THE RUSSIAN REVOLUTIONS Although it hastened the end, Rasputin’s death was not enough by itself to bring about the fall of the Romanoffs. As no revolution materialized, the revolutionaries became increasingly demoralized. Lenin, exiled in Switzerland, thought the best thing he could do would be to emigrate to America. He doubted that his generation would live to witness the decisive battles of the revolution.210 Trotsky was about to leave for America himself; Stalin was in Siberian exile.

Thus, none of the future Bolshevik leaders were present when the Revolution at last broke out in Petrograd in February 1917,211 so swiftly and spontaneously that Russian filmmakers forgot to photograph anything on the vital first three days. They did not sort themselves out until March 1, when they filmed the aftereffects of revolution—the burned-out prisons, the ashes of official records, policemen in civilian disguise caught by the crowds. The material was compiled by the Military-Cinematographic Department of the Skobelev Committee into The Great Days of the Russian Revolution from February 28 to March 4 1917.212

Now that autocracy had gone, the people wanted peace—peace with victory. But army discipline had been shattered, and soldiers were deserting the front lines in droves. Alexander Kerensky, leader of the Menshevik government, staged a disastrous major offensive against the Germans in June. The people, desperately short of food, rioted in favor of Lenin’s Bolsheviks. The provisional government crushed an uprising in June, which it blamed on the Bolsheviks, and films were made to denigrate them—Lenin & Co.—and link them to the Germans—A Stab in the Back.

It was essential for the government to persuade America that despite the desertions and the disasters, Russia had no intention of withdrawing from the war. John (Ivan) Dored, a Russian who had lived in Los Angeles and worked as a cameraman, traveled to the United States to organize the editing and presentation of Russian battlefield footage. Russia to the Front was ready in a couple of months, and in September 1917 was presented at the Rialto, New York. Scenes of action against the Turks were followed by astonishing shots of the funeral procession of the victims of the Revolution, when virtually the entire population of Petrograd turned out to pay their last respects. One prominent family was not present; a subtitle explained that the tsar and tsarina were now “in an ordinary railway coach on their way to Siberia.”

How the immigrant audiences must have loved that! Reviewers praised the high photographic standard of the pictures, which had the quality “of conveying more clearly, more impressively than anything else possibly could the immense significance of the Russian Revolution in world civilization.” In the September 17, 1919, Moving Picture World one reviewer wrote: “One could scarcely view these scenes, in which surging masses of individuals of all classes joined hearts as one in celebrating what was not only the greatest event in the history of their country, but one of the greatest events in the history of the whole world, without being aroused to a high degree of enthusiasm and admiration for the heroes of the hour.”

But in Russia, enthusiasm for the war had evaporated, and the failures of the provisional government rallied the masses to Bolshevism, whose slogan—“peace, land and bread”—proved irresistible. On October 26, 1917 (old calendar), as the Red Guards besieged the Winter Palace, a congress at Smolny consigned Kerensky’s provisional government “to the rubbish heap of history.”b

When news of the February revolution reached America, a young Russian immigrant called Herman Axelbank, office boy at the Goldwyn Company in New York, remarked, “I wish I could take moving pictures over there; we don’t have any of our own of 1775.”

A few years later, Axelbank met a cameraman traveling to Eastern Europe. He commissioned him to film Lenin and Trotsky, pawning his possessions and borrowing from friends to pay the advance. The cameraman returned, in 1922, with film of the Kronstadt Mutiny and the Trial of the Socialist Revolutionaries. And so began the Axelbank Film Collection of Imperial and Soviet Russia.

Axelbank was never a Communist, nor was he particularly interested in politics. In 1921, however, he helped the Friends of Soviet Russia produce Russia Through the Shadows to raise funds for Soviet famine relief. The following year, he assembled With the Movie Camera Through the Bolshevik Revolution in three reels from material in his collection. In 1924, he made The Truth about Russia. And in 1928, he began work on his epic, Tsar to Lenin, for which he had the assistance of Max Eastman, who went to Turkey, to Prinkipo Island, to film Trotsky in exile, then edited the film and spoke some of the narration. The picture was not premiered until 1937, when American Communists who supported Stalin picketed the theatre to protest the portrayal of Trotsky.

Although the Soviet government bought footage from him, Axelbank attributed various fires and thefts to the work of Soviet agents. Nonetheless, the collection survived until Axelbank died in 1979, when it was split up, part going to the Hoover Institution and part to a German collector.

BETWEEN TWO FLAGS A Russian-born Jew named Jacob Rubin, an unusual combination of prominent banker and convinced Socialist, traveled to Russia in 1919 as a supporter of communism. He landed at Odessa and was thrown into jail by the Whites. Under sentence of death, he endured unspeakable privations until the American Red Cross obtained his release. He could easily have escaped in the evacuation of Odessa, but, realizing he was witness to history and anxious to join the Red cause, he remained. Though shot at and shelled, he survived to welcome the Reds, with whom he got on so well that for a time he controlled the government of Odessa. With his knowledge of American business practices, he transformed the inefficient Russian methods. He was able to prevent a Red Terror, to abolish capital punishment, and to give the Jews of Odessa religious freedom.

The frantic population evacuates Odessa before its occupation by Soviet troops in Between Two Flags, 1920.

Even though elsewhere the Soviets were executing thousands of people daily, they were sensitive about the worldwide publicity given to the Red Terror. Jacob Rubin, still an idealist, regarded these stories as wild exaggerations, like tales of German terror in the war. At a meeting to discuss the problem, a commissar put the question directly to the Americanitz.

“The thing to do,” Rubin replied, “is to fight the White guards with their own weapon. That is, show the world the White Terror—the atrocities committed by the Denikin regime during its occupation of the Ukraine. The way to do this is by producing a moving picture, showing the pogroms upon the Jews, the raids upon stores and market-places, the cruelty, the injustice, the extortion, the graft, the many executions.”213

The suggestion was applauded and adopted unanimously. A committee of five, with Rubin as chairman, was appointed to write the scenario. It became the story of his own experiences, his prison life, his death sentence, his release, and the series of White atrocities he had witnessed or learned about. The film was to be called Between Two Flags, and it was to be directed by Alexander Arkatov,214 who had made Jewish films before the Revolution. Rubin was to play himself.

The scenario was so enthusiastically received that 500,000 rubles were appropriated for its production. Rubin was appointed natchalnik (chief) of foreign propaganda, given a smart khaki uniform and a regiment of soldiers, and authorized to requisition transport and other supplies for the picture.

Completed in five weeks, the film was first shown to an audience of 500 in the former palace of a sugar king. “There was such a demonstration of enthusiasm as I never witnessed in the United States outside of a political convention.”215

The liberal regime in Odessa displeased Moscow, and Rubin was deposed and left the city. His fate might have been sealed had it not been for the film, which mitigated the anger of the commissars, who regarded it as “valuable propaganda.” It was fortunate that Rubin did not stay in Odessa, for when the Whites recaptured the city they staged a public bonfire of agitki (propaganda films), arrested a director, and shot one of the actors.215

Disillusioned, Rubin remained in Moscow for some time, but he longed to return to America. When he finally received his visa, a last-minute impulse caused him to try to smuggle out his film—a foolhardy action that caused him agonies of fear on the long train journey to Estonia. Had not a blizzard felled the telephone lines, he would have been escorted back to Moscow under arrest, for his theft had not passed unnoticed. He was so frightened that he handed the film to the secretary of the Estonian Legation, and his book makes no further mention of it. Presumably, though, as the secretary’s diplomatic baggage was exempt from search, the film came through safely. Although there is no sign of it, alas, either side of the old Iron Curtain.

A still from Between Two Flags, 1920. From Jacob Rubin’s book I Live to Tell.

The death of a Communist. Reenactment of a scene which occurred at the Odessa Prison, January 18, 1920. As he leaped to his destruction this Communist-patriot cried, “Welcome, Liberty!” (From the motion picture made under Communist auspices, directed by Mr. Rubin.)

Jacob H. Rubin, author of Between Two Flags.

