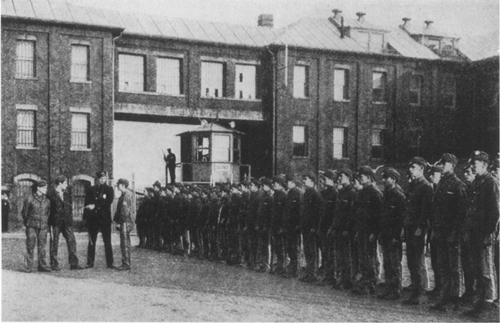

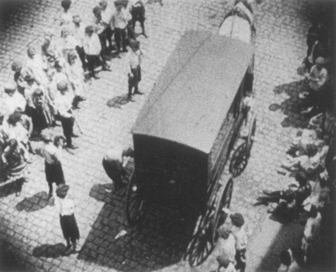

The City of Darkness, 1914. (John E. Allen)

PUBLIC OPINION Trial by newspaper is not a recent phenomenon. It was so common in the early part of the century that a film, Public Opinion (1916), was made on the subject by the Jesse L. Lasky Feature Play Company. Margaret Turnbull wrote the scenario, which was directed by Frank Reicher.1

The opening title read: “In law, the accused is held innocent until proven guilty, but when public opinion is poisoned by yellow journalism, it condemns the accused before the trial begins.” A nurse, Hazel Gray (Blanche Sweet), is employed by a wealthy philanthropist, Mrs. Carson Morgan (Edythe Chapman), whose husband is a doctor (Earle Foxe). This doctor, who had a brief affair with Hazel, is now after his wife’s money. He poisons her and manages to throw the blame on the nurse. The yellow press splashes the case across the front pages, and the girl is condemned before the trial has begun.

One young juryman (Elliott Dexter) is convinced of her innocence and succeeds in persuading the rest to deliver a verdict of not guilty. But public opinion is far from satisfied. The crowd outside the court is convinced she has got away with it because of her good looks. And although the girl is released, the newspapers make her life a misery, and she is ostracized, a fate “almost more terrible than capital punishment.”2

A dope addict shoots the doctor when he refuses him drugs, and the doctor makes a dying confession, which exonerates Hazel. She marries the young juryman, a conventional end to a far from conventional picture.

The strangest comment came from Photoplay, which called the jury “pumpkin headed” for letting the girl off. “Though the woman is innocent, material evidence is against her.” They blamed it on the male jury’s traditional chivalry to the pretty thing, as though “material evidence” was all that counted.3

“While the story of Public Opinion may not be based upon a recent New York murder case,” said the New York Dramatic Mirror, “the resemblance is apparent.”4 Lasky publicity asserted that the big courtroom scene was “an exact replica of that in which the trial was held [and] upon which the story is based.”

Historian J. B. Kaufman has discovered that in September 1915, Dr. Arthur W. Waite of New York married Clara Peck, the daughter of a millionaire drug manufacturer in Michigan. Within six months, he had poisoned both his in-laws and had attempted to murder his wife in the same way. When the police came to arrest him, they found him in a drug-induced stupor. There was no parallel in this case to the Blanche Sweet character. “The closest thing to it was a black maid who testified that she saw Waite put some ‘medicine’ into the father-in-law’s food, and that he tried to bribe her to keep quiet.”5

What is remarkable about the case is that it occurred after Margaret Turnbull’s story was bought by Lasky. It is almost certainly the case referred to by the New York Dramatic Mirror and exploited by the publicity department, but Kaufman can find nothing similar that might have inspired Margaret Turnbull.

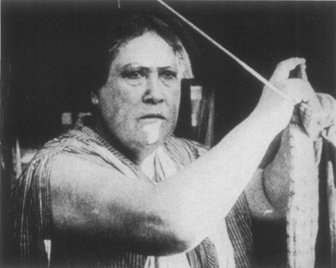

Earle Foxe as the guilty doctor in Public Opinion, 1916, directed by Frank Reicher. (Museum of Modern Art)

Curiously enough, for so intriguing a film, Blanche Sweet had not the slightest memory of having played in it and had to look it up before she could be persuaded that she had.

EVELYN NESBIT America’s most distinguished architect, Stanford White, was shot by millionaire playboy Harry K. Thaw in 1906. This event has a fascination which sets it apart from most crimes passionnels, a fascination revolving around the girl in the case, Evelyn Nesbit. She was only sixteen when raped by Stanford White, “a great man,” in her view, however “perverse and decadent.”6 And she was only twenty when she became involved in “the Crime of the Century.”

The story has so many ramifications into the world of cinema that an entire book could be devoted to them. One of White’s studios, at 540 West Twenty-first Street, New York City, became the headquarters of the Reliance Film Company. Above White’s offices was the workshop of his friend Peter Cooper-Hewitt, whose mercury-vapor lights were so crucial to the motion picture studios. Evelyn—then Florence—Nesbit was sent by White to the DeMille School at Pompton, New Jersey, run by the mother of the future directors. (William was in residence at the time, writing his play Strongheart.) Nesbit was courted by John Barrymore. Thaw’s prosecutor, New York district attorney William Travers Jerome, later raised funds for the Technicolor Corporation. Thaw tried to become a producer in the 1920s and introduced Anita Page to Hollywood.

Evelyn Nesbit in 1902, before the scandal broke. (Ira Resnick)

The case itself had great significance for motion picture history, for it contributed to the beginning of censorship (see this page). And it provided a career for Evelyn Nesbit, thanks less to her talent than to her notoriety.

Evelyn was born at Tarentum, outside Pittsburgh. As a young girl she became an artists’ model and then went on the stage, joining the Floradora company and concealing her true age. When she met Stanford White, a much older man (he was fifty-three when he died), she was touched by his kindly, fatherly interest. He impressed both Evelyn and her mother as someone absolutely safe. On one occasion, her mother went out of town, leaving her in White’s sole guardianship. He gave her champagne, probably drugged, and she felt dizzy and faint. When she came to, she was in bed, naked. “It’s all over,” said White. “Now you belong to me.”7

Harry K. Thaw, a wealthy young man from Pittsburgh, saw her on the stage and bombarded her with letters. When she met him, she was both attracted and repelled. She soon learned that he was a drug addict, an accomplished sadist, and mentally unbalanced. Nevertheless, she felt sorry for him and agreed to marry him. (He was, after all, extremely rich.) When he demanded assurance that she was a virgin, she broke down and told him about Stanford White, a man he hated anyway. Now it was his turn to break down.

Harry and Evelyn were married. On June 25, 1906, they visited Mlle. Champagne at the dining theatre on the Madison Square Garden roof. They thought the show “putrid” and decided to leave. They had reached the elevators when suddenly Thaw ran back, shot Stanford White at point-blank range, and killed him outright. Incarcerated in the Tombs, he explained that his wife had been White’s “sex slave”—that was how the newspapers put it. Thaw made the “unwritten law” plea world famous.

Evelyn Nesbit played her role carefully in the witness box to ensure that Thaw was not sentenced to death. She knew, however, that to avoid a scandal in which they would all be exposed, “the inner circle” had persuaded district attorney William Travers Jerome to have Thaw locked up in an asylum. (They were all members of the conservative Union Club.)

Thaw’s lawyer, Delphin Delmas, persuaded the jury that his client suffered from “dementia Americana” at the moment he shot White—a neurosis, invented for the occasion, for Americans who believed every man’s wife is sacred. After a retrial, the jury obligingly returned a verdict of not guilty on grounds of insanity—and Thaw was sent to Matteawan, the New York State Asylum for the Criminally Insane.8

First to benefit financially from the murder, after the yellow press, was Madison Square Garden itself. The building had been designed by Stanford White, and the roof garden restaurant became more popular than ever as people flocked to stare at the scene of the crime.

To permit people to stare in larger numbers, the subject was hastily put on film. It was ideally suited to satisfy the audience’s scornful curiosity about “the idle rich.” At least one of these films still survives: The Unwritten Law (1907), made by the Philadelphia company, Lubin.9 It is a vivid reenactment, or, as Variety unkindly called it, “a fake.” Harry Thaw leaves the court a free man, which proved the film had been made in a hurry and suggested, too, that audiences expected the verdict to be fixed.

This little picture is as good as a Griffith Biograph in terms of technique and has similar marks of imagination—the vision in the prison, for instance. Painted interiors aside, there is no artifice to spoil the enjoyment. Perhaps Stanford White (here called Black) dies overdramatically, but otherwise the playing is as naturalistic as a documentary. The suggestiveness of the red velvet swing and “the boudoir of a hundred mirrors” must have been potent images for audiences from cold-water flats.

