All of the above stamps are on different mortaria, so that in total there are at least ten stamped by Anaus with the possibility of three more, whose stamps are too fragmentary or difficult for certain attribution to him. It is no surprise that these three would be from the very difficult die 1B. Of the ten undoubtedly stamped by Anaus, six are stamped with die 1A, three with die 1B and one with die C. In total at least twelve mortaria of his are now known from Wallsend making this site along with South Shields and Benwell his major market outside the Binchester/Catterick area.

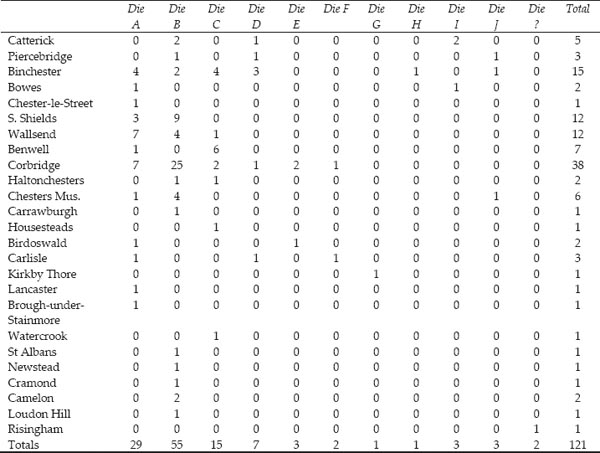

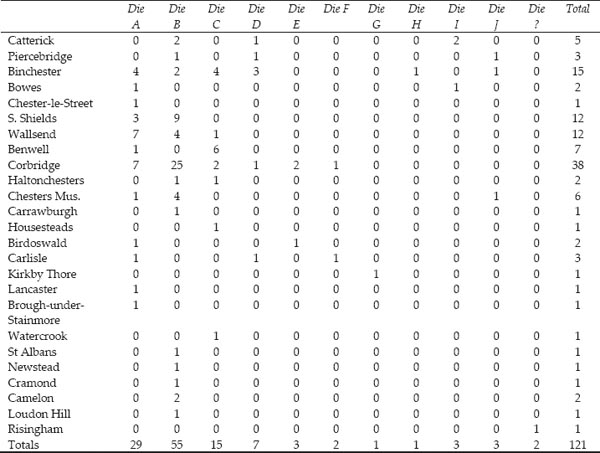

It has long been believed that Anaus had a workshop at Corbridge (Birley and Gillam 1948) and with good reason considering the number of his mortaria found there, but his distribution differs from that of other potters who can be attributed to Corbridge: not only is the number of his recorded mortaria far greater than for any other potter attributed to Corbridge, but far more of his work is found at sites outside Corbridge. There is also a markedly heavy distribution in the triangle bounded by Binchester, Bowes and Catterick – 25 compared with a total of three for seven other potters attributed to Corbridge (2 of Cudre- and 1 of Messorius Martius). His distribution leaves no reasonable doubt that he began his working life at Binchester and it seems likely that he moved to Corbridge later. His movements might well be expected to be related to the varying military occupation of these sites. The fort at Binchester was abandoned by AD125/130, and Fort 3 at Corbridge is believed to have been abandoned about the same time. If they were abandoned about the same time, he may even have had a third workshop, probably in the Catterick area where there was a thriving pottery industry.

Table 22.07: Distribution of Anaus stamps

Notes

‘Catterick’ has been used to cover all the Catterick sites (including Brompton-on-Swale), except Bainesse.

Stamps in Chesters Museum are not necessarily from Chesters itself, but from sites on the Clayton estates, on or in the vicinity of Hadrian’s Wall.

Dies have been given the letters used by Birley and Gillam 1948, with consecutive letters used for new dies.

One might expect the fabric of Anaus’s mortaria to fall into simple straightforward groups. The orangebrown fabric with very thick bluish-black core and cream slip like no. 7 is very typical and easy to recognise; it is particularly common at Corbridge, but the remaining fabrics are not as easily defined. Further work is needed on these to link them and individual dies with the different sources. Most of his mortaria in Scotland probably came from Corbridge and one might expect this to be true of his mortaria at South Shields and on Hadrian’s Wall, but an uncertain number of mortaria made by other potters, for example no. 25, at Wallsend can be attributed to potteries at Catterick.

One of his Binchester mortaria (die H) was found in an early Hadrianic context ending AD120/130 while one from South Shields is recorded from a late Hadrianic to early Antonine context (Bidwell and Speak 1994, 211, no. 7, die B). Five of his mortaria, all stamped with die B are recorded from sites in Scotland occupied in the Antonine period, indicating that this die was in use after AD140. The stamp from Risingham, now missing (die unknown) should also be Antonine. Stamps from die B are the most common at Corbridge (25 in 38). The distribution of die B suggests that it was mainly in use at Corbridge, though it would have been possible for mortaria from the Binchester/Catterick area to reach Scotland. The mortarium from Chester-le-Street should be later than AD158. A date of AD120–160 should cover the whole of his activity.

14. Area over Tower 2, unstratified, E02:11, WSP100 (44K). Wt:0.050kg. Incomplete rim-section of a very hard, apparently overfired mortarium fired to orange-brown near the surface, the rest reduced to dark grey with pale grey core; the slip is discoloured to brownish-buff. The fairly frequent inclusions are ill-sorted, though most are tiny to small-sized; they include quartz, black, brown and red-brown material. The trituration grit included quartz, brown sandstone and black material.

A fragmentary left-facing stamp survives, preserving the border and part of the F of a retrograde FECIT counterstamp used by G. Attius Marinus. This counterstamp and the namestamp which always accompanies it are essentially the same die-types which were used by G. Attius Marinus at Radlett in Hertfordshire before he opened his workshops in the Midlands. It is not possible to say how many actual dies were used throughout his midland career, but some of his stamps like this are from a die in the pristine condition of that first brought from Radlett, while many of his midland stamps are from a die or dies in which the borders especially are very degraded, never showing the fine detail visible in this example. This is a midland product and its optimum production period is, therefore, early in his midland period, within the range of AD100–120. Although none of his midland kilns have been found, there is evidence to suggest that he may have had a possibly short-lived workshop at Little Chester as well as one in the Mancetter-Hartshill potteries. Some mortaria were produced in orange-brown fabrics in the Mancetter-Hartshill potteries, especially in the early second century, but the production was minimal, whereas production in orange-brown fabrics was normal at Little Chester. This example might fit better with manufacture at Little Chester (for further details of the work of G. Attius Marinus see Hartley 1985, 126–9; Hartley 1999, 199, S21–2; and Hartley in Green (Little Chester), in preparation).

15. Building 10, contubernium 1/2, Period 2, E14:28, 1459, WSP242 (20K).

Wt:0.145kg. D:280mm. 14%. Softish, fine-textured, tancoloured fabric (Munsell 5YR 6/6 ‘reddish-yellow’), with few black ?slag, rare orange-brown material and quartz inclusions, small to tiny and random. The plentiful, smallish to medium-sized, trituration grit is very mixed in content, mostly quartz (transparent and pinkish), black slag and possibly other black material, quartz sandstone and redbrown sandstone. There are traces of red-brown slip on the upper surface of the flange, possibly ending in a line 4mm below the top of the bead. It is almost certainly a ‘Raetian’ slip and only one other possible example is known of its use on a mortarium of Austinus.

Complete impressions of this partially impressed, threeline stamp read as follows: the first line ΛVST, S reversed; second line NVS retrograde; the third line, retrograde FI followed by two uncertain letters, the second apparently a lambda L. The name was clearly Austinus and the following word is no doubt intended to be some version of FECIT. Stamps from the same die have now been recorded from Middlewich, Cheshire, Wallsend; Watercrook and Walton-le-Dale (4). Mortaria stamped with the remaining eleven dies of Austinus have now been recorded from the following sites: in Scotland (16–19), Bar Hill; Balmuildy (2–3); Birrens; Camelon (3–4); Carzield (2); Cramond (1–2); Durisdeer; Maryport; Milton; Newstead (2); Rough Castle and Strageath; in England (49), Ambleside; Birdoswald (3); Cardurnock (2); Carlisle (30); Chesters; Corbridge (4); Lancaster (2); Low Borrow Bridge; Maryport; Ribchester; Stanwix; Walton-le-dale and Watercrook.

The probability that Austinus began stamping mortaria at Wilderspool was discussed in Hartley and Webster 1973, 95–97. Recent discoveries show that many of the Wilderspool potters also had a workshop at Walton-le-Dale (information kindly supplied by Dr J. Evans), and the distribution of stamps from the die used on the Wallsend mortarium suggests that it was being used there. His major and somewhat later production, was undoubtedly at Carlisle, and he is likely to have also had a workshop in the Antonine Wall area. His mortaria at sites on Hadrian’s Wall and the Antonine Wall provide the key to his dating and his rim-profiles support a Hadrianic-Antonine date, perhaps within the period AD125–165, his Walton-le-Dale/Wilderspool production being c.AD125–145. The die represented here was in use early in his career, probably within the period AD125–140. The fabric of this example tends to fit better with production in the Walton-le-Dale/ Wilderspool potteries; in particular, it lacks the hardness usually associated with Carlisle fabrics.

16. Area over Building 10 and Alley 5, unstratified, F14:01, 1097, WSP243 (21K).

Wt:0.039kg. D: c.240mm. 6%. Fine-textured, pinkish-brown fabric (Munsell 2.5YR 6/6 ‘light red’) fabric with very thick yellowish-grey core (Munsell 2.5yr 7/2 ‘light grey’); very moderate, ill-sorted but mostly tiny inclusions including quartz, opaque grey pebbles, red-brown ?slag, opaque black and ?flint. No trituration grit survives. Slight traces of thin cream slip. The bead has been broken and turned outward to form the spout.

The fragmentary stamp, impressed along this collared mortarium reads C[……]; what may be the first and beginning of the second stroke of A can be seen following the C. No other stamp is known from the same die, but it is likely to be the work of a potter probably called Calles, who worked in Kent and whose mortaria match this in form and fabric. Calles frequently produced this unusual wall-sided type and stamped along the collar, both of which were unusual practices in Britain. The optimum date for both Calles and this example is AD150–180.