The American picture business had taken little notice of the February revolution, and it studiously ignored the new one. Yet there was an audience passionately concerned with events in Russia. The Fall of the Romanoffs and Rasputin, The Black Monk had played to packed houses. An “unprecedented box-office rush” led to special midnight performances at New York’s Rialto of news films of the February revolution, and a “special” featuring the Man of the Hour, Kerensky in the Russian Revolution of 1917, was released with the slogan “Action Pathos Thrills.” Even though its subject was on the run, audiences crowded the theatre. Yet when the October Revolution occurred, no feature film was made about it.217

Author Gilbert Seldes had his own theory about this: “The October revolution, as opposed to the Kerensky one, was the first revolution in any country since 1776 which was not based on our revolutionary principles. Given slight differences, the French revolution, the 1848 movement, the upsetting of kingdoms on the Continent, even the February revolution meant democracy. They were following us. And bang, in October 1917 occurred a revolution which had the audacity, the goddam crust, to say that the American revolution was not the last one … as far as anyone was aware at all of what was happening, the awareness brought home to them this fantastic fact; that for the first time in nearly 150 years—we were not the New World. The Russians had started a new system; what right did they have? We invented revolution, and they turned it against us. The reflection of this in our movies was preposterous beyond words.”218

This reflection, like the sun blazing on glass, blinded people to the truth. The truth, or such fragments of it as we now believe, was frightening enough. The movies poured in generous portions of melodrama to make the incredible merely unacceptable.

LAND OF MYSTERY Considering the fear aroused by the very name of Bolshevism, it was an act of considerable courage—or bravado—to take a film company into the burning cauldron of Russia—or at least Lithuania. But this is what American director Harold Shaw did in 1920 for a British film called Land of Mystery.

To make such an expedition required the support of men in high places. One such man was associated with this project from the beginning, for he wrote the story. Publicity referred to him as “Basil Thompson [sic] of the Secret Service.” Such a claim can usually be discounted. An officer in the secret service would hardly remain secret by advertising his job in the newspapers. But Basil Thomson was an exception. He was not only a genuine secret service man, he actually commanded an entire section of British Intelligence.

The son of the Archbishop of York, Thomson was called to the bar after a distinguished career in the Colonial Service. He then became governor of a prison and, in 1913, assistant commissioner of the Metropolitan Police. In 1919, the Special Branch was expanded into a civil intelligence department and Thomson became its director.219

“The new Directorate was funded with Secret Service money,” wrote Nick Hiley, “and was permitted to operate both in the United Kingdom and abroad to counter the threat of Bolshevism.”220

Thomson, described by a colleague as having “the ‘Red’ bee buzzing long and loud in his bonnet,” appeared convinced that Britain was “seething with revolution and might well blow up any day.”221 The Daily Herald called his organization the “Blood and Shudders Branch.”222 He had been associated with an official film project during the war, and he evidently regarded Land of Mystery as a thoroughly worthwhile method of combating the Bolsheviks.

Another curious character behind the venture was Boris Saïd, an associate of the theatrical impresario Gilbert Miller. He was revealed in a court case to be an agent of Imperial Russia,223 but it seems likely that he was also working for—or with—Thomson’s Directorate of Intelligence.

The scenario for Land of Mystery was adapted from Thomson’s story by Bannister Merwin, a former Edison man. Director Harold Shaw224 also came from Edison, as did his future wife, the leading actress Edna Flugrath. Although she and her parents were born in America, Flugrath was as fluent in German as in English, which proved an advantage at the first location—Berlin, where from the window of her hotel she saw “machine guns being rushed through the street firing showers of shot indiscriminately into the people.”225

Only with the utmost difficulty were she and the company able to get out of Germany. They moved to the town of Kovnoc in Lithuania, newly independent of Russia and struggling to stay free of the Bolsheviks. Edna Flugrath was appalled by the filthy living conditions and the famine: “So desperately destitute were these poor people that their empty stomachs overrided their moral conceptions and they would shoot a person for bread. I used to lay awake at night and count the shots, and on one occasion I counted fourteen—fourteen victims to the uncontrolled hunger of the poor starving people.”226

Stanley Rodwell, the young British cameraman of Land of Mystery, 1920, with his American Bell and Howell camera. (Ken Rodwell)

So dramatic was this location trip that another player, John East, kept a record of it, describing it as one of the most eventful experiences in a crowded half century of acting. East’s grandson wrote it up at length in his book, ’Neath the Mask.227

Kovno, the scene of heavy fighting during the war, was in ruins. It was bitterly cold. The company had grown accustomed to the sight of corpses in Berlin; here, however, bodies by the roadside were the victims not of machine guns but of starvation. The vegetable fields were patrolled by armed guards day and night, and a constant stream of refugees filed through the town.

The filming began with a scene of the Bolshevik flag being torn down to be replaced by a Lithuanian one. “The actor assigned to this task narrowly missed death when troops opened fire on him.”228

On their return journey to Berlin, members of the company were relieved of “surplus eatables” under the pretext of requisition. The police did not discover the silver candlesticks and the icon which East had himself requisitioned from a ruined church and sewn into the lining of his overcoat.

The Kine Weekly felt that Harold Shaw and his company deserved congratulations for their enterprise in taking such a hazardous trip, but backgrounds did not make a photoplay. The magazine objected to the creation of a bad precedent—the use of a character well known in world affairs, under a slightly disguised name. “At least one writer in the lay press, deceived by a similarity of names, had stated that this is a true story of a living man, mentioning the man’s name.”229

Even the most outrageous of American propaganda films had not descended to lying about the private domestic life of a living individual, the weekly said, and it would be very bad for the reputation of this country were it to start here.

The film company made no bones about it. It announced at a press lunch that the film was about Lenin. The character was called Lenoff, and he was portrayed by Norman Tharp as the son of prosperous peasants—kulaks, no less. (Lenin was actually the son of a college teacher.) Lenoff loves a peasant girl, Masikova (Edna Flugrath). They become engaged, but Masikova encounters Prince Ivan (Fred Morgan), a member of the royal family, who sends her to the Imperial Ballet. She becomes his morganatic wife. This arouses in Lenoff a hatred of the regime and of society in general; he throws himself into the Bolshevik cause. Three years after the outbreak of war, he returns from exile to head the revolution. Upon the downfall of the tsar, Masikova and the prince escape. Lenoff tries a friend by telephone for aiding their escape and condemns him to death. He quarrels with his mother, and she is shot inadvertently as a substitute for this friend, who manages to buy himself off. When he hears what has happened, Lenoff goes mad. The final scene shows Masikova and the prince arriving in England.

The only surviving photograph taken at the Land of Mystery location, Kovno, Lithuania. (Ken Rodwell)

The film had many similarities to the 1916 The Cossack Whip. The realism of its backgrounds startled English audiences, accustomed to a cruder standard of art direction in their native films. The Bioscope praised the enthusiasm with which Shaw had treated his subject: “One of the most dramatic episodes is where a mad fanatic, jumping on to the High Altar, declares that ‘there is no God or I should die this minute,’ to be taken at his word by a young soldier who, shocked at the blasphemy, shoots him down on the spot.”230

The re-creation of the Imperial Theatre, showing the vast audience rising at the entrance of the tsar, was regarded as “a masterpiece of staging.”231 A similarly glittering event was held at London’s Winter Garden Theatre, Drury Lane, where impresarios George Grossmith and Edward Lurillard gave the film a magnificent premiere, graced by an array of dignitaries quite remarkable for a mere film. Thanks to Sir Basil, the Home Secretary came, together with the French ambassador, the Dutch consul general, and the cream of London society. They were not disappointed. Loud applause was reported for the real “Russian” scenes. Many called Land of Mystery a masterpiece to compare with Griffith’s finest in its portrayal of the dark despotism of tsarism and the “even greater tyranny under Lenin.”232

But there was a sour note. “It has been claimed that this film has an historic value,” said The Kine Weekly. “There is not an historic scene in it. The years 1914 to 1917 are simply dropped out. It has been said that it shows ‘the birth of Bolshevism.’ The question of Bolshevism is not touched; neither a capitalist nor an industrial worker appears, the characters being exclusively Romanoffs, ballet girls and peasants. But the fact that it is propaganda is indisputable, because the hero is a Romanoff and the villains are peasants.”233

A Jewish producer once explained the attraction of the picture business for members of his faith: because the commandment forbidding the making of graven images precluded them from practicing the sculptural or graphic arts, many found an outlet in music; but the theatre, and now films, provided an opportunity to manipulate an art that was not representational within the meaning of Mosaic law.234

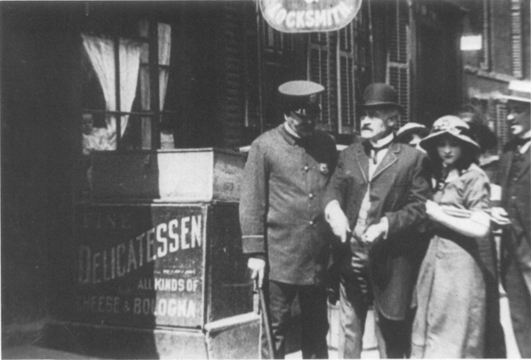

The motion picture also attracted Jews because it was a new business, with no tradition of prejudice. Like vaudeville, it was a branch of the legitimate theatre, the management of which was predominantly Jewish, David Belasco and Marcus Loew being the most notable examples. Exhibiting pictures required a relatively small investment, and the potential audience was vast. The Lower East Side, in 1908, had forty-two of New York City’s 123 movie theatres, for tenement dwellers were fervent picture fans.235

While the heads of the industry in the twenties were mostly Jewish, by no means all came from the ghetto. (Jesse L. Lasky was born in San Francisco.) And it should not be thought that Jews were exclusively interested in finance. They could be found in every stratum of the industry: writers (Alfred A. Cohn, Julien Josephson), cameramen (Hal Mohr, David Abel), directors (Ernst Lubitsch, Harry Millarde, John Stahl, Sidney and Chester Franklin—even the de Milles were partly Jewish), and players (Theda Bara, Ricardo Cortez, Carmel Myers, Alma Rubens). The Talmadge girls got the balance right for the early days of pictures—they were half Jewish and half Irish!

