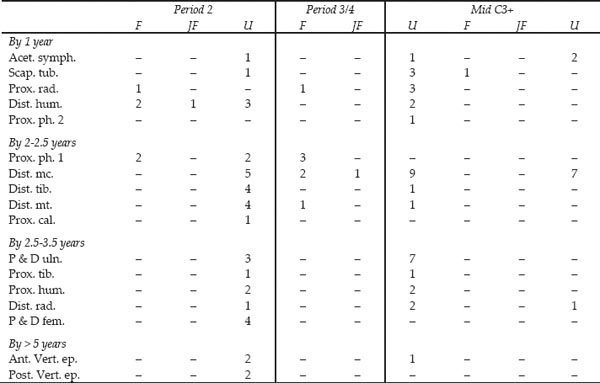

Figure 26.01: Skeletal elements of cattle bones from Cistern 1, context E08:27

It appears from the small quantities recovered that only samples of slag and furnace lining were kept, much of which was unstratified and so cannot certainly be identified as Roman.

1. Area of Building 12, unstratified, L14:44, 1800, WSCA17, 2001.1057

A bead and a fragment of horse harness, broken and partially remelted (see Copper alloy cat. no. 61).

2. Area over Building 8, unstratified, E10:13, 2264, WSCA264

Including fragment of plating.

3. (L:29mm). Building 16, floor, Period 1, M08:26, 2530, WSCA111, 2001.1151

4. Debris over Cistern 1, Roman/post-Roman, E08:13, 2307, WSCA315

5. Unsealed rubble over west praetentura, E05:04, 237, WSCA141

6. Area over Building 14 and Alley 7, unstratified, K11:01, 1709, WSCA318

7. Area of Building 14 and Road 3, no details, K12:03, 1722, WSCA313

8. North intervallum road, phase 3 surface, P04:02, 154, WSCA142

9. Building 2, north wall robber trench, Period 2, N05:17, 364, WSCA918

There were three recessed stones that might have been used as moulds (see stone report nos 50–2), the most interesting of which has possible location pins as if used for a two-piece mould (Fig. 25.32, no. 52).

The evidence for copper alloy working was spread across the site, and showed no concentration in any one area or type of building. There was only one piece (no. 3) from Building 16, identified as a workshop.

The preservation of the bone was generally mediocre, and the assemblage is biased in favour of the larger, more visible and robust bone fragments. An assessment of the complete surviving assemblage provided a quite restricted species list, with the majority of bones coming from the domestic animals, cattle, sheep/ goat and pig. Cattle bone was present in the greatest number of contexts, while goat was present as well as sheep, which included a polled variant. Horse and red deer were also present, but were not numerous; the red deer elements included meat-bearing bones besides lower limb bones and antler. Roe deer bones were also present, indicating hunted game. The dog bones all appear to be disarticulated fragments with no suggestions of whole bodies. Small mammals were indicated by a single tooth, and shell-fish were sparse.

Detailed study was made of the bones from two deposits of interest, from Cistern 1 and Building 13. The assessment of the assemblage of animal bones identified the late third-century fills of Cistern 1 as being of particular interest. The quantity of bone recovered from this single feature was large in comparison with the majority of features on this site. The assemblage was tightly dated to the late third century and appears to have accumulated over a relatively short time span. The assessment highlighted the fact that there appeared to be an unusual degree of selectivity in the skeletal elements of cattle deposited. The immediate impression gained was that preservation of the bones was marginally better for this feature than the general run of finds.

The majority of the bird bones recovered were associated with the commanding officer’s house (Building 13). The presence of bird bones on this site indicates both a more benign burial environment and refuse originating from a higher status establishment. Work previously done on the animal bone assemblage from the commanding officer’s house at South Shields (Stokes 1992) has already indicated that the provisioning of a commanding officer’s house included items which appear not to have been generally available to the troops. It therefore was deemed appropriate to target this group, both for information on supply of foodstuffs to the residence of the senior officer and for data to compare with an equivalent house at, for example, South Shields.

