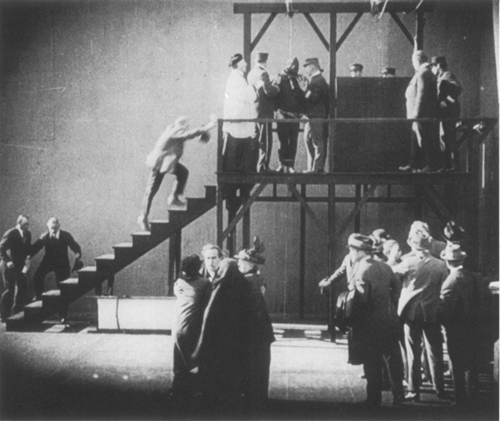

The second film with Thomas Meighan to be shot “up the river” at Sing Sing: The Man Who Found Himself, 1925, directed by Alfred E. Green from a Booth Tarkington story. Its working title was Up the River. (American Museum of the Moving Image)

“THE JAILS of the United States are unbelievably vile. They are almost without exception filthy beyond description, swarming with roaches and body vermin. They are giant crucibles of crime.” These are the words not of a reformer, but of a federal inspector of prisons.1

If prisons were designed to deter crime, those in the United States should have ended it once and for all. Five hundred thousand people were incarcerated; 1,500 died each year.2 Prison conditions were low on the scale of priorities, even in the age of reform, but there was a movement for change, and it was opposed to the idea that severity of punishment was in itself a deterrent to crime.

The moving picture came late to this movement; in any case, it was primarily concerned with sensation. It was a scoop for the early filmmakers to be allowed to film inside a prison, where normally it was forbidden even to take photographs.

In 1912 appeared Convict Life in the Ohio Penitentiary, a three-reeler made by America’s Feature Film Company of Chicago, by special permission of Warden T. H. B. Jones. “The only moving pictures ever taken behind prison walls”3 depicted the Bertillon room and the convict barbershop where heads were shaved, and it pointed out the difference between prisons in Ohio and in other states. Warden Jones believed in educating and elevating the convict, and the film showed the night school, the post office, and the modern cell house contrasted with the 1861 cell block where Confederate prisoners had been confined in the Civil War. The film claimed that in no other prison were the inmates treated with such humane consideration.4

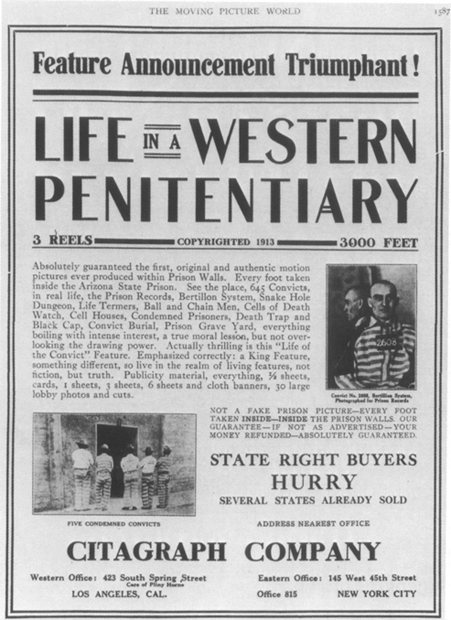

The following year, a film came out advertised as “Absolutely guaranteed the first, original and authentic motion picture ever produced within Prison Walls. Every foot taken inside the Arizona State Prison.”5 Life in a Western Penitentiary was no plea for prison reform, but a revelation of the fate that awaited transgressors of the law: “See the place, 645 convicts, in real life.… Snake Hole Dungeon, Life Termers, Ball and Chain Men, Cells of Death Watch, Condemned Prisoners, Death Trap and Black Cap, Convict Burial, Prison Grave Yard, everything boiling with intense interest.”6

Yet prison reform was a subject treated honorably by many films.

In the West, where proper roads were urgently needed, the overcrowded prisons were an obvious source of labor. In 1906, Warden Cleghorn of Canon City, Colorado, put a group of men into a road camp, promised them parole within a few months, and gave them one unarmed guard as supervisor. This “honor system” worked until the following year, when twenty men escaped. Thomas J. Tynan, who took over as warden, revitalized the idea. His convicts were only too keen to earn the parole and the money, and soon there were 200 working in the “honor camps” all the year round.

From Moving Picture World, December 27, 1913.

Like his friend Judge Lindsey, Tynan was a supporter of the moving picture. He arranged for films to be made at his prison, even though press agents abused his trust with wild stories of actors being shot at by trigger-happy guards.7 He appeared in Selig’s one-reel Circumstantial Evidence (1912), directed by Otis Thayer. Thayer also appeared in it, along with William Duncan and Lester Cuneo.8

Tynan installed projection equipment in the prison. “We found,” he said, “that it helped keep better discipline, for the reason that men who violated rules were excluded from the picture exhibitions for three to six months.”9 In the first two years, his reports showed a drop of 400 in such violations.10

In 1914, Tynan received a visit from Edward A. Morrell of San Francisco, a representative of the California Anti-Capital Punishment League, together with Victor L. Duhem, a motion picture man (of Duhem and Harter), and Miss M. Ewing, a student of sociology at the University of California, Berkeley. Their purpose was to study Tynan’s methods. Duhem filmed the “honor men” at work on the public roads in order to arouse support for Tynan’s humane methods.11

While Tynan was leading the country in prison reform, Thomas Mott Osborne was about to accept an appointment from New York governor William Sulzer as chairman of a State Prison Reform Commission. To find out about conditions, he had himself locked into the Auburn penitentiary for a week as an ordinary convict. This won him derision from the press but the respect and confidence of many of the convicts.