17. Building 16, floor, Period 4, N08:24, 2576, WSP256 (30K). Wt:0.119kg. D:310mm. 13%. Hard, fine-textured cream fabric probably with self-coloured slip; very moderate, random, ill-sorted quartz and orange-brown inclusions with random patches and streaks of pale orange-brown. No trituration survives.

The stamp, probably the right-facing one, reads CICVR and is from a die which gives CICVRFE in complete impressions for Cicur(o/us) fecit. Only one die-type is recorded for this potter. His work can be attributed to the Mancetter-Hartshill potteries. Twenty-one of his mortaria have now been recorded from Brough, Notts; Castor; Halton Chesters; Hartshill; High Cross; Leicester (2); Lincoln (2); Papcastle; Stanground South, Cambs; Twenty Foot, nr. March; Tiddington; Upton St Leonards, Gloucester; Wall; Wallsend (3); Wappenbury and Worcester. This distribution indicates that the bulk of his mortaria went to sites in the Midlands, only five have been found in the north, four from sites on Hadrian’s Wall including three from Wallsend, which has the largest number from any single site. The stamp from Halton Chesters was found in the packing underneath a floor of Period 1b. His activity is likely to have been within the period AD150–180, but his optimum date is AD150–170 because the practice of stamping could have ended around AD170+ in the Mancetter-Hartshill potteries.

18. Building 1, Period 2 demolition, Q04:02, 140, WSP262 (31K).

Wt:0.180kg. D:290mm. 21%. Two joining sherds in finetextured pale brown fabric (Munsell 5YR 8/4, ‘pink’), with slightly darker slip; moderate, ill-sorted quartz inclusions with some orange-brown and very rare black material. The few surviving trituration grits are orange-brown. The potter’s stamp, CICVR[..], with second C damaged and ghostly R, is from the same die as no. 17 above. This is the third mortarium of Cicur(o/us) recorded from Wallsend and is included in the above comments. AD150–170.

19. Chalet 9, Building W, late third/early fourth century, D13:71, 1612, WSP238.

Wt:0.225kg. D:340mm. 10%. Two joining fragments from a mortarium in self-coloured, dark cream fabric merging into a thick greyish-white core with frequent, ill-sorted inclusions, mostly quartz with rare orange-brown and black material. The trituration grit consists mostly of flint with a little quartz. The potter’s stamp reads from the outside DE[.]VM[.]S; DE is clearly impressed, but the remaining letters show up only on a rubbing. The name may be Decumus, but this reading cannot be regarded as certain until further stamps from the same die are found. The fabric cannot be sourced with certainty but on present knowledge the inclusions and the trituration grit would best fit the Verulamium region, though the inclusions are more ill-sorted than one would expect. The sandwich colours of the fabric would also be exceptional there, but it is difficult to find any other acceptable source for the flint trituration grit. The rim-profile and the distribution of the trituration grit would best fit a date within the period AD110–140. There is one other stamp, from Castleford (Hartley 2000, fig. 97, no. 26), which could have a similar reading, but that mortarium is probably a local product and the trituration grit and inclusions of the two mortaria are not sufficiently alike to attribute them to one source. Since the two stamps are from different dies they cannot yet be attributed to the same potter. There was also a potter called Devalus working in the Verulamium region AD60–90, but the rim-profiles recorded for him are very different, so it is not likely to be his work.

20. Area over Building 1, unstratified, L04:16, WSP97 (41K). Wt:0.045kg. An incomplete rim sherd in very hard, sandwich fabric, fired to buff-cream at the outside and underside surface (Munsell 7.5YR8/4), with core composed largely of pale brown buff (Munsell 7.5YR 7/6) and a thin range-brown inner core; the upper surface is fired to orange-brown. Cream slip. The moderate inclusions include tiny quartz and orange-brown material, with a few larger orange-brown. One quartz trituration grit survives. The fabric has some fine streaks in it similar to those in no. 36 below.

A fine border of diagonal bars survives plus the very ends of some letters. The stamp is almost certainly from the same die as no. 36, this example showing the lower border. Only further examples will permit identification.

21. Building Row 20, Building Q, late third/early fourth century, F11:11, WSP237 (46K).

Wt:0.522kg D:270mms 42%. This worn mortarium has been considerably affected by the conditions in which it has survived. There is a brown accretion over the whole of the surface and the fractures and the surface has suffered some slight exfoliation while the fabric itself appears to have been hardened and the colour slightly altered to a yellowish-cream which is untypical for the Mancetter-Hartshill potteries where it was made. There are moderate, tiny quartz and orange-brown inclusions with rare blackish material. The trituration grit is frequent, well-sorted and probably mostly red-brown though some may be blackish, with very rare quartz.

The incompletely impressed and very poorly preserved stamp reads [….]ΛSGVS and is from a die of Lugutasgus. Mortaria of this relatively uncommon potter are now known from Alcester; Catterick; Cirencester; Corbridge; Tiddington; Wallsend; and Wasperton. His work can be attributed to the Mancetter-Hartshill potteries c.AD135–165

22. Area over Alley 6, unstratified, 1648, WSP257 (32K). Wt:0.235kg D:360mm 15%. Fine-textured brownish-cream fabric, possibly with self-coloured slip; fairly frequent inclusions (tiny to small quartz, fewer ?slag and orangebrown and calcareous material), with fewer larger, mainly orange-brown. Two flint trituration grits survive.

The poorly impressed stamp is from the largest of the variants of a single basic die-type (Hull 1963, fig. 60, nos 6, 8 and 10) of Martinus 2, who worked at Colchester. See Hartley 1999 for further details of the die; this stamp is identical to S57, 60, 61 and 62. Martinus 2 had at least sixteen other die-types but this one with its variants is the commonest. His mortaria are now known from Braintree; Cambridge (2); Canterbury (2–3); Capel St Mary, Suffolk; Chelmsford; Colchester (up to 99); Corbridge (3–4); Gestingthorpe, Essex; Great Chesterford (3); North Ash, Kent; London/Southwark (6); Wallsend; Ware; York. Martinus 2 has the heaviest distribution outside Colchester of any of those Colchester potters who stamped names on their mortaria. He also has the heaviest distribution in north-eastern England of any of these potters and his absence from Scotland is noteworthy. The evidence as a whole suggests that his activity was within the period AD150–180.

23. Area over Via quintana, unstratified, M13:01, 1660 WSP251 (27K).

Wt:0.025kg D: c.270mms 9%. Flange fragment in finetextured, cream fabric with moderate, tiny to small inclusions, mainly pinkish quartz with some opaque orange-brown material. Probably had a self-coloured surface slip. The stamp, ]RRI is from the most commonly used die of Sarrius.

24. North-south drain east of Building 1, Period 2, Q05:03, 199, WSP263 (28K).

Wt:0.455kg D:290mm 25%. Fine-textured, cream fabric with moderate, almost to fairly frequent, tiny to small inclusions, pinkish and transparent quartz with some opaque orangebrown material. Some of the self-coloured surface slip still covers a few of the trituration grits. The trituration grit is red-brown with perhaps two quartz grits mixed in. Heavily worn. The partially impressed left-facing stamp is from a die which gives SARRI with leaf stamp between AR and a central stop before the second R.

The stamps on these two mortaria are from different dies. Both mortaria are from Sarrius’s workshop in the Mancetter-Hartshill potteries, which was active within the period AD135–165/70. He was the most prolific potter stamping mortaria in the second century, but he was most exceptional in having at least four workshops in the midlands, the north of England and Scotland. His Mancetter-Hartshill workshop was of major importance and the evidence suggests that it continued in production throughout his activity elsewhere at Rossington Bridge, near Doncaster (Buckland et al 2001), Bearsden on the Antonine Wall (Hartley 1984) and at an unlocated site in north-east England. Stamp no. 23 is from the die-type used at Mancetter, Rossington and Bearsden.

25. Area over Alley 5, unstratified, G14:01, WSP93 (35K). Wt:0.190kg D:280mm 18%.Orange-brown fabric (Munsell 5yr 6/6 ‘reddish-yellow’), fired to a paler colour at the surface, with traces of cream slip; moderate, ill-sorted inclusions, including quartz, quartz sandstone and orangebrown material. The trituration grit included quartz and red-brown ?sandstone.

The right-facing stamp is too battered to be readable but the dotted borders permit it to be identified as a stamp which reads SATVR on complete impressions, perhaps for Saturninus. Mortaria of this potter have now been recorded from Bainesse (4); Bowes; Catterick (5); Chesters; Corbridge; Piercebridge; and Wallsend. This distribution points to a workshop in the Catterick area. His rim-profiles would best fit a date within the period AD100–140. Saturninus 2 is not to be confused with Saturninus 1 who worked in the Verulamium region or Saturninus 3 who worked at Corbridge.

26. Area over Building 2 and Alley 1, post-Roman dereliction, M05:04, 34, WSP249; M05:04, 579; two joining sherds, Building A, north-south wall, late third/early fourth century, N05:10 (25K).

Wt:0.020kg (M05:04) Wt:0.224kg (N05:10) D:360mm 19%. Fine-textured, micaceous but slightly powdery fabric with some pink in the core and traces of a buff-cream slip; very moderate, ill-sorted and random orange-brown, quartz and slag inclusions, mostly tiny to small. A few quartz trituration grits survive.

The retrograde stamp (left-facing) is from the only known die of Valens; it has large herringbone borders above and below the name panel but all are part of one stamp. Other mortaria of his are known from Birdoswald Turret (Period 1B); Chesters (2); and Corbridge. Valens probably had his workshop at Corbridge although this example is not typical of Corbridge fabric. The find from Birdoswald Turret (Period 1B) suggests a date c.AD155–180 for his activity.

