but he did not go far enough in pressing them to become relevant to US conditions. His insistence that the US labor party would have to commit itself to public ownership of the railways and steel was timely—and if it had been heeded by some progressive coalition it might have averted the disaster awaiting these industries in the mid to late twentieth century. His brief list should have included the banks, since they were critical to industry and agriculture. His call for the nationalization of land shortcircuited the tangled problems of the county’s three million farmers and four million tenants and laborers. By the time of the 1870 census there were 4.9 million wage earners, some of them white-collar, but the agricultural sector was still hugely important. The spread of the Farmers’ Alliance in the 1880s and 1890s showed the huge scope there was for mobilizing indebted farmers and rack-rented tenants or sharecroppers, both black and white. Engels endorsed the idea that a US labor party should aim to win a majority in Congress and elect its candidate to the White House, but without an appeal to farmers, tenants, and rural laborers—and many others besides—this was a pipe dream. While Marx and Engels were quite right to shun many of the “Sentimental reformers” with their patented cure-alls, some of these individuals focused on critical issues of taxation and banking, or security and democracy. The milieu of labor reformers had identified and skillfully exploited the issue of the eight-hour day, a programmatic demand that had a mobilizing and universalist impulse (though enforcement was often difficult under US conditions).

The London International had cordial relations with Richard Hinton, a labor reformer and organizer of the Washington, D.C., Section. When the German Marxist leader Sorge sought to bring this section under his control, the General Council in London declared that this was going too far and that the Washington Section should run its own affairs. This section refused to back Sorge’s expulsion of Section 12. The British-born Hinton was a former companion of John Brown’s and officer of the First Kansas Colored Regiment, and he was fascinated by Edward Kellogg’s plan for a network of public banks and Osborn Ward’s proposals for cooperative agriculture and industry. In late-nineteenth-century conditions the smallholder was on a hiding to nothing—cooperatives with some public support could have made a lot of sense. Hinton’s section included many civil servants, who would actually have to implement any massive program of nationalization. They were probably aware that the country only had 60,000 civil servants and any socialist plan must stimulate local publicly or socially owned enterprises and bottom-up initiatives.148 Hinton was later to be associated with Eugene Debs’s Socialist Party, as editor of its magazine.

In his survey Engels developed a very polite critique of the ideas of Henry George, even conceding that the land tax might have some role. Another radical taxation proposal that merited examination was Schuyler Colfax’s idea (mentioned above) of a levy on all shareholding capital.149 Finally, there was the issue of Lincoln’s very unfinished revolution in the American South. Prior to the triumph of the ultraracists in 1900 there were several movements which showed that white and black farmers and laborers could support the same goals; these included the Readjusters movement, which gained power in Virginia in the late 1870s, the Farmers’ Alliance, the “fusion” movement in North Carolina, and many branches of Populism. It is striking that these moments of interracial cooperation were targeted at the banks, the railroad corporations, and (in the case of Virginia) the large bondholders.150 The coal mines of Tennessee also witnessed trade union battles that brought together black and white workers opposed to their employers’ leasing of convict labor.151

The years 1886–96 witnessed the rise and fall of the People’s Party, mounting the most serious third party challenge to the post–Civil War US political regime. The Populist movement was born out of bitterness at the depressed condition of farming and at the venality of Wormley House politics. Farmers in all parts of the Union, but most particularly in the Midwest and South, called on the Federal and state authorities to come to the aid of farmers devastated by low prices, high freight rates and expensive credit. Among the demands launched by the movement were nationalization of the railroads, the coining of silver and the setting up of “sub-treasuries” at state and federal level which would serve as marketing boards for the main cash crops. The farmers’ produce would be held in public warehouses in each county; against this collateral they would be able to take out publicly-guaranteed, low interest loans. The People’s Party proved attractive enough to elect some Senators and Governors, and scores of state level legislators. It did particularly well in the South, especially where it reached tacit agreements with the Republican party to combine forces against the dominant Democrats.The party’s standard bearers were white but it received significant black support, partly thanks to tactical deals with the Republicans. The Democratic party responded with alarm and ferocity to Populist success, on the one hand adopting some of its more eye-catching proposals (e.g. monetizing silver in order to avoid “crucifying mankind on a cross of gold”) and on the other unleashing a campaign of physical intimidation against Southern Populists (in the Georgia campaign in 1892 fifteen men were killed because of their politics). Carl Degler suggests that the Democrat leaders saw the Populist challenge as a “second Reconstruction” and were determined to stamp it out.152 The defeat of the Southern Populists was accompanied by a further tightening of racial oppression and the consolidation of the Democrats as the unquestioned ruling party of the South. The Populists did try to reach out to the urban workers. They supported two policies cherished by organized labor—the eight hour agitation and opposition to the leasing of convicts to private employers. A group of Populists wanted Eugene Debs, the labor organizer, to become the party’s presidential candidate in the 1896 election but he declined. The Populists did not challenge the racial order and were easily deterred from coming to the defense of blacks. Their leaders sometimes couched their appeals in a stridently Protestant idiom that did not appeal to Catholics. The party’s most radical proposal was for the “sub-treasury” scheme but key leaders kept their distance from this. The rise and fall of the Populists showed that the idea of a Farmer-Labor party was not just an ideological figment but it also demonstrated the resilience of the reigning political regime.153

In private correspondence Engels had a poor view of the theoretical grasp of the American Marxists and socialists. However, Engels was hugely impressed by the anthropological studies of Lewis Henry Morgan and Marx took seriously Henry Carey’s economic writings. Within a little more or less than a decade of Engels’s death, three outstanding works appeared that would very likely have improved his view of critical thought in the United States: Louis Boudin, The Theoretical System of Karl Marx (1907); Thorsten Veblen, The Theory of Business Enterprise (1904); and W.E.B. Du Bois, The Souls of Black Folk (1903).