A surprising number of Jews on the financial side came from the garment industry; with its emphasis on fashion and public taste, it provided useful training.

It cannot be denied that in the beginning Jews encountered a certain amount of prejudice in Hollywood, where the residents, mostly Presbyterians, objected to the movie invasion and particularly to the Jews. And I found this description of a new executive in a letter of the time: “A little fat, sawed off, undersized, hook-nosed Jew simp by the name of Selznick (you don’t pronounce it, you sneeze it).”236

But outspoken anti-Semitism faded away in a business dominated by Jews, and despite the quips of Marshall Neilan, whose hatred of money men was notorious—“an empty taxicab drew up and Louis B. Mayer got out”—at least one Jewish filmmaker could assure me that he experienced no racial prejudice whatever in the industry.237

Dore Davidson as Isadore Solomon, Virginia Brown Faire as Essie Solomon, and William V. Mong as Clem Beemis in Welcome Stranger, 1924, directed by James Young for Belasco Productions. A Jew arrives in a New England town and the mayor and leading citizens try to get rid of him. A hotel handyman (William V. Mong) persuades the Jew to invest in an electric light plant for the town and when he brings this boon to the populace, they honor him. (National Film Archive)

The Jews were treated more liberally in America than in any European country,238 but the more immigrants arrived, the more anti-Semitic the United States became. Those who came from Germany in the mid-nineteenth century had been assimilated, and many had reached the middle class. When the influx of Jews from Eastern Europe arrived, those already established were dismayed. They themselves had experienced virtually no anti-Semitism, but they feared that the impoverished newcomers would threaten their hard-won status. They were charitable, but they kept themselves apart.

The ghetto dwellers were surrounded by hostility, for they often had the Irish on one side and the Italians on another. To reach other parts of the city, a Jew had to cross these Catholic enclaves, receiving a beating from time to time in the name of Christianity. These rivalries were immortalized in The Cohens and the Kellys films. “There are three races here,” said a title. “Irish, Jewish and innocent bystanders.”239 And even within the Jewish quarter, there was prejudice according to national origin.240

It was when the Jews began to leave the ghetto that anti-Semitism flourished. Clubs and resorts advertised “No Hebrews,” and as Jews moved into prosperous neighborhoods, Gentiles moved out. Denigration of the Jews became part of popular culture in newspapers, songs, vaudeville, and moving pictures. Much of it was the humor of stereotypes, applied indiscriminately to every race and nationality—but some of it was vicious.

Since the beginning of the cinema, Jews had been ridiculed, but the Rosenthal case made their criminal element front-page news, and the movies saw a proliferation of Jewish villains with names like Moe “The Fence” Greenstein or “Moneybags” Solomon.

“Whenever a producer wishes to depict a betrayer of public trust,” ran the report of the Anti-Defamation League, “a hard-boiled usurious money-lender, a crooked gambler, a grafter, a depraved fire bug, a white slaver or other villains of one kind or another, the actor was directed to represent himself as a Jew.”241

In 1908, Police Commissioner Theodore Bingham had claimed that half of New York City’s criminals were Jews,242 thus it would have been as reprehensible to sweep their sins under the carpet as to portray all Italians and Irish as pure in deed. And some of the films dealt with Jewish criminals without racial rancor.

A Female Fagin was made by Kalem in 1913. The most offensive thing about it was its title, without which few people would realize that the old woman is Jewish. Her name is Rosie Rosalsky, a clue only to the most knowing. Given every opportunity to carry on like a burlesque Jew, she is nonetheless restrained, a Fagin in deed only. She lives in a tenement and runs a school for thieves. Her pupils are two charming Jewish girls who work in a department store. It doesn’t take long to realize that in this East Side story almost everyone is Jewish.

At the dry goods counter, one of Rosie’s girls steals money from a customer’s purse and shoots it through the pneumatic tubes to her accomplice at the cashier’s booth. The customer raises a fuss, but nothing can be found. The owner’s daughter, Grace, decides to investigate. She leaves a pendant as bait; that night she spots one of the girls wearing it at the nickelodeon. She reports the incident, and the girl is called into the manager’s office. She might have got away with the theft, but Grace takes her position for a while, and, thanks to the pneumatic system, becomes the receiver of stolen property from the dry goods counter. The girls, confronted with their crime, break down and plead for mercy. A bargain is struck. They reveal the whereabouts of their teacher, and a group of men from the store, with a policeman, swoop down on Rosie, who is very roughly treated. The picture ends with the girls, looking happier, boarding with Grace and her new husband in their comfortable home. And her husband proves to be the department store manager.

Frame enlargement from A Female Fagin, 1913. The men from the store are led to the school for thieves. (National Film Archive)

Investigations after the Rosenthal case revealed such a network of Jewish crime that uptown Jews feared a pogrom if they did not act. Their organization, the Kehilla, created a Bureau of Public Morals to deal with the criminals themselves—and they were astonishingly successful.243

In 1914, a meeting of the Committee for the Protection of the Good Name of Immigrant People was called to discuss what it called “a notorious evil”—the imputation of the Jews, in certain films, of the crime of arson. Statistics proved the charge without foundation—“the Jews commit no more crimes of such a nature than any other nationality.” Several film companies, Edison, Kalem, Lubin, and Universal, sent emissaries, but their advice was only to get in touch with the National Board of Censorship.244

Nevertheless, direct references to Jewish criminals began to disappear from the screen, partly because more Jews were taking control of the picture business, partly because Jewish crime was itself fading out as the Italians took over the big cities.

But 1913 had seen perhaps the worst example of American anti-Semitism.

THE LEO FRANK CASE Leo Frank, a Jew from Brooklyn, was arrested for the murder of a girl at a pencil factory he managed in Atlanta, Georgia. His trial was transformed into an anti-Semitic propaganda campaign—former senator Tom Watson of Georgia, a Populist leader, wrote, “Our little girl—ours by the eternal God!—has been pursued to a hideous death and bloody grave by this filthy perverted Jew of New York.”245 Detective William J. Burns, hired by the Frank defense, only just escaped an angry mob for “selling out to the Jews.”246 The trial itself was a tragic farce—the true culprit was the principal prosecution witness—and Frank was sentenced to hang.

William Randolph Hearst expressed concern about the injustice of the Frank case; Senator Watson called him a tool of the Jews and cited the film Hearst had produced as an example. Hal Reid also produced a film, Leo M. Frank (Showing Life in Jail) and Governor Slaton. Frank’s mother and the governor’s wife appeared in it. When it was shown in New York, Reid delivered a glowing tribute to Frank and his mother. He was also impressed with Slaton, who had received more than a thousand messages warning him that if he commuted Frank’s death sentence his own would follow. “But with the confidence of his wife, who kissed him when he announced his determination, the Governor did the thing he thought should be done.”247 Reid showed this film together with his anticapital punishment story, Thou Shalt Not Kill (1915).