27. Surface over Building 1, Period 4 or later, N04:11, 178, WSP258 (2K).

Wt:0.060kg D: c.390mm 5%. Mortarium in greyish-cream fabric fired to greyish-buff at the surface; the frequent inclusions are mostly tiny and small, but not well-sorted quartz, with few red-brown and rare black ?slag fragments. No trituration grit survives.

The fragmentary stamp, [.]IICIT, is from the lower line of the only known die-type of Vediacus; parts of ] IA[ on the upper line also survive. Full impressions of this stamp read VIIDIACVS/IIICIT, A with diagonal dash, for ‘Vediacus fecit’. His mortaria are now known from Baldock (2); Benwell; Braughing (2); Godmanchester; Great Chesterford; Great Weldon; Higham Ferrars (3); Odell, Beds; Piddington (3); Rushden, Northants; Sandy, Beds. (2); Stanground South, Cambs; Stanwick, Northants; Stonea (2); Verulamium (4); Wallsend; Wellingborough; Wood Burcote Farm, near Towcester; and Wyboston, Beds. The only two recorded from the north are both from Hadrian’s Wall. The distribution of his work indicates activity in the Upper Nene Valley, probably in Northamptonshire and his rim-profiles fit a date within the period AD140–180, perhaps not earlier than AD150. For some interesting details of his work see Hartley 1994, 18–20.

28. Alley 10/Building 17, third century, E04:10, 417, WSP240. Wt:0.085kg. D:280mm 8%. Two sherds, not necessarily joining but certainly from the same mortarium in finetextured, micaceous, cream fabric with very smooth surface and slightly brownish-cream slip; few inclusions, most of them barely visible at X20 magnification, many probably quartz, some orange-brown with rare large orange-brown material and opaque white pebbles. Very few trituration grits survive, but they included quartz sandstone, orangebrown ?sandstone and quartz. Worn.

The broken stamp is from one of six die-types used by Vorolas; this one reads VOROLΛS retrograde when complete. Vorolas worked at South Carlton, Lincoln, where nearly 100 of his stamps have been found (Webster 1944). The fabric and profile of this example are entirely typical of his work. Other mortaria of his have now been found at Aldborough; Corbridge (2); Lincoln; Littleborough, Notts; Lutford Magna, Lincs; Templeborough; Wallsend and york. North-eastern England was, apart from the local area, the main market for potters working at South Carlton or in that vicinity, except for Crico whose work is found in Scotland. Their work is very homogeneous and there is no doubt of their Antonine date, certainly within the period AD140–180, though AD150–170 is probably the optimum date.

29. Tower 7, P04:05, 135, WSP260 (33K).

Wt:0.125kg D:280mm 13%.Self-coloured, fabric with finetextured, cream matrix (Munsell 10YR 8/4 ‘very pale brown’); fairly frequent and fairly well-sorted inclusions composed of quartz and orange-brown material with few black fragments. The surface is powdery but slightly abrasive due to the heavy tempering. The trituration grit included flint and quartz.

The partially impressed herringbone stamp is from the same die as Hull 1963, fig. 60, no 33. Colchester AD140–170.

30. Building 1, verandah, Period 3, L04:20, WSP174 (42K). Wt:0.040kg. D: c.280mm 6%. Self-coloured mortarium in fine-textured, yellowish-cream fabric (Munsell 10YR 8/4 ‘very pale brown’); only rare quartz and orange-brown inclusions, barely visible at × 20 magnification. The trituration grit included flint and quartz, mostly flint on fragment.

The left-facing stamp is a nearly complete impression from a herringbone die similar to Hull 1963, fig. 60, no. 29. Impressions of this stamp appear in slightly different lengths, suggesting that more than one die was used; they are so similar that they may have been made from the same matrix and they are always treated together. Colchester, AD140–170.

31. Area over Building 1, unstratified, Q05:02, WSP94 (43K). Wt:0.170kg D:320mm 13%. Self-coloured, yellowish-cream fabric (Munsell 10YR 7/6 ‘yellow’), with moderate to fairly frequent, random and very ill-sorted, flint and quartz inclusions. The trituration grit is composed of moderate to fairly frequent, vari-sized, flint and quartz, thinning out towards the bead, but with a few stragglers on top of the flange.

The herringbone stamp is the most commonly recorded of the Colchester herringbone stamps (Hull 1963, fig. 60, no. 30). AD140–170.

32. Via principalis, M08:09, WSP101 (45K).

Wt:0.130kg D:290mm 10%. Self-coloured, yellowish-cream fabric (Munsell 2.5Y 8/4 ‘yellow’), with thick pink-brown core (Munsell 5YR 7/6 ‘reddish-yellow’); moderate, random, very ill-sorted quartz with some opaque black material. The trituration grit is identical with that on no. 31 above except for the addition of a few soft, orange-brown fragments.

The edge of a right-facing stamp survives, which is too fragmentary for perfect identification, but it is almost certainly a herringbone stamp. This stamp is from a different vessel from all the other herringbone stamps recorded. Colchester, AD 140–170.

33. Building 1, north-south drain east of south wall, Period 2, Q05:03, 171, WSP261 (34K).

Wt:0.140kg. D: c.280mm. 7%. Self-coloured, fine-textured sandwich fabric, dark cream (Munsell 10YR 8/3 ‘very pale brown’) changing to pale orange-brown (Munsell 5YR 7/8 ‘reddish-yellow’), with dark cream core. The fairly frequent, fairly well-sorted, tiny inclusions are mostly quartz with some orange-brown and black material. The trituration is fairly frequent and well-sorted ending neatly about 23mm from the bottom of the bead; it is well-mixed and consists of flint, quartz, red-brown (?sandstone), slag and one soft, grey-white pellet, 14mm × 1.5mm. Worn.

The broken herringbone stamp has been found on seven mortaria in Scotland and on two other sites in England, Corbridge and a site near Sandwich, Kent. The fabric and trituration grit would be atypical for Colchester and a workshop in the Canterbury area is far more likely to be the source. AD140–170.

34. Area over Building 11 and Alley 6, unstratified, L15:01, 1338, WSP248 (24K).

Wt:0.058kg D:300mm 11%. Very hard, sandwich fabric, cream at surface, light brown outer core and deep cream inner core streaked with light brown; fabric very absorbent; smooth surface. The moderate to fairly frequent inclusions include random, large opaque white material which fractures easily (non-reactive) with some quartz, and rarer small orange-brown material. The few trituration grits surviving, include quartz, greyish quartz sandstone? and red-brown slag and possibly opaque white material. There are traces of a thin reddish-brown slip on top of the flange and at the bottom of the bead; this could be a ‘Raetian’ slip, but it is very rarely found on mortaria in the cream range and ‘Raetian’ mortaria were almost never stamped in Britain, so that this option is unlikely.

At least four herringbone stamps, some overlapping, are partially impressed across the flange. These appear to be from an unknown die. The absence of flint in the trituration or on the flange makes it fairly certain that this is not from any of the workshops in East Anglia, Kent or at Wiggonholt which regularly produced mortaria with herringbone stamps. Relatively dark slips on a cream fabric were common in the Lower Nene Valley, but herringbone stamps were rarely if ever used there. The source of this mortarium is therefore, uncertain, but the Nene Valley or Corbridge are possible sources. The rim-profile alone would tend to indicate a date in the early second century, but it is unlikely that herringbone stamps were being produced before about AD130 and most, if not all, were produced within the period AD140–170.

35. Area over Gate 3 and intervallum Road (road 6), unstratified, J16:01, WSP99 (39K).

Wt:0.040kg. A rim fragment, close to the spout, of a mortarium in hard, orange-brown fabric; probably selfcoloured. The fairly frequent inclusions are ill-sorted quartz; no trituration grit survives.

The fragmentary left-facing trademark stamp could well be from the same die as a stamp already recorded from Wallsend (Corder 1903, 46) and South Shields (Bidwell and Speak 1994, fig. 8.2, no. 3, found in the demolition of Periods 2–3). Unfortunately both of these stamps are also fragmentary and this example would be from the unrecorded part of this stamp. This example has the same very unusual raised band under the flange as the old find from Wallsend. All of the rim-profiles suggest a date within the period AD110–140. The distribution points to a workshop in north-east England.

36. Building 1, Period 2 demolition, M04:06, 475, WSP250 (26K).

Wt:0.162kg. D:250mm 17.5%. Brownish-pink fabric fired to cream near the outer surface, with very thin cream slip. The body is slightly distorted by the presence of a large (15mm × 6mm), fragment of ?slag, but the normal inclusions are almost invisible, mostly quartz and brown slag. Only one or two quartz trituration grits survive.

The broken stamp (right-facing) reads ]TI[ with an upper border of fine diagonal bars. The stamp on no. 20, a different vessel, is probably from the same die, but no other examples are known. The fabric and provenance point to manufacture in northern England; the rim-profile should fit a date within the period AD120–170, but the use of such fine borders would best fit an Antonine date. Borders such as these are rare outside the Mancetter-Hartshill potteries and further examples will enable identification.

37. Robber trench of south wall of Building 7, F11:07, WSP234 (47K).

Wt:0.138g D:280mm 12%. A heavily worn mortarium in granular greyish-cream fabric, with the surface of the flange somewhat exfoliated; abundant quartz inclusions with rare black and red-brown material. The trituration grit is worn away except for one flint and two quartz grits. There was a cream surface slip.

The incomplete and somewhat damaged stamp is from the same die as one from Lower Warbank, Keston in Kent (unpublished). The most complete version reads [..]OMX; the × will be a space-filler and it is not clear whether or not the stamp is retrograde. The fabric used can be attributed to a workshop in the important potteries south of Verulamium, mostly between Brockley Hill and Radlett, though the inclusions are not as well-sorted as commonly in their products. The optimum date for this mortarium is AD110–140.

38. Building 10, contubernium 3?, Period 2, F14:44, 1626, WSP244.

Wt:0.010kg Flange fragment in hard, fine-textured, orangebrown fabric (Munsell 2.5YR 6/8, ‘light red’), merging to a slightly greyer colour in core; with very moderate, random and ill-sorted inclusions, mostly quartz with some orangebrown and rare black. Cream slip.