The eruption of titanic class struggles also had an impact on currents in US intellectual life far removed from Marxism. Eugene Debs’s American Railway Union (ARU) broke with the caution of craft unionism and tried to organize the entire railroad industry. In 1892 the ARU forced major concessions from the Northern Union railroad, and its membership grew to 150,000. However, when the ARU showed that it could paralyze one half of the entire rail network, the administration of Grover Cleveland stepped in to break the strike through injunctions and imprisonments. A conversation with an ARU picket had an electrifying impact on the philosopher John Dewey: “My nerves were more thrilled than they had been for years; I felt as if I had better resign my job teaching and follow him round till I got into life. One lost all sense of the right and wrong of things in admiration of his absolute, almost fanatic, sincerity and earnestness, and in admiration of the magnificent combination that was going on. Simply as an aesthetic matter, I don’t believe the world has been but few times such a spectacle of magnificent union of men about a common interest, as this strike evinces…The govt is evidently going to take a hand in and the men will be beaten almost to a certainty—but it’s a great thing and the beginning of greater.”154

Eugene Debs was arrested for defying the government injunction, and read Marx’s work in jail. Marx’s ideas were themselves beginning to influence the culture of US radicalism, just as they were also, in their turn, shaped by the American experience of robber baron capitalism and desperate class struggle. Marx’s dark vision clearly supplies the central themes of Jack London’s extraordinarily powerful novel The Iron Heel, a book read by millions in a large number of languages—and which many claimed had changed their lives. The history of the United States in the Gilded Age had resonated with such epic class struggles that they fleshed out the social imaginary of socialists and other radicals, not just in North America but also in Europe and far beyond—Latin America, Asia, and Africa. The New World had always tapped into European utopian longings, sometimes accompanied by dystopian fears. The United States of the great capitalist trusts and their Congressional marionettes offered an awesome spectacle—but so did the resistance of US workers and farmers. The international day of the working class, May 1, after all, memorializes US workers—the Haymarket martyrs of May 1886. So just as the US capitalist, with his top hat and cigar, typified the boss class, so the US workingman, with his shirt and jeans or overalls, became the image of the proletarian (and Lucy Parsons, Mother Jones, and “Rosie the Riveter” supplied his female counterpart). The set-piece battles in industrial America between the two sides were typically on a larger scale than European industrial disputes. There is, of course, irony in the fact that the iconic US worker was ultimately defeated or contained, while organized labor in Europe and the antipodes secured representation and even some social gains.

Albert Parsons, the Haymarket martyr, and his wife, Lucy Parsons, who did so much to defend the memory of her husband and his colleagues, had both participated in the Internationalist movement of the 1870s. They first met in Texas. Albert had volunteered for the Confederate army at the age of 13, but later came to apologize for this. Because of his military experience, he was made colonel of a militia regiment formed to defend Reconstruction. Lucy Parsons was a woman of mixed race (with indigenous, African and European forbears), who may have been born a slave. They moved to Chicago in the mid-1870s, where they were at first active as socialist agitators in the International Working People’s Association (IWPA), which saw itself first as a branch of the International and later were self-described anarchists. They were strongly committed to the idea that the workers needed to emancipate themselves. They were subsequently associated with a double attempt to radicalize the program and method of the trade unions. They insisted that the eight-hour day should mean “eight for ten,” that is, ten hours’ pay for eight hours’ work, or an eight-hour day with no loss of pay. This way of shaping the demand had not always been so sharply pursued before. They also propagated the idea that workers should support one another’s struggles with boycotts and sympathy strikes.

Albert Parsons was a gifted orator and journalist, but he also assisted in the formation of a workers’ militia that would protect political meetings and demonstrations. The Chicago businessmen had already formed their own militia, equipped with carbines and a Gatling gun. However, the famous Haymarket massacre involved neither of these formations. The workers’ rally was unarmed and unprotected. An individual, perhaps a provocateur, threw a bomb, and four policemen were killed in the resulting melee. Albert and Lucy, who were unarmed, had taken their children to the rally. The Chicago police responded to the bomb throwing by indiscriminate shooting, killing perhaps a dozen and may have caused some of their own casualties. The anarchist and socialist movement had rhetorically posed the question of revolutionary violence without clearly deciding and explaining the circumstances that might require and justify it.

The eight-hour movement in Chicago had huge support in May 1886, but that support was disoriented by the carefully orchestrated media hysteria claiming an anarchist terror plot. The subsequent trial of the supposed ringleaders of an armed uprising was a judicial lynching rather than a legal process—as the pardons later issued to those who had been imprisoned (rather than hanged) acknowledged and documented. The issuing of this pardon just eight years after the trial illustrates an interesting aspect of the Chicago anarchists: namely, that they did not abstain from electoral politics. Mayor Harrison testified in favor of Albert Parsons, and Parsons urged his followers to vote for Harrison—who lost in 1886 but was reelected in 1893. When Peter Altgelt, the Governor of Illinois, issued pardons to the surviving Haymarket leaders in 1892, he did not suffer electorally.155 Though generally scornful of politicians, Lucy Parsons expressed her high regard for Altgelt’s courage.

Lucy Parsons was a dedicated and accomplished orator, agitator, and organizer, roles that she sustained for half a century after her husband was hanged. She had a special gift for encapsulating the syndicalist worldview. From today’s perspective, her identity as a woman and a person of mixed ancestry—Mexican, white and black—makes her a symbol of multiculturalism. However, her own self-conception stressed her identity as a neo-abolitionist exposing “wage slavery.” In the 1890s she launched a journal called The Liberator, a deliberate echo of William Lloyd Garrison’s famous abolitionist magazine. She expressed her horror at Southern lynchings and other attacks on African Americans. But she believed that it was class, not color, that defined the exploited and the oppressed. She urged the Southern blacks to organize and resist without fully registering that white violence was designed to make this impossible. Her anarchist or syndicalist beliefs led her to warn Southern blacks that neither preachers nor politicians would help them. She became a member of Industrial Workers of the World, the syndicalist organization, at its founding conference in Chicago in 1905. For her, the redemptive power of “One Big Union” was needed to crush and scatter the bosses, whether the latter owned factories, railroads, or plantations.156

Another product of Reconstruction and the International milieu was Timothy Thomas Fortune, a New York journalist who had been born a slave in Florida and freed by the Emancipation Proclamation and who later served as an aide to his father, a Radical Republican. Fortune’s writings, especially White and Black: Land, Labor and Politics in the South (1884), analyzed the racial formation of class in the postbellum South. Fortune saw racial and class privilege as mutually supportive. His focus on the historic confrontation between “labor and capital” betrayed some Marxist influence, but he was also founder of the Afro-American League, one of the successors to the Black Convention Movement of 1830–70 and a precursor of the NAACP.157 In the 1890s he worked for Booker T. Washington and advocated measures favorable to black business and a black middle class.

