His Blind Power, 1913. A Lubin production with Romaine Fielding (right) as writer, director, and lead. (Robert S. Birchard Collection)

THE FOREWORD to the script for Human Wreckage, written in 1923, declared that habit-forming drugs were the gravest menace confronting America:

“Its victims, numbering hundreds of thousands, are scattered throughout the length and breadth of the land. They range from children to old men and women and embrace the entire social scale from the dock laborer to the bank president. Every profession, every walk of life, has contributed its quota to Dope and the sacrifice continues daily.

“Immense quantities of morphine, heroin and cocaine are yearly smuggled into America across the Canadian and Mexican borders. The dope traffic has grown alarmingly within the past ten years and is now of gigantic proportions.”1

In 1900, if you wanted a stimulant or a painkiller, you simply went to your corner druggist and bought opium or its derivative, morphine; the cost was a few pennies.2 During the Civil War, injured soldiers had been given morphine and found it so effective they continued using it after the war, recommending it to friends and relatives.3 Addiction spread so rapidly it became known as “the American problem.” Yet if you, like one out of every 400 Americans,4 became an addict, few people noticed because your supply route was assured. You were no more of a social outcast than is a diabetic today.

No laws banned the sale of narcotics, and few people objected to their use on moral grounds. Opium joints were the object of curiosity and opprobrium because the dens were operated by the Chinese and the whole thing was so thoroughly un-American; nevertheless, tour guides included them in their itineraries, and several films were made about them, including Chinese Opium Den (1894), a Kinetoscope loop, and Rube in an Opium Joint, made for the Mutoscope in 1905, which showed a slumming tour visiting a Chinatown den. (Indeed, many were operated purely for tourists.) For patent medicine manufacturers (the largest single user of newspaper advertising space), addictive drugs were ideal ingredients, as they ensured that customers returned for more. It was only when muckraking journalists began to reveal, in 1904, that infants were being stunted or killed by the opium in patent medicines that some states passed laws to curb its distribution.

In 1898, a German researcher had produced a wonderful new substance called heroin from a morphine base. It was introduced under that name as a cough suppressant by Bayer & Company. Everyone believed it was nonaddictive, and it was even used to cure morphine addiction.5 Doctors prescribed it for birth pains (the mother in Eugene O’Neill’s Long Day’s Journey into Night becomes addicted in this way). Not for years were its addictive properties suspected.

Coca-Cola, whose formula involved the use of both the coca leaf (source of cocaine) and the cola nut (which contains caffeine), was introduced in Georgia in 1886 as a headache remedy. In 1906, after the passage of the first Pure Food and Drug Act, the federal government investigated Coca-Cola; the manufacturers faced criminal charges for adulteration and misbranding.6 The company eventually managed to outmaneuver the Supreme Court, and it was never proven that Coca-Cola contained cocaine. But if it had, it would not have stood alone. In 1909, thirty-nine soft drinks, available to children, were laced with the drug.7

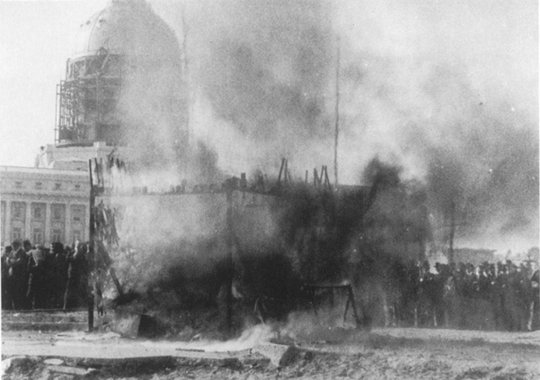

Agents burning opium in front of the San Francisco City Hall (under construction) in 1914. Frame enlargement from a newsreel in the Bay Area Archive. (Bert Gould)

And the case gave rise to one of the first films to show the danger of the drugs, D. W. Griffith’s For His Son (Biograph, 1912): “A physician, through his love for his only son, whom he desires to see wealthy, is tempted to sacrifice his honor by concocting a soft drink containing cocaine, knowing how rapid and powerful is the hold obtained by cocaine.… The drink meets with tremendous success … but his son cultivates a liking for it. The father discovers his son’s weakness too late, for he soon becomes a hopeless victim of the drug.”8

Griffith and author Emmett Campbell Hall called the drink Dopokoke and gave it the slogan “For That Tired Feeling.” The son (Charles West) eventually dies and the plight of the father (Charles Hill Mailes) is summed up in the closing title: “He did not care whom he victimized until he found the result of dishonor at his own door.”

With the passage of the Opium Exclusion Act in 1909, opium smuggling became big business in the United States. In 1912, Selig made a film about it called The Opium Smugglers, describing the operations on the border between Montana and Canada. The Harrison Narcotics Act was passed in 1914. But it was 1913, the year of the white slave hysteria, which marked the beginning of the flood of drug pictures. A three-reeler called Slaves of Morphine was released that year by Leibow’s Features (probably the Danish Morfinisten [1911]). And in San Francisco, the chief inspector for the State Board of Pharmacy broke up a morbid tableau. A Chinatown guide had rounded up a group of “derelict dope fiends” for a film to be made by a local picture concern. The addicts were each paid a dollar, supplied with “hop,” and filmed injecting it into their arms. The scene was described as “very realistic—particularly so after the pharmacy official arrived.”9

Ordinary moviegoers, few of whom were aware of the drug problem, were astonished by these pictures. But the trade press took exception to them. “While the police are lenient,” said Variety, “and well known but weak-minded people will endorse ‘vice pictures,’ feature films like The Cocaine Traffic will be publicly exhibited for the prime purpose of making money for the promoters, while at the same time spreading an unhealthy education amongst the young.”10 A film like that, in a small town, would corrupt the morals of the entire place, Variety added.

The Cocaine Traffic (1914), better known as The Drug Terror, was directed for the Lubin Film Company by Harry Myers, who played the drunken millionaire in Chaplin’s City Lights. It was written by Lawrence McCloskey “with the assistance and approval of the Director of Public Safety and the Police Department of the City of Philadelphia.” The story was strong stuff: Spike Smith, a cocaine sniffer, induces his former boss, Andrews, to become a dealer on the side. Dealers were now regarded as worse than addicts: “Low as Spike Smith had sunk, Andrews had now fallen to a greater depth.”11 Spike’s wife leaves him, and he becomes a drifter in the Tenderloin, where coke sellers are plentiful. When a police raid cuts off his source of supply, he returns to Andrews, now a wealthy cocaine king, whose daughter is about to marry Hastings, a society man. Spike acquires cocaine and for good measure hooks Hastings—who passes on the habit to his new wife. Andrews has to take his daughter into a sanitarium and watch her suffering. Hastings sinks to the level of derelict and visits Andrews one night in search of the drug. After a fight, he kills the cocaine king. The house burns down with both men in it.12

Variety called it six reels of misery: “When one sees the endorsements and reads the press stuff on these ‘vice films’ to ‘save souls’ it is almost laughable, when the self-same pictures are sending more souls to hell at 25 cents each at the box office than were ever captured by all cadets.”13

These drug films needed an aura of respectability to get them past the censor boards. Medical people provided endorsements because they felt that any propaganda against drugs was worthwhile, but they did not always come cheap. For the use of his name in connection with The Cocaine Traffic, Dr. Frederick H. Robinson, president of the Medical Review of Reviews, was said to have been promised 5 percent of the gross.14 When the picture opened in Detroit, its press agent announced that Dr. Robinson would make a personal appearance, but there was some dispute about his commission and he refused to come. A Detroit paper got wind of this and sent him a wire. Dr. Robinson wired back to stop the use of his name. The newspaper attacked the film, the police condemned it, and the effect of the row on the box office was a loss for the film of $2,175.15

The Drug Traffic, made by Eclair, was a 1914 two-reeler which reflected the change in the law regarding the sale of narcotics. The synopsis is an eye-opener: “Johnson, a druggist, plies an illicit trade in cocaine and morphine, which he sells slyly over his drug counter to selected clientele. In his richly furnished office, the head of the Kurson Chemical Company (Alec B. Francis) counts the receipts from the Kurson Consumption Cure, a patent medicine which contains a large amount of morphine. He also sells morphine to Johnson.”