The fragmentary stamp preserves part of a border and fragments of letters. It has not been possible to identify this stamp, but identification will be possible when further examples are found. North of England. Second century, probably before AD180.

39. Soil and rubble over end of Building 18, Period 3–4, H05:13, 817, WSP247 (23K).

Wt:0.045kg. D: c.250mm 7%. Orange-brown fabric (Munsell 2.5YR 6/8 ‘light red’) with thick, well-defined darker brown core (Munsell 2.5YR 5/4 ‘reddish-brown’); frequent tiny inclusions, mostly quartz with few larger quartz, black slag and red-brown material. Cream slip.

The stamp, probably a left-facing one, has been impressed along the flange. The stamp cannot be identified until further examples are found. This practice of stamping along flange or collar was never common in Britain, though examples are known from some workshops at some points in the first and second centuries. One or more of these workshops using generally similar fabric to this example, was in Kent in the second half of the second century, but only the discovery of further examples will enable identification of the source. The rim-profile together with this unusual stamping suggests an optimum date of AD150–180.

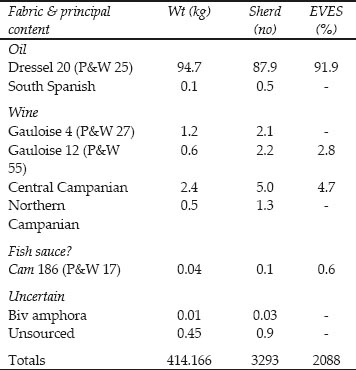

Table 22.08: Amphora from the excavations (all periods, including unstratified)

Key: P&W = Peacock and Williams 1986

The site produced 414kg of amphora from both stratified and unstratified contexts, making up 37.7% of all the pottery recovered from the site.

As usual on northern military sites, the assemblage is dominated by sherds from Dressel 20 amphorae, used to import olive oil for cooking and use in the bath-house. The wine amphorae, making up 10% of the assemblage by sherd count, came from both France and Italy. The flat-bottomed French amphorae were about equally split between those from southern France (Gauloise 4) and those from Normandy (Gauloise 12). They probably reached the fort during the second century and probably much of the third as well, as a Gauloise 4 amphora was recovered from Cistern 1, filled c.270 (Fig. 22.17, no. 114), but the quantities involved reflect the fact that much of the ration wine must have been supplied in barrels (Bidwell and Speak 1994, 216). From the middle of the third century Campanian wine began to be imported from the site, making up 3% by weight and 6% by sherd count. This is similar to the proportion found at South Shields, where the Italian amphorae make up 7% by weight (ibid., table 8.9, ‘black sand’ and ‘volcanic’).

Approximately 16% (by weight) of the stratified amphorae from the site was recovered from road surfaces, although this rises to about 28% when taking into account material from contexts unassigned to specific periods. Building 16 produced the largest quantity of amphorae of any individual building (18%), almost two-thirds of which came from the base of a single Dressel 20 in pit M08:43. The other building to produce a large quantity of amphora was the hospital (10% of the amphorae by weight); nearly 60% of this came from the infilling of the latrine and 25% from the open courtyard.

1. Building 1, verandah, Period 3, L04:20.

See also Fig. 22.17, no. 113.

2. Unstratified, E13:01.

3. Unstratified, H15:08.

4. Road 2, K05:07.

5. Alley 1, daub deposit, N05:23.

6. Unstratified, H15:09.

7. Unstratified, H12:29.

8. Unstratified, L05:03.

See also Fig. 22.17, no. 115

Gauloise 4: See Fig. 22.17, no. 114

Biv: see Fig. 22.17, no. 116

The excavations produced 14 stamps on Dressel 20 amphorae of which 9 were legible. Catalogue entries begin with the context number, followed by the small finds number and the record number. A transcription is given with a translation if necessary along with references to parallels from the principal texts.

1. ]RGI· ACRIGI Callender 18, Funari 22, Rodriguez 51. A parallel from Rome comes from a context dating 220–222. Source: La Catria 19, Guadalquivir Valley (Funari 1996, 21), (area of Building 2 and Alley 1, ploughsoil, L05:03, 590, WSP4).

2. DOMS DOMSCallender 552, Funari 170, Rodriguez 237. This has been found in a context in Rome dated 145–161. Source: Alcolea (Funari 1996, 54), (area of Building 11 and Alley 6, unstratified, M15:02, 1227, WSP5).

3. LI[ ]IM/ELIS·SI L. IUNI(US) MELISSI(US) Callender 879, Funari 136d, Rodriguez 189.

This stamp has been dated to AD 110–190. Source: Las Delicias (Funari 1996, 46 ), (rubble over east rampart and intervallum road, Q07:07, 2571, WSP9).

4. MSP MSP Callender 1180, Funari 211, Rodriguez 291. This stamp has been found in a contexts dated 145–161 and 179–180 in Rome. Source: Guadajoz (Funari 1996, 63), (area over Building 13, unstratified, N12:01, 1638, WSP6)

5. PMSA P. M(USSDII) S(EMPRONIANI) A Callender 1355b, Funari 155, Rodriguez 212.

Callender suggests that this stamp dates to the middle of the second century. (Funari 1996, 50), (Building 4, make up, Period 2, G04:07, 479, WSP3).

6. ]MR QMR Callender 1481, Funari 153, Rodriguez 209. The first character is faint but is almost certainly Q. This stamp has been found in contexts dated to 145–161 at Rome. (Funari 1996, 49), (area over Via principalis, unstratified, M08:01, 2494, WSP8).

7. ]MAN ROMAN Callender 1541, Funari 198, Rodriguez 279.

Second half of the first century to the first half of the second century. Source: Las Delicias (Funari 1996, 60) (north-south drain east of Building 1, Period 2, Q05:28, 330, WSP2).

8.

The closest parallel for this stamp is Callender 1696 which Callender suggests may date from the second half of the first century (Callender 1965, 256), (area over Building 13, unstratified, M12:01, 1696, WSP7).

9. ]LEHISAPI[..]NG

Table 22.09: Quantity of pottery from the excavations (kg).

| Stratified | Unstratified | |

| Samian | 18.990 | 31.817 |

| Mortaria | 34.499 | 43.418 |

| Amphorae | 166.838 | 247.328 |

| Fine wares | 9.625 | 14.455 |

| Coarse wares | 231.320 | 300.797 |

| Total | 461.272 | 637.815 |

The obscure characters between I and N are faint but may be a ligature of NE (area over Intervallum road (Road 4), unstratified, Q04:01, 10, WSP1).

Illegible or incomplete:

10.VVV [ (Building 8, room, 8, mid-third century?, E10:43, WSP169)

11. ] M [ (Building 1, demolition, Period 2 demolition, M04:06, 283, WSP10).

12. ] N (area over Building 9, unstratified, E13:01, WSP159).

13. ]. V. I [ (area over Building 7, unstratified, F11:01, WSP160).

14. Illegible (Cistern 2, upper fill, late third/early fourth century, H07:03, WSP161).

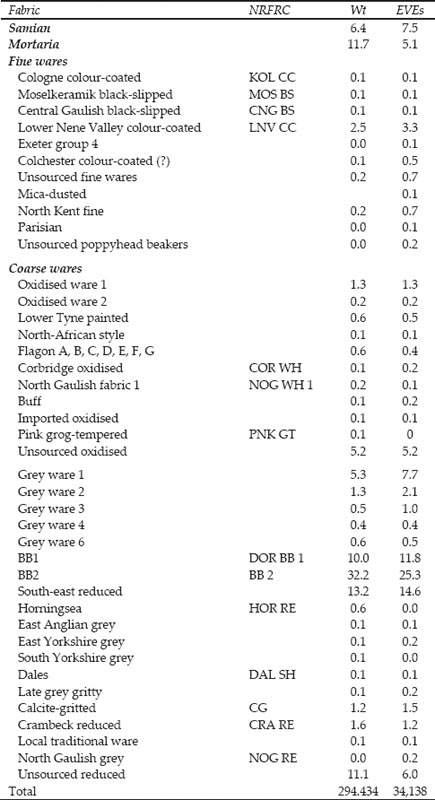

The excavations produced a total of 1099.087kg of pottery, over half of which was unstratified. This very high proportion of unstratified material is partially the result of the destruction of most of the fourth-century levels on the site. The stratified material was fully catalogued and quantified by weight and by measuring rim percentages (EVES), although not by sherd count, with certain assemblages of interest studied in greater detail. The unstratified amphorae, mortaria and fine wares, plus some coarse wares of interest were also fully catalogued.

See Tomber and Dore 1998 for fabrics with NRFRC code in the above table.

Pottery from two other forts in the Lower Tyne Valley have already been studied in some detail, providing the framework for work on the assemblage from Wallsend, since it it clear they all drew on the same sources of supply. The report on the pottery from South Shields included the first quantification of the mortaria and amphorae from the site, and a detailed discussion of its pottery supply, in particular the vessels in BB2 and its allied fabrics that make up a large proportion of the coarse wares during the third century (Bidwell and Speak 1994, 206–42). The report on the pottery from the fort of Newcastle expanded this discussion, with additional detailed study of local traditional wares and the well-preserved late Roman assemblages (Bidwell and Croom 2002, 139–72). The supply of pottery to the region as a whole in the late Roman period has also been investigated (Bidwell and Croom 2010). The study of pottery from the northern frontier region is continuing with the Hadrian’s Wall Ceramic Database project (www.collectionsprojects. org.uk/archaeology/ceramic%20database/introduction.html), which incorporates assemblages from forts, vici and turrets, and hopes to provide a more regional understanding of the material recovered.