Both color-blindness and conscious racism prevented US labor from taking up the cause of the victims of white oppression in the South. Employers were often able to exploit and foster racial antagonism. Booker T. Washington sometimes urged employers to take on black employees with the argument that they would be good workers who would spurn the troublemakers. Blinkered as they were, the more ideological wing of German American socialism never recanted their commitment to human unity. Even a writer as critical of the German American Marxists as Messer-Kruse concedes that they “never renounced their devotion to the principle of racial equality,”158 something which cannot be said of several traditions of Anglo-American socialism.159

If the nonappearance of a US labor party marked a critical defeat for Karl Marx, the failure of the Republican Party to emerge from Reconstruction and its sequel as a party of bourgeois rectitude and reform registered a spectacular defeat for Lincoln’s hopes for his party and country. After dominating Washington for half a century the Republicans were the party of cartels and corruption. The Democrats were also no slouches when it came to ingratiating themselves with Big Money or persecuting social reformers. Both parties failed US capitalism by offering neither honest stewardship nor the regulatory institutions that might have checked abuse and underpinned progressive development. Instead, as Matthew Josephson showed so vividly, venal “politicos” became the handmaidens of the new corporations and the enemies of social improvement.160 Moreover, no event so well exhibited the vices of the US political class as the Wormley House deal that ended Reconstruction in 1877. The violence of Southern whites was rewarded, the freedmen and women were abandoned, the wishes of the voters were flouted, and railroad contracts were forwarded or thwarted. The participants in these proceedings sought to camouflage their sordid character by claiming that “reform” would be promoted, but this had become a code word for spending cuts, not integrity and authority in Federal administration. The freed people were left on their own, while Republican placemen forced to flee the South were found jobs in the Treasury Department in Washington.161

But the real problem was that in each recession many banks failed and even in good times the service offered to farmers was miserably inadequate. The modest resources available to the Federal government were also a significant factor in the failure of Reconstruction, as we have seen. Abraham Lincoln gave considerable latitude to his treasury secretaries, but by inclination he favored private sector solutions and was wary of giving too much scope to publicly controlled entities. If the US postbellum record was much weaker than it should have been, the decisions taken—and not taken—by his administration help to explain this. However, it was the retreat from Reconstruction, the granting of virtual autonomy to Southern Dixiecrats, and the blunting of Federal powers by the Supreme Court that gave free rein to robber baron capitalism.

Marx and Engels themselves were often scornful of Republican leaders, including Lincoln, and generally distrusted the machinations of large states. But, with occasional misgivings, they had placed a wager that the Civil War would lead to slave emancipation, and that emancipation would in its turn pose the issue of votes for the freedmen. They further predicted more and larger labor struggles. Their predictions were borne out, although the new unions were eventually contained or defeated. The American Federation of Labor was founded, but it turned its back on the formation of a labor party. The example and watchwords of the Internationalists and of the Haymarket martyrs helped to encourage worker resistance in Shanghai, Petrograd, Calcutta, Havana, Turin, Barcelona, Berlin, Vienna, and Glasgow. In the years before the outbreak of the great slaughter in 1914, socialists, anarchists, and syndicalists worked to oppose imperial war, and to foster internationalism and class solidarity. And though they underestimated the power of nationalism and militarism, they were right about imperialism.

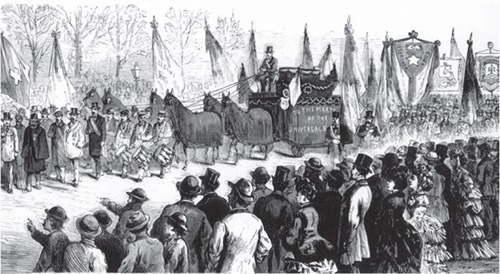

New York City IWA parade to commemorate martyrs of the Paris Commune, December 17, 1871 (original woodcut from Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, New York 1872).

It remains only to address a final problem. Karl Marx’s conception of history bequeathed a theoretical puzzle to later historical materialists, namely, what is the role of the individual in history? Such powerful writers and thinkers as Georgi Plekhanov, Isaac Deutscher, Jean-Paul Sartre, and Ernest Mandel debated the topic, often drawing attention to the fact that even deep-laid historical processes often depend on highly personal capacities and decisions. Considering the remarkable sequence of events I have surveyed here, it is clear that some individuals are so placed that they can influence the course of history. Lincoln did so with the Emancipation Proclamation. He thereby started a revolution, but he did not live to finish it. The freed people, the former abolitionists of whatever race, sex, or class had to contend with the consequences—angry white men in the South and greedy businessmen in the North. Through the IWA, Karl Marx had an impact on a generation of American workers and radicals, but despite heroic battles to do so, the IWA proved unable to build a political workers’ movement to compare with those in Europe and the antipodes.

This leads me to a final thought. What would have happened if Marx or Engels had themselves sailed from England to make their home in New York or Chicago? It would have provoked a sensation. Marx would have earned good fees as a lecturer, and his family, including his daughters and sons-in-law, would very likely have flourished. Engels was hugely invigorated by the trip he did make to New York and Boston in 1887, but he declined to give public lectures there, and he did not return.162

But the truly tantalizing issue is whether they would have been able to find a more promising path for the American left. Obviously, there is no real way of knowing. But if their conduct in Germany in 1848–9, or in the 1860s, is any guide, Marx and Engels would have strongly opposed any policy of subordinating the real movement to some socialist shibboleth. They might well have helped to consolidate the International’s achievements. They would very likely have favored opening the unions to the generality of workers and they would surely have given exceptional importance to curbing the freelance violence of the Southern “rifle clubs” and Northern company goons. Marx would have urged workers to develop their own organizations. But, just as he saw the importance of the slavery issue at the start of the Civil War, so he would surely have focused on “winning the battle of democracy,” securing the basic rights of the producers—including the freedmen—in all sections as preparation for an ensuing social revolution. Eschewing reactionary socialism or the counterfeit anti-imperialism of some Southern slaveholders, Marx and Engels would have insisted that only the socialization of the great cartels and financial groups could enable the producers and their social allies to confront the challenges of modern society and to aspire to a society in which the free development of each is the precondition for the free development of all.

1 August Nimtz, Marx and Engels: Their Contribution to the Democratic Breakthrough, Albany 2000.

2 Karl Marx, “American Soil and Communism,” in Karl Marx on America and the Civil War, Saul Padover, ed., New York 1971, pp. 3–6.