Osborne then introduced what became the first Mutual Welfare League in any prison; the prisoners drafted their own regulations and organized the programs of entertainment in the chapel. He became warden at Sing Sing in 1914. “But under the intense glare of external publicity several disciplinary problems acquired a lurid character and because of a shift in state politics prompted an investigation of the Osborne administration.”12 In 1915, a grand jury indicted him on six counts including perjury, neglect of duty, and sodomy. But the trial was dismissed even before the judge had heard what Osborne had to say. He was cleared of all charges and reinstated in July 1916.13 (He resigned the following October and became openly critical of prisons.)

Osborne was anxious to find employment for convicts who had served their term without a blemish on their records. In 1915, two such men were hired by Carl Laemmle of Universal Pictures. They were given new names, and their past records were forgotten.14

In 1919, in collaboration with Osborne, Edward MacManus produced The Gray Brother. It was directed by Sidney Olcott and written by Basil Dickey. The picture contrasted the old method of treating prisoners with those advocated by the Mutual Welfare League. A poor boy (Sidney D’Albrook) is sent to a traditional jail, with its brutal regime of lock step, prison labor, silence, and torture. A rich boy (Joseph Marquis) is sent to the same prison after its adoption of a humane regime. The two become friends, and when a third friend faces execution, they escape and find the evidence to clear him. For once, the race to the rescue comes too late—an innocent man is executed. The boys, however, are paroled.15

Osborne, now commander of the naval prison at Portsmouth, New Hampshire, visited Chicago in December 1919 and declared that the penitentiary at Joliet was an infamous institution with a cruel and brutal system of management. Ironically, a film of 1914 had presented Joliet as a model prison. A four-reel documentary made by the Industrial Moving Picture Company of Chicago, The Modern Prison, showed the routine and the industry—shoes, chairs, brooms—with emphasis on the “cleanliness” and “humanity.”16 The improvements were said to be entirely the work of Warden Allen, the reform administrator who supervised the film, and his deputy, Warden Walsh.17

Impressed by the example of Warden Tynan and the other officials who used moving pictures to entertain prisoners, the Minnesota State Penitentiary set aside Wednesday evenings for this purpose. The programs corresponded to the releases at the local theatre, except for one or two items Warden Reed did not allow: “We eliminate sickly-sentimental stuff, beer-drinking, saloon-brawling, woman-beating, safe-robbing and blood-and-thunder films in general, and in their place substitute wholesome dramas, interesting travel and educational films, and clean comedies. Shakespearean and other costume plays are very popular.”18

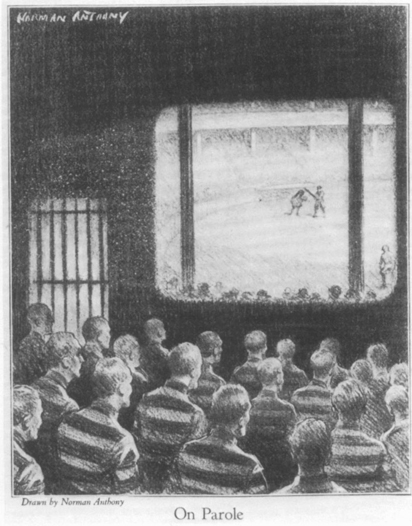

From Photoplay, May 1927.

But nothing matched the courage of Sheriff O’Leary at the Livingston County Jail in Geneseo, New York, “Pat O’Leary’s Hotel” as it was affectionately known. He was an admirer of the motion picture and felt that a night out at a movie theatre would do a lot more good for a man than cramped cells and barred windows. All the men who wanted to work could do so, and earn money, returning to the “hotel” for an evening meal, after which O’Leary encouraged them to go to the movies—on their honor. The sheriff had been operating on a similarly relaxed principle for thirty-five years, and had never lost a man: “No, they never run away. I guess the movies help. It makes them keep good, otherwise they would not get out, and that would be punishment to some who are following a serial.”19

Louis Victor Eytinge, a lifer who ran the film program at the Arizona State Penitentiary in Florence, confirmed the extraordinary effect the films had on discipline. One night, during a screening, all the lights went out. Four hundred inmates had to feel their way back to the cells through total darkness, and yet no one tried to escape, no one tried to settle an old score. Eytinge felt the reason for their exemplary behavior was because the picture programs represented the greatest positive influence in their lives. He had been astonished at the reaction to The Miracle Man, that story of the regeneration of crooks: “If you had seen the men march out of the Assembly Hall, with heads thrown back, moist but exalted eyes, with backbone bulwarked, you would have understood how pictures might accomplish more than all the religious services I’ve ever studied in my twenty years of prison experience!”20

Sing Sing, a mere twenty-five miles from New York City, at Ossining, New York, was a focus of fascination for filmmakers. When Charlie Chaplin visited the prison in 1921, he had the good fortune to travel with Frank Harris, the celebrated author, who wrote a detailed description of the place: “There it lay in the autumn sunshine with the beautiful river and the heights beyond, all bathed in glory; there it lay like a vile plague spot; a great bare, yellow exercise yard; a dozen buildings, the nearest a gray stone building with narrow slits of windows for eyes and bars, bars everywhere. The heart shrank before it.”21

The prison doctor explained that 60 percent of all prisoners had venereal disease of some sort. “We can cure all the diseased here except the dope fiends,” said the doctor, “and we can cure them while they are here, but dope long continued seems to break the will power and once they get out again we find that the addicts go back.”

As they continued their tour, Warden McInerny pointed down to the yard and announced, “The next for the Chair.” Chaplin was greatly affected by the sight of the man’s face: “Tragic, appalling!”

The death house was a bare room with a plain yellow wooden armchair, equipped with bands to hold the arms and feet. The doctor described how he tried to give the signal when the lungs of the prisoner were as empty as possible, to ensure instantaneous death. They put Chaplin in the chair and showed him how everything worked. But Chaplin was haunted by the face of the condemned man: “I shall see that till I die.”

As they walked from building to building, Chaplin was applauded and cheered. An old black man called out, “I’ll be out in 1932. Mind you have a new picture ready, Charlie.”