LOWER NENE VALLEY COLOUR-COATED (LNV CC)

This is not common before the third century in northern Britain. At Wallsend it was found in the construction levels of the Period 4 barracks and the infill of the hospital latrine drain (Hodgson 2003, 244), and at South Shields it is first found in Severan contexts. It becomes the most common colour-coated ware on the site in the third century, and makes up 70% of the fine wares on the site. The industry supplied primarily beakers, but also flagons and to a lesser extent castor boxes. Many of the vessel forms have a longlife, but a few new types were introduced during the life of the industry. The funnel-necked beaker was first made near the end of the first quarter of the third century, followed in the mid or late third century by beakers based on ‘Rhenish’ forms (such as the funnel-necked beaker with bead rim). Colour-coated bowls in coarse ware forms generally date to c.360 on the northern frontier (Bidwell and Croom 2010, table 4.1).

Beaker, barbotine decoration: 87, 120–2, 268–9, 295

Beaker, funnel necked: 125–7, 129

Beaker, indented: 77–8, 100

Beaker, narrow-mouthed: 294

Beaker, plain-rimmed: 296

Beaker, rouletted decoration: 123, 299

Flagon: 84, 128

Flagon, with moulded mask: 337

LOWER NENE VALLEY PARCHMENT (LNV PA)

Parchment wares, often painted, seem to have been made throughout the lifetime of the industry (Perrin 1999, 108). Although made in a range of forms, flasks are the most common type found in the north. More exotic forms, such as head pots, moulded mask flagons and ring vases also occur, but only in very small numbers.

Bottle: 85, 118

Triple vase: 248

Mortaria made in Nene Valley white ware were also supplied to the fort from the late second or early third century, and the industry became the major supplier of mortaria to the site in the third and fourth centuries. A few grey ware vessels also find their way to the north, but in such low numbers it is probable they are a by-product of the transportation of the mortaria and colour-coated wares.

COLCHESTER?

See Anderson 1980, 33, North Gaulish fabric 2. This ware is used for rough-cast beakers. It is the most common type of second-century fine ware from the site.

Beaker: 2

CENTRAL GAULISH BLACK-SLIPPED (CNG BS)

This was imported from the mid second to the early third century. It is a minor fine ware at Wallsend.

Beaker: 277

MICA-DUSTED

This consists of a number of oxidised fabrics from different sources, with a slip rich in gold-mica. At Wallsend there are indented beakers and plain-rimmed bowls, but it is only a minor fine ware on the site.

Beaker: 76

Bowl: 8 (?), 206, 323

Table 22.10: Stratified ware by fabric type, shown as a percentage

Fabrics represented by less than 0.1% not included in the table: Central Gaulish colour coated 2 (CNG CC 2); North Gaulish colourcoated 1; Ebor red-painted (EBO OX); highly burnished black; Céramique à l’éponge (EPO MA); Verulamium white (VER WH); Lower Nene Valley parchment (LNV PA); Lower Nene Valley grey; Crambeck parchment (CRA PA). Other fabrics found only in the unstratified material: Severn Valley, Crambeck red, southern shell-tempered, Savernake (SAV GT)

Key: NRFRC = National Roman Fabric Reference Collection

CÉRAMIQUE A L’ÉPONGE (EPO MA)

This ware is rare in the region, with only a few vessels known from the northern frontier. The majority of examples in this country come from south-east England, where it is most commonly fourth-century in date (Tyers 1996, 144). Most of the few northern examples have a similar date, although there is a possible sherd from Vindolanda in a late third-century context (Bidwell 1985, 182). Wallsend has produced two vessels, both flanged bowls (Fig. 22.16, no. 112; post-Roman dereliction and ploughsoil). A single flanged bowl is known from South Shields (unpublished, context 3778, fourth-century) and one from Newcastle (Bidwell and Croom 2002, fig. 15.9, no. 99, from an Anglo-Saxon grave).

Flanged bowl: 112

FLAGON FABRIC

Fabric A: Dark grey fabric with orange exterior and a cream wash, found also at South Shields.

Flagon: 117, 292

There are a number of other flagon fabrics (Fabrics B to G), which occurred in small quantities. None illustrated.

BUFF WARE (EXETER FABRIC 440)

Flagons in a buff fabric, probably imported from France. This was produced in the first century and into the early second, and is not a common ware on the site.

Flagon: 266, 287

EBOR WARE (EBO OX)

Made from c.70 to the early third century at York. A small number of vessels are known from the site. The most common type found in the northern frontier zone are the red-painted bowls, but there are also some North African– style vessels.

Dish: 319

Red-painted. See Monaghan 1997, 877–80. Date: Hadrianic-Antonine

Flanged bowl: 93

Late Ebor ware (North African style)

Date: early third century.

Casserole: 275

Head pots: 338–44

Lid: 330 (?)

SEVERN VALLEY WARE (SVW OX)

Small quantities of Severn Valley ware reached the Lower Tyne forts in the second and third centuries. At Newcastle it made up only 0.1% of the pottery assemblage (Bidwell and Croom 2002, table 15.8), and at Wallsend would be even less. Storage jar: 304

LOCALLY PRODUCED GREY AND OXIDISED WARES

A number of fabrics have been identified as those of locally produced wares of the second century. The main products are cooking-pots with groove or lattice decoration (particularly in grey ware), flat-rimmed carinated bowls, and plain-rimmed dishes, but also beakers, storage jars and lids. The finest oxidised fabric was often decorated with white paint (see Lower Tyne painted oxidised ware below). The forms indicate production started in the early second century and continued throughout the Antonine period.

Hard mid to pale grey micaceous fabric. Very fine black and white inclusions, occasionally large. Surfaces are usually darker than the core, particularly noticeable where the surface has been chipped. This is the most common of the fabrics.

South Shields grey ware fabric 1 is the same ware (Bidwell and Speak 1994, 231).

Small jar: 3, 88

Bowl: 262

Bowl, flat-rimmed: 39, 265

Cooking-pot: 9, 10, 18–9, 54, 312

Dish, plain-rimmed: 46

Storage jar: 302

Gritty grey fabric, coarser and softer than grey ware 1. Angular grey and black inclusions, and some linear black inclusions. Occasionally has grey core with paler margins. Rarely burnished, and often with a mottled surface.

Beaker, indented: 298

Bowl, flat-rimmed: 23, 40

Bowl: hemispherical: 29

Flagon, pinch-necked: 293

Cooking-pot: 50–1

Micaceous grey fabric with wide buff core, and scattered, large inclusions, including sandstone. It is not as gritty as grey ware 2, but the individual inclusions can be larger. Cooking-pot, bead-rimmed: 271

Slightly gritty, micaceous orange fabric with medium-sized quartz and plentiful soft red inclusions. There are occasional large or very large inclusions, opaque white or fragments of sandstone. The inclusions are noticeable on the surface of the vessel, although the surfaces are often wiped.

Bowl, flat-rimmed: 22

Bowl, flat-rimmed hemispherical bowl: 47, 94

Dish, flat-rimmed: 95

Dish, flat-rimmed with groove: 111

Probable a variant of the above, but with white inclusions more prominent than the red inclusions, and often more highly fired.

Dish, plain-rimmed: 27

Hard orange fabric often with a grey core or interior and burnished surfaces. Small common inclusions of angular quartz and occasional small soft orange and hard grey inclusions, fragments of sandstone and some mica can be present. The painted decoration is usually cream/white, but at least one vessel also had brown paint. Decoration includes horizontal stripes, zig-zag, diagonal and herringbone lines, open circles and lines of dots. The majority of recognised examples have been found at Wallsend and South Shields, although sherds have been recorded from a number of northern sites, including Carlisle and Cramond.

Beaker: 86

Biconical strainer: 21

Bowl: 48, 259, 320, 326

Cauldron: 20

Closed form: 333

BLACK BURNISHED WARE FABRIC 1 (DOR BB1)

The two main suppliers of coarse ware to the site during the second century were the BB1 industries and the local production sites set up by the military. In the early part of the third century, little BB1 reached the site, but from the late third century, when the supply of BB2 was in decline, BB1 again began a source of supply. Most of the BB1 from the site comes from Dorset, but there are small quantities of BB1 from other sources, such as Rossington Bridge.

Bead-rimed jar: 11, 72, 132

Bowl and dish, flat-rimmed: 24–5, 57–8, 62, 273

Bowl and dish, plain-rimmed: 191–9

Bowl, plain rimmed with groove: 41, 56

Bowl, flanged: 230–44

Cooking-pot: 12–3, 55, 66, 141–3

BLACK BURNISHED WARE FABRIC 2 (BB2)

This ware is present in small quantities from the late second century, but becomes, with its allied industries, the major coarse ware supplier in the third century. For discussions of the dating, see Bidell and Speak 1994, Bidwell and Croom 2002, 153, 169, and Hodgson 2003, 244. By the 270s at the latest, BB1 had begun to supply pottery in some quantity again, but it appears that some BB2 continued to reach Wallsend until the final quarter of the century. The site has produced 13 examples of flanged bowls in BB2, dating to after c.270. The fort at Newcastle, further upriver, has also produced a number of these bowls, but surprisingly few have been found at South Shields, even though the pottery supplies for Wallsend and Newcastle must have come through its port.

Beaker: 63, 131

Bowl and dish, bead-rimmed: 207, 274

Bowl and dish, plain-rimmed: 200–2, 284

Bowl and dish, plain-rimmed with groove: 110, 203–4

Bowl and dish, rounded-rimmed: 67, 208–9, 211–29, 256–7

Bowl, flanged: 328

Cooking-pot: 6, 14, 17, 68, 144–52, 254, 313

Cooking-pot, small: 251–3

Miniature dish, plain-rimmed with groove: 98

SOUTH EASTERN REDUCED WARES (SE RW)

Date: mostly third century.

This term is used for a number of different fabrics from several production centres that were in business at the same time as BB2, probably mainly situated in southern Essex (see Monaghan 1987; called ‘fabrics allied to BB2’ in Bidwell and Speak 1994, 228–31). They were imported to the northeast over the same time period as BB2, and at Wallsend are an important source of supply. Cooking-pots were made in a gritty fabric (in particular Gillam 1970 type 151 jars) and in a sandy fabric without any decoration, burnishing or slip. Storage jars were made in a slightly gritty fabric, often with a grey core, and frequently have burnished decoration. Wide-mouthed bowls and flasks could be slipped, burnished or both, the bowls often with a black or dark grey surface and commonly wavy line decoration, and flasks with a speckled light grey surface. The ware appears alongside BB2 from the late second century, but the vessel type Gillam 151 probably only appears in the third century; at South Shields it is first seen in contexts dating after c.220 (Hodgson 2003, 245).