Johnson’s daughter, Lucille (Belle Adair), suffers severe headaches, and she and her fiancé, James Young (Stanley Walpole?), drop into the drugstore for a remedy. There they see morphine being sold to a young boy. They follow him to a hovel, where they find his mother struggling in agony on the floor. Beside her, Lucille sees a bottle of the Kurson Consumption Cure. When she sniffs the bottle she gets her first smell of the intoxicating drug. The police are called. The old woman, deprived of her source, dies, and Lucille and James take charge of the boy.

Lucille becomes an addict herself and sneaks out one night to her father’s home to obtain morphine. The boy follows her and reports to James. Johnson is arrested, but nothing can be done for Lucille, who collapses in the street and dies at the police station. Distraught with grief, her fiancé swears to kill the man at whose door he can lay the crime.

At the prison, Johnson points to Kurson, who has been summoned by James, and says, “There is your man.” The revolver falls from James’s nervous hand, and he falls across the body of Lucille as they lead Kurson to a cell.16

The United States discovered that it had become the most drug-afflicted of all nations, and sweeping legislation was planned to stamp out cocaine once and for all. But while newspapers gave more space to drugs than virtually anything else, picture people were even more likely to exploit the situation. Herman Lieb, who had written and acted in a vaudeville sketch about drug addiction, adapted it as a six-reeler called Dope. It was criticized for its sensationalism and for its vice scenes—a middle-class mother forced by her cocaine habit to become a streetwalker.

A husband becomes an addict by taking headache powders in The Derelict (1914), a Kalem two-reeler written by James Horne and directed by George Melford. The powders are administered by a false friend (Douglas Gerrard), who has his eye on the man’s wife. The picture was unusual in that for once there was a happy ending—the false friend has a change of heart, the husband fights off the drug habit with the help of a sympathetic doctor, and his married life picks up where it broke off.

The Secret Sin (1915), written by Margaret Turnbull and directed by Frank Reicher for Famous Players, featured Blanche Sweet in a double role as twin sisters. Grace experiments in a Chinatown opium den and falls ill; when a doctor prescribes morphine she becomes addicted. Her sister tries to rehabilitate her, but Grace conceals her supply and even makes out Edith is the addict. Technically, the film shows no advance on the old Biographs, but it is full of startling facts. Fake prescriptions are provided by an uptown “resort.” When it is raided, the prosperous clients are driven to slumming in Chinatown, where they must distinguish between the fake dens, set up for tourists, and the real thing.

The New York Dramatic Mirror thought The Secret Sin a good picture, even though it lacked suspense and the action was slow. The reviewer criticized one scene in particular: “It is doubtful whether the fake doctor’s prescription calling for morphine would ever have passed the scrutiny of a reputable druggist.”17 Alas, the film did not have to resort to fiction; this kind of thing happened every day.

Once it became clear that drugs were a box-office draw, pictures which had nothing to do with the subject dropped dope into the plot in the hope of higher grosses. Bondwomen (1915), directed for George Kleine by Edwin August, was a study of the average American wife, showing the humiliation that may be caused by the lack of an independent bank account. “A secondary theme has been introduced showing the effects of cocaine, and much footage is used up in the exposition of a new cure for this soul-destroying habit—which is very fine, except that it has no basis of medical fact.”18

These were the days when a director would see an article in the newspaper and sit down and write a script about it, as John Noble did when he read about the addiction of messenger boys to cocaine. The result was Black Fear (1916). Although he praised it as “a mighty good picture,” the reviewer for the New York Dramatic Mirror called the story “exceedingly complicated.” It opened with the statutory allegorical scene in Hell, then showed in detail how messenger boys doing night work are kept awake with small doses of cocaine; soon they are confirmed addicts and cannot live without the drug. The film also showed how boys were used to obtain the drugs and portrayed the manner in which they were forced to become “intimately acquainted with all forms of vice.”19

The impact of these crusading pictures was diminished by luridly melodramatic drug films such as The Devil’s Profession (1915), an English production in which a doctor runs a sanitarium whose patients are kept under the influence of drugs. One of his patients eventually turns on him and blinds him with vitriol.20

Originally called Cosette, The Rise of Susan (1916) was a World Film Production starring Clara Kimball Young. It was written by Frances Marion, impressively photographed by Hal Young, and adequately directed by S. E. V. Taylor. The surviving print has surprisingly little punch, despite its theme—perhaps because three reels are missing, but more probably because the acting by Young as Susan is uninspired. It is a story of a girl who poses as a countess, falls for a wealthy young man, and loses him to another girl, Ninon (Marguerite Skirwin), a drug addict. Nevertheless, it contains fascinating glimpses into this taboo subject: Ninon possesses a beautifully bound book which, when opened, proves to contain her hypodermic needles. When her mother is confronted with it, she insists it belongs to her physician and is deeply insulted by the suggestion that her daughter might be an addict. The film demonstrates that drugs lead to insanity. Susan becomes a nurse and looks after Ninon, who attacks her with a pair of scissors and flings herself out of the window. Susan is blinded, yet still wins the wealthy young man.21

The trade press detested it. Wid’s described it as a hackneyed melodrama, the story “painfully ancient,” with far too many titles, “the effect being at times of reading the plot rather than seeing someone trying to act it.”22

Drug films became a glut on the market, and when The Devil’s Needle came out in 1916, Variety greeted it glumly: “The drug story has been so often sheeted there is nothing left for it.”23 Yet this was a relatively sober and compelling story, showing how easy it was to become dependent on narcotics. Produced at Fine Arts, written by Chester Withey and Roy Somerville and directed by Withey (his first film), it starred Norma Talmadge and Tully Marshall, who was picked for this role because of his highly acclaimed portrayal of the dope fiend in Clyde Fitch’s play The City. In The Devil’s Needle, he plays John Minton, “an artist of the modern school”—neurotic, chain-smoking, constantly dissatisfied. His model, Renée (Norma Talmadge), relieves the tedium of posing with an occasional injection. (When the film was reissued in 1923, a title explained her addiction as a habit contracted during wartime service as a nurse!)

Howard Gaye, Tully Marshall. Marguerite Marsh, and Norma Talmadge in The Devil’s Needle, 1916.