All fragments of cattle, sheep/goat or pig bone with a ‘zone’, sensu Rackham (1986), or tooth were catalogued, with information on element, epiphysial fusion, tooth-wear and metrical data, where appropriate. All fragments of other species were recorded.

Detailed recording of this group revealed that the standard of preservation was not as good as originally thought; the condition was superficially good but leaching of the mineral content has caused brittleness and surface flaking. The bones are not robust and the extra handling caused by repacking after the assessment and handling for recording has led to a large number of fresh breaks. This disintegration does reinforce the interpretation that the assemblage has not been disturbed between the initial deposition and the excavation.

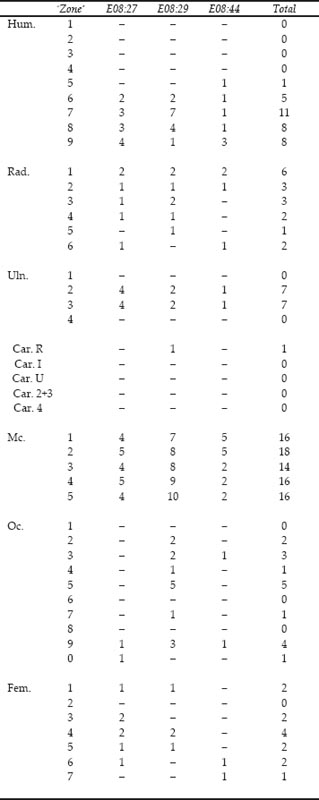

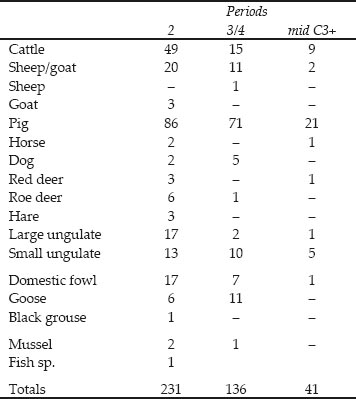

Table 26.01: Fragment counts for the species present in Cistern 1

It can be seen from Table 26.1 that only two contexts within the cistern fills produced abundant finds of animal bones, with a smaller quantity from a third context. Each of the two larger contexts presumably represents a single episode of rubbish dumping from one source. The volume of bone is large but much of the bulk is provided by individual, largely complete, scapulae and lower jaws.

Table 26.01 shows that the overwhelming majority, c.90%, of the identified animal bones deposited in the cistern were cattle or cattle-sized bones. Sheep/goat bones contribute a further 5% of the assemblage. Pig, horse, dog and red deer bones are also present but not in significant numbers.

CATTLE

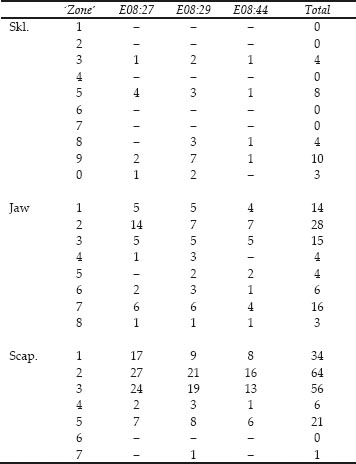

The representation of the skeletal elements of cattle has been previously noted as one of the points of particular interest about this group. Figures 26.01–03 illustrate the frequency of fragments of 20 skeletal elements, chosen as being the most commonly found and representing the whole carcase. To equate with the paired elements, the number of first phalanges has been divided by four while the number of atlas and axis has been doubled.

For context E08:27, Figure 26.01 shows striking peaks of scapula and lower jaw fragments but some surprising absences that cannot be attributed to differential preservation. The calcaneum, astragalus and first phalanx are all extremely dense bones that survive well but are totally absent from the context, together with parts of the pelvis: the acetabulum. The number of maxilla fragments is extremely low compared to the abundance of lower jaw. The other skull and neck bones are also sparse, suggesting processing of the jaw bones separately from the remainder of the head and neck prior to deposition. Context E08:29 in Figure 26.02 has the same abundance of scapula fragments. The lower jaw is still the second most abundant element but the metacarpal is noticeably more abundant than in Figure 26.01. The maxilla and other skull bones are again underrepresented in comparison with the lower jaw. Of the elements not seen in E08:27, none are also absent from E08:29. The information from all three contexts is summed together in Figure 26.03 to show an overall pattern of a superabundance of scapula and lower jaw fragments and a disproportionally high number of metacarpal compared to metatarsal fragments. All remaining elements are represented. Such a pattern is indicative of human selectivity in the disposal of carcase elements in this feature.