Beaker: 260

Beaker, poppy-head: 101

Bowl, wide-mouthed: 186

Bowl, S-shaped: 82, 109, 187–9

Cooking-pot: 59, 71, 80, 104–5, 153, 155–69, 172–7, 179, 261, 282

Cooking-pot with bead rim: 69, 310

Cooking-pot, Gillam 1970 type 151: 70, 92, 180–1, 314

Flagon: 291

Flask: 119

Storage jar: 15–6, 79, 135–7, 305

HORNINGSEA (HOR RE)

Horningsea ware, always in the form of storage jars, have now been recognised at Wallsend, South Shields (Bidwell and Speak 1994, fig. 8.14, no. 162 and unpublished), Newcastle (Bidwell and Croom 2002, 153), and Benwell (McBride 2010, fig. 3, no. 2). As the jars were probably imported in small numbers at the same time as BB2 and SE RW they are likely to be mainly third-century in date on the site.

Storage jar: 134, 250, 306

EAST ANGLIAN MICA-RICH FABRICS

Grey fabric with abundant, fine muscovite mica on the surfaces.

Platter: 44, 83

LOCAL TRADITIONAL (‘NATIVE’)

This term covers a range of fabrics used for makings vessels that continued the local indigenous Iron Age traditions of pottery making (Bidwell and Croom 2002, 169–70). The fabrics are usually black, sometimes with patchy oxidised surfaces, with a range of large inclusions, and are always hand-made.

Cooking-pot: 185, 311

DALES-TYPE

Vessels without shell-tempering, in the form of Dales ware cooking-pots. True Dales ware vessels were also present. Third-century in date.

Cooking-pot: 182–3

EAST YORKSHIRE GREY

Date: third century

There are examples of pottery from Norton (c.220–80), and from Throlam (mid- or late third century to mid-fourth century) and probably also the other sites of the Holme-on-Spalding-Moor industries.

Beaker, with handle: 133

Bowl, wide-mouthed: 190

Bottle: 301

Countersunk lug-handled jar: 280

Jug: 303

Smith pot: 347

SOUTH YORKSHIRE GREY

A number of vessels are likely to come from the South Yorkshire industries, but this was never a major source of supply. There is also a bowl with internal decoration in a South Yorkshire/Lincolnshire tradition (Fig. 22.22, no. 263). Dish: 263

LATE GRITTY GREY

Date: late third century–fourth century

Hard, mid-grey fabric with common to abundant, large quartz inclusions. Typically found as cooking-pots with everted rims that are flat-topped, cupped or double lidseated. The vessels were both wheel-thrown, and handthrown with the rim finished on a slow wheel. This is one of the most important sources of pottery in the late Roman period in north-east England (for a full discussion of the ware see Croom et al 2008, 229–30).

Cooking-pot: 272

CALCITE-GRITTED (CG)

See Tomber and Dore 1998, 201. The National Fabric Reference Collection abbreviation HUN CG is not used in order to avoid confusion, as the ware includes non-Huntcliff-type vessels. ‘Huntcliff-type’ is used here to refer only to cooking-pots with an internal groove on the rim (Gillam 1970 types 162–3).

Date: small quantities from late third century, mainly fourth century

Calcite-gritted ware was originated in the pre-Roman period and continued to be made throughout the Roman period, but it was only imported to the north-east in any quantity from the late third century. In the north-east the cooking-pot is the most common form found, although some storage jars, wide-mouthed bowls and plain-rimmed bowls are known. The Huntcliff-type rim seems to appear in c.360, before the introduction of Crambeck parchment ware (Bidwell and Croom 2010, 29).

Cooking-pot, with Huntcliff-type rim: 108, 315

Dish, plain-rimmed: 327

Storage jar: 103

CRAMBECK REDUCED WARE (CRA RE)

The reduced ware first reaches the north in the late third century, and continues until at least the late fourth century (Bidwell 1985, 178; Bidwell and Croom 2010). It was supplied in a range of forms, such as bowls, dishes, beakers and water-carrying jars, but not cooking-pots (which seem to have been supplied by the calcite-gritted ware industries which were located in the same part of the country, but not at the same kiln sites). The conical flanged bowl with internal wavy line first appears c.370.

CRAMBECK RED WARE

Red fabric, often decorated with white paint, probably with a similar dating to the painted parchment ware. One example known from the site.

Bowl: 329

NORTH GAULISH GREY WARE (NOG RE).

Date: first to third century.

This ware has been found at South Shields, Wallsend and Newcastle in small quantities. The most common form is the vase triconique.

Vase triconique: 38, 81, 308

GREY WARE 4

A minor grey ware fabric. Hard grey fabric, distinctive due to the plentiful fine white quartz inclusions.

Cooking-pot: 138, 171

Bowl/dish: 205

Lid: 31–2

GREY WARE 6

Grey fabric, distinctive because of the plentiful small and common large black inclusions. A number of related fabrics, with the same common black inclusions, have been found across the eastern section of Hadrian’s Wall. It has been found at a number of turrets along Hadrian’s Wall, mainly between Housesteads and Rudchester, so it is possible that Corbridge could be the source for this ware. It appears to be Hadrianic and Antonine in date.

Cooking-pot: 91, 102

SOUTHERN SHELL-TEMPERED WARE. SEE BIDWELL AND SPEAK 1994, 230.

Jar: 307

SAVERNAKE WARE (SAV GT)

Date: Early first century to early or mid-second century, with Lydiard Tregose kilns possibly continuing into the third or fourth centuries.

This ware usually has a limited distribution in and around Wiltshire and Bath (Tyers 1996, fig. 248), and it has not previously been identified in the north. Two sherds from jars were recovered (F11:07, G11:09, robber trench and unstratified). It is of interest that a sherd of New Forest mortaria, also of very restricted distribution, should also be found at Wallsend.

PINK GROG-TEMPERED WARE (PNK GT)

A sherd of this ware was recovered from the alley deposit (Alley 1; context N05:23). This ware is almost exclusively found in the Northamptonshire and Buckinghamshire region, but two vessels have now been found at Cramond (Ford 1991).

PARISIAN WARE

Date: late first to third century

A small number of sherds in at least three different fabrics, with stamped decoration, including roundels, rosettes and squares.

1. Pale orange fabric, cream to exterior. Fine fabric with very rare larger inclusions, and rare silver mica. Single handle.

2. Colchester?

3. GW1.

4. Hard mid-grey fabric, with slightly paler margins, and occasional black or white inclusions. Burnished on shoulder, with vertical line rouletting on the top part and diagonal line rouletting on the lower part.

5. Dark grey, sandy fabric, slightly micaceous. Burnished under the rim, but otherwise a sandy surface. Linear rustication.

6. BB2.

7. Burnished on shoulder and over rim. Fine micaceous, sandy fabric with buff core and dark grey surfaces.

8. Soft, pale orange fabric with pale brown core. Possibly originally mica-dusted.

See also: Croom 2003, fig. 158, nos 15–9.

LOWER FILL

9. GW1, M05:16.

10. A second, with the rim oval in shape and body slightly flattened before firing. GW1, M05:16, M05:12.

11. BB1, M05:16.

12. BB1, with sooting under rim, M05:16.

13. BB1, M05:16.

14. BB2, M05:16.

DAUB DEPOSIT

15. SE RW. N05:23.

16. SE RW, N05:23.

17. BB2. Four lines incised on top of rim. N05:23. 18. GW1, N05:23.

19. Zone on body left unburnished. Body slightly flattened on one side (cf. no. 10 above). GW1, N05:23, N05:19.

20. Line of white dots, some of which have run. Lower part of body burnished. Most of vessel survives. Gillam 1970 type 174, Cam 302. First half of the second century to late third century or later (Bidwell and Croom 1999, 481). LT OW painted, N05:23.

21. Originally this probably had a spout; Marsh 1978, type 46. Burnished footring. Much of vessel survives. LT OW painted, N05:23.

22. OW1, N05:23.

23. GW2, N05:23.

24. BB1, N05:23.

25. BB1, N05:23.

26. Burnished on rim and exterior. Micaceous grey fabric, slightly sandy, with a dark grey core, white margins and mid-grey surfaces, N05:23.

27. A second, warped in firing so that the rim is out of shape and base is not flat. OW2, N05:23, N05:24.

28. Two surviving repair holes, on non-joining sherds; some sotting on exterior. Sandy dark grey fabric, darker towards the exterior. well-rounded quartz c.1mm across is the most noticeable inclusion, with less common angular grey and plentiful extremely fine micaceous inclusions, N05:23.

29. Poor condition, battered and spalled. GW2, N05:23, N05:17.

30. Soft orange fabric with light grey core. Concentric grooving on interior. Similar to the ‘mortarium-like bowls’ of the north-west, but without the groove on the flange. Cf. Birrens; Robertson 1975, fig. 63, nos 11–2. N05:23, N05:24.

31. Darker surfaces, with uneven colouring. GW4, N05:23.

32. GW4, N05:23.

33. Anaus mortarium, 120–60. See mortarium stamp no. 4. N05:23, N05:19.

34. Anaus mortarium, 120–60. See mortarium stamp no. 10, N05:23, P04:10.

See also amphora Fig. 22.10, no. 5.

UPPER FILL

35. ‘Pink fabric, lighter in fracture; hard, fairly rough with moderate frequency of sub-angular grit inclusions. Traces of white external slipping. Bipartite handle’ (Holbrook 1984, no. 9). Lost. M05:12.

36. Soft orange fabric with scattered red inclusions, some large. Remains of a cream wash, M05:12.

37. Fabric white about rim, rest mid-grey. Burnt, and body spalled. M05:12.

38. NOG RE, M05:12.

39. A second; warped. GW1, M05:12.

40. Approximately one-third of the vessel survives. There is rilling on the interior towards the base, while the base is only 2mm thick in the centre. GW2, M05:12.