3 Karl Marx, “The American Budget and the Christian-German One,” in Karl Marx on America and the Civil War, pp. 9–12. For Marx’s emigration plans, see Padover’s Introduction.

4 These remarks are quoted in the introduction to an interesting selection of the articles, James Ledbetter’s Dispatches for the New York Tribune: Selected Journalism of Karl Marx, London 2006, p. 8.

5 British military expeditions that forced China to open its ports to British suppliers of the drug, which was produced in dismal circumstances by exploited Indians.

6 Eric Foner, The Fiery Trail: Abraham Lincoln and American Slavery, New York 2010.

7 Eric Foner, Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution, New York, 1989. For further discussion of whether these events amounted to a revolution, finished or otherwise, see Philip Shaw Paludan, “What Did the Winners Win?” in Writing the Civil War: the Quest to Understand, James McPherson and William Cooper, eds., Columbia, SC, 1998, pp. 174–200. However, Foner’s conclusions concerning the winners seem to me closer to the mark than Paludan’s, as I will explain below.

8 Jasper Ridely, Lord Palmerston, London 1970; see especially pp. 329–30, 346–7, 375–6, 403–4.

9 Karl Marx, “The American Question in England,” New York Daily Tribune, October 11, 1861.

10 Marx to Engels, July 1, 1861, from Karl Marx and Frederick Engels’s Collected Works, Volume 41, Marx and Engels 1860–64, London 1985, p. 114.

11 Karl Marx, “The North American Civil War,” Die Presse, October 25, 1861. This text is reproduced in full in the present volume. However there is no space here to print all Marx’s writings on the United States and the Civil War. These are to be found either in the Collected Works, or in the already-cited collection edited by Saul Padover, or in Karl Marx and Frederick Engels, The Civil War in the United States, third ed., New York 1961, pp. 57–71.

12 During this period the term filibuster meant an irregular military adventurer, particularly one from the United States who hoped to seize land abroad, especially in Latin America.

13 Marx, “The North American Civil War.” Marx’s stress on the centrality of political issues can be compared with the brilliant analysis offered by Barrington Moore Jr., in The Social Origins of Dictatorship and Democracy (New York 1969, pp. 111–58). Moore writes: “The fundamental issue became more and more whether the machinery of the Federal government should be used to support one society or the other” (p. 136). Although Moore’s analysis stands up very well, it does not sufficiently register three vital aspects to which I will be paying particular attention: the rise of nationalism, the role of African American resistance, and the awakening of the working classes. Directly or indirectly, Marx’s articles and letters do address these issues. For other accounts that were influenced by Marx, see Eric Foner, “The Causes of the American Civil War,” in Foner’s Politics and Ideology in the Age of the Civil War (Oxford 1980, pp. 15–33) and John Ashworth, Slavery, Capitalism and Politics in the Antebellum Republic, Vol. 2, The Coming of the Civil War, Cambridge 2007.

14 “The North American Civil War,” p. 71.

15 “The North American Civil War,” p. 71. Marx’s argument was on target. See Robert May, The Southern Dream of Caribbean Empire, London 2002.

16 Robin Einhorn, American Slavery, American Taxation, Berkeley 2008.

17 Lincoln, “The Perpetuation of Our Political Institutions,” in Abraham Lincoln: His Speeches and Writings, Roy Basler, ed., New York 1946, pp. 76–84, 81. See also Eric Foner, The Fiery Trial: Abraham Lincoln and American Slavery, New York 2010, pp. 26–30.

18 Leonard Richards, Gentlemen of Property and Standing: Anti-Abolition Mobs in Jacksonian America, New York 1971. See also David Grimstead, American Mobbing, 1828–61: Towards Civil War, Oxford 1998, pp. 11–2. Several of the riots were directed at the lecture tour of George Thompson, a British abolitionist.

19 “The Perpetuation of Our Political Institutions”, p. 83.

20 Lincoln, “The Sub-Treasury,” 26 December 1839, in Basler, Abraham Lincoln: His Speeches and Writings, pp. 90–112, 98.

21 “The War with Mexico,” in Basler, Abraham Lincoln: His Speeches and Writings, pp. 202–16.

22 Theodore Vincent, The Legacy of Vicente Guerrero, Gainesville 2001, pp. 195–9. For the significance of the black and mulatto population of Mexico, see Gonzalo Aguirre Beltrán, La población negra de México, 1519–1810, Mexico City 1946, pp. 223–45. For the racial rhetoric of “Anglo-Saxonism” at this time in the US see Roger Horsman, Race and Manifest Destiny: the Origins of American Racial Anglo-Saxonism, Cambridge, MA, 1981, pp. 249–71. Even opponents of the war sometimes appealed to the supposed superiority of the Anglo-Saxons, but Lincoln did not.

23 Basler, Abraham Lincoln: His Speeches and Writings, p. 209. Lincoln was at this time involved in a group that called itself the Young Indians. He was hugely impressed by a speech against the Mexican War delivered by Alexander Stephens of Georgia, another member of the group, in which he attacked hostilities that were “aggressive and degrading,” since they involved “waging a war against a neighboring people to compel them to sell their country.” Stephens insisted that facing such a prospect he would himself prefer to perish on “the funeral pyre of liberty” rather than sell “the land of my home.” Stephens, who remained friendly to Lincoln, was, of course, to become vice president of the Confederacy. The quoted excerpts are from Basler, p. 214.

24 See Charles Sellers, The Market Revolution: Jacksonian America, 1815–1846, Oxford 1991, pp. 125–30, 271–8, 396–427, and Melvyn Stokes and Stephen Conway, eds., The Market Revolution in America: Social, Political and Religious Expressions, Charlottesville 1996.

25 Gavin Wright, Slavery and American Economic Development, London 2004.

26 For example, those in Abraham Lincoln: His Speeches and Writings, Basler, pp. 278–9, 427, 477–8, and 513.

27 Engels to Marx, July 3, 1861, from Marx and Engels, The Civil War in the United States, p. 326.

28 Many historians reject out of hand, as Marx did, the idea that there was a Southern nationalism. Often they do so because they do not wish in any way to endorse the Confederacy or the later cult of Dixie. This is understandable, but wrong, as Drew Gilpin Faust has argued in an important study of the topic. Nationalism can be flawed and self-destructive, and it can change for better or worse. See Faust’s The Creation of Confederate Nationalism: Ideology and Identity in the Civil War South, Baton Rouge 1989. See also Manisha Sinha’s The Counter-Revolution of Slavery, Chapel Hill 2000, pp. 63–94. For the general argument, see Tom Nairn, Faces of Nationalism, London 1995.