What is not immediately apparent from this method of analysis is the paucity of vertebrae and rib fragments. For convenience, these are normally recorded under the “Large Ungulate” category. It can be seen from Table 26.01 how few fragments were designated in this section.

Appendix 1 lists the counts of zones for each cattle element, while Figure 26.04 illustrates the frequencies of the most numerous zone for 14 of the elements considered in Figures 26.01–03. Because there are fewer individual zones than fragments, all the cistern fills are considered together in Figure 26.04. The skull and pelvis are treated as single units for the zone counts. Figure 26.04 should give an indication of the minimum number of individual elements present for cattle and show which elements are over-represented in the fragment counts because of excessive breakage.

The zone frequencies in Figure 26.04 mirror the trends seen from the fragment frequencies in Figure 26.03. The predominance of scapula fragments is still striking. Lower jaw remains the second most common element but the zone frequencies suggest that breakage has enhanced the representation of lower jaw in the fragment counts. The frequency of metacarpal fragments is much reduced for the zone counts, approaching parity with the humerus, but still more abundant than the metatarsus. The remaining elements suggest a similar, low, level of utilisation and discard of undifferentiated parts of the carcase.

Consideration of the zones present for the scapula in Appendix 1, shows that there are surprisingly low numbers of zone 5, the posterior of neck with foramen, compared to zones 1–3 of the glenoid. This is unlikely to be caused by differential preservation as zone 5 is a dense area of bone, unlike zones 4, 6 and 7 which are usually poorly represented. Unfortunately recent cracking and breakage, together with flaking surfaces, has obscured details of the original butchery patterns of this bone. Certainly no evidence was seen for the classic hole in the scapula blade which is normally associated with smoking the shoulder blade meat. Trimming of the glenoid was regularly seen, resulting in lower numbers of zone 1 compared to zones 2 and 3. A proportion of the scapulae appear to have been deposited as more or less complete bones but the impression gained was that many scapulae consisted primarily of the detached glenoid segment with the origin of the spine. The cut marks indicate that the spine was routinely sliced off, hence the low numbers of zone 4.

The lower jaw bones also show evidence for a systematic pattern of dismemberment. The commonly found zones are 1–3 from the front part of the jaw with the incisors and zone 7 at the back of the molar tooth row. Very sparse are zones 4 and 5, the articulation of the jaw with the skull. It seems that the jaw was chopped off leaving the articulation of the jaw embedded in the muscle attached to the skull. These fragments must have been deposited elsewhere on the site, as skull fragments are generally rare in the cistern. Most common is zone 9 on the maxilla, suggesting that some lower jaws may have been dumped with part of the corresponding upper tooth row. It was not possible to match any lower tooth rows with the few upper tooth rows.

Some clear evidence was observed for the longitudinal splitting of long bones through the articular ends for marrow extraction (Stokes 1996, 40). This is reflected in the zone counts by, for example, the higher number of zone 7 on the distal humerus, the medial condyle, compared to the lateral zone 8, and also the proximal radius with zone 1, the medial condyle, compared to the lateral zone 2. Similar butchery was also seen on some metapodials but, particularly for the metacarpal, most of the fragments with corresponding zones appear to have been dumped together.