41. BB1, P05:16.

42. Anaus mortarium, 120–60. See mortarium stamp no. 9. N05:07.

43. North-eastern, second century. P05:16.

DISTURBED UPPER FILL AND DERELICTION OVER ALLEY

44. Fine grey fabric with darker, highly micaceous surfaces. East Anglian? Burnt white along top of rim. N05:07.

45. White fabric with fine black inclusions and small voids and mid-grey surfaces. Same fabric as no. 90 below. N05:07.

46. GW1, approximately one third of vessel survives, L05:29.

47. OW1, L05:29.

48. Not burnished. LT OW painted, with slight grey core and no evidence of paint. L05:29.

49. Mortarium. North-east: pale orange fabric with wide grey core, with large, soft white inclusions and occasional black linear inclusions. Large red and white trituration grits. Hadrianic/Antonine. N05:07.

CLAY LAYER

50. GW2, F04:12.

51. GW2, F04:12.

DRIP TRENCH

52. Gard orange fabric with dark grey core and a thick cream wash, discoloured in firing to grey on one side, F04:33.

53. Soft, gritty orange fabric, slightly burnt near base, F04:33.

54. GW1, F04:33.

55. BB1, F04:33.

56. BB1, F04:33.

57. Slightly burnt. BB1, F04:33.

58. BB1, F04:33.

RUBBLE OVER ALLEY

59. SE RW, gritty fabric, K05:22.

60. Soft orange fabric with silver mica plates and some brown inclusions. Slightly burnt on the rim, K05:22.

61. Fine, micaceous orange fabric with red inclusions, paler orange margins and finely burnished selfslipped surfaces. The flange has been deliberately removed (50% of vessel survives), G04:15.

62. BB1, G04:15.

PERIOD 1

63. Remains of slip on shoulder and rim. BB2, D10:20.

64. White fabric, with thin brown wash over interior and exterior. E10:43, E10:56, E10:58.

65. Pale orange, slightly sandy fabric with fine red and occasional black inclusions. Darker orange exterior, turning to brown on the exterior. E10:43, E10:58.

66. Burnished decoration on the base. Although there is a complete profile, less than 15% of the vessel survives. BB1, D12:34.

67. Bowl or dish with drooping rim and curved wall. Cf. Monaghan 1987, 5D0.2BB2, E10:76.

PERIOD 3

68. Buried pot, found with stone lid in situ (see stone report, no. 35, and Fig. 25.33). BB2, D11:23.

MID THIRD CENTURY

69. SE RW, E11:14.

70. SE RW, E11:14.

71. SE RW, E11:14.

See also: Croom 2003, fig. 158, nos 11–4.

PERIOD 2

72. BB1, F04:07.

73. Micaceous sandy grey fabric with pale grey core and paler margins and soft black inclusions. Sooting under rim. Cf. no. 106 below. P05:07.

74. White fabric with plentiful fine red and black inclusions. Burnished in bands on exterior, fired to pale orange on the top of the rim, Q05:03, plus Q04:01 (unstratified).

75. Orange fabric with fine red inclusions and paler surfaces, N07:15.

PERIOD 3

76. Hard, micaceous orange fabric, with some sooting on the exterior. Mica-dusted, E13:23.

77. Very dark brown on exterior. LNV CC, E13:13.

78. Very dark brown on exterior, orange round base and on interior. LNV CC, E13:13.

79. Approximately one third of the vessel survives. SE RW, M04:14.

80. SE RW, M04:14.

81. NOG RE, M05:28.

82. Body sherd from an S-shaped bowl, with grooves and burnished tendril decoration. Wavy line is more common. SE RW, P05:04.

83. Highly micaceous grey ware, especially visible on surfaces. East Anglian? Mid-grey core, paler margins and burnished surfaces, M05:28.

PERIOD 4

84. Black colour coat on exterior only, thin and mottled round rim. LNV CC. E13:49,

85. Pale brown/orange stripes. The shape of this vessel is very close to the funnel-necked beakers based on ‘rhenish’ forms (Perrin 1999, fig. 61, no. 173) rather than the narrow-mouthed jars more commonly made in parchment ware (Howe, Perrin and Mackreth 1980, fig. 8, nos 94–5), suggesting a date after the mid or late third century. LNV PA. M14:15, M14:01 (unstratified).

86. Burnished in bands on neck and decorated with thin white paint. LT OW painted. M14:45.

87. Dark brown colour coat. For dolphins on other LNV CC beakers see G. Webster 1989, 6. LNV CC. G11:10.

88. GW1, G04:03.

89. Fine, mid-grey fabric, burnished on exterior. Decorated with grooves and open circle stamps. Globular beakers with a similar profile but different decoration were found at Blaxton kiln site, where it was noted that the form and fabric were related to Parisian ware (Buckland and Dolby 1980, fig. 4, nos 49–50). D13:55.

90. White fabric with fine black inclusions and small voids and mid-grey surfaces. Same fabric as no. 45 above. F12:04.

91. GW6, Q05:28.

92. Buried pot. SE RW, D14:10.

93. Coarse orange fabric with large red and white inclusions. EBO OX red-painted, N15:12.

94. Grey core and pale orange surfaces. Burnished in bands. OW1, G14:20 and G14:01 (unstratified).

95. Roughly burnished. OW1, J15:15.

96. Very fine, micaceous dark grey fabric with pale margins and dark surfaces, with silky finish. Barbotine leafs. Imitation Dr 36s in oxidised or colour-coated wares are much more common than examples in reduced ware. Grey ware examples may have been made in the Doncaster area, where a waster or second was found (Buckland 1986, 21, no. 23), and are also known from the Lower Nene Valley (Perrin 1999, fig. 59, no. 98), Cf. a grey ware imitation Curle 11 from South Shields (Bidwell and Speak 1994, fig. 8.8, no. 16). G11:10. Another sherd of this vessel was found unstratified in the 1997–8 excavations.

97. Hard, mid-grey fabric, slightly sandy. F15:06.

98. Miniature dish, with faint external groove (cf. Monaghan 1987, type 9B5.1). BB2, H05:41.

THIRD CENTURY AND LATER

99. Dark orange fabric with remains of cream wash, E05:04.

100. LNV CC, L05:07 and L05:03 (unstratified).

101. SE RW poppy-headed beaker, F11:18.

102. GW6, F11:17.

103. CG, N05:04.

104. Heavily sooted. SE RW, gritty fabric, overfired, J04:05.

105. SE RW, F11:13.

106. Highly micaceous grey fabric with dark grey core and pale grey margins. Occasional soft black inclusions. Sooting under rim. Cf. no. 73 above, N05:04.

107. Dark grey fabric with fine white quartz and occasional black inclusions. Slightly lighter surfaces, H04:19.

108. CG, N05:04.

109. SE RW, F11:03.

110. BB2, F11:17.

111. OW1, J04:05.

112. EPO MA. A flange fragment, from a second vessel, came from M04:01 (unstratified). P07:08.

113. Dressel 20, E08:29.

114. Gauloise 4, E08:29.

115. Central Campanian, E08:27.

116. Biv, with thick cream wash. E08:29.

117. Almost complete vessel, flagon fabric A, without wash, E08:29.

118. Almost complete jar missing rim, LNV PA, E08:27.

119. SE RW, E08:44.

120. LNV CC, orange fabric, E08:27.

121. Approximately two-thirds of vessel surviving. LNV CC, orange fabric and black colour coat, E08:27.

122. Orange fabric, dark brown colour coat, with barbotine leaves and the tail and hindquarters of a dog. Some sooting on the lower part of the vessel. LNV CC, E08:27.

123. White fabric, tan colour-coat. LNV CC, E08:29.

124. Fine grey fabric with a few dark inclusions. Midgrey colour coat, darker on the exterior. About quarter of the vessel survives. E08:29.

125. Approximately half of vessel surviving. LNV CC, orange fabric and black colour coat, E08:44.

126. Orange fabric, brown colour-coat. LNV CC, E08:27.

127. Black colour-coat. LNV CC, E08:44.

128. Black colour-coat, on exterior only. Probably from a small flagon (cf. Dannell et al 1993, fig. 16, no. 46). LNV CC, E08:27.

129. Buff fabric, black colour-coat, slightly burnt on exterior. Indented beaker with funnel mouth (Cam 403), cf. Colchester: Symonds and Wade 1999, fig. 5.39, no. 61. As this type is usually dated to the fourth century (Bidwell and Croom 1999, 486), this may be part of the later contamination of the cistern fill. LNV CC, E08:27.

130. Fine mid-grey fabric, paler core. Black inclusions create a speckled appearance on the non-burnished exterior. E08:27.

131. BB2, E08:29.

132. BB1, E08:29.

133. One surviving handle. East Yorkshire grey ware, E08:29.

134. HOR RE. E08:29.

135. SE RW, E08:27.

136. SE RW, E08:44.

137. SE RW, E08:27.

138. GW4, E08:29.

139. Slightly sooted under rim. Hard, slightly granular grey fabric with slightly darker surfaces. E08:29.

140. Sooted. Soft micaceous mid-grey fabric, with angular black inclusions, very fine burnishing over rim and shoulder. E08:44.