“Incidentally,” said Variety, “Mr. Reid talks more interestingly of the Frank case off stage than he does upon it, telling inside stuff such as he found out when in Georgia. Mr. Reid mentioned some unpublishable phases of the Frank murder matter that appear to bear out his assertion of Frank’s persecution.”248

Director George K. Rolands, of Russian-Jewish origin, made a five-reel reenactment called The Frank Case, which prophesied that Frank would be acquitted. The National Board of Censorship and the New York City license commissioner both banned the film because the case was being appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court, and any film on the subject would be in contempt of court. Although exhibitors protested that it was no more in contempt of court to review the case on film than in print, the picture was banned in Louisville, Kentucky—the first direct interference on the local level since the Jeffries-Johnson fight pictures were barred.249

Despite new evidence, the Georgia courts refused Frank a retrial, and he lost his appeal in the Supreme Court. Although two justices strongly dissented, the majority refused to intervene on the grounds that it was not a matter within federal jurisdiction.250

Having commuted Frank’s sentence, Governor Slaton ordered him secretly transferred from Atlanta to a prison farm. A furious mob was only prevented from hanging the governor and blowing up his home by the arrival of troops; in any case, Slaton had to leave Georgia and abandon his political career.

At the prison farm, a convict slashed Frank’s throat. While Frank was recovering, Tom Watson urged direct action: “Once there were men in Georgia, men who caught the fire from the heavens to burn a law which outraged Georgia’s sense of honor and justice.”251 To Watson’s triumph and delight, on the night of August 16, 1915, twenty-five men took Leo Frank from his sickbed and hanged him. “Lynch law is a good sign,” Watson had written. “It shows that a sense of justice yet lives among the people.”

Before the corpse was cut down, Pathé News managed to get shots of it which were included in its weekly newsreel. Atlanta police did not object to the film itself, but they strongly objected to the way manager Logan of the Georgian Theatre advertised it. He drove through the city in a large truck, with a set of chimes playing and a sign splashed along the sides: “Leo M. Frank lynched. Actual scenes of the lynching at the Georgian today.” The theatre had an exceptionally large Jewish patronage, and Logan alienated them all.252

Gaumont News, released through Mutual, also showed shots of the lynching ground, the crowds assembled there, and the judge who asked the onlookers to let the body be taken home in peace. Another scene showed Mrs. Lucille Frank, the widow, picking flowers, probably shot days earlier but nonetheless a useful bridge to the funeral.253

In Philadelphia, picture and vaudeville theatres were visited by the police and “requested” to refrain from showing any film depicting the Frank hanging or the trial. Managers cooperated to the extent of removing the item from the newsreels.254

“During the hysteria surrounding the lynching,” wrote Steve Oney, “the Ku Klux Klan … held its first cross burning atop Atlanta’s Stone Mountain, thus reinvigorating itself for a new life.”255 As for Tom Watson, his anti-Semitism brought him new glory in 1920, when he was reelected to the Senate seat he had held thirty years before. Once he had been a radical. Now, attracting disparate elements from both extremes, he became a bewildering combination of arch-patriot and opponent of Red-baiting, militarism, and the trusts. When he died, two years later, the Ku Klux Klan sent a cross of roses eight feet high.

The State of Georgia did not grant Leo Frank a posthumous pardon until 1986.

HENRY FORD The automobile manufacturer Henry Ford was also a radical in many ways; he too was opposed to militarism and the trusts. His contempt for Wall Street was well known. A populist, he was convinced that the world war had been fought for the benefit of big business, and since big business was controlled by “International Jewish Finance,” in his eyes the war was all the fault of the Jews.

Had this been his privately held opinion, it would have been no concern of history. But Ford took over a small weekly newspaper, the Dearborn Independent, and boosted its circulation by making his customers his subscribers. And he used his newspaper to propagate his ideas—it was the Independent that offered the notorious forgery The Protocols of the Elders of Zion to the world.

Ford’s anti-Semitism brought joy to the Corn Belt and did wonders for Klan recruitment. Referring to the Leo Frank case, Ford’s paper said it was “not without reason that the Ku Klux Klan had been revived in Georgia.”256

The Independent, which called itself “the chronicler of neglected truth,” had already attacked Hollywood by printing the “confessions” of a “producer” who declared he would rather see his daughter dead than on a studio lot.257 This was in keeping with the theme of The Protocols, which urged Jews to stoke the fires of immorality to prepare for the immolation of the Aryan world and the eventual seizure of power by the Jews. Ford called upon the American people to rise up and protest at the “Jewish control” of the people’s entertainment.258

Moving Picture World splashed its reply across two pages: “If the screen were Jew invented, Jew owned and Jew controlled, it would stand today as the greatest monument to Jewish achievement in all the history of that race because no other thing in modern or ancient life has developed with such amazing speed, with such astonishing progress toward perfection and with such tremendous service to all mankind.”

There were Jews, “and some mighty good ones,” in the picture business, and it was a cause for pride that no bigotry had barred them. But the business had attracted men of all races and religions. “Down to this very day and hour there never has been a control of any group of religionists or racialists and there is no movement evident toward such an end.”259

Of course, by 1921 the industry was largely controlled by Jews, but they could hardly be accused of forcing Jewish propaganda on American audiences. They did not misuse their power in the way Henry Ford was currently misusing his.

One casualty of this was the Ford Educational Weekly. Between 1914 and 1921, Ford released a film a week—factual one-reelers which were often of great educational value—offered free until 1919, when a nominal charge was levied. The fee, together with Ford’s anti-Semitic campaign in the Independent, finished the series, although there is no evidence whatsoever that the films themselves were anti-Jewish. Circulation dwindled from 7,000 to a mere 1,300 by August 1920, and in December 1921, the series was canceled.260 Exhibitors told Ford that if he wanted a release, he would have to build his own theatres.261

Henry Ford was not dissuaded from his campaign until 1927, by which time immense damage had been done: anti-Semitic articles from the Independent had been published in book form and translated into many languages. Among the industrialist’s many admirers was Adolf Hitler, who is said to have hung a large picture of Ford in his Munich headquarters and incorporated passages from the articles almost verbatim in Mein Kampf. And in one of those paradoxes of which history is full, Hitler’s future propaganda minister, Dr. Joseph Goebbels, would express the unbounded admiration for Hollywood which Henry Ford could not. Although he knew, if only from Ford, that Jewish talent and finance lay behind virtually every production, he held regular screenings in the 1930s and 1940s to show his men the standard for which they must aim. His diaries record how impressed he was with Gone With the Wind, the brainchild of Lewis Selznick’s brilliant son David. He ran Ben-Hur (1925, reissued 1931) several times: “Old Jewish hokum. But well made.”262 One of Dr. Goebbels’s most cherished beliefs was that the Jews had made no contribution to world culture. To prove this, he was willing to burn their books but not, it turned out, their films.

In 1937, whether he liked it or not, Henry Ford received a decoration from a grateful Hitler.263 By this time, he had apologized to the Jews, so the award was an embarrassment. But apology or not, the Jews did not forgive him. In at least one recorded case, Jews refused to allow pictures of Ford to appear in a newsreel.264

Against such a background, is it any wonder that the Hollywood producers avoided the subject of their own people? Many believed that any treatment might spread anti-Semitism. In any case, they craved acceptance as Americans. Of the films that were made, most dealt with poverty, and this brought the inevitable reaction from the Jewish establishment: “Why do you not show the successful ones, with their beautiful homes?”

And yet the subject could not be completely ignored because for some reason several of the biggest hits of the American stage and screen were stories about Jews. Abie’s Irish Rose ran for 2,532 performances on Broadway.265 Ben-Hur was a phenomenon on the stage years before it was filmed. And The Jazz Singer, with Russian-Jewish Al Jolson, introduced the era of talking pictures.

Of course, anti-Semites argued that most Hollywood films were Jewish propaganda anyway, with their emphasis on sentiment, mother-love, and the underdog. But that would suggest that the Irish, whose stories are full of such elements, are one of the Lost Tribes of Israel.

The Jew on the silent screen was not “invisible” as claimed by one historian,266 although to say he appeared in “a vast number of films,” as suggested by another,267 is somewhat overstating the case. But enough films with Jewish themes were made to throw fascinating light on the attitudes and concerns of the time. When the characters were portrayed with sympathy and admiration, the films helped to counter anti-Semitism. But the emphasis on assimilation, however gratifying to the federal authorities, dismayed Orthodox Jews, for whom assimilation was a tragedy. “Jews in hiding,” they called these new Americans.

As historical records, these films are priceless. They caught the streets of the ghettos when they were full of life, jammed with pushcarts and teeming with people. They recorded ritual and ceremony, and preserved the look of dress and costume. They re-created the pogrom and the process of immigration. They filmed the lives of ordinary people in what must seem to people today extraordinary circumstances. Had all these films been allowed to survive, what a history of the Jewish people would have been displayed!