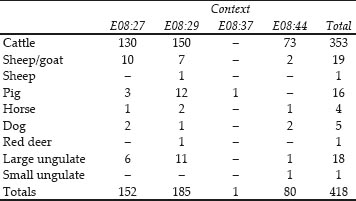

Table 26.02: Tooth wear data for cattle bones in Cistern 1 (teeth in approximate order of eruption)

Key: m = months, U = unerupted/deciduous, S/W = slight wear, H/W = heavy ware Ages after Silver 1969

The bones had been extensively modified, principally by chopping with a heavy cleaver, before disposal. Clear chop marks were observed on 162 identified fragments, 39% of the assemblage. This excludes unidentified fragments and identified fragments where flaking surfaces have obscured such evidence. There is no doubt that these bones had been deliberately selected and dismembered. Two frontal bones demonstrated that considerable effort was expended in removing the horns. One metacarpal and one metatarsal showed signs of burning midshaft. This practice is widespread on Roman sites, particularly in Carlisle (Stallibrass 1991 and 1993). The author believes this process to have served the dual function of liquefying the marrow and making the bone brittle so it could be snapped easily to pour the marrow out, and has carried out experimental work with Mr P. Stokes to demonstrate the hypothesis is plausible.

The cattle supplied to the fort whose bones were finally dumped in the cistern appear to have been mainly mature animals. The tooth wear data in Table 26.02 show a complete absence of young calves with the first molar unerupted and only one first-year beast with molar 1 coming into wear. More numerous are late shedding deciduous teeth and permanent teeth coming into wear, probably from second- to thirdyear animals, but most common are permanent teeth in full wear from third-year and older animals. This is further illustrated by the Mandible Wear Scores in Figure 26.05 from the jaws with complete tooth rows surviving. Only one younger, second year, animal with molar 2 coming into wear is present at MWS 15. The remaining ten jaws span MWS 37–45. These have all molars present and in wear. By analogy with my own reference collection of Dexter cattle mandibles, those jaws at MWS 44–45 represent animals at least 10 years old and probably several years older. Breakage of the jaws has obscured the incidence of congenital absence of premolar 2 but one example was noted, as well as an example of malocclusion on molar 3.

Tooth wear data is spares for the pigs but Table 26.02 suggests the presence of mainly second-year animals with permanent teeth coming into wear. There appear to be no very young or aged pigs represented by teeth.

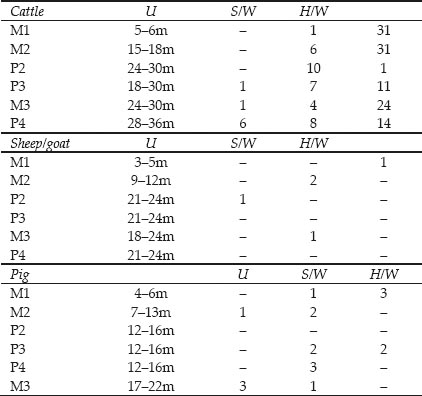

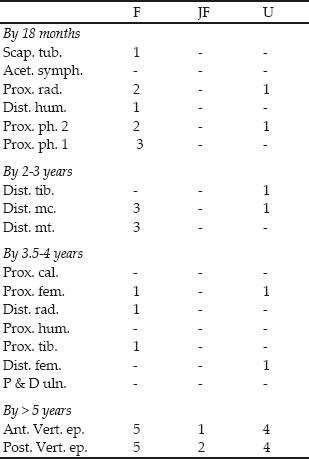

The epiphysial data in Table 26.03 complement the tooth wear data in showing that the majority of the bones are from adult animals with fused epiphysial ends. Only one unfused scapula is present and was noted as deriving from a calf. The few remaining unfused epiphyses are from the later fusing elements and probably correspond with the limited cull of second- to third-year animals postulated from the teeth.

Only four bones were sufficiently complete to be used for estimates of withers height, using the factors of Zalkin (1960) where the sex of the animal is not known. Three metacarpals indicate withers heights of 1.02m, 1.11m and 1.14m, while two metatarsals indicate heights of 1.08m and 1.14m. The distal metacarpal was the only element to provide a reasonable sample of metrical data. The nine bones in Figure 26.06 appear to fall into two groups. The smaller range from 50 to 53mm and may be female while the larger range from 56 to 59 mm and may be male. The single cattle skull with horn cores attached appeared feminine.