The red velvet swing became so notorious that the phrase passed into the language. (A film about Evelyn Nesbit, on which she served as consultant, was made in 1955 as The Girl in the Red Velvet Swing.) Evelyn testified at the trial that when she was sixteen, she and a friend visited White’s studio on Twenty-fourth Street—the most gorgeous place she had ever seen—and he gave them a tour of the rooms upstairs. In one was a large velvet chair hanging from two ropes: “He would push us until we would swing to the ceiling. There was a big Japanese umbrella on the ceiling, so when he pushed us our feet would crash through.”10

In The Unwritten Law, slightly more sedately, White fastens a parasol to the door, and encourages Evelyn to swing until her feet touch it. (The other girl does not appear.) Later, Evelyn performed the trick in the nude, but of course the film does not hint at that. Instead, it proceeds to the next thrill, the Boudoir of a Hundred Mirrors. In an elaborately painted rococo set, White gives Evelyn the fatal drink. She becomes dizzy, and he places a screen around her. That is all we see. But those familiar with the yellow press could fill in the rest.

In the scene at the Tombs, Evelyn and her mother try to console Thaw. When they leave, he suffers alone, and a vision of the murder appears in the window above him. Actually, Thaw managed to maintain his way of life in prison; his meals came from Delmonico’s, whiskey was smuggled to him, and he continued to play the stock market.11

The print in the National Film Archive is cataloged as featuring Evelyn Nesbit herself, but the girl who appears in it does not resemble her, being a different shape and lacking her beauty. Miss Nesbit was also said to have made her screen debut in The Great Thaw Trial (1907), which, like the Lubin film, covered the main events, but she was not in this one, either. At this stage, she said, she had an aversion to trading on her association with Thaw.12 But Thaw, behind bars, must have been permitted to see the film, because he sent his attorney to the court where a proprietor of a theatre had been charged with imperiling the morals of young boys by showing it. “Mr. Thaw has requested me to inform the court,” the attorney said, “that the moving pictures which have just been under consideration are not what they are purported to be. He wants it distinctly understood that the picture of his wife is not a good one and that the other pictures do not show the marriage ceremony as it occurred, nor the principals in it. The same applies to the tragedy of the roof garden.”13

The Thaw film attracted twice as many spectators as The Life of Christ.14

Evelyn Thaw gave birth to a son, Russell. She declared he was Harry’s child, even though Harry had been locked up for several years. Filing for support, she explained that Harry had bribed a guard at Matteawan to allow her to spend “a heavenly and fruitful night” with him.15 Harry hotly denied this, and Evelyn eventually admitted another prominent man was the father, but she would take the secret of his identity to her grave.16

Evelyn appeared in vaudeville in 1913 at the astonishing salary of $3,500 a week and broke box-office records.17 Harry Thaw helped her box office by escaping from Matteawan, and Evelyn capitalized on that by telling the press of his death list, with her name at the top. Harry was captured in Canada, which guaranteed Evelyn Canadian bookings, and he was then deported to the U.S.

Hal Reid, who produced Harry K. Thaw’s Fight for Freedom (1913), had written and produced a play in which Thaw was portrayed sympathetically. He went to Sherbrooke, Canada, and New Hampshire and talked to Thaw in his cell. The prisoner agreed to be filmed, and Reid photographed 500 feet of him eating, looking out of his cell window, and talking. The promoters, the Canadian-American Feature Company, wanted $1,500 a week for the reel. Several other Thaw films appeared on the market, including one called Harry Thaw’s Escape from Matteawan,18 so Thaw had obligingly sent Reid a telegram from Quebec, which was used in the advertising:

THE ONLY MOVING PICTURE TAKEN OF ME IN MY CELL AT SHERBROOKE OR ANYWHERE UP TO DATE WERE TAKEN BY YOU. I AUTHORIZE YOU IF YOU SO DESIRE WITHOUT COST OR PREJUDICE TO ME TO LEGALLY PUNISH OR ENJOIN ANY AND ALL PERSONS WHO SHOW ANY MOVING PICTURES CLAIMING THEY ARE OF ME INSIDE ANY PRISON.19

Reid’s film was shown on the Keith and Orpheum circuits, although in some cities, such as Spokane, Washington, the censor refused to pass it. And a five-reel feature about Thaw was so badly mauled by the Detroit censor that only the last two reels survived. All the early scenes—the Red Velvet Swing, the murder—were cut.

“The real interest around Thaw,” said Commissioner Gillespie, who ordered the cuts, “is his escape. I think the masses are now in sympathy with him. I can see no objection to pictures of his escape, but nothing previous to that.”20 The newsreels were able to run items on Thaw unmolested.

Hal Reid’s film, elaborated into Escape from the Asylum, “converted many people to the belief that Thaw had been sufficiently punished and that he deserved sympathy.”21

By May 1914, the public’s curiosity having been satisfied, the Evelyn Nesbit Thaw vaudeville show closed. She announced that hereafter she wanted to be known as Evelyn Nesbit, and she formed her own company.22 She went to Paris, where, just before the outbreak of war, she made her first motion picture appearance (newsreels apart), when footage was shot with Fred Mace and Marguerite Marsh in and around the Cluny Museum.23

The Threads of Destiny (1914), a five-reeler directed by Joseph Smiley, was shot at the Lubin estate, Betzwood, and featured not only Evelyn but her young son, Russell Thaw, and her future husband, Jack Clifford.

In 1915, Thaw was pronounced sane by a New York court and he was released. He divorced Evelyn in Pittsburgh in 1916. The following year, she began her motion picture career in earnest. It must be admitted, however, that while she regarded her vaudeville career as something of enormous importance, her films did not mean much to her. She accords them a mere passing mention in her autobiography: “I made two pictures for Joseph Schenck then six for Fox at Fort Lee.”24

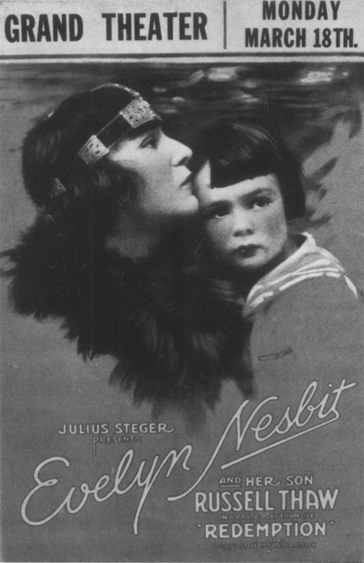

She starred in Redemption for Triumph in 1917, which Variety called “the best thing she has ever done upon the stage or screen.”25 Written by John Stanton, produced by Julius Steger, and directed by Steger and Joseph A. Golden, it showed a mother forced to confess to her grown son a mistake of her youth. (Evelyn was still only thirty-one!) “Redemption is continually suggesting it may be a revamp in part at least of her life’s history.” She played an actress who gained notoriety when young but who renounces the life at her marriage. Among the ghosts from her past is a wealthy architect! When she rejects him, he seeks a revenge which leads indirectly to the death of her husband and her own financial ruin.

Her son, Russell, again played in the picture. Wid admitted she screened well, but charged the picture with being a justification of Evelyn Nesbit’s errors. He advised exhibitors not to book it merely because of the star’s notoriety.26 The picture turned out to be a “terrific draw”27 and broke records. It guaranteed a film career for both Evelyn and her small son.

“Redemption is an illustration of the fact that those upon whom we look with averted eyes,” said Motion Picture Magazine, “may be more sinned against than sinning.”28

When the picture came to England, as Shadows on My Life, controversy broke out anew, and even though it was made clear that there was nothing sordid, gruesome, or repellent about it, the Cinematograph Exhibitors’ Association’s General Council passed the resolution: “THAT ANY FILM EXPLOITING THE NOTORIETY OF EVELYN THAW IS PREJUDICIAL TO THE BEST INTERESTS OF THE INDUSTRY.”29

The British Board of Film Censors had passed the film without comment (probably oblivious of Evelyn Nesbit’s identity). One exhibitor believed he was correct in saying that not one member of the General Council had seen the picture.

It was not the film, said a member of the General Council, but the exploitation of Evelyn Thaw’s notoriety to which the council objected. The thought of a young girl turning to her parent and asking “Who is Evelyn Thaw?” pained the chairman. They had been fighting to keep the screen pure, and it was absolutely wrong to show this film, owing to its publicity matter.

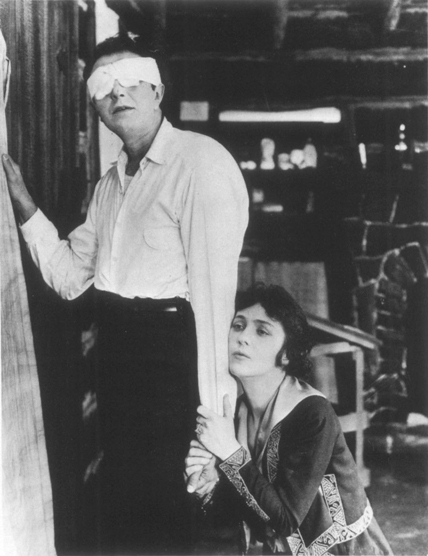

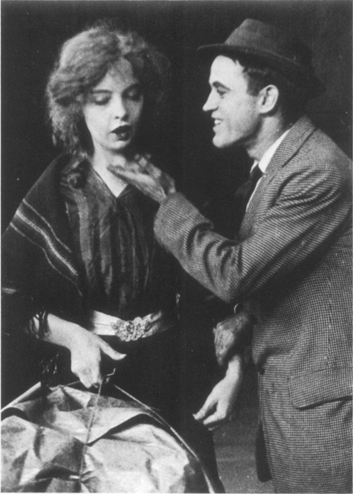

Evelyn Nesbit and Irving Cummings in The Woman Who Gave, 1918. directed by Kenean Buel. (National Film Archive)

After all the fuss, the (private) trade show was invaded by a large crowd of uninvited members of the public. The reviewers in the press were disappointed that all the objectionable features of the Thaw case had been sponged away. “It would not raise a blush on the cheek of your maiden aunt,” said the Glasgow Bulletin.