SIDNEY GOLDIN If any man could be said to have depicted the sufferings of the Jewish people on celluloid, it was a Russian Jew called Sidney Goldin. Born in Odessa in 1880, he moved to America as a child and made his debut in the Yiddish theatre in Baltimore at fifteen. The picture business knew him as a rotund comedian and comedy director, although he made at least two highly profitable dramas, The Adventures of Lt. Petrosino (1912) and New York Society Life in the Underworld (1912). H. Lyman Broening, his cameraman on comedies at the Champion studios, retained a warm but bizarre memory of him: “He was nice, a great big oversize guy.… He’d sit down and start directing a scene and right in the middle he’d fall over and snore—sound asleep. He used to call me ‘Mr. Leeman,’ sounded better to him, I guess. He said, ‘Now, Mr. Leeman, when I go to sleep you come and wake me up—don’t hesitate. Come and shake me. I can’t afford to fall asleep in the middle of these scenes.’ So I got to be a bosom friend because I would always wake him up.”268

After a period with scenario writer Lincoln J. Carter in Chicago, and with Essanay, he joined Universal in 1913 to direct for the Victor Feature Film Company and Imp269 at Fort Lee. His first film for Imp was a three-reeler, The Sorrows of Israel (1913), which dramatized the plight of Russian Jews who could join society by converting to the Russian Orthodox faith, but only by sacrificing family ties. It involved pogroms and rescues by nihilists and ended with the statutory last scene of the couple sailing past the Statue of Liberty.270 It was ideal fare for the tenement districts and was popular enough to encourage Mark Dintenfass, supervisor of the Champion studios and head of Universal’s foreign department, to put more Russian-Jewish films into production. Goldin’s Nihilist Vengeance (1913), a two-reeler, was the story of the Jewish daughter of a banker and her love for a prince.

Irene Wallace, who had a small part in this film, played the lead in Goldin’s The Heart of a Jewess—Rebecca, a garment worker who pays for her Russian lover to come to America and go to medical school. Once he succeeds, he drops her for a wealthy girl,271 and on their way to the wedding the couple’s automobile knocks down poor Rebecca. The picture was praised for its atmosphere and for its scenario. “It is a pleasure,” said Moving Picture World, “to see Jewish people play Hebrew roles of comedy and sympathy, especially after so many sickening caricatures have affronted vaudeville audiences for years.”272

Actually, Irene Wallace was not of Jewish but of Northern Irish extraction.273 She played the lead in Bleeding Hearts or Jewish Freedom under King Casimir of Poland (1913), a highly colored three-reel melodrama in which wandering Jews, banished from other lands, arrive in Poland in the fourteenth century and plead for sanctuary from King Casimir, who allows them to stay. (The film did not show how Casimir created ghettos to isolate the Jews.) A reviewer complained of the “continuous violence” and declared that reproductions of history’s darker pages were gloomy and “should remain in the dust of the past.”274

A far more valuable film, if only it had survived, would have been How the Jews Care for Their Poor (1913), Goldin’s last for Imp. It was intended as a one-reeler, dealing with the work of the Jewish philanthropic societies but was expanded to two reels for the annual banquet of the Brooklyn Federation of Jewish Charities on December 21, 1913.275 Although it had scenes of great documentary importance, showing the work of hospitals, it was not a documentary but a simple story of Jewish immigrants from Russia. A mother dies, and her children are cared for by her brother. When he falls ill, they are taken into the Brooklyn Hebrew Orphan Asylum. The brother, recovered, is so impressed that he leaves the children at the asylum. When the small boy grows up and graduates, he delivers a lecture at the Brooklyn Federation, thanking them for all the help they had given his family over the years.276

Nineteen thirteen was a notable year for Goldin. He not only managed to make films for Victor, Imp, and Champion, under the Universal banner, but somehow managed to make a film for Leon J. Rubinstein of the Ruby Feature Film Company, even before his Universal contract had expired. This was called The Black Hundred or The Black 107.

The Black Hundred was a virulently anti-Semitic group in Russia, whose slogan was “Beat the Yids and the intelligents; Save Russia.”277 The tsar gave them his approval, and by 1909 they had succeeded in butchering 50,000 Jews.278

Goldin’s The Black Hundred was based on a famous contemporary Russian case in which a Jew named Mendel Beilis had been falsely accused of the ritual murder of a Christian boy. The film featured the celebrated Jewish actor Jacob Adler as Beilis and Jan Smoelski in a leading role. According to the publicity, Smoelski had been a revolutionary agent in St. Petersburg for two years, penetrating the councils of the Black Hundred, but he was discovered and had to seek the aid of the nihilists in order to flee the country.279

Sadly, The Black Hundred was not considered a good picture and was not taken seriously even by the commercial reviewers. But Variety’s critic conveyed the hunger of the ghetto audiences for such films:

“I caught the Ruby home-made Beilis in the thick of the movie-mad section of Rivington Street Sunday. Go to Rivington Street, just east of the Bowery, any Sunday after luncheon when there’s a racial film on the circuit if you want to know what a human gorge is. Surprisingly, the fee at the Waco theatre there for the Beilis show was only a nickel.… But at that, The Russian Black 107 [sic] isn’t worth more. It’s mushroom stuff. About the only sympathetic note its three reels contain is in the personality of the player selected to impersonate the much-advertised Beilis.

“A small body, a gaunt care-lined face, and an expression of unchanging and genuine apprehension, make one follow him through the theatric situations in which he is placed.… The manager of the Waco must have realized the playlet’s artificial texture, for the operator whipped the reels along at a sixty-mile clip, the persons zig-zagging on and off the screen like dance puppets. Although poor Mendel has a hard time of it on the screen, nary a bit of applause comes from the packed audience when the mimic jury acquits him.280 In some sections, the film may create a religious outbreak, for Mendel’s chief oppressor is shown to be a Russian priest who makes the sign of the cross while plotting the Beilis ruin.”281

When The Black Hundred reached England, the London County Council received a note from the Imperial Russian Consulate requesting that the show, at the Oxford Music Hall, be stopped. The council complied, for precisely one day, and then rescinded the ban. The Russian consul general was startled when he learned of this. “They will never dare to show that film,” he said. “They must not.… The pictures are a grave slander on the Russian police and the Russian people.”282

Sidney Goldin subsequently made a five-reel feature called Escape from Siberia (1914), which again emphasized the regime’s brutality. A Russian count is stripped of his military rank by his own father when he announces his engagement to a Jewish girl. The nihilists are the heroes, and the final sequence shows the lovers’ safe arrival in the Land of Liberty.283 Goldin also made an ambitious version of made leading man. The American Film Company at Santa Barbara gave him his first chance to direct. His films were characterized by a strong feeling for people; there was a refreshing realism about his work which marks it as exceptional, even today.

East and West, 1923, directed by Sidney Goldin, with Molly Picon, Sidney Goldin (third from left), and Jacob Kalich (right). (National Center for Jewish Film)

Karl Gutzkow’s 1847 play Uriel Acosta, which came out in July 1914, with the Yiddish actor Ben Adler and Rosetta Conn. Moving Picture World was disappointed that Goldin had tried to improve on the play and felt that the dramatic moments in the life of this great Jewish philosopher had been spoiled.284 And Variety commented, “In Jewish settlements, colonies, or neighborhoods, this picture will excite interest … otherwise it won’t create a ripple.”285

All of this must have been thoroughly discouraging to Goldin. He briefly turned back to comedy for a parody on Traffic in Souls called Traffickers on Soles (1914) in which the cops were Irish and Jewish, each squad led by an officer of the opposite persuasion. In 1915 he joined forces with the best-known Yiddish actor in America, Boris Thomashefsky, who had opened America’s first Yiddish theatre in New York, in 1902. Thomashefsky had become an impresario, and he felt there were enough Jews in the country to support photoplay versions of Yiddish stage successes. The Boris Thomashefsky Film Company produced The Jewish Crown, The Period of the Jew, and Hear Ye, Israel! Thomashefsky played the lead and Goldin directed all of them, but while the trade press reported that they had been made, there is no record of their release or of the Thomashefsky Film Company’s survival.