Table 26.03: Cattle epiphyses in approximate order of fusion, from Cistern 1

Key: F = fused, JF = just fused, U = unfused Ages of fusion after Silver 1969

OTHER SPECIES

Bones from animals other than cattle appear to be incidental refuse included in the cistern fill. Of these, sheep bones are the most common. One skull with feminine horn cores had been split sagitally and a further two bones had been chopped. Two fused and two unfused bones were seen and one lower jaw with all permanent molars present but little wear on molar 3, so probably aged about two years at death. Further evidence for the culinary source of this deposit lies in the chop marks seen one pig bone, one horse bone and the red deer bone.

Two of the dog bones were sufficiently complete for withers height to be estimated using the factors given by Harcourt (1974, 154). Both bones are probably from one animal with a height of about 28 to 30cm. Dogs obtained access to some of the bones before they were tipped into the cistern as canid gnaw marks were observed on six cattle bones and four sheep bones.

The late third-century fills of the cistern have produced a most unusual, specialised deposit of cattle bone. There is evidence for considerable human selectivity, suggesting that much of this refuse derives from specialised processing involving principally the scapula and lower jaw of cattle, with some marrow extraction from other major limb bones, particularly the metacarpal. The low numbers of skull fragments suggest that primary slaughter waste was not included in this deposit, likewise the low numbers of ribs and vertebrae suggest that general food preparation and consumption waste has not been dumped here. A small proportion of general culinary waste may be indicated by the inclusion of bones from species other than cattle.

Some possible reasons for the utilisation of bone marrow have been discussed by Stokes (1996). For large deposits of highly fragmented limb bones, the “soup kitchen” hypothesis postulated for Zwammerdam (van Mensch 1979) has been discredited and, in any case, this assemblage is not of a comparable scale. The soup suggestion may, however, be relevant to the lower jaws from the cistern. These have been broken in such a way as to open the marrow cavity. Sadly, there are no surviving recipe collections from Roman Britain. However, in more recent historical periods ox cheek soup frequently figures in recipe collections, often with the admonition to first break the bones (Raffald 1970, 5). Finds of cattle scapulae with the glenoid trimmed and a hole in the blade are frequently encountered on Roman sites and are generally interpreted as evidence for brined and smoked shoulder beef. Clear evidence for the meat hook holes in the blade was missing for the scapulae from the cistern but a similar product may be envisaged, perhaps boiled salt shoulder beef rather like a modern ham with the glenoid used to hold the joint for carving. A minimum of 49 scapulae and 23 lower jaws would have provided a substantial amount of food, without taking into account the meat and marrow attached to the remaining bones and any vegetative waste for which the evidence has not survived. This is not catering by barrack block but rather by garrison, suggesting a special meal for a special event. Saturnalia or some other comparable religious or military festival may have coincided with the decommissioning of the cistern which became the fortuitous repository of this unusual assemblage.

Detailed recording of this group revealed that the standard of preservation was generally better than the average of the assessed contexts. This is reflected in the presence of bones from small and juvenile animals. It can be seen from Table 26.04 that Period 2 produced the richest group both in terms of numbers of identifiable bones and species diversity. The Period 3/4 group has fewer identified bones and a noticeable absence of some species present in Period 2, in particular goat, horse, red deer and hare. While the numbers of fragments are small, Table 26.05 indicates some further, interesting differences between the phases. Cattle bones are most abundant in Period 2, decline in proportion in Period 3/4 but increase again from the mid-third century, though not to the level of frequency seen for Period 2. The sheep/goat bones remain proportionally constant in all three phases, but from the mid-third century+ the sheep/goat bones are more numerous than those of cattle. Pig bones are the most abundant finds in all three phases but the proportion fluctuates in relation to the cattle bones, with pig bones peaking in the mid-third century+ which has the lowest proportion of cattle bones.