Chaplin performed tricks with his hat and did his funny walk, and the visit was over. On the journey back, Chaplin remarked, “Someone has said that prisons and graveyards are always in beautiful places.”22

Slapstick was in great demand, but when Dunham Thorp interviewed Sing Sing inmates about their taste in pictures, he found that the most side-splitting of all to them were the supposedly realistic dramas of prison and the underworld. As an example, he cited a Tommy Meighan picture, the interiors of which had been made at Sing Sing itself.23 That picture was The City of Silent Men (1921). It was pure hokum, and yet it was selected by the New York Institute of Photography as one of the best-directed films “because it raises crook melodrama to the level of high art.”24

Promotion for The Quarry—retitled The City of Silent Men. From Photoplay, June 1921.

An adaptation of John A. Morosco’s story The Quarry, it was scripted by Frank Condon and directed by Tom Forman. Jim Montgomery (Meighan) is given a life sentence for a murder he did not commit. Hearing of his mother’s illness, he escapes and after the funeral starts a new life in California. A detective catches up with him, and to avoid identification Jim deliberately shatters his hands in machinery. The detective is so astonished by this heroism that he lets him go. And Jim is eventually cleared.25

The New York Herald admired the film’s documentary quality: “It shows in greater detail than the screen has ever exposed before the process of matriculation at Sing Sing, so that any spectator who later finds himself inducted at Ossining will know precisely the etiquette of the place.”26

While Meighan was filming at Sing Sing, he met the former city editor of the New York Evening World, Charles Chapin, who had shot his wife and been sentenced to twenty years. He had been given the task of editing the prison newspaper, which made him miserable, so he was moved to the garden in the prison yard, which delighted him. He became known as “The Rose Man of Sing Sing.”27 Chapin was proud to meet Meighan, for when his Miracle Man had been shown at the prison, Chapin declared it the best picture he had ever seen.28

At the end of the production, Meighan asked the chairman of the Entertainments Committee what he could give the men. “Meighan,” he replied, “I want a projection machine for the Death House more than anything. They don’t get to see our regular run.” When the machine arrived and the men realized what it was, “they cheered until the walls shook.”29

Sing Sing came first in the prison picture league by showing films—even if mostly educational—every night.30 “I cannot see how we could do half the work that is done without them,” wrote an inmate.31 Some of the more lurid melodramas were booked just for the fun the men derived from kidding them. This could lead to embarrassment. Norma Talmadge’s crook drama Within the Law (1923) was given a preview at Sing Sing, in the company of prominent picture people. A magazine editor reported: “It was odd, the things they laughed at. They laughed when a demented woman trampled upon a flower growing within prison walls … at ‘retirement’ describing a prison term … at Mary Turner who, having married young Gilder, taunted his father with: ‘You took away my name and gave me a number when you sent me up. Now I’ve got your name.’

“The prison laughter! It impressed and depressed us most. Somewhere we remember having read a poem about its hollow sound. It is that … and barren of any ripple of mirth; rather a sudden empty boom, then silence.”32

To deprive a man of his liberty was punishment enough; to deprive him of productive activity was inhuman. So felt the reformers who supported the convict labor schemes, but the American Federation of Labor objected strongly to the unfair competition. Convict labor put its members out of work.

The controversy led to several films. Life in the Ohio Penitentiary (1912) included shots of the “antiquated bolt shop in which the unfair contract labor was in vogue.”33

The Edison Company’s For the Commonwealth (1912) told a simple tale: “An unskilled laborer applies at a shoe factory for employment and is told that he will not do, as men with brains rather than muscle are needed. He returns home, where poverty of the direst sort reigns. His wife berates him for his inability to obtain food for herself and child, whereupon he leaves the house in a rage and does not return. Days afterward the poor woman sees her husband on the street and points him out to the police. The policeman attempts to arrest him, but he snatches the officer’s baton and beats him over the head. At this juncture, another officer rushes up and the man is arrested and later sent to prison for assaulting an officer.”34

Unprotected, 1916. Directed by James Young from a story by Beatrice C. de Mille (mother of the de Mille boys) and inspired by New York Governor Whitman’s criticism of the shipping of prisoners to privately owned farms. Lasky publicity claimed a genuine Southern turpentine farm was used, but it seems more likely it was shot at the Lasky ranch. (Robert S. Birchard Collection)

The wife takes a low-paying job in a shirtwaist factory; meanwhile, her husband and the other inmates are led into a new workshop where they are taught to make shirtwaists on sewing machines. The wife is laid off and is compelled to seek refuge with her child in the poorhouse.

The shirtwaist-makers appeal to the governor, who “realizes that his efforts to ameliorate the condition of the state’s wards has resulted in the impoverishment of its free citizens.” On a visit to the poorhouse, the governor finds inmates who lack shoes and learns that the authorities cannot afford to provide them. This gives him the idea of producing only what the state itself requires. The prisoners are taught shoemaking, and when the husband is released, his newfound skill wins him a job at once, and the picture ends with his reunion with his wife and child.35

For the Commonwealth was valuable propaganda for the National Committee on Prison Labor, at whose instigation it was made. A few years earlier, the Boot and Shoe Workers’ Union had protested against the employment of 4,000 convicts in shoe factories in twelve prisons, dumping 25,000 low-priced shoes on the market every day.36

From Moving Picture World, May 16, 1914. (Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences)

Several states passed laws banning the importation of prison-made goods from other states, though to little effect. Other laws required state governments to order their supplies from prison industries. These regulations were never adequate, either.