What happened to Goldin during the war is unclear. Afterward he went to Europe and ran the Eclair studios in Paris for a while. Then he moved to Vienna, where, in 1923, he directed Molly Picon and her husband, Jacob Kalich, in East and West (Mizrakh un Marev). According to Molly Picon, the film was popular with all audiences—in America it was called Mazel Tov—and in Vienna did better than Chaplin’s The Kid.286 Goldin also made Yizkor with Maurice Schwartz in 1924. He returned to America in 1925, reverting to acting for a living. In 1929 he wrote and directed his last silent, East Side Sadie, which contained sound sequences and introduced his daughter, Bertina Goldin, to the screen. She played a part similar to Irene Wallace in The Heart of a Jewess, a sweatshop girl who pays to put her boyfriend through college.287

Goldin then joined forces with independent producer Joseph Seiden to make Yiddish talkies. He ćame out of retirement to make The Cantor’s Son, based on actor and singer Moishe Oysher’s life story. Goldin had a heart attack halfway through production and died on September 19, 1937.288

HUMORESQUE The first Jewish classic was financed and produced by William Randolph Hearst, for his Cosmopolitan Productions, and it very nearly failed to appear.

It was directed by twenty-seven-year-old Frank Borzage, a non-Jewish Italian from Salt Lake City who had come to Los Angeles as a Shakespearean actor in a traveling stock company, fallen in love with the climate, and become an extra at Universal. He applied for a job as a character actor at Inceville and was promptly

Hearst wanted Borzage to direct a sophisticated story by Robert W. Chambers. Borzage recalls that he replied that he didn’t like that type of thing: “Have you got any human interest stories?” He was offered a book by Fannie Hurst: “There are a lot of short stories in it. You might combine three or four to make a feature film out of them. Take it home and read it.”

“So I took it home,” said Borzage. “The first story was Humoresque; it was a short one. I knew that was it. So I called Frances Marion, who was my writer. I said, ‘Frances, I’ve got the story.’ I wanted her to read out loud for me—I had a reason for this. So she read it out loud, and she couldn’t quite finish it. The chords in her throat welled up and I said, ‘That’s the test. That’s what I want. That’s our story, don’t you think?’ ‘Oh, yes,’ she said. So that’s how Humoresque was started.”289

The combination of Frances Marion and Frank Borzage was a powerful one, for Miss Marion shared Borzage’s ability to convey emotion. In an industry devoted to melodrama, it was a rare gift. Miss Marion was much in demand, having written for Maurice Tourneur, Albert Capellani, and Mary Pickford and the screenplays for The Yellow Passport (1916) and Darkest Russia (1917). She and Fannie Hurst were friends, and it was Hurst who took her to the Yiddish Theatre to watch Vera Gordon.290

A veteran of the Yiddish Theatre, Vera Gordon came from Russia. Humoresque was her first picture. “We were sixteen weeks making the picture,” she said, “but every minute was a delight and it did not seem like acting a part. You see, I know the East Side—the daily life of the people, their love of home and kindred. Like them, I have known the hand of oppression, the longing to rear my family in freedom. Because of this, I could give myself to the part.”291

Frank Borzage selected Gilbert Warrenton, who would later become the principal exponent of the moving camera and the “German” style in Hollywood, as cameraman. Hearst had no studio, and there was none available in New York, so the company took over an old beer hall, the Harlem River Casino, closed because of Prohibition, on One Hundred Twenty-sixth Street and Second Avenue.

Because sets for another picture occupied the main floor, Borzage and Warrenton had to work in the basement. Fortunately, their sets needed low ceilings anyway, but whenever the crew upstairs boosted the current, all their lights would blow.

For the scene where the mother goes to pray for her children, Joseph Urban built a stylized synagogue on the main floor. Warrenton suggested putting a shaft of light through a little window with the Star of David above the set. To make it more visible, he had two Irish electricians and a couple of prop men breathing smoke from cigars on to the set. Borzage was delighted with the result.

The opening sequence was shot on location on the Lower East Side. Said Warrenton: “To get rid of the crowds, which in that territory were awful, we secreted the camera in vans, and in one case used a pushcart. We also worked out of windows. In the ghetto, the buildings are close together. There are little platforms on the fire escapes … we also got up on these to shoot across at the opposite building, or down the street. Of course, we were not observed.

Mama Kantor (Vera Gordon) at the synagogue in Humoresque, 1920.

“We shot underneath the elevated, where the lighting was bad. Even when the sun is on the right slant, there is no room for the light to get between the ties that hold the rails. We did our exteriors as best we could under these conditions, and when I had to, I would plug in a booster light. We didn’t like to do this because it attracted attention. By doing it pretty fast, we got away with it a couple of times, and that’s how we got our exteriors.”292

Sadly, these glimpses of life on the Lower East Side are all too short.

Humoresque, released in 1920 and long considered lost, was rediscovered in 1986 by Bob Gitt, of UCLA Film Archives, and Ron Haver, during a search of the Warner Bros. Studios in Burbank. (Warners had acquired the original in order to remake it.) Although it has much to commend it, like all too many once influential films, its attributes are no longer remarkable. Its style of highly wrought sentimentality became identified with Hollywood for four decades and is common to a hundred other pictures. Though well directed and well photographed, it is basically hokum.

From Motion Picture Directing by Peter Milne (New York: Falk Publishing Co., 1922.)

The ghetto scenes, however, cannot be overlooked, although real exteriors are often intermingled with studio. In one sequence, a small girl takes a dead kitten from a garbage can, trying to warm it back to life; the boys who crowd around her end up by punching each other to pulp. This vivid ghetto atmosphere gives way to a more theatrical portrayal of life on Fifth Avenue. American films were never so picturesque dealing with the rich as with the poor! Nevertheless, the emotion of Humoresque is so near the surface that while you may note a certain disappointment in your reaction, you will also note the lump in your throat.

Fannie Hurst’s short story ended as Leon goes to war.293 The expanded story by Frances Marion begins before the war. Abraham Kantor (Dore Davidson) works in his brass shop, converting factory-made candlesticks from Brooklyn into aged antiques from Russia. His wife (Vera Gordon) cares for a large family which includes a mentally defective child, whose condition she blames on all she suffered in Russia.

The youngest son, Leon (Bobby Connelly), ruins his new suit, given him for his ninth birthday, by fighting for a girl, Minna Ginsberg (Miriam Battista). His father is angry; his mother forgiving. She sends Abraham out with Leon to buy him a birthday present. Leon sees a violin and becomes obsessed with it. Abraham says at four dollars it is too expensive and drags him away, protesting and tearful.

When Mama hears about this, she is profoundly moved. She had long prayed that one of her children should be a musician.

“Always a moosician,” grumbles Abraham. “Why not pray for a businessman?”

From the depths of the shop, Mama produces an ancient and dusty violin she has kept for just such a moment as this. And to her intense satisfaction, Leon proves he has talent. Soon, he gets the four-dollar violin and Mama goes to the synagogue to give thanks.

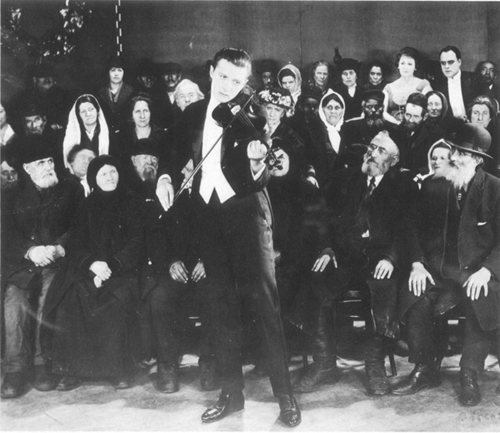

From the boy playing, we dissolve to Leon the young man (Gaston Glass) ending his first concert tour with a recital for the king and queen of Italy. It is ten years later. Leon re-encounters the girl from the ghetto, now Gina Berg (Alma Rubens), pursuing a singing career. They become engaged.

The Kantors are no sooner back in New York when America enters the war and Leon joins the army. Before he goes, he stages a concert for his own people—the people of the ghetto. (And the shots of the audience reveal that Borzage filled the concert hall with authentic Lower East Siders.) He plays the Kol Nidre, the prayer of atonement, and then his people call for him to play Humoresque, “that laugh on life with a tear behind it.” The concert is a wild success, and Elsass, the great manager, offers a contract at $2,000 a concert. But Leon says he has signed a contract with Uncle Sam. Mama Kantor is overwhelmed with sadness—surely, such a genius could be excused? But Leon refuses to hide behind his talent. “Look at Mannie,” he says, “born an imbecile because of autocracy!” Before he goes, he plays Humoresque to bring a smile to his mother’s lips.

The war ends. The troops return. A car arrives at the Kantors’ home, and an officer steps out. But it is not Leon—just a buddy to report that the boy is lying wounded in the hospital. A doctor explains to the anxious Gina that it was a shrapnel wound—a terrific effort would be his only hope, but not in his present state of mind, for Leon has given up, convinced he will never use his arm again.