Nesbit’s contract with Fox led to a series of features, the first of which was The Woman Who Gave (1918), directed by Kenean Buel. The story included a scene of Evelyn posing, as she did in real life, for such celebrated artists as Charles Dana Gibson, and the brutal Thaw was symbolized by an even more brutal Bulgarian nobleman. Fox reported that bookings on the Nesbit pictures had broken all records.30 Her name was advertised thus: EVELYN NESBIT!

I Want to Forget (1918) was a German spy drama written and directed by James Kirkwood, which teamed Nesbit with Henry Clive, an artist of some distinction himself. Her acting was praised—“she becomes more of an actress as her screen experience broadens,” said Wid,31 but the story was not worth bothering about.

Kenean Buel’s Woman! Woman! (1919) was greeted by Julian Johnson in Photoplay32 as the sort of picture which made censorship inevitable. “If we are to have slime of this sort dragged through our projectors, we shall soon have our photoplays in the hands of a Russian secret police system—with no one but ourselves to blame. William Fox is handing the complacent Evelyn Nesbit scenarios the like of which Theda Bara in her boldest days never attempted.” He added that “the filthy story” would not bear synopsizing. Variety was more accommodating: a country girl, Alice, comes to the city and gets mixed up with the Greenwich Village “free love” crowd. She marries a young engineer (Clifford Bruce). His employer, a multimillionaire (William H. Tooker), offers gold and jewels for the chance to make her his mistress. When her husband falls ill in the tropics she takes up the offer, thus earning the money to save her husband’s life. But when her husband comes home and learns the truth he throws her out, together with her child, whom the millionaire claims as his. After the divorce, she returns to the country, but her reputation precedes her and she is ostracized. Her husband eventually apologizes; she tells him she made the greatest sacrifice a woman can make, and he failed to appreciate it. The millionaire proposes, but she turns him down and remarries her young engineer.33

My Little Sister (1919), also directed by Kenean Buel, was based on a novel by Elizabeth Robins, which caused something of a furor when it came out in 1913. It was the story of two country girls removed to London and trapped in a brothel patronized by the wealthy. “Sensational and brutally unpleasant,” said Wid, although he admired Nesbit’s acting: “She plays the part of the elder sister more effectively than it probably would have been played by many an actress possessing more technical accomplishments.”34

This was her last film for Fox, although not the last to be released. Her contract expired, and she returned to vaudeville, where she faced a lawsuit from the tax authorities and a divorce suit from Jack Clifford.

She made a picture called The Hidden Woman for Joseph Schenck which was directed by Allan Dwan. It was released in 1922, probably some time after it was made. Dwan found her a pleasant, ordinary woman: “She was a rough sort underneath, and tried to be dignified—but she was a nut.”35

In the film, Nesbit played a frivolous society girl who loses her fortune on the stock market and retires to the Adirondacks, where she incurs the wrath of local reformers.

“The murder didn’t make Evelyn Nesbit a big actress to me,” said Dwan, “just a dame that got into trouble. So I met her and saw she had limitations; she was squawking because she wanted to go to the country for the summer. She had a little place up in [Lake Chateaugay] New York, a cottage beside a lake, so I said fine, we’ll do it there so you can have a vacation and make some money. She thought that was fine. She was bedded down with a man who was a boxer. One day she says, ‘Won’t you do me a favor and come over tonight and referee a party I’m having?’ I said, ‘What do you mean?’ She said, ‘Come over and I’ll show you.’

“That night I went over with my assistant, I didn’t want to go in alone, and she was loaded up with these strange hangers-on, New York people, strange crowd, mostly pugilists, and they were having an ether party. I had never heard of an ether party; what they had to be careful of was that nobody had too much ether, or they would pass out and swallow their tongue. The referee’s job was to look them over and shake them up if they were too far gone. They started getting cock-eyed drunk on ether and my assistant and I were pretty busy until three in the morning waking up these people and tossing them out in the lake to sober them up. That pretty near turned me off.”36

Dwan telephoned Joe Schenck and told him the situation; Schenck came up and persuaded Evelyn to abandon her ether parties until the picture was finished. Dwan did not see her again until he met her in Atlantic City: “She was running a nightclub, but was doing well, making money, based entirely on the notoriety she’d got from the murder case.”37

Dwan did not know that her experiments with ether were an attempt to break away from cocaine and morphine, to which she had become addicted. She suffered from agonizing neuralgia and even tried suicide.38

Author Samson De Brier knew Evelyn Nesbit in Atlantic City and considered her a remarkable woman: “In those hypocritical years, when scandal both shocked and titillated the public, Evelyn wore her notoriety with forbidding dignity. And she was shrewd enough not to reveal the whole truth. Thus she negated her past and, perhaps, any guilt she may have felt.

“She had a dichotomous attitude towards her position in the affair. She resented being considered only as a ‘succès de scandale,’ but her questionable publicity did afford the opportunity to provide a living for herself and her son.

“She had great presence and an assured manner and she could never become an obscure housewife. Curiously, she never again made a ‘brilliant’ marriage or alliance. Yet her beauty was only more striking as she matured.

“She did not talk about the ‘case,’ as I was in my teens when I first knew her and did not have the skill to draw her out. I just enjoyed knowing her as a fascinating and beautiful woman. She often had me to dinner at her tiny and sparsely furnished apartment in Atlantic City. Her son was living with her there—a quiet boy.

“Years later, when I was in the position to offer her an interview on a New York radio station, she refused. She was sick and tired of going through the old story again. And years after that, when we had both moved to California, she was apprehensive about Joan Collins playing her part [in Girl on the Red Velvet Swing], because she did not know of her. She thought she would be portrayed by a famous movie star. Of course, none of them were young enough. After she met Joan Collins, she was pleased. And she was glad to get the money—her final chance to get a sizeable sum for her declining years. If only she had collaborated with a ‘ghost’ she could have made a fortune. But by that time she was plagued by ill-health. She moved to a little hotel way out on Figueroa Street, a location where no one here would ever think of going. I never saw her again. I was settling in to a very busy social life, and she lived so far away. I shall always regret not making more of an effort to see her.”39

BEULAH BINFORD Beulah Binford was a seventeen-year-old girl who became notorious after the arrest of Henry Clay Beattie, Jr., for the murder of his wife in Richmond, Virginia, in 1911. Although she was repudiated by Beattie on the witness stand, she testified that her association with him had begun when she was thirteen.

The president of the Levi Company, Isaac Levi, signed a contract with Binford and filmed her brief life at his Staten Island studio. The New York Evening World appealed to public sentiment to prevent the exploitation of this girl on film or stage. At the behest of Mayor William Gaynor, the commissioner of licenses informed Levi that under no circumstances would the film be approved. Levi said the film was intended to carry a moral lesson and a warning to other girls “to shun the temptation to which she had succumbed.”40

Leon Rubinstein, in charge of the picture and probably its director, too, had taken Beulah into his own house. He arranged a meeting for the girl and the members of the National Board and showed them the film. He was furious when they still refused to endorse it; he declared that Beulah was being robbed of her one chance to make an honest living. He would fight the ban. The Reverend Madison C. Peters declared that the picture was no more harmful than the play Way Down East: “The girl should have a helping hand extended to her. It is a blot upon the Christian ministry … that she had received no offers of aid or sympathy.” Surely, he said, she should not be held responsible for mistakes committed when she was thirteen. “Her story, instead of being one to damn her, is an indictment against a society that enables such things to be.”41

The film showed Beulah as a baby, left in the care of a grandmother while her mother played the horses. She grows up a tomboy and is seen taking automobile rides with a man, presumably Beattie. “Another picture shows her tear-stained and weary. It is labeled ‘Realization,’ ” said Moving Picture News. She tries to get work, but is harassed by men. The film ended with the murder and the third degree and scenes of the girl in prison. The picture was entitled The Wages of Sin.

