From Moving Picture World, October 19, 1912. (Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences)

“Probably no other evil of modern industrialism has had a more devastating effect upon the home and family than child labor,” said Judge Ben Lindsey.1 But his attempt to impose Colorado’s child-labor restrictions on a local cotton mill led to the closing of the factory.2 The families who depended on their children’s earnings and were now reduced to the bread line did not thank the judge for his moral rectitude. It is significant that his attempt to make a film on the subject did not succeed. Relatively few films on this most provocative of topics were produced, perhaps because of this very paradox: the children working down the mines or in the factories were usually there with the knowledge and complicity of their parents.

By 1900, with more than 1,790,000 child laborers in America, most industrial states had enacted some form of protective regulation, but few of them had enough power to be effective.3 The problem was at its worst in the South.

Carl Laemmle, president of the Universal Film Manufacturing Company, took frequent tours among small-town exhibitors, and it was while visiting the Mississippi Valley that he became aware of the widespread use of child labor. The result was a two-reeler called The Blood of the Children (1915), written by Bess Meredyth and directed by Henry MacRae.

Shot partly in a cotton gin, the film was an exposé of conditions in cotton factories, both in the South and in New England, where lint was a constant hazard to health. William Clifford played a senator ready to vote for a child labor bill, whom two mill-owners (Sherman Bainbridge and Rex de Rosselli) attempt to buy off. Overcoming his anger, the senator tells them, in a series of flashbacks, of his days as a factory employee and later owner and of the number of men, women, and children who were injured each year or who died from disease. The mill-owners are won over to his side, and they put the bribe money into a fund to support the passage of the act.4 Prints of the film were sent to Atlanta and New Orleans for exhibition to cotton men, many of whom admitted that the conditions shown in the film were all too true.

The fight against child labor had been initiated largely by settlement workers. In 1903, Lillian Wald put forward a proposal for a children’s bureau. President Theodore Roosevelt invited her to Washington, but nothing much happened until 1909, when Roosevelt called a White House Conference on the Care of Dependent Children. Miss Wald testified before a Senate committee, comparing the treatment of children to that of pigs. A bill drafted by Wald and Florence Kelley of Hull-House eventually received President William Howard Taft’s signature in April 1912, but it achieved little. The problem persisted, and in 1920 one of the most famous settlement workers made a film on the subject.

Sophie Irene Loeb, who had been brought to the United States from Russia at the age of six, was a reformer and sociologist who, like Jane Addams, succeeded in bettering the society in which she lived.5 She is remembered in particular for her work in connection with child welfare. Besides books, she also wrote a film called The Woman God Sent (1920) dealing with the efforts of a young woman (Zena Keefe) and a senator to enact a law forbidding child labor in factories. It was directed by Larry Trimble.

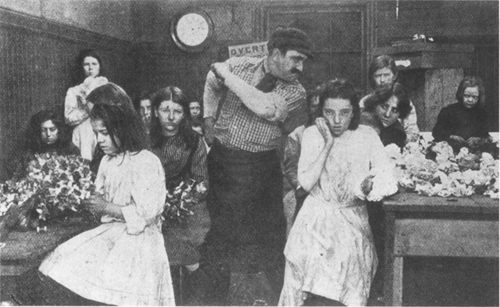

Children forced to work at making artificial flowers: Child Labor, 1913. From Moving Picture World, January 18, 1913.

“The hammer of propaganda is skillfully wielded,” said Photoplay, “for the picture is well told and holds your interest.”6

The fact that child labor should still be an issue at the end of the Reform Era is an indication of the strength of the opposition. The industrialists had found an all-purpose answer to their critics; they described the issue as “a Trojan horse concealing Bolshevists, Communists, Socialists and all that traitorous and destructive brood.”7

Back in the 1890s reformers thought that photographs showing children at work would arouse so much sentiment that none but the most rabid capitalist would stand in the way of a Constitutional amendment. They were fortunate to acquire the services of a great photographer, Lewis Hine. As staff photographer for the National Child Labor Committee (NCLC), he smuggled his camera into factories, risking violence from foremen and mill-owners, and produced a series of brilliant still pictures.

“Winning the confidence of the children,” wrote Robert Doty, “he would interview them while scribbling notes on a pad inside his pocket. These would be rewritten later, in a legible form.… These photographs and information formed the backbone of the publicity efforts of the National Child Labor Committee. They were used to illustrate booklets, posters, magazines and even as source material for several films.”8

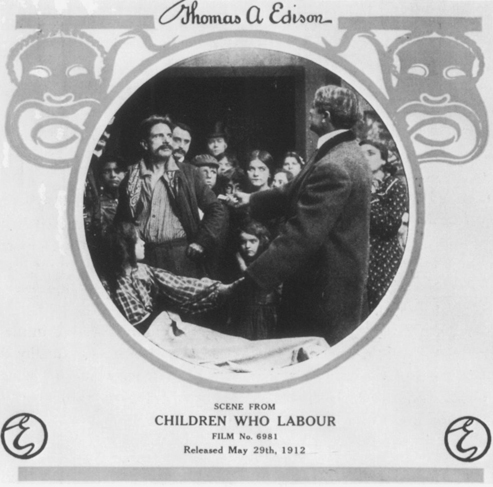

CHILDREN WHO LABOR One of these films was Children Who Labor (1912), made by the Edison Company in cooperation with the National Child Labor Committee and highly praised for its artistry. It featured the Flugrath sisters, later known as Viola Dana and Shirley Mason, and it was filmed in Paterson, New Jersey, and at the Bronx studio.9 A print survives at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, confirming that a great deal of care and skill went into it. But it cannot compare with the work of Lewis Hine.

It is an unlikely but nonetheless compelling little melodrama, with good lighting and inventive art direction. The playing is unrestrained, although Viola Dana is both natural and beautiful. The film opens with a title, “The appeal of the child laborers,” and an allegorical double exposure shows the figure of Uncle Sam looming over lines of children filing into a factory beneath a lowering sky. They raise their hands beseechingly; Uncle Sam takes no notice. Over the factory appears the word “GREED.”10

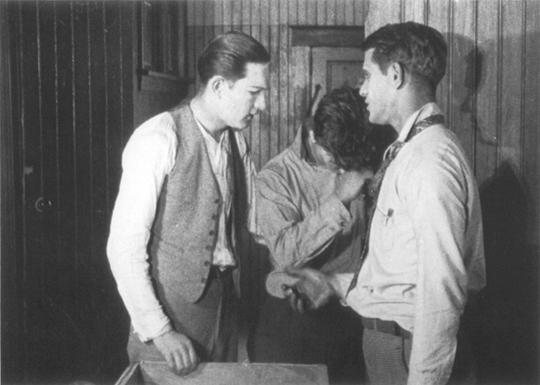

John Sturgeon (left), Robert Conness (right), and Viola Dana (center). From Edison Kinetogram, London Edition, May 1, 1912. (David Robinson)

Outside the gates, an Italian (John Sturgeon) vainly tries to get work. No men are wanted; the foreman is far more interested in his daughter. Members of the NCLC endeavor to persuade Hanscomb, the factory owner (Robert Conness), to abolish the evil, but he refuses. Nor will he listen to the Italian who pleads with him when he drives up to the factory. The daughter is put to work.

Hanscomb’s wife (Miriam Nesbitt) takes a train journey with her daughter Mabel (Mason). Playing on the observation platform, the girl drops her handkerchief and steps off the train to retrieve it. The train pulls out without her. She is stranded in the town where the Italian lives, and he and his wife give her shelter. Her mother is frantic, but not even a detective can locate the child. The needy Italian reluctantly sends Mabel to the factory along with his own child (Dana). Hanscomb becomes an even more ruthless employer and expands his empire—buying another factory, the very one in which his daughter is employed. During a visit to the factory by the Hanscombs, Mabel collapses and is rushed home on a stretcher. Kindhearted Mrs. Hanscomb calls on the Italian with sustenance and discovers her daughter. The child refuses to greet her father until she has berated him for employing children. Hanscomb is converted and we see grown men taking over the work, but the film ends with a reprise of the opening scene, Uncle Sam now looking with concern at the upraised arms.

“Sincerity glows in every one of its scenes,” said Moving Picture World. “This reviewer has heard audiences receive good pictures before, but he has never heard the applause that this picture got.”11

THE CRY OF THE CHILDREN In 1912, a presidential election year, the Thanhouser studio released a film which was described as “the boldest, most timely and most effective appeal for stamping out the cruelest of all social abuses.”12 Woodrow Wilson, the Democratic candidate, cited it as an instance of the outrages permitted by the Taft administration, even though Taft’s signature on the Child Labor Bill was hardly dry.13

Thanhouser used the words of Theodore Roosevelt, who had formed the break-away Progressive party, in the advertising, suggesting he had endorsed the film: “When I plead the cause of the overworked girl in a factory, of the stunted child toiling at inhuman labor … when I protest against the unfair profit of unscrupulous and conscienceless men … I am not only fighting for the weak, I am fighting also for the strong.”14

The Cry of the Children, seen today, is a primitive film. Conceived in the direct-to-camera style of 1912, it nonetheless achieves a kind of elegiac quality through its use of the poem by Elizabeth Barrett Browning15 from which it takes its title and the solemnity with which its players conduct themselves. The poem does not dictate the story, but a prologue illustrates the lines:

The young lambs are bleating in the meadows,

The young birds are chirping in the nest …

But the young, young children …

They are weeping …

In the country of the free!