141. Heavily sooted. BB1, E08:29.

142. Heavily sooted. BB1, E08:27.

143. Sooted. BB1, E08:27.

144. Slight sooting. BB2, with oxidised surface, E08:29.

145. Sooted. BB2, E08:29.

146. BB2, E08:29.

147. Sooted. BB2, E08:29.

148. Slight sooting. BB2, E08:27.

149. Sooting on interior of, and under, rim. BB2, E08:27.

150. Sooted. BB2, E08:29.

151. Heavily sooted under the rim. BB2, E08:44.

152. BB2, E08:44.

153. Sooted. SE RW, E08:27, E08:29.

154. Sooted on exterior of rim. Micaceous grey fabric, with pink core, E08:27.

155. SE RW, E08:29.

156. SE RW, with oxidised surfaces. E08:27.

157. Sooting on body. SE RW, E08:27.

158. Sooted. SE RW, E08:29.

159. Heavy sooting on exterior and over rim. SE RW, E08:44.

160. Sooting on interior of rim and body. SE RW, E08:29.

161. Heavily sooted. SE RW, E08:44.

162. SE RW, E08:27.

163. SE RW, E08:27.

164. Heavily sooted under the rim. SE RW, E08:27.

165. Heavily sooted. SE RW, E08:27.

166. Heavily sooted. SE RW, E08:29.

167. Sooted. SE RW, E08:27.

168. SE RW, E08:27.

169. Heavily sooted. SE RW, E08:27.

170. Hard mid-grey fabric, with fine white inclusions, E08:27.

171. Slight sooting. GW4, E08:29.

172. Heavily sooted. SE RW, gritty fabric with oxidised surfaces. E08:27.

173. Sooted. SE RW, E08:29.

174. Heavy sooting on exterior, and over the rim, including all of the interior. SE RW, E08:44.

175. Sooted. SE RW, E09:44.

176. SE RW, E08:27.

177. Heavy sooting on rim and on body from below the shoulder. SE RW, E08:44.

178. Sooted on exterior of rim. Micaceous grey fabric with pink core. E08:29.

179. Slightly sooted. SE RW, E08:44.

180. SE RW, E08:29.

181. SE RW, E08:29.

182. Dales-type; black fabric with fine mixed inclusions and with pale grey margins, E08:44.

183. Heavy sooting. Dales-type; sandy brown fabric with dark grey surfaces, E08:27.

184. Sooted on interior of rim. Hard, sandy grey fabric with angular black inclusions and pale grey core. E08:29.

185. Hand-made, grey fabric with dark grey exterior and buff interior surface. Highly micaceous gritty fabric, with gold mica plates. Sooting on both surfaces of the rim, and on the body. Local traditional, E08:27.

186. SE RW, E08:29.

187. SE RW, E08:29.

188. SE RW, E08:27.

189. SE RW, E08:44.

190. East Yorkshire grey ware, E08:27.

191. Slightly sooted near base. BB1, E08:29.

192. Heavily sooted on exterior wall and base. BB1, E08:27.

193. BB1, E08:27.

194. Heavily sooted. BB1, E08:44.

195. Slightly sooted. BB1, E08:44.

196. BB1, E08:27.

197. BB1, E08:29.

198. Sooted on top of rim. BB1, E08:27.

199. BB1, E08:29.

200. BB2, E08:27.

201. BB2, E08:29.

202. BB2, E08:27.

203. BB2, E08:29.

204. BB2, E08:44.

205. GW4, E08:29.

206. BB2, E08:27.

207. Mica-dusted. Pink fabric with cream core and orange colour coat. E08:29.

208. BB2, E08:29.

209. BB2, E08:29.

210. Hard, light grey fabric with white inclusions, E08:29.

211. About quarter of vessel surviving, with heavy sooting on base and sides. BB2, E08:27.

212. Slight sooting. BB2, E08:27.

213. Heavily sooted. BB2, E08:44.

214. Sooted. BB2, E08:27.

215. BB2, E08:29.

216. BB2, E08:27.

217. BB2, E08:29.

218. BB2, E08:29.

219. BB2, E08:29.

220. BB2, E08:29.

221. BB2, E08:29.

222. Sooted. BB2, E08:27.

223. About three-quarters of vessel surviving. BB2, E08:27, E08:29.

224. BB2, E08:29.

225. Sooted. BB2, E08:29.

226. BB2, E08:29.

227. BB2, E08:29.

228. Slight sooting under rim. BB2, E08:29.

229. BB2, E08:29.

230. Slightly sooted near base. BB1, E08:29.

231. Sooted. BB1, E08:29.

232. Sooted. BB1, E08:27.

233. BB1, E08:27.

234. Sandy dark grey fabric with brown core. E08:27.

235. BB1, E08:27.

236. BB1, E08:27.

237. BB1, E08:29.

238. Sooted. BB1, E08:27.

239. Sooted. Has traces of decoration, probably intersecting arc. BB1, E08:27.

240. Sooted. BB1, E08:27.

241. BB1, E08:27.

242. Sooted. BB1, E08:27.

243. BB1, E08:27.

244. Sooted. BB1, E08:29.

245. Mancetter-Hartshill, 140–80, E08:29.

246. Lower Nene Valley, 250–300, E08:27.

247. Lower Nene Valley, 230–400. E08:27.

248. Ring-vase with the remains of two holes, with stripes of brown paint. LNV PA, E08:27.

249. Battered rim, and missing (single) handle, but apparently thrown away in one piece. Cream fabric with fine red inclusions, occasionally up to 1mm in size, and less common fine black inclusions, J07:14.

250. HOR RE, H07:03, H07:09.

251. No sooting, but discoloured exterior. Approximately half of vessel survives. BB2, H07:03, H07:09.

252. Heavily sooted over body and rim, with white scale and some burning on interior. Approximately one third of vessel survives. BB2, H07:03, H07:09.

253. Heavily sooted on exterior up to and over the rim, with white scale and a patch of burning on the interior. See graffito no. 45. BB2, H07:09.

254. Sooted on exterior. BB2 with partially oxidised surfaces, H07:03, J07:19.

255. Hard fabric with grey core and thin orange margins and fine black inclusions. Orange interior surface, and grey and white exterior surface. Sooted on body and rim. Import? J07:19.

256. BB2, H07:09.

257. See graffiti no. 61. BB2, H07:09.

See also mortarium Fig. 22.08, no. 4.

PERIOD 1 AND 2

258. Hard, slightly gritty mid-grey fabric, with slightly darker surfaces. K10:28.

259. LT OW painted, thin white paint. D08:12.

PERIOD 2 AND 3

260. Fine soapy fabric with black core, pale grey margins and dark grey interior, as used for poppy-headed beakers. The mid-grey/brown exterior surface has visible soft black inclusions. E08:64.

261. SE RW, E08:56.

262. Rouletted decoration below two grooves. GW1, with mottled exterior. K07:08.

263. Hard grey fabric, with fine black inclusions. Lincolnshire/South Yorkshire. Parallels: Dragonby: Gregory 1996, fig. 20.10, no. 933, fig. 20.25, no. 1322; Newcastle: Bidwell and Croom 2002, fig. 15.6, no. 42. K07:08.

264. Burnished on interior. Dark grey fabric with buff margins and dark grey surfaces; some possible flint inclusions up to 2mm across visible on the surface, some fine quartz and opaque white inclusions visible in the break, K07:08.

265. GW1, N11:23.

THIRD CENTURY AND LATER

266. Buff fabric with traces of slightly paler wash. Holbrook and Bidwell 1992, 66, buff ware, type 2, Neronian to late 70s or early 80s. E08:46.

267. Soft, slightly micaceous orange fabric with worn barbotine decoration. Red exterior and brown interior colour-coat, F04:19.

268. White fabric, light brown colour coat. LNV CC, L08:52.

269. Applied teardrops over rouletting. Slightly metallic brown colour coat. Cf. Castleford: Rush et al 2000, fig. 70, no. 433. LNV CC. H11:33.

270. Hard, micaceous dark grey fabric, burnished on neck. Sooted on lower part of body. J10:25.

271. GW3, H04:24.

272. Slight sooting on the rim. Hard, gritty grey fabric with large rounded white and grey inclusions, H11:39.

273. BB1, E12:30.

274. BB2, with two grooves cut into edge of base. See graffiti no. 53. L12:02.

275. Very hard, gritty orange fabric. The base is burnt brown and both it and the walls are sooted. North African-style casserole. Cf. Swan 1992, fig. 1, no. 24. Late ebor. N11:24, N11:29.

LATE ROMAN AND DERELICTION

276. Hard red fabric with occasional soft black inclusions, and slightly brown surfaces. K10:32.

277. CNG BS. L11:08.

278. Orange fabric, brown exterior and red interior colour coat. Q04:15.

279. Fine sandy grey fabric, burnished in irregular lines on the neck. E11:03.

280. The edge of an indentation on the body indicates this is a counter sunk lug-handled jar. East Yorkshire grey ware. G16:21.

281. Dark grey fabric with occasional large black inclusions, with paler surfaces, not burnished. E11:06.

282. SE RW, F09:07.

283. Hard grey fabric with large quartz inclusions. Mottled black and orange exterior. H10:32.

284. BB2, Q04:12, upper fill.

285. Hard grey fabric with sparse black inclusions, H05:12.

286. Gritty orange fabric, with remains of thin white wash. Scar on underside of rim indicates a single handle, M05:04.

287. Buff ware. Holbrook and Bidwell 1992, 66, type 2. P05:02.

288. Fine orange fabric, slightly micaceous, paler on exterior, E10:01.

289. Soft, fine buff fabric, G14:01.

290. White fabric, slightly cream on exterior round the rim, C11:01.

291. SE RW/poppyhead beaker fabric, G12:01.

292. Flagon fabric A, E07:01.

293. Pinchneck flagon, GW2, D11:05.

294. Brown colour coat, LNV CC, J16:03.

295. Ducks are an unusual form of decoration, although a double row of ducks are known on a beaker from the Pakenham kilns (pers. comm. J. Plouviez). LNV CC, F11:01.

296. LNV CC, G11:01.

297. Hard, slightly gritty micaceous orange fabric, with self-coloured slip. Decorated with thick white paint, noticeably micaceous. M13:01.

298. Indented beaker. GW2, burnt, K03:02.

299. LNV CC, M14:01.

300. Soft pink fabric with wide cream core. Thick tan colour coat, easily worn away, on exterior only. A neck sherd (funnel neck?) in the same fabric but probably from a different vessel, was found in L05:07. G11:01.

301. East Yorkshire grey ware, F11:01.

302. GW1, E12:01.

303. East Yorkshire grey ware, E04:01.

304. Severn Valley, Q05:02.