29 The classic study is, of course, Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities, second ed., London 1993.

30 David Potter, The Impending Conflict, Don Fehrenbacker, ed., New York 1976; Eugene Genovese, The Political Economy of Slavery, New York 1967; Eric Foner, Free Soil, Free Labor, Free Men, New York 1970 and Foner, “Causes of the Civil War” in Politics and Ideology; John Ashworth, Slavery, Capitalism and Politics in the Antebellum Republic, 2 vols., Cambridge 1998 and 2007; Bruce Levine, Half Slave and Half Free: the Roots of Civil War, New York 1992.

31 Daniel Crofts, “And the War Came,” in A Companion to the Civil War and Reconstruction, Lacy Ford, ed., Oxford 2005, pp. 183–200; p. 197.

32 Lincoln’s steady focus on slavery after 1854 emerges clearly in Foner’s The Fiery Trial.

33 Bruce Levine, The Spirit of 1848: German Immigrants, Labor Conflict, and the Coming of the Civil War, Urbana, IL, 1992.

34 The overrepresentation of British immigrants among antislavery activists in the 1830s is noted in Richards, Gentlemen of Property and Standing.

35 Levine, The Spirit of 1848, p. 125. In later decades some German Americans did indeed soft-pedal women’s rights when seeking to recruit Irish American trade unionists, but while this should be duly noted, it is far from characterizing all German Americans, whether followers of Marx or not. For an interesting study that sometimes veers towards caricature, see Timothy Messer-Kruse, The Yankee International, 1848–76: Marxism and the American Reform Tradition, Chapel Hill 1998. This author has a justifiable pride in the native American radical tradition and some valid criticisms of some of the positions adopted by German American “Marxists,” but he is so obsessed with pitting the two ethnic political cultures against one another that he fails to notice how effectively they often combined, especially in the years 1850–70. See Paul Buhle, Marxism in the United States, New York 1983, for a more balanced assessment.

36 Nimtz, Marx and Engels, p. 170.

37 For the role of antislavery in swinging German Americans to the Republican Party in upstate New York, see Hendrik Booraem, The Formation of the Republican Party in New York: Politics and Conscience in the Antebellum North, New York 1983, pp. 204–5.

38 Kenneth Barkin, “Ordinary Germans, Slavery and the US Civil War,” Journal of African American History, March 2007, pp. 70–9.

39 Gary Gallagher, “Blueprint for Victory,” in Writing the Civil War, James McPherson and William Cooper, eds., Charlottesville 1998, pp. 60–79.

40 Mark Neeley, The Union Divided, Cambridge, MA, 2002, pp. 9–12.

41 Lincoln made a friendly response to an address delivered to him by a torchlight procession of German Americans at Cincinnati, Ohio, on February 12, 1861, in which he observes, “I agree with you that the workingmen are the basis of all governments, for the plain reason that they are the more numerous” but adds that “citizens of other callings than those of the mechanic” also warranted attention. See “Address to Germans at Cincinnati, 12 February 1861,” in Basler, Abraham Lincoln: His Speeches and Writings, pp. 572–3.

42 George Frederickson, “The Coming of the Lord: The Northern Protestant Clergy and the Civil War Crisis,” in Religion and the American Civil War, Randall Miller, Harry Stout, and Charles Reagan Wilson, eds., New York 1998, pp. 110–130.

43 Ralph Wooster, The Secession Conventions of the South, Princeton 1962, pp. 256–66.

44 Quoted by William Lee Miller in President Lincoln: the Duty of a Statesman, New York 2008, p. 106.

45 Abraham Lincoln, speech in Peoria (Illinois) on October 16, 1854. Available in Basler, Abraham Lincoln: His Speeches and Writings, pp. 283–325. The quote from the Declaration of Independence strikes a patriotic note, though some might conclude that the speech also queried the break of 1776, given the prominence of slavery in several North American slave colonies. No doubt Lincoln would have insisted that the objection was not available to George III and his governments, since they were massively implicated in slavery, and that at least the Founding Fathers were uneasy about the institution.

46 The phrase “And the war came” occurs in Lincoln’s second inaugural address (reprinted in this volume). It has been adopted for many valuable accounts, but its implicit denial of Northern agency fails to acknowledge the emergence of a new nationalism or to pinpoint the Union’s legitimacy deficit in 1861–2 and hence a vital factor impelling the president to remedy it. See Kenneth Stampp, And the War Came, Baton Rouge 1970; Daniel Crofts, “And the War Came,” in A Companion to the Civil War and Reconstruction, Lacy Ford, ed., pp. 183–200; James McPherson, “And the War Came,” in This Mighty Scourge: Perspectives on the Civil War, Oxford 2007, pp. 3–20, 17. The legitimacy deficit was the more damaging in that abolitionists and Radicals, who might have been the warmest supporters of the administration, felt it keenly. It was alleviated by the Emancipation Proclamation but not fully dispelled until 1865, as we will see

47 Sean Wilentz, The Rise of American Democracy, New York 2005, p. 783. Wilentz proceeds from these remarks to this conclusion: “The only just and legitimate way to settle the matter [the difference over slavery extension], Lincoln insisted…was through a deliberate democratic decision made by the citizenry” (p. 763). A riposte to this is suggested by Louis Menand’s observation: “The Civil War was a vindication, as Lincoln had hoped it would be, of the American experiment. Except for one thing, which is that people who live in democratic societies are not supposed to settle their disagreements by killing one another.” Louis Menand, The Metaphysical Club: A Story of Ideas in America, New York 2001, p. x. This important book, together with Drew Gilpin Faust’s The Republic of Suffering, New York 2007, prompts the thought that the massive bloodletting of the war weakened the justifications offered for it. Of course, those who went to war on both sides made poor guesses as to its duration, and this ignorance was itself a very significant cause of the war.

48 William Freehling, The South Vs. the South: How Anti-Confederate Southerners Shaped the Course of the Civil War, Oxford 2001, p. 39; and Michael Vorenberg, Final Freedom, Cambridge 2001, pp. 18–22.