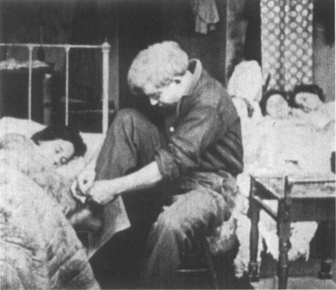

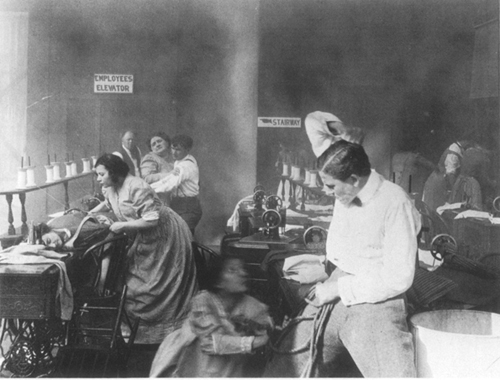

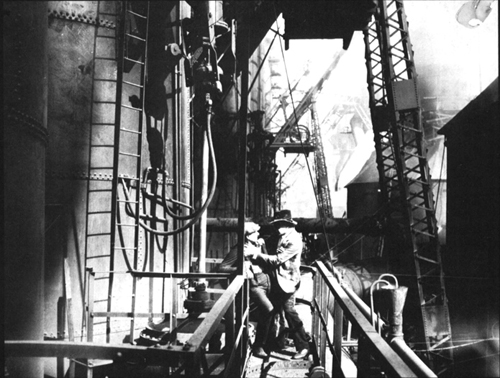

The day starts before dawn at the millworkers’ home. Father wakes first, and we see him tying his boots by candlelight. The wife and two of the children are careful not to wake little Alice, who is to be kept from “the shadow of the factory.” After a meager breakfast, they go to work and are checked by the supervisor at the gate. The mill-owner and his wife leave their palatial home in a luxurious car for a tour of the factory. One glimpse is enough for the wife; she retreats, deafened by the roar of the machines.

At the end of the day, Alice takes her bucket to the stream. The owner’s wife sees her from her car and chats to her. Enchanted by her radiant good nature, she offers to adopt her, but Alice loyally refuses to leave her family.

The millworkers strike for a living wage, but the owner stands firm and, after months of privation, the workers are defeated. The owner gathers his supporters for a celebratory supper and reads them the news: STARVATION WILL SOON FORCE MILLWORKERS TO ABANDON STRIKE—Large Families Endure Heavy Hardships—Children Cry for Bread.

The owner is congratulated.

Weakened by hunger, the mother collapses and little Alice is obliged to go to work in her place. “All day she drives the wheels of iron.” The mother’s illness worsens, and to help her family Alice offers herself for adoption. But now the owner’s wife is repelled by the child’s haggard appearance.

“It is good when it happens,” say the children,

“That we die before our time.”

Exhausted by overwork, Alice collapses at her machine. The supervisor lays her on a chair in the owner’s office. Her father is summoned to remove her.

From the sleep wherein she lieth none will wake her Crying, “Get up, little Alice! it is day.”

After the funeral, the family encounters the owner and his wife in their car. The wife is full of tearful self-reproach. In an astonishing series of dissolves, unique for their time, the mill-owner and his wife are linked in responsibility to the factory and the wage-slaves who work in it yet are shown to be as touched by grief as the bereaved family itself: the husband takes the wife’s hand, mix to a long shot of a factory complex, to the supervisor pushing Alice back to work, and her collapse, to the father and mother at the graveside, and back to the owner holding his wife’s hand. She breaks free and, choking with sobs, sinks to a chair. And then we mix back to the long shot of the factories.

Intended to form part of a series called Can Such Things Be?—which was not completed—The Cry of the Children is an unusually restrained and moving film for 1912. The performers are comparatively natural except for Marie Eline, “the Thanhouser kidlet,” as little Alice.16 She hops, skips, and jumps until her demise at the factory comes as a welcome relief.

The Cry of the Children would be called naïve today, and with justice. Its treatment is sentimental, its story only a variation of the hoary melodrama of the mill girl who resists the owner’s advances until she must yield in order to buy medicine to save her mother’s life. Yet it carries evidence of a more creative mind than one normally encounters in a picture of 1912. The director (who is unknown, alas)17 used a real mill for the interiors (which tend to be underexposed as a result). One or two shots carry the influence of Lewis Hine, though they lack his pictorial flair. And while the cutting between poverty and luxury is as obvious as in Edwin S. Porter’s 1905 The Kleptomaniac, the editing is handled with a trifle more skill than in most productions of the time.

W. Stephen Bush considered the film so important he devoted a lengthy essay to it in Moving Picture World:

“More than two generations have passed away since Elizabeth Barrett Browning told of ‘the children weeping ere the sorrow comes with years.’ Since that time, great efforts have been made by many good men and women to stop this evil. The best that had been accomplished was a law establishing a Federal Bureau, which could do nothing but investigate conditions. However, it could arouse public sentiment through the publication of reports. We are glad to say that the Thanhouser picture will accomplish the same results … the arousing of public indignation. The pictures are admirably conceived, do not at any time go beyond the line of probability and bring home their lesson in a forceful but perfectly natural and convincing way.… While the picture skillfully paints the extremes of our modern social life, it has steered clear of the fatal error of the old time melodrama in which, instead of human beings, the spectator was compelled to see a set of angels and a set of devils. The Cry of the Children makes it plain that the mill-owner is as much a creature of circumstances and surroundings and economic conditions as the laborer.

Frame enlargements from The Cry of the Children, 1913. Before dawn, father (James Cruze) rises.

Marie Eline as Alice at work in the mill. Frame enlargement from The Cry of the Children, 1913.

Alice (Marie Eline) collapses at the mill. (Gerald McKee)

“The report of the Federal Bureau will be read by hundreds, at best, while the picture will be seen by millions … we will confess ourselves much mistaken if The Cry of the Children will not serve as a valuable campaign argument long before the votes are counted in November.”18

Five times the Socialist candidate for president, Eugene Debs seemed within reach of the White House in 1912. A few years later he was in jail. While the fire of socialism swept over Europe, its flames found damper fuel in America. The working class was divided. American workers (many of them foreign-born), alarmed by the increasing influx of immigrant labor, formed trade unions to protect their own positions, unions which were not allied to a political party, as in England. Samuel Gompers, British-born head of the American Federation of Labor, rejected socialism and depended on the self-interest of the workers to improve conditions.

Socialism and anarchism were confused, intentionally by the press, unintentionally by the public. And whenever the workers resorted to violence, they made it easier for the authorities to act against socialists, anarchists, and unionists alike.19

In April 1911, John J. McNamara, secretary of the International Association of Bridge and Structural Iron Workers, and his brother, James B., were charged with dynamiting the Los Angeles Times Building on October 1, 1910. Twenty-one people were killed.

The American Federation of Labor produced A Martyr to His Cause in 1911 to defend the McNamaras; it depicted John as the innocent victim of open shop militants and had him pleading to the public “to suspend judgments … until opportunity for a fair and full defense had been afforded.”20 The film attracted large audiences until the McNamaras pleaded guilty. After the trial Clarence Darrow, their attorney, was himself tried—and, after two trials, acquitted—for attempting to bribe a juror.

The McNamara trial was worked into a film called From Dusk to Dawn (1913) in which Darrow played himself. It was written and directed by Frank E. Wolfe, whose ambition was to “take Socialism before the people of the world on the rising tide of movie popularity.”21 Produced by the Occidental Motion Picture Company of California, the four-reeler was advertised with a significant slogan: “85 Per Cent of your Theatre-Goers—the Numberless Working Class—Will Want to See This Picture.”22

The main part of the film dealt with Daniel Grayson, a union man forced to leave an ironworks, who is involved in strike, riot, and explosion. Eventually, he is nominated for governor on the working-class ticket. All parties unite to defeat him. Then comes the “conspiracy” trial. With Darrow found not guilty, a wave of enthusiasm carries Dan to victory.23 There was irony in this, for Job Harriman, running for mayor of Los Angeles on a Socialist ticket, was soundly defeated as a result of the McNamara case. Also defeated was Frank Wolfe, running on the same ticket for city councilman.

The nickelodeon was not a forum for politics, and films on working-class themes were rare. Tom Brandon has established the fact that of 4,249 films reviewed in the trade press in 1914, a mere nineteen were directly political. Seven were prolabor (one being Germinal from France), six antilabor, and six “populist.”24

The populist films have been mistaken for socialist tracts because populism embraced certain socialist ideas. Formed in 1892, the People’s party was a coalition of those united by fear of big business, disgust with corruption, and sympathy for labor. America was divided into “producers”—those who worked with their hands—and “nonproducers.” But populists did not want the means of production owned by the state; they cherished the system of free enterprise and opportunity for the individual. And they prided themselves on being “home-grown”—not like that imported doctrine of socialism—and were distinctly unfriendly to immigrants.25 Populist films about poverty or capital versus labor refused to condemn the system but blamed the grafting politician or the selfish millowner. Once the villain was removed, the sun came out and the workers marched happily back to their machines.