The Board of Censors thought the film’s only appeal was to morbid curiosity: “The picture intrinsically fails to teach any lesson except one of sentimental toleration for the girl who takes easy opportunities to ‘go wrong.’ ”42

Rubinstein wrote to the trade press saying that his film sounded the warning of the dangers of parental neglect and pointed to phases of the social system that needed correction: “Have moving pictures ever before been devoted to such serious work?”43

Mayor Gaynor may have barred the film in New York, the Board of Censors may have condemned it for the rest of the country, but it was shown just the same. The publicity of the Beattie case aroused a tremendous demand, and the Special Feature Film Company announced in September 1911 that 116 towns—including New York—had shown it to 684,164 people.44

Two months later, Henry Beattie was executed and Binford, having achieved only a small role in a Richmond stage play, was living in seclusion in the Bronx.45

THE DE SAULLES CASE So common had it become to feature the central character of a famous or infamous event in a film that it was inevitable some producer would merely pretend to do so. When William Fox set up a film about the De Saulles murder, The Woman and the Law (1918), he gave the job of direction to Raoul Walsh. He had his eye on Miriam Cooper, Walsh’s wife, who resembled Bianca De Saulles.

“I’d go into a store or a restaurant,” said Miriam Cooper, “and hear people whispering behind my back, “There’s Bianca De Saulles!”46

Miriam Cooper fell ill; but Fox executive Winfield Sheehan wanted to produce the film while the story was hot, so the role went to a society girl. Sheehan soon called on Mrs. Walsh and told her the girl was lousy and, ill or not, she was needed for the lead. She gave in.

Exteriors were shot in Miami Beach, then just a long strip of sand, a few beach cottages, and a couple of big hotels. The co-respondent (based on dancer Joan Sawyer) was played by Follies girl Peggy Hopkins, later one of the most celebrated courtesans of the twenties as Peggy Hopkins Joyce.

The name De Saulles was changed to La Salle, but Fox had the brainstorm of omitting Miriam Cooper’s name from the credits, so an intriguing blank would appear opposite “Mrs. Jack La Salle.” Cooper said she would not tolerate that,47 but evidently she had no option. Variety recognized Miriam Cooper, at least in the second half. The film carried the title “Based on the sensational Jack De Saulles case,” which Variety thought made the whole thing utterly morbid and mercenary. “The story of the De Saulles case—a young wife is divorced from her husband, with her little boy allotted to each parent for certain portions of each year. The child goes to visit his father and the mother is taunted with the declaration he won’t be returning to her. She goes to the father and shoots him, the jury acquitting her.”48

Walsh’s direction was exceedingly classy, thought Variety, but the scenario was cheap and the situations obvious.

Fox might have employed a principal witness while he was at it and perhaps created a further sensation. His name was Rodolpho Guglielmi, an Italian immigrant who had played a few screen roles as Rodolpho di Valentino. (He had testified against his dancing partner, Joan Sawyer, in the divorce suit, but left New York when the murder took place—a journey which eventually took him to Hollywood.)49

THE CLARA HAMON CASE “No man or woman with the least trace of self respect would attend again a theater that slapped public decency in the face by defiling its screen with it.”50

James Quirk was referring to a film called Fate (1921), which aroused so much anger one might be forgiven for assuming it to be openly pornographic or an apologia for Bolshevism. In fact it was, like so many other films, a murder story. The only difference was that the alleged murderess played the leading role, and, to all intents and purposes, produced the picture.

It is important to realize that in real life Clara Hamon was acquitted. There was no doubt, however, that she did shoot her husband; she admitted it when she gave herself up. So whatever the provocation, and whatever the sentiment in her favor, she was a killer. It was this unpalatable fact that caused her so much difficulty when she came to make her picture.

The plot of the film, as related in the AFI catalogue, was the story of Clara’s relationship in Oklahoma with middle-aged Jacob Hamon (played by John Ince).51 Clara is an innocent high school girl when she meets Hamon, who offers to help pay for her education and employs her as his confidential secretary. Although Hamon is married, they become lovers. Hamon arranges a marriage of convenience between Clara and his nephew, F. L. Hamon, which enables them to travel together as Mr. and Mrs. Hamon. Jake Hamon strikes oil and rises to influence in politics and business, but his excessive drinking results in increased debauchery and brutality. On one occasion, he is particularly violent to Clara and she shoots him. He dies a few days later, and Clara flees first to Texas, then Mexico. She later surrenders, returns to Oklahoma, and is tried for murder, but is acquitted, to the joy of the courtroom audience.52

The promoter of the picture, W. C. Weathers, found the backing largely from men in the oil business who had been associated with Hamon. When Clara Hamon and he arrived in Hollywood, however, they had enormous difficulty persuading technicians to work on the film. The industry had apparently placed a ban on it. Such men as René Guissart, cameraman, and James P. Hogan, director, turned them down. And André Barlatier, who accepted $500 a week as cameraman, was drummed out of the American Society of Cinematographers as a result. The ASC was opposed to its members working on films in which people involved in public scandals were prominent. The group had specifically pledged that no member would be concerned in a picture exploiting the Hamon case. Barlatier took the job after this pledge had been made.53

The making of the film was clouded by rumor and counterrumor. Apparently, a member of the technical staff hired two thugs to beat up a young man who refused a job on the film and revealed all he knew about it around Hollywood. (He was uninjured only because he turned out to be a skillful amateur boxer).54

The film, which cost $200,000, was shot at the Warner Bros.’ small studio on Sunset Boulevard. When all the directors turned it down, declining a huge fee, John W. Gorman accepted $75,000 to make the picture. No one in Hollywood seemed to have heard of him. Born in Boston, he had been an actor on the stage, both legitimate and vaudeville, and claimed to be the author of six plays and 150 vaudeville acts. He started his film career with the Liberty Motion Picture Company and Pioneer, before setting up John Gorman Productions, for which he produced a handful of low-budget features.55

Gorman also wrote the scenario, being careful to subdue the sordid side and emphasize the moral. During the making of the film, a romance developed between the director and the leading lady, and in August 1921 Clara Hamon became Mrs. John Gorman.56

The picture had the desired effect. Once it was shown in Ardmore, Oklahoma, where the events occurred, sentiment toward Clara changed. A number of women subscribed for stock in the enterprise.57 Although production was complete, money was still needed to distribute the film.

When Fate opened in San Francisco, W. C. Weathers, the promoter, was arrested on a charge of violating the ordinance forbidding the display of censored films. It was the wrong town in which to open. The Arbuckle case had aroused deep feeling against the entire motion picture profession.58 District Attorney Matthew Brady announced that he was starting an inquiry into several prior affairs in which Hollywood people had taken part. An “unknown woman” was supplying the police with acres of information about such orgies.

Brady, encouraged by a local newspaper campaign, had banned Fate, which had been booked into the College Theatre on Market Street for an indefinite run. Branding the picture “thoroughly offensive,” a way for Clara Hamon (he referred to her as “Miss” Hamon) “to coin into money the blood of the man she murdered,” Brady promised legal action to prevent the showing of the picture following a private review by himself and police officials.59 This suggested that he had not actually seen it, “thoroughly offensive” or no.

Weathers asked for a jury trial, and the jury acquitted him in ten minutes on the grounds that no crime had been committed in the presentation of the film. It returned to the College Theatre, but business was poor, largely because the local press refused to advertise it—both editors and theatre managers felt the picture should not have been shown at all. (One suspects they didn’t see it either.)

James Quirk agreed with them: “Despite the clearly voiced opinion of the country that Clara Hamon … should not try to capitalize her disgusting notoriety on the screen, she proceeded to make a picture. The National Association of the Motion Picture Industry is fighting to exclude it from the theatres. No decent distributor would handle it [and] any exhibitor that showed it in his theater should be run out of town.”60

Other cities followed San Francisco’s example. Kansas City’s censors refused even to look at it. Undoubtedly a strong press campaign would have put the picture over, whether it was good or bad, but exhibitors dared not risk outraging the forces of reform so soon after the Arbuckle revelations. Clara Hamon’s sole plunge into the picture business was a disaster. But the press made play of that very fact: “Its reception has justified those people who maintain that pictures are daily growing better and cleaner—that the standard of production is far higher than it used to be. And that the public is still clinging to the right sort of ethics and ideas.”61

THE OBENCHAIN CASE When the murder first hit the Los Angeles headlines, it was more properly called the Kennedy Case. J. Belton Kennedy was a handsome, well-to-do young man, the sort of character who appeared in many a silent picture. His girlfriend was ideally cast, too. Madalynne Obenchain was a product of the new consumer society; obsessed with fashion, etiquette, and her own appearance, she was attractive enough to carry her narcissism with style.

To complete the melodrama, there was a villain, a character of uncertain origin called Arthur Burch. He was the first to be arrested, which was a trifle odd. But there was something odd about the whole affair.

It began when Madalynne fell for young Kennedy. She was still married to Ralph Obenchain. Evidently she felt more for Kennedy than he for her, for when she divorced Ralph, Kennedy tried to give her the slip. She pestered him with phone calls until his mother put a stop to it. Then she inveigled him into giving her a farewell drive in his roadster and begged him to call at the little cabin he owned in Beverly Glen, and there she … or someone … shot him.