When the artist sees what she is doing, he is fascinated and appalled. “You don’t know its advantages,” she says. “It kindles the fires of genius—it is inspiration ready-made.” Against his better judgment, he tries it and finds he works with greater intensity. He falls for, and marries, another model, to Renée’s dismay, but soon becomes an almost hopeless addict. Worse, he tries to addict his wife, and eventually attempts to kill her. He is taken for a cure in the country, where hard work and fresh air restore his health. His wife is captured by gangsters and Renée sacrifices herself that the couple may be reunited. Wid’s thought this appropriate, since she hooked Minton in the first place.24

The underworld scenes, shot in the Plaza district, contain the most graphic coverage of the slums of Los Angeles of any surviving picture. But Variety had nothing but scorn for the idea that the artist could kick the habit with a trip to the country. “If it’s true that hard manual labor will kill the taste for drugs, Chester Withey … deserves to have a niche in the film discovery hall.”25

The Ohio board of censors rejected The Devil’s Needle in its entirety on the grounds of its subject. Informed of its value as an agent of reform, the board confessed it had made a mistake. The picture was passed—in its entirety—and opened in Cleveland.26 (Such occasions were extremely rare in the history of censorship!)

Fine Arts contributed another story to the drug saga, although they disowned it. The Mystery of the Leaping Fish (1916) has become a cult film because of the way it deals with cocaine. D. W. Griffith is supposed to have written the story, although the film credits it to Tod Browning.

Tod Browning sounds more likely; this is one of the most bizarre films ever produced. Perhaps if he had directed it, the result might have made more sense. What is surprising is to find Douglas Fairbanks in the lead. His costar was Bessie Love (who would later star in a more significant drug film, Human Wreckage). Alma Rubens, who became a drug addict in real life, also played in it. Intended as a parody of Sherlock Holmes, with Fairbanks playing a crackpot detective called Coke Ennyday, it resembled nothing so much as a home movie shot in the style of Mack Sennett. What makes it of interest today is the fact that anyone could find anything funny in the subject of drug addiction. Coke Ennyday injects himself frequently and literally vibrates with glee. Fairbanks was hyperactive anyway; D. W. Griffith thought him afflicted with St. Vitus’s dance and felt he belonged at Keystone. This picture looks like some kind of awful revenge, for it was released as a two-reeler under the Keystone brand. Surprisingly, it was made twice—once by William Christy Cabanne, who was fired, and then by John Emerson, who reshot the entire picture with assistance from Tod Browning.27 Anita Loos wrote the titles.

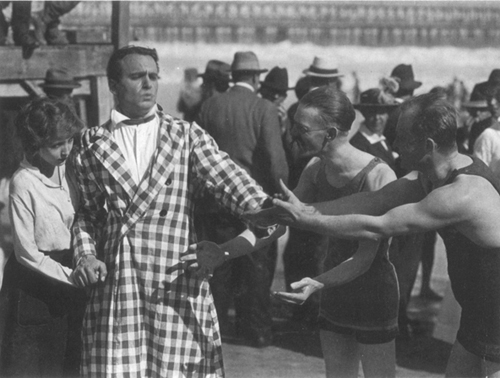

Mystery of the Leaping Fish, 1916. Gag shot with Douglas Fairbanks as Coke Ennyday, a cocaine-addicted parody of Sherlock Holmes, and Bessie Love. On the right, the McCarthy brothers, who devised the “flying fish.”

The story revolves around a plot to smuggle drugs into the country hidden inside inflatable rubber fish. The special-effects man, J. P. McCarthy, had invented six-foot-long fish with rubber fins which could be used by bathers for floating, sitting, or swimming. (The idea was decades ahead of its time—at least McCarthy and his brother had the foresight to patent it.)

Douglas Fairbanks disliked the picture so much he tried to have it withdrawn, and one can only sympathize with him.

“The film’s basic idea is confused,” wrote Arthur Lennig. “Ennyday (an addict) prevents illegal importation of the very thing which he is addicted to. If this inconsistency is supposed to be ironic or humorous, the effect does not succeed.”28

Fine Arts was one apex of the Triangle Film Corporation; another was Kay-Bee, managed by Thomas Ince, whose contribution to the drug controversy was The Dividend (1916). Written by C. Gardner Sullivan and directed by Walter Edwards, it starred Charles Ray, revered for his performance in the Civil War drama The Coward. Variety thought his playing in The Dividend far superior and stamped it as the highest kind of screen art.

“John Steele (William H. Thompson) is head of a large realty corporation who squeezes his poor tenants and cuts wages in his factory. He is a widower with an only son (Charles Ray), but is too busy even to attend his boy’s graduation. The boy comes home and asks his father for a job. Steele scoffs and offers him $3.00 a week to sweep out the office. The boy is serious-minded and argues that with his education he is entitled to a better opportunity. Steele hands him a check and laughingly tells him to go out and play. While out doing the town one night, the youngster visits an opium joint and becomes addicted. When Steele finds out, he throws his son out of the house.

“ ‘If you had been a real father to me I wouldn’t have become a dope fiend. Did you ever give me any encouragement?’ ”29

The father, obsessed with his business, continues to accumulate wealth. But there comes a time when he yearns to see his son, and his wish is granted in the grimmest fashion—the boy is brought home after a street brawl, a hopeless wreck. He eventually dies.

“The scene between father and son as the boy regains consciousness and finds himself in his father’s arms will bring a lump into the throat of a mummy,” said Variety.30

Said the New York Dramatic Mirror: “The idea of the millionaire building a mission to salve his conscience, and his heavenly attitude when he is to speak at the opening of it, does much to give irony to the picture, and it has been so well directed that this and other big scenes of dramatic character at most eclipse the somewhat disgusting details of the gutter.”31

Drugs produce hallucinations; perhaps the men who made films about them should have tried some. Harry Pollard demonstrated a degree of cinematic flair in his The Devil’s Assistant (1917), which featured his wife, Margarita Fischer, but when it came to the allegorical scenes his imagination deserted him. Written by J. Edward Hungerford, the film laid great store by its hallucinations, or visions as they were usually called in pictures. But instead of the bizarre and surreal landscape of dreams, Pollard evokes only stock-company scenery for his images of Hell.

Charles Ray and Ethel Ullman in The Dividend, 1916. (National Film Archive)

It is night and a storm breaks out, the lightning achieved by the simple expedient of scratching on the negative. But now something fresh; a car bounces toward us, its headlights glaring, the rain streaming past the light in silver rivulets. As the car passes the camera, the heavy cable supplying the arc lights in the headlamps can be seen trailing behind it. Never mind; the next scene, in a wayside shack, is lit by the headlights. A black chauffeur watches the attempted seduction of Miss Fischer by an evil doctor (Monroe Salisbury), a drug pusher. When she realizes his intentions, she throws a candle at him. The darkness returns and the scene is lit by lightning flashes, and we can see the doctor advancing, the girl holding a chair—a fight—the flashing almost fast enough to induce hallucinations on its own. At length, a thunderbolt hits the shack and the roof collapses. A skeleton on horseback gathers up the girl and rides through the night sky. A bearded boatman rows them across the Styx, where stray souls struggle in the fog-shrouded water. Cerberus, the three-headed dog, guards the gates to Hades. “Out of the Abyss of Darkness comes the Promising Light of Hope,” as the girl is rescued and she and her husband (Jack Mower) pose against the rising sun as they depart to start life anew.