Films which adopted a socialist view were few and far between. The miracle was that any were made at all.

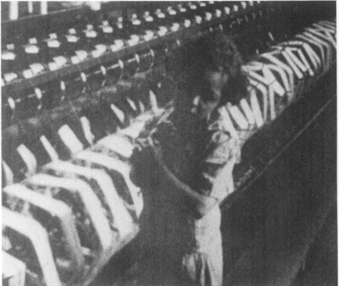

The Eclair production Why? (1913) asked unpalatable questions: “Why do we have children at hard labor?” “Why do we have men who gamble at the race track?” “Why are trains run so fast that fatal accidents occur?” (It had been revealed, in 1912, that railroad travelers had sustained more than 180,000 injuries—10,000 of them fatal—in a single year.)26

H. C. Judson wrote that it was not within the province of a reviewer to discuss politics, yet the exhibitor had to take careful account of them, for what might appeal in one neighborhood might infuriate another. He dare not wholly commend this film.27

“The motive of the story,” wrote another critic, “is to show the manner in which capital and labor clash. Much of it is socialistic doctrine, strongly presented … perhaps too strongly for many audiences.”28

The picture employed photographic trickery in the French style. In a dream, the wealthy hero travels the word and is struck by the hardship of labor. He sees children working on a factory treadmill, women working at half pay and using blood to make red thread, horses being killed because their owners would not insure them. To demonstrate that it is impossible to kill capital, he shoots the child-labor employer who is transformed into a bag of gold. The hero is invited to a feast; working men break in, demanding a seat at the table. Frightened capitalists rally round the generals as they shoot the people, who fall beside the food-laden table.

“Following this comes the most sensational picture we have ever seen; it is nothing less than the burning of the Woolworth Building and all the other buildings in the lower part of Manhattan Island. They are shown all going up in red fire and it is indeed a tremendous spectacle.”29

The Socialist allegory, Why?, 1913. Child laborers on the treadmill of the Almighty Dollar. (Robert S. Birchard Collection)

H. C. Judson did not think the picture taught anarchy. It was only a dream, after all: “Things are bad enough, but they are not as this picture shows them.”30

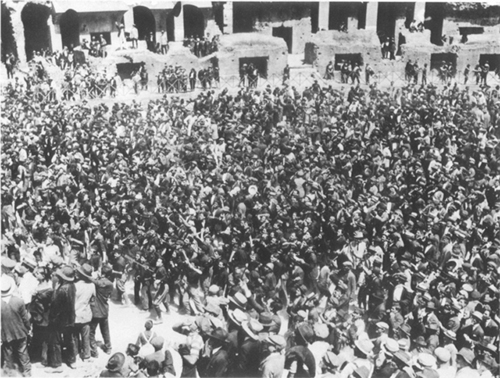

In 1914, a multireel spectacular appeared from an independent company called the United Keanograph Film Company of Fairfax, California. Entitled Money, it was said to have 2,000 extras. James Keane, president of the company, wrote the scenario and directed the picture. George Scott was the cameraman;31 the picture was shot largely on location.

In a scene filmed at the Union Iron Works in San Francisco, Baroness von Saxe, a member of an aristocratic German family, appeared with her daughter, Leonora. Her unlikely interest in the cinema arose because her father, a general, was the first nobleman in Germany to install a projection machine in his Schloss. The baroness explained to the press that some of her happiest moments were spent in the theatre watching American films, so she was only too pleased to distinguish another with her presence. Had she been aware of the content, she might have hesitated. Announced as a six-reeler, advertised as a seven-reeler, but reviewed as a five-reeler, Money was described as “the frankest kind of socialism.”32 It was, perhaps, inspired by Why?, for one of its big scenes had the starving workers storming a banquet.

The melodramatic coating to the political pill dealt with the pursuit of a stenographer by the youthful partner in a steel works, a pursuit which involved mistaken identity and a chase by car and boat. But because it was a political film, there were three villains: the capitalist who reduces wages, gives banquets, and oppresses the poor; his young partner; and an anarchist who aids and abets him. The hero was a poor worker, who took the daughter of the capitalist to see poverty in all its squalor and misery.

“When Keane hired 2,000 ‘roughnecks’ to storm the palace of Croesus, at which was being held the Million Dollar Dinner,” said Moving Picture World, “he wanted the consequent battle between them and the police to look like a battle.… One of Keane’s jokeful friends ‘tipped off’ the police that an attack in all sincerity was being made. The effect of a hundred coppers wielding clubs on 2,000 underworldlings … can be imagined.”33 A typical piece of publicity nonsense of the time, which undermined the talent Keane must have had as a director, for the action had “snap and fire.”34

Money was first shown at Grauman’s Savoy Theatre in San Francisco on September 2, 1914. Among the audience of 1,500 was a Judge Lawlor, who declared: “The most powerfully written, intensely acted and photographically perfect picture I have ever witnessed.”

Other local personalities included Andrew J. Gallagher, president of the San Francisco Labor Council, who called it “the greatest labor picture ever thrown on the screen. Every union man SHOULD and I know WILL see it.”35

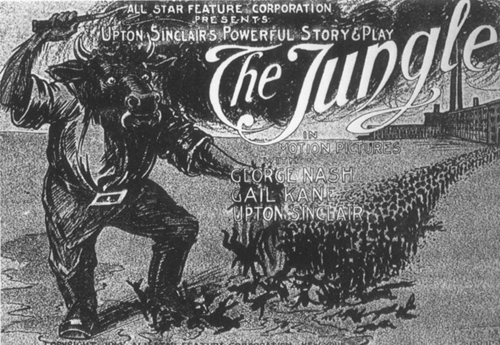

UPTON SINCLAIR What did socialists think of the American motion picture? Upton Sinclair left his thoughts on the subject in a letter to Nicolai Lebedev of Proletkino, Moscow: “The moving pictures furnish the principal intellectual food of the workers at the present time, and the supplying of this food is entirely in the hands of the capitalist class, and the food supplied is poisoned. I cannot speak concerning the moving pictures of Europe, but I can tell you that so far as the American workers are concerned the moving pictures are vile beyond the possibility of words to describe, and the whole industry is so completely controlled by big business that there is practically no chance of breaking in with a true idea.”36

Sinclair’s own experience with the picture business had been brief and unhappy (and worse was to come in the 1930s, when he financed Sergei Eisenstein’s Que Viva Mexico!). He was so disgusted that he had given up all idea of using the new medium to express his ideas:

“Again and again some smooth-spoken gentleman, wearing silk stockings and the latest tailored clothing, and perhaps a diamond ring on his finger, comes to me to propose to put my ideas into a moving picture. With time I discover that what he really means to do is to use my name as a means of selling stock, sometimes to a few friends of mine who happen to have money, and other times to the gullible public.

“Time and again I have had propositions to make one of my novels into a picture but always upon condition that I would ‘leave out the Socialism.’ And of course I have turned such propositions down.”37

One of these smooth-spoken gentlemen was Herbert Blaché, educated in England and France and the husband of Alice Guy Blaché. Like others of his kind, Blaché wanted to exploit the name of the author but little of his work. Sinclair needed the money and tried to disassociate himself from the film. Blaché sent him a telegram offering $500 cash: “Cannot very well agree to purchase story without your name and you must yourself realise the necessity to alter the story as it is impossible to produce a good picture with the story in present form and you would not want a bad picture.”38

Sinclair relented and the picture was released in 1917 as The Adventurer, “based on the famous novel by Upton Sinclair.” But Sinclair never wrote a novel of that name. The scenario, which had elements of a play within a play called The Pot-Boiler, was written by Harry Chandlee, who would, during the Red Scare, write a profoundly anti-socialist picture, and Lawrence McCloskey. The featured players were Marian Swayne and Pell Trenton. At least the film retained something of Sinclair in its exposure of graft and dishonesty in organized charities, but basically it was a melodramatic thriller.

Sinclair does not appear in Benjamin Hampton’s book of film history, nor does Hampton appear in Sinclair’s autobiography. With good reason, as Sinclair related: “A friend of mine undertook to make a moving picture version of my novel The Moneychangers [sic] and I helped in the making of a scenario, which faithfully followed the story. But after the scenario had been read, the producer [Hampton] told me that it was not suitable for a moving picture; it was, he said, ‘a grand opera.’ I was very much impressed by this pronouncement even though I did not understand it. The producer said that he would have to make another scenario for the picture, and he made one. And then I discovered the difference between a motion picture and a grand opera. In a grand opera the heroine dies in the last act. While in a moving picture she marries the hero amid a shower of spring blossoms, and lives happily ever after in the imagination of the feeble-minded audience.