Arthur Burch had a gun of the same caliber as the murder weapon, so the police picked him up. Madalynne was later charged as his accomplice. He stood trial alone, but the jury could not come to a verdict and he had to endure a second one. Meanwhile Madalynne went on trial herself, watched by members of the movie colony such as Leatrice Joy (who based part of her performance in Manslaughter on her). Madalynne spun a scenario so implausible no movie producer would have touched it: she had lost her memory from the moment she heard the shot until she had “woken up” much later. Ralph Obenchain had rushed to the court from Chicago to act as a character witness, convinced of Madalynne’s innocence and offering to marry her again if she were willing. He became the hero of the case, creating an extraordinarily favorable impression. Everyone sympathized as he covered his head with his hand, a picture of misery, listening to her love letters being read out in court.

The letters proved the great attraction of this melodrama. They were full of purple prose and betrayed the influence of movie subtitles: “Some day we will go down to the ocean together, and all this pain will have been forgotten, as we watch the great image of eternity and listen to the mournful music of the waves.”62

In the trials of both Burch and Madalynne, implausible stories were backed up by equally implausible yet curiously convincing witnesses. The story became more and more confusing, and then a second batch of letters, to another lover, were read out—in almost the identical phraseology. It must have been hell for Ralph.

But Ralph was not giving in to his misery. He was starring in a film, playing himself. A Man in a Million was a three-reeler, produced by an independent producer-director, Charles R. Seeling, who probably photographed it as well, as he was a former cameraman and specialized in making films as cheaply as possible.

According to Variety, A Man in a Million covered the early romance of the Obenchains at Northwestern University and showed Ralph’s youth, his entry into the army, “and numerous other events prior to Mrs. Obenchain’s arrest.”63 Variety warned that since Ralph has had no stage experience, “the film will have to make a stand before being booked.” Seeling arranged for Ralph to make personal appearances whenever the picture played a big city. Ralph, man in a million to the end, insisted that the profits would go toward the defense of his former wife.

That lady was meanwhile causing havoc at the county jail, where the other inmates resented the privileges she was receiving—a maid and a regular supply of candy and bottled water. Neither she nor Burch was ever convicted. Their defense, preposterous as it was, could not be satisfactorily challenged, and after a couple of trials each and a year in prison they were released.

“Considering that they were almost certainly guilty of a very cowardly murder,” wrote Veronica and Paul King in Problems of Modern American Crime, “they got off very lightly.” Mrs. Obenchain, perhaps encouraged by the fact that Ralph had made a film, began to study the art of acting. But she had chosen the wrong time to exploit her notoriety. Will Hays was now in charge, and she had less chance of breaking into the movies than of remarrying Ralph. It was just as well. As the Kings put it, “The United States public is rather tired of bad women who are worse actresses.”

In 1907, a photographer from the San Francisco company of Miles Brothers filmed the crowd outside the boxers’ training ring in Long Beach, California. When the film was shown in Chicago, three detectives recognized one of the men in the crowd and set out at once for Long Beach, where they arrested a wanted man called Rudolph Blumenthal.64

A great many films, however, served as vinegar in the wound of the collective pride of the police. As early as 1902, a Mutoscope loop called A Legal Holdup showed an encounter between a silk-hatted drunk and a policeman. The cop snatches his cigar, robs him of watch and wallet, pushes him onto a park bench with his nightstick, and strolls off. It was intended to shock, and it still does so. Yet the policeman as criminal was an insistent theme for muckraking journalists.

The association between moving pictures and crime has long fascinated audiences, bothered censors, and (usually) maddened the police. Being portrayed as a hero did not aid the policeman’s job when crime victims expected miracles. Being depicted as a buffoon was humiliating to him and a source of satisfaction to his opponents. (The police were particularly upset by the Keystone Cops.)65

Picture men learned to make films that would please the police because they were dependent on police cooperation. Filming in the streets, unless carried out by hidden cameras, often attracted vast crowds, impossible to control without the police. One wonders whether some of the early films were not a kind of gratuity on celluloid for favors past!

Stage people also found it essential to curry favor. Al Jolson’s first film was not The Jazz Singer, but a Vitagraph picture about traffic cops made in 1918 for the police benevolent fund and shown at a special benefit performance of Jolson’s Sinbad at the Winter Garden Theatre, New York.66

Irrefutable proof of police corruption came with the revelations of the Rosenthal case (see this page). Thanhouser released One of the Honor Squad (1912), a portrayal of a heroic policeman, and had to justify it somehow. So their advertisement read: “While the country is agog over the ‘crooked’ policeman and his connivance at gambling and murder, we spring this story of the Honest Copper.… Take your mind off Police Corruption and think, for a change, of Police Heroism. This picture points the way.”67

The Line-Up at Police Headquarters* (1914), coming out after the flood of vice pictures, had to be advertised as “Not a White Slave Picture … Not a Sex Problem …”68 It was a six-reeler, said to have been based on police records. Certainly, the police cooperated in the production. Former Deputy Commissioner George S. Dougherty appeared in it and undoubtedly wished he had not, for he was injured when a property bomb exploded during filming at the Ruby studios.69 The film depicted “the Official (Inside) Workings of the New York City Police Headquarters,” which, enthralling as it must have been, did not quite justify the description bestowed upon it in its advertising: “The Sort of Story that has Thrilled Mankind Since the Creation of the World.”70

In an era when female suffrage was a headline topic, people were intrigued by the idea of policewomen. To offset the illusion that they were used merely for a little light dusting, Balboa made The Policewoman, written by Frank M. Wiltermood, in 1914, and hired for the lead Mrs. Alice Stebbins Wells, said to be the world’s first regular policewoman.71

Policewoman Alice Clements resigned from the Chicago force to accompany a motion picture in which she appeared on a lecture tour. Chief Garrity appeared in it, too, so it had the blessing of the department. But not the entire department. The film, entitled Dregs of a Large City, was supposed to be an educational depiction of life in the old Levee, the red-light district of a decade earlier, but when it came before the Chicago censors, they banned it.72 The Levee summoned up sickening memories for older members of the force. In this Wild West–style frontier town, a morals squad officer had been accidentally killed by another detective, and the closing down of the brothels was accompanied by a battle royal between the two squads of police.73

What was unmentionable in drama was, oddly enough, acceptable in comedy. When the Girls Joined the Force, a Nestor comedy of 1914, directed by Al Christie, featured Miss Laura Oakley, the only woman police chief in the world, who was chief of Universal City.

In the film, a police chief is dismissed because of graft in his department, and the whole force is accused. Women take over, with Mrs. Van Allen (Laura Oakley) appointed to succeed the old chief. The entire police force of Universal City appeared in the film. Al Christie secured permission from the mayor of Los Angeles (not to mention the police!) to march the Universal City force through the city streets, headed by a band and followed by a line of political women. Moving Picture World wrote, “This incident, humorous for the dismay and disturbance it caused among the business sections of Los Angeles, is cleverly incorporated in the picture. Then we have scenes in the police station after the women come into power. What the women do not do to make the station a sublime dwelling place for the men isn’t worth doing.”74

The number of pictures about honest policemen who withstand the lures of politicians indicates how wide was the spread of graft. A typical example was a three-reel Selig picture of 1915, How Callahan Cleaned Up Little Hell, directed by Tom Santschi from an I. K. Friedman story. Santschi himself played John Callahan, an honest police captain, in a documentary-style drama entirely without love interest. “A cast with more tough looking men would be hard to assemble,” said Variety.75

Callahan refuses to release a pickpocket who is the crony of a ward heeler and is transferred to “Little Hell,” the worst district in the city. When the local political bosses set out to buy him, they find him incorruptible. But Callahan is in financial trouble—his daughter is ill and he cannot pay his mortgage—and the grafters make another offer. In real life, Callahan’s resistance would crumble at this point, or he would be beaten up or killed; in the movie, his detective colleagues come to the rescue. Callahan cleans up Little Hell, and he and the leading gangster become friends, the crook joining him in his fight against vice.76

Few dramas of the twenties dared to deal with police corruption, but the comedies gave the game away. Paths to Paradise (1925), a Raymond Griffith feature, opens with a police raid on a gambling joint. A detective passes among the patrons with a hat—soon brimful with dollar bills. The raid turns out to be a stunt by rival crooks, but the point is inescapable.

The police used censorship to control the depiction of crime on the screen—particularly their own. In 1913, Royal A. Baker, censor of amusements for Detroit’s police department, drew up a list of the activities producers should avoid showing:

•The wrongs committed by the agents of the law … must never be shown in films

•Pictures must contain a moral ending

•Don’t show suicide (ever)

•Never show strikers rioting, destroying property, or committing depredation or violence

•Avoid tricks educational to crime, including:

a) taking impressions of keys on wax, putty, etc.

b) cutting telephone or telegraph wires

c) turning railroad switches

d) criminals using autos as an instrument to assist depredation, escape

e) picking locks, blowing safes, using a “jimmy” or a “pinch” bar

f) badger game, white slavery, street soliciting, and “vulgar flirtation”

Detroit would not have permitted the outstanding Detective Burton series of two-reelers produced by Reliance the following year, which went into remarkable detail about the methods of both criminals and police. Detective Burton’s Triumph is reminiscent in style of The Musketeers of Pig Alley, but it displays the more advanced technique of 1914 with bold close-ups and smoother editing. It shows how “yeggmen” (safecrackers) operated, cooking dynamite in order to extract the nitroglycerine, then straining this “soup” through a scarf and pouring it into bottles. We see how explosive is affixed to a safe and how that safe is blown. We see how the criminals are identified from the Rogues’ Gallery and watch the police close in on them in a saloon, using a barely noticeable system of coded gestures.