Gina tends him in his convalescence, with constant assurances that she loves him. He answers, “Then you must leave me. My career is ended. I will not have you sacrifice yourself to a cripple.”

Humoresque, 1920. Leon Kantor (Gaston Glass) plays a concert for his own people—portrayed by Jews from the Lower East Side.

She walks away, heartbroken and falls in a faint. Leon rushes forward and lifts her up. He realizes that he can move his fingers, and, as Gina recovers, he reaches for his violin and tries to play the instrument. Mama Kantor hears Humoresque.

“God always hears a mother’s prayers,” she says. Replies Abraham, “I suppose a papa’s prayers have nothing to do with it?”

When the picture was finished, it was shown to William Randolph Hearst, who loathed it. Not that Hearst was anti-Semitic; in later years, despite being called a fascist, he interceded with Hitler on behalf of the Jews. It was simply that he could not understand why anybody would want to show the seamy side of life and call it entertainment. “The remarks from the releasing company [Paramount] bore out this theory that audiences would reject the picture.”294 The head of Paramount, Adolph Zukor, also detested Humoresque, saying to Frances Marion, “If you want to show Jews, show Rothschilds, banks and beautiful things. It hurts us Jews—we don’t all live in poor houses.”295

Hearst and Zukor decided not to release the film. It would require an elaborate advertising campaign, and they felt there was little point in throwing good money after bad. Frances Marion told me that it was only because the Criterion Theatre had run short of a film that they were obliged to put it on. It was booked in for a prerelease run of several weeks, to follow DeMille’s Why Change Your Wife?, that glamorous medley of sex and wealth. A press preview on May 4, 1920, suggested that Hearst and Zukor had been right. Variety said, “It proved to be something exhibitors should not bank on too heavily. Up to the middle it seemed like a wonderful picture, then it began to slip.… The continuity by Frances Marion was inadequate, and unless Miss Marion soon values her reputation more than her profits she will have to look alive to preserve what’s left of the former.”296

But when the picture opened at the Criterion, it was an immediate sensation. “Never before,” said Picture Play, “has such a perfect atmosphere of reality been communicated to the screen. Any fine work of art must have the power of drawing the spectator into its very center. This Humoresque accomplished. The life of the Jewish family is your life while you sit and watch the screen. You are as much a part of it as your teeth are part of you. I predict that it will live for years, and will be held up as a standard for aspiring artists to aim at.”297

A vital ingredient for the film’s success was its emphasis on mother-love. Curiously, the cinema had not paid a great deal of attention to mothers. There had been stories of maternal sacrifice, there had even been stories about abominable mothers. But a film which bombarded the emotions with scenes of maternal heartbreak—with a Jewish mother at that—could hardly have been more perfectly timed. The postwar generation was rebelling against its parents, and the story exploited their suppressed sense of guilt while it (briefly) restored their parents’ confidence.

Fannie Hurst (who was herself Jewish) was as surprised as Cosmopolitan by the success of the film. “The impact of Humoresque was quite extraordinary,” she said. “It’s been done several times since and it still brings in the most wonderful royalties! Yet the original wasn’t elaborate. It was a simply made picture. I had no part in the production. I had nothing to do with the filming of any of my books.

“A cousin of mine, who was a writer herself, accompanied me to the special showing at the Ritz-Carlton for an invited audience.

“ ‘Why, it’s a travesty of the story!’ she said. ‘The liberties they’ve taken!’ I made a sound signifying agreement, but actually I thought they’d done rather well. I enjoyed it.298

“The film was directed by Frank Borzage, a rough and ready man whom the cast found somewhat abrasive. But I liked him—he had a real feeling for his work, and the film put him on the map. That’s what pleases me most, I think, that my stories have put people on the map.”299

New York City set its stamp of approval on Humoresque by giving it one of the longest runs ever recorded for a feature picture. (It played for twelve weeks and broke box office records.) Photoplay awarded the film its first Gold Medal—the 1920 equivalent of an Academy Award. Wrote Frances Marion: “Nobody was more surprised—and hurt a little—than Mr. Hearst, who had just released another Marion Davies million-dollar opus which was playing to half-empty theatres.”300

The stunning success of Humoresque proved that audiences did not want their realism unadulterated, when a little hokum could make even squalor and mental disease acceptable, evoking a tear rather than a grimace. It set the standard for future Hollywood films about the plight of the Jews. Virtually all the silent productions were affected by an overdose of sentimentality, in the hope of repeating Borzage’s success.

HUNGRY HEARTS The long-lost Hungry Hearts was recently discovered in England and deposited with the National Film Archive. A remarkably complete account of the production can be put together from the interoffice memos and telegrams preserved by the legal department of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. It is thus possible for once to follow a social film from conception to release—and to observe the gulf between what was intended and what was achieved.

Hungry Hearts is a quiet film, with relatively little which could be described as melodramatic or sentimental. It was made so simply it might have passed as a poverty row production were it not for the obvious commitment of those on both sides of the camera.

When it was first proposed by story editor Ralph Block, Sam Goldwyn was enthusiastic, but he wanted an Americanization picture rather than a Jewish propaganda film.301 This may have been due to the fact that his associates in New York had just turned down Sophie Irene Loeb’s book Jewish Epic on the grounds that they did not favor Jewish plays.302

Goldwyn himself was an immigrant from Russian Poland, and when he approved the synopsis, he wrote, “Important you emphasize value old people in Russia attach to candles and other sacred things they part with to raise money for transportation to America. This is sure fire.”303

The story was based on a group of short stories by Anzia Yezierska, collected under the title Hungry Hearts. Yezierska was also born in Russian Poland, about 1881. When she was nine, her family came to America and lived on the Lower East Side. Her sisters went straight into the sweatshops; Yezierska went to public school and learned English. She started work at about age fourteen or sixteen. At seventeen, determined “to be a person,” she left home and began writing. In December 1915, Forum magazine printed her first published story, “The Free Vacation House.” She won an award for the Best Short Story of 1919 with “The Fat of the Land.” She handed the child she bore (during her second brief marriage) to its father and returned to her independent life.304

An enthusiastic item by a Hearst columnist aroused the interest of Hollywood in Hungry Hearts, her first book: “Here was an East Side Jewess who had struggled and suffered the desperate battle for life amid the swarms of New York. She had lived on next to nothing at times. She had hungered and shivered and endured. Why? Because she wanted to write. And that, ladies and gentlemen, is all there is to genius. An undying flame, an unconquerable hope, an unviolable belief that you are God’s stenographer.”305 Actually, she had graduated from Columbia University and worked for a time as a schoolteacher.

Sara (Helen Ferguson) with her admirer, the rent collector—nephew of the landlord (Bryant Washburn) from Hungry Hearts, 1922.

Yezierska’s agent, R. L. Griffen, sold her book to Goldwyn for $10,000, and the company invited her to work on the scenario at a salary of $200 a week. And so, in January 1921, this red-haired girl with a lifelong hatred of the rich set out for Hollywood—a famous writer.

The Goldwyn people were surprised by her disdain for luxuries. She refused any special treatment and would accept only a lower berth on the train.306 They booked her into an expensive hotel. “I could not stay,” she said. “I would have lost myself … I did not feel comfortable being waited upon. It smothered me. I told them I must go away and stay in some simpler place.”307 She also abandoned her chauffeur-driven limousine and took the trolley to work—though once was enough and she returned to the limousine.

Few of the studios regarded writers with the same respect as directors, but in 1919 Goldwyn had formed Eminent Authors, Inc., and had invited some of the most distinguished writers to Hollywood. When Yezierska arrived at the studio she was given an office alongside such celebrities as Rupert Hughes, Alice Duer Miller, and Elinor Glyn. She was astonished at being given stacks of fresh paper; her writing had been done on the backs of envelopes and scraps of wrapping paper. She had been assigned an eager secretary but had no idea how to employ her. Her method of composition was not a nine-to-five affair. The aura of luxury made her impotent as a writer.

Yezierska was interviewed by reporters and her story translated into such headlines as “Sweatshop Cinderella,” “Immigrant Wins Fortune in Movies,” “From Hester Street to Hollywood.”

She received a gift of roses from Paul Bern. “Thank you for giving us a book that’ll blaze a new trail in pictures,” he said. “You’re what I call a natural-born sob sister.”

“Do you mean that as a compliment?”