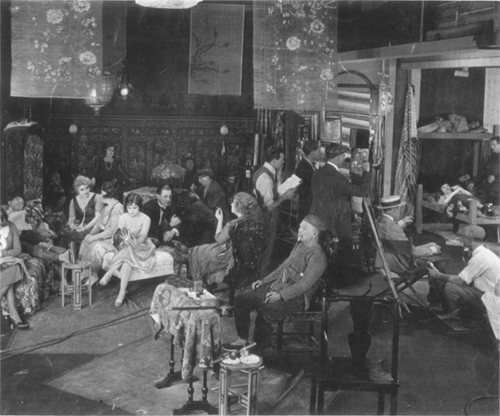

“So it happens that there is a picture entitled The Moneychangers by Upton Sinclair going the round of the United States, presumably a great many members of the working class go to see it, expecting to see something of mine, but as a matter of fact it has literally nothing to do with anything I ever wrote. My novel tells how Pierpont Morgan the elder caused the Wall Street run of 1907. The thing which is called The Moneychangers in the moving picture version is a blood-and-thunder melodrama of the drug traffic in Chinatown. And lest people should think that I am growing wealthy out of thus exploiting the incredulity of the workers, let me say that I was unable to stop the picture and as usual the financial organizations which are distributing the picture have made off with all the profits.”39

It should be pointed out that the “feeble-minded” viewers for which The Money Changers was altered was precisely that working-class audience Sinclair refers to in another context. It was not merely for the middle class that happy endings were invented. The film was a commercial success, in any case, grossing $100,000 by March 1921.40

In 1918, Sinclair was approached by two delegates of the Brotherhood of Railway Trainmen, who proposed a propaganda film to advocate continuing government control of the railroad system. Sinclair agreed to write a scenario and accepted the post of editor of the Motive Motion Picture Company (MMPC). The director-general of the company was David Horsley, who, with his brother William, had founded the first studio in Hollywood in 1911.41

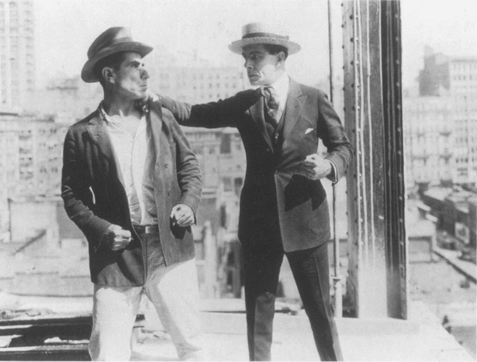

Filming Upton Sinclair’s The Money Changers, 1920. Jack Conway in the director’s chair, Harry Vallejo at the camera. Players relax while opium scene is shot.

Sinclair was paid an advance of $300 for his work, and he duly presented an outline for the scenario. Brave announcements were made, Samuel Gompers was conferred with and was “vitally interested.” But nothing was filmed.

“I realize now,” said Sinclair, “that I put myself in an unfortunate position by permitting them to sell stock upon the basis of my work, and I will never make that mistake again.”42

But Sinclair did not give up. In 1917, he tried to interest D. W. Griffith in The Daughter of the Confederacy, and in 1918, he wrote a synopsis for a comedy called The Hypnotist for Charlie Chaplin.43 Neither was made.

A CORNER IN WHEAT The socialists were only too anxious to use motion pictures to further their cause. Jack London’s The Valley of the Moon was filmed by the Bosworth Company in 1914; its story of a young couple freeing themselves from the suffocating grasp of a big city and escaping to the wilds of California carried a socialist message.

The Valley of the Moon, 1914, from Jack London’s novel. The battle in Oakland between strikebreakers and teamsters. The picture was used as Socialist propaganda. (Robert S. Birchard Collection)

“The strike scenes where a huge mob battled with the police, where the patrol wagons seemed to trample the rebellious workers, where men lay with broken heads and bleeding freely in the open, were, like the scenes which started the picture, true to the spirit in which Mr. London painted them—brutal, revolting and truthful,”44 reported the New York Dramatic Mirror.

But such presentations frequently encountered the opposition of the police. In Pittsburgh, they put an outright ban on the showing of socialist pictures on Sunday. “So they won’t allow you to show moving pictures, eh?” asked a socialist member of the Allentown (Pennsylvania) City Council of his packed audience. “If it were a booze joint, it probably would be given police protection.”45

Nothing encouraged socialism so much as the behavior of the robber barons, whose companies wielded the power of the multinational conglomerates of today. D. W. Griffith’s pioneering A Corner in Wheat (1909), taken not from Frank Norris, but, as Russell Merritt has discovered, from Channing Pollock’s 1904 play, The Pit,* was full of striking imagery and the kind of intercutting that would serve the cinema for decades. A scene inspired by Jean Millet’s painting The Sower opened the film, which dealt with a great wheat speculator whose intrigues would wreck the lives of these simple farm laborers. “No subject has been produced more timely than this powerful story of the wheat gambler, coming as it does when agitation is rife against that terrible practice of cornering commodities that are the necessities of life,” said The Biograph Bulletin.46

Contrasts from D. W. Griffith’s A Corner in Wheat, 1909. The Wheat King lauded for his acumen …

… the poor confronted by crippling prices. (Museum of Modern Art)

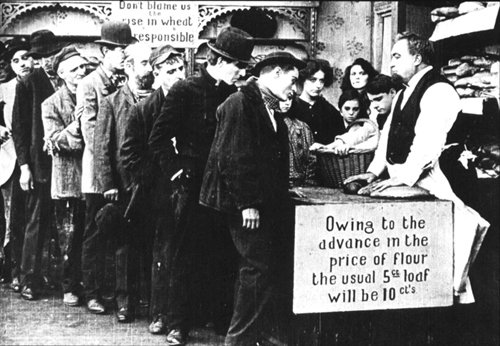

Griffith shows the excitement in the wheat pit at the stock exchange, “where we see them struggling like ravenous wolves to control the wealth they did nothing to create.”47 “The Gold of the Wheat” is represented by a lavish banquet where the Wheat King is lauded for his acumen, “The Chaff” by a bakery where the poor are confronted by crippling prices. A mother is forced to go without. The bread fund for the poor is reduced, and the police club the unlucky ones away from the bread line. At the moment of his triumph, when the Wheat King is told he has cornered the world supply, he trips and falls into one of his own bins of wheat, to be smothered, symbolically and literally, by his source of wealth. The film ends with a haunting shot of a figure broadcasting the seeds for next year’s crop—alone in a vast landscape.

One feels the film is not so much silent as gagged—having to convey points by waving arms, notices, and letters. The silence has yet to become eloquent. Nevertheless, a modern critic, Richard Schickel, calls it “a model of compression” and says, “Even now, one can scarcely speak too highly of the film.”48

The film was made again in 1914, when the cinema was growing more sophisticated and the story could fill five reels. The director was Maurice Tourneur, newly arrived from France, who, for a few prolific years, looked set to steal the crown from Griffith’s head. The Pit set a new mark for artistry and realism, with an almost full-size replica of the Chicago Board of Trade built by Ben Carré and filled with 500 extras.49

C. Gardner Sullivan, who so often wrote new versions of Griffith films, reworked A Corner in Wheat with The Corner (1915), about millionaire David Waltham’s attempt to corner the country’s food supply. We see the effect of his scheme on the family of a prosperous workingman who loses his position and then his savings when there is a run on the bank. His children are starving. He breaks a bakeshop window and steals four loaves, for which he is sent to the workhouse for thirty days. His wife, left destitute, is forced to sell her body to obtain food for her children.

Unusually for a film of this period, the husband is shocked, but does not blame her. He sets out to capture Waltham, ties him up in a warehouse surrounded by the food he has been stockpiling, and leaves him to starve to death. The picture ends with cases of food toppling over and smothering the millionaire.50

The New York Dramatic Mirror thought the film “startlingly well acted” by George Fawcett and Willard Mack, and Variety considered it among the best Ince productions. It was directed by Walter Edwards. Memories were short, and no reviewer connected it with the 1909 Biograph.

A remarkable socialist drama called Dust was made in 1916 for Flying A by writer Julian Lamothe and director Edward Sloman. A symbolic opening showed the laboring class coining their lives into money for their employer, a vision of the idealistic hero of the film, the young sociologist Frank Kenyon (Franklyn Ritchie). Dust was a clever title, referring not merely to the poor—“dust beneath the feet of the rich”—but to the deadly dust of the woolen mills which, so far as the workers were concerned, was as destructive as war itself.

The Corner, 1916. The impoverished wife (Clara Williams) “sells her body” to the rent collector (Charles Miller) in order to survive. Directed by Walter Edwards, written by C. Gardner Sullivan for Thomas H. Ince. (George Eastman House)

During the war, the concern and compassion of so many films of the Reform Era were replaced by hatred of the Hun. With the armistice, the Hun was transmuted into the Bolshevik.

In November 1918, the following letter was circulated to the heads of the film industry by David Niles, chief of the motion picture section of the U.S. Department of Labor:

“Gentlemen:

“The Motion Picture undoubtedly shortened the war by at least two months. This is the opinion of officers in the army who are in a position to know. The Motion Picture can do more to stabilize labor and help bring about normal conditions than any other agency. An injudicious use of Motion Pictures, on the other hand, can do our country incalculable harm.

“Constructive education will do infinitely more good than destructive propaganda. To portray the villain of a photo-play as a member of the I.W.W. or the Bolsheviki is positively harmful; while portraying the hero as a strong, virile American, a believer of American institutions and ideals, will do much good.”51

Directors and producers had to consult Niles before embarking on films about socialism or labor unrest, and he warned those who failed to cooperate of Federal censorship.52

Socialist projects, like Upton Sinclair’s for the railroad men and Frederick Collins’s for McClure’s Magazine on the achievements of American labor, collapsed. Antisocialist films proliferated in the postwar atmosphere of reaction. And whether Niles’s department approved or not, Bolsheviks were the all-purpose villains.