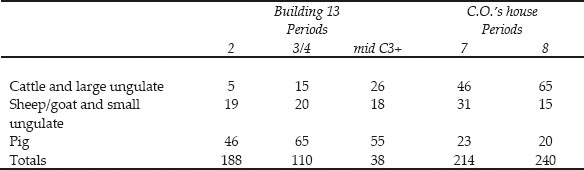

Table 26.04: Fragment count for the species present in Building 13

This contrasts strongly with the findings of Stokes (1992) for the commanding officer’s house at South Shields. The methodology used is not totally compatible with the present system but data thought to be equivalent are presented in Table 26.05. The chronological decline of cattle bones at Wallsend contrasts with a substantial increase in the proportion of cattle bones between Periods 7 and 8 (late third and fourth centuries) at South Shields. Sheep bones are considerably more abundant in Period 7 at South Shields than any of the Wallsend phases, but decline in Period 8 to a similar proportion to that encountered at Wallsend. Pig bones at South Shields do not approach the abundance found at Wallsend but do not vary so dramatically between the two phases as the cattle and sheep. These data suggest that the choice of the Wallsend household lay between cattle and pig meats, with a standard supply of sheep meat. Conversely the South Shields household appears to have chosen between cattle and sheep meats, with pig meat as a standard supply.

The changes between Periods 2 and 3/4 at Wallsend may suggest a change in the tastes of the people occupying the house or a change in housecleaning routines, removing more of the larger cattle and deer bones but not the smaller pig bones.

CATTLE

Only Period 3 produced sufficient cattle bones for any analyses. All parts of the body are represented with similar numbers of bones from the feet, fore and hindquarters but far fewer from the head, including loose teeth. As can be seen from Table 26.06, the surviving bones are predominantly from adult animals, only a quarter of the epiphysial ends found were unfused. There were noted three bones from infant, bobby, calves and one bone from an older, veal, calf. No calf bones were seen in Period 3/4 but the equally small group from the mid-third century+ produced three bones, all from the forequarter of a veal calf.

SHEEP/GOAT

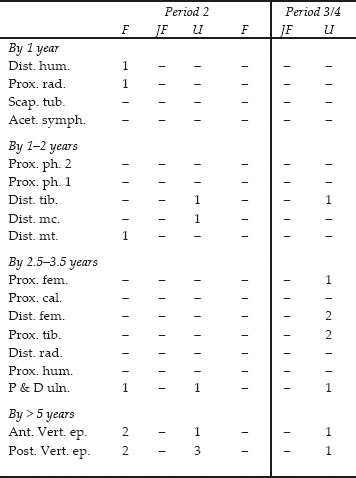

Both sheep and goat are present. Goat is represented by two joining halves of one horned female skull found in N11:29 and N11:31. Sheep is indicated by a polled female skull from M12:44. A further metatarsal from M12:37 falls within the goat side of the range established by Rowley-Conwy (1998, 252) for the plot of Greatest Length against Distal Breadth. The remaining bones in the sheep/goat category appeared to be sheep rather than goat. In general all parts of the body are represented in Period 2, with the exception of the small toe bones that are easily missed during excavation. Period 2 also has roughly equal numbers of fused and unfused epiphyses in Table 26.07, while the mid-third century+ has only unfused ends. This apparent difference may simply be a product of small sample size. Three bones from young lambs and one further bone from an infant lamb were seen in Period 2. These tiny bones give an indication of the season of these deposits. Even unimproved cattle can calve all year round, pigs can farrow twice a year but sheep lamb once in the spring.

Table 26.05: Relative proportions of domestic species present in Building 13, Wallsend and the Commanding officer’s house, South Shields, shown as percentages

Table 26.06: Cattle epiphyses in approximate order of fusion, from Building 13

Key

F = fused, JF = just fused, U = unfused

Ages of fusion after Silver 1969

PIG

It is appreciated that the sample size is very small. Nonetheless Figures 26.07 and 26.08 suggest a meaningful change in body part representation between Periods 2 and 3/4. In Period 2, Figure 26.07 shows that bones of the head, forequarter and hindquarter occur in similar proportions. In Period 3, Figure 26.08 shows that bones of the forequarter are most common. The elements of the head and hindquarter occur in similar proportions but at roughly half the abundance of the forequarter.