Another Edison picture, written by Melvin H. Winstock, a distributor from Portland, Oregon, was based on Oregon’s parole system, which broke up “a particularly obnoxious system of contract labor.” The Convict’s Parole (1912), which featured Marc MacDermott and Mary Fuller,37 opened in the workshop of a state prison, where the convicts are being worked to a frenzy by supervisors. The contractor and the warden are in collusion, but the governor, unhappy about the condition of the men, changes the system to that of parole. The contractors try to force him to change his mind; failing this, they set out to make the prisoners violate their parole. A stool pigeon, sent after the parolees, manages to get three of them arrested and brought back. But one of the convicts overhears the plot and exposes the crooked warden, who is dismissed. The prisoners are released.38

Legislation helped the situation in the North; in the South, the exploitation of prisoners continued unabated.

The Fight for Right (1913), a Reliance two-reeler written by James Oppenheim, a prison labor reform agitator, and directed by Oscar Apfel, was set in a Southern mill town. A knitting company is forced to shut down because its owner, Durland, contracts with a prison to install a knitting plant. John and his brother, Joe, are thrown out of work. Desperate for medicine for their sick mother, Joe tries to rob Durland, but is caught and sent to prison—and put to work on Durland’s knitting machine.39

Prison conditions in the South took a turn for the worse at this period, when convicts were put to work on the roads in chain gangs40 (an abuse which inspired a masterpiece of the early thirties, I Am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang). Edward Sloman’s The Convict King (1915), a three-reeler written by Dudley Glass and made for Lubin, highlighted this evil. It was about two highway contractors, Jared Austin (Melvin Mayo) and Ben Gray (Jay Morley), both of whom use convict labor. A bill is introduced to abolish the system, and Gray assures Austin he will speak against it. A train wreck mutilates Austin’s face beyond recognition, and a convict changes clothes with him. Austin then experiences the horrors of the convict camp at first hand.41

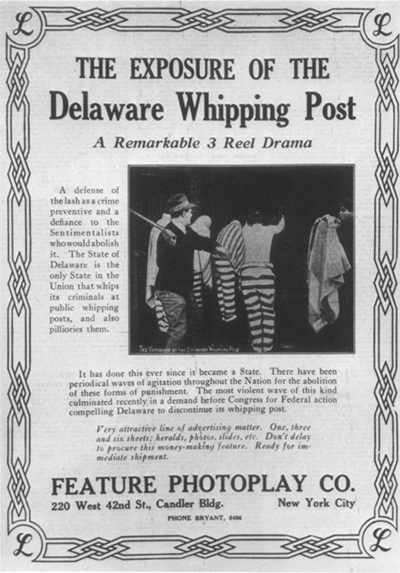

While the majority of prison films supported reform, the Feature Photoplay Company of New York balanced the argument with a three-reeler called The Exposure of the Delaware Whipping Post (1914). “Exposure” was as emotive a word then as now, thanks to the muckraking journalists, but this film was, as an advertisement explained, “a defense of the lash as a crime preventive and a defiance to the Sentimentalists who would abolish it. The State of Delaware is the only State in the Union that whips its criminals at public whipping posts and also pillories them.”42

Delaware had done this from its foundation as a state. Violent protests culminated in a demand to Congress for federal action to compel Delaware to abolish its whipping post. Hence the film. “Very attractive line of advertising matter,” said the film company, showing a photograph of a guard about to lash the naked back of a prisoner.

Delaware did not abolish its whipping post until 1972.

The Whipping Boss (1924) survives in a private collection in England—some of it badly decomposed, but what remains is an astonishing exposé of the convict leasing system. Directed by J. P. McGowan and written by Jack Boyle and Anthony Coldewey, it was copyrighted in 1923, but evidently found some difficulty in getting a release.

McGowan, an Australian, was the husband of Helen Holmes, and the creator of such full-blooded serial melodramas as The Hazards of Helen (1914–17). He was a more than proficient director and while this story is told within the confines of a program picture, it still packs considerable punch. “This picture should do a lot of good,” said Photoplay, “but it isn’t easy to watch.… The story is taken, almost intact, from an actual occurrence.”43

The story was set in Oregon, and the film equates the state’s convict leasing system to slavery. A young drifter, Jim Fairfax (Eddie Phillips), trying to get home to his mother, falls in with hoboes, ignoring advice not to ride the rails through Woodward—“it’s the gateway to the chain gang.” Jim is duly arrested and transported to the Woodward Lumber Co. The state governor has prohibited the use of the lash, but the whipping boss (Wade Boteler) has a new superintendent (J. P. McGowan) who tells him, “You’re not working for the Governor, you’re working for me. Go ahead and use the lash.” The scenes of brutality are mostly missing from this print. But the appalling conditions in the cypress swamps are portrayed with documentary realism. Working up to their waists in water, the convicts are victims of disease as well as the lash. They are observed by Dick Forrest (Lloyd Hughes), head of the local American Legion post, who is so shocked he mobilizes his men. To destroy the evidence of abuse, the lumber camp owner orders the place to be burned down—with the convicts chained to their bunks. The American Legion arrives in time to rescue the convicts who then try to lynch the prison guards. “The American Legion stands for law and order,” warns Forrest, “not the tyranny of the mob.”

It was an ironic line even then—a couple of years earlier, the American Legion had turned out to demonstrate against the showing of the German film, The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, at its American premiere in Los Angeles. The Legion was a symbol of conservatism, and a surprising participant in one of the rare social dramas of the twenties.

THE HONOR SYSTEM Two films of this title, produced within four years of each other, demonstrate the growth in power and sophistication of the social film in America. The first, made by Kalem in 1913, featured Carlyle Blackwell in a study of the effects on a prisoner of brutal treatment and the changes that result from humane conditions. How good it was we shall never know. The picture came and went, submerged in the flood of ordinary nickelodeon fare, and has never resurfaced.