“There is much freedom of thought that should be imprisoned,” wrote the editor of Photo-Play Journal, “especially at this critical time in our national history. We should not lose sight of the fact that there are some writers with wildly socialistic ideas which should not be permitted the privilege of visualization.”53

That was written in 1919, the year of the Red Scare.

Charlie Chaplin entertained two prominent people at his studio in 1918. One was General Leonard Wood, former U.S. Army chief of staff, who had organized the Rough Riders with Theodore Roosevelt in the Spanish-American War. The other was Max Eastman, an American aristocrat who had become the country’s leading socialist writer. He had edited The Masses until its suppression; he supported Lenin and Trotsky and said so in his new paper, The Liberator.

In 1919, Chaplin was accused of financing Eastman’s paper and of being a parlor socialist. Chaplin agreed he was a friend of Eastman’s but denied backing his magazine: “I am absolutely cold on the Bolshevism theme; neither am I interested in Socialism. You know my war record. If The Liberator is seditious, it certainly should be suppressed.”54

At the same time, General Wood noted with approval a clergyman’s call for the deportation of Bolsheviks “in ships of stone with sails of lead, with the wrath of God for a breeze and with hell for their first port.”55

Such was the atmosphere during the year of the Red Scare, of which William E. Leuchtenburg has written, “Perhaps at no time in our history has there been such a wholesale violation of civil liberties.”56 Anarchists, aliens, Jews, socialists, pacifists, labor leaders, unionists, and even “hysterical women” were wrapped up together and popped into the same compartment of the popular mind: “Reds.”

Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer launched the Palmer Raids on November 7, 1919. In a number of cities, members of the Union of Russian Workers were arrested and treated brutally by the police. President Woodrow Wilson was ill and may not have known. The following month 249 aliens, virtually none of whom had committed an offense, were deported to Russia on the army transport Buford (the same ship Buster Keaton would use in The Navigator in 1924). Most of these people were anarchists, not Bolsheviks, and while some professed violence, like Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman, others were passionately nonviolent.57 The Commissioner of Ellis Island, Frederic C. Howe, resigned over the deportation issue.

The turn of the Bolsheviks came in January 1920 when, in a single night, more than 4,000 alleged Communists were arrested in thirty-three cities. In one town, prisoners were handcuffed, chained together, and marched through the streets. But by the end of 1920, as the threat of a Communist takeover of Europe receded, the Red Scare faded and the Wilson administration was replaced by the government of Warren G. Harding and a desire for “normalcy.”

As the Palmer Raids climaxed a long campaign against the left, so the Red Scare films were antisocialist tracts given new relevance by the word “Bolshevism.”

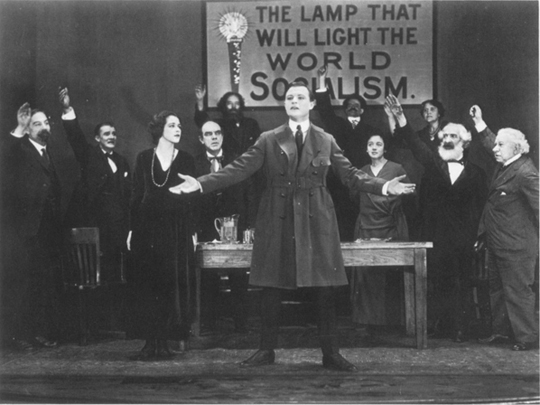

BOLSHEVISM ON TRIAL Bolshevism on Trial was adapted from the novel Comrades by the Reverend Thomas Dixon, a Southern populist who also wrote The Clansman, on which The Birth of a Nation was based. Published in 1909 as “A Story of Social Adventure in California,” Comrades was a satire on Upton Sinclair’s socialist experiment at Helicon Hall (sometimes referred to by those writing of the experiment as Halcyon Hall!) at Englewood, New Jersey, in 1906–1907. This colony had been a success, most obviously with children, but the press ridiculed it, deciding Sinclair had started it in order to provide himself with plenty of mistresses.58

The picture was originally entitled Shattered Dreams.59 The new title was adopted to boost it at the box office with the lure of the latest headlines. The film was an attack on socialism, intended to make it seem ludicrous in theory and impossible in practice.

Robert Frazer as Captain Norman Worth in Bolshevism on Trial, 1919, an attack on Socialism by the Rev. Thomas Dixon. (Museum of Modern Art)

The plot is a hotchpotch about a true-blue capitalist, Colonel Bradshaw (Howard Truesdell), whose inventions have “created work for thousands.” He is furious to discover that his son Norman (Robert Frazer) has fallen for a Red, a college girl named Barbara Alden (Pinna Nesbit). She takes Norman to the slums, where he is horrified by the squalor and begs her to leave such wretchedness to the charity workers.

“If you love me,” she says, “you should help me.”

Herman Wolff (Leslie Stowe) is a professional agitator; beetle-browed and villainous in every way, he sits at his desk surrounded by socialist pamphlets and a volume by Karl Marx.60

Posters on the exterior of a meeting hall make it evident that the scene was filmed in December 1918 and that the next event at the hall was to be a ball in aid of the Galician town of Przemysl, besieged by both Russian and German forces. Even more fascinating, the posters reveal that the heroine’s name was to have been Barbara Bozenta. One can only assume that by 1919 the foreign name would have lost her a degree of audience appeal.

Wolff uses the meeting to raise funds to purchase “the one spot on earth where they can all be free”—Paradise Island in Florida, with its vast hotel.61 Norman, carried away by the rhetoric, offers to buy the island. But the first few days in paradise prove purgatorial. No one volunteers for menial labor, and when the jobs are imposed the response is: “Unwilling labor is slavery!” A festive ball revives spirits and everyone is delightfully equal except the electricians in the basement. “Pretty soft for dem—dancin’ while we sweat for nothing a week,” says one. “Let’s give ’em a dose of darkness.” He pulls a switch and causes alarm on the dance floor. The lights are not restored by the electricians until Norman pays them out of his own pocket.

But then strikes spread like wildfire, Wolff deposes Norman and seizes power, and makes a speech not even the maddest socialist would dream of making: “Comrades, we can spread the Red Brotherhood over the world and come to power and riches.” Religion will be abolished, marriage laws banished—no wonder the white-garbed forces of righteousness race to the rescue. It can’t be the Ku Klux Klan this time, so it’s the U.S. Navy.

At this point appears the one memorable image of the film—a reversal of the scene in so many later Russian films when sailors tear down the Imperial banner and replace it with the red flag. An officer orders the red flag removed, and Colonel Bradshaw runs up the Stars and Stripes. The sailors cheer. It was an axiom of the industry that the one sure way of ensuring applause was to end on the United States flag, and this picture fades to its end title with the somewhat superfluous words “AMERICAN MOTION PICTURE.”

Just before the picture’s release, the trade press grew so excited it inadvertently caused a crisis. Moving Picture World felt the antisocialist propaganda was so strong it ought to have government support. It advocated exhibitors sending letters attacking socialism to the press—“then the battle is on.” It told its readers to exploit the fears of factory owners by linking socialism to Bolshevism—they would buy blocks of seats for their employees.

The U.S. Navy storms the Red enclave in Bolshevism on Trial, 1919. (Adam Reilly)

“Put up red flags and hire soldiers to tear them down … come out with a flaming handbill that the play is not an argument for anarchy.… Work out the limit on this and you’ll not only clean up, but profit by future business.”62

The protests flooded in, and Moving Picture World was forced to print a retraction. The producer, Isaac Wolper of the Mayflower Pictures corporation, and the distributor, Lewis J. Selznick of Select, were driven to deny that the film was propaganda and disowned their advertisements.

A year after this picture came out, its director, Harley Knoles, set up an independent production company in Los Angeles. He thought it would be equitable if he, his cameraman, the leading players, and the scenario writer all drew the same salary. He must have been staggered by the headline in Variety: “Communist Scheme Tried in Pictures.” The reporter described the idea as “Bolshevistic.”63

Not long afterward, hounded by creditors, Harley Knoles moved to England.

DANGEROUS HOURS Although prevailing opinion did not distinguish socialism from Bolshevism, it became a matter of box-office expediency to do so. When Thomas H. Ince announced a project called Americanism (versus Bolshevism) he quoted Samuel Gompers: “If I thought that Bolshevism was the right road to go, that it meant freedom, justice and the principles of humane society and living conditions, I would join the Bolsheviki. It is because I know that the whole scheme leads to nowhere, that it is destructive in its efforts and in its every activity, that it compels reaction and brings about a situation worse than the one it has undertaken to displace that I oppose and fight it.”64

Americanism was released in 1920 as Dangerous Hours. I wrote about this Fred Niblo film in The Parade’s Gone By …, but looking at it after a gap of twenty years, I was amazed by it once again. I knew it was an attack on socialism, but I never realized how vitriolic it was, nor did I remember artist Irvin Martin’s painted title backgrounds, which contained lurid symbols of death and destruction.

The film depends on the titles. The images are cut very fast, as if the editor65 could not wait to get to the meat of the scene—the text. It is another silent talkie. The performances are either wooden—Lloyd Hughes in particular—or absurd, and although the exterior sets of factory, shipyard, or Russian town are elaborate, they remain sets, and Niblo’s direction is too pedestrian to bring them all alive. The film is not badly made; it is simply prosaic. Had its visuals had the passion and hatred of its titles, Dangerous Hours might have been dangerous indeed.