Table 26.07: Sheep/goat epiphyses in approximate order of fusion, from Building 13

Key: F = fused, JF = just fused, U = unfused

Ages of fusion after Silver 1969

As can be seen from Table 26.08, the majority of the pig bones were from immature animals with unfused epiphysial ends. Period 3/4 appears to have more slightly older animals, with fused bones, from the trotters. This is deceptive as a large proportion of the unfused bones in Period 3/4 are from piglets. Period 3/4 produced 26 piglet bones compared to 9 from Period 2. Many of these were probably deposited in articulation but it is not now possible to reconstruct how much of a body was deposited where. These tiny bones are not easy to recover by hand and these deposits would have benefited from whole earth samples to recover the full assemblage. Assuming these bones all derive from culinary waste from the consumption of sucking pig, the piglets appear to have ranged in size from perinatal to several weeks old, in comparison with the wild boar piglets in the reference collection of the Biological Laboratory. One piglet bone from Period 3/4 had been nibbled by a rodent, the only evidence from this assemblage for the presence of commensal species.

Table 26.08: Pig epiphyses in approximate order of fusion, from Building 13

Key: F = fused, JF = just fused, U = unfused

Ages of fusion after Silver 1969

HORSE

Remains of horse were sparse with two elements from Period 2 and one from the mid-third century+. Those from Period 2 are a tooth and a metapodial. That from the mid-third century+ is also a metapodial but appears to be an offcut from the manufacture of an artefact. The shaft has been neatly chopped all round to detach the distal, fused, articulation from the shaft. The blows were carefully angled from the distal end and are dissimilar to the butchery marks generally encountered.

DOG

Dog bones were encountered in Periods 2 and 3/4. Period 3/4 produced one intact, fused, tibia from which an estimated height of 25cm was calculated using the factor of Harcourt (1974, 154). The midthird century+ produced three bones, with unfused epiphyses, from one immature animal from contexts M12:17 and M12:42 (backfill of the eastern hypocaust). These would appear to indicate a disturbed burial. Stokes (1992) identified only two dog bones, one from each phase, from the commanding officer’s house at South Shields. These were also from fairly small, lap-sized, animals.

RED AND ROE DEER

Red deer bones were not numerous but the presence of two lower limb bones and a jaw in Period 2 does imply the supply of a carcase to the residence. A further lower limb bone was recovered from the midthird century+ and an antler fragment from a post-Roman context. Roe deer bones were most numerous in Period 2 and comprise five lower limb bones and a jaw, with a further lower limb bone from Period 3/4. For the small size of the assemblage, deer bones are more common at Wallsend than at South Shields, though the latter site produced more antler.

HARE

Three hare bones were found in Period 2. Hare was present only in period 7 (late third or early fourth century) of the commanding officer’s house at South Shields and the remains were not numerous.

BIRDS

Domestic fowl and goose bones were found, overall, in similar numbers. Period 2 produced more fowl than goose bones with the reverse in Period 3/4. Black grouse, represented by one bone in Period 2, is the only wild species present. This is a game bird highly esteemed for the table and consonant with the status of the commanding officer.

MOLLUSCA AND FISH

Shellfish were remarkably sparse with only mussel shells recovered from Periods 3/4 and the mid-third century+. This contrasts with South Shields where six types of marine mollusc shell were identified from the commanding officer’s house. The generally inhospitable soils at Wallsend have militated against the general survival of fish bone. However the exceptional preservational conditions associated with the commanding officer’s house have led to the recovery of tiny fragments of fish bone from Periods 2 and 3/4. While these cannot be identified, their presence does indicate that fish was procured for consumption.

It is appreciated that the assemblage under discussion is extremely small and subject to inherent bias. Nonetheless, the deposits associated with the commanding officer’s house are notable for the better condition of the bones which has led to the survival of bones from small and juvenile animals. This in turn has led to an enhanced species list which is dominated by pig rather than cattle, with goat attested as well as sheep. Hunting, particularly in Period 2, is indicated by bones of both red and roe deer, hare and black grouse.