“As soon as this thing started,” wrote Wid Gunning, “it was painfully obvious that we were in for five reels of tortured heroine, and, believe me, we got it with all the frills.” He warned that audiences were liable to find it excruciatingly funny, especially the director’s conception of Hell. “Along with other weird things, he had a big dog with a couple of bum heads hung on either side of his real head, and—oh boy!—if they don’t get a laugh it’ll be because no one in your community has a sense of humor.”32

Such films feared to tell the truth about the drug traffic. One film which made a valiant effort in this direction was A Romance of the Underworld (1918), Frank A. Keeney’s first venture into production. It was essentially a melodrama about a girl fresh from the convent who joins her brother on the Lower East Side. A young reform lawyer opens an investigation which reveals that the brother is the lieutenant of a notorious drug trafficker. The story was based on a 1911 play by Paul Armstrong, who also wrote The Escape,33 and the film was shot on location in the streets of the Lower East Side, in Chinatown, and at the Tombs prison with its Bridge of Sighs. It was directed by James Kirkwood.

The film was taken to Sing Sing and shown to the inmates, who applauded it warmly. A review written by a prisoner indicates how close this lost picture came to suggesting the involvement of municipal politicians in the drug traffic: “The two greatest evils in the world today are Prussian ‘kultur’ and the ‘dope’ habit, and although the former sooner or later will surely be crushed, the latter will continue to wreck the minds and bodies of men and kill their souls just as long as drugs can be obtained in an unlawful manner. The theme … portrays in a vivid manner the power of the ward ‘Boss’ that makes possible the existence of this horrible menace.”

Frank Keeney said he valued this review more than any other. “If such an audience cannot size this picture up at its true worth, no audience can.”34

The Devil’s Assistant, 1917. Margarita Fischer as a woman addicted to drugs after the loss of her baby. (Wichita State University Library)

The drug-film cycle came to an end about this time, when, with America at war, such critical subjects were felt to be unpatriotic. In 1918, narcotics clinics were opened to ensure addicts a steady supply under medical supervision and to wipe out drug peddling. In New York, on some days, the lines of addicts extended for several city blocks. Newspapers wrote sensational reports, public opinion was outraged, and the moral police rose up to seal the doom of the clinics.

In December 1914, President Woodrow Wilson had signed the Harrison Narcotic Act, which specified that everyone involved in narcotic transactions, except the customers, had to register with the government. In 1919, a Supreme Court decision exploded like a time bomb, revealing an aspect of the act few had taken seriously: the provision that unregistered persons could purchase drugs only upon a doctor’s prescription and that that prescription had to be for legitimate medical use. The provision destroyed what peace of mind remained to most addicts, among whom were many casualties of war.

“As a direct consequence of [the act], the medical profession abandoned the drug addict,” wrote Troy Duster.35 Doctors who continued to prescribe were arrested, prosecuted, fined, or imprisoned. The addict, isolated from legal sources, was forced to turn to the underworld.

The same year, the Volstead Act outlawed drugs as well as alcohol. The narcotics clinics were closed between 1920 and 1922, and the number of arrests for narcotic offenses rose from 888 in 1918 to 10,297 in 1925.36 In 1922, the Jones-Miller Act established a Narcotics Control Board and a five-year sentence for pushers.37 And such drug films as reached the public screens were invariably condemned for “educating” an innocent public.38 Heroin, easily prepared and transported, leaped into prominence on the black market. By 1929, it was estimated there were between 1 and 4 million addicts consuming $5 million worth of drugs annually.39

“The American problem” was now out of control. It had already begun to take its toll of the motion picture industry itself.

HUMAN WRECKAGE Dedicated to the memory of “A MAN who fought the leering curse of powdered death and, dying, was victorious,” Human Wreckage was made as a direct result of the Wallace Reid case.

Wallace Reid was the son of playwright and film director Hal Reid, who died less than three years before him. He was on the stage with his parents at the age of four, although he was later sent away to prep school. Good-looking, with an easy charm, he was talented in many areas. He was well-read, eager, and energetic. But he remained a dilettante; he painted in oils (adequately), he wrote poetry (which he showed to very few), he studied chemistry (for a while), and he played (quite well) a number of musical instruments. Acting was at the end of his list of accomplishments, and, while he enjoyed it, he was not particularly interested in it. He was far more enthusiastic about directing. In the early days, he was able to combine scriptwriting and directing with acting, but soon he was such a favorite with audiences that he was forced to concentrate on acting. “I’m looking forward to the day when I’m fat, forty and directing,” he used to say.40

So popular was Reid as the jaunty, sporting young American that Famous Players–Lasky rushed him from picture to picture—many of them cheaply made—and he turned out more films in the last two years of his life than any other male star.41 It was almost as if the front office knew the end was at hand.

Reid was the kind of young man immortalized by F. Scott Fitzgerald. He should have had a large house on Long Island and unlimited leisure. Yet when he first came into pictures, in 1910, he was known as the most industrious person on the lot, practicing with cameras, working on scripts, performing stunts, until he was as much of an all-rounder with film as on the sports field.

According to his friends, his greatest weakness was his unfailing good nature. He was unusually generous, giving away much of the money he had earned, helping people in trouble. He was essentially a child, fascinated by toys such as motorcars and forgetting appointments if he became involved in something more interesting. He was the life of the party, even if it meant staying up until five, with a hard day ahead, because he could not bring himself to ask his guests to leave.

“They would laugh at you if you told them I ever had a serious thought,” Reid told Herbert Howe, “but just between you and me I’d like to do something worthwhile some day—give something to the world beside my face and figure.”42

He liked motion picture work, but detested the parts he was assigned by Famous Players. He wanted something more demanding. According to cameraman Percy Hilburn, he grew bored and listless, neglecting his real talent;43 but this may have been the effect of his addiction.

Precisely how Reid became addicted is hard to ascertain. Close friends remained guarded. “I shall not attempt,” said one, “to tell when and why Wally started on his fatal journey. A number of circumstances brought about his trouble.”44 Later, an explanation surfaced which was so straightforward one wonders why it was not in circulation at the time of his death. On location in the High Sierras for Valley of the Giants (1919), the company train was wrecked and Reid was injured. Nevertheless, he assisted in the rescue operation and was the last to receive medical attention. Thereafter, he suffered from blinding headaches, and his back also hurt. A doctor gave him morphine. He was confined to bed for three months, the morphine continued, and he became an addict.

The only thing wrong with this story is the bit about Reid as hero. Alice Terry, who as Alice Taafe worked on the picture, remembered the accident and an account that appeared in such newspapers as the Los Angeles Herald.45 It was nearly fatal—a caboose full of people somersaulted down an embankment—and a number of the cast and crew were injured. Reid was badly cut in the back of the neck. Said Alice Terry, “They gave him veronal in milk so he could sleep, because he was quite badly hurt and had a lot of stitches. After that picture, I heard he was still taking it, and then of course.…46

Reid’s wife acknowledged the accident and admitted that he had been given morphine, but she denied that he then became an addict. This did not occur, she said, until 1921, when he went to New York to make Peter Ibbetson (released as Forever), the most difficult role of his career. He fell ill, and when he realized the extent to which he was delaying the production and adding to the cost, he became worried. “It was his grim determination and his good nature which prompted him on. To nerve him for his daily and arduous task, the New York physician gave him morphine.”47

Mrs. Reid’s insistence that he was given morphine not in Hollywood but in New York arouses one’s suspicions. Was this something she agreed upon with Hays and the studio heads? Pinning the “blame” on an anonymous New York physician would deflect it from the studio doctor.