The cinema was a populist medium. It favored the ordinary man, and it was surprisingly hard to make a right-wing film which denigrated him. Audiences responded with distaste to scenes of workers being beaten. Thus, the crowd had to be portrayed as a mob, snarling, waving cudgels, or tearing a town apart. There are just four policemen coping with the strikers in the opening scene of Dangerous Hours; in the attack on the shipyard town there are none at all.

But there was a strenuous effort to distinguish between the honest union man and the Bolshevik agitator. The strikers have “an honest grievance,” but we see another group, obviously based on the International Workers of the World, who are described as “the dangerous element, following in the wake of labor as the riff-raff and ghouls follow an army.” Among them is John King (Hughes)—“graduate of an American University—but … owing to his ardent sincerity, rich soil for the poisonous sophistry of fanatics, drones and dreamers”—and foreign-born Sophia Guerni (Claire Du Brey), the movement’s vamp, who feigns passion for him. He is attracted by her, “translating the feverishness of her shallow, thrill-craving soul as the Sacred Fires of the New Womanhood.”

The meeting of the revolutionaries in Sophie’s Greenwich Village studio is strikingly lit by George Barnes and given a smoky, conspiratorial atmosphere. The faces are carefully selected to send a shudder through the audience. There are even a couple of lesbians—“intellectuals abandoning their ‘mighty interests’ for the cause.”

Other major characters include Mary Weston (Barbara Castleton), “a sweet type of American womanhood,” who loves John and who just happens to have inherited her father’s shipyard, and Russian agent Boris Blotchi (Jack Richardson), “one of the bloodiest butchers of the Revolution.” (A blood-spattered cleaver decorates his titles).

At Mary’s shipyards, strikers refuse to have anything to do with the “four-flushing Bolsheviks,” and thus the film assuages the A.F.L. But the Bolsheviks try to seize control and at last King realizes their true purpose. “You are not interested in humanity—but murder!… We in America do not fight that way and what you say shall not be. This is America!”

Bolshevik conspirators from Dangerous Hours, 1920. (Museum of Modern Art)

The titles blossom in stars and stripes, but King is beaten up and abandoned, while the Bolsheviks carry “the Freedom of the World” to town. This played on the same fears as the German invasion pictures: a church is set on fire, a lavish home destroyed. King staggers into town, takes on Blotchi single-handed, and blows up the Bolsheviks with their own fiendish bombs. The picture ends happily with glimpses of contented workers in the shipyard and agitators, tarred and feathered, being carried out of town on a rail.

C. Gardner Sullivan brought to this Donn Byrne story the black and white politics of a Western.66 “Draw a strong line between laborers and agitators,” advised Moving Picture World, whose exploitation advice was considerably muted after its embarrassment over Bolshevism on Trial.67

The president of the Saginaw, Michigan, Manufacturers’ Association announced that he would buy 5,000 tickets for his employees to see Dangerous Hours: “I consider this production a most powerfully appealing picture for fairness, squareness and truthfulness and the very best method with which to combat the most dangerous evil that has confronted America since the subjugation of the diabolical Hun.”68

More than any other event of the Russian Revolution, the nationalization of women caught the imagination—or lack of it—of scenarists. Instead of what it was—a mobilization order to bring women into the labor force—American films passed it through the filter of melodrama and portrayed it as a license to rape. It lay behind one of the most lurid moments in Dangerous Hours: we see a soldier walking out of a cell, leaving a half-naked woman lying unconscious, and then a representation of Lenin addressing the Supreme Soviet, followed by columns of soldiers tramping past the body of a dead woman and her baby. Boots stamp on her outstretched arm.

“The nationalization of women was not invented by a motion picture producer,” said Gilbert Seldes. “It was published as a fact in all of our newspapers. The assassination of Lenin occurred seven times, until the poor man died of natural causes. For something like ten years, the most respectable and even then I suspect in many ways the best newspaper in this country—I’m speaking of the New York Times—did not have a true word out of Russia.”69

THE NEW MOON Soon after the Bolsheviks seized control of Russia, the American papers announced the abolition of the marriage law. The Soviet province of Saratov had decreed that it would be unlawful for a man to possess his wife alone but that she would become public property. This would ensure the propagation of a declining race.

“Such a story … had never been equaled in history,” wrote H. H. Van Loan, a former newspaperman who had become a successful scenarist. “It was a tremendous piece of news, and the most barbarous document ever conceived by the most brutal forces of man.”70 He claimed to have seen the original decree (actually a forgery).71 “It was horrifying. After reading its sixteen articles I wondered if I couldn’t, in at least a small way, prevent that decree from becoming active in the other provinces of Russia. At least, I could reveal to America and the rest of the civilized world the illiterate souls of a degenerate group of leaders.”72

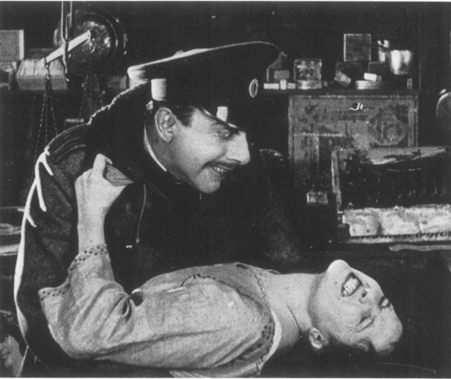

Russian frightfulness—and Orel Kosloff (Stuart Holmes) isn’t even a Bolshevik, although he is “in the pay of a foreign government.” New Moon, 1919, directed by Chet Withey, from an H. H. Van Loan story, with Norma Talmadge.

Van Loan wrote a story called “The New Moon” and sold it to Joseph Schenck for Norma Talmadge. It was directed by Chet Withey in 1919 in so exaggerated a fashion that even Variety was driven to call it “cheaply melodramatic.”73 Although it merely recalled the old anti-Russian pictures, with aristocrats escaping from revolutionaries instead of the other way around, it was taken more seriously than it deserved. “The newspapers have prepared people to expect any sort of outrages … so that nothing can well be presented, however brutal it may be, that is likely to be dismissed as an exaggeration,” wrote Wid Gunning.74

Julian Johnson of Photoplay was not hoodwinked, however. “Good morning,” he wrote. “Have you written your Bolshevist story yet? H. H. Van Loan has written his, and here it is. It is the sort of story you always find the literarily ambitious Dubuque young lady writing about New York; that is to say, she doesn’t know a blamed thing about New York except what she has read in the papers. And while I am wholly ignorant of Mr. Van Loan’s real and first-hand knowledge of Russia, his atmosphere and phraseology sound like studious cramming out of the Saturday Evening Post, the Literary Digest and the morning front pages, rather than resembling a personal reflection.”75

Van Loan was hurt to the quick by this review. He retorted that he had represented a chain of American newspapers abroad, had traveled the length and breadth of Russia, and would vouch for the accuracy of the detail in his story.76

The nationalization of women soon became a staple ingredient of movie hokum. Common Property came out at the end of 1919; Universal, having digested their H. H. Van Loan, set their story in that same “Saratov.”

“This decree may not be authentic,” admitted Picture Play, “but it carries a forceful idea for dramatic exposition.”77 The picture made inventive use of the American Expeditionary Force to Russia; troops arrive in the nick of time to rescue the women from a fate worse than death. “One can overlook their presence under the circumstances,” said Picture Play, “for it is easy to violate truth where the madmen of Russia are concerned.”78

THE BURNING QUESTION In October 1919, 17,000 Roman Catholic churches began showing films in their parish halls on a nonprofit basis.79 Films were produced especially for this network, to the distress of the exhibitors, whose trade suffered as a result.80 The Burning Question, one of the first releases, attacked foreign-born (i.e., Jewish) agitators.81 In case anyone was in any doubt, one title linked the three New Evils: “Socialism … Bolshevism … Anarchism …” After a skittish opening—an employee caught smoking his boss’s cigar—the humor evaporates and the film becomes Very Serious. The contractor is waging war on Reds. “Unless Bolshevism is checked,” he says, “its evil influence will crush the whole world.” Conviction is undermined by a subsequent title, “The Day the United States Declared War.” But this date was April 7, 1917, a full six months before the October Revolution; when the word “Bolshevik” was still virtually unknown in America. Russia was ruled by the Social Democrat Alexander Kerensky with the financial support of the United States.

The Burning Question, an anti-Bolshevik melodrama made in 1919 by the Catholic Art Association. (John E. Allen)

Having lost its sense of direction as well as its sense of humor, The Burning Question now loses its point in a lengthy subplot on the battlefields of France to show “the great work done by the Knights of Columbus.”82 “By the time the war is over, the Bolsheviks have to indulge in sabotage and rape to help us remember how they were trying to wreck the United States. By which time, we are too bored to care.

It was not long before the forces of anti-Semitism joined with those of anti-communism, although the first example came from an unexpected source, the playwright Augustus Thomas. He had been responsible for the film of Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle (see this page–this page), which was regarded as powerfully socialist. His The Volcano (1919), a distinctly antisocialist film, was made by the same team, directed by George Irving under Thomas’s supervision for producer Harry Raver. The original version was strongly anti-Semitic83 (the audience cheered it in some theatres),84 and it was only as a result of a campaign by a Yiddish newspaper that Raver was forced to make alterations.