49 Quoted in a perceptive study by Richard Franklin Bensel, Yankee Leviathan: the Origins of Central State Authority in America, 1859–1877, Cambridge 1990, p. 18. That rival expansionist impulses in both sections provoked sectional hostility was clear enough by the 1850s. See Michael Morrison, Slavery and the American West: the Eclipse of Manifest Destiny and the Coming of the Civil War, Chapel Hill 1997.

50 Bruce Levine, Confederate Emancipation: Southern Plans to Free and Arm Slaves During the Civil War, Oxford 2006.

51 “Abolitionist Demonstrations in North America,” Marx and Engels, The Civil War in the US, pp. 202–6.

52 “The Destruction of Slavery,” in Slaves No More!, Ira Berlin et al., Cambridge 1993, pp. 1–76; 36. The full text of Phelps’s proclamation is given in Freedom: a Documentary History of Emancipation, Ira Berlin et al., Cambridge 1985.

53 Kate Masur, “ ‘A Rare Phenomenon of Philological Vegetation’: the Word ‘Contraband’ and the Meanings of Emancipation in the United States,” Journal of American History, 93:4, March 2007, pp. 1050–84.

54 Marx and Engels, The Civil War in the US, p. 258.

55 Peter Kolchin, “Slavery and Freedom in the Civil War South,” in James McPherson and William Cooper, eds. Writing the Civil War, Charleston 1998, pp. 241–60.

56 James McPherson, “A. Lincoln, Commander in Chief,” in Our Lincoln, Eric Foner, ed., New York 2009, p. 33.

57 For the evolution of Unionist nationalism, see Bensel, Yankee Leviathan, pp. 18–47.

58 Dorothy Ross, “Lincoln and the Ethics of Emancipation: Universalism, Nationalism and Exceptionalism,” Journal of American History, 96: 2, September 2009, p. 346.

59 Louis Menand, The Metaphysical Club: A Story of Ideas in America, New York 2001, p. 45.

60 Menand, The Metaphysical Club, pp. 52–3.

61 Quoted Archer Jones, “Jomini and the Strategy of the American Civil War: a Reinterpretation,” Military Affairs, December 1970, pp. 127–31, p. 130.

62 See Steven Hahn, “Did We Miss the Greatest Rebellion in Modern History,” The Political Worlds of Slavery and Freedom, Cambridge, MA, 2009, pp. 55–114. See also James Oakes, Slavery and Freedom: an Interpretation of the Old South, New York 1990, pp. 185–92.

63 Letter to Gov. Johnson 26 March 1863, Abraham Lincoln, Speeches and Writings, pp. 694–5.

64 Mathew Clavin, Toussaint Louverture and the American Civil War: the Promise and the Peril of a Second Haitian Revolution, New York 2010, pp. 6–7.

65 Frederick Douglass, Life and Times of Frederick Douglas, quoted by James Oakes in The Radical and the Republican, New York 2007, p. 231.

66 Michael Vorenberg, Final Freedom: The Civil War, the Abolition of Slavery, and the Thirteenth Amendment, Cambridge 2001, 197–210.

67 Harold Holzer, “Picturing Freedom,” in The Emancipation Proclamation, Harold Holzer, E. G. Medford and Frank Williams, eds., Baton Rouge 2006, pp. 83–136.

68 Marx and Engels, The Civil War in the United States, p. 273.

69 “The Address,” Marx and Engels, The Civil War in the United States, pp. 260–1.

70 Ibid, p. 281. The meanings of the address are rarely addressed, so it is all the more regrettable to find it interpreted in a tendentious way, as it is in Timothy Messer-Kruse’s book The Yankee International, 1846–1876: Marxism and the American Reform Tradition, Chapel Hill 1998, pp. 54–6. This author notes Marx complaining at the “bother” of having to write something of such little importance as this address and claims that he only consented to do so because “[in] Marx’s view, slavery had to be destroyed in order to allow for the historical development of the white working class” (p. 54). This illogically insinuates that Marx was privileging the white workers by insisting that the more oppressed blacks should be freed first. In reality, Marx was rejecting the idea of a preordained sequence.

71 “The American Ambassador’s Reply,” in The Civil War in the United States, Marx and Engels, pp. 262–3.

72 Lincoln’s long attachment to the colonization idea is documented by Eric Foner in “Lincoln and Colonization,” in Our Lincoln: New Perspectives on Lincoln and His World, Eric Foner, ed., New York 2008, pp. 135–66.

73 Speech of September 18, 1858, taken from Harold Holzer’s The Lincoln-Douglas Debates, New York 1993, p. 189. This was not an offhand remark, but rather forms part of a careful introduction to his speech. However, on one point it jars with the positive terms he used more than a year before to refer to the enfranchisement of some blacks in the early United States. In a speech on June 26, 1857, on the Dred Scott ruling he cites the dissenting opinion by Judge Curtis, which had shown that some free blacks in five states in the 1780s did exercise the vote. While not advocating giving the vote to free blacks Lincoln seemed keen to stress that, contra Chief Justice Taney, some free blacks did have (voting) rights in the early republic.

74 Foner, Fiery Trial, p. 257.

75 See Foner’s essay in Our Lincoln, Eric Foner, ed., pp. 135–66. Manisha Sinha’s contribution to this volume also cites the African Americans’ influence in changing his mind on the question. See her “Allies for Emancipation: Lincoln and Black Abolitionists,” pp. 167–98. In this same volume James Oakes argues that the “unrequited labor” strand in Lincoln’s rejection of slavery became more marked in the late 1850s and the war years, in his essay “Natural Rights, Citizenship Rights, States’ Rights, and Black Rights: Another Look at Lincoln and Race,” pp. 109–34.

76 Allen Guelzo, Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation: the End of Slavery in America, New York 2004, p. 19.

77 Charles Vincent, Black Legislators in Louisiana During Reconstruction, Baton Rouge 1976, p. 22.

78 Oakes, The Radical and the Republican, pp. 238–43. Oakes explains that Douglass had declined an invitation from the president about a week after his meeting at the Oval Office in August 1864 on the grounds of a prior speaking engagement. Their third (very friendly) encounter was not until six months later. While both men were very busy the apparent lack of follow-through to the second meeting remains puzzling.

79 For social conditions in the Confederacy and of the reasons for its defeat, see James Roark, “Behind the Lines: Confederate Society and Economy,” in Writing the Civil War: the Quest to Understand, James McPherson and William Cooper, eds., Charleston 1998, pp. 201–27. Famine led to bread riots and contributed to the collapse in morale. See Paul Escott, After Secession: Jefferson Davis and the Failure of Confederate Nationalism, Baton Rouge 1978, pp. 137–8. See also Mary DeCredico, “The Confederate Home Front,” in Ford, A Companion to the Civil War and Reconstruction, pp. 258–76 and David Williams, Rich Man’s War, Athens GA 1998, pp. 98–103.