Karl Brown, a cameraman on other Reid vehicles, had no doubt of the studio’s involvement: “The picture was nearly finished, but there was no way of shooting around Wally. He just had to be had. So the company, not wanting to lose the investment entirely, sent a doctor with an ample supply of morphine to the location, where he injected Wally to the extent that he could feel no pain whatsoever and he was able to finish the picture. But after the picture was over Wallace Reid was thoroughly hooked on morphine. Normally, he could have been sent to a sanitarium. But he was altogether too good box office, there was too much to be gotten out of Wallace Reid. So in order to keep the services of this most popular of popular leading men, the studio kept him supplied with more and more morphine.”48

Brown explained the role of the studio doctor: “He goes where he’s told, he does what he’s told. At the moment he enters a studio, which is in effect a small principality with the vice president in charge of production being the prince, whatever is required of him he does. Now that means everything from an injection of a forbidden drug to an abortion and all things in between.”49

Mrs. Reid’s insistence that her husband’s addiction did not begin until Peter Ibbetson fails to take into account the rumors that were already in print by the time of the film’s release. Variety, in September 1921, reported that the wife of one of the most popular of the younger male stars had time and again had the peddlers of dope who were supplying her husband arrested, but she had been unable to get him to kick the habit.50 A confidential report issued in 1921 by the Los Angeles County marshal stated that within a short time a whole new crop of picture favorites would be necessary because of the prevalence of drug addiction among the current stars.

According to his widow, Reid began to use liquor as a cover for the drugs. Eventually he confessed to her that he was a morphine addict. He was determined to fight it, but his easygoing personality had altered and he became more and more difficult. According to Douglas Whitton, he blackmailed directors into bribing him—sometimes a thousand dollars a day—to get him on the set.51 He flaunted his habit, showing director James Cruze a trick golf club with a hypodermic syringe in the handle. (This would have intrigued Cruze, soon to be addicted himself.)

Wallace Reid pictures continued to be released, but the fans noticed that his eyes looked tired and that his old spontaneous manner had gone. They wrote letters about him to the fan magazines: “Snap out of it, Wally!” they demanded.52

During the making of Thirty Days, he collapsed. Famous Players–Lasky had survived the Arbuckle and Taylor scandals, although Arbuckle had cost them an estimated million dollars in lost revenue. Reid, the company’s top star, would represent another two million down the drain if his films were banned by Hays. The studio presented Reid with an ultimatum: kick the habit or face the consequences.

Reid went into a sanitarium, telling Cecil B. DeMille, “I’ll either come out cured or I won’t come out.”53 By arrangement with Hays, Mrs. Reid helped to defuse the situation by holding a press conference at her home and taking the reporters into her confidence. They responded by treating the case with compassion. The Los Angeles Examiner, presumably on Mr. Hearst’s orders, printed a special copy for delivery to Reid with the news of his struggle omitted. Photo-play told its readers that he was suffering from Klieg eyes and a serious nervous breakdown.54

Reid appeared to be winning his fight, but after he had reported back for work, an intestinal disturbance developed which baffled his doctors. Every test known to medical science was tried. “Needles half a dozen inches long were driven into his spine,” said Mrs. Reid. “The pain he endured was terrible.… Not a single test showed a positive result.”55 On top of all this, the complete withdrawal of morphine had affected his metabolism. He caught influenza; like an AIDS victim of today, he had no resistance. He died on January 18, 1923, at the age of thirty-one.

As Reid’s body lay in state, traffic was held up for blocks; thousands jostled for a final look. The streets were packed along the route of the funeral procession and the church was filled with flowers.

The papers dropped the matter, and Variety wondered why: “The exploitation of Reid’s death would have been the best weapon Fate has ever put into the hands of publicists against the drug habit. The death of one of the most notable screen stars is a terrific object lesson. It will do more to break the drug traffic than all the warnings from pulpits or lecture platforms that could be delivered in a generation by reformers whose exposes are scarcely more free from self-interest than the newspapers.”56

Mrs. Reid was grief-stricken and exhausted, and she simply wanted to retreat from the public eye. “I am very, very, very tired.” she said. “For two years I have waged my own little battle against this thing alone and too often in the darkness of ignorance … But during these days since my husband’s going, my home has been flooded with appeals to me to do something. ‘They will listen to you. They loved Wally and they admired his brave fight and they hate the thing that killed him. Tell what you know for the good of humanity.’ ”57

Mrs. Reid, with Adela Rogers St. Johns, attended a conference on narcotics in Washington, and on her return to Hollywood set to work on a drug-propaganda film, in collaboration with Thomas H. Ince. It has been said that Ince produced the film out of kindness to Mrs. Reid, but producers are not noted for kindness. In any case, Mrs. Reid is on record as saying it was not her idea. Will Hays gave special dispensation for the film, which violated most censorship codes, to be produced under the sponsorship of the Los Angeles Anti-Narcotic League.

Mrs. Reid selected Bessie Love to play the suicidal addict, Mary. The actress was not exactly thrilled at the prospect—her friends warned her she would be thought of as an addict herself. But Mrs. Reid talked her into it. Bessie Love was quoted at the time, in the stilted phraseology so beloved of publicity departments when striving for dignity: “To fully prepare myself for the role, which first of all entailed a thorough psychological understanding, I availed myself of the friendly offices of a physician.…”

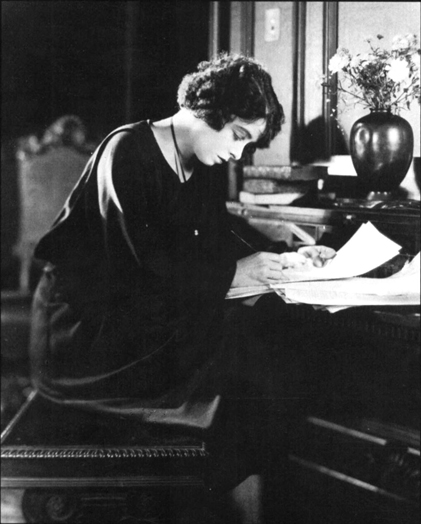

Left: Mrs. Wallace Reid in Human Wreckage, 1923. (National Film Archives) Below: Wallace Reid (right) in William de Mille’s Nice People, 1922. with Conrad Nagel and Bebe Daniels.

Bessie Love did not talk, or write, like that. Over lunch one day in 1978 she told me of her experiences:

“We had a doctor as a technical adviser, and he suggested that he take us down to the jail to meet the real addicts—the women, anyway. I went thinking I must do my duty, all buttoned up. I never had so much fun in my life. Oh, I had a ball. There were a few really distressed women—but the others! They were such fun. One girl showed me how to do it. She took me behind a door—she was very modest—and she showed me how she was punctured all over. She’d run out of places to stick a needle.

“They thought I was a nurse; I wouldn’t have been allowed in otherwise.

“ ‘Did Mrs. Reid go down?’ I asked.

“Bless her heart, she didn’t have to.”58

Bessie Love received a letter in the early 1970s from a man who had played her baby in the picture. By an extraordinary coincidence, he had grown up to become a narcotics agent.