Broken Nose Bailey (1914), another in the same series, shows police using the Bertillon system of identification, measuring every inch of a criminal (played by Eugene Pallette), particularly his broken nose. Introduced from France in 1887, this method used the photographic mug shot together with precise anthropometric measurements which together added up to an individual’s unique portrait—the dimensions of the head, the length of the right ear or left foot.

In 1911 Captain Joseph Francis Faurot, known as the “thumbprint expert,” appeared in a film called The Thumb Print about this new method of identification recently adopted by the New York criminal courts. A wife is about to be convicted of the murder of her husband, when Faurot shows the court the difference between the wife’s thumbprint and that of a man who had left his mark on a pair of shears—the murder weapon.77

Faurot, now an inspector and head of the NYPD Detective Bureau, worked with Vitagraph again in 1916 on The Human Cauldron, directed by Harry Lambart. The three-reeler had documentary sequences woven into a fictitious story about two gangsters and their girls caught by the police. One man is sent to Hart Island and a girl to Bedford Reformatory. Both these institutions were shown, as Commissioner Katherine Bement Davis led a tour of inspection. A number of other policemen also took part in the film, and Vitagraph player William Dunn was cast as a police applicant, among dozens of real ones.78

All of which may give the impression that the police were the friends of the moving picture. It was not so. They were often hard on companies working on location, insisting that they display their permits when filming. “Any time you made a scene in Los Angeles,” said Hal Roach, “you were compelled to have two policemen to see you didn’t break any law.”79 Confronted by cameras at scenes of serious accidents, the police would often stop the filming by arresting the photographers or smashing their equipment. The newsreel men covering the Passaic strike of 1926 were indiscriminately clubbed by police and had their cameras destroyed. (Next day, the newsreel men returned in armored cars!)

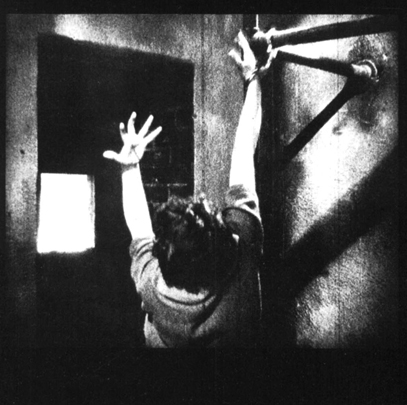

The police blamed the movies for the increase in juvenile crime and for giving the public an unflattering picture of their work. There had been much speculation about the “Third Degree” thanks to films like The Burglar’s Dilemma (1912), directed by D. W. Griffith for Biograph, from a scenario by George Hennessy. A murder is blamed on a young burglar (Bobby Harron). The police open their interrogation in brutal fashion, ramming the burglar’s face against that of the corpse. Then, in a naive and obvious manner, Griffith presents the hot-and-cold treatment of the third degree. An unpleasant cop threatens and intimidates the burglar, then a pleasant cop takes over and calms him down. Eventually, the corpse (Lionel Barrymore) recovers and the cops let the young burglar go—reluctantly.

In the antigambling picture The Wages of Sin (1913), a Mafioso is arrested; at the psychological moment, the blinds are raised and the corpse of a man he is accused of murdering is revealed outside the window. The Italian breaks down and confesses.80

The Third Degree, a Broadway stage success by Charles Klein, was made into a film in 1913 by Barry O’Neil, for the Lubin Company. No one had any illusions about the subject; the picture was described as “the secrets of the modern torture chamber” and “the real story of the police method of torturing a confession out of a victim.”81 There was even an unscrupulous police captain (Bartley McCullum), determined to wring a confession out of his victim at any price. The confession is finally obtained through hypnotism, which stirred up a great deal of controversy in the newspapers.82 The picture was as huge a success as the stage play.

The viciousness of the third degree could hardly be exaggerated. Searching for the ringleaders of a riot of 1913, detectives pointed a loaded revolver at the head of a young worker and threatened to shoot unless he confessed; when he still refused, they pistol-whipped him. A detective on another case was sentenced to a year in jail for cruelty.83

Police brutality was almost eradicated from the screen under Hays, but the occasional independent film obliquely referred to it. Edward Sloman’s The Last Hour (1923) showed a private detective leading a squad of policemen and committing a cold-blooded murder. Despite the presence of the law, he receives not so much as a reprimand. But by 1923, audiences would have regarded that as a flaw in the story, not the system.

From Moving Picture World, March 29, 1913.

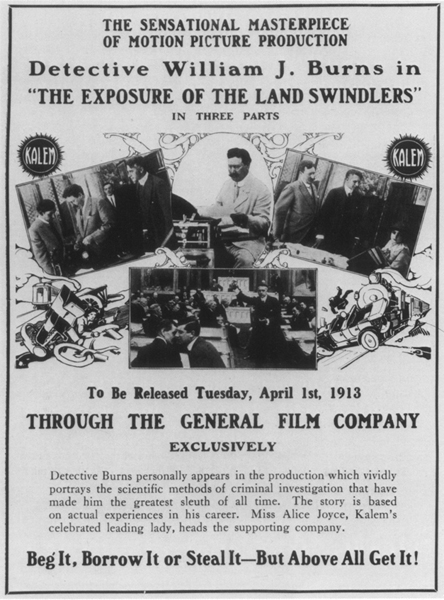

When it was common practice for films to be reprinted—or duped—and illegally exhibited, a company called Monopol hired the William J. Burns National Detective Agency to prevent infringement of a valuable Italian film. It was little more than a publicity stunt (by Frank Winch, former press agent to Buffalo Bill), but it was an impressive one. Perhaps it awakened a producer to the possibilities of using William J. Burns in a film, for a year later he appeared as a central figure in a Kalem three-reeler about political fraud, The Exposure of the Land Swindlers (1913), with Alice Joyce. The trade advertisements, true to the spirit of a company upholding the law, urged exhibitors “Beg It—Borrow It or Steal It But Above All Get It!”84 The enthusiasm was understandable, for Burns was regarded as “the greatest sleuth of all time.”†85

Moving Picture World said the film “shines in the unwonted gloss of novelty.” The introduction of William J. Burns as a detective who investigates a land fraud using a dictagraph and other modern techniques87 was carried out with “telling and sensational effect.”88

Burns returned to the screen in 1914 with The $5,000,000 Counterfeiting Plot, a six-reeler, released by the Dramascope Company, written by George G. Nathan and directed by Bertram Harrison. The picture was produced under Burns’s supervision with the help of Clifford Saum and William Cavanaugh, and he appeared in nearly every shot, together with former members of the Secret Service.89

It was based on one of Burns’s most celebrated cases, the Philadelphia-Lancaster counterfeiting mystery. Scenes were shot at the Treasury Department, Washington; Moyamensing Prison, Philadelphia; Lancaster, Pennsylvania; and New York City. Burns showed on the screen how bogus Monroe-head hundred-dollar silver certificates were made. These counterfeits were so remarkable that the Secretary of the Treasury had to recall the entire issue of that currency, amounting to over $27 million.90

Burns was hailed in the advertisements as “the greatest living detective,” and to give his reputation an even more Holmesian touch, he was brought together in the last scene with Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, who congratulated him on his many successes. He was also given credit for directing the film, which might not have pleased him had he read the scathing review in Variety, which reported his speech before the opening night in New York, when, apart from declaring that Leo Frank of Atlanta was innocent (see this page), he said the picture people had taken “picture license” in making the film.

“The picture people didn’t take a ‘picture license’ alone,” said Variety. “It was an all-night license covering everything.” Variety criticized details: a counterfeiter pulling a proof from a half-tone plate—“when you can pull a proof from copper with bare hands you are going some.” Burns in Washington leaving his cab without paying—“if Washington’s that easy, let’s move there”—and the building in Lancaster being blown up to destroy the evidence, even though that same evidence had been shown being burned in an earlier scene. “Badly padded and fails to convince,”91 was their conclusion. Said Moving Picture World: “Not one foot of noticeable padding.… The camera might have been on the job at the start and ‘got its story’ while the original players were not actors nor acting.”92 Burns came across as an accomplished actor. “He is as much of a professional as anyone in the picture. His facial expression gave one of its best touches of humor and made the only loud ripple of laughter at the first performance.”93

The Great Detective William J. Burns assists director Raoul Walsh with his version of the Paul Armstrong–Wilson Mizner play The Deep Purple, 1920. (National Film Archive)

But the picture was involved in some unseemly squabbles over distribution and wound up in court.94

Burns did not have a high opinion of the new medium as entertainment. He thought most plots were so implausible they did nothing but harm. Crimes were committed with such ease on the screen that a potential wrongdoer could take in the technique at a glance, try it out for himself, and, before he was aware of it, be embarked on a criminal career.95

This was not enough to keep Burns out of pictures. He cooperated on several silent detective dramas, including Raoul Walsh’s The Deep Purple (1920). In 1930, he was tempted back by the production of twenty-six shorts dramatizing the crimes he and his coworkers had solved. One was The McNamara Outrage, about the dynamiting of the Los Angeles Times building; another was The Philadelphia-Lancaster Counterfeiters. All were produced by Educational Pictures.