80 This address, like the first written by Marx, heaps praise on Lincoln as “a man neither to be browbeaten by adversity nor intoxicated by success; inflexibly pressing on to his great goal, never compromising it by blind haste; slowly maturing his steps, never retracing them; carried away by no surge of popular favor, disheartened by no slackening of the popular pulse” and so forth. “Address of the International Workingmen’s Association to President Johnson,” The Civil War in the United States, Marx and Engels, p. 358.

81 Marx and Engels, The Civil War in the United States, pp. 276–7.

82 Marx and Engels, The Civil War in the United States, p. 277.

83 I sketch British slave emancipation in The Overthrow of Colonial Slavery, London 1988, pp. 294–330. For a brilliant reading of the social meanings of British abolitionism, see David Brion Davis’s The Problem of Slavery in the Age of Revolution, New York 1975, and Slavery and Human Progress, New York 1984.

84 The classic study of the free labor doctrine is Eric Foner’s Free Soil, Free Labor, Free Men: The Ideology of the Republican Party Before the Civil War, New York 1970.

85 David Montgomery, Beyond Equality: Labor and the Radical Republicans, 1862–1872, New York 1967.

86 Karl Marx, “Introduction,” The First International and After, Political Writings Vol. 3, edited and introduced by David Fernbach, London 1974, p. 14.

87 As Carol Johnson points out, this leaves little room for long-term reformism. See Carol Johnson, “Commodity Fetishism and Working Class Politics,” New Left Review, 1:119 (1980).

88 Hal Draper, Karl Marx’s Theory of Revolution, Vol. III, The Dictatorship of the Proletariat, New York 1986, p. 273.

89 Raya Dunayevskaya, Marxism and Freedom, London 1971, pp. 81–91.

90 Levine, The Spirit of 1848, p. 145.

91 See, for example, Karl Marx, “Results of the Immediate Process of Production,” published as an appendix to Karl Marx, Capital, Vol. 1, [Penguin Marx Library], London 1976, p. 1033.

92 Hal Draper, The Dictatorship of the Proletariat, New York 1987, p. 15.

93 Engels to Joseph Wedemeyer, November 24, 1864, Marx and Engels, The Civil War in the United States.

94 Walter LaFeber, The New Empire: an Interpretation of American Expansion, Ithaca 1963, pp. 24–32.

95 Matthew Josephson, The Robber Barons, New York 1934.

96 Foner, Reconstruction, pp. 228–81, and William McKee Evans, Open Wound: the Long View of Race in America, Urbana 2009, pp. 147–74. See also David Roediger, How Race Survived US History, New York 2009.

97 Foner, Reconstruction, pp. 351–63.

98 Rebecca Scott, Degrees of Freedom: Louisiana and Cuba after Slavery, Cambridge, MA, 2005, pp. 43–5.

99 Steven Hahn, A Nation Under Our Feet: Black Political Struggles in the Rural South from Slavery to the Great Migration, Cambridge, MA, 2003, pp. 103–5.

100 The postbellum miseries of the freed people are trenchantly explored by Roger Ransom and Richard Sutch in One Kind of Freedom: the Economic Consequences of Emancipation, second ed., Cambridge 2001, especially pp. 244–53.

101 Foner, Reconstruction, p. 364.

102 Eric Foner, Reconstruction, pp. 439–40.

103 Eric Foner, Nothing But Freedom: Emancipation and its Legacy, Baton Rouge 1983, p. 85.

104 Steven Hahn, A Nation Under Our Feet, pp. 302–13.

105 The total cost of the war has been estimated at $6.5 billion by Claudia Goldin and Frank Lewis, prompting Phillip Paludan’s comment, “That amount would have allowed the government to purchase and free all the 4,000,000 slaves (at 1860 prices) give each family 40 acres and a mule and still have provided $3.5 billion as reparations to former slaves for a century of lost wages.” Paludan, “What Did the Winners Win?” in Writing the Civil War, McPherson and Cooper, p. 181.

106 W. Elliot Brownlow, Federal Taxation in America, Cambridge 1996, p. 26. Colfax was at this time in the Radical camp. Also see Vorenberg, Final Freedom, pp. 206–7.

107 Henry Carey, Letters to the Honorable Schuyler Colfax, Philadelphia 1865.

108 Richard Sylla, “Reversing Financial Reversals,” in Government and the American Economy, Price Fishback et al., Chicago 2007, pp. 115–47, p. 133.

109 Quoted in David Roediger and Philip Foner’s Our Own Time: A History of American Labor and the Working Day, London 1989, p. 85.

110 Quoted in Messer-Kruse’s Yankee International, p. 191.

111 “Address to the National Labour Union of the United States,” in Karl Marx on America and the Civil War, Saul K. Padover, ed., p. 144.

112 Ibid.

113 Paludan, What Did the Winners Win?” in Writing the Civil War, pp. 178, 183, 187.

114 Hahn, A Nation Under Our Feet, pp. 103–5.

115 See Angela Davis, Women, Race and Class, New York 1983, pp. 30–86.

116 Robert Dykstra shows that military service was a trump card in the debate over enfranchising black men in Iowa. See Robert Dykstra, Bright Radical Star: Black Freedom and White Supremacy on the Hawkeye Frontier, Cambridge, MA, 1993.

117 Women had been lauded for their contributions to the war as nurses and homemakers, but the passage from this to enfranchisement proved more difficult. See also Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, Correspondence, Writings, Speeches, Ellen Dubois, ed., New York 1981, pp. 92–112; 166–9. Dubois, in her editorial presentation, argues that Anthony and Cady Stanton were, in different ways, both trying to adapt the women’s movement to the need for wider alliances. While Anthony drew on “free labor” ideology to criticize women’s dependence, Stanton sketched the programmatic basis for an alliance between the women’s and labor movements.

118 “The Rights of Children,” Woodhull & Claflin’s Weekly, December 6, 1870.

119 “Man’s Rights, or How Would You Like It?” ibid., September 8, 1870.

120 “The International: Appeal of Section No. 12,” ibid., September 23, 1871.