James Kirkwood, who played the doctor, resigned from the cast of the stage play The Fool in New York after being advised by clergymen that he would be accomplishing a bigger work were he to undertake the lead in the film.59

Something of what Mrs. Reid had gone through was incorporated into the story, and while MacFarland, the character played by Kirkwood is an older, more dedicated man than Reid, much that happened to Reid happens to him—although, as Mrs. Reid was at pains to point out, her husband never had to obtain his morphine from the underworld: “His source was neither illicit nor illegal—it didn’t have to be. Wally could charm any doctor into giving him the tablets he wanted. He knew just enough about medicine to convince doctors that he knew exactly how many grams he could safely take every day.”60 And he had constant and unfettered access to the studio doctor at Famous Players–Lasky.

Whatever the merit of the final result, it was courageous of Mrs. Reid to work on the film in any capacity; to agree to act in it was positively heroic, for it brought her into direct contact with scenes which must have chilled her. Ironically, the character she plays overcomes her husband’s addiction by a ruse—by her own skill as an actress—and the story ends with a victory to compensate for all the defeats.

D. H. L. Kirby, former executive secretary of the China Club in Seattle, who had just completed a national anti-narcotics crusade, assisted Mrs. Reid,61 and the picture featured a number of prominent people: Mayor George B. Cryer of Los Angeles and Chief of Police Louis D. Oaks—both members of the Anti-Narcotic League—appeared in small roles, along with Dr. Rufus von Kleinsmid, President of the University of Southern California, and Judge Benjamin Bledsoe.62

Shooting the final sequence, the wild taxi ride in the streets of Los Angeles, required police cooperation. Cameras were set up on top of vehicles and on the back of a police car which went through the streets with its siren wide open. An event occurred which even at the time, Photoplay admitted, sounded like something from the fertile brain of a press agent: “As the whistles blew and the camera began to grind, a Chinaman started across the street, evidently quite unconscious of what was happening around him. Two policeman started toward him, anxious to get him out of the path of the taxi. But the Chinaman misunderstood. With a terrified glance at the two officers, he dropped something from the sleeve of his jacket and, slipping into the crowd of bystanders, disappeared. The scene was shot before one of the policemen noticed the little package the Chinaman had dropped. Picking it up he found that it was filled with little ‘bindles’ of cocaine.”63

Human Wreckage is in the vanguard of the legion of lost films. It is therefore of particular importance to provide details of the story. My source is the script, by C. Gardner Sullivan, first entitled “Dope” and then “The Living Dead.”

“The Dope Ring,” declares the prologue, “one of the most powerful and vicious organizations in American history, is composed of rings within rings, the inner ring undoubtedly including men powerful in finance, politics and society. But the trail to the ‘men higher up’ is cunningly covered. No investigator has penetrated to the inner circle.”

The picture fades in to an Indian poppy field. The poppies are nodding in the breeze, and the gray, wasted faces of addicts are faded into them. Mrs. Wallace Reid delivers a statement, in the company of her two children: “The drug evil is daily devastating more homes than the white plague [tuberculosis]. None of us can render a greater service to humanity.”

A brief visual sketch of a great city gives way to a bird’s-eye view over which is superimposed the symbol of the drug menace, a hyena.

“Ambitious, unafraid, seemingly unconquerable, but bleeding in secret from the fangs of THE BEAST.”

Dope pushers are characterized not only as furtive men or flashy gangsters, but also as elegantly dressed women. Peddlers are shown to be particularly active around high schools, in the slums, and on the smuggling routes from Canada to Mexico.

Jimmy Brown (George Hackathorne), a frail, likable twenty-year-old, has been a heroin addict for a year. He sniffs a dose and gains the confidence to snatch a watch from a pawnshop. He runs straight into an old friend, Ginger (Lucille Ricksen), who grabs hold of him. She defends him against the police, but they haul him off.

His mother, Mrs. Brown (Claire McDowell),64 a faded woman of forty-five, is visited by the police at her shabby tenement and told the news. A neighbor, Mother Finnegan (Victory Bateman), senses something is wrong. She lives with her daughter, Mary (Bessie Love), who has a baby of six months. Mother Finnegan tells Mrs. Brown not to cry: “I’ll take you to see Mrs. Alan MacFarland.”

Ethel MacFarland (Mrs. Wallace Reid), wife of a famous attorney, devotes much of her time to helping those less fortunate than herself. When Mrs. Brown is brought to her, she listens with sympathy and persuades her husband to take the case.

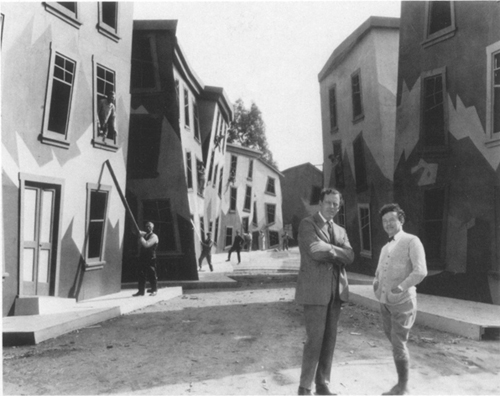

James Kirkwood stands with director John Griffith Wray on a set inspired by Caligari—the view of a drug addict—for Human Wreckage, 1923.

Alan MacFarland (James Kirkwood) is shocked at the idea of a twenty-year-old addict: “It’s a disgrace to the state,” he says. At Jimmy’s trial, MacFarland insists he is not guilty. “Why? Because he was under the influence of a powerful drug and was not morally responsible.”

There is a cut to a grotesque street—“something on the order of Dr. Caligari’s Cabinet” specified the script—with the houses set at insane angles. Down the street prowls the hyena.

MacFarland wins his case, and Jimmy is sent to the narcotics ward of the county hospital: “Great types to be picked here; we should get the real thing so far as possible.” Jimmy is put through the first stage of the cure—deprivation. He suffers agony, but tries to take his punishment cheerfully. His mother is warned that the real danger lies ahead, when he leaves the hospital, becoming easy bait for the dope peddlers.

MacFarland, driving himself beyond endurance on another case, is offered something to keep him going by a fellow club member, Dr. Hillman (Robert McKim)—morphine. “No,” says MacFarland in disgust. “The cure is worse than the disease.”

“I use morphine at times,” says Hillman mildly. “Do I look like a dope fiend?” MacFarland submits. “Once can’t do me any harm.” But once is not enough, and soon he awaits the regular visits of the drug peddler.

His wife, visiting the Browns, notices a curious thing: Mary Finnegan slips into her bedroom; the door does not quite shut, and, through a mirror, Ethel sees Mary injecting herself. As if this were not shocking enough, she does something else.

Bessie Love as the drug-addicted mother in Human Wreckage, 1923, produced by Mrs. Wallace Reid and directed by John Griffith Wray for Thomas Ince.

“This scene,” says the script, “will have to be taken with extreme care. The reflection of Mary includes her head and body down to her waist. Taking a small bit of morphine from the same bottle from which she filled the needle, she dilutes it in a glass of water. Opening her dress she dips her fingers into the weakened morphine solution and rubs it on her breast. Although this scene must be handled with extreme delicacy there should be no doubt as to what Mary is doing. She has gotten into the habit of rubbing morphine on her breasts to quiet the baby when he nurses.”65

Ethel cries out, rushes across the room, and snatches the baby from Mary’s arms. Remorse overwhelms the girl. The revulsion in Ethel’s face is too much for her to bear, and, crying “I know I am worse than a murderess,” she tries to kill herself by jumping from the window. Ethel seizes her and drags her back.

Mary is taken to a private hospital and separated from her child.