“I mean you’ve dipped your pen in your heart. You’ve got the stuff that will click with the crowd—the stuff that’ll coin money.”308

She detested Bern on sight; his dark Hester Street face seemed betrayed by his slick, movie star appearance. But it is hard to know how much of Yezierska’s recollection to trust. In her memoirs she had Bern assure her the picture would have a million-dollar budget, which was ludicrous, and around three zeroes more than it did cost.309 And there are many other discrepancies.

Bern, one of a large family, had come to the United States from Germany when he was nine and his parents were over sixty. The family lived in the New York ghetto with packing cases as furniture for a time, but, like Chaplin, whom he resembled in many ways, Paul used his wits to struggle free of poverty. Bern was said to be a nephew of Sigmund Freud,310 and certainly his analysis of pictures was unusually perceptive. An intellectual, he was described by his friend Sam Marx as “soft-spoken, with a slight Teutonic accent and gentle Continental manners.”311 Known as the best-read and most generous man in Hollywood, he had little in common with the character sketched by Anzia Yezierska.

In Yezierska’s account, Paul Bern is quite clearly a director. Certainly he had codirected a couple of pictures, and his experience included acting, writing, and even managing a film laboratory. But at this stage of his career he was both head cutter at Goldwyn and a producer. True, he had his heart set on directing Hungry Hearts, but Goldwyn’s heart was harder. This was to be a superspecial and he wanted “Hamburg” to direct it. “Therefore cannot consider Bern’s feelings in the matter,” said his telegram, bluntly.312

I had never heard of a director called Hamburg. As I read these telegrams to and from the home office in New York, I came upon other unfamiliar names—a Frenchman called Bordeaux, a man called Glasgow—and I realized that to avoid other studios indulging in industrial espionage, directors’ names were in code. “Hamburg” referred to E. Mason Hopper.

Born in Vermont and educated in Maryland, Hopper began acting at the age of fourteen. And that was the least surprising fact of his career. He was also a baseball player with a minor-league team, a cartoonist—he used this talent on the vaudeville stage—a student of chemistry, and he even invented a windproof matchbox.313 He became an interior decorator and a student of architecture and wrote sketches for vaudeville. He joined Essanay in 1911 as a writer and became a director, known as “Lightning” Hopper for his skill at cartooning, and directed Gloria Swanson and Wallace Beery, whose comic talents he helped develop. According to his own count, he made around 350 silent pictures and wrote 400 produced scenarios. And yet he remains unknown.

“E. Mason Hopper could have been one of the finest directors,” said his former assistant William Wellman, “but he was completely crazy. He’d rather cook than make pictures; he was a much better chef than he was a director. He was a little screwy, but he had great talent.”314

Ethel Kaye, the first choice to play Sara in Hungry Hearts—later dropped in favor of Helen Ferguson. (National Film Archive)

Yezierska had taken more kindly to the scriptwriter, Julien Josephson, a sandy-haired young man of endearingly scruffy appearance who had written some of Charles Ray’s tales of small-town life. She and Josephson worked on a story outline during her four-week stay in California. “We spent days and days in the search for one slim thread of truth,” she said. “Not one false note must be struck. And we did not force it. Not one line. When the sterile days came, we just sat back and waited and then after a while the life of the thing itself carried us forward so that it wrote itself as a story should.”315

She was equally impressed with the sets, designed by Cedric Gibbons. “We walked out of the office building to the studio lots and saw an East Side tenement, the rusty fire escapes cluttered with bedding and washlines, a row of pushcarts that seemed to come directly from the Hester Street fish market, a whole city humming.”

The sight of men working on the thatched roofs of the village houses transported her to her childhood. “The past which I had struggled to suggest in my groping words was recreated here in straw and plaster.… I closed my eyes and could almost see Mother spreading the red-checked Sabbath tablecloth. The steaming platter of gefüllte fish, the smell of fresh-baked hallah, Sabbath white bread. Mother blessing the lighted candles, ushering in the Sabbath. ‘This interior is perfect,’ I said to Josephson.”316

Once her four weeks were up, Yezierska returned to New York to fulfill her commitment to a series of lectures. She left behind a massive story outline—“enough for a twenty-reel picture,” groaned the front office317—and a reputation for being “difficult.”318 With her socialist sympathies, she did not hesitate to take financial advantage of the studio. To keep her happy, the studio promised to submit Josephson’s slimmed-down “technical continuity” for whatever comments she might care to make.

A few months later, the studio began casting the picture. Sam Goldwyn, in New York, tested a Russian-Jewish girl called Ethel Kaye319 and decided that she should play Sara,320 although a few days later he had second thoughts and suggested that Alma Rubens, another Jewish actress, might be more suitable.321

“Organization unanimously and definitely opposed to Rubens for Hungry Hearts,” replied Abe Lehr, who ran the studio. Leatrice Joy was also turned down. So was Carmel Myers, the daughter of a rabbi, who had just appeared in Cheated Love: “Good actress, but too American.”322 So Ethel Kaye got the part.

The role of the mother was even more crucial. Augusta Burmeister, who had played in George Loane Tucker’s wartime comedy-drama Joan of Plattsburg (1918), impressed Goldwyn, but when he brought Yezierska in for her opinion, she thought Burmeister looked more Irish than Jewish.323 Jacob Adler’s wife was interviewed. An actress called Cottrelly was considered. Yezierska said she was not the type. Goldwyn suggested having Mary Alden, a celebrated Hollywood character actress who had been in The Birth of a Nation, study Jewish mannerisms.324 Lehr replied: “Unanimously thought here Mary Alden could not possibly acquire Jewish mannerisms in short time between now and starting of the picture.”325 Lehr made an appointment to see Madame Thomashefsky, but she failed to turn up. None of this came to anything.326 With the start of production looming. Goldwyn took Yezierska’s advice and settled upon the Russian stage actress Sonia Marcel, who left at once for California.327 Lehr informed Goldwyn that Bryant Washburn had been selected for the juvenile lead, a surprising choice, for he was a very American actor, popular in light comedy. But Lehr justified the decision by calling Washburn “the only juvenile leading man we know of who acceptably photographs Jewish.”328 Perhaps equally important, he had been six years at Essanay and was a friend of Hopper’s.

Goldwyn asked Lehr if he wanted Yezierska to come out again. Lehr answered: “Don’t want Yezierska as aside from her being a hindrance to Hamburg she will make impossible a sane shooting schedule.”329 Last time, he explained, they either had to get her out of California or face devoting years to the development of her continuity.330 “I suppose she is just as much of a nuisance in the home office as she was here.”331

From New York, Yezierska had complained bitterly that the scenario was being reedited without her approval. Cleverly, she argued that unless she were consulted at every stage, Goldwyn’s policy, which had given authors complete faith in him, could not be carried out, endangering both artistic integrity and money-making potential.332 Lehr assured her that nobody was contemplating murdering her brainchild.

And it was true. The creative people associated with the film were devoted to it. They were convinced they had a great picture, and they worked on it with enormous enthusiasm.

Shooting began in late September 1921, and Lehr happily cabled Goldwyn: “Have never screened in any single day a finer or more satisfactory collection of rushes than what we saw today. Opening episode is full of beauty and convincing realism.”333

But the euphoria was short-lived. In the eight months between the making of her test and her appearance in the picture, Ethel Kaye, in the eyes of everyone at the studio, had changed. “She has lost something that makes her acceptable,” wired Lehr enigmatically, “and consequently took her out of part this morning after exhaustive consideration. As emergency measure we put Helen Ferguson in part.”334

Helen Ferguson was another veteran of “Lightning” Hopper’s playground, one of the hopefuls who turned up and sat on the extra’s benches, hoping for a job. She was thrown out again and again by the casting director, E. J. Babille, who told her bluntly that she simply wasn’t the type for pictures. She refused to believe him. When she signed a contract for the lead in Hungry Hearts, it was poetic justice that the assistant director should have been the same E. J. Babille.335

Ferguson was delighted with the part, which proved the only major role she was ever to play. “I’m not a Jewess,” she said, “and have always hated the little hump on my nose. I now love it because it brought me the part I love so.”336

In a letter, she assured Yezierska that she would not simply act the part, she would be the part. To this end she went to Temple Street, the Jewish district of Los Angeles, and took a job in a delicatessen. The owner, Abe Budin, was a Russian-Jewish immigrant who lived with his family behind the store. “Warm-heartedly, they asked me to live with them for a while. So I lived with these people and it got so it didn’t smell right any place unless it smelt of gefüllte fish.”337

Abe Budin was given the role of Sopkin the butcher and played it most proficiently.338