The 1917 version has never resurfaced either, and from what we know about the film, the loss is one of the major tragedies of film history. The New York Times called it “the motion picture pretty nearly at its best,”44 an opinion shared by Variety, which said, “The photography and direction are well nigh flawless.”45

The difference between the two was the difference between a simple piano piece and a full-scale symphony. Of the second version, the New York Dramatic Mirror wrote, “The Honor System is undoubtedly the most powerful philippic against the prison system under which prisoners are held as wild beasts, rather than humans, that has ever been produced. If reform propaganda has a place on the screen, then assuredly this picture deserved first rank.”46

The New York American went as far as it was possible to go: “The Birth of a Nation at last eclipsed.”47

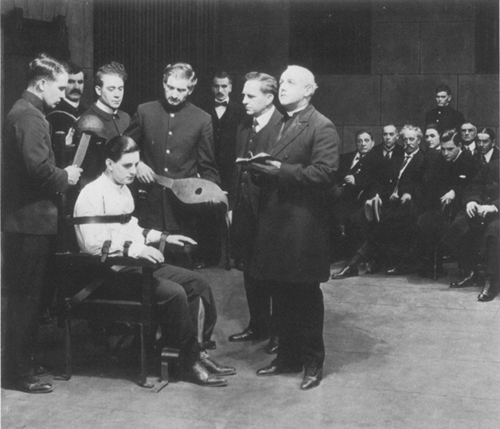

The Honor System, 1917, directed by Raoul Walsh: Milton Sills (center) and Gladys Brockwell.

Written by Henry Christeen Warnack, editorial writer on the Los Angeles Times, and directed by Raoul Walsh, it featured Milton Sills as Joseph Stanton, a New England inventor who develops a scheme to revolutionize wireless telegraphy. Needing money to advance his project, he travels west to a job in the border town of Howling Dog. Mexicans raid the town, backed by Charles Harrington (Charles Clary), an attorney who pulls the strings for certain financial interests. Stanton grabs a horse and sets out for the nearest cavalry post, riding back with them to witness a spectacular cavalry charge.

A prostitute called Trixie (Gladys Brockwell) sets out to ensnare Stanton. During a fight at a dance hall, Stanton is attacked with a knife by her pimp. Defending himself, Stanton kills him. He is arrested, and during the trial, Harrington testifies that the dead man was unarmed. Stanton gets life.

He begins his sentence under the old-fashioned system, which turns convicts into permanent enemies of society. Floggings are administered daily, and the victims are then dragged into verminous, subterranean cells to remain in solitary confinement. Some men go blind; others, unable to bear the torture, kill themselves.

“Serves ’em right,” says the warden (P. J. Cannon). Under his regime, no letters or newspapers are permitted, the food is unspeakable, absolute silence is imperative, and work means hard labor.

The prisoners attempt a breakout. The guards open fire, kill half a dozen, and subdue the rest, but Stanton and his pal Frenchy get away. Stanton delivers a note to the sheriff to hand to the governor:

“For God’s sake, go and see for yourself the horrors of your state prison.

“I escaped from that hell, but I killed a man, and I feel in honor bound to return and serve my term. Imprisonment is just, but I implore you go and end the torture that takes the manhood from the unfortunates.”

When Governor Hunter (James Marcus)48 receives the note, he goes straight to the prison and asks to see Stanton. The brutal warden looks frightened. Stanton had received a flogging to celebrate his return and was then flung into an underground cell. Having lain there for months, he is now a physical wreck. The warden produces a Negro instead.

The governor insists. And Stanton is at last led out, a shockingly emaciated figure, and blind.

Governor Hunter fires the warden and his guards and brings the honor system to the penitentiary. The amazing difference is effected by a single speech in the senate: “Our penitentiary is a disgrace to the State, a disgrace to humanity.” And Hunter produces his exhibit—Stanton, his eyes covered with a bandage.

Stanton works on his invention with the encouragement of the governor. He asks for parole to visit a radio station to test it. The crooked lawyer, Harrington, now chairman of the Board of Pardons, objects. “I’ll stake my life on his return,” laughs the governor. “Will you stake the honor system?” “Done,” says the governor. “If he doesn’t return I’ll move for the ousting of the honor system and the return of the old order of discipline.”

Harrington orders his thugs to trail Stanton, steal his wireless, and prevent his return. They lure him to an address in the slums, where they beat him and lock him up. Frenchy reappears, finds the former warden among the thugs, kills him, and releases Stanton.

Now Stanton races to the station to catch the train on which he had promised to return. But one of Harrington’s gangsters attacks him, and there is a battle royal on the roof of the freight train. Stanton is flung off and stunned. When he recovers consciousness, he has to continue on foot. All night long he staggers onward, determined to vindicate the worth of the honor system. At the prison, the warden is informed that Stanton acted in self-defense at the dance-hall fight and will receive a pardon. But the train arrives with no sight of Stanton. The warden and his daughter, Edith (Miriam Cooper), wait through the night. Not until the early hours does he arrive, in the last stages of exhaustion. He has kept faith with the honor system, but at the cost of his life.

“The death of Stanton revolutionized the prison system, however, and put it on a new basis, where revenge was discarded and love, justice and honor took its place,”49 noted Picture Play.

Although the scenario depended upon melodrama, with a Griffith-style race against time, it was far more significant than the entertainment it was designed for.

In his outline of the story, Henry Christeen Warnack included this foreword: “The Governor of Arizona has earnestly endeavored to bring about sane prison reform in the penitentiaries of his state. Many of the words attributed to him in this story are really from his tongue, and if this should be put on as a picture by a company that wanted to go to Arizona, Governor Hunt would give permission to make views, both in the dismantled prison at Yuma and in the new prison at Florence. He would be willing himself to appear at the meeting of the Board of Pardons and has in mind a worthy man who might be pardoned in conjunction with the climax of this photo-play.”50

Raoul Walsh went to see Governor Hunt and asked to be put in jail for three days to add color to the script. In interviews, this became three weeks51 and he witnesses a hanging for good measure. In his book, he misremembers the story of the film and has Gladys Brockwell playing the warden’s daughter, not Miriam Cooper—an odd lapse, since Miriam Cooper was his wife.52

In her account, Cooper recalled that the picture was shot at both the old and the new penitentiaries in Arizona. The old prison at Yuma had been a horrifying place. As the film showed, prisoners were tied to stakes and flogged, kept in solitary confinement with snakes, rats, and scorpions for company, and treated with the greatest severity.53 But she describes the conditions as though they existed at the time of filming, which did Governor Hunt less than justice; the old Yuma Territorial Prison had already been closed.