Burns revealed that for years his men had watched movies, not only for entertainment but to catch fugitives: “When Lon Chaney made The Hunchback of Notre Dame, I remember, one of my men spotted an extra in a mob scene who was wanted for forgery. A wire to the Hollywood police did the trick and he’s still serving time.”96

Even more famous than Burns was William J. Flynn, the former chief of the U.S. Secret Service. During the war he had enjoyed great acclaim for his serial of sabotage and espionage, The Eagle’s Eye.97 In 1920, he decided once again “to tell all” for the motion picture screen.

J. Gordon Cooper directed the Chief Flynn stories, with Herbert Rawlinson in the lead. The official records of the Secret Service provided the basic plots, but the scenarios were written by Wilson Mizner. A celebrated humorist, Mizner could have given each episode a rare degree of authenticity, for he knew the underworld and was a gambling crony of the gangster Arnold Rothstein, who virtually ran New York City.98 Instead, he smothered them in hokum.

Photoplay wrote, “The first three pictures in the series are The Silkless Banknote, Outlaws of the Deep and The Five Dollar Plate. There is enough material in each of them for a five-reel picture. For terseness of action and for human interest, they rank with the O. Henry series … The ‘crook stuff’ is lightened with plenty of comedy and many scenes of unpretentious pathos.”99

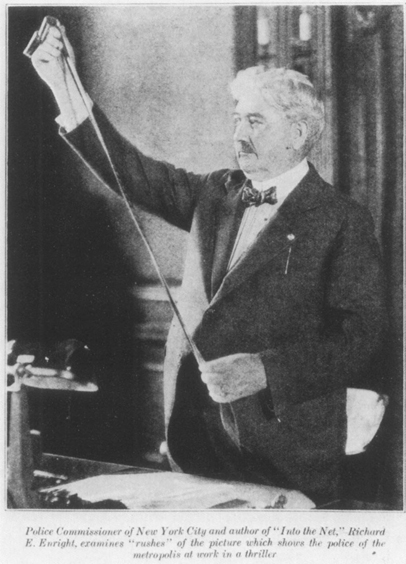

INTO THE NET Richard E. Enright, Police Commissioner of New York for eight eventful years, wrote a story about a heroic detective that was picked up by Malcolm Strauss, a producer. Frank Leon Smith was assigned to write the screenplay. “The story that became Into the Net (1924) was hard to write because of an embarrassment of riches,” said Smith. “When I asked Malcolm Strauss what good the Enright tie-up was to us, with some irritation he said: ‘Well, what do you want?’ In desperation I exclaimed: ‘The Brooklyn Bridge!’ To my amazement he asked, ‘When, and for how long?’

“It was as easy as that! The cops roped off the Brooklyn Bridge for us and George Seitz, the director, staged some good fights at mid-day in the middle of the bridge. Chase scenes up and down busy Manhattan streets became common and ritualized. First Enright’s official car and his personal aide ran interference; second, the car with the villains; third, the car with the heroic element; fourth, the camera car, with the director. Traffic cops had no advance notice. When they saw Enright’s car, they leapt aside, blew their whistles, and along we sped.

“We had good luck throughout the production—except once. Seitz was staging a street fight in Harlem between heroes and heavies when a plainclothes cop, not in on the act, ran up, and, reaching over the crowd, rapped one of our guys on the head with a blackjack.

“During the weeks Into the Net was in production, the newspapers seemed unaware that the Police Department was being used by a movie company. New York cops were even taken to Fort Lee to appear in interiors (they got $5 a day as extras, in addition, of course, to their city pay).

“As for Police Commissioner Enright, none of us ever saw him—until after the serial was finished.”100

When it was over, Smith was taken to police headquarters to meet the commissioner: “I was introduced as ‘the young man who wrote the scenario’ and I put out my hand. Enright took my hand, pulled me forward a little; big smile—and I thought he was going to say something. Nuts. Not a word for the guy who’d ghosted a 15 episode serial for him. He was pulling me ahead and out of the way so he could greet Miss Edna Murphy, who was in line behind me.”101

Into the Net, 1924, in production on Brooklyn Bridge. Jack Mulhall, right, is in danger of being hurled off. George B. Seitz directing, Edna Murphy center, and no sign of Police Commissioner Enright. (Note second camera lashed to girders, extreme right.)

But not only was the picture advertised as “Written by Police Commissioner Richard Enright of New York,” a poster contrived to suggest that he had directed it, too.102

Photoplay thought Into the Net sustained interest throughout and credited George Seitz for his exceptionally good direction. (The leading players included Jack Mulhall, Edna Murphy, and Constance Bennett.) The English were more critical: “However prominently the police may figure in their assistance to the hero, it says little for the Detective Force which could allow an exponent of the White Slave Traffic to carry on so elaborate an organisation in the centre of Long Island until it is brought to the notice of the police by means of a private detective.”103

As Frank Leon Smith pointed out, every serial involved the kidnapping of girls; these beautiful victims were the descendants of the “disappearing women” of the white slave films.

While I was writing this book, Into the Net was discovered in the vaults of the Cinémathèque Française—a total jumble, restored and retitled by Renée Lichtig.

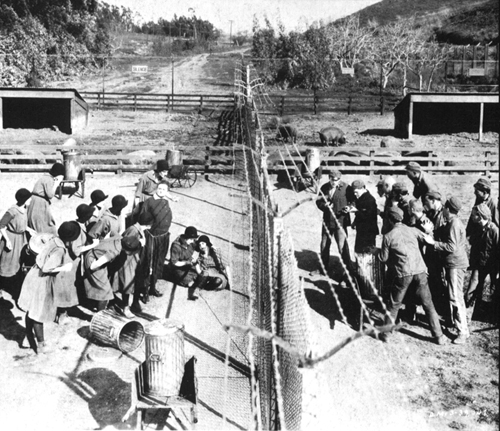

It was a version of the serial cut down to feature length in the twenties. As such, it has astonishing similarities to Traffic in Souls and was clearly an attempt to cash in on the same subject. This being the twenties, the white slave racket is run not by a reformer but by the obligatory Evil Oriental of so many serials. A police raid on a gambling den is directed in an identical fashion to the climactic police raid in Traffic in Souls; some shots might almost have been borrowed from Tucker’s film. Documentary authenticity is undermined by the use of interior sets—although there is location shooting at a night court. But the exteriors are exceptional in every way. Very well shot—they include high angles, rare at the time—they form a valuable record of old New York. One wild chase sequence contains shots racing down Broadway from above Times Square, past the Flatiron Building down to Washington Square. The final race to the rescue is beyond parody; not only are there powerful police cars and motorcycles, but columns of police horses, so Seitz can shoot it like The Birth of a Nation, and even motorboats so the Oriental, escaping aboard a steam yacht with a heroine, can be apprehended at sea. (He dives overboard, presumably to reappear in a future serial.)

Richard Enright was later responsible for organizing a special squad of policemen to cope with the crowds at movie premieres in New York City.104

Publicity for Into the Net, 1924. From Photoplay, November 1924.

The fear that films about criminals would create criminals began, appropriately enough, with The Great Train Robbery (1903)—the famous Edwin S. Porter “Western.” In 1912, the Philadelphia Record carried this headline:

BOY IS TO HANG FOR PICTURE PLAY ACT

Young Bishie’s Express Robbery Tragedy

an Exact Reproduction from “Movies”

Slew Trusting Friend

Waited for Whistle at Long Curve So the Shot

Would Not Be Heard105

The paper stated that at the time of the crime, December 1911, The Great Train Robbery was being shown in a Scranton theatre. Moving Picture World disputed this charge, pointing out that The Great Train Robbery could not have been seen in Scranton or anywhere else in December 1911 since “the age and physical condition of the film forbade its going through a moving picture machine.” The film survived to be copied, and dupes are still being shown more than eighty years later, so that ends that argument. The boy could not have learned from the film to wait for the whistle so the shot would not be heard, but otherwise the facts fitted, so why not blame the film? Citing the moving picture as the inspiration for one’s evil deeds had already become such a common practice that reformers looked upon the medium as wicked and deplorable, a perverter of youth and a breeder of crime. Those who studied children were, for the most part, convinced that moving pictures had a great deal to answer for. Asked what proportion of disciplinary cases were attributable to the movies, a Chicago superintendent of child study replied, “I should almost say they all were.”106

But in a survey of forty-two probation officers, conducted by the National Board of Review, five called motion pictures responsible for much juvenile delinquency, ten thought they contributed, and twenty-seven maintained they were not directly responsible to any appreciable extent.107 And in his 1926 book The Young Delinquent, Cyril Burt wrote that only mental defectives took the movies seriously enough to imitate their criminal exploits.