Mary’s pusher, Harris (Otto Hoffman), is arrested by the Federal Narcotic Squad, and because he is high on cocaine himself, they manage to trick him into giving them the names of other drug peddlers. MacFarland’s dealer, Steve Stone (Harry Northup), is the next to be picked up. But he has influence, as he is the supplier to all the best people. A title—“Higher up”—introduces the luxurious headquarters of a wealthy and powerful group. The men keep their backs to the camera, and we never see their faces. Orders are issued: “Furnish bail for Stone immediately—then have him see the best lawyer in the city.”

The best lawyer is MacFarland. In no time at all, the newspapers proclaim: STONE “NOT GUILTY” ON DOPE RING CHARGE. Jimmy Brown, now a taxi driver, tells his friends, “Every hophead in town knows that Stone handled dope.” The title “Not guilty” is repeated like a tolling bell before a shot of Mary, suffering in the hospital and before a shot of a peddler selling dope to a girl of sixteen. Even in jail, the drugs circulate smoothly, thanks to the “underground,” and Harris is kept fully supplied. He makes plans to escape.

A package is delivered to MacFarland, a present from a grateful Stone—a bottle of morphine. His battle with himself is now reaching a crisis. He does his best to suppress the craving, but once he has injected himself he feels a wonderful sense of relief.

Ethel discovers him in an unnatural sleep, and finds the needle and bottle. She is filled with despair.

Harris escapes, and an accomplice slips him a gun. He shoots a policeman and also a bystander by mistake before he is gunned down.

Ethel decides the only thing to do with MacFarland is to take him to a cottage on the seacoast where no drug peddler can reach him. MacFarland cooperates with Ethel in her struggle, but his desire is too strong. Denied a needle, he drinks the morphine right from the bottle. When Ethel discovers this, she gives up. MacFarland is shaken to discover that his wife has all the symptoms of addiction herself.

“I am so tired and I can’t sleep,” she says. “I envied you last night.”

Her husband is appalled. “Ethel, dear, I am not worth saving, but you are.”

In desperation, he searches for a bottle he knows she had hidden and at last experiences something of what he has put his wife through. He forces himself to destroy the morphine and to give up the habit once and for all.

The doctor arrives, and Ethel says, “Thank God, I don’t think we will need you.” And she explains how she tricked her husband: “He couldn’t conquer for himself, but he has conquered for me!”

Now the city opens its war on the drug ring. As Ginger says, “It’s about time, for the love of Mike!” Dr. Hillman, the dope doctor, is arrested. The men higher up put out the word to MacFarland to stop this crusade, and Stone calls to deliver the message: “Don’t forget we can ruin you!”

MacFarland makes an idealistic statement: “The American public no longer regards the drug addict as a criminal, but as a sick person needing the best medical attention obtainable.”

Jimmy Brown picks Stone up in his taxi and takes him on a wild, drug-induced ride through city traffic. “You’re on your way to hell,” he tells him, moments before he drives at full speed into a locomotive. Both are killed.

MacFarland writes another statement, which belies the first: “If we are to crush the drug evil, we must have a law which will bite. It cannot be too drastic.”

And at the finale, Mrs. Wallace Reid reappears to ask: “Won’t you help us?”

An epilogue was originally planned, to be set in the Federal Hospital for Drug Addicts at San Clemente, California. The script specified:

“An imaginary view of buildings and pleasant grounds.

ONE WAY OF HELPING THE DRUG ADDICTS—A GOVERNMENT HOSPITAL TO BE ESTABLISHED ON SAN CLEMENTE ISLAND OFF CATALINA, WHERE ADDICTS COULD BE GIVEN THE PROPER ATTENTION AND GUARDED AGAINST DOPE-PEDDLERS.”

We were to be shown modern wards, and addicts on the road to recovery, looking forward to a new and useful life.

The scene was deleted from the script, just as the scheme was scrapped in reality. The island was used for target practice by the marines instead.

Much of the critical reaction to the film fulfilled Mrs. Reid’s highest hopes. The reviewers were a hard-bitten lot and would not have praised it out of mere sympathy for her plight. Variety’s man, Sime Silverman, certainly spared her nothing: “Human Wreckage is strictly a commercially made drug expose film. Like many others preceding it, there is no merit to any part, from story to acting. As an educator for the purpose of suppressing the drug habit, Human Wreckage isn’t. It is more of an enlightener. The young can see here things they should not know.”66

The other reviewers were almost unanimous in their praise. Motion Picture Classic said: “Human Wreckage is a profoundly moving picture handled with dignity and restraint. There is nothing cheap or sensational about it. Quite the contrary. A tremendous and unmistakable sincerity animates everyone who had anything to do with it. It is a grim, terrific, tragic indictment of stupidity and criminal indifference toward these ‘living dead’ whose pitiable army is vaster than you or I ever dreamed of.”67

On the opening night in New York, June 1923, the entrance to the Lyric Theatre was choked with people. One reporter admitted to being there out of curiosity, doubting the motives, not to mention the taste, of the film. That reporter became an instant convert: “No one could impugn the motives of Mrs. Reid if they had seen her standing up in a box, after the picture, while flowers in gracious tribute were laid at her feet; standing there white faced and weary-eyed, the tears rolling down her cheeks, very near to collapse, a tragic, pitiful, inarticulate figure.”68

In Los Angeles, crowds stormed the doors of the Rialto and hundreds had to be turned away on the first night. The picture was one of the financial hits of the year. The Los Angeles Examiner, engaged in the Hearst anti-drug campaign, called it “the most important picture ever made.”69

The film was not shown in England: “Few films the examiners have seen are more dangerous than this.”70 But it made money for Thomas Ince, and enough to enable Mrs. Reid to take care of her family, set up her own production company, and further her work for the Wallace Reid Foundation Sanitarium in the Santa Monica Mountains. She continued to make personal appearances with the picture and to speak to women’s clubs and other influential groups. She asked them not to think of drug addicts as strange and curious beings but as sick people who could be helped. And she urged that terms like “hophead” and “dope fiend” be dropped.

Wallace Reid would have been proud of her. “If I had known a year ago what I know today,” she said, “my history might have been very different.”71

THE GREATEST MENACE Released before Human Wreckage, The Greatest Menace might prove equally important—if only it could be found. An independent production, written and directed by Al Rogell, it was not approved by the Hays Office. Rogell had read the many reports of drug cases in the papers, and he knew two addicts. “It was a popular subject,” he said. “It was being discussed and yet it was kind of hushed up. It was a terrible thing which America recognized. I needed something to write, something to promote. I made it up as I went along.”72

He wrote an outline and contacted Mrs. Angela C. Kaufman, a wealthy philanthropist deeply committed to the fight against addiction who was known as “the angel of the county jail.” “She had gone down to the jail on behalf of the prisoners innumerable times,” said Rogell. “She thought the picture was a wonderful idea. She got together her spiritualist group and agreed to put up the money—not very much for a picture, around $20,000.”73

Rogell spent a lot of time with Mrs. Kaufman in the company of addicts at the county jail. And for three days he lived in a cell, dressed as a convict, observing two men who were trying to kick the habit. “They thought I was just another inmate,” he recalls.