The new prison at Florence was in the desert. Fox put up a tent city outside the walls for cast and crew, and Cooper stayed with the warden. It was here that the spectacular Mexican raid was staged. It had absolutely nothing to do with prison reform, but Walsh was enthralled by Mexico and Pancho Villa had recently raided Columbus, New Mexico. Real convicts were used in the jail scenes.

Walsh told me this was the toughest picture he had made in the entire silent period. While in production, Fox sensed something special about it and instructed him to increase it from five to seven or eight reels, which was probably why the Mexicans were thrown in. A late telegram said, “Make it ten.”

One of the most glowing endorsements for the film came from Louis Victor Eytinge, who had been incarcerated at Yuma, and was currently in somewhat happier conditions at Florence. It was also much admired by John Ford.54

Governor Hunt was only too happy to endorse the film. In a letter to William Fox, he wrote, “Everyone in the United States should see your production.… It contrasts the old prison conditions with its inhuman terrorism—its beatings, starvings, murders, suicides—with the modern method which recognizes that every convict has a human soul worthy of redemption.“55

The picture opened at the Lyric Theatre, New York, in February 1917 with a specially composed score and an orchestra of fifty. The New York Times thought it magnificent, but as an indictment of the prison system compared it unfavorably to Galsworthy’s Justice, in which the prisoner was guilty and the administrators of the prison that crushed him were ordinary, decent men. “But The Honor System is an arresting reminder of the medievalism that survives in some of our prisons and will probably not suffer much as propaganda because of the hair-raising melodramatics.”56

At the premiere, the audience applauded titles pleading for the improvement of the prison system.57

Like so many silent pictures, The Honor System began its career with a tragic ending, Stanton dying after returning to the prison. But Fox quickly substituted a happier finale, with Edith nursing him back to health.58 Fox’s publicity men dreamed up a novel ploy: they used one of Henry Ford’s own tricks—the advertising of ideas in newspapers—and made him the butt. Their ad read:

Henry Ford:

With Your Millions

Why Do You Do It?

Starting with praise for Ford’s genius, the ad continued, “In the face of so many fine accomplishments, it seems so wrong that you should leave yourself open to the charge of heartlessness—for no man without a heart could have taken such an interest in all of his fellow men.

“Come to New York now, Mr. Ford, and make public repentance. Bring some of your wealth with you, gather around you, as you did for your peace trip, some of the biggest minds in our nation and say: ‘We failed to end the European horrors, but now we will end the greatest of all horrors here at home.’

“As soon as you have arrived take your party at once to the Lyric Theatre and see the greatest crime of modern society that can be charged up against you and all other wealthy, brainy and influential men and women …

“When you have witnessed this condition we do not believe you will ever again be content and peaceful of heart until you have started some great movement that provides a remedy.”59

One hundred thousand people saw the film during its six-week run, some of them two or three times. Fox had as potentially sensational a film as had Griffith, yet his press agents could not resist the usual publicity nonsense; according to them Governor Hunt reprieved several murderers so they would not be hanged until they had seen themselves on the screen! “All of which,” said Photoplay, “speaks well for the humanitarianism of the Arizona executive and the Fox typewriter soloist.”60

Milton Sills confessed that he had failed to take the movies seriously until he came out to make The Honor System: “That experience convinced me that interesting and artistic things could be done in pictures.”61 Louis Devon, in a 1971 article on Sills, said that he worked with Walsh on the script. The picture still carried a strong memory for Devon: “I was quite young when I saw it and I still remember the impression made upon my young mind by a close-up of maggots crawling on the bread one of the prisoners was given to eat. I think Eisenstein must have been impressed by that close-up too.”62 (A touch of black comedy in the film showed the prisoners sending tiny messages to each other on the backs of cockroaches.)

If Walsh’s astonishing grasp of technique, which he displayed in Regeneration, was as pronounced in The Honor System—and contemporary reviews suggest it was—then the tragedy of its loss is all the greater. But technique was of far less importance in this case than content. As Frederick James Smith put it, “This indeed is the first real attempt of the movies to enlist in a great humanitarian movement. Consequently, The Honor System can be said to have the biggest theme of any screen production thus far.”63

Shortly after this, William Fox altered his policy. Instead of elaborate and costly films on challenging themes, he decided to concentrate on cheaper pictures with more profitable subjects. And for a decade, the company’s name all but disappears from the history of the social film.

Among the horrors in Electric Vaudeville, or amusement arcades, was a series of films depicting in loving detail each stage of the execution of a woman. To see them all, you had to move from one peep-show machine to another. When projectors were developed, the separate scenes were joined together to produce a film which, to the audiences of the time, looked distressingly authentic.

Adolph Zukor recalled that another of the early films showed the hanging of a Negro in a Southern jail, omitting no ghastly detail. “For years this piece of tainted celluloid dodged through the country just ahead of the sheriff and the police.”64

And the Law Says, 1916. A law student (Richard Bennett) has an affair which results in an illegitimate child. He runs away from his responsibility. Eventually, he becomes a judge and one day, not realizing his own son stands before him, he sentences him to death. Here, the innocent son (Allan Forrest) awaits execution. (Robert S. Birchard Collection)

Such films were made for their shock value and their commercial potential, and execution scenes flourished long after the censorship which was supposed to abolish them.