Yet the movies were the main source of excitement and moral education for city children.108 As early as 1909, Jane Addams wrote of the impact of the five-cent theatres on young minds: “Nothing is more touching than [to] encounter a group of children and young people who are emerging from a theater with the magic of the play still thick upon them. They look up and down the familiar street scarcely recognizing it and quite unable to determine the direction of home. From a tangle of ‘make believe’ they gravely scrutinize the real world which they are so reluctant to re-enter, reminding one of the absorbed gaze of a child who is groping his way back from fairy-land whither the story has completely transported him.”109

Youthful revellers stage a car fight—charging each other’s vehicles until one is wrecked—at a roadhouse. From Walking Back, 1928, directed by Rupert Julian, although this sequence may have been directed by Cecil B. DeMille.

While realizing that “the drama and the drama alone performs for them the office of art,” Adams added: “An eminent alienist of Chicago states that he has had a number of patients among neurotic children whose emotional natures have been so over-wrought by the crude appeal to which they have been so constantly subjected in the theaters, that they have become victims of hallucination and mental disorder.”110 She was also convinced that for every child driven distraught, a hundred permanently injure their eyes watching the moving films, and hundreds more seriously model their conduct upon the standards set before them.111

A survey of the effects of the cinema on children was carried out in Britain during the war. The Report of the Cinema Commission of Inquiry, instituted by the National Council of Public Morals, was published in 1917.112

One probation officer said he regularly took his charges to the pictures “with beneficial results.”113 If cinemas were closed down, there would be an immediate and immense increase in hooliganism, shoplifting, and street misdemeanors: “Fifteen years ago, street hooligan gangs were a real menace. Now such gangs are unknown in my district.”114

“Just imagine,” said a social worker, “what the cinema means to tens of thousands of poor kiddies herded together in one room—to families living in one house, six or eight families under the same roof. For a few hours at the picture house at the corner, they can find breathing space, warmth, music (the more the better) and the pictures, where they can have a real laugh, a cheer and sometimes a shout. Who can measure the effect on their spirits and body?”115

The commission was shocked by the revelation that the least desirable picture house was a better place for children than their homes or the streets and that no alternative entertainment was provided for them. “Except,” as one schoolmaster said, “the appalling entertainments provided by the Churches in the way of bands of hope and mission rooms. They are absolutely dreadful.”116

A magistrate was more complacent. “If the child is in the cinema seeing horrors, that child will not be in the streets stealing things off a barrow.”117

When the National Board of Review asked the chief probation officers of the principal American cities for their views on juvenile delinquency and the movies, the response was strikingly similar to the English report. Of forty-five who replied, only five indicted motion pictures as an important cause of delinquency—and two of those were in states with strict censorship, Ohio and Pennsylvania.

But religious groups responded as though it were still 1649. “Most of the pictures glorify crime,” said the Christian Advocate in 1925, “or depict the rotten trail of sensuality. It is sought to justify their exhibition by the explanation that they point a moral. As sensible would it be to drag a child through flames so that later he might feel the soothing effect of salve! Sear the mind of a child with rottenness, and no moral will ever produce relief, much less a cure.”118

The unconventional Mayor House of Topeka, Kansas, put it more succinctly: “If you have a boy who can be corrupted by the ordinary run of moving picture films you might as well kill him now and save trouble.”119

SAVED BY THE JUDGE Thanks to the liberal legal requirements of the time, Ben Lindsey was already an experienced lawyer when he was admitted to the Colorado bar in 1894, at the age of twenty-four. He became a judge in 1901 and discharged his responsibilities conventionally until a remarkable moment in his courtroom. He had just sentenced a young boy convicted of larceny when an appalling cry rang out. It came from the boy’s mother, crouched among the benches at the back.

“I was a judge, judging ‘cases’ according to the ‘Law’ till the cave-dweller’s mother-cry startled me into humanity. It was an awful cry, a terrible sight, and I was stunned,” recalled Lindsey.120 He adjourned the court and retreated to his chambers.

The boy was guilty, but should he go to prison when he had a mother and a home? The only course was for Lindsey to accept personal responsibility for the lad. He had no idea what he was going to do, except visit his charge, but probation proved so much more successful than prison that it transformed Lindsey’s outlook. “The old process is changed,” he wrote. “Instead of coming to destroy, we come to rescue. Instead of coming to punish, we come to uplift. Instead of coming to hate, we come to love.”121

“The criminal court for child-offenders,” wrote Lindsey, “is based on the doctrine of fear, degradation and punishment. It was, and is, absurd. The Juvenile Court was founded on the principle of love. We assume that the child has committed, not a crime, but a mistake, and that he deserves correction, not punishment. Of course, there is a firmness and justice, for without these there would be danger in leniency. But there is no justice without love.”122

Lindsey’s idea of trying youthful offenders in a special court spread across the nation. But he enraged those to whom property was more important than people.

Crime was the result not of character, but of environment, he asserted. What determined the environment? Ruthless private greed, flowering in an irresponsible capitalism. The true enemies of society were not the delinquents, but respected men in private life.123 “I sometimes felt like suggesting,” he said, “that we empty the jails altogether in celebration of the fact that the bandits who robbed almost everybody never got in them at all.”124

In retaliation, city officials and businessmen declared war on Lindsey. He was insulted and humiliated. Prostitutes were bribed to name him as a customer. The Democrats tried to drop him from their ticket, but he formed his own party and was elected unanimously.125 He caused 151 new laws to be passed,126 and delegations from many countries came to observe his methods. The Japanese even sent a photographer so the courtroom furniture could be accurately reproduced in Tokyo.127

Damned for his sympathy with the criminal, Lindsey received little official praise for his successes—the hundreds of delinquents who passed through his hands to become good citizens. He found an unexpected ally, however, in George Creel, a journalist appointed Denver’s police commissioner, who was to find fame during the war as chairman of the Committee on Public Information. Otis B. Thayer, a former Selig man, persuaded Creel to write a scenario about the Lindsey method for a three-reeler called Saved by the Juvenile Court (1913), or Fighting Crime. The story was in two parts. In one, fourteen-year-old Bob is arrested for picking coal in a railroad yard to save his poor family from freezing. In prison, Bob finds himself in the company of hardened criminals and becomes one himself. Released, he robs a bank and is killed in a gunfight with his pursuers.

In a contrasting story, Charles, a street waif, is arrested for attempted robbery. He is taken before Judge Lindsey, who gives him commitment papers and trusts him to make his own way to the Industrial School at Golden, Colorado, for training.128 Meanwhile, Alta, the boy’s sister, has been frequenting low dance halls. She is picked up by a policeman just as she is about to take her first drink, and Lindsey commits her to the girls’ school at Morrison, Colorado, where she receives an education. When the children return from school, they find that their widowed mother, under Lindsey’s influence, has opened a bakery shop and Charles has joined the motorcycle brigade of a large department store. One day, he stops the runaway horse of a banker’s daughter, and his heroism is rewarded with a job in the bank. He falls in love with the banker’s daughter, Beatrice. Alta assists her mother in the bakery and meets the man she wants to marry. Judge Lindsey is eventually called upon to officiate at a double wedding.129

Terry Ramsaye describes how this picture was pepped up with footage shot at the Cheyenne rodeo, and, after Creel’s drive against the red-light district, retitled people as with their parents; firm discipline was the only way to stop children from becoming criminals.

Judge Ben Lindsey (right) puts the case of the boy (Lewis Sargent) to Patrolman Jones (Russ Powell), in a scene from William Desmond Taylor’s Soul of Youth, 1920, written by Julia Crawford Ivers. (Museum of Modern Art)

Denver’s Underworld.130 The director, Otis Thayer, should have had a talk with the judge, for apparently he skipped the state owing a lot of money.131

The Columbine Film Company received many letters from child-betterment organizations pleased at having the work of Judge Lindsey introduced by means of the motion picture.132 Thus encouraged, Lindsey let it be known that he was considering directing features on the child labor question, following a series of articles he had written for the popular magazines.133 Sadly, nothing came of it.

In 1920, William Desmond Taylor followed the success of his Huckleberry Finn with The Soul of Youth, written by Julia Crawford Ivers. In this pre-Hays period, Taylor was at liberty to portray an orphanage in muckraking style, as a sordid dump, full of wretched boys who fought each other at the slightest opportunity. The most troublesome youngster (Lewis Sargent) escapes and lives rough on the streets until he is arrested during a burglary. He is brought before Judge Lindsey, who plays not merely a cameo but a proper role, with close-ups, titles, and reaction shots. (In one scene, he appears with his wife.) The judge comes across with warmth and sympathy, and the film itself is exceptional. The odd touch of sentimentality is offset by the realism of the orphanage scenes, the beautiful photography (by James Van Trees), and the atmospheric art direction of Wilfred Buckland.134