The portrayal of Jews as Bolsheviks was a reflection of the popular belief. Allen Holubar made a picture for Universal called The Right to Happiness (1919), which opened, like the earlier anti-Russian pictures, with a pogrom that separates the two daughters of an American who happens to be living on the outskirts of the Jewish quarter of St. Petersburg. He retrieves one, but mourns the loss of the other, who is given a home by an outcast Jewish family and grows up a Red revolutionary. “Lenine and Trotzki send her to America to stir up trouble, and, of course, she stirs it up in her father’s factory without knowing who he is. In the end she is shot trying to protect her sister from the mob that has journeyed down to Long Island to attack her father’s house. The story ends in a haze of inconsistencies, with everyone weeping, and repenting and shouting nonsense about love.”85

Universal publicized it as “The Greatest Love Story Ever Told”86 and the public liked it. One theatre owner was so rapturous that his letter was used in the ads: “We had throngs of eager patrons lined in front of our box offices … exceeding our greatest expectations.”87

Arthur Guy Empey, the famous soldier who turned his book Over the Top into a film in 1918, came up with a sequel called The Undercurrent (1919) in which he played an American soldier returned from France and working in a steel mill. He falls prey to Red agents. Empey favored the deportation of radicals—“My motto for the Reds is SOS—Ship or shot”—and his picture was a diatribe. Julian Johnson thought it showed little knowledge of the subject beyond “a perusal of newspaper headlines.”88

The film was directed by Wilfred North, who had made The Battle Cry of Peace in 1915. Variety considered that Empey’s popularity had run its course (this proved accurate) and that the film, like his acting, was ragged and crude. But it admired the fact that it exploited “the evils of Bolshevism” and approved particularly of one episode in which a woman Red, “seeing that the law is about to checkmate her career, draws a revolver, kills her cringing associates, and fires the lead into herself. This bit is worthy of no less a Russian than Turgenev.”89

Bolshevik firebrand Sonia (Dorothy Phillips) leads the mob against the employer—who turns out to be her own father. The Right to Happiness, 1919. (National Film Archive)

But the audience at the Capitol Theatre, New York, far from being alarmed by it, laughed at this superpatriotic drama.

LAND OF OPPORTUNITY In the same year, 1919, a nationwide “Americanization” process began. Progressives hoped this would mean aid for immigrants. But in postwar America it meant a tough “Love us or leave us” policy. The melting pot had been replaced by the branding iron.

In December 1919, Franklin Lane, Secretary of the Interior, met with a group of producers and distributors to discuss the making of “Americanization” films “for the purpose of counteracting Bolshevism, radicalism and discontent against the U.S.”90 A committee was formed, which included Adolph Zukor, Lewis J. Selznick, and Lane as chairman. To prove how unlike the Bolsheviks they were, the producers took advantage of the situation to raise the price of the films. Exhibitors protested,91 but they were not supposed to make a profit any more than the producers were. The idea was circulation.

Lane said that he knew of no better weapon to stop the grave menace to civilization than the motion picture.92 He suggested that the industry organize immediately to spread the story of America as exemplified in the life of Abraham Lincoln. A round robin was sent to authors asking them to contribute screenplays for one- or two-reelers “not praising the government to the skies as perfect or Utopian”93 but pointing out in simple lessons the advantage of the republican system and the need for united and patriotic sentiment.

Selznick produced a two-reeler called Land of Opportunity especially for the committee. Ralph Ince, who directed the film, was featured as Lincoln and also played Merton Walpole, “an idler with an inherited fortune—busy with ‘pink’ theories for lack of a real share in the world’s work.” The story is set in a club, where this unlikely member assails his rich friends for buying their way into the courts and government and blinding the eyes of the poor by gifts to flashy charities. The others, who have no answer to this, accuse him of being a “Bolshevist,” and of belonging to the herd of uplifters who never lift anything but their voices. They walk out, leaving him with an elderly butler. “They don’t understand,” says Walpole, gazing at the pages of his book, Classes versus Masses by Yakem Zubko.

“Pardon me, sir,” says the butler, “but it is you who do not understand.” And he tells, in flashback, a story of how Abraham Lincoln, campaigning in a rural district and hearing of a boy on trial for murder in a nearby town, walked twenty miles to take charge of the defense and win the boy’s freedom.

“You tell the story as though you had been there,” says Walpole.

“I was the boy,” says the butler. “And the same America that gave Lincoln the opportunity to rise from a rail-splitter gave me justice in the courts—freedom —work—the opportunity to save—the field to serve.”

Left alone with his thoughts, Walpole tears out the pages of his subversive book and throws it on the fire. The film ends with the title “AMERICAN MOTION PICTURE.”

This curious anecdote, well produced though it was, hardly brought the socialist case crashing in ruins—it merely suggested the haphazard nature of American justice. The producers intended to release Land of Opportunity on Lincoln’s Birthday and to follow it with fifty-two more such films at weekly intervals.94 But the Red Scare was running out of steam, and in the end only a few more anti-Bolshevik films appeared.

STARVATION Hard as it is to believe, one film used the hungry masses of Europe to preach an anti-Bolshevik sermon. Behind it, thinly concealed, was Herbert Hoover, whose American Relief Administration was feeding the starving millions. And behind him was George Barr Baker, a lieutenant commander in the navy, who was based in Paris, where he worked as a publicist for the A.R.A. Historian Bert Patenaude, who has examined Baker’s papers in the Hoover Archives at Stanford University and who found documents quoted here, describes him as “a cultivated man, very sharp politically and with a good sense of humor.”95 Baker, like Hoover, was dedicated to the overthrow of Bolshevism, and he devoted months of his life, and thousands of dollars of his own money, to the documentary Starvation (1920).

The A.R.A. cause was aided by a number of newsreel cameramen, including George Zimmer, a navy photographer who shot most of Starvation, edited it, and received credit as director. Another was Donald Thompson,96 a maverick from Canada, who was paid by Leslie’s Weekly in New York. His footage and still pictures of child welfare work was “the best the A.R.A. has ever had.”97

Baker went into partnership with a shady distributor called Fred Warren. When he sent out invitations for the premiere, he was careful to distance himself from Warren: “We have not been able to control the announcements because the matter is now in the hands of the professional moving picture people and they use the methods of Barnum wherever possible. They have used Mr. Hoover’s name too freely in spite of all my efforts, nevertheless, every incident in this picture is absolutely authentic.… I do not believe that any woman in the working class who sees it will sit down at home with her children and calmly permit talk of direct action and other forms of radicalism.”98

Of course it was not the working class Baker had invited to the premiere, on January 9, 1920, at the Manhattan Opera House. He had invited the very rich—Otto Kahn—the very powerful—William Randolph Hearst—and the very influential—the editors of all the big newspapers.

The critical reaction was just what Baker needed. “Pictures of the worst cases of children—with protruding bones, swollen abdomens, and tight eyelids—brought sympathy and tears and relief at the thought that America was doing something to alleviate their sufferings.”99

“No fair minded person,” said Variety, “no matter what their leanings politically, could view this picture, particularly the scenes showing the frightful conditions in Russia, where the red banner of the Bolsheviki flies, and still have the slightest doubt as to whether or not a condition of government such as they have now is the best for the people.”100

(Herbert Hoover Archives, Stanford University)

Included in Starvation was footage of Bolsheviks being hanged and executed by firing squad. This all had a most unfortunate effect on audiences; Whites shot by Reds might have been more salutary. But here sympathy went to the victims. The scenes “left one cold with an unameliorated terror,” said the New York Times.101

Moving Picture World found a way of dealing with it, however: “At every point we have before us the contrast between the American way of dealing with a festering situation, and the unmerciful and less efficient way of the Central Powers. America erected a bulwark of food to stem the tide of the Bolsheviki, while the brutal methods of hanging and shooting … were resorted to as the only remedy by those of a lesser understanding.”102

“It is the first really powerful anti-Bolshevist and anti-Radical lesson offered in the United States,” Baker wrote to Alexander J. Hemphill of the Guaranty Trust Company, “which carries with it by indirection, instead of having all the earmarks of propaganda, the story of what happens to countries which abolish law and God and refuse to understand that without work there is no bread.”103 He gave the film its slogan: “The United States of America fights nations and men—but never women and children.”

It was not the ideal time for such a film. The price of food had soared in the United States thanks to the war, and by 1919 the cost of living was 79 percent higher than it had been in 1914.104 Food riots had scarred American cities only a couple of years earlier. Attendance at performances of Starvation was patchy, and the film was forced out of the Manhattan Opera House two weeks into its run.105

The film was hastily reedited. “The material very much shortened, and the shock very much reduced,” Baker wrote to Hoover. Having put $18,000 into the venture, he declared his confidence undiminished; he wanted to go ahead with it, “doing away with the professional crowd and reconstructing according to our ideas as generally carried out in the A.R.A. This plan does not involve you in any way.”