Angela Kaufman was credited with the story, in which Charles Wright, Jr. (Robert Gordon), the son of a district attorney, determines to write about life as it really is. He ignores the warnings of his lawyer sister, Velma (Ann Little), and visits the haunts of drug addicts. A girl who works for the drug ring encourages him to sample narcotics, and soon he is addicted himself. When the girl dies, Charles is arrested for her murder; unaware of his identity, Velma and her father intend to prosecute. But when she learns who he is, Velma defends him and wins the case, and Charles is reunited with his family.74

Rogell previewed the picture at the Ambassador Hotel on January 18, 1923. “They had a theatre there. I’ll never forget coming out and newsboys were shouting that Wallace Reid had died. I was just getting into my car when a fellow came up and handed me a card and said, ‘This man wants to see you.’ The card said Louis B. Mayer. It turned out it wasn’t Louis B. but Jerry G. Mayer, his brother, who had a little exchange downtown. He convinced me he knew all the angles.

“I also got a call from Thomas Ince. He wanted me to send the picture out. He didn’t think I’d bring it myself; I was the producer. But I took it out myself, took it to the projection room and watched it. Ince and two or three of his cohorts were down below. And in those days, the sound of the projector didn’t bother you; you could open up the trap. Between reels, Ince said, ‘Hold it a minute.’ So the operator stopped and I listened, and he was talking to the boys. His plan was to keep me interested and hold up my release—to get out a picture written by Wallace Reid’s wife, Dorothy Davenport, who was also in the room. I didn’t know what to do. I just grabbed the film and then I called this fellow, who was supposed to be Louis Mayer. He told me what a great man he was and what he could do, so we set off for New York—Mrs. Kaufman wouldn’t let him take the picture without me. While we were on the train, Ince came out with the ads for the Mrs. Wallace Reid Special. We were now second-best. Mayer turned the film over to a company called Asher, Small and Rogers, and they distributed the picture, states rights. It did fairly well and Mrs. Kaufman was pleased. They kept most of the money. We got back a few thousand, but not enough to cover the cost of production. And I didn’t get paid—I had a piece of the picture instead.”75

The film was released a month before Human Wreckage, in May 1923. No reviews appeared in Variety or Photoplay. “That could have had something to do with Ince,” said Rogell. “He was a very powerful man. And I remember when I saw Human Wreckage, I was infuriated at the ideas he’d taken from me.”76

THE PACE THAT KILLS In the twenties, films about drug addiction had to be morality plays of Old Testament intensity to get by the censors. Yet The Pace That Kills (1928), for all its moralizing, is at times nearer to an instructional documentary. One sequence actually shows the preparation of the potions. Another portrays a method of peddling drugs. The ending is heavy with self-sacrifice and suicide, but for a few reels the place of drugs in society is vividly explained. Thus, The Pace That Kills is a social film of no mean value.

What mars it is the performance of the leading man. Owen Gorin was chosen for the part of Eddie presumably because of his weak but good-looking face. Once he has caked it in make-up, however, he acts as if his eyes were fried eggs. All sense of conviction flies out the window, as Gorin himself nearly does, so wildly do his arms gyrate. Virginia Roye, by contrast, is first-rate; as his girlfriend, she has something of the energy of Clara Bow.

Once again, the city is shown as a place of moral destruction, which has already sucked Eddie’s sister into its maw. Eddie sets out to search for her, saying farewell to his simple country folks. The transition from farmland to town is managed with admirable economy: from the wheel of a car we dissolve to the pistons of a locomotive and to the bogies of a streetcar. Eddie gets a job in a department store, where Fanny (Roye), a sexy shopgirl, takes an instant fancy to him. Eddie’s first busy day exhausts him, and he complains of a headache. Fanny has the remedy. Her expressive eyes dart from one side to the other, and, as the coast is clear, she pulls up her skirt and from beneath her rolled stocking discloses a small packet containing white powder. When Fanny shows him the technique of cocaine sniffing—exactly that used in an earlier century for snuff—she turns her back on the camera. But it is obvious what she is doing. And Eddie’s sudden return to health must rank among the cinema’s more embarrassing moments.

Fanny takes Eddie to a nightclub, he anxiously watching the taxi meter as the fare rises like the National Debt. In the cabaret (the one expensive set in the picture), Eddie discovers his sister is now a gangster’s moll. She spurns him.

A few scenes later, Fanny takes Eddie to a party. Opening on the legs of girls dancing the Charleston, we mix to an establishing shot before cutting to the pianist. He is sluggish. The same condition affects many of the guests, but it is dispelled by the arrival of Snowy the Peddler (“Arch Fiend of Humanity”). The guests crush round him—“A bunch of ‘Snow Birds’ with their ‘Happy Dust’ and ‘Joy Powder.’ ” The pianist feels much better, and the music begins again, hotter and faster to judge by the dancing. That drugs are a prologue to further licentious-ness is indicated by couples going off by themselves to spacious sofas in dark corners, switching out the light. Fanny smokes a reefer, which she shares with Eddie.

“Soon, all sense of honor and decency lost, the addict will do anything to get dope.” Both are fired for pilfering, and they move in together in a rundown boarding house. They need money to assuage the craving and their harridan of a landlady. In a mirror, we see Fanny taking a shot as a prelude to sex. A symbolic coffee pot boils over.

Next we see the various drugs and their method of preparation … morphine … opium, “which dulls the sharp ache of living for a while—rots the moral fiber” (the film lays the entire responsibility for opium on the Chinese population)… and finally heroin.

Now Fanny is forced to get money by the only method left open to her. She powders her face to hide the shadows under her eyes and takes up her position in a doorway. She returns to Eddie, shaken but successful. Eddie is not so far gone that he cannot guess where she’s been.

To ease his incessant craving, Eddie moves to a Chinese opium den. In bursts his sister, desperate for relief. She is offered opium, but she needs something stronger—heroin. Eddie staggers over to her. “Oh, Eddie,” she gasps, “has it got you too?” A newspaper headline conveniently reveals her plight. She has shot the gangster—we see the event in superimposition—and is on the run. The police burst in and arrest her.

Back at the lodgings, Eddie stares at a photo of his dear sister, who faces death one way or the other. “Eddie,” says Fanny, “we’ve got to go straight, because …”

“God,” says Eddie, “a baby born to a dope fiend and a—”

“Don’t say it, Eddie, don’t say it.” Fanny gives him one last shot to calm his nerves and sits down to write a note. She kisses Eddie, goes down to the harbor, and ends it all. When Eddie hears the news, he staggers down to the pier and follows her into the next world.

The final title urges audiences to support the Porter Bill—“for the segregation and hospitalization of narcotic addicts—the greatest constructive measure ever offered for the abatement of the narcotic evil.”

Like the lawyer in Human Wreckage, Representative Stephen G. Porter, sponsor of the bill, regarded drug addicts as sick people. “You can’t cure a sick person by sending that person to jail,” he declared. (The bill became law on July 1, 1930, four days after Porter’s death.)77 Originally, the film depicted Eddie’s cure—months of misery in the hospital.78

Norton Parker, the director, had worked for Mrs. Wallace Reid as writer on The Earth Woman (1926), and he had recently made another “Awful Warning” picture, The Road to Ruin (see this page). Made by a company outside the jurisdiction of Hays, The Pace That Kills reached the public in a number of states.

“If you can stand the sermon-length opening title,” said Photoplay, “you can probably stand the rest of it. It’s hot propaganda against the narcotic evil, authentic to the point of grotesqueness, and a scientific treatise for lecture rooms, not amusement houses.… Not the least bit entertaining.”79

Parker’s co-director, William O’Connor, remade the picture in 1936. This time, it was banned by Hays.