“Pictures showing the harrowing details of an execution by hanging ought never to be passed by a board of censorship,” said W. Stephen Bush. “It is no excuse to say that the execution was part of a dream. To the audience it is frightfully real, nevertheless. It is bad enough to flash a view of a gibbet before the eyes of an audience and to indicate, however dimly, that a human being is about to be done to death. To revel in such details and to stretch them out with painstaking care and an evident morbid relish, is an intolerable offense. What excuse can an exhibitor make to the outraged parents of boys and girls who are shocked and sickened by such exhibitions?”65

One fervent opponent of capital punishment was Hal Reid. His one-reel Vitagraph drama Thou Shalt Not Kill (1913) had a twist calculated to disturb every woman in the audience. It opened with a strikingly lit scene in which a mother (Julia Swayne Gordon) defends herself and her child against her husband: “If you ever treat me like that again I’ll kill you.” The child remembers this when the husband is accidentally shot while out hunting, and her innocent testimony puts the mother in the death house. But she is pregnant, and the governor rules that the state cannot take two lives for one. The child is allowed to be born, and during the delay the shooting mystery is cleared up.

Two years later, Reid made a five-reeler with the same title for his own Circle Film Corporation. Its publicity exploited the Leo Frank case (see this page), but it was actually a story of a boy in the Kentucky hills, the son of a judge, who is arrested for killing a deputy. A confession from the real killer reaches the boy’s father just after his execution.66

The Gangsters of New York (1914) was also intended to evoke anti-capital punishment sympathy. While Biff Dugan (Jack Dillon) walks to the electric chair at Sing Sing, the sister of the chief gangster dies of consumption and a broken heart. “The actual death of the convict by the electrical current is not shown,” said Variety, “but it goes as near to it as the prison warden dropping the handkerchief, which leaves little surmise.” Yet Variety said that the film “points a finger at capital punishment as the possible end to more crime.”67

A proprietor showing this film set up a mock “electric chair” complete with model victim outside his theatre and employed a barker to urge people to see the film. A crowd gathered, and the proprietor was arrested for disorderly conduct. “We doubt whether half a dozen men in the business could be found willing to stoop so low, but of course even one is enough to harm the whole industry.”68

A two-reel melodrama called The City of Darkness (1914) was made for Thomas Ince by Walter Edwards, who also played the lead as the governor. Formerly a district attorney, the governor has made a deadly enemy of a ward boss (Herschel Mayall) by sending his son to the chair for murder. The ward boss seizes the chance for revenge by framing the governor’s brother (Charles Ray). He is found guilty and sentenced to death. The ward boss visits the governor to extract the last ounce of pleasure from his predicament and makes him suffer more by telling him his brother is innocent. The governor struggles with the boss and then tries to prevent the execution.

“The innocent man is shown making his final preparations for death, while the governor is speeding to a form of rescue that has suggested itself to his acute intelligence. The boy is led into the death chamber and placed in the chair. The governor dashes into a tremendous building filled with machinery—it is possible to shut off the power that lights the city …

“Views are flashed of varied action in high and low society as the whole city is plunged into darkness. The suspense is all the more drawn out because the telephone lines to the prison are cut off to prevent a flood of morbid messages. But the boy is saved and justice is done in the end.”69

The race to the rescue was already a standard feature of such films. It would make fascinating comparison to Griffith’s in The Mother and the Law, which eventually formed the modern story of Intolerance (1916), his epic of injustice through the ages. The Mother and the Law was also melodrama, but the story was propaganda against capital punishment. For once there was no doubt that it was intended as such.

Griffith undertook research trips to prisons, with cameraman Billy Bitzer and his assistant Karl Brown. At San Quentin the party was shown a room where ropes were stretched with 150-pound sandbags before being used on the gallows next door.

“I was all prepared for what I was to see,” wrote Brown, “because everyone knows that gallows are painted black and that there are thirteen steps.

“To my astonished disbelief the gallows was painted a baby blue. It was much bigger and higher than I had expected, all of twenty feet from the floor to the top crossbeams.”70

The warden took them underneath to explain the mechanism. “See these four cords? They’re heavy, hundred-pound-test-fishline and they run through a pulley to this fifty-pound sandbag. Cut the cords from above, the sandbag drops, and here—I’ll show you.”

“He pulled the cord by hand. The latch released the trap, which was made of heavy, laminated wood. This let the trap swing heavily to the opposite side, where it clanged loudly into another spring latch. That sound, in the bare, echoing room, was ghastly. I had never heard death proclaim itself in such a loud, definitive way.”71

Of the four strings, which were accompanied by razor-sharp knives, only one was connected to the trip weight. Four men operated the knives, but they could not see the prisoner and they never knew which cord sprung the trap. It was the equivalent of the blank cartridge for the firing squad.

Griffith asked about a last-second reprieve: “I didn’t see any phone on that gallows.”

“You didn’t because there isn’t any. We wouldn’t take a chance on not hearing a phone ring at a time like that. We have a direct line held open to the governor’s mansion all during that last twenty-four hours; the instant a call comes through, the switchboard hits a big alarm bell that sounds all through the prison. The instant that bell sounds everything stops.”72

Griffith does not ignore the telephone, but because it would have ruined his race to the rescue, he has the warden reject the message and proceed with the execution. His scaffold was built under the supervision of Martin Aguerre, for twenty years warden at San Quentin. Since he had officiated at numerous executions, he supervised this one, too.73 Griffith was criticized for his race to the rescue; despite the fact that it became one of the most highly praised sequences in film history, critics dismissed it as mere melodrama.

Frame enlargement from Intolerance, 1916. A last minute rescue. The scaffold was constructed under the direction of a former prison official.

He justified it by referring to the recent Stielow case. “Stielow was convicted of a murder and sentenced to die,” said Griffith. “Four times he was prepared for the chair, four times he and his family suffered every agony save the final swish of the current.