He had said he would not get Hoover into trouble, and “I have not done so. The enclosed clippings indicate that the public is not led to believe that you have any interest in the film.”106 Variety must have been among these clippings: “It was said to be propaganda for Hoover in his attempt to secure the presidential nomination, but there was so little of Hoover, it was propaganda of the subtlest kind.”107

Baker had a long talk over lunch with independent film distributor Fred Warren, then watched the film again. He drew up a list of cuts and alterations—a shot of Zimmer went from the opening—and suggested a new approach: “I would start off … by showing that even after the war much that was beautiful remained in the various countries of Central Europe; fine buildings and bridges undisturbed; that life was still worth living. Gradually I would drift into the question of Bolshevism as an after the war terror, and while doing this would show the blown bridges, White armies, and general scenes of the desolation which comes from revolution and unemployment. After all of this misery, which apparently began to spread widely with the initiation of Bolshevism, I would show the result; the bread lines and the starving children … As a climax to this, I would show the little naked girl, the little girls who are being stripped and weighed by the doctors and nurses, and who, if they are proved to be normal weight, will not be fed again until they begin to show fresh signs of the effects of starvation.”108

The film went round the country but never recovered from its initial failure, and Baker lost nearly $11,000.109 Hoover was not elected president until 1928, but Baker worked under Calvin Coolidge and was closely associated with Hoover during his presidency.

In 1923, Baker wrote to the Income Tax Bureau: “The film had various degrees of misadventure over a considerable period. It was always just about to be made to pay. However it never did reach that point and I paid the losses out of my own pocket, as indicated by my tax return. My advice to a young man about to risk money in motion pictures is—‘No.’ ”110

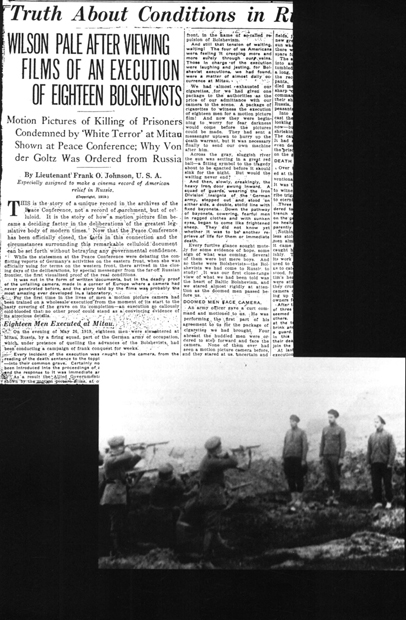

The fact that American cameramen were present to film these German troops executing Bolsheviks in Latvia in 1919 aroused angry comment in the German press. The Berlin Tagliche Rundschau called the filming “brutal,” while the execution itself was “quiet, dignified, and free from all offensive excitement.” A frame enlargement from a surviving fragment of Starvation. (Herbert Hoover Archives. Stanford University)

Perhaps the most effective anti-Bolshevik film did not deal with Bolshevism at all. It was D. W. Griffith’s epic of the French Revolution, Orphans of the Storm (1921). Griffith succeeded brilliantly in recreating the Terror at his new studio at Mamaroneck, on Long Island Sound, not far from the homes of some of the wealthiest people in the country.

Before portraying the bloodthirsty behavior of the mob, Griffith declares in a memorable title: “The French Revolution RIGHTLY overthrew a BAD government. But we in America should be careful lest we with a GOOD government mistake fanatics for leaders and exchange our decent law and order for anarchy and Bolshevism.”111

THE ETERNAL CITY The first version (1915) of Hall Caine’s The Eternal City was a film of socialist idealism. Caine lived in Rome when he wrote the novel, which was published in 1900, and told of the establishment of a socialist state and the appointment of a prime minister who put into effect the Christian socialism of Giuseppe Mazzini. The film was made on location in Rome, with the cooperation of the Italian government and the Vatican, and was exhibited throughout the world, “apparently without offence,” said Caine, “except perhaps in certain states of America.”112

Famous Players made the first version, and Sam Goldwyn decided to remake it in 1923. Caine assumed that he would film the story as he had written it, but he reckoned without Benito Mussolini. He was informed that the representatives of the Italian government in Washington objected to the subject and Mussolini himself had denied them all facilities in Rome for a film that would be based on the socialistic Eternal City.

Caine tried to withdraw from his contract, but the Goldwyn people told him they considered location scenes in Rome essential and that they had already spent a great deal of money preparing for them. They had been promised full civilian and military cooperation for a film which supported Fascist policy and argued that a free adaptation of the story was the only way out of the impasse.

“To this I objected,” wrote Caine, “that it would be false to the theory of my story to put Mussolini and Fascism into the places of Christian Socialism and the disciple of Mazzini; but the ultimate result of prolonged and sometimes painful legal negotiations was that I consented that an independent scenario should be written by another author, under her own name, and coupled with the name of my book. This has now been done, and the film shortly to be released will present a picture (no doubt vivid and faithful) not of the triumph of Socialism as dreamt of and desired by me, but of the triumph of Fascism as foreseen and desired and brought to pass by Signor Mussolini.”113

Like so many adults, Caine was bewildered by the whole experience. Why on earth would a film company buy a novel which had sold a million copies and render it unrecognizable to its devoted public? He could not understand, either, why Christian socialism, a worldwide movement, should be replaced by fascism, which was confined to Italy and of no appeal to any other country.

The official publicity was as mendacious as ever:

“It isn’t often that an author, and one of the most noted in the world at that, will agree to allow his story to be altered for the screen.… But such was the case with Sir Hall Caine’s immortal story of love and adventure.… Many producers had sought to purchase the film rights to the story before George Fitzmaurice made the successful offer. Not only was he able to induce the titled English novelist to agree to the changes, but the latter even assisted in working out the continuity, in conjunction with Ouida Bergere, Fitzmaurice’s wife.

Free extras for The Eternal City, 1923. Fascisti at the Coliseum, Rome. (Museum of Modern Art)

“The story was written years before the Fascisti of Italy had been thought of; but due to the modernization of the tale, and the persuasive tongue of Producer Fitzmaurice, Premier Mussolini, the chief of the Fascisti, appears in the picture.”114

Actually, Hall Caine had tried not merely to withdraw, but to stop the production while the company was on location in Rome, as he saw the film developing into Fascist propaganda.115

Goldwyn proceeded with the film, which turned into a very curious production indeed. David Rossi, an Italian orphan, has been cared for by a tramp (Richard Bennett) and is adopted by Dr. Rosselli, a pacifist, who rears him together with his daughter, Roma. They grow up (and become Bert Lytell and Barbara La Marr). David joins the army at the outbreak of war and Roma becomes a sculptor with the financial assistance of Baron Bonelli (Lionel Barrymore), the covert leader of the Communist party. David is reported killed.116

This is how the Daily Worker recounted the rest of the plot: “Despite the fact that this wealthy, world-wise Baron buys up her ‘masterpieces’ and pays her board bill, she returns pure and undefiled to her young lover who wasn’t killed after all.… The rich art patron, Baron Bonelli, is made into a war profiteering capitalist, who seeks to become Dictator of Italy by the road of the proletarian revolution. The wickedness of ‘red strikers’ is pictured by putting axes into the hands of a crowd of roughly dressed ‘extras’ and setting them to making kindling out of a railroad coach.… The brave youths return from the war, and find that their medals and banners are not properly respected. So they organize into mobs, and fling stilettos bearing anti-strike warnings at darkened doorways. When the reds organize to counter-attack, they are dispersed by the police, but the title-writer explains that Italy was fortunate in having a King with enough sense to turn the government over to Mussolini, the ‘man of the people.’ Mussolini and the King appear in person, of course.”117

The film’s cameraman, Arthur Miller, has recorded in his memoirs how scenarist Ouida Bergere had altered the story to include Mussolini and the Fascisti: “Mussolini was so impressed with the idea that his office was open to us at any time.” Blackshirts were provided to help with crowd control: “They did anything we asked of them. One Sunday we shot in five different locations in Rome, walking two thousand extras from one location to another and ending at the Coliseum.”118

As the advertisements said, “3,000 years ago they began building sets for The Eternal City.”119

Unhappily, Mussolini saw The Man From Home (1922), which Fitzmaurice had also made in Rome, and was apparently infuriated by its portrayal of Italian nobility. He demanded to see Fitzmaurice, who left for New York, and Miller sneaked out of Italy via Venice, with the last of the negative. “If the blackshirt boys had gotten their hands on the film that would have been the end of it.”120

THE VOLGA BOATMAN In 1926, the International Motion Picture Congress, held under the auspices of the League of Nations International Commission on Intellectual Co-operation, declared that while Russia should henceforth be treated in Western films in such a way that its “ancient culture” would be respected, the present government and conditions within the Soviet Union were to be ignored.121

But it is hard to ignore a regime with whom you are anxious to trade. The anti-Bolshevik films had died out by the early twenties, although some were still in circulation in Europe, representing the tip of an iceberg of propaganda freezing the waters between Russia and the United States. Lenin’s adoption of the New Economic Policy in 1921 suggested that capitalism was returning, albeit to a limited degree. And it altered America’s attitude. Russia had begun to look outward, and American tourists had begun visiting Moscow, prompting the Russian comedy Mr. West in the Land of the Bolsheviks, which used serial techniques to parody the American image of Soviet Russia.

The one gesture of goodwill, the one picture which portrayed the Bolsheviks in a relatively favorable light, was made by perhaps the most conservative figure in Hollywood, Cecil B. DeMille. That film was The Volga Boatman (1926).