121 Unfortunately this cordial tone was not maintained. Primed by the doctrinaire Internationalists, in a later letter Marx casually refers to Woodhull as “a banker’s woman, free lover and general humbug”; so far as sexual matters were concerned, Marx, the likely father of Frederick Demuth, was more deserving of the term “humbug” than Woodhull.

122 The classic study is Montgomery’s Beyond Equality; the IWA is discussed on pp. 414–21. But see also Herbert Gutman, Work, Culture and Society in Industrializing America, Oxford 1976, pp. 293–343, and Samuel Bernstein, The First International in America, New York 1962.

123 For a rounded assessment see Amanda Frisken, Victoria Woodhull’s Sexual Revolution, Philadelphia 2004.

124 Robin Archer, Why Is There No Labor Party in the United States?, Oxford 2008. This carefully researched and argued study is the most provocative work on its theme since Mike Davis’s Prisoners of the American Dream (London 1985) and extends the latter’s comparison of the US and Australia.

125 Eric Foner, Reconstruction, p. 383. For this momentous event see also Robert Bruce, 1877: Year of Violence, New York 1959, and Philip Foner, The Great Labor Uprising of 1877, New York 1977.

126 David Stowell, The Great Strike of 1877, Urbana, IL., 2006.

127 Quoted in John P. Lloyd’s “The Strike Wave of 1877,” in The Encyclopedia of Strikes in American History, Aaron Brenner, Benjamin Day and Immanuel Ness, eds., Armonk, NY, 2009, p. 183.

128 David Burbank, Reign of the Rabble: the St. Louis General Strike of 1877, New York 1966, p. 64.

129 Ibid., p. 25.

130 Ibid., p. 33.

131 For the role of African Americans in the strike and later see Bryan Jack, The St. Louis African American Community and the Exodusters, Columbia, MO, 2007, especially pp. 142–50.

132 Samuel Yellin, American Labor Struggles, 1877–1934, New York 1937.

133 Gutman, Work, Culture and Society, pp. 131–208.

134 Quoted in Foner’s Reconstruction, p. 586.

135 Theda Skocpol, Protecting Soldiers and Mothers: the Political Origins of Social Security, Cambridge, MA, 1992.

136 Stephen Skowronek, Building a New American State: the Expansion of National Administrative Capacities, Cambridge 1982, pp. 38–84.

137 Joel Williamson, The Crucible of Race: Black-White Relations in the American South Since Emancipation, Oxford 1984, pp. 117–8, 185–9; Ida B. Wells-Barnet, On Lynchings, with an introduction by Patricia Hill Collins, New York 2002 (first ed. 1892), pp. 201–2.

138 Desmond King and Stephen Tuck, “De-Centering the South: America’s Nationwide White Supremacist Order After Reconstruction,” Past and Present, February 2007, pp. 213–53.

139 W. Elliot Brownlee, Federal Taxation in America, Cambridge 1996, p. 26.

140 Messer-Kruse in Yankee International and Archer in Why Is There No Labor Party in the United States? come close to this but ultimately concede that on such questions there was a large gap between Marx and those in the US who regarded themselves as his followers. (These included Samuel Gompers.)

141 I have a very brief discussion of the programmatic ideas of the SPD in “Fin de Siècle: Socialism After the Crash,” New Left Review, 1:185, January/February 1991. For the evolution of the party’s positions on sexuality in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, see David Fernbach, “Biology and Gay Identity,” New Left Review, 1:228, 1998.

142 Marx and Engels, “Critique of the Gotha Programme,” in Marx, The First International and After, pp. 339–59.

143 “Introduction to the Program of the French Workers Party,” The First International and After, p. 376.

144 Mari Jo Buhle, Women and American Socialism, Urbana 1981, pp. 1–48.

145 See Frederick Engels, “Preface to the American Edition,” The Condition of the Working Class in England, New York 1887, reprinted in this volume.

146 Ibid., p. 14.

147 Davis, Prisoners of the American Dream, pp. 30–1.

148 Montgomery, Beyond Equality, pp. 387–477.

149 Brownlee, Federal Taxation, p. 26.

150 Evans, Open Wound, pp. 175–87.

151 Karen Shapiro, A New South Rebellion, 1871–1896, Chapel Hill 1998.

152 Carl Degler, The Other South: Southern Dissenters in the Nineteenth Century, Boston 1982, pp. 316–70.

153 See Lawrence Goodwyn, Democratic Promise: The Populist Movement in America, New York 1976; Michael Kazin, The Populist Persuasion, Ithaca 1998; Ernesto Laclau, On Populist Reason, London 2005, pp. 200–08; Robert McMath, American Populism: a Social History, 1877–98, London 1990.

154 Menand, The Metaphysical Club, p. 295; see also Archer, Why Is There No Labor Party in the United States?, pp. 112–42.

155 James Green, Death in the Haymarket: A Story of Chicago, the First Labor Movement and the Bombing that Divided America, New York 2006.

156 Lucy Parsons, Freedom Equality and Solidarity: Writings, and Speeches, 1878–1937, edited and introduced by Gale Ahrens, Chicago 2004.

157 T. Thomas Fortune, “Labor and Capital,” in Let Nobody Turn Us Around, Manning Marable and Leith Mullings, eds., pp. 143–6.

158 Messer-Kruse, Yankee International, p. 188.

159 Whatever their other failings, twentieth-century American Marx ists, white as well as black, were to make an outstanding contribution to the battle against white racism and for civil rights. No other political current has such an honorable and courageous record. It is to this tradition and a Marxist US New Left that we owe the term political correctness. Despite occasional excesses, PC has nevertheless proved to be a hugely progressive force, establishing a basic etiquette of respect and collaboration. Mocked though it sometimes is, its achievement is a noble one. This having been said, Marx—at least in his private correspondence—furnishes a field day for PC critics, though they should notice that his negative characterizations are bestowed impartially on Germans and French, Yankees and South Americans, blacks and Jews. Cherishing universalism, he is excessively hostile to any type of partiality.

160 Matthew Josephson, The Politicos, New York 1963.

161 Foner, Reconstruction, pp. 580–1; Josephson, Politicos, pp. 234–6.

162 Eleanor Marx and Edward Aveling also visited the US in 1887, and their combined lecture tour was very well received by the public. However, the visit was to be marred by controversies over the expenses claimed by Aveling. See Yvonne Kapp, Eleanor Marx, volume 2, London 1976, pp. 141–91.