“What saved him was exactly what saved ‘The Boy’ in my picture; the murderer confessed, the final reprieve arrived just as the man was ready to be placed in the chair, his trousers’ leg already slit for the electrode.”74

Since the boy in the film is a gangster to begin with, his near execution is not so obvious a case of intolerance as it might have been had Griffith taken the Leo Frank case as a model. But then this story began life under another title (The Mother and the Law). To make it more relevant to the new title, Griffith calls the prison “a sometimes House of Intolerance” and has the boy “intolerated away for a term.”

“Griffith’s realization of ritualized death in the finished film remains to this day as powerful as any such sequence ever done in the movies,” wrote Richard Schickel, “precisely because the detailing is so lavish, so profoundly felt.”75

The People vs. John Doe (1916), made by Lois Weber, was described by the New York Times as “the most effective propaganda in film form ever seen here.”76

The story was actually a combination of several murder trials, with the essentials taken from the Stielow case.* A protest against capital punishment, the film was also a protest against the system that permitted the state to sentence a man to death on circumstantial evidence. “The horrors of the third degree are vividly portrayed and it is shown how it is possible that alleged confessions can be tortured from a man who is really innocent but will swear to anything so as to be let alone.”77

The film had the backing of the Humanitarian Cult, whose founder, Mischa Appelbaum, gave a speech at the end of it emphasizing the theme. Variety said the exhibitor who could not secure local endorsements on this film had better go out of business.78

Under the title God’s Law, the film was shown to Pennsylvania’s House of Representatives as the state legislators debated the abolition of capital punishment.79

Even supporters of capital punishment were disturbed by the use of the electric chair, not for any moral reason, but because it was possible for the victim to survive even so massive a surge of electricity. In The Return of Maurice Donnelly (1914), a Vitagraph three-reeler directed by William Humphrey, a convicted man is electrocuted. The film shows a dead rabbit being resurrected through an electric shock. “Then the corpse is brought back from the electric chamber, quite dead and cold, and by the tremendous voltage likewise brought back.… This is without doubt the best part of the play, for good lighting effects make the intense spark, the bare torso and the more or less breathless expectation, the one really great moment of the play.”81

Dorothy Davenport (Mrs. Wallace Reid) appeared in The Girl and the Crisis (1917), a five-reel Universal, written and directed by William V. Mong. A governor is shot and the murderer apprehended and sentenced to death. The young lieutenant governor, now in the governor’s chair, is assailed by both sides and eventually commutes the sentence at the expense of his own political future.81 But he does so too late—the condemned man’s agony causes him to die of a stroke.

One ardent opponent of capital punishment was Maibelle Heikes Justice, a short-story author and screenwriter who worked for many picture companies including Selig, Lubin, Metro, and Essanay and who was the daughter of a well-known judge.82 She wrote Who Shall Take My Life?, which was made in 1917 by Selig’s leading director, Colin Campbell. Once again, it was the story of a man convicted by circumstantial evidence. After the execution is carried out, the warden receives word that the victim has been found alive, working as a prostitute in a Western city.83

The subject of capital punishment became merely a device to conclude thrillers during the twenties. There were so many races to the rescue in the style of Intolerance that they became parodies of themselves. The Last Hour (1923) was given this dismissal by Photoplay: “Saved at the eleventh hour. From the hangman’s noose. With the entire audience applauding the hangman, and cursing the automobile that makes such good time on the roads.”84

B. P. Schulberg’s Capital Punishment, 1925. Clara Bow and George Hackathorne as the innocent man condemned to death. (George Eastman House)

At least one commercial film did set out to preach against capital punishment. In 1925 B. P. Schulberg’s Preferred Pictures produced Capital Punishment, which had the advantage of two of the silent cinema’s most seductive actresses, Clara Bow and Margaret Livingston, and a story by Schulberg himself.

The picture was inspired by the Leopold-Loeb trial.85 In May 1924, eighteen-year-old Nathan Leopold and Richard Loeb, seventeen, two brilliant college students who were the sons of millionaires, committed the “perfect” (and motiveless) murder, killing a boy of fourteen and attributing it to kidnappers. When the body was discovered, Leopold’s glasses were found nearby and Loeb cast suspicion upon himself by his remarks. At the trial their lawyer, Clarence Darrow, pleaded for life sentences rather than execution and succeeded.86

In the film, welfare worker Gordon Harrington (Elliott Dexter) bets his friend Harry Phillips (Robert Ellis) $10,000 that he can have an innocent man convicted of murder. He arranges with Dan O’Connor (George Hackathorne) to take the blame for a murder that will never occur. At the right moment the hoax will be disclosed and capital punishment will be discredited. He sends Phillips on a cruise and makes it appear that he has been murdered by O’Connor. O’Connor is convicted and sentenced to death. Phillips returns unexpectedly and, in an argument, Harrington accidentally kills him. His fiancée persuades him not to report the killing to the police. O’Connor is about to be executed when the girl changes her mind and turns Harrington in.87

B.P.’s son, Budd, in his book Moving Pictures, recalled a reprieve coming too late. According to him, when exhibitors pleaded for a happy ending, B.P. said, “If you’re going to make a movie attacking capital punishment, then goddamn it, attack it!”88 This scene was not the ending, however, but a prologue.89

The release coincided with a campaign by Bernarr MacFadden’s newspaper, the New York Graphic, for the abolition of capital punishment in New York.90 Given the title, Picture Play thought any expert fan would be able to tell the story: “There is the innocent boy who is sent to the electric chair; there are the trusting friends, the staunch girl and the surly influences. And, if you will credit it, there is the old race with death with the pardon arriving just as— But oh! my goodness, when will these governors learn to use the telephone?”91

Warden Lawes arranged a showing at Sing Sing, and a woman journalist from Picture Play went with the party: “They showed the film in the prison chapel, and the men seemed to love it. All the comedy scenes went over wonderfully, but when there was a serious title—‘May God have mercy on our souls’—just after the warden had allowed an innocent man to be electrocuted, the convicts roared with laughter.”92

* Its working title was The Celebrated